Abstract

Background:

~100,000 US women receive emergency care after sexual assault each year, but no large-scale study has examined the incidence of posttraumatic sequelae, receipt of health care, and frequency of assault disclosure to providers. The current study evaluated health outcomes and service utilization among women in the six weeks after sexual assault.

Methods:

Women ≥18 years of age presenting for emergency care after sexual assault to twelve sites were approached. Among those willing to be contacted for the study (n=1,080), 706 were enrolled. Health outcomes, health care utilization, and assault disclosure were assessed via 6 week survey.

Results:

Three quarters (76%) of women had posttraumatic stress, depression, or anxiety, and 65% had pain. Less than two in five reported seeing health care provider; receipt of care was not related to substantive differences in symptoms and was less likely among Hispanic women and women with a high school education or less. Nearly 1 in 4 who saw a primary care provider did not disclose their assault, often due to shame, embarrassment, or fear of being judged.

Conclusions:

Most women receiving emergency care after sexual assault experience substantial posttraumatic sequelae, but health care in the six weeks after assault is uncommon, unrelated to substantive differences in need, and limited in socially disadvantaged groups. Lack of disclosure to primary care providers was common among women who did receive care.

Keywords: sexual assault, emergency care, health services utilization, posttraumatic stress

Approximately 100,000 US women seek emergency care after sexual assault annually (Smith et al., 2018). Adverse posttraumatic sequelae include pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection; women receiving emergency care after assault receive risk stratification and preventive interventions as needed to prevent these outcomes (Linden, 2011). Other adverse posttraumatic sequelae include neuropsychiatric symptoms such as posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance, alterations in cognition, mood, and arousal; Dworkin, Menon, Bystrynski, & Allen, 2017; Yehuda, 2002), depressive symptoms (Campbell, Dworkin, & Cabral, 2009; Zinzow et al., 2010), and pain/somatic symptoms (Kimerling & Calhoun, 1994; McLean et al., 2012; Stein et al., 2004). Such outcomes are common; indeed, PTS has a higher incidence after sexual assault than any other trauma (Yehuda, 2002).

Despite the ongoing epidemic of sexual assault, and the high morbidity of posttraumatic sequelae in survivors, to our knowledge no large-scale prospective studies have evaluated health care utilization in the early aftermath of assault. In this study, we assessed health services utilization during the first six weeks after sexual assault among adult women who presented for emergency sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) care. We examined the first six weeks after assault because for the majority of trauma survivors, symptom trajectories are established within 6–8 weeks after exposure (Hu et al., 2015; Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992), and women could meet criteria for PTS and related disorders by that time (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Based on previous small/single site studies (Ackerman, Sugar, Fine, & Eckert, 2006; Mengeling, Booth, Torner, & Sadler, 2015; Parekh & Brown, 2003; Sabina & Ho, 2014), we hypothesized that many sexual assault survivors with clinically significant symptoms would not receive care, and that receipt of care would be poorly matched to symptom or assault severity. In addition, we hypothesized that women from disadvantaged sociodemographic groups would have lower rates of utilization (Amstadter, McCauley, Ruggiero, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2008). Finally, based on previous literature (Agar, Read, & Bush, 2002; Sabina & Ho, 2014), we hypothesized that women sexual assault survivors would not always disclose their recent assault to care providers. In exploratory qualitative analyses, we examined themes reported by women regarding non-disclosure.

Method

Study Design

The current study is based on a large-scale observational study (Women’s Health Study) of women presenting to emergency care following sexual assault (Short et al., 2019). Adult women presenting for emergency care at one of the twelve participating sites in the Better Tomorrow Network (Albuquerque SANE Collaborative, UCHealth Memorial Hospital, Tulsa Forensic Nursing Services, Austin Safe, Denver Health, Crisis Center of Birmingham, Hennepin Healthcare, Christiana Care, University of Louisville SANE Hospital, Philadelphia SARC, Cone Health, Wayne State University Hospital and Wayne County SAFE, DC SANE) from 2015 to 2019 were recruited. Inclusion criteria included being at least 18 years of age and presenting for emergency care within 72 hours of sexual assault. Exclusion criteria included: inability to provide informed consent, pregnancy (due to varying trajectories of mood, pain, and sleep across pregnancy and the postpartum period; Bai, Raat, Jaddoe, Mautner, & Korfage, 2018; Li et al., 2019; Sedov, Cameron, Madigan, & Tomfohr-Madsen, 2018), planning on living with the assailant after the assault (due to likelihood of repeat traumatization and thus differing patterns of PTSS and other outcomes), fracture (as fracture is rare after SA and can influence pain outcomes, an important aim of the study), hospital admission, not speaking or reading English, no telephone access, no mailing address, unwilling to provide blood sample, incarceration, and inability in opinion of study staff to be able to follow the study protocol. Men were excluded because women comprise the majority of sexual assault survivors presenting for emergency care (Du Mont, Macdonald, White, & Turner, 2013), and gender differences in the development of sexual assault sequelae exist (Boisclair Demarble, Fortin, D’Antono, & Guay, 2017).

Protocol

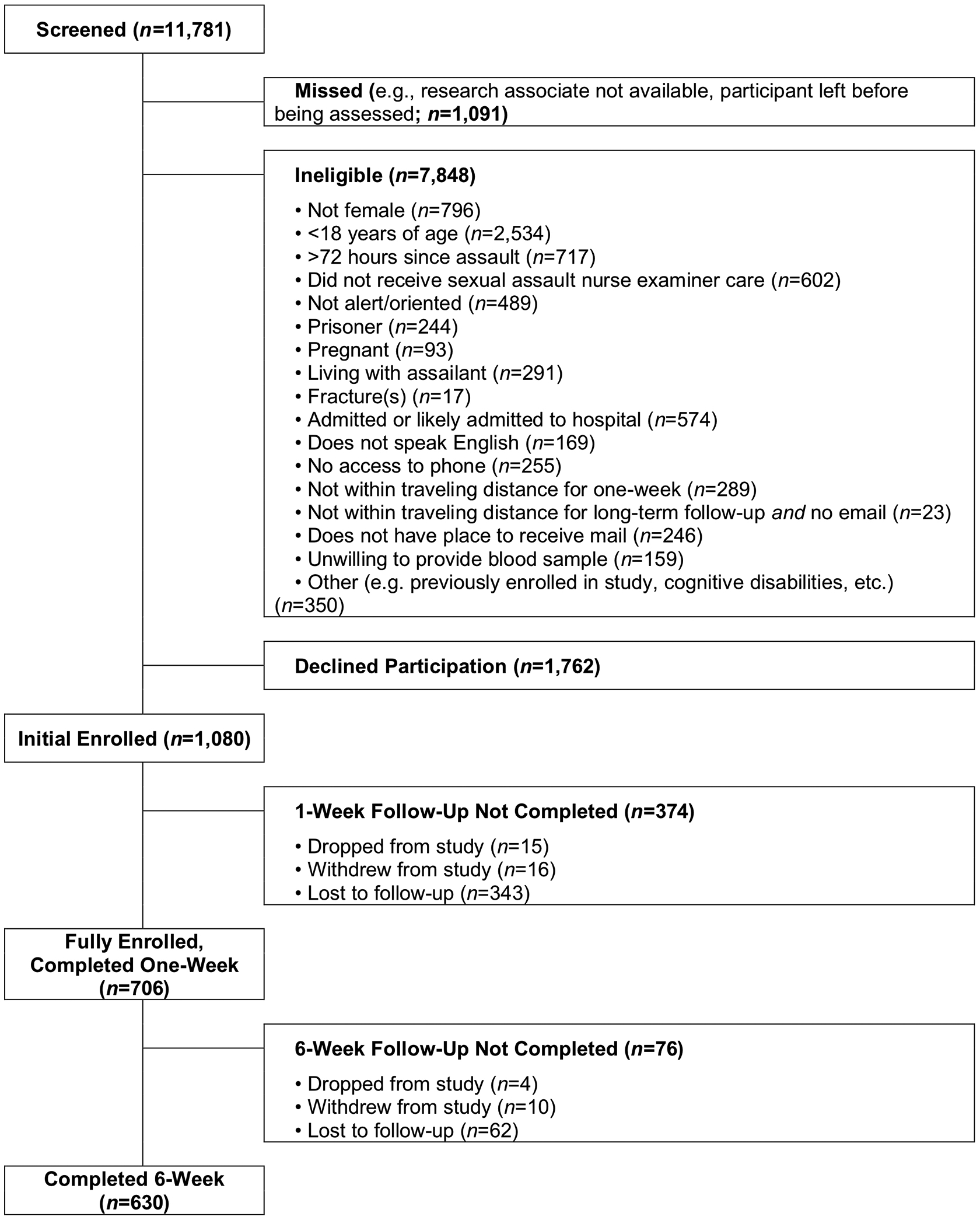

Individuals were approached at emergency care to determine eligibility and interest. Interested individuals provided written informed consent to share medical records and be contacted by phone in 24–48 hours to learn more about the study. Women contacted and willing to participate completed assessments and provided full written informed consent at one week, then completed assessments at one and six weeks (all one week assessments were completed in person via laptop, while six weeks could be completed in person or via internet or phone; Figure 1). Participants were compensated at each assessment. Data collection occurred from June, 2015 to May, 2020. Procedures were approved by University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Institutional Review Board, as well as local Institutional Review Boards for each site.

Figure 1.

Depiction of study flow.

Participants

Participants were women sexual assault survivors (n=706) aged 18 to 68 (M=28, SD=10; see Table 1). Most women identified as White (56%), followed by Black (15%), Other (15%), Native American (11%), and Asian (2%). Mutually exclusive racial categories were defined as follows: individuals who self-identified as Native Americans (with or without other categories) were categorized as Native American. Participants who self-identified as Black were categorized as Black, unless they also self-identified as Native American. Participants who identified as Asian, or Asian and “Other” or Pacific Islander, were counted as Asian. Participants who identified as White and no other category were identified as White. Participants who identified as White and any other group were categorized according to the other group. Participants who identified as Pacific Islander and “Other” were categorized as “Other.” All participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study.

Table 1.

Survivor demographic and pre-trauma clinical characteristics

| Baseline (n=706) n (%) or M (SD) |

Six Week (n=630) n (%) or M (SD) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28.4 (9.7) | 28.4 (9.7) | .973 |

| Race | .904 | ||

| White | 397 (57.3%) | 355 (57.2%) | |

| Black | 104 (15.0%) | 88 (14.2%) | |

| Asian | 13 (1.9%) | 10 (1.6%) | |

| Native American | 76 (11.0%) | 74 (11.9%) | |

| Other | 103 (14.9%) | 93 (15.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | .855 | ||

| Hispanic | 181 (26.3%) | 164 (26.6%) | |

| Education | .993 | ||

| Less than high school | 56 (8.0%) | 50 (8.0%) | |

| High school or equivalent | 172 (24.6%) | 149 (23.8%) | |

| Post-high school/some college | 330 (47.1%) | 298 (47.6%) | |

| 4-year degree | 113 (16.1%) | 103 (16.5%) | |

| Graduate degree | 29 (4.1%) | 26 (4.2%) | |

| Annual Income | .994 | ||

| <$20,000 | 254 (38.9%) | 225 (38.6%) | |

| $20,000–39,999 | 156 (23.9%) | 140 (24.0%) | |

| $40,000–79,999 | 159 (24.4%) | 145 (24.9%) | |

| $80,000+ | 83 (12.7%) | 73 (12.5%) | |

| Work Status | .965 | ||

| Student | 152 (22.0%) | 137 (22.2%) | |

| Not currently working | 192 (27.7%) | 169 (27.3%) | |

| Part-time | 84 (12.1%) | 79 (12.7%) | |

| Full-time | 264 (38.2%) | 235 (37.8%) | |

| Pre-trauma anxietya | 189 (26.8%) | 168 (26.6%) | .500 |

| Pre-trauma depressiona | 160 (22.7%) | 142 (22.5%) | .671 |

PROMIS anxiety 8a score t-score ≥61, or PROMIS depression 8b t-score ≥61 (Cella et al., 2010; National Center for PTSD, 2019).

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic data was collected at one week, including for age, race, ethnicity, work status, educational attainment, and income.

Assault Characteristics.

Assault characteristics were obtained from the sexual assault medical/forensic records. These were coded by trained research assistants and staff, under supervision of the last author. Training included review the coding protocol and practice coding of four records, which were then reviewed to assess reliability. Coding was regularly assessed for accuracy, and each record was double coded by separate research assistants, with disagreements adjudicated by the senior author.

Each variable was coded as follows: “completely conscious” was coded 1 if participants denied any loss of conscious. Otherwise, participants were coded 0 if the participant was either fully unconscious (e.g., passed out, asleep) or had periods of loss of consciousness (e.g., due to intoxication, head injury, strangulation). Types of assault were coded as penile-vaginal penetration, digital penetration, penetration with a foreign object, penile-anal penetration, penile-oral penetration, vaginal-oral penetration, or the participant being made to perform oral or manual intercourse on the assailant. Relationship to assailant was coded by examining whether participants indicated a relationship to the assailant in the medical/forensic record (e.g., stranger, spouse, non-spousal relative, friend, acquaintance). Number of assailants was coded by the number of assailants discussed in the assault narrative. Strangulation was coded if any type of strangulation was discussed in the medical/forensic record.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; Cella et al., 2010)

PROMIS forms 8a and 8b were used to measure self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms at six weeks, respectively. At one week, pre-trauma anxiety and depression were assessed by asking participants to rate items based on the week prior to the assault. Each PROMIS form contains eight items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1=Never through 5=Always). The PROMIS forms have demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, including internal consistency, construct validity, and discrimination of clinically significant symptoms (Cella et al., 2010). A t-score of >60 was used to classify those with significant symptoms (Cella et al., 2010).

PTSD Checklist – 5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013)

The PCL-5, a 20-item self-report measure of PTS, was administered at six weeks. Participants rated current DSM-5 PTS symptoms (e.g., Repeated, disturbing dreams of the stressful experience) on a 4-point Likert scale (0=Not at all; 4=extremely). Instructions were modified to ask participants to rate symptoms related to their recent sexual assault. The PCL-5 has excellent psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity (Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015). A score of >33 was used to identify clinically significant PTS symptoms (National Center for PTSD, 2019).

Pain Severity Numeric Rating Scale (NRS; Bijur, Latimer, & Gallagher, 2003)

Pain severity (0–10 NRS score) at six weeks was assessed in each body region using an adapted version of the Regional Pain Scale (RPS; Wolfe, 2003). Pain was described as “physical pain” including “pain/tenderness” and “pain or aching” to exclude “emotional pain.” Pain severity in each body region during the week prior to assault was assessed at one week evaluation using the same methodology. Change in pain score of ≥2 in one or more body regions was defined as clinically significant new or worsening pain (Bijur et al., 2003).

Follow-up Procedures and Health Care Utilization.

Information regarding standard care protocols, including follow-up procedures, was obtained from SANE leadership at each site. Health care utilization was assessed via six week follow-up survey. Participants were asked whether they had received care from categories of providers and given examples of providers within that category. For example, for primary care, they were asked “Since the assault, have you received care from a primary care provider (for example, family practitioner, internal medicine doctor, general doctor, or nurse practitioner”)?” For mental health care providers, they were asked, “Since the assault, have you received care from a mental health provider/counselor”, and given the options of “psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, crisis counselor, substance abuse counselor, other”. Crisis counselors included providers of either short- or long-term counseling, either in-person or via 24/7 crisis phone lines. If participants responded yes, they were then asked if they had told the provider about the assault. If the participant reported that they had not informed the provider, they were asked the open-ended question, “Why not?” Open-ended items were categorized into specific themes.

Data Analysis

Sample size was determined by power analysis to achieve power of .80 for the overall study hypotheses (Short et al., 2019). Descriptive analyses were used to assess participant and assault characteristics, adverse health outcomes at week six, the prevalence of receiving health care services, and disclosure of sexual assault to providers (Table 2), and demographic and clinical characteristics (Tables 2 and 3). Student’s t-tests (two-tailed) were used to compare symptoms among those who did and did not receive health care (Supplementary Table 1). Chi square analyses were used in stratified analyses to determine whether assault characteristics were associated with differential healthcare utilization. Relative risk of not receiving different types of care for historically disadvantaged groups (i.e., Black vs. White, Native American vs. White, Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic, high school education or less, and Income of <$20,000) was calculated. Analyses were performed using SPSS Version 25 and R (IBM Corp, 2017; Team, 2013). Missing data were handled by testing whether there were any significant demographic or clinical differences between participants who completed follow-ups vs those who did not; any differences were to be statistically controlled. Participants were dropped listwise if they had missing data on the relevant analyses. Otherwise, all participants were included in analyses (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Types of health care providers seen during the first six weeks after sexual assault, according to provider type, and sexual assault disclosure rate and proportion who felt supported if disclosed

| Received Services During First Six Weeks After Assault N (%)a | Received Services but Did Not Disclose Assault N (%) | Disclosed and Felt Supported N (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider Type | All (n=630) | Mental health sequelaeb (n=475) | New/worse painc (n=409) | All | Mental health sequelaeb | New/worse painc | All |

| Mental health provider | 239 (38%) | 191 (40%) | 163 (40%) | 6 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (3%) | 212 (93%) |

| Psychiatrist/Psychologist | 145 (23%) | 114 (24%) | 101 (25%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 130 (93%) |

| Social worker | 40 (6%) | 30 (6%) | 31 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 35 (90%) |

| Crisis counselor | 100 (16%) | 79 (17%) | 65 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 93 (95%) |

| Primary care provider | 230 (37%) | 182 (38%) | 166 (41%) | 56 (24%) | 44 (24%) | 38 (23%) | 159 (93%) |

| OB/Gyn | 88 (14%) | 72 (15%) | 63 (15%) | 9 (10%) | 7 (10%) | 4 (6%) | 73 (94%) |

| Alternative medicine provider | 24 (4%) | 18 (4%) | 17 (4%) | 8 (33%) | 6 (33%) | 6 (35%) | 15 (100%) |

| Physical therapist or chiropractor | 34 (5%) | 27 (6%) | 31 (8%) | 21 (62%) | 16 (59%) | 18 (58%) | 12 (100%) |

| Infectious disease or health department | 56 (9%) | 42 (9%) | 37 (9%) | 7 (13%) | 7 (17%) | 5 (14%) |

47 (96%) |

Abbreviations: OB/Gyn=Obstetrician/Gynecologist.

A single sexual assault survivor could see multiple types of providers (see text).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 score > 33, PROMIS anxiety 8a score t-score ≥61, or PROMIS depression 8b t-score ≥61 (Cella et al., 2010; National Center for PTSD, 2019).

Increase of ≥2 in 0–10 numeric rating scale pain score between week prior to assault (assessed at one week follow-up) and 6 weeks (Bijur et al., 2003).

Table 3.

Types of health care providers seen during the first six weeks after sexual assault (SA), non-disclosure rate according to provider type, and proportion who felt supported if did disclose by specific mental health symptoms

| Received Services During First Six Weeks After Assault N (%)a | Received Services but Did Not Disclose Assault N (%) | Disclosed and Felt Supported N (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider Type | All(n=630) | Significant PTSb (n=390) | Significant depressionc (n=345) | Significant anxietyc (n=407) | All | Significant PTSb | Significant depressionc | Significant anxietyc | All |

| Mental health provider | 239 (38%) | 162 (42%) | 138 (40%) | 167 (41%) | 6 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 212 (93%) |

| Psychiatrist or Psychologist | 145 (23%) | 99 (25%) | 88 (26%) | 101 (25%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 130 (93%) |

| Social worker | 40 (6%) | 22 (6%) | 22 (6%) | 29 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 35 (90%) |

| Crisis counselor | 100 (16%) | 66 (17%) | 56 (16%) | 72 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 93 (95%) |

| Primary care provider | 230 (37%) | 153 (39%) | 135 (39%) | 158 (39%) | 56 (24%) | 35 (23%) | 34 (25%) | 39 (25%) | 159 (93%) |

| OB/Gyn | 88 (14%) | 61 (16%) | 55 (16%) | 59 (15%) | 9 (10%) | 6 (10%) | 5 (9%) | 5 (9%) | 73 (94%) |

| Alternative medicine provider | 24 (4%) | 14 (4%) | 16 (5%) | 17 (4%) | 8 (33%) | 4 (29%) | 5 (31%) | 6 (35%) | 15 (100%) |

| Physical therapist or chiropractor | 34 (5%) | 25 (6%) | 22 (6%) | 24 (6%) | 21 (62%) | 16 (64%) | 12 (55%) | 14 (58%) | 12 (100%) |

| Infectious disease or health department | 56 (9%) | 38 (10%) | 33 (10%) | 38 (9%) | 7 (13%) | 7 (18%) | 7 (21%) | 7 (18%) | 47 (96%) |

Abbreviations: PTS=posttraumatic stress; OB/Gyn=Obstetrician/Gynecologist.

A single sexual assault survivor could see multiple types of providers (see text).

“Significant” PTS is defined >33 on the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist.

“Significant” depression or anxiety is defined as moderate or severe (≥61 on the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS]).

Qualitative variables were analyzed using thematic analysis, the systematic examination of text by identifying and grouping themes and coding, and classifying and developing categories (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Pope & Mays, 1995). Coders reviewed all qualitative responses and noted initial categories of themes that emerged. Themes were then developed inductively as coders reviewed the responses, allowing a data-informed analytic approach. Identified themes and corresponding responses were discussed by the coding team, supervised by the last author. Any discrepant codes were discussed in this team approach until consensus was reached.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Adult women sexual assault survivors were screened for eligibility at the time of emergency care. Among eligible survivors who were approached (2,842), 1,080 provided initial consent at the time of emergency care, and 706 were enrolled into the full study (Figure 1). Most enrolled sexual assault survivors were white and less than 30 years of age with some education past high school (Table 1). Median annual participant income was $20,000-$39,000. Participants were recruited from Albuquerque SANE (197/706 (28%)), UCHealth Memorial Hospital (132/706 (19%)), Tulsa SANE (112/706 (16%)), Austin SAFE (63/706 (9%)), Denver Health (57/706 (8%)), Crisis Center of Birmingham (43/706 (6%)), Hennepin SARS (29 (4%)), Christiana Care (26 (4%)), Louisville Health (15/706 (2%)), Philadelphia SARC (14/706 (2%)), Moses Cone Health (10/706 (1%)), Wayne County SAFE (6/706 (1%)), and DC SANE (2/706 (1%)). There were significant site differences in demographics (differing distributions of Black, White, Other, and Latina women by site), but not any post-assault clinical characteristics assessed by one-way ANOVA (ps>.076) or any form of health care seeking (ps>.080), with the exception of receiving care from an Ob/Gyn (which post-hoc contrast testing revealed was more commonly reported by participants from Wayne County SAFE, Crisis Center of Birmingham, Philadelphia SARC, and Austin SAFE than several other sites).

Six week follow-up assessments were completed in 630/706 (89%); no significant differences in demographic, assault, or clinical characteristics were observed between sexual assault survivors who did and did not complete six week follow-up (Table 1). Thus, no covariates were retained in further analyses.

Assault Characteristics

Over half of women reported loss of consciousness at some point during the assault due to head injury, strangulation, alcohol or substances, or any other reason (419/705 (59%)). A majority 417/484 (86%)) reported penile-vaginal penetration, while others reported anal (74/484 (11%)), digital (253/484 (36%)), or oral (167/484 (24%)) penetration. Assailant’s relationships to the survivor were: friend or acquaintance (322/700, (46%)), stranger (161/484 (23%)), former romantic partner (41/700 (6%)) planned first encounter (e.g., first date; 41/700 (6%)), current romantic partner (35/700 (5%)), non-spousal family member (7/700 (1%)), or missing/unknown (102/700 (14%), while 17/285 (6%) reported sexual assault by multiple individuals. A minority (72/397 (18%)) reported the presence of a weapon during the assault while 77/241 (32%) experienced strangulation during assault. A total of 537/706 (76%) had record of some form of physical injury during the SANE exam.

Routine follow-up procedures at emergency care sites

All sexual assault survivor emergency care sites (12/12, 100%) provide follow-up information regarding medical, legal, and/or counseling resources (e.g., via business cards, handouts, social workers, case managers, local advocacy groups). Half of sites (6/12, 50%) performed telephone or email follow up, and a third (4/12, 33%) attempted to schedule follow-up visits on all survivors. Other emergency care sites (3/12, 25%) performed follow-up on survivors who tested positive for sexually transmitted infection or needed medical or forensic care.

Adverse health outcomes at six week

The majority of sexual assault survivors experienced clinically significant adverse neuropsychiatric sequelae. Clinically significant PTS symptoms were present in 390/613 (64%) women sexual assault survivors six weeks after assault, 345/625 (55%) had clinically significant depressive symptoms, and 407/626 (65%) women had clinically significant anxiety symptoms. One or more of these outcomes was experienced by 475/627 (76%) women at six weeks. Clinically significant new or worsening pain was reported by 409/627 (65%) of women, and 557/629 (89%) women had clinically significant new or worsening somatic symptoms (most commonly difficulty concentrating and taking longer to think).

Receipt of mental health specialty care in the first six weeks after sexual assault

Less than two in five sexual assault survivors received any mental health care services during the first six weeks after sexual assault (Table 2). Approximately one in four women were seen by a psychiatrist or psychologist. Less than one in five were seen by a crisis counselor. Receipt of services from more than one kind of mental health provider was rare: 29/630 (5%) saw a crisis counselor and a psychiatrist, 26/630 (4%) saw a crisis counselor and a psychologist, and 18/630 (3%) saw a social worker and a psychiatrist.

Receipt of mental health specialty care among those with neuropsychiatric sequelae

Rates of mental health care were similar among women assault survivors with substantial mental health sequelae (PTS, depression, and anxiety, Table 2). Less than 1 in 4 of such women were seen by a psychiatrist or psychologist, <1 in 5 were seen by a crisis counselor, and ~1 in 20 were seen by a social worker. There were some statistical differences, but no clinically relevant differences (Bijur et al., 2003; Cella et al., 2010; National Center for PTSD, 2019), in the severity of PTS, depressive, anxiety, and pain symptoms one week and six weeks after assault among women who did and did not receive mental health services (Supplementary Table 1).

Receipt of other medical care

Approximately 2 in 5 women sexual assault survivors with mental health sequelae saw a primary care doctor within the first six weeks after assault; approximately 1 in 6 saw an OB/GYN (Table 2). Rates of receipt of care from primary care and OB/GYN providers were similar among women with and without mental health sequelae (Table 2), and among women with and without specific adverse mental health outcomes (PTS, depression, and anxiety, Table 3) and among women with new or worse pain (Table 2). Sexual assault survivors who received care from a PCP or OB/GYN during the first six weeks after assault were also more likely to receive care from a mental health specialist (136/261 [52%] vs. 101/356 [28%], χ2=34.9, p<.0001). Receipt of care from an alternative medicine provider or physical therapist/chiropractor was uncommon (Table 2).

Receipt of care in the early aftermath of sexual assault among women from historically disadvantaged sociodemographic groups

Hispanic sexual assault survivors were less likely to receive any health care services or mental health care services (Table 4). Women with a high school education or less were less likely to receive mental health care. No differences in receipt of health care were observed in African Americans or Native Americans women vs. other women.

Table 4.

Relative risk of not receiving health care services during the first six weeks after sexual assault among historically disadvantaged socioeconomic groups (n=706)

| Any Health Carea RR (CI) | Mental Health Care RR (CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Black vs. white | .90 (.56 to 1.24) | 1.02 (.82 to 1.22) |

| Native American vs. white | 1.10 (.76 to 1.45) | 1.10 (.89 to 1.31) |

| Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic | 1.38 (1.16 to 1.61) | 1.25 (1.11 to 1.38) |

| High school or less vs more | 1.13 (.91 to 1.36) | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.33) |

| <20K vs more | 1.16 (.93 to 1.39) | 1.13 (.99 to 1.26) |

Abbreviations. RR=Relative risk; CI=Confidence Interval.

Any health services defined as mental health care provider, primary care provider, alternative medicine, chiropractor/physical therapist, infectious disease specialist or obstetrician/gynecologist.

Receipt of care in the early aftermath of sexual assault by assault characteristics and demographic factors

There were no significant differences in receipt of health care between those who did and did not report loss of consciousness during the assault (χ2=.03, p=.856), type of penetration reported (ps>.065), relationship with assailant (ps>.088), whether or not a weapon was present (χ2=.67, p=.413), or whether strangulation occurred (χ2=1.76, p=.185).

Stratified analyses indicated that among Latina survivors, health care receipt was increased if they endorsed digital penetration by the assailant (vs. not reporting this type of penetration; χ2=4.90, p=.027), or being forced to perform manual intercourse on the assailant (vs. those who were not forced to perform manual intercourse; χ2=8.07, p=.005). No other differences were noted (ps>.161). Among Black women, anal penetration (vs. not reporting anal penetration) was associated with higher likelihood of receiving health care (χ2=4.17, p=.041), while being forced to engage in manual intercourse on the assailant was associated with lower likelihood of receiving health care (vs. not being forced to perform manual intercourse, χ2=4.80, p=.028). No other significant associations were noted (ps>.181). For American Indian/Alaskan Native women, those who endorsed forced engagement in oral sex on the assailant were more likely to receive health care (vs. those who were not forced to perform oral sex; χ2=4.48, p=.034), but no other associations were significant (ps>.228). For women with a high school education or less, there was a trend toward differences in health care receipt by relationship with assailant (F (4, 165)=2.34, p=.057), which posthoc contrasts revealed were due to greater health care received for those assaulted by current vs. former romantic partner (p=.022), planned first encounter vs. former romantic partner (p=.003), and friend or acquaintance vs. former romantic partner (p=.012). Strangulation was also associated with higher receipt of health care (χ2=7.23, p=.007) in this group, while no other characteristics were predictive of health care receipt (ps>.131).

Disclosure of sexual assault to care providers

Ten percent of women who saw an OB/GYN and approximately one quarter of women who saw a primary care provider did not report their sexual assault (Table 2). In contrast, the vast majority disclosed their assault to mental health specialists. Rates of non-disclosure to both primary care providers and OB/GYN providers were similar among women with and without mental health sequelae (Tables 2 and 3). Rates of non-disclosure to primary care and to OB/GYN providers were higher among women who did not see a mental health care provider (OB/GYN: 7/39 (18%) vs. 9/88 (10%), χ2=1.57, p=.21, Primary Care: 39/113 (35%) vs. 56/230 (24%), χ2=4.57, p=.03), indicating that non-disclosure was not due to concurrent disclosure to a mental health provider.

Qualitative findings for non-disclosure of sexual assault to health care providers

Among women who did not disclose their recent sexual assault to care providers (n=292), 108 (27%) provided qualitative comments. Not feeling comfortable disclosing (38/108, 35%) was the most common theme. Example comments within this theme included: “it’s a heavy subject and I don’t…know how to bring it up,” “[Provider] will judge me,” “I just want to…forget it,” “I felt ashamed,” “Scared and embarrassed,” “Not [provider’s] business,” and “I just don’t want to.” The assault being irrelevant to the appointment (34/108, 31%) was another common theme; representative comments included: “It is no benefit for them to know,” “Didn’t pertain to my appointment,” “Extremely irrelevant,” “It wasn’t related,” and “No need.” Other reasons for non-disclosure included: “Was focused too much on treating alcoholism,” “Forgot,” “Don’t care,” “Nothing is wrong,” “My provider is different every time,” and “Was just trying to get by”.

Discussion

In this first large-scale prospective study of adult women sexual assault survivors, recruited from twelve sexual assault emergency care sites, assault resulted in a high burden of mental and physical suffering. More than three quarters continued to experience clinically significant PTS, anxiety, or depressive symptoms six weeks after assault, and the majority had clinically significant new or worsening pain. Despite this, less than two in five received mental health care during the weeks after assault. Receipt of physical health care was also uncommon; less than two in five women saw a primary care provider, and only about one in six saw an OB/GYN. Care was poorly stratified: no clinically relevant differences in mental or physical health sequelae were present in women who did and did not receive care. Hispanic women were less likely to receive any care, and women with a high school education or less were less likely to receive mental health care. Nearly all women who received care from a mental health provider disclosed their assault, but non-disclosure to medical providers was common. Nearly one in four women did not disclose their recent assault to their primary care provider. The most common reason for non-disclosure was not feeling comfortable due to shame, embarrassment, or fear of being judged.

The high burden of posttraumatic mental and physical health sequelae for sexual assault survivors is consistent with prior smaller-scale studies (Kimerling & Calhoun, 1994; Price, Davidson, Ruggiero, Acierno, & Resnick, 2014; Young-Wolff, Sarovar, Klebaner, Chi, & McCaw, 2018). Findings that receipt of follow-up care is uncommon are consistent with prior single site, administrative, and nationally representative samples (Ackerman et al., 2006; Amstadter et al., 2008; Price et al., 2014; Young-Wolff et al., 2018). Current results expand upon this work using a prospective, multi-site cohort of women sexual assault survivors receiving emergency care in a variety of settings (e.g., hospital, community-based). These results provide further evidence that mental and physical health sequelae of assault are pervasive, and that receipt of care in the weeks after assault is uncommon and more stratified by socioeconomic advantage than symptom severity. This is consistent with prior research indicating that elevated psychological symptoms may not translate to seeking health services among sexual assault survivors (Darnell et al., 2015; Kimerling & Calhoun, 1994; Price et al., 2014). The fact that, consistent with prior work (Alvidrez, Shumway, Morazes, & Boccellari, 2011; Price et al., 2014; Wyatt, 1992), socioeconomic advantage is a bigger driver of care than symptoms (though mixed findings have been reported; Darnell et al., 2015; Millar, Stermac, & Addison, 2002), is unfortunate given that socioeconomic disadvantage increases risk for sexually assault (Morgan & Truman, 2018). Future research would benefit from continuing to examine what variables related to socioeconomic disadvantage are most critical in interfering with receipt of care, as at least one study identified that having insurance, including Medicaid, outperformed race and ethnicity as a predictor of receiving health services after assault (Price et al., 2014). This could help to identify how to facilitate appropriate health services for women who have clinically significant symptoms after assault.

In contrast with prior research indicating assault related factors predicted the receipt of health care (Ackerman et al., 2006; Millar et al., 2002) and formal help seeking broadly (Larsen, Hilden, & Lidegaard, 2015), the current findings did not identify assault-related predictors of health care utilization in the overall sample. However, stratified analyses indicated that type of penetration was differentially associated with health care utilization among Black, Latina, and American Indian/Alaskan Native women. Further, consistent with prior research in sexual assault survivors (Ackerman et al., 2006; Millar et al., 2002), strangulation during assault was associated with increased, while former romantic partner relationship with assailant was associated with decreased, receipt of health care among women with a high school education or less.

Differences in emergency care capabilities to serve sexual assault survivors are striking: screening and intervention at the time of emergency care to prevent the rare outcomes of pregnancy and infection (Holmes, Resnick, Kilpatrick, & Best, 1996; Jenny et al., 1990), respectively) have existed for more than 50 years, yet none are widely used in EDs to prevent PTS, depression, and other sequelae that occur in the majority of survivors. Such interventions offer the opportunity to dampen pathogenic processes during a key period of neuroplasticity; the above data indicate that for most women this will also be their only opportunity for preventive intervention. For example, prior studies by Resnick and colleagues of a brief video intervention offered to sexual assault survivors in the ED indicate promising results in the prevention of PTSD and depression, and particularly problematic substance use (Acierno, Resnick, Flood, & Holmes, 2003; Gilmore et al., 2019; Miller, Cranston, Davis, Newman, & Resnick, 2015; Resnick, Acierno, Kilpatrick, & Holmes, 2005; Resnick, Acierno, Amstadter, Self-Brown, & Kilpatrick, 2007). Indeed, a recent meta-analytic review indicated that these and other early cognitive behavioral preventions were efficacious in mitigating PTSS and related symptoms after sexual assault (Short, Morabito, & Gilmore, in press).

Sexual violence can result in both the kinds of psychiatric sequelae documented in this study, and a broader range of physical health effects (e.g., on cardiovascular health, sleep) that can last for decades (Kuwert et al., 2014; Thurston, Chang, Matthews, von Kanel, & Koenen, 2019). Because of this, identifying sexual violence history is important to the provision of optimal patient care. Consistent with prior qualitative and quantitative research, the current study identified shame and discomfort as the most commonly reported thematic barrier to disclosure of the assault to providers, and that lack of trust in providers also played a role (Blais, Brignone, Fargo, Galbreath, & Gundlapalli, 2018; Ullman, Foynes, & Tang, 2010; Zinzow & Thompson, 2011). Less common in prior research was the theme of feeling the assault was “irrelevant” to their care as a reason for non-disclosure. The frequent lack of reporting of recent sexual assault to providers due to shame, embarrassment, or fear of being judged is an important issue, as the majority of office health care visits in the US are at primary care clinics rather and specialty mental health visits are rare (Rui & Kang, 2020). These findings highlight the urgent need for further work to identify and implement universal screening practices and practices that make the clinic a safe and supportive space for disclosure (Cuevas, Balbo, Duval, & Beverly, 2018), such as including embedded mental health professionals (Fedynich, Cigrang, & Rauch, 2019).

This study had several limitations. First, outcomes for survivors who did not present for emergency care, or did not consent to the study, are unknown. Second, only adult women were included, because they comprise the vast majority of survivors seeking emergency care (Sabina & Ho, 2014; Smith et al., 2018). Further studies are needed to evaluate outcomes and receipt of health care in other populations. Third, there were a number of exclusion criteria for the current study necessary to test primary aims, such as the exclusion of women living with their assailant as they may experience repeated traumatization and thus have different trajectories of recovery after trauma. Unfortunately, this group is also at heightened risk for mental health concerns (Gilmore & Flanagan, 2020). As such, the current findings may not generalize to all women seeking emergency care after sexual assault. Fourth, health care utilization was assessed via self-report. However, the time of recall was relatively short, and this allowed us to assess a broad range of health care utilization and assault disclosure.

The results demonstrate a high burden of mental and physical sequelae in the weeks after sexual assault among women who receive emergency care. More than three quarters experienced clinically significant PTS, anxiety, or depressive symptoms, and the majority had new or worsening pain. Despite this, receipt of further health care following emergency care was uncommon, unrelated to substantive differences in need, and further limited in socially disadvantaged groups. Lack of disclosure to primary care providers was common among women who did receive care. These results highlight important gaps in the current care of women who are sexually assaulted, and the urgent need for emergency care-based interventions, improved linkages to care, and safe and supportive clinic environments for disclosure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the following National Institutes of Health Institutes: NIAMS, NINDS, OD (ORWH), NINR, NIMH, and NICHD (R01AR064700), a supplement from the OD (ORWH), and support from the Mayday Fund. The funders did not play a role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors thank the women sexual assault survivors who contributed their time and insight for this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of this protocol disclose that in the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis; was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, Sage Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Takeda; and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research. There are no other conflicts of interest to disclose

Data Availability Statement

Data will be shared upon reasonable request.

References

- Acierno R, Resnick HS, Flood A, & Holmes M (2003). An acute post-rape intervention to prevent substance use and abuse. Addictive Behaviors, 28(9), 1701–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman DR, Sugar NF, Fine DN, & Eckert LO (2006). Sexual assault victims: factors associated with follow-up care. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 194(6), 1653–1659. doi:S0002–9378(06)00337–1 [pii] 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agar K, Read J, & Bush J-M (2002). Identification of abuse histories in a community mental health centre: The need for policies and training. Journal of Mental Health, 11(5), 533–543. [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Shumway M, Morazes J, & Boccellari A (2011). Ethnic disparities in mental health treatment engagement among female sexual assault victims. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 20(4), 415–425. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, & Kilpatrick DG (2008). Service utilization and help seeking in a national sample of female rape victims. Psychiatric Services, 59(12), 1450–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Raat H, Jaddoe VW, Mautner E, & Korfage IJ (2018). Trajectories and predictors of women’s health-related quality of life during pregnancy: A large longitudinal cohort study. PloS One, 13(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijur PE, Latimer CT, & Gallagher EJ (2003). Validation of a verbally administered numerical rating scale of acute pain for use in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 10(4), 390–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais RK, Brignone E, Fargo JD, Galbreath NW, & Gundlapalli AV (2018). Assailant identity and self-reported nondisclosure of military sexual trauma in partnered women veterans. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy, 10(4), 470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisclair Demarble J, Fortin C, D’Antono B, & Guay S (2017). Gender differences in the prediction of acute stress disorder from peritraumatic dissociation and distress among victims of violent crimes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260517693000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Dworkin E, & Cabral G (2009). An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(3), 225–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, … Choi S (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas KM, Balbo J, Duval K, & Beverly EA (2018). Neurobiology of sexual assault and osteopathic considerations for trauma-informed care and practice. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 118(2), e2–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell D, Peterson R, Berliner L, Stewart T, Russo J, Whiteside L, & Zatzick D (2015). Factors associated with follow-up attendance among rape victims seen in acute medical care. Psychiatry, 78(1), 89–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Mont J, Macdonald S, White M, & Turner L (2013). Male victims of adult sexual assault: A descriptive study of survivors’ use of sexual assault treatment services. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(13), 2676–2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin ER, Menon SV, Bystrynski J, & Allen NE (2017). Sexual assault victimization and psychopathology: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 56(65–81). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedynich AL, Cigrang JA, & Rauch SA (2019). Brief Novel Therapies for PTSD - Treatment of PTSD in Primary Care In Sippel S. C. a. L. (Ed.), Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry (Vol. 6): Springer Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, & Flanagan JC (2020). Acute mental health symptoms among individuals receiving a sexual assault medical forensic exam: The role of previous intimate partner violence victimization. Archives of women’s mental health, 23(1), 81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, Walsh K, Frazier P, Meredith L, Ledray L, Davis J, … Jaffe AE (2019). Post-sexual assault mental health: a randomized clinical trial of a video-based intervention. Journal of interpersonal violence, 0886260519884674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, & Best CL (1996). Rape-related pregnancy: estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 175(2), 320–324; discussion 324–325. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70141-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Bortsov AV, Ballina LE, Orrey DC, Swor RA, Peak DA, … McLean SA (2015). Chronic Widespread Pain after Motor Vehicle Collision Typically Occurs via Immediate Development and Non-Recovery: Results of an Emergency Department-Based Cohort Study. Pain, In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jenny C, Hooton TM, Bowers A, Copass MK, Krieger JN, Hillier SL, … Holmes KK (1990). Sexually transmitted diseases in victims of rape. N Engl J Med, 322(11), 713–716. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003153221101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, & Calhoun KS (1994). Somatic symptoms, social support, and treatment seeking among sexual assault victims. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 62(2), 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwert P, Glaesmer H, Eichhorn S, Grundke E, Pietrzak RH, Freyberger HJ, & Klauer T (2014). Long-term effects of conflict-related sexual violence compared with non-sexual war trauma in female World War II survivors: a matched pairs study. Arch Sex Behav, 43(6), 1059–1064. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0272-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen ML, Hilden M, & Lidegaard Ø (2015). Sexual assault: a descriptive study of 2500 female victims over a 10‐year period. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 122(4), 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Bowen A, Bowen R, Balbuena L, Feng C, Bally J, & Muhajarine N (2019). Mood instability during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review. Archives of women’s mental health, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden JA (2011). Clinical practice. Care of the adult patient after sexual assault. The New England journal of medicine, 365(9), 834–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1102869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SA, Soward AC, Ballina LE, Rossi C, Rotolo S, Wheeler R, … Liberzon I (2012). Acute severe pain is a common consequence of sexual assault. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society, 13(8), 736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengeling MA, Booth BM, Torner JC, & Sadler AG (2015). Post–sexual assault health care utilization among OEF/OIF servicewomen. Medical Care, 53, S136–S142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook: sage. [Google Scholar]

- Millar G, Stermac L, & Addison M (2002). Immediate and delayed treatment seeking among adult sexual assault victims. Women and Health, 35(1), 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Cranston CC, Davis JL, Newman E, & Resnick H (2015). Psychological outcomes after a sexual assault video intervention: A randomized trial. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 11(3), 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RE, & Truman JL (2018). Criminal Victimization, 2017. Retrieved from

- National Center for PTSD. (2019). PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

- Parekh V, & Brown CB (2003). Follow up of patients who have been recently sexually assaulted. Sexually transmitted infections, 79(4), 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, & Mays N (1995). Qualitative research: reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ, 311(6996), 42–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Davidson TM, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, & Resnick HS (2014). Predictors of using mental health services after sexual assault. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(3), 331–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick H, Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, & Holmes M (2005). Description of an early intervention to prevent substance abuse and psychopathology in recent rape victims. Behavior Modification, 29(1), 156–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Acierno R, Amstadter AB, Self-Brown S, & Kilpatrick DG (2007). An acute post-sexual assault intervention to prevent drug abuse: Updated findings. Addictive Behaviors, 32(10), 2032–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Murdock T, & Walsh W (1992). A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 455–475. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rui P, & Kang K (2020). National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf

- Sabina C, & Ho LY (2014). Campus and college victim responses to sexual assault and dating violence: Disclosure, service utilization, and service provision. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15(3), 201–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedov ID, Cameron EE, Madigan S, & Tomfohr-Madsen LM (2018). Sleep quality during pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 38, 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short NA, Morabito DM, & Gilmore AK (in press). Secondary Prevention for Posttraumatic Stress and Related Symptoms among Women who Experienced Recent Sexual Assault: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Depression and Anxiety. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short NA, Sullivan J, Soward A, Bollen K, Liberzon I, Martin S, … McLean SA (2019). Protocol for the first large-scale emergency care-based longitudinal cohort study of recovery after sexual assault: the Women’s Health Study. BMJ Open, 9(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, Merrick MT, Wang J, Kresnow M, & Chen J (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief - Updated Release. Retrieved from Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Lang AJ, Laffaye C, Satz LE, Lenox RJ, & Dresselhaus TR (2004). Relationship of sexual assault history to somatic symptoms and health anxiety in women. General hospital psychiatry, 26(3), 178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R. C. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Thurston RC, Chang Y, Matthews KA, von Kanel R, & Koenen K (2019). Association of Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault With Midlife Women’s Mental and Physical Health. JAMA internal medicine, 179(1), 48–53. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Foynes MM, & Tang SSS (2010). Benefits and barriers to disclosing sexual trauma: A contextual approach: Taylor & Francis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Blake D, Schnurr P, Kaloupek D, Marx B, & Keane T (2013). The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Wolfe F (2003). Pain extent and diagnosis: development and validation of the regional pain scale in 12,799 patients with rheumatic disease. Journal of Rheumatology, 30(2), 369–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE (1992). The sociocultural context of African American and White American women’s rape. Journal of Social Issues, 48(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R (2002). Post-traumatic stress disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(2), 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young-Wolff KC, Sarovar V, Klebaner D, Chi F, & McCaw B (2018). Changes in Psychiatric and Medical Conditions and Health Care Utilization Following a Diagnosis of Sexual Assault. Medical Care, 56(8), 649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Resnick HS, Amstadter AB, McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Drug- or Alcohol-Facilitated, Incapacitated, and Forcible Rape in Relationship to Mental Health Among a National Sample of Women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(12), 2217–2236. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, & Thompson M (2011). Barriers to reporting sexual victimization: Prevalence and correlates among undergraduate women. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 20(7), 711–725. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.