Abstract

Formation of Aβ oligomers and fibrils plays a central role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. There are two major forms of Aβ in the brain: Aβ42 and Aβ40. Aβ42 is the major component of the amyloid plaques, but the overall abundance of Aβ40 is several times that of Aβ42. In vitro experiments show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 affect each other’s aggregation. In mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease, overexpression of Aβ40 has been shown to reduce the plaque pathology, suggesting that Aβ42 and Aβ40 also interact in vivo. Here we address the question of whether Aβ42 and Aβ40 interact with each other in the formation of oligomers using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. When the Aβ42 oligomers were formed using only spin-labeled Aβ42, the dipolar interaction between spin labels that are within 20 Å range broadened the EPR spectrum and reduced its amplitude. Oligomers formed with a mixture of spin-labeled Aβ42 and wild-type Aβ42 gave an EPR spectrum with higher amplitude due to weakened spin-spin interactions, suggesting molecular mixing of labeled and wild-type Aβ42. When spin-labeled Aβ42 and wild-type Aβ40 were mixed to form oligomers, the resulting EPR spectrum also showed reduced amplitude, suggesting that wild-type Aβ40 can also form oligomers with spin-labeled Aβ42. Therefore, our results suggest that Aβ42 and Aβ40 form mixed oligomers with direct molecular interactions. Our results point to the importance of investigating Aβ42-Aβ40 interactions in the brain for a complete understanding of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: amyloid, protein aggregation, Alzheimer’s disease, oligomers

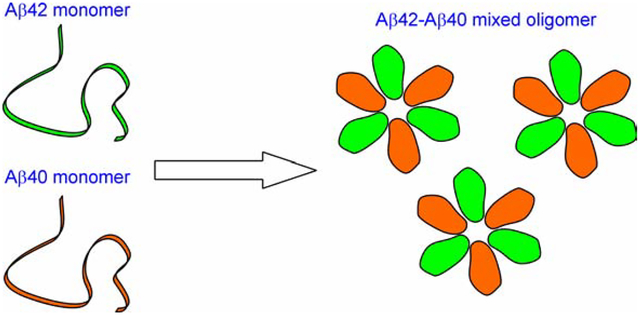

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Deposition of Aβ aggregates plays a central role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease [1]. Aβ is produced from the proteolytic digestion of amyloid precursor protein by β- and γ-secretases [2]. The cleavage by γ-secretase is not specific, generating a number of Aβ proteins with various C-terminal ends. The most abundant Aβ species is the 40-residue Aβ40, followed by the 42-residue Aβ42. Although Aβ40 is several fold more abundant than Aβ42 in the brain [3–5], the main Aβ species in amyloid plaques is Aβ42 [6–8]. Several studies have shown that Aβ40 is present only in a subset of amyloid plaques [6,7,9], suggesting that Aβ42 aggregation may precede Aβ40 aggregation. Overexpression of Aβ40 in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease reduced the plaque pathology, suggesting a protective role for Aβ40 [10]. Therefore, studying interactions between Aβ42 and Aβ40 may provide mechanistic insight into the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and facilitate development of therapeutic interventions.

In vitro studies show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 interact at molecular level and affect each other’s aggregation. Surface plasmon resonance experiments showed direct interaction between Aβ40 and Aβ42 monomers [11]. NMR studies suggest that Aβ40 inhibits the aggregation of Aβ42 by binding to existing Aβ42 aggregates [12]. Jan et al. [13] showed increasing Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio reduced fibril formation and led to reduced toxicity. The fibrils of Aβ40 can seed the aggregation of Aβ42, and vice versa [14,15]. Our previous EPR studies show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 form interlaced amyloid fibrils [16]. A recent NMR study found that mixing of Aβ40 and Aβ42 led to the formation of a fibril whose structure is different from that of either pure Aβ40 or Aβ42 fibrils [17].

In addition to amyloid fibrils, Aβ aggregation also generates soluble oligomers, which are considered to be the more toxic and pathogenic form of Aβ aggregates [18]. Using an environment-sensitive fluorophore, Frost et al. [19] showed that Aβ40 and Aβ42 formed mixed pre-fibrillar aggregates. Iljina et al. [20] used single-molecule two-color coincidence detection to show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 co-oligomerize at physiologically relevant concentrations. More recently, Baldassarre [21] used Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 form mixed oligomers with randomly distributed Aβ42 and Aβ40 strands in the β-sheet. In all three studies, the oligomers were prepared by lowering the sample pH from basic to neutral. Specific oligomer protocols such as Aβ-derived diffusible ligands [22] and globulomers [23] are used to prepare oligomers for in vitro [24,25] and in vivo studies [18,26,27]. But no studies have been reported on Aβ40-Aβ42 interactions in these specific oligomer preparations.

In this work, we aim to study whether Aβ42 and Aβ40 directly interact with each other in Aβ globulomers, which are prepared in the presence of low concentrations of SDS [23,28]. The continuous-wave EPR spectrum is sensitive to spin-spin interactions when spin labels are within a range of approximately 20 Å. In a previous study of Aβ42 globulomers [29], we showed that the spin labels introduced at the same residue position are approximately 10–15 Å apart, consistent with an antiparallel β-sheet arrangement in globulomers. The EPR spectra of Aβ42 oligomers formed by 100% spin-labeled Aβ42 are broadened by spin-spin interactions, which are diminished in globulomers formed by a mixture of spin-labeled and wild-type Aβ42. This provides us an approach to study the interactions between Aβ42 and Aβ40 in the globulomers (Figure 1). Globulomers prepared with a mixture of spin-labeled Aβ42 and wild-type Aβ40 will show reduced spin-spin interactions if Aβ42 and Aβ40 interact at molecular level, and unchanged spin-spin interactions if Aβ42 and Aβ40 do not interact at molecular level.

Figure 1. Rationale of study design.

Due to spin-spin interactions, Aβ42 oligomers formed by only spin-labeled Aβ42 have an EPR spectrum with broadened lines and reduced amplitude. When the oligomers are formed by spin-labeled and wild-type Aβ42, the spin-spin interaction is weakened, resulting in an EPR spectrum of sharper lines and higher amplitude. The EPR spectrum of oligomers formed by spin-labeled Aβ42 and wild-type Aβ40 would provide information on whether Aβ42 and Aβ40 interact at molecular level in these oligomers. Dashed lines are drawn to aid for comparison.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Preparation of wild-type Aβ proteins.

Detailed procedure of Aβ preparation has been described previously [29]. Briefly, Aβ40 and Aβ42 proteins were expressed in E. coli C41(DE3) cells (Lucigen) using a fusion protein construct, GroES-ubiquitin-Aβ [30]. Following purification using a nickel column under denaturing conditions, the fusion protein partners were cleaved off using a deubiquitylating enzyme, Usp2-cc [31]. This leads to the purification of full-length Aβ40 or Aβ42 proteins without any extra residues. Finally, Aβ proteins were buffer exchanged to 30 mM ammonium acetate, pH 10, lyophilized, and stored at −80°C. Throughout the purification process, Aβ proteins were kept in buffers of pH 10 and never exposed to acidic conditions. The identity of the protein was confirmed using mass spectrometry.

Preparation of spin-labeled Aβ42.

A cysteine mutant of Aβ42, G37C, was constructed using site-directed mutagenesis approach with QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent). Protein purification was performed similarly as wild-type Aβ. For spin labeling, Aβ42 G37C protein was first treated with 10 mM TCEP at room temperature for 20 min to break any disulfide bonds. Then the protein was buffer exchanged to labeling buffer (20 mM MOPS, 7 M guanidine hydrochloride, pH 6.8). Spin labeling reagent MTSSL, 1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl methanethiosulfonate (Adipogen), was added at 10-fold molar excess and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Then the labeling mixture was buffered exchanged to 30 mM ammonium acetate (pH 10), lyophilized, and stored at −80°C. The extent of labeling was evaluated with mass spectrometry. Only samples with labeling efficiency of >95% were used in the subsequent experiments. The spin label side chain is named R1 and the spin-labeled Aβ42 mutant is thus named G37R1.

Preparation of Aβ globulomers.

Lyophilized powder of wild-type Aβ40, wild-type Aβ42, and spin-labeled Aβ42 (G37R1) was first dissolved in 100% 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) at 1 mM, bath-sonicated for 5 min, and then incubated at room temperature for 30 min. HFIP was allowed to evaporate overnight in a fume hood. HFIP treated samples were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 5 mM and bath-sonicated for 5 min. The Aβ concentration was determined using a fluorescamine method [32]. We prepared four samples of Aβ globulomers. Sample 1 is 100% spin-labeled Aβ42. Sample 2 is a mixture 25% spin-labeled and 75% wild-type Aβ42. Sample 3 is a mixture of 25% spin-labeled Aβ42, 25% wild-type Aβ42, and 50% wild-type Aβ40. Sample 4 is a mixture of 25% spin-labeled Aβ42 and 75% wild-type Aβ40. To prepare globulomers, these four Aβ samples in DMSO were diluted using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (20 mM phosphate, 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) to 400 μM containing 0.2% (final concentration) SDS. After incubation for 6 h at 37°C, these four Aβ samples were further diluted with 3 volumes of deionized water to a final concentration of 100 μM and incubated for another 18 h at 37°C. For collecting the globulomers, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min to remove insoluble aggregates, and the supernatant was concentrated using an ultrafiltration filter with 30-kD molecular mass cut-off. Samples in the retentate contained the globulomers.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Aβ globulomers (5 μL) was placed on glow-discharged copper grids covered with 400-mesh Formvar/carbon film (Ted Pella). Then the samples were negatively stained using 2% uranyl acetate and examined under a JEOL JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope at 80 kV.

EPR spectroscopy.

Aβ globulomer samples were loaded into glass capillaries (VitroCom) sealed at one end. A Bruker EMX EPR spectrometer equipped with the SR4102ST cavity was used for X-band continuous-wave EPR measurements at room temperature. A microwave power of 20 mW and a modulation frequency of 100 kHz were used. Modulation amplitude was optimized for each individual sample. Scan width was 200 G. All EPR spectra were normalized to the same number of spins.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To investigate whether Aβ42 and Aβ40 form mixed oligomers with molecular interactions, we took advantage of the dipolar interaction between spin labels when they are in a range of approximately 20 Å. The dipolar interaction broadens the EPR spectrum. As shown in Figure 1, when Aβ42 globulomers are prepared with 100% spin-labeled Aβ42, the resulting EPR spectrum is broader and has lower amplitude than globulomers prepared with a mixture of spin-labeled and wild-type Aβ42. This is because interdigitation between spin-labeled and wild-type Aβ42 in the oligomer increases the distance between spin labels, and thus reduces the dipolar spin-spin interaction. If Aβ40 and Aβ42 interact with each other at molecular level, then a mixture of spin-labeled Aβ42 and wild-type Aβ40 will lead to a similar level of reduction in the dipolar interaction between spin-labeled Aβ42.

Using spin-labeled Aβ42, G37R1, where R1 represents the spin label, wild-type Aβ42 and Aβ40, we prepared four globulomer samples with different ratios of the three Aβ proteins. The first sample is prepared with 100% spin-labeled Aβ42. Our previous studies show that the spin labels at position 37 are approximately 12 Å apart in the globulomer [29]. This sample gives strong dipolar interaction between spin labels. The second sample is a mixture of 25% spin-labeled Aβ42 and 75% wild-type Aβ42. This sample provides a control for reduced dipolar interaction. The third sample is a mixture of 25% spin-labeled Aβ42, 25% wild-type Aβ42, and 50% wild-type Aβ40. If Aβ40 does not form molecular interactions with Aβ42, we will observe a reduction of dipolar interaction but less than the mixture of 25% labeled and 75% wild-type Aβ42 sample. If Aβ40 interacts with Aβ42 in the oligomers, then this sample will give an EPR spectrum that is similar to the 75% wild-type Aβ42 sample. The fourth sample is a mixture of 25% spin-labeled Aβ42 and 75% wild-type Aβ40. In the absence of Aβ40-Aβ42 interaction, this sample will give an EPR spectrum that is the same as the 100% spin-labeled sample. In the presence of molecular interactions between Aβ40 and Aβ42, this sample will resemble the mixture of 25% labeled and 75% wild-type Aβ42 sample.

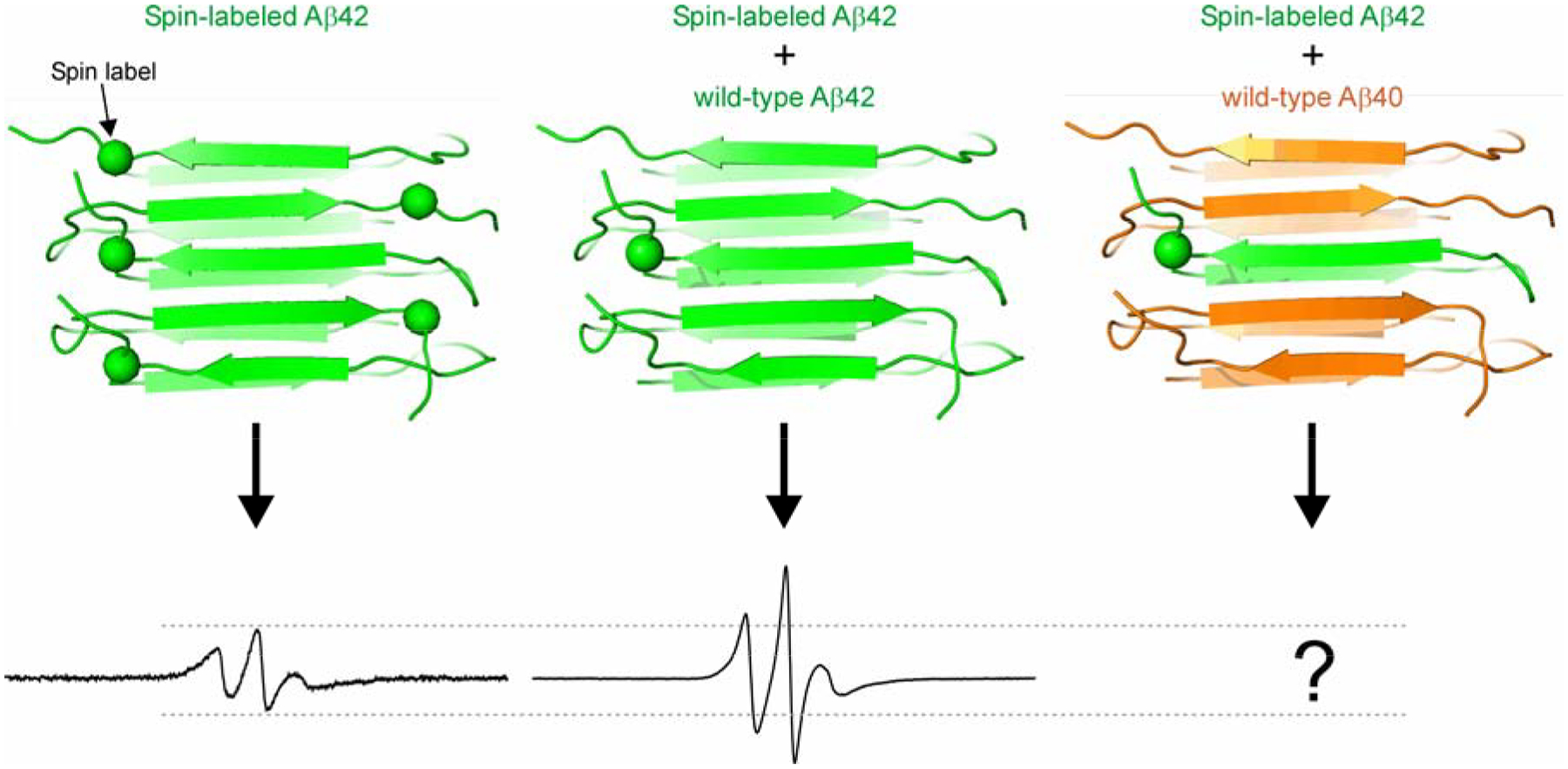

We examined the morphology of the four globulomer preparations using transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2). In addition to stand-alone oligomers (open arrowheads in Figure 2), we found that the Aβ globulomers have strong tendency to bind to each other, forming elongated and networked structures. Importantly, the four samples show similar morphology under electron microscope, suggesting that mixing of spin-labeled Aβ42 with either wild-type Aβ42 or Aβ40 had little effect on the globulomer morphology.

Figure 2. Transmission electron micrographs of Aβ globulomers prepared with different mixtures of spin-labeled and wild-type Aβ proteins.

Some stand-alone globular oligomers are present (open arrowheads), but most of the oligomers stick together to form elongated and networked structures. Overall, oligomers prepared from different mixtures of spin-labeled Aβ42, G37R1 (where R1 represents the spin label), with either wild-type Aβ42 or Aβ40 show similar morphology.

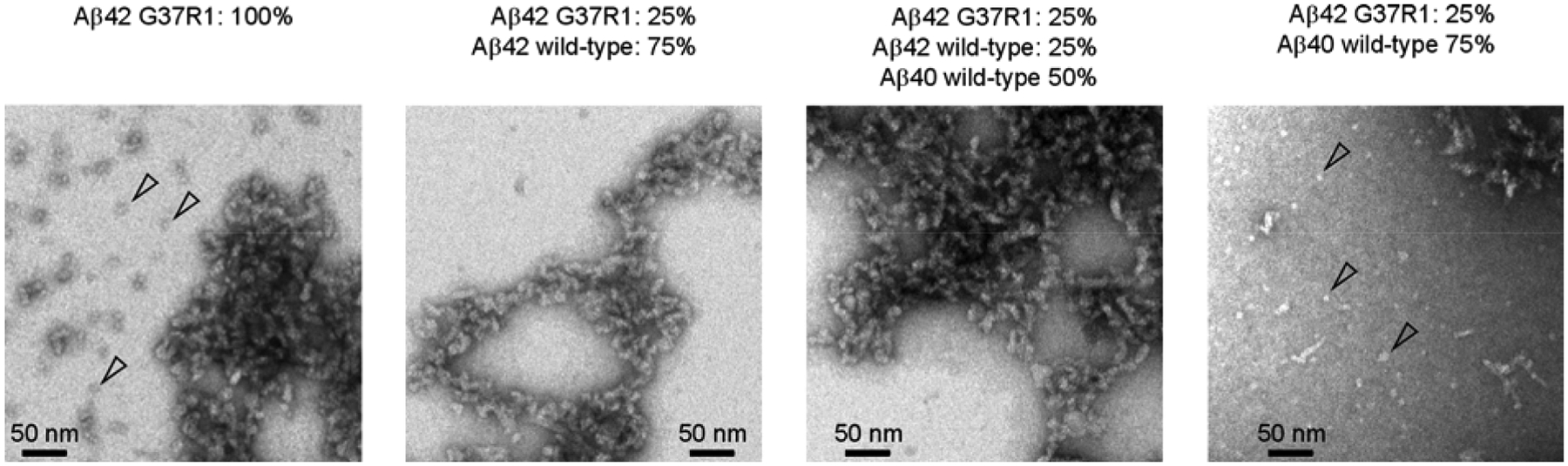

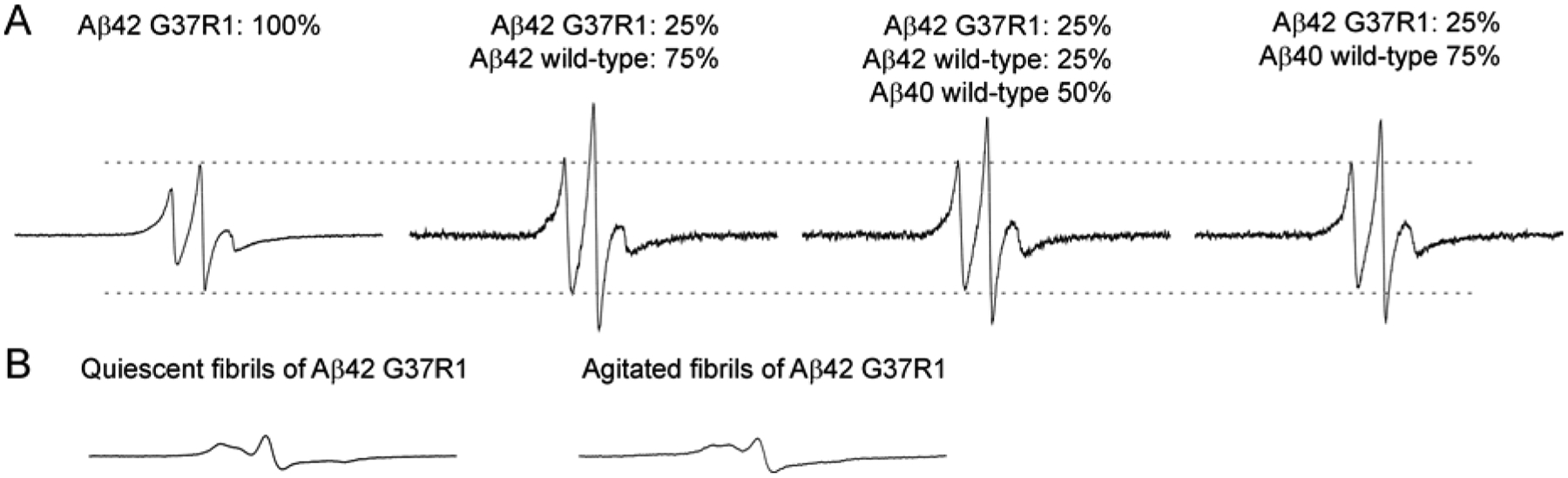

Next we performed EPR measurements on these four globulomer samples. As shown in Figure 3A, globulomers of 100% spin-labeled Aβ42, G37R1, show dipolar-broadened spectrum with smaller amplitude than the EPR spectrum of mixed globulomers of 25% labeled and 75% wild-type Aβ42. When globulomers are prepared with Aβ42 and Aβ40, either in a mixture of 25% spin-labeled Aβ42, 25% wild-type Aβ42, and 50% wild-type Aβ40, or a mixture of 25% spin-labeled Aβ42 and 75% wild-type Aβ40, the resulting EPR spectra are extremely similar to the mixture of 25% labeled Aβ42 and 75% wild-type Aβ42, suggesting that Aβ40 can substitute Aβ42 in forming mixed globulomers.

Figure 3. EPR spectra of Aβ globulomers and fibrils.

(A) EPR spectra of Aβ globulomers prepared with different mixtures of spin-labeled and wild-type Aβ proteins. R1 represents the spin label. Note that the EPR spectra of oligomers prepared with a mixture of spin-labeled Aβ42 and wild-type Aβ40 are very similar to those of oligomers prepared with a mixture of spin-labeled Aβ42 and wild-type Aβ42, suggesting Aβ42 and Aβ40 are interchangeable in the formation of Aβ globulomers. (B) EPR spectra of Aβ fibrils prepared with 100% spin-labeled Aβ42. Note that the EPR spectra of Aβ fibrils are dramatically different from those of oligomers, suggesting different underlying structures. Dashed lines are drawn to aid for comparison. Scan width for all EPR spectra is 200 G.

Although we observed abundant elongated and networked structures formed by Aβ globulomers, the EPR spectra consist of sharp lines, suggesting highly mobile structure in the oligomers (Figure 3A). These spectral features are distinct from the EPR spectra of amyloid fibrils formed by the same spin-labeled Aβ42 mutant (Figure 3B). In the fibrils, the EPR spectral lines are much broader, resulting in greatly reduced spectral amplitude. Another characteristic of the fibril spectrum is that the three EPR resonance lines collapse toward the center line as a result of the spin exchange interaction in the parallel in-register β-sheet structure of Aβ fibrils [33,34]. Therefore, even though the Aβ globulomers have a strong tendency to bind to each other, the structures remain unchanged and are very different from the structures in fibrils.

The findings that Aβ42 and Aβ40 have molecular interactions in globulomers are consistent with previous reports that Aβ42 and Aβ40 form mixed prefibrillar aggregates. Previously, Barth and coworkers [21] used Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 form mixed oligomers with randomly distributed Aβ42 and Aβ40 strands in the β-sheet. In their study, they prepared Aβ oligomers by rapidly changing the solution pH from >11 to 7.4. In addition to showing the mixed nature of Aβ oligomers formed by Aβ42 and Aβ40, the infrared spectroscopy also provided evidence for the antiparallel signature of β-sheets. Another study by Frost et al. [19] used an environment-sensitive fluorescent label to show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 formed mixed prefibrillar oligomers when the buffer pH was adjusted from 10 to 7. Iljina et al. [20] used two-color coincidence detection method to show that Aβ42 and Aβ40 formed mixed oligomers at physiologically relevant concentrations. What distinguish this work from previous ones is that we prepared oligomers using a well-established protocol for globulomers [23,28]. A similar protocol was used by Paravastu and coworkers to prepare “150 kDa oligomers”, which were shown to consist of both out-of-register parallel β-sheets and antiparallel β-sheets in NMR studies [24]. EPR data in our previous work are consistent with antiparallel β-sheet structure [29]. Together with the reports on mixed Aβ42-Aβ40 amyloid fibrils [16,17], the evidence is strong for molecular interactions between Aβ42 and Aβ40 in the aggregation process and the aggregated products.

Our findings also have in vivo implications. The composition of amyloid fibrils in the brain has been extensively studied. Aβ42 has been found to be the major component of parenchymal plaques [6–8], even though Aβ40 is several-fold more abundant than Aβ42 in the brain [3–5]. Several studies found that soluble Aβ aggregates isolated from brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients contains both Aβ42 and Aβ40 [35–37]. Wildburger et al. [36] used mass spectrometry to study the Aβ isoforms in soluble Aβ oligomers and found that both Aβ42 and Aβ40 are present in the soluble aggregates, with Aβ42 clearly more abundant than Aβ40. Using end-specific antibodies, Yang et al. [37] also found that the high molecular weight Aβ oligomers consist of both Aβ42 and Aβ40. Mass spectrometry revealed the presence of heterogeneous Aβ42-Aβ40 dimers in the brain extracts, suggesting that Aβ42 and Aβ40 indeed form mixed oligomers in the brain [35]. In mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ40 has been shown to have strong anti-amyloid effect [10]. Using BRI-Aβ40 construct to overexpress Aβ40, Kim et al. [10] showed that two fold increase of Aβ40 levels in Tg2576 mice reduced Aβ deposition by ~80% at 11 months and ~50% at 20 months. Selective overexpression of Aβ42 had the exact opposite effect of plaque pathology [38]. There have yet to be studies on the correlation between Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in oligomers and the severity of Alzheimer’s symptom. Such information would provide invaluable insights into the role of Aβ42-Aβ40 interaction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and lay foundations for new avenues of therapeutic intervention.

Aβ aggregation underlies the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Aβ has two main isoforms: Aβ42 and Aβ40.

Aβ42 is the main component in amyloid plaques, but Aβ40 is more abundant.

EPR studies show Aβ42 and Aβ40 interact with each other in oligomers.

Future studies should have a focus on Aβ composition of in vivo oligomers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank So Hui Won and Tiffany Y. Lin for the preparation of Aβ proteins. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (Grant number R01AG050687)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Amyloid β-protein and beyond: the path forward in Alzheimer’s disease, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 61 (2020) 116–124. 10.1016/j.conb.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].De Strooper B, Vassar R, Golde T, The secretases: enzymes with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer disease, Nat Rev Neurol. 6 (2010) 99–107. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Huang Y, Potter R, Sigurdson W, Santacruz A, Shih S, Ju Y-E, Kasten T, Morris JC, Mintun M, Duntley S, Bateman RJ, Effects of age and amyloid deposition on Aβ dynamics in the human central nervous system, Arch. Neurol 69 (2012) 51–58. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mehta PD, Pirttilä T, Mehta SP, Sersen EA, Aisen PS, Wisniewski HM, Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta proteins 1–40 and 1–42 in Alzheimer disease, Arch. Neurol 57 (2000) 100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Portelius E, Andreasson U, Ringman JM, Buerger K, Daborg J, Buchhave P, Hansson O, Harmsen A, Gustavsson MK, Hanse E, Galasko D, Hampel H, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Distinct cerebrospinal fluid amyloid β peptide signatures in sporadic and PSEN1 A431E-associated familial Alzheimer’s disease, Mol Neurodegener. 5 (2010) 2 10.1186/1750-1326-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y, Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: Evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43), Neuron. 13 (1994) 45–53. 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mak K, Yang F, Vinters HV, Frautschy SA, Cole GM, Polyclonals to β-amyloid(1–42) identify most plaque and vascular deposits in Alzheimer cortex, but not striatum, Brain Res. 667 (1994) 138–142. 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Miller DL, Papayannopoulos IA, Styles J, Bobin SA, Lin YY, Biemann K, Iqbal K, Peptide compositions of the cerebrovascular and senile plaque core amyloid deposits of Alzheimer′s disease, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 301 (1993) 41–52. 10.1006/abbi.1993.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Younkin LH, Suzuki N, Younkin SG, Amyloid β protein (Aβ) in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at Aβ40 or Aβ42(43), J. Biol. Chem 270 (1995) 7013–7016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim J, Onstead L, Randle S, Price R, Smithson L, Zwizinski C, Dickson DW, Golde T, McGowan E, Aβ40 inhibits amyloid deposition in vivo, J. Neurosci 27 (2007) 627–633. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4849-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pauwels K, Williams TL, Morris KL, Jonckheere W, Vandersteen A, Kelly G, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Pastore A, Serpell LC, Broersen K, Structural basis for increased toxicity of pathological Aβ42:Aβ40 ratios in Alzheimer disease, J. Biol. Chem 287 (2012) 5650–5660. 10.1074/jbc.M111.264473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yan Y, Wang C, Aβ40 protects non-toxic Aβ42 monomer from aggregation, J. Mol. Biol 369 (2007) 909–916. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jan A, Gokce O, Luthi-Carter R, Lashuel HA, The ratio of monomeric to aggregated forms of Aβ40 and Aβ42 is an important determinant of amyloid-β aggregation, fibrillogenesis, and toxicity, J. Biol. Chem 283 (2008) 28176–28189. 10.1074/jbc.M803159200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hasegawa K, Yamaguchi I, Omata S, Gejyo F, Naiki H, Interaction between Aβ(1–42) and Aβ(1–40) in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibril formation in vitro, Biochemistry. 38 (1999) 15514–15521. 10.1021/bi991161m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tran J, Chang D, Hsu F, Wang H, Guo Z, Cross-seeding between Aβ40 and Aβ42 in Alzheimer’s disease, FEBS Lett. 591 (2017) 177–185. 10.1002/1873-3468.12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gu L, Guo Z, Alzheimer’s Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides form interlaced amyloid fibrils, J. Neurochem 126 (2013) 305–311. 10.1111/jnc.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cerofolini L, Ravera E, Bologna S, Wiglenda T, Böddrich A, Purfürst B, Benilova I, Korsak M, Gallo G, Rizzo D, Gonnelli L, Fragai M, De Strooper B, Wanker EE, Luchinat C, Mixing Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) peptides generates unique amyloid fibrils, Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 56 (2020) 8830–8833. 10.1039/d0cc02463e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cline EN, Bicca MA, Viola KL, Klein WL, The amyloid-β oligomer hypothesis: beginning of the third decade, J. Alzheimers Dis 64 (2018) S567–S610. 10.3233/JAD-179941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Frost D, Gorman PM, Yip CM, Chakrabartty A, Co-incorporation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 to form mixed pre-fibrillar aggregates, Eur. J. Biochem 270 (2003) 654–663. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Iljina M, Garcia GA, Dear AJ, Flint J, Narayan P, Michaels TCT, Dobson CM, Frenkel D, Knowles TPJ, Klenerman D, Quantitative analysis of co-oligomer formation by amyloid-beta peptide isoforms, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 28658 10.1038/srep28658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baldassarre M, Baronio CM, Morozova-Roche LA, Barth A, Amyloid β-peptides 1–40 and 1–42 form oligomers with mixed β-sheets, Chem. Sci 8 (2017) 8247–8254. 10.1039/C7SC01743J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL, Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 95 (1998) 6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Barghorn S, Nimmrich V, Striebinger A, Krantz C, Keller P, Janson B, Bahr M, Schmidt M, Bitner RS, Harlan J, Barlow E, Ebert U, Hillen H, Globular amyloid β-peptide1–42 oligomer − a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer’s disease, J. Neurochem 95 (2005) 834–847. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gao Y, Guo C, Watzlawik JO, Randolph PS, Lee EJ, Huang D, Stagg SM, Zhou H-X, Rosenberry TL, Paravastu AK, Out-of-register parallel β-sheets and antiparallel β-sheets coexist in 150 kDa oligomers formed by Amyloid-β(1–42), J. Mol. Biol (2020). 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yu L, Edalji R, Harlan JE, Holzman TF, Lopez AP, Labkovsky B, Hillen H, Barghorn S, Ebert U, Richardson PL, Miesbauer L, Solomon L, Bartley D, Walter K, Johnson RW, Hajduk PJ, Olejniczak ET, Structural Characterization of a Soluble Amyloid β-Peptide Oligomer, Biochemistry. 48 (2009) 1870–1877. 10.1021/bi802046n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Benilova I, Karran E, Strooper BD, The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes, Nat. Neurosci 15 (2012) 349–357. 10.1038/nn.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Thal DR, Walter J, Saido TC, Fändrich M, Neuropathology and biochemistry of Aβ and its aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease, Acta Neuropathol. 129 (2015) 167–182. 10.1007/s00401-014-1375-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ryan DA, Narrow WC, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ, An improved method for generating consistent soluble amyloid-beta oligomer preparations for in vitro neurotoxicity studies, J. Neurosci. Methods 190 (2010) 171–179. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gu L, Liu C, Guo Z, Structural insights into Aβ42 oligomers using site-directed spin labeling, J. Biol. Chem 288 (2013) 18673–18683. 10.1074/jbc.M113.457739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shahnawaz M, Thapa A, Park I-S, Stable activity of a deubiquitylating enzyme (Usp2-cc) in the presence of high concentrations of urea and its application to purify aggregation-prone peptides, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 359 (2007) 801–805. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Baker RT, Catanzariti A-M, Karunasekara Y, Soboleva TA, Sharwood R, Whitney S, Board PG, Using deubiquitylating enzymes as research tools, Meth. Enzymol 398 (2005) 540–554. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xue C, Lee YK, Tran J, Chang D, Guo Z, A mix-and-click method to measure amyloid-β concentration with sub-micromolar sensitivity, R. Soc. Open Sci 4 (2017) 170325 10.1098/rsos.170325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang H, Duo L, Hsu F, Xue C, Lee YK, Guo Z, Polymorphic Aβ42 fibrils adopt similar secondary structure but differ in cross-strand side chain stacking interactions within the same β-sheet, Sci Rep. 10 (2020) 5720 10.1038/s41598-020-62181-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Margittai M, Langen R, Fibrils with parallel in-register structure constitute a major class of amyloid fibrils: molecular insights from electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, Q. Rev. Biophys 41 (2008) 265–297. 10.1017/S0033583508004733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brinkmalm G, Hong W, Wang Z, Liu W, O’Malley TT, Sun X, Frosch MP, Selkoe DJ, Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Walsh DM, Identification of neurotoxic cross-linked amyloid-β dimers in the Alzheimer’s brain, Brain. 142 (2019) 1441–1457. 10.1093/brain/awz066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wildburger NC, Esparza TJ, LeDuc RD, Fellers RT, Thomas PM, Cairns NJ, Kelleher NL, Bateman RJ, Brody DL, Diversity of Amyloid-beta Proteoforms in the Alzheimer’s Disease Brain, Sci Rep. 7 (2017) 9520 10.1038/s41598-017-10422-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yang T, Li S, Xu H, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Large soluble oligomers of amyloid β-protein from Alzheimer brain are far less neuroactive than the smaller oligomers to which they dissociate, J. Neurosci 37 (2017) 152–163. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1698-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].McGowan E, Pickford F, Kim J, Onstead L, Eriksen J, Yu C, Skipper L, Murphy MP, Beard J, Das P, Jansen K, Delucia M, Lin W-L, Dolios G, Wang R, Eckman CB, Dickson DW, Hutton M, Hardy J, Golde T, Aβ42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice, Neuron. 47 (2005) 191–199. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]