Abstract

Introduction

The Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) database, created in 2010 by the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT), compiles data recorded by medical toxicologists. In January 2017, the data field for transgender (and if transgender, male-to-female or female-to-male) was added to the ToxIC form. Little is known regarding trends in poisonings among transgender patients. We sought to review consultations managed by a bedside toxicologist and provide descriptive data in trends among types of exposures within the transgender demographic.

Methods

A retrospective ToxIC database evaluation of cases in which the patient identified as transgender were reviewed from January 2017–June 2019 and descriptive demographics reported.

Results

The registry contained 113 cases that involved transgender patients. Of those with complete data, 41 (36.6%) were male-to-female, 68 (60.7%) were female-to-male, and 3 (2.7%) identified as gender non-conforming. Of those with complete data, the most common reason for encounter was intentional use of a pharmaceutical drug (N = 97, 85.8%), of which 85 (87.6%) were classified as intentional pharmaceutical use intended for self-harm. Analgesics were the most common class of drugs used out of those reported (N = 24, 22%). Forty-six (90.2%) patients aged 13–18 with complete data were identified as encounters due to self-harm. Attempt at self-harm was the most common reason for intentional pharmaceutical encounter among the sample of transgender patients with complete data (N = 85, 87.6%); with female-to-male patients having an N = 53 (77.9%).

Conclusion

Among transgender patients in the ToxIC registry, the most common primary reason for the encounter was intentional use of a pharmaceutical drug intended for self-harm. In this small cohort, there were some age and transition differences in prevalence. These findings may inform poisoning prevention practices as well as sex- and gender-based management of patients in this vulnerable population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13181-020-00789-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Transgender, Drug misuse and abuse, ToxIC, Toxicological exposure

Introduction

There is a paucity of data regarding sex and gender differences in drug overdose presentations and outcomes, specifically transgender patients [1]. Transgender patients are those defined as persons whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth [2]. The existing data on sex- and gender-based suicide reveals that cis-males are more likely to complete a suicide attempt, whereas cis-females are more likely to attempt suicide [3, 4]. This data also revealed that of the studied population, pharmacological misuse and abuse was the most common means of suicide (42% of suicide attempts), but males tended to favor more mechanical means of suicide such as hanging and asphyxiation, and females tended to use pharmacologic means [3]. Previous studies focused primarily on traditional/biologic gender dichotomy (male and female), however fail to address the gender non-conforming population [3, 5, 6]. Gender-specific data describing types of poisonings and outcomes is lacking, especially for transgender patients.

It is well documented that transgender patients face discrimination and report mistreatment when seeking medical care [7–9]. Samuels et al. found that transgender patients commonly reported mistreatment, such as having to unnecessarily reaffirm their gender to caregivers, improper documentation that leads to embarrassment, a lack of, or different privacy than other patients, and even blatant verbal discrimination [7]. These forms of mistreatment demonstrate a disconnect, or lack of understanding, between providers and this patient population.

Additionally, care providers are being inadequately trained when it comes to this vulnerable population. A recent survey of the US Obstetrics and Gynecology residency programs showed only half of the responding program directors reported offering clinical training in transgender healthcare [10]. In emergency medicine residencies, education specific to this domain was included in the curriculum in as few as one third of the programs surveyed [2]. Additionally, a survey of practicing physicians within the field of emergency medicine, where these patients frequently receive care, showed that 88% of Emergency Department (ED) physicians had encountered transgender and gender non-conforming patients, yet only 83% reported any formal education in the matter, and less than 3% were aware that transgender patients often experience unnecessary exams when seeking care [11]. This lack of education and mistreatment of patients represents a significant disconnect between providers and the populations they serve, as well as contributes to the barriers to further sex- and gender-based care research [2]. This is an important knowledge gap to address, as there are currently 1.4 million adults in the USA that identify as transgender [12]. Studies have shown higher rates of suicide among transgender patients compared to the general population, with as many as 37% of transgender patients reporting previous suicide attempts due to discrimination [8, 13].

To narrow the gap in existing health care disparities, research specific to the transgender population is necessary [1]. Understanding the importance of biological sex and gender-identity and designing studies that help providers personalize patient care based on their findings will be crucial in providing appropriate medical care for this growing population.

Beyond the need to fill gaps in sex and gender research in Emergency Medicine (EM), the clinical practice of EM still faces gaps in the integration of sex and gender aspects of patient assessment and treatment. For this reason, we set out to review medical encounters managed by a bedside toxicologist within the transgender demographic that were identified in the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) database.

Methods

The ToxIC database, a unique toxicology database created in 2010 by the ACMT, compiles data recorded by medical toxicologists and is maintained by ACMT [14]. This database is composed of voluntary entries from medical toxicology consults, both outpatient and inpatient, from any of the 50 participating sites [14]. In order to obtain consistent information from all consults, all toxicologists complete a standard form made by ACMT, which is then entered electronically into the database. In January 2017, the data field for transgender (and if transgender, male-to-female, female-to-male or gender-nonconforming) was added to the ToxIC form in order to provide representation and data for this patient population [15].

This study is a retrospective database review of patient cases submitted to the ACMT ToxIC database between January 2017 and June 2019, who reporting toxicologist identified as transgender. Patient cases were considered to have complete data if the sex variable was complete as “transgender.” However, within the 113 cases that had this variable completed as “transgender,” one was missing the ‘if transgender” variable specifying male-to-female, female-to-male, or gender-nonconforming, resulting in 112 cases with this variable completed.

The goal of this review is to determine the types of poisonings, the context of toxicity (i.e., accidental or intentional), and outcomes among transgender patients. This data is reported voluntarily by participating medical toxicology sites involved in the ToxIC Registry, and cases are reported if bedside consultation by the medical toxicology service occurred. Data collection proceeded via a standardized form (Appendix). Data collected in this form include patient demographics, encounter information, details of toxicological exposure, symptoms, and types of treatment given (Appendix). All cases are de-identified as they are entered into the registry. Using the data collected, descriptive analysis was performed to obtain frequencies of and highlight specific variables of interest for this study. These variables of focus were evaluated between age groups within the study sample and included proportion of consults for intentional poisoning and intent to self-harm. The age groups are reported in the manner that they are collected in the ToxIC database, broken down as the following: < 2 years, 2–6 years, 7–12 years, 13–18 years, 19–65 years, 66–89 years, and > 89 years. Proportion of consults for intentional poisoning with intent to self-harm between patients who were male-to-female transgender patients and female-to-male transgender patients was examined. This study was reviewed by the lead author’s hospital Institutional Review Board at Lehigh Valley Hospital and, due to the nature of the database, was assigned a determination of not human research.

Results

Excluding those with missing data, the registry had 113 cases that involved transgender patients between January 1, 2017, and June 2019. Of those with complete data, 41 (36.6%) were male-to-female, 68 (60.7%) were female-to-male, and 3 (2.7%) identified as gender-nonconforming. Table 1 depicts the demographics of these patients with complete data, including their age, race, and ethnicity: 65 (57.5%) were reported as Caucasian, and 31 (27.4%) were reported as unknown/uncertain.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Entire Sample (N = 113) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total N | N (percentage of variable) |

| Age | 113 | |

| < 2 years | 0 | |

| 2–6 years | 0 | |

| 7–12 years | 1 (0.9) | |

| 13–18 years | 51 (45.1) | |

| 19–65 years | 60 (53.1) | |

| 66–89 years | 1 (0.9) | |

| > 89 years | 0 | |

| Transgender | 112 | |

| Male-to-female | 41 (36.6) | |

| Female-to-male | 68 (60.7) | |

| Gender non-conforming | 3 (2.7) | |

| Race | 113 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (0.9) | |

| Asian | 5 (4.4) | |

| Australian Aboriginal | 0 | |

| Black/African | 7 (6.2) | |

| Caucasian | 65 (57.5) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.9) | |

| Mixed | 3 (2.7) | |

| Other | 0 | |

| Unknown/uncertain | 31 (27.4) | |

| Multiple races | 0 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 113 | |

| Yes | 10 (8.8) | |

| No | 67 (59.3) | |

| Unknown | 36 (31.9) | |

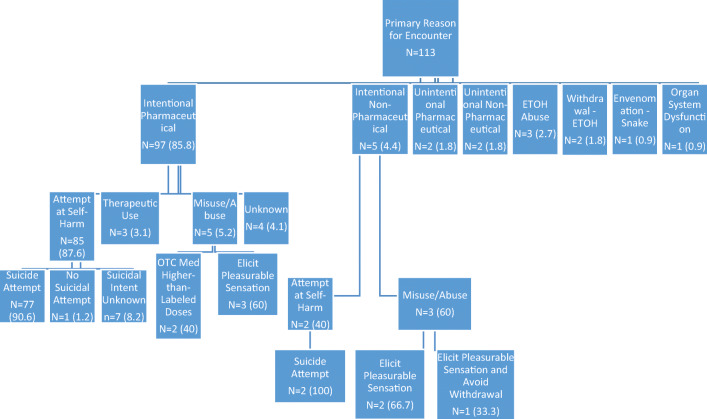

Both Fig. 1 and Table 2 depict the encounter information for all of these cases. The most common reason for the encounter of patients with this data point completed was intentional use of a pharmaceutical drug (N = 97, 85.8%), of which 85 (87.6%) were classified as intentional pharmaceutical use intended for self-harm.

Fig. 1.

Primary reason for encounter flow diagram.

Table 2.

Encounter information.

| Entire sample (N = 113) | ||

| Variable | Total N | N (percentage of variable) |

| Encounter location—attending (inpatient) | 23 | |

| ED | 0 | |

| Obs unit | 0 | |

| Hospital floor | 6 (26.1) | |

| ICU | 12 (52.2) | |

| Outpatient/clinic/office consultation | 0 | |

| ED and hospital floor | 1 (4.3) | |

| ED and ICU | 2 (8.7) | |

| Hospital floor and ICU | 2 (8.7) | |

| Encounter location—consult (ED/inpatient) | 90 | |

| ED | 47 (52.2) | |

| Obs unit | 3 (3.3) | |

| Hospital floor | 16 (17.8) | |

| ICU | 16 (17.8) | |

| Outpatient/clinic/office consultation | 0 | |

| ED and hospital floor | 6 (6.7) | |

| ED and ICU | 2 (2.2) | |

| Hospital floor and ICU | 0 | |

| Primary reason for encounter | 113 | |

| Intentional pharmaceutical | 97 (85.8) | |

| Intentional non-pharmaceutical | 5 (4.4) | |

| Unintentional pharmaceutical | 2 (1.8) | |

| Unintentional non-pharmaceutical | 2 (1.8) | |

| Malicious/criminal | 0 | |

| ETOH abuse | 3 (2.7) | |

| Withdrawal—ETOH | 2 (1.8) | |

| Withdrawal—opioids | 0 | |

| Withdrawal—sedative-hypnotics; | 0 | |

| Withdrawal—cocaine/amphetamines | 0 | |

| Withdrawal—other | 0 | |

| Envenomation—snake | 1 (0.9) | |

| Envenomation—spider | 0 | |

| Envenomation—scorpion | 0 | |

| Envenomation—other | 0 | |

| Marine/fish poisoning | 0 | |

| Organ system dysfunction | 1 (0.9) | |

| Interpretation of toxicology lab data | 0 | |

| Occupational evaluation | 0 | |

| Environmental evaluation | 0 | |

| Unknown | 0 | |

| Surveillance | 0 | |

| Adverse drug reaction | 0 | |

| Medication error | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | |

| Primary reason for encounter—Int Pharm | 97 | |

| Attempt at self-harm | 85 (87.6) | |

| Misuse/abuse | 5 (5.2) | |

| Therapeutic use | 3 (3.1) | |

| Unknown | 4 (4.1) | |

| Primary reason for encounter—Int Pharm—attempted self-harm | 85 | |

| Suicide attempt | 77 (90.6) | |

| No suicidal attempt | 1 (1.2) | |

| Suicidal intent unknown | 7 (8.2) | |

| Primary reason for encounter—Int Pharm—misuse/abuse | 5 | |

| Use of Rx med w/o Rx | 0 | |

| Taking Rx med in higher-than-prescribed doses | 0 | |

| Taking OTC med in higher-than-labeled doses | 2 (40) | |

| Taking excess doses or using other’s meds | 0 | |

| Taking med to elicit pleasurable sensation | 3 (60) | |

| Taking med to avoid withdrawal | 0 | |

| Multiple reasons | 0 | |

| Primary Reason for Int Non-Pharm | 5 | |

| Attempt at Self-Harm | 2 (40) | |

| Misuse/Abuse | 3 (60) | |

| Use for Therapeutic Intent | 0 | |

| Drug Concealment | 0 | |

| Unknown | 0 | |

| Primary reason for Int Non-Pharm—attempted self-harm | 2 | |

| Suicide attempt | 2 (100) | |

| No suicidal attempt | 0 | |

| Suicidal intent unknown | 0 | |

| Primary reason for Int Non-Pharm—misuse/abuse | 3 | |

| Taking substance to elicit pleasurable sensation | 2 (66.7) | |

| Taking substance to avoid withdrawal | 0 | |

| Taking substance to elicit pleasurable sensation and to avoid withdrawal | 1 (33.3) | |

| Was case related to medication error | 113 | |

| Yes | 0 | |

| No | 112 (99.1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) | |

| Was it an ADR | 113 | |

| Yes | 1 (0.9) | |

| No | 110 (97.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.8) | |

Analgesics were the most common class of drugs reported, with 24 reported cases out of those available (22%). Other common exposures in patients with completed data included antidepressants (N = 19, 17.4%), anticholinergic/antihistamines (N = 12, 11%), antipsychotics (N = 10, 9.2%), and alcohol ethanol (N = 7, 6.4%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toxicological exposure information.

| Entire sample (N = 113) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total N | N (percentage of variable) |

| Toxicological exposure | 113 | |

| Yes | 109 (96.5) | |

| No | 3 (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) | |

| Single or multiple exposure? | 109 | |

| Single exposure | 56 (51.4) | |

| Multiple exposure | 53 (48.6) | |

| Agent #1 class | 109 | |

| Alcohol ethanol | 7 (6.4) | |

| Alcohol toxic | 0 | |

| Amphetamine-like hallucinogen | 0 | |

| Analgesic | 24 (22) | |

| Anesthetic | 0 | |

| Anticholinergic/antihistamine | 12 (11) | |

| Anticoagulant | 1 (0.9) | |

| Anticonvulsant | 4 (3.7) | |

| Antidepressant | 19 (17.4) | |

| Antimicrobials | 1 (0.9) | |

| Antipsychotic | 10 (9.2) | |

| Cardiovascular | 2 (1.8) | |

| Caustic | 0 | |

| Chelator | 0 | |

| Chemotherapeutic and immune | 1 (0.9) | |

| Cholinergic/parasympathomimetic | 0 | |

| Cough and cold | 4 (3.7) | |

| Diabetic med | 2 (1.8) | |

| Endocrine | 0 | |

| Envenomation | 1 (0.9) | |

| Foreign objects | 0 | |

| Fungicide | 0 | |

| Gases/vapors/irritants/dust | 0 | |

| GI | 1 (0.9) | |

| Herbals/dietary supps/vitamins | 1 (0.9) | |

| Herbicide | 0 | |

| Household | 3 (2.8) | |

| Hydrocarbon | 0 | |

| Insecticide | 0 | |

| Lithium | 3 (2.8) | |

| Marine toxin | 0 | |

| Metals | 0 | |

| Opioid | 4 (3.7) | |

| Other non-pharmaceutical | 0 | |

| Other pharmaceutical | 1 (0.9) | |

| Parkinson’s med | 0 | |

| Photosensitizing agents | 0 | |

| Plants and fungi | 0 | |

| Psychoactive | 1 (0.9) | |

| Pulmonary | 0 | |

| Rodenticide | 0 | |

| Sed-hypnotic/muscle relaxant | 3 (2.8) | |

| Sympathomimetic | 3 (2.8) | |

| WMD/NBC/riot | 0 | |

| Unknown agent | 1 (0.9) | |

| Route of administration | 109 | |

| Oral | 95 (87.2) | |

| Inhalation | 2 (1.8) | |

| Parenteral | 3 (2.8) | |

| Intranasal | 1 (0.9) | |

| Dermal | 2 (1.8) | |

| Unknown | 5 (4.6) | |

| Rectal | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (0.9) | |

| Type of exposure | 107 | |

| Acute | 78 (72.9) | |

| Chronic | 3 (2.8) | |

| Acute-on-chronic | 20 (18.7) | |

| Unknown | 6 (5.6) | |

There were no reported deaths in any of the cases with data available for this variable; this variable was missing for one patient. The most commonly reported signs/symptoms involved the nervous system (Table 4). Of the reported nervous system complications, 24 cases (25.3%) were coded with the single symptom of coma, 24 (25.3%) had multiple nervous system symptoms, 9 (9.5%) were coded with the single symptom of agitation, and 27 (28.4%) had reported none. The most commonly reported vital sign abnormality was tachycardia, with 16 reported cases out of those available (16.8%). Regarding treatment interventions, 7 (6.2%) of the patients with data available required intubation. Out of the 76 patients that required pharmacologic support, 26 (34.2%) were treated with benzodiazepines and 5 (6.6%) reported multiple pharmacological treatments (Table 4).

Table 4.

Complications.

| Entire sample (N = 113) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total N | N (percentage of variable) |

| Major vital sign abnormalities | 95 | |

| Hypotension | 0 | |

| Hypertension | 0 | |

| Bradycardia | 3 (3.2) | |

| Tachycardia | 16 (16.8) | |

| Tachypnea | 0 | |

| Bradypnea | 1 (1.1) | |

| Hyperthermia | 0 | |

| Hypothermia | 0 | |

| None | 72 (75.8) | |

| Multiple symptoms | 3 (3.2) | |

| Cardiovascular | 95 | |

| Ventricular dysrhythmias | 0 | |

| Prolonged QTc | 4 (4.2) | |

| Prolonged QRS | 1 (1.1) | |

| None | 90 (94.7) | |

| Nervous system | 95 | |

| Agitation | 9 (9.5) | |

| Delirium/psychosis | 4 (4.2) | |

| Coma | 24 (25.3) | |

| Seizures | 2 (2.1) | |

| Hyperreflexia/clonus/tremor | 3 (3.2) | |

| EPS/dystonia/rigidity | 0 | |

| Hallucinations | 2 (2.1) | |

| Numbness/paresthesia | 0 | |

| None | 27 (28.4) | |

| Multiple symptoms | 24 (25.3) | |

| Death | 112 | |

| Yes | 0 | |

| No | 112 (100) | |

| Life support withdrawn | – | |

| Yes | – | |

| No | – | |

| Unknown | – | |

| Pharmacologic support | 76 | |

| Vasopressors | 0 | |

| Benzodiazepines | 26 (34.2) | |

| Opioids | 1 (1.3) | |

| Neuromuscular blockers | 0 | |

| Glucose | 2 (2.6) | |

| Bronchodilators | 1 (1.3) | |

| Steroids | 0 | |

| Anticonvulsants | 0 | |

| Antiarrhythmics | 0 | |

| None | 40 (52.6) | |

| Antipsychotics | 1 (1.3) | |

| Multiple treatments | 5 (6.6) | |

| CPR | 113 | |

| Yes | 0 | |

| No | 113 (100) | |

| ECMO | 113 | |

| Yes | 0 | |

| No | 113 (100) | |

| Intubation/ventilation | 113 | |

| Yes | 7 (6.2) | |

| No | 106 (93.8) | |

Among the 51 patients aged 13–18 with data available, 46 (90.2%) were reported to have attempted self-harm as primary reason for encounter. Within the 60 patients aged 19–65 with data available, 37 (61.7%) were reported to have attempted self-harm with a pharmaceutical as the primary reason for encounter.

In the 41 male-to-female transgender patients with completed data, 28 (68.3%) had intentional self-harm with a pharmaceutical agent as the reported reason for the encounter. Of the 68 female-to-male transgender patients with complete data, 53 (77.9%) were reported to have intent for self-harm with a pharmaceutical agent as the primary reason for encounter.

Discussion

Drug overdoses and outcomes in the transgender population represent a significant gap in the existing literature. To our knowledge, this is the first presentation of data about specific agents of poisoning, complications, and subsequent outcomes of transgender patients [15]. This study is consistent with the research agenda set forth by EM researchers who convened at the Academic Emergency Medicine’s 2014 Consensus Conference, “Gender Specific Research in Emergency Care” [16]. They sought to develop a sex- and gender-based medicine plan to serve as a guide for emergency care research into expanding the assessment of the influence that sex and gender have on the delivery of clinical care, healthcare utilization, disease presentation, and treatment responses and outcomes [16].

Current studies consistently indicate that this population is at an increased risk of suicide [17]. The high rate of intentional self-harm is not surprising given marginalization of this population. In our study (albeit small), 90.2% of transgender patients within the age group of 13–18 years old reported attempt at self-harm as the primary reason for encounter. Additionally, among those who identified as female-to-male transgender, 77.9% reported attempt at self-harm as the primary reason for encounter. Our study is consistent with prior research, which describes a difference in rates of suicidal behavior between female-to-male adolescents, male-to-female adolescents, and those who identify as not exclusively male or female; all three of these subgroups have higher suicide rates than male or female adolescents [18]. Our data, along with existing data, supports the need for further research into the potential increased risk of suicidality among female-to-male transgender individuals. Literature also exists regarding the specific risk factors related to transgender suicidality. Overall, the risk factors can be summed up as victimization related to the transgender population and subsequently broken down into examples such as exposure to trans-associated violence, offensive treatment, dissatisfaction with social support network, and a deficit of practical support that increase suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [19]. From a clinician standpoint, facilitating the resources for this vulnerable population before they are evaluated for overdose would be advantageous; however, bedside interventions to prevent future self-harm attempts are also important.

Ongoing data collection within the ToxIC database will enable identification of trends among transgender patients managed by a toxicologist, with the goal of developing effective strategies to intervene on at risk transgender individuals prior to poisoning events. The data collected through the ToxIC registry currently only breaks down the gender category “transgender” into male-to-female, female-to-male, or gender-nonconforming. It would be helpful for further study to gather more information on whether patients have undergone surgical procedures or hormonal therapy because it has been shown that rates of suicidality and utilization of mental health services may differ based on transition-related medical interventions [20, 21]. As the population that identifies as transgender grows, it is important that we also continue to grow the collective knowledge of how best to care for our transgender patients to reduce known minority population health care disparities. This study of transgender poisonings will inform and contribute to an ongoing effort in the field of EM and Medical Toxicology to study the effect that sex and gender have on patient care and outcomes.

Limitations

There are several key limitations with use of the ToxIC registry. Cases are submitted to the registry by a medical toxicologist, and thus patients who are not evaluated by a toxicologist at the bedside are excluded from this registry. This eliminates patients who present to hospitals that do not have a medical toxicology service and also eliminates patients whom medical toxicology is not consulted, who could include patients who are pronounced dead on, or shortly after arrival. Submission of cases is voluntary, and there are no metrics to determine what percentage of poisoning cases evaluated by bedside toxicologists are actually submitted to the registry. Submission may also be impacted by the acuity of the patient, which may affect how toxicology resources are allocated to patient care and data collection. The impact of generalizability of the data across the nation (for instance there might be a difference in transgender patient ingestions between Little Rock and Los Angeles) is not known and factors into the interpretation of this work.

The accuracy of the data is also limited by patients’ willingness to volunteer information to the medical staff regarding their gender, substances ingested, and intent of ingestion. This openness may be impacted by the medical staff member’s ability to ask questions in a non-judgmental manner that encourages full and honest answers from the patient, as well as the accuracy of the documentation and submission of information obtained to the ToxIC registry. Additionally, patients who identify as transgender may describe their gender as male or female, and not female-to-male or male-to-female. This would mean these patients would not be entered into the database as transgender. Additionally, the field was just added to the TOXIC form in 2017, so the number of cases in the registry is still relatively small and is accompanied by missing data which precludes stronger inferences. It is important to remember that this data is specific to transgender patients who required a toxicology consult, so data, such as self-harm may not be generalizable to all of the transgender population.

No patient information is included in data submission to the registry, and thus there is no mechanism available or in place to confirm accuracy in comparing case submissions to a patient’s medical record. Hence, it is impossible to confirm the accuracy of reported data. Finally confirmatory testing is often unavailable among cases reported to ToxIC, so the identification of substances involved in cases cannot be confirmed, and case data relies upon what is known or assumed by the reporting toxicologist.

Finally, this investigation was performed to gather preliminary data designed to inform the approach to data collection around transgender patient cases submitted to the ToxIC registry. This descriptive data may help inform which additional data points could be added to the registry data form including current or prior use of any hormone-based treatments, gender-affirming surgery, and age of initiation of gender transition. Given the specific focus of this study was to inform future data collection, we did not perform a comparison to non-transgender patients submitted to the registry during this time period. This is a potential area of future study.

Conclusion

Among transgender patients in the ToxIC registry, the most common primary reason for the encounter was intentional use of a pharmaceutical drug intended for self-harm. Analgesics, followed by antidepressants were the most commonly involved pharmaceutical drugs. In this small cohort, there were some age and transition (male-to-female versus female-to-male) differences in prevalence.

Data describing sex- and gender-specific differences in types of exposures/ingestions, as well as outcomes, may inform poisoning prevention practices as well as sex- and gender-based management of patients in this vulnerable population.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 13 kb)

Sources of Funding

This study, in part, was funded by an unrestricted grant, the Dorothy Rider Pool Trust for Health Research and Education community foundation grant (Grant Number 20121584-001).

Appendix Variables for ToxIC sex/transgender study

Age: < 2 years; 2–6 years; 7–12 years; 13–18 years; 19–65 years; 66–89 years; > 89 years

Sex: female or male or transgender

If transgender: M ➔ F or F ➔ M

Pregnancy status: yes or no

Race: American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Australian Aboriginal, Black/African, Caucasian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, mixed, other, unknown/uncertain

Hispanic/Latino: yes or no

Location of encounter: ED vs. ICU vs. hospital floor vs. outpatient vs. multiple locations listed

Reason for encounter:

Intentional pharmaceutical: self-harm (suicidal versus non-suicidal); misuse/abuse: prescription vs. OTC vs. medical treatment vs. pleasure vs. treating/avoiding withdrawal vs. therapeutic use vs. unknown.

Intentional non-pharmaceutical: self-harm (suicidal versus non-suicidal); misuse/abuse: prescription vs. OTC vs. medical treatment vs. pleasure vs. treating/avoiding withdrawal vs. therapeutic use vs. unknown; drug concealment

Unintentional pharmaceutical (unintended use of approved medication)

Unintentional non-pharmaceutical (unintended use of a substance that is not an approved medication)

Malicious/criminal

Ethanol abuse

Envenomation: scorpion vs. snake vs. spider vs. other

Marine/fish poisoning

Withdrawal: etoh vs. opioids vs. sedative-hypnotics vs. stimulants vs. other

Environmental exposure

Medication error: yes or no

Adverse drug reaction (to normal dosing): yes or no

Unknown

Single exposure vs. multiple exposure

Primary agent class:

Sedative hypnotic (non-opioid)

Antidepressants

Opioids/opiates—prescription

Opioids/opiates—illicit

Alcohols

Antipsychotics

Sympathomimetics—prescription

Sympathomimetics—illicit

Other analgesics

Cardiac medications

Anticholinergics

Psychoactive substances

Anticonvulsants

Diabetes medications

Gases

Household caustics

Other household products

Hydrocarbons

Cough/cold medications

Anesthetics

Pesticides

Metals

Anticoagulants

Antibiotics

Gastrointestinal meds

Supplements/vitamins

Plants

Envenomations

Paralytics/neuromuscular blockade

Other

Route of exposure: oral vs. inhalation vs. parenteral vs. unknown vs. intranasal vs. dermal

Type of exposure: acute vs. chronic vs. acute on chronic vs. unknown

Major vital sign abnormalities: hypotension vs. hypotension vs. bradycardia vs. tachycardia vs. tachypnea vs. bradypnea vs. hyperthermia vs. hypothermia

Cardiovascular toxicity: ventricular dysrhythmias vs. prolonged QT vs. wide QRS

CNS toxicity: agitation/delirium/psychosis vs. coma vs. seizures vs. hyperreflexia/clonus/tremor vs. EPS/dystonia/rigidity

Death: yes/no

Withdrawal of support: yes/no

Pharmacologic support: pressors vs. benzos vs. opioids vs. neuromuscular blockers vs. glucose vs. bronchodilators vs. steroids vs. anticonvulsants vs. antiarrhythmics

CPR: yes/no

Intubation/ventilation: yes/no

ECMO: yes/no

Authors Contribution

All authors provided substantial contributions to the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

None. The authors have no outside support information, conflicts or financial interest to disclose. This study, in part, was funded by an unrestricted grant, the Dorothy Rider Pool Trust for Health Research and Education community foundation grant (Grant Number 20121584-001). An abstract of this content, in part, was presented by Mikayla Hurwitz at the American College of Medical Toxicology Annual Scientific Meeting March 13-15, 2020 in New York, NY. The authors acknowledge her input in preparation and presentation of this abstract.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stall R, Matthews DD, Friedman MR, Kinsky S, Egan JE, Coulter RW, Blosnich JR, Markovich N. The continuing development of health disparities research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):787–789. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jalali S, Sauer L. Improving care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients in the emergency department. Ann of Emerg Med. 2015;66(4):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsirigotis K, Gruszczynski W, Tsirigotis M. Gender differences in methods of suicide attempts. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(8):65–70. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canetto SS, Sakinofsky I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1998;28(1):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGregor AJ, Greenberg M, Safdar B, Seigel T, Hendrickson R, Poznanski S, et al. Focusing a gender lens on emergency medicine research: 2012 update. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:313–320. doi: 10.1111/acem.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safdar B, McGregor AJ, McKe SA, et al. Inclusion of gender in emergency medicine research. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:e1–e4. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuels EA, Tape C, Garber N, Bowman S, Choo EK. ‘Sometimes You Feel Like the Freak Show’: a qualitative assessment of emergency care experiences among transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raifman J. Sanctioned stigma in health care settings and harm to LGBT youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(8):713–714. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Care of the transgender patient. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(1):ITC1–ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC201907020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rush S, Vinekar K, Chiang S, Schiff M. OB/GYN Residency training in transgender healthcare: a survey of U.S. program directors. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:41S–42S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000546619.74315.3c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chisolm-Straker M, Willging C, Daul AD, McNamara S, Sante SC, Shattuck DG, 2nd, Crandall CS. Transgender and gender-nonconforming patients in the emergency department: what physicians know, think, and do. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores A, Herman J, Gates G, and Brown T. How many adults identify as transgender in the U.S. The Williams Institute. 2016. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdfAccessed 02/24/2019

- 13.Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Wojcio S, Jones KT, Bossarte RM. Mortality among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses in the Veterans Health Administration, FKY 2000–2009. LGBT Health. 2014;1(4):269–276. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrugia LA, Rhyee SH, Campleman SL, Ruha AM, Weigand T, Wax PM, et al. The Toxicology Investigators Consortium Case Registry-the 2015 experience. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12(3):224–247. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0580-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrugia LA, Rhyee SH, Campleman SL, Judge B, Kao L, Pizon A, Porter L, Riederer AM, et al. The Toxicology Investigators Consortium Case Registry-the 2017 annual report. J Med Toxicol. 2018;14(3):182–211. doi: 10.1007/s13181-018-0679-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg MR, Safdar B, Choo EK, McGregor AJ, Becker LB, Cone DC. Future directions in sex- and gender-specific emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:1339–1342. doi: 10.1111/acem.12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceniti AK, Heinecke N, McInerney SJ. Examining suicide-related presentations to the emergency department. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Toomey RB, Syvertsen AK, Shramko M. Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4). 10.1542/peds.2017-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zeluf G, Dhejne C, Orre C, Mannheimer LN, Deogan C, Höijer J, Winzer R, Thorson AE. Targeted victimization and suicidality among trans people: a web-based survey. LGBT Health. 2018;5(3):180–190. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bränström R, Pachankis JE. Reduction in mental health treatment utilization among transgender individuals after gender-affirming surgeries: a total population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010080. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Tucker RP, Testa RJ, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Blosnich JR, Lehavot K. Hormone therapy, gender affirmation surgery, and their association with recent suicidal ideation and depression symptoms in transgender veterans. Psychol Med. 2018;48(14):2329–2336. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 13 kb)