Abstract

Mitochondrial ATP synthase plays a key role in inducing membrane curvature to establish cristae. In Apicomplexa causing diseases such as malaria and toxoplasmosis, an unusual cristae morphology has been observed, but its structural basis is unknown. Here, we report that the apicomplexan ATP synthase assembles into cyclic hexamers, essential to shape their distinct cristae. Cryo-EM was used to determine the structure of the hexamer, which is held together by interactions between parasite-specific subunits in the lumenal region. Overall, we identified 17 apicomplexan-specific subunits, and a minimal and nuclear-encoded subunit-a. The hexamer consists of three dimers with an extensive dimer interface that includes bound cardiolipins and the inhibitor IF1. Cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging revealed that hexamers arrange into ~20-megadalton pentagonal pyramids in the curved apical membrane regions. Knockout of the linker protein ATPTG11 resulted in the loss of pentagonal pyramids with concomitant aberrantly shaped cristae. Together, this demonstrates that the unique macromolecular arrangement is critical for the maintenance of cristae morphology in Apicomplexa.

Subject terms: Mitochondria, Molecular evolution, Cryoelectron microscopy, Cryoelectron tomography

Structural and functional analysis of mitochondria from the human parasite Toxoplasma gondii reveals that its ATP synthase assembles into cyclic hexamers, arranged together in a form of pentagonal pyramids required for maintenance of cristae morphology in Apicomplexa.

Introduction

F-type ATP synthases are energy-converting membrane protein complexes that synthesize adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from ADP and inorganic phosphate. These universal enzymes function by using the energy stored in an electrochemical potential across the bioenergetic membrane by rotary catalysis1,2. The soluble F1 subcomplex and membrane-bound Fo subcomplex together form the F1Fo ATP synthase monomer, which is found in bacteria and chloroplasts3,4. In mitochondria, F1Fo ATP synthase resides in the crista membrane where it is known to form dimers, which can further assemble into rows critical for inducing the membrane curvature and maintaining membrane potential and morphology5–10.

The main driving force for the synthesis of ATP in mitochondria is the membrane potential11, which has been shown to be higher in the cristae lumen than in the adjacent intermembrane space12. Cristae shaping has been shown to depend on the assembly of ATP synthase dimers into dimer rows, which is the basis for energy conversion in all mitochondria studied to date13. However, the molecular interactions that convey the membrane-shaping properties of the oligomeric ATP synthase are poorly understood. Furthermore, structural data has shown that cristae morphology varies between eukaryotic lineages13.

The infectious apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii14 is commonly used as a model organism for the malaria-causing agent Plasmodium spp15. These parasites have a unique bulbous cristae morphology, which differs substantially from the lamellar cristae of their mammalian hosts16,17. The underlying mechanism for the bulbous cristae is unknown. Loss of ATP synthase is accompanied by parasite death and defects in cristae abundance in the T. gondii stage responsible for acute toxoplasmosis18, and results in the death of the Plasmodium mosquito form responsible for malaria spread19. Here, we investigate the mechanism for the generation of the unique cristae in the Apicomplexa, using a combination of single-particle cryo-EM, cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging. We first report cristae-embedded ATP synthase hexamers arranged in pentagonal pyramids in the wild type, then identify a key subunit for the assembly, and finally characterise mutant cells with a generated knockout of this subunit.

Results

Structure of the hexameric ATP synthase and its herein identified elements

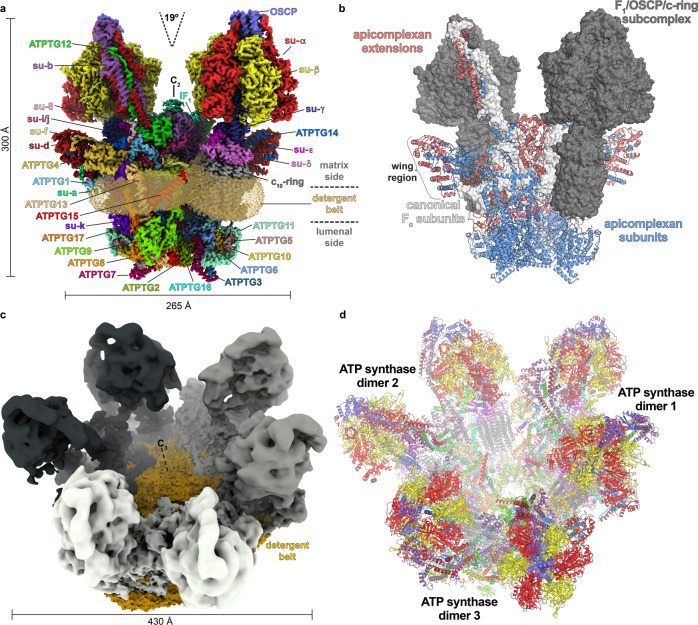

A large-scale preparation of T. gondii tachyzoite mitochondria and subsequent mild solubilisation with digitonin resulted in the isolation of intact ATP synthase complexes, which we identified as native hexamers. We then performed solubilisation with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (β–DDM) that resulted in dissociation of the hexamers into dimers. Both oligomeric forms were subjected to cryo-EM structure determination (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Masked refinements of the ATP synthase dimer resulted in maps of the membrane region, the OSCP/F1/c-ring complex, the rotor and the peripheral stalk, ranging in resolution from 2.8 to 3.5 Å (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 3), thus allowing de novo modelling of the respective regions. Refinement into a 2.9-Å resolution consensus map allowed model construction of the entire ATP synthase dimer (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Table 1). The 1.85-MDa complex consists of 32 different subunits, of which only 15 are canonical with structural equivalents in other phyla. Homolog searches of 17 noncanonical subunits revealed them to be largely conserved in mitochondriate Apicomplexa including Plasmodium parasites, and in the related phyla of chromerids and perkinsozoa, suggesting that the herein described architecture is likely representative of myzozoans (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, following a species-specific nomenclature established in protozoan ATP synthases20–22, we term the 17 apicomplexan-conserved T. gondii subunits ATPTG1-17 (TG for T. gondii), with ATPTG1, ATPTG7, and ATPTG16 identified directly from the cryo-EM map (Supplementary Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1. Overall architecture of T. gondii ATP synthase dimer and hexamer.

a The composite cryo-EM map of the dimer highlights a small dimer angle and large lumenal region. b The atomic model of the dimer with highlighted apicomplexan-specific structural components responsible for the specific mode of dimerization. c Cryo-EM map of the hexamer showing an assembly as trimer of dimers. d Atomic model of the hexamer with individually coloured subunits.

The apicomplexan-conserved subunits and extensions of the canonical subunits constitute a membrane-embedded Fo subcomplex, which ties the two F1/c-ring subcomplexes together at the angle of 19° (Fig. 1a, b). This is in stark contrast to ~100° found in the yeast and mammalian ATP synthase dimers23,24, suggesting the narrow-angle parasite dimer induces substantially less membrane curvature. The enlarged T. gondii Fo subcomplex differs markedly in its overall architecture from other ATP synthase structures. It displays distinct structural features including a peripheral matrix-exposed part that we term ‘wing’ region and a 360-kDa lumenal region (Fig. 1b). The Fo periphery contains several compact folds, including three coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain (CHCHD) containing proteins ATPTG7-9; a thioredoxin-like fold in ATPTG4; and ubiquitin-like fold in subunit-k (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

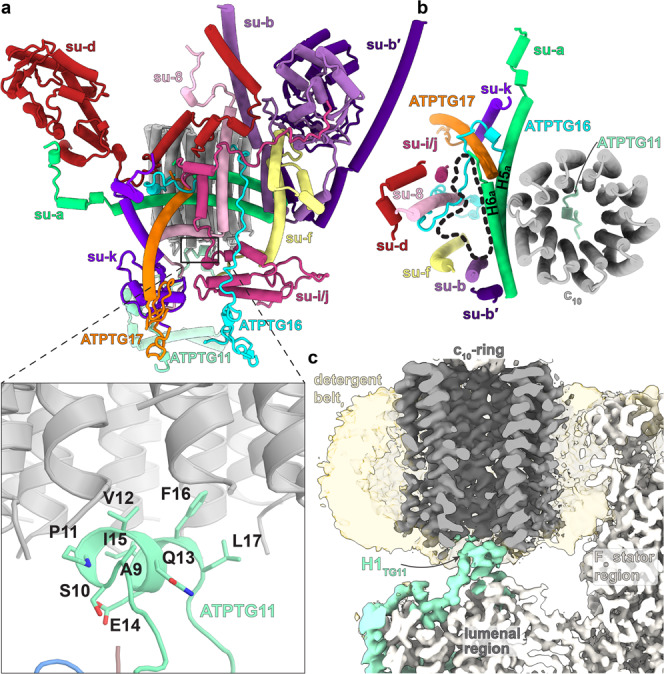

The apicomplexan-conserved Fo-subunit ATPTG11 extends from the lumenal region and plugs the central cavity of the c-ring. This is mediated by the short N-terminal amphipathic helix of ATPTG11 (Ala9-Leu17), which is sequence-conserved in Apicomplexa (Fig. 2a, b). The interface is located on the border of the detergent belt and dominated by hydrophobic residues of ATPTG11 pointing towards the inside of the c-ring, which is unlikely to inhibit the rotation of the rotor (Fig. 2a, c). Protein density on the inside of the c-ring, as suggested for the porcine complex24, was not observed.

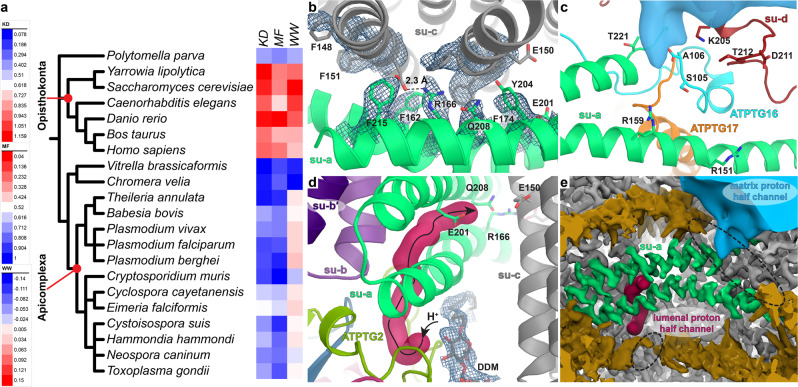

Fig. 2. Conserved and apicomplexan-specific Fo components of hexameric ATP synthase.

a The canonical Fo subunits b, d, f, i/j, k, and 8 contain apicomplexan-specific extensions contributing to a large Fo. Subunit-a contains only the conserved H5-6a, and ATPTG16, ATPTG17 partially replace the missing H1-4a. Inset shows N-terminal helix of ATPTG11 forming a parasite-specific rotor-stator interface with the lumenal side of the c-ring. b Top view of rotor-stator interface. The absence of H1-4a separates subunit-a from several canonical Fo-subunits. Resulting lipid-filled Fo void outlined (black dash). c Cross section through the Fo region of the map. ATPTG11 extends from the lumenal region to plug the c-ring through interactions with H1TG11.

Masked refinement of the hexamer membrane region resulted in a 4.8-Å resolution map (Supplementary Fig. 2). Refining three copies of the dimer model into the hexamer map resulted in a good fit and showed that it forms a cyclic trimer of dimers. No additional subunits or substantial conformational changes of the dimer units were found in the hexameric assembly (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Movie 1). The C2 symmetry axis through the dimer is tilted 22° with respect to the C3 axis in the hexamer, thereby bringing into proximity the lumenal regions, which extend 80 Å from the membrane.

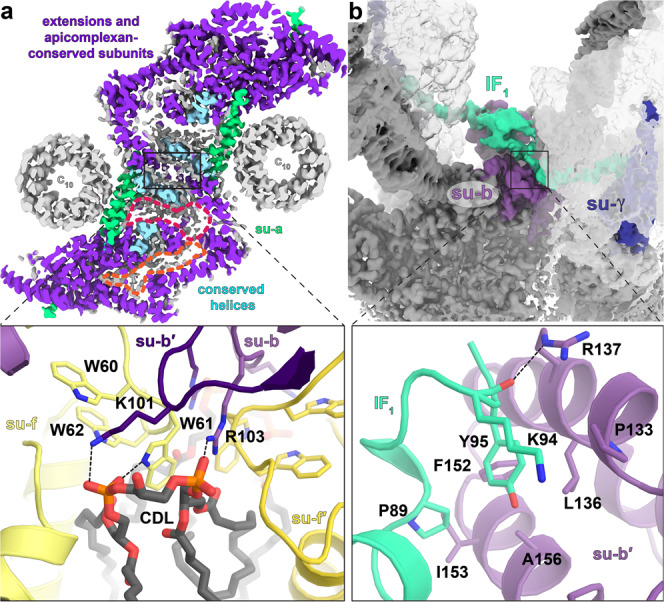

Parasite-specific subunits form a dimer interface that includes IF1 and bound cardiolipins

The structure of the T. gondii ATP synthase reveals that the unusual architecture of the dimer is generated by the peripheral stalks that are laterally offset, extending away from the central dimer axis (Fig. 1a, b). This architecture does not allow the formation of the conventional dimerization interface of type-I ATP synthases found in animals and yeast (Supplementary Fig. 5i, j), in which peripheral stalks extend along the dimer long axis13. We therefore examined the dimerization interface, which is formed by the apicomplexan subunits and extensions of the canonical Fo subunits. Those elements involve eleven proteins from each monomer that contribute more than 7000 Å2 of buried surface area, making the interface substantially larger than in mammalian, yeast and algal ATP synthase structures (Supplementary Fig. 5c–j).

The dimerization interface in the membrane and lumenal regions is governed by homotypic interactions between symmetry-related subunits, most of which extend deep into both monomers. Subunit-b contains two transmembrane helices, each binds one of the symmetry-related subunit-a copies, which are therefore linked by four transmembrane helices (Fig. 2a, b). In addition, two cardiolipins are found on the matrix side, forming specific protein-lipid interactions bridging the two copies of subunit-b and subunit-f (Fig. 3a). This cardiolipin pair is sequestered in the Fo subcomplex with no apparent path to the bulk membrane, suggesting a structural role. An additional 15 cardiolipins and 12 other phospholipids were found to mediate a network of interactions throughout the membrane region (Supplementary Fig. 6a). These native lipids are primarily bound in two vestibules within the Fo subcomplex (Fig. 3a) with the lipid head groups mediating charged interactions between numerous subunits (Supplementary Fig. 6b–e), which indicates a contribution to the stability of the complex.

Fig. 3. Parasite-specific subunits and resolved lipids at the dimer interface.

a Fo map cross-section showing apicomplexa-specific (purple) and conserved (light blue) subunits, as well as lipid vestibules (red, orange). The apicomplexa-specific subunits scaffold the Fo architecture. Close-up inset shows protein-cardiolipin (CDL) contact at dimer interface with subunits b and f interacting via a tightly bound cardiolipin. b IF1 dimer (green density) binds to Fo (dark grey density) and F1 of both monomers (transparent grey), linking them together. Close-up inset shows IF1 interactions with subunit-b (violet).

The inhibitor protein of ATPase activity IF1 is bound to subunit-b, contributing to the Fo dimer interface with its C-terminal helix extending from F1 to interact with subunit-b’ of the neighbouring monomer (Fig. 3b). IF1 in our structure is bound exclusively to the α/β-interface facing the dimer interface (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 7a–d, f), thereby locking it in the ADP-bound state (βDP). The N-terminal IF1 region that contacts the central stalk in the bovine complex25 is absent in our structure (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Because central stalk rotation and conformational changes in the catalytic sites of F1 are interdependent, the sterically restrictive IF1 binding in T. gondii to only one of the three catalytic sites results in the trapping of the ATP synthase in a single rotational state in both the dimer and hexamer. In our cryo-EM maps, IF1 is contiguous with Fo-associated density extending to the C2-symmetry axis, thus linking the two F1 monomers (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 7f). We assign it to the unmodeled C-terminal region of IF1, which has previously been characterised as a homo-oligomerisation domain in mammals26. This bridging of two F1 monomers is intra-dimeric, which is different from the mammalian ATP synthase tetramer, where bridging occurs between the two neighbouring dimers24,27 (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f).

Evolutionary and functional aspects of a minimal and nuclear-encoded subunit-a

We assigned subunit-a by locating topologically conserved transmembrane helices of the canonical subunits b, d, f, i/j, k, and 8 (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 8d). Based on the sequence identified directly from the cryo-EM map, we found that T. gondii subunit-a is encoded in the nucleus, and not in mitochondria as in most other organisms. Thus, in T. gondii, all ATP synthase subunits are nuclear-encoded (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, unlike in the canonical six-helix (H1-6a) fold, which is conserved in bacteria, chloroplasts and other mitochondria4,28–30, the subunit-a in T. gondii lacks H1-4a, and only the horizontal H5a and H6a are found. They interact with the c-ring at the rotor-stator interface (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). This is the smallest subunit-a structure reported to date.

The unmodelled sequence that would make up the canonical transmembrane H1-4a, corresponds to a mitochondrial targeting sequence with a predicted cleavage site located N-terminally of H5a, thereby causing the truncation (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Thus, compared to its mitochondria-encoded homologs, T. gondii subunit-a displays a reduced overall hydrophobicity, which we found to be conserved in Apicomplexa (Fig. 4a). A similar observation for different mitochondrial membrane proteins has been proposed to enable mitochondrial protein targeting following gene transfer to the nucleus31–33.

Fig. 4. The minimal subunit-a is parasite-conserved and forms a salt bridge at the rotor-stator interface.

a Heat map indicating the average hydrophobicity of subunit-a in divergent organisms, calculated as the grand average of hydropathy (KD)84 or according to the Moon-Fleming (MF)85 or Wimley-White (WW)86 hydrophobicity scales. The nuclear-encoded subunit-a of apicomplexan parasites, as well as the related chromerid alveolates C. velia and V. brassicaformis show a reduced hydrophobicity compared to the mitochondria-encoded subunit-a homologs of animals and fungi. Reduced hydrophobicity is also found in subunit-a of the green alga P. parva, which is also nuclear encoded87 and lacks TM helix 1. b Top view of the subunit-a/c interfaces. The central arginine/glutamate pair is within interaction distance and enclosed by six aromatic residues. c Close-up view of the matrix half-channel (blue) with hydrophilic residues of subunits a, d and the C-terminus of ATPTG16 indicated. d Lumenal half-channel (burgundy) with proposed proton path to c-ring (black arrows). The channel entrance is occupied by a β-DDM molecule. e Proton half-channels shown in red (lumenal) and blue (matrix) colours and compared to gaps (dotted black circles) in detergent density (dark gold) of the cryo-EM density map of the dimer.

The missing interactions of truncated H1-4a are compensated by lipids and apicomplexan subunits and extensions surrounding the canonical subunits, anchoring them to the enlarged Fo region and the wing region (Figs. 2b and 3a). Thus, the minimal T. gondii subunit-a exemplifies an evolutionary mechanism that combines subunit truncation and reduced hydrophobicity with structural compensation that allowed gene transfer. Together, our analyses illustrate how the substantial mitochondrial genome reduction occurred in apicomplexan parasites, retaining only three mitochondrial genes, while maintaining functional mitochondrial energy conversion.

The IF1-locked rotational state reveals salt bridge formation at the rotor-stator interface

In addition to minimal architecture and evolutionary insight, the subunit-a structure also reveals its interactions with the c-ring. The IF1-arrested structure, in which ATP synthases are locked in a single rotational state, allowed us to obtain a map of the rotor-stator interface at 3.5 Å (Supplementary Fig. 1d), resolving both the c-ring and H5-6 of subunit-a, where proton transfer occurs. Mechanistically, the essential arginine on H5a (Arg166 in T. gondii) is thought to be responsible for deprotonation of the conserved glutamate on the c-ring (Glu150 in T. gondii)29. Translocating protons enter Fo via a lumenal access channel, are transferred to the protonatable glutamate on the c-ring and released via a matrix channel34,35. While our cryo-EM map does not display unambiguous density for Glu150, previous X-ray crystal structures have shown that this side chain can adopt an open unprotonated or closed proton-locked rotamer36,37. Both formation and absence of a salt bridge between the arginine and glutamate have been observed in different structures29,38,39, including a suggestion of a bridging water molecule40.

Our structure indicates that in the open conformation Glu150 is within 2.3 Å distance from the juxtaposed Arg166, allowing the formation of a salt bridge (Fig. 4b). The rotor-stator interface surrounding the Arg166/Glu150 pair is more hydrophobic compared to other structures, with subunits a and c contributing a total of eight aromatic residue side chains (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 8e). Thus, the tight hydrophobic interface between the decameric c-ring and subunit-a in T. gondii is consistent with a direct, rather than water-mediated Arg/Glu interaction.

We traced two cavities in the Fo subcomplex corresponding to the proton half-channels on the lumenal and matrix sides (Fig. 4c, d, Supplementary Fig. 8g). The lumenal proton half-channel displays a hydrophilic entrance between subunit-a and ATPTG2 facing towards the c-ring (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 8f). Inside the membrane, the lumenal channel is lined by membrane-inserted loops of ATPTG2 and ATPTG3 and the C-terminal transmembrane helix of subunit-b (Fig. 4d). The channel extends through the only acidic patch between H5a and H6a near a conserved glutamate (Glu201), which is thought to mediate proton transfer to the c-ring (Supplementary Fig. 8f)29. The matrix half-channel locates to a hydrophilic region between subunits a, d, ATPTG16, ATPTG17 and extends into the membrane region towards R159 of H5a, which is widely conserved (Fig. 4c). Remarkably, the C-terminus of ATPTG16 contributes the only nearby carboxylate group, likely serving an equivalent role to acidic side chains thought to mediate proton release in ATP synthases of other organisms (Fig. 4c)24,28,29,38,41.

The lateral offset between the two proton half-channels is also evident in the density map, where discontinuation of the detergent belt matches the positions of the two half-channels in support of an aqueous environment for proton translocation (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 8g). Taken together, both half-channels are partially lined by apicomplexan-specific subunits resulting in a divergent structure and likely the involvement of different residues in proton translocation compared to structures from other organisms.

Peripheral stalk subunit-b contains a structural motif found in the mammalian subunit F6

The peripheral stalk extends from the membrane-embedded part of Fo and attaches to the tip of F1, holding it stationary against the torque of the central stalk. In T. gondii the peripheral stalk is composed of subunit-b, d, ATPTG12 and OSCP (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 9b). The attachment to F1 is mediated through OSCP, which adopts a fold conserved in prokaryotic and eukaryotic homologs (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Subunit-b displays structural similarity with its bacterial, algal and mammalian counterparts, engaging in conserved interactions with the C-terminal domain of OSCP as observed in other structures. Compared to the yeast and mammalian ATP synthases, T. gondii displays an augmented peripheral stalk structure with extensions in subunit-b, subunit-d and the additional ATPTG12 (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Unlike yeast and porcine24,39, neither subunit-f nor 8 (A6L in mammals) contribute to the peripheral stalk. Instead, the apicomplexan-conserved subunit ATPTG12 forms extensive interactions with subunit-b and d throughout the peripheral stalk structure (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Interestingly, peripheral stalk subunit F6 (subunit h in yeast) is not found in T. gondii ATP synthase. Instead, the C-terminal extension of subunit-b, adopts a fold that structurally resembles subunit F6/h and provides supporting interactions with the long subunit-b helix (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Both, the yeast subunit-h (on non-fermentable carbon sources) and the augmented T. gondii subunit-b are essential18,42, suggesting a critical role in peripheral stalk assembly.

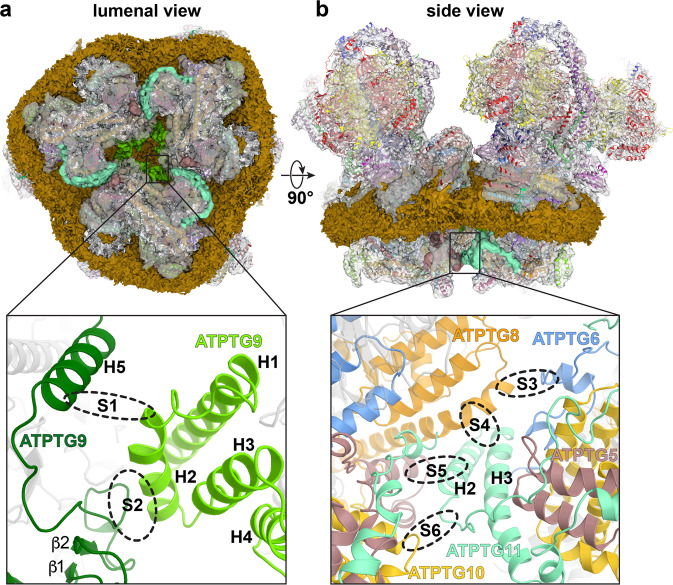

Formation of the ATP synthase hexamer involves two contact sites in the lumenal region

Next, we asked how ATP synthase dimers interact in the hexamer structure to form the cyclic trimer of dimers. The hexamer model shows that each of the three dimer-dimer interfaces contributes ~1211 Å2 to hexamer contacts. Those contacts holding the hexamer together are found in two separate sites in the lumenal regions, which form a triangular subcomplex (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5. Structure of T. gondii ATP synthase hexamer reveals two lumenal Fo contact sites between neighbouring dimers.

a First contact site is shown on the ATP synthase hexamer composite map viewed from the lumen with central lipid bilayer and surrounding detergent belt (gold). The lumenal regions of the three dimers interact to form a triangular complex (bottom panel). Three copies of the CHCHD protein ATPTG9 form homotypic interactions. b Second contact site is shown from the side view: tilted helix hairpin (H2, H3) of ATPTG11 mediates interactions with ATPTG5, ATPTG8 and ATPTG10, whereas ATPTG6 interacts with ATPTG8.

In the first site, three copies of the subunit ATPTG9 are arranged around the C3-symmetry axis, directly beneath the central lipid bilayer (Supplementary Fig. 2e, f). ATPTG9 contains two CHCHDs with cysteine pairs positioned to form disulfide bonds. CHCHD-containing subunits were reported to play a role in the assembly of Complex IV43. In our structure, H2 of the first CHCHD in one ATPTG9 copy interacts with H5TG9 and the loop connecting β2 and H5TG9 of a neighbouring ATPTG9 (Fig. 5a). Both interacting structural elements are predominantly hydrophilic, consistent with their solvent-accessible location in the lumen.

In the second site, located at the periphery of the lumenal region, ATPTG11 establishes a network of five interacting subunits. A helix hairpin of ATPTG11, containing a central cysteine pair, extends parallel to the membrane plane and mediates interactions between the dimers. H2TG11 contacts with subunits ATPTG5, ATPTG8 and ATPTG10, whereas H3TG11 interacts with ATPTG8 (Fig. 5b). Apart from the inward-facing residues, the ATPTG11 helix hairpin and interacting subunit segments are predominantly hydrophilic and solvent-exposed in the dimer.

For ATPTG9, we found that the four CX9C motifs are conserved in mitochondriate Apicomplexa (Supplementary Fig. 10a, d). Likewise, we identified apicomplexan orthologs of ATPTG5 and ATPTG11, including candidate genes in Plasmodium with conserved cysteine pairs of the helix hairpins and key residues, including the N-terminal helix of ATPTG11 (Supplementary Fig. 10b, c, e, f). These data suggest that mitochondrial ATP synthase hexamers are a common feature of Apicomplexa.

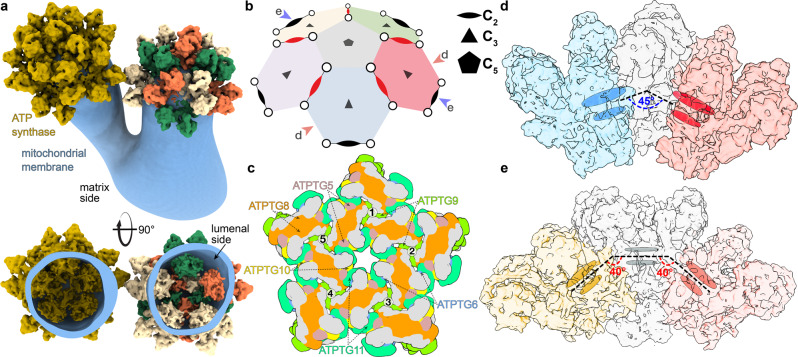

Hexamers specifically assemble into pentagonal pyramids in curved membrane regions

To investigate if the mitochondrial ATP synthase hexamers occur in situ, we performed cryo-ET of isolated T. gondii mitochondrial membranes. Tomograms showed that the inner-membrane vesicles frequently displayed bulbous protrusions decorated with ATP synthase arrays (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Movie 2). Using subtomogram averaging, we then obtained a 20-Å resolution map of the ATP synthase dimer, which agrees well with the atomic model (Supplementary Fig. 11a, c). The analysis of the macromolecular arrangement of ATP synthase dimers in the membrane suggested that they are arranged into regular arrays with a hexamer as the repetitive unit, confirming the occurrence of this cyclic oligomeric form in situ (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6. T. gondii ATP synthase arranges into pentagonal pyramids with icosahedral symmetry to induce membrane curvature.

a Cryo-ET of the mitochondrial membranes (blue) and subtomogram averaging of dimers reveals their macromolecular arrangement into pentagonal pyramids held together by proteins in the lumen. b Schematic representation shows five hexamers (coloured) arranged around a C5-axis. Red and blue arrows indicate cross-sections shown in the other panels. Inner and outer dimers are shown as red and black ellipses, respectively. c Schematic of interactions between luminal subunits involved in the assembly of the pentagonal pyramid. d Neighbouring hexamer planes (blue and red) are arranged at a ~45°-angle around the shared dimer (grey). e Cross section through the pentagonal ATP synthase pyramid showing two 40°-angles between hexamer (yellow, red) and pentamer (grey) planes.

Our data further show that these ATP synthase hexamers are arranged in larger arrays with icosahedral symmetry. The most frequently observed arrangement consists of ten ATP synthase dimers arranged into five hexamer units, forming a pentagonal pyramid (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Movie 2). In the pyramid, the five inner dimers form a pentameric interface, with the C5 symmetry axis centred on the apex of the vesicular protrusion (Fig. 5b). Each of the five inner dimers is shared by two neighbouring hexamer units (Fig. 5b).

To understand how the pentagonal pyramid induces the membrane curvature, we analysed cross-sections of the array (Fig. 6b, d, e). This showed that while the lipid bilayer within hexamers is near-planar (Supplementary Fig. 2e), neighbouring hexamers planes are related by a 45° angle (Fig. 6d). This is consistent with two times the 22° incline of each dimer with respect to the C3 symmetry axis through the hexamer plane (Figs. 1c, d and 5b), indicating that the single-particle hexamer structure is consistent with the in situ pyramid assembly. Thus, membrane curvature is induced locally around the five inner dimers. Furthermore, hexamer planes are oriented by 40° with respect to the pentamer plane formed in the centre of the pyramid (Fig. 6a, b, e).

Fitting the dimer models into the pentagonal pyramid array suggested that no additional contacts are formed at the pentamer site. This indicates that the assembly of the pentagonal pyramids is fully explained by the contacts between the lumenal regions. This involves the same interactions as in the hexamer (Figs. 5 and 6c). Due to the C2-symmetry of the dimer, each linker subunit is present in two copies, allowing the propagation of interactions (Fig. 6c), which results in the formation of a ~3.6-MDa array in the cristae lumen (Fig. 6a).

Pentagonal pyramids are required for maintenance of native cristae architecture

Toxoplasma tachyzoites are a model system to study mitochondrial functions in Apicomplexa, as they can be cultured using alternative energy sources to oxidative phosphorylation, thereby enabling the mutation of genes encoding proteins involved in mitochondrial energy conversion44. To investigate the role of ATP synthase hexamers in maintaining native cristae architecture, we generated a knockout line of ATPTG11 (Supplementary Fig. 12a–c). Native gel electrophoresis confirmed that dimer assembly occurs in the absence of ATPTG11 (Supplementary Fig. 12d), and cryo-ET of mitochondrial membranes isolated from the ATPTG11-KO line revealed an altered organisation of the dimers in situ (Fig. 7, Supplementary Movie 3). Particularly, instead of forming pentagonal pyramids (Fig. 7a, c), ATP synthase dimers were found loosely arranged into disordered or row-like arrays along flat membrane regions (Fig. 7b, d). This demonstrates that ATPTG11 lumenal interfaces hold the pentagonal pyramids together (Fig. 6c). Visualization of the ATPTG11-KO mitochondrial membranes by cryo-ET revealed an elongated tubular shape (Fig. 7d), indicating that the formation of hexamers and pentagonal pyramids is critical for the maintenance of the bulbous cristae morphology in T. gondii. Thus, the ATPTG11-KO demonstrates the role of specific oligomer contacts in cristae architecture.

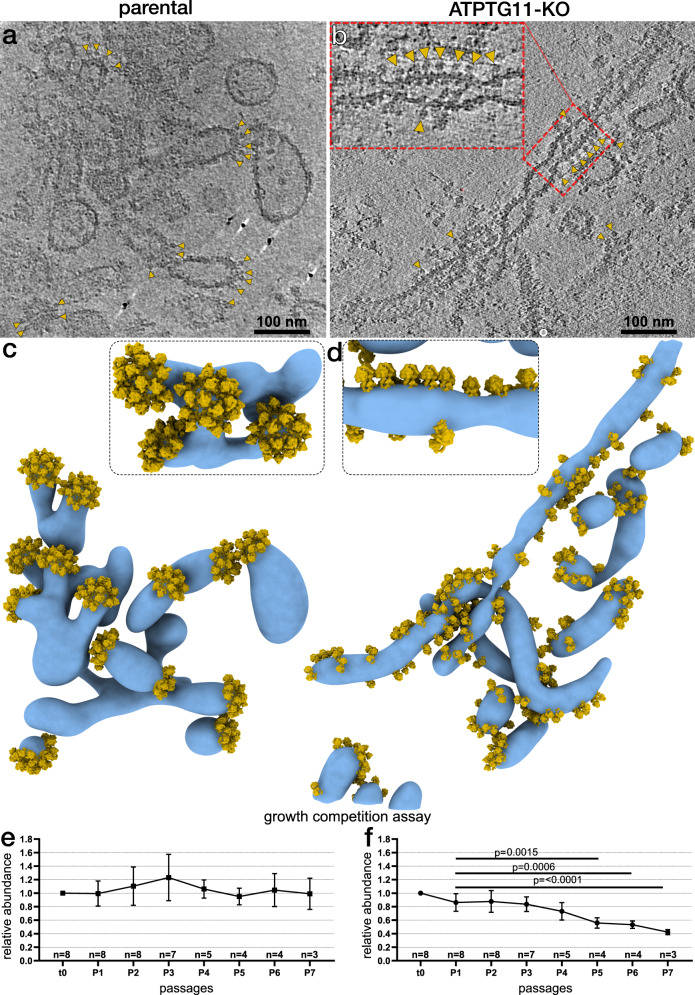

Fig. 7. Pentagonal pyramids are required for maintenance of the native cristae morphology.

a, b Parental strain (a) and ATPTG11-KO (b) cross sections of tomograms of mitochondrial membranes decorated with ATP synthase (yellow arrows). c, d Segmentation of mitochondrial membranes (blue) with repositioned subtomogram averages of the dimers (yellow). Whereas the parental strain forms pentagonal pyramids that cap the bulbous membrane protrusions, hexamer and pyramid formation is disrupted in ATPTG11-KO, and ATP synthase dimers arrange in row-like or disordered arrays along elongated or tubular membranes. Close-up views show the pentagonal pyramid in the parental strain and row-like arrangements in the mutant strain. e, f Relative abundances of parental (e) and ATPTG11-KO (f) of the mixed-culture growth competition assay as determined by qPCR of total gDNA, normalized to t0. Each passage represents 3–8 biological replicates; error bars are SD; p-values were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test comparing each passage to P1.

In addition, analysis of thin sections showed that ATPTG11-KO contains fewer cristae per mitochondrial area than the parental line, indicating an altered crista structure (Supplementary Fig. 13a–c). Flow cytometry using the potential-sensitive fluorescent dye JC-1 indicated that the mitochondria of ATPTG11-KO remain energized by a mitochondrial membrane potential, which is sensitive to the ionophore valinomycin, like the parental line (Supplementary Figs. 13d and 14). Fluorescence microscopy further revealed that the single large mitochondrion of both lines forms the characteristic lasso-shape, indicating that overall mitochondrial ultrastructure is not affected. Finally, we performed a growth competition assay where ATPTG11-KO parasites were grown in a mixed population with the parental line. Quantitative PCR of isolated genomic DNA (gDNA) during continued culturing showed that the relative abundance of the ATPTG11-KO decreased significantly (Fig. 7e, f). These results indicate that the loss of ATP synthase oligomers and aberrant morphology are linked to impaired parasite fitness, when compared to the parental line.

In summary, we demonstrate that ATPTG11-KO selectively disrupts the formation of higher oligomers, while assembly of dimers appears unaffected. The resulting mild phenotype in cultured tachyzoites is in contrast to the strong growth defect that accompanies ATP synthase disassembly following loss of the indispensable core subunit-b18. This suggests that T. gondii tachyzoites, which utilize both glycolysis45 and oxidative phosphorylation46 can compensate for the aberrant macromolecular organisation of ATP synthase, but not for the complete loss of its catalytic function.

Pentagonal pyramid arrays shape unique cristae of Toxoplasma mitochondria

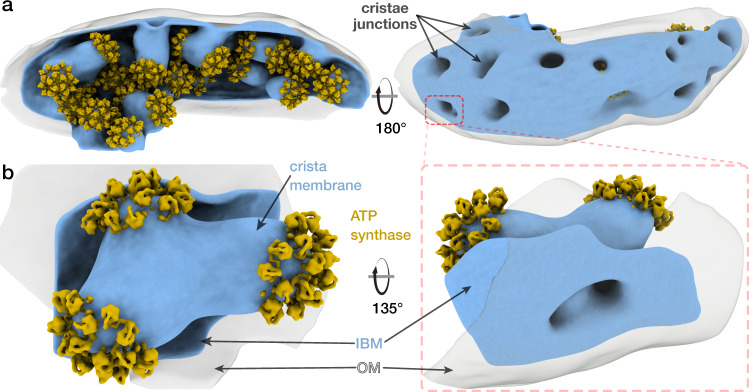

To confirm the occurrence of the pentagonal pyramids in organello, we performed cryo-ET of T. gondii mitochondria with a translucent matrix. The analysis showed that cristae display bulbous morphology and are attached to the inner boundary membrane by circular cristae junctions (Fig. 8a). The bulbous cristae protrusions are capped by apical arrays of ATP synthases arranged into the pentagonal pyramids (Fig. 8b, Supplementary Fig. 15). Thus, the apicomplexan cristae morphology is in stark contrast to the coiled tubular cristae found in the related phylum of ciliates, which are shaped by helical ATP synthase dimer rows and connected via one crista junction at either end47.

Fig. 8. Pentagonal ATP synthase pyramid arrays decorate bulbous cristae in T. gondii mitochondria.

a Cryo-ET of a T. gondii tachyzoite mitochondrion (IBM, inner boundary membrane, blue; OM, outer mitochondrial membrane, grey) and subtomogram averaging of ATP synthase dimers (yellow). Cristae are connected to the inner boundary membrane via circular cristae junctions and decorated with pentagonal ATP synthase pyramids. b Close-up view of a crista membrane containing three bulbous protrusions, each decorated with an ATP synthase array containing ten ATP synthase dimers.

In addition, recent cryo-EM structures of a ciliate ATP synthase dimer and tetramer showed that although both structures share a small dimer angle and a large lumenal region22, the two alveolate ATP synthases have diverged significantly and acquired lineage-specific subunits. Rather than forming hexamers, the ciliate-specific structural elements mediate dimer-dimer contacts that result in the formation of long helical ATP synthase dimer rows and cristae tubulation. Thus, the superphylum of alveolates contains at least two different types of ATP synthase dimers and cristae morphologies, differentiating the free-living and parasitic protist phyla.

Our data suggest that in the organellar context, the exclusive localisation of the ATP synthase in the curved membrane regions will result in its segregation from the respiratory chain complexes residing in the flat cristae regions6. Such preferential localization of proton sinks has been suggested to generate a directional proton flow along a lateral proton gradient inside the cristae48. Together with the recent visualisation of cristae as high-potential compartments12, these results suggest that assembly of a membrane-shaping ATP synthase oligomer drives its localisation to regions of high membrane potential, thus favouring ATP synthesis.

In summary, this work demonstrates that ATP synthase can be arranged in previously unseen high oligomeric arrays, which differ from the spontaneously assembled dimer rows, that were thought to be universal in all mitochondria5–7,47,49,50. We describe an organisational principle based on specific interactions between ATP synthase hexamers that are assembled into a pentagonal pyramid architecture. This results in the induction of local membrane curvature, which gives rise to the unique bulbous cristae morphology in Apicomplexa.

Methods

Cell culture and mitochondria isolation

T. gondii RH tachyzoites were grown in Vero cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% (w/v) FBS, 2% (w/v) L-glutamine and 29.9 mM penicillin, 17.2 mM streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% (v/v) CO2. For each mitochondrial preparation ~100 T150 flasks were harvested at >80% host-cell lysis and the media passed through 23G needles to fully lyse any remaining host cells. Parasites were pelleted by centrifugation at 1500 × g, 10 min, 4 °C, washed in PBS and then resuspended in buffer containing 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT to 5 × 108 cells/ml. Parasites were lysed by successive rounds of nitrogen cavitation (2500 PSI, 15 min incubation on ice) until >95% lysis (confirmed by light microscopy). After each round, the lysate was centrifuged at 1500 × g, 15 min, 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and the pellet resuspended in the same volume for further lysis.

The final combined lysate was centrifuged as before and the supernatant was spun again at 16,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C. The resulting crude mitochondrial pellet was further purified on a discontinuous sucrose gradient in 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 15/23/32/60% (w/v) sucrose by centrifugation (103,745 × g, 1 h, 4 °C) in an SW41 rotor (Beckman Coulter) and enriched mitochondria were collected from the 32–60% (w/v) interface.

Thin sectioning and conventional transmission electron microscopy

Infected human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) cultured in 6-cm dishes were washed gently with PBS. Light microscopy was used to ensure that the majority of extracellular parasites were removed. Host cells with intracellular parasites were gently scraped into 1.5 ml PBS and spun at 1500 × g for 10 min at RT. PBS was removed and cells were gently resuspended in freshly made fixation buffer (2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde, 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2), washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2 and post-fixed in 1% (w/v) OsO4, 1.25% (w/v) K4[Fe(CN)6] for 1 h on ice. After several washes in the same buffer, the samples were en bloc stained with 0.5% (w/v) uranyl acetate in water for 30 min. Afterwards, samples were washed with water, dehydrated in ascending acetone series and resin embedded. Ultrathin sections (~50 nm thick) were collected and imaged on a JEOL 1200 Transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) operated at 80 kV. Obtained images (66 parental; 63 ATPTG11-KO) were analyzed with the Fiji software51 and the number of individual cristae cross sections per mitochondrial area was calculated for the parental (80.8 ± 24.0 cristae/µm2; mean, SD; n = 118) and ATPTG11-KO lines (59.6 ± 21.8 cristae/µm2; mean, SD, n = 103).

ATPTG11 knockout line generation

ChopChop tool (https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/) was used to identify suitable gRNA near the start codon of the ATPTG11 gene (gRNA used: GATTGCGCACCATCTTGCAC). The gRNA was cloned under the U6 promoter (via BsaI restriction site) into a plasmid, which also encoded CAS9-GFP under the control of a TUB8 promoter52 using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 3. A dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) resistance cassette was amplified using the pDT7S4 plasmid as template53 and using primers containing 50 bp of sequence homology to regions upstream and downstream of the ATPTG11 open reading frame. The plasmid and PCR product were co-transfected into an RH ΔHX Δku80 TATi parasite strain53 and cassette integration was selected for with pyrimethamine for 8 days. The resulting parasite pool was cloned into 96-well plates with manual dilutions and 7 days later individual clones were tested by PCR for cassette integration using testing primers (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b).

Real-time quantitative PCR

To assess the expression level of ATPTG11 in the newly generated KO-line, ~5 × 106 freshly lysed parasites were filtered through 3-µm filters and collected by centrifugation. RNA was extracted from parasite pellets using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions with the following modification: DNA was additionally on-column digested with 1 µl of amplification grade DNaseI (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 15 min at RT during step 4 of the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were reverse transcribed to cDNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) following manufacturer’s protocol. Twenty nanograms of cDNA were then used in each qPCR reaction, which was set up with Power SYBR Green Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific) with 300 nM of each primer. All qPCR reactions were performed using a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using default temperature settings and performing a dissociation step after each run. Relative gene expression was determined using the ΔΔCT method54 using T. gondii catalase as an endogenous reference. The experiment was performed for ATPTG11-KO and the parental parasite line using primers against the unmodified ATPTG11 locus.

Growth competition assay

A confluent HFF monolayer was inoculated with ~1:1 ratio of ATPTG11-KO and parental parasites and incubated as described above. After complete host cell lysis, the collected parasites were mixed thoroughly, a new HFF dish was inoculated and the remaining parasites were filtered (3-µm pore size) and collected for gDNA extraction. gDNA was extracted using QiaGen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit. Power SYBR Green Master Mix, 300 nM of each primer and 10 ng of gDNA were used to perform quantitative PCR (7500 Real-Time PCR System using default settings with added dissociation step). The relative abundance of each parasite line was calculated relative to T. gondii catalase and normalized to the first collection point (to) using the ∆∆ct method54 using the primers against the native locus and DHFR. Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 8.4.3.

Immunofluorescence assay and microscopy

Parasites were inoculated on fresh HFFs on glass coverslips. After 1-day cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilised and blocked with a solution in 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.2% (v/v) triton X-100 in PBS before incubation with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-TgMys55), 1:1000, followed by secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor Goat anti-Rabbit 594 Invitrogen #A-11012, 1:1000). Coverslips were mounted on slides with Fluoromount-G mounting media containing DAPI (Southern Biotech, 0100-20). Images were acquired via a DeltaVision Core microscope (Applied Precision) using a ×100 objective55. A total of seven representative images of ATPTG11-KO (containing individual vacuoles) and 10 images of parental parasites (containing 44 individual vacuoles) were obtained from two biologically independent repeats. Images were processed and deconvolved using the SoftWoRx (Glasgow, UK) and Fiji software51.

Flow cytometry analysis of membrane potential using JC-1

Parasites grown in HFF were allowed to lyse the host cells. Collected parasites were filtered through a 3-μm filter and incubated in their growth media with 10 μM valinomycin for 30 min at 37 °C (as a depolarising control) or with an equal volume of DMSO, and then with 1.5 μM of JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolocarbocyanine iodide, Thermo Fisher Scientific, stock 1.5 mM in DMSO) for 15 min at 37 °C before analysis with the CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter Life Science), using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and a 585/42 nm bandpass filter for detection of red fluorescence. 50,000 events per condition were collected and data were analysed using FlowJo (FlowJo LLC) to visualise the population of parasites with red fluorescent signal.

Blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting

Whole parasites (5 × 106) were mixed with 5 μl solubilisation buffer (750 mM aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris–HCl pH 7.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) dodecyl maltoside) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The resulting lysate was centrifuged at 18,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min. Sample buffer was added to the supernatant (NativePAGE™ 5% (w/v) G-250 Sample Additive and NativePAGE™ Sample Buffer (4X) (Invitrogen™), with a final concentration of Coomassie of 0.0625% (w/v)), resulting in a final concentration of 0.25% (w/v) dodecyl maltoside. NativePAGE™ Running Buffer (20X) and NativePAGE™ Cathode Buffer Additive (20X) (Invitrogen™) were mixed to reconstitute the anode, dark and light cathode buffers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were loaded on 3-12% (v/v) Bis-Tris Gel (Novex- Life technologies) and 5 μl NativeMark™ (Invitrogen) was used as a molecular weight marker. Gels were run for 1 h at 80 V, 10 mA at 4 °C with dark cathode buffer, then for ~2 h at 200 V, 6 mA with light cathode buffer.

Proteins were transferred from the gel onto a methanol-soaked PVDF membrane (0.45 μm, Hybond™). Wet transfer in Towbin buffer (0.025 M Tris 0.192 M glycine 10% (v/v) methanol) was performed for 60 min at 100 V. The membrane was stained with Coomassie solution (50% methanol, 7% (v/v) acetic acid, and 0.05% (w/v) Coomassie R250 (Serva)) to visualise the molecular weight marker, and destained with 50% methanol, 7% acetic acid. Blots were labelled with primary rabbit anti-ATP-β (1:2000, Agrisera) coupled to secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP) anti-rabbit (Promega) conjugated antibodies (1:10,000) and visualised using the Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Purification of T. gondii ATP synthase dimers and hexamers

Enriched mitochondria were lysed in a total volume of 34 ml buffer containing 25 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 15 mM MgOAc2, 2% (w/v) β-DDM, 2 mM DTT, 1 tablet EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail for 2 h at 4 °C and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 30,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C. The supernatant was layered on a sucrose cushion in buffer of 1 M sucrose, 25 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 15 mM MgOAc2, 1% β-DDM, 2 mM DTT, and centrifuged 230,759 × g, 4 h, 4 °C in a Ti70 rotor (Beckman Coulter). The resulting pellet was resuspended in 200 µl 25 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 15 mM MgOAc2, 2 mM DTT, 0.05% β-DDM, and gel filtrated over a Superose 6 Increase 3.2/300 column (GE Healthcare). Fractions corresponding to ATP synthase dimers were pooled and concentrated to 25 µl in a vivaspin500 filter (100-kDa MWCO). Purification of ATP synthase hexamers was performed similarly to that of dimers, but substituting β-DDM with identical concentrations of digitonin.

Electron cryo-microscopy and data processing

3 µl ATP synthase dimer sample (~5 mg/ml) were applied to glow-discharged Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 Cu grids and vitrified by plunge-freezing into liquid ethane after blotting for 3 s. The ATP synthase dimer was imaged on a Titan Krios operated at 300 kV at a magnification of 165 kx (0.85 Å/pixel) with a Quantum K2 camera (slit width 20 eV) at an exposure rate of 7.5 electrons/pixel/s with a 4-s exposure fractionated into 20 frames56 using the EPU software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A total of 4860 collected movies were motion-corrected and exposure-weighted using MotionCor257 and contrast transfer function (CTF) estimation was performed using Gctf58. Subsequent image processing was performed in RELION-3 (Supplementary Fig. 1)59. Bad images were removed manually by inspection in real- and Fourier-space. References for particle picking were generated from the data by Gaussian-blob picking and initial rounds of refinement and classification. Reference-based particle picking was performed using Gautomatch (developed by Dr Kai Zhang, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK, http://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/kzhang/Gautomatch) to pick 275,030 particles, which were subjected to reference-free two-dimensional (2D) classification, resulting in 214,085 particles for three-dimensional (3D) classification, from which 101,505 particles were selected. Masked refinements of the entire dimer and the membrane region with applied C2-symmetry yielded maps of at 2.8 Å and 2.9 Å resolution, respectively. The pre-aligned particles were C2-symmetry expanded and one monomeric unit was signal subtracted. Using masked 3D refinement, maps of the OSCP/F1/c-ring, peripheral stalk and the rotor were obtained at 3.1 Å, 3.5 Å and 3.5 Å resolution, respectively. For final map generation, the original, rather than signal-subtracted particles were used. Focused classification of the F1/c-ring and IF1 binding regions did not reveal a presence of additional rotational states, or classes missing IF1. Therefore, the inhibition by IF1 is likely the result of the biochemical preparation.

T. gondii ATP synthase hexamers (19 mg/ml) were frozen as described above and imaged on a Titan Krios operated at 300 kV equipped with a K2 Summit detector and energy filter (20 keV slit width). Two datasets with a total of 7604 micrographs were acquired at a nominal magnification of 130 kx (1.05 Å/pixel) with a total exposure of 32 electrons/Å2 over 6.5 s, fractionated into 20 frames. Initial picking references were generated from the data for reference-based particle picking using Gautomatch. Subsequent image processing in RELION-3 using 2D and 3D classifications (Supplementary Fig. 2) yielded a 4.8-Å resolution map of the hexamer membrane region from 4532 particles.

All final maps were generated from CTF-refined particles. All resolution estimates are according to Fourier shell correlations (FSC) that were calculated from independently refined half-maps using the 0.143-criterion with correction for the effect of the applied masks (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Electron cryo-tomography and subtomogram averaging

Crude T. gondii mitochondria pellets from either the parental or ATPTG11-KO strain were resuspended in an equal volume of buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 250 mM sucrose and mixed in a 1:1 ratio with 5-nm colloidal gold solution (Sigma Aldrich) and vitrified as described above on glow-discharged Quantifoil R2/2 Cu grids. Tilt series were acquired on a Titan Krios operated at 300 kV with a Quantum K2 camera (slit width 20 eV) using serialEM60 or the EPU software. Mitochondrial membranes were imaged at a nominal magnification of 64 kx (2.21 Å/pixel) and an exposure rate of 1.5 electrons/pixel/s with a 2-s exposure fractionated into four frames with tilt series acquired using the exposure-symmetric scheme61 to ±60° tilt and a 3° tilt increment. Mitochondrial ghosts were imaged at a nominal magnification of 33 kx (4.27 Å/pixel) and an exposure rate of 11.5 electrons/pixel/s with a 3-s exposure fractionated into 3 frames. Bidirectional tilt series were acquired from −60° to 60° starting at 24° with a 2° tilt increment and a defocus range of −5 to −8 µm. Frames were motion-corrected and exposure-weighted using MotionCor257 and CTF estimation was performed using Gctf58.

Tomographic reconstruction was performed in IMOD62 using phaseflipping63 and a binning factor 2. Tomograms were contrast enhanced using nonlinear anisotropic diffusion filtering64 to facilitate manual particle picking of ATP synthases. Subtomogram averaging was performed in PEET65. Initial references were generated from the data by averaging after rotating subvolumes into a common orientation with respect to the membrane. Following initial rounds of subtomogram averaging, false-positive particles were removed based on a cross-correlation coefficient cut-off and manually by visual inspection of their orientation (e.g. removal of upside-down particles). Particles were then split into odd and even half-sets and aligned to independently updated references using C2 symmetry using a mask around the ATP synthase dimer. A 20-Å resolution map was obtained from 139 ATP synthase dimers from one tomogram of mitochondrial membranes (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 15b), whereas a 22-Å resolution map of the ATPTG11-KO dimer was obtained from 269 particles from two tomograms. A 34-Å resolution map was obtained from 410 ATP synthase dimer particles from one tomogram of a T. gondii mitochondrion (Supplementary Fig. 15). Final maps were lowpass-filtered according to the 0.143-FSC criterion using RELION66.

Atomic model building and refinement

Manual building of atomic models was performed in Coot67. Fo subunits were built de novo using reconstructions of Fo and peripheral stalk respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Built subunits were verified by BLAST searches against two libraries of putative T. gondii ATP synthase subunits18,68. Three Fo subunits were identified by BLAST search using the built sequences against ToxoDB (toxodb.org) (Extended Data Table 1). OSCP/F1/c-ring models were built using a homology model69 of the yeast F1/c10-ring (PDB ID 3ZRY) [10.2210/pdb3ZRY/pdb]70, whereas OSCP C-terminal domain and IF1 were built de novo in an F1/c-ring masked reconstruction. A total of two adenosine diphosphate molecules were resolved in three of the β-subunits, whereas three ATP molecules were resolved in the three alpha subunits. The database sequence the C-terminal helix of the α-subunit did not match the density map, but the manual building of the helix successfully identified the correct sequence for this part, corroborated by a single transcriptome study71. Real-space refinement of atomic models was performed in PHENIX72 using secondary structure restraints and Rosetta73. Bound cardiolipins were unambiguously identified from their head group density. Other natively bound lipids were tentatively modelled as phosphatidyl choline or phosphatidyl ethanolamine, based on head group densities. To generate a composite model of the complete ATP synthase dimer, the atomic models of the membrane region, the OSCP/F1/c-ring and the peripheral stalk were combined after rigid-body fitting into the consensus map of the dimer and refined in PHENIX using reference restraints. For the generation of an atomic model of the ATP synthase hexamer, individual models of ATP synthase dimer membrane region, peripheral stalk and F1/c-ring were manually fitted into the hexamer reconstruction using Chimera74. The model fragments were combined into a single model file in Coot. The final hexamer model was real-space refined in PHENIX using the secondary structure and reference model restraints. Model statistics were calculated using MolProbity75 and EMRinger76. To evaluate potential overfitting of the atomic models during refinement, the atomic coordinates of the refined models were randomly displaced by shifts up to 0.5 Å using ‘Shake’ in the CCPEM suite77. The shaken models were real-space refined using PHENIX against one-half map that had been reference-sharpened using Refmac78. Subsequently, FSCwork and FSCtest between the model and the two unfiltered half-maps, were calculated as described78.

Data analysis and visualisation

Homology searches for T. gondii ATP synthase subunits across Myzozoans were performed in Eupath DB, EnsemblProstits and NCBI, using tBLASTn. The TGGT1_246540 gene (ATPTG1) is annotated on Toxo DB as cytochrome c1. This is due to the sequence containing two parts: the modelled ATPTG1 and a cytochrome c1. Because no part of the cytochrome c1 was found in the structure, homology searches were performed using the modeled ATPTG1 sequence only. This finding is consistent with a recent mass spectrometry study identifying peptides from the ATPTG1/cytochrome c1 gene in both T. gondii ATP synthase and complex III (10.1101/2020.08.17.252163).

The luminal half-channel was traced as a void in the Fo-model, using the Caver plugin for PyMOL79. Calculation of subunit a surface electrostatics was done using APBS80. Images were rendered using PyMOL 2 (Schrödinger, LLC), Chimera74 or ChimeraX81. The composite map of the ATP synthase dimer was generated in Chimera. This map was only used for visualisation, but not for atomic model refinement, where instead a consensus map was used. Prediction of cleavage sites of the mitochondrial matrix protease was performed using MitoFates82. Surface areas of subunit contacts were estimated using the PISA server for the dimerization interface or ChimeraX for the hexamer interface. Segmentation of membranes in tomographic volumes was performed manually in AMIRA (Thermo Scientific). Macromolecular arrangement of ATP synthase dimers was visualised by placing the subtomogram averages into the positions and orientations determined by subtomogram averaging using the clonevolume command in IMOD83.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the ESRF beamline CM01 for provision of beam time for experiment MX-2107, and would like to thank especially Eaazhisai Kandiah for the excellent support. We thank the Astbury Biostructure Laboratory at the University of Leeds for tomography data collection, and especially Rebecca Thompson for her dedicated help. We also thank Michael Hall for data collection at the SciLifeLab National cryo-EM facility. We thank Leandro Lemgruber of Glasgow Imaging Facility for his support and assistance in this work, members of Sheiner lab for help with parasite growth and harvesting, members of the Kuvin Center for the Study of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for providing work space and support with flow cytometry work. This work was funded by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (FFL15:0325), Ragnar Söderberg Foundation (M44/16), European Research Council (ERC-2018-StG-805230), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (2018.0080), BBSRC (BB/N003675/1), Wellcome Investigator award (217173/Z/19/Z). A.M. is supported by an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship (ALTF 260-2017). A.A. is supported by the EMBO Young Investigator Program. L.S. is a Royal Society of Edinburgh Personal Research Fellow. The SciLifeLab cryo-EM facility is funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg, Family Erling Persson, and Kempe foundations.

Source data

Author contributions

A.M., L.S. and A.A. designed the project. A.M., P.F., A.L., J.O., L.S. and A.A. performed preparation of mitochondria from parasites. L.S. and J.O. generated the mutant line. A.M. performed protein purification and biochemical characterization, prepared cryo-EM grids, collected and processed EM data. A.M. and R.K.F. built, refined and validated the structures. A.M., R.K.F. and A.A. wrote the manuscript with help from L.S. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Data availability

The atomic coordinates were deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession numbers 6TMG (membrane region), 6TMH (F1/c-ring), 6TMI (peripheral stalk), 6TMJ (rotor-stator), 6TMK (F1Fo dimer) and 6TML (hexamer). The cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession numbers EMD-10520 (membrane region), EMD-10521 (F1/c-ring), EMD-10522 (peripheral stalk), EMD-10523 (rotor-stator), EMD-10524 (F1Fo dimer), EMD-10525 (hexamer), EMD-10526 (subtomogram average from mitochondrial membranes), EMD-11403 (subtomogram average from ATPTG11-KO mitochondrial membranes) and EMD-10527 (subtomogram average from mitochondria). Previously reported structural data includes accession numbers EMDB-0667, PDB 3ZRY, PDB 5X3P, PDB 2TRX), PDB 2LQL, PDB 6RD4, PDB 6B8H, PDB 6N2Y, PDB 6J5K, PDB 6J5I, PDB 6RD9, PDB 6CP6. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Alexander Mühleip, Rasmus Kock Flygaard.

Contributor Information

Lilach Sheiner, Email: lilach.sheiner@glasgow.ac.uk.

Alexey Amunts, Email: amunts@scilifelab.se.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20381-z.

References

- 1.Boyer PD. The binding change mechanism for ATP synthase—some probabilities and possibilities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1140:215–250. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90063-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noji H, Yasuda R, Yoshida M, Kinosita K., Jr. Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature. 1997;386:299–302. doi: 10.1038/386299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morales-Rios E, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Structure of ATP synthase from Paracoccus denitrificans determined by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:13231–13236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517542112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn, A., Vonck, J., Mills, D. J., Meier, T. & Kühlbrandt, W. Structure, mechanism, and regulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase. Science10.1126/science.aat4318 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Strauss M, Hofhaus G, Schröder RR, Kühlbrandt W. Dimer ribbons of ATP synthase shape the inner mitochondrial membrane. EMBO J. 2008;27:1154–1160. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies KM, et al. Macromolecular organization of ATP synthase and complex I in whole mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14121–14126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103621108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum, T. B., Hahn, A., Meier, T., Davies, K. M. & Kühlbrandt, W. Dimers of mitochondrial ATP synthase induce membrane curvature and self-assemble into rows. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 10.1073/pnas.1816556116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Davies KM, Anselmi C, Wittig I, Faraldo-Gomez JD, Kühlbrandt W. Structure of the yeast F1Fo-ATP synthase dimer and its role in shaping the mitochondrial cristae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13602–13607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204593109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paumard P, et al. The ATP synthase is involved in generating mitochondrial cristae morphology. EMBO J. 2002;21:221–230. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bornhövd C, Vogel F, Neupert W, Reichert AS. Mitochondrial membrane potential is dependent on the oligomeric state of F1F0-ATP synthase supracomplexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13990–13998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell P. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature. 1961;191:144–148. doi: 10.1038/191144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf, D. M. et al. Individual cristae within the same mitochondrion display different membrane potentials and are functionally independent. EMBO J. 10.15252/embj.2018101056 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kühlbrandt, W. Structure and mechanisms of F-Type ATP synthases. Annu. Rev. Biochem.10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-110903 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Tenter AM, Heckeroth AR, Weiss LM. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int J. Parasitol. 2000;30:1217–1258. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacot, D., Meissner, M., Sheiner, L., Soldati-Favre, D. & Striepen, B. in Toxoplasma Gondii(2nd Edn.) (eds Weiss, L. M. & Kim, K.) 577–611 (Academic Press, 2014).

- 16.Ferguson, D. J. P. & Dubremetz, J.-F. in Toxoplasma gondii (3rd Edn.) (eds Weiss, L. M. & Kim, K.) 21–61 (Academic Press, 2020).

- 17.Aikawa M, Huff CG, Sprinz H. Comparative fine structure study of the gametocytes of avian, reptilian, and mammalian malarial parasites. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1969;26:316–331. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5320(69)80010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huet, D., Rajendran, E., van Dooren, G. G. & Lourido, S. Identification of cryptic subunits from an apicomplexan ATP synthase. eLife10.7554/eLife.38097 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Sturm A, Mollard V, Cozijnsen A, Goodman CD, McFadden GI. Mitochondrial ATP synthase is dispensable in blood-stage Plasmodium berghei rodent malaria but essential in the mosquito phase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10216–10223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423959112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez E, et al. The mitochondrial respiratory chain of the secondary green alga Euglena gracilis shares many additional subunits with parasitic Trypanosomatidae. Mitochondrion. 2014;19:338–349. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mühleip, A., McComas, S. E. & Amunts, A. Structure of a mitochondrial ATP synthase with bound native cardiolipin. eLife10.7554/eLife.51179 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kock Flygaard, R., Mühleip, A., Tobiasson, V. & Amunts, A. Type III ATP synthase is a symmetry-deviated dimer that induces membrane curvature through tetramerization. Nat. Commun. 10.1038/s41467-020-18993-6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hahn A, et al. Structure of a complete ATP synthase dimer reveals the molecular basis of inner mitochondrial membrane morphology. Mol. Cell. 2016;63:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu J, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the mammalian ATP synthase tetramer bound with inhibitory protein IF1. Science. 2019;364:1068–1075. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw4852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. How the regulatory protein, IF(1), inhibits F(1)-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15671–15676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabezon E, Runswick MJ, Leslie AG, Walker JE. The structure of bovine IF(1), the regulatory subunit of mitochondrial F-ATPase. EMBO J. 2001;20:6990–6996. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.6990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinke, G., Zhou, L. & Sazanov, L. A. Cryo-EM structure of the entire mammalian F-type ATP synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 10.1038/s41594-020-0503-8 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Guo, H., Suzuki, T. & Rubinstein, J. L. Structure of a bacterial ATP synthase. eLife10.7554/eLife.43128 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Guo H, Bueler SA, Rubinstein JL. Atomic model for the dimeric FO region of mitochondrial ATP synthase. Science. 2017;358:936–940. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allegretti M, et al. Horizontal membrane-intrinsic α-helices in the stator a-subunit of an F-type ATP synthase. Nature. 2015;521:237–240. doi: 10.1038/nature14185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daley DO, Clifton R, Whelan J. Intracellular gene transfer: reduced hydrophobicity facilitates gene transfer for subunit 2 of cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:10510–10515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122354399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjorkholm P, Harish A, Hagstrom E, Ernst AM, Andersson SG. Mitochondrial genomes are retained by selective constraints on protein targeting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10154–10161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421372112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waller, R. F., Keeling, P. J., van Dooren, G. G. & McFadden, G. I. Comment on “A green algal apicoplast ancestor”. Science301, 49; author reply 49 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Vik SB, Antonio BJ. A mechanism of proton translocation by F1F0 ATP synthases suggested by double mutants of the a subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:30364–30369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Junge W, Lill H, Engelbrecht S. ATP synthase: an electrochemical transducer with rotatory mechanics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;22:420–423. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Symersky J, et al. Structure of the c(10) ring of the yeast mitochondrial ATP synthase in the open conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:485–491, S481. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pogoryelov D, Yildiz O, Faraldo-Gomez JD, Meier T. High-resolution structure of the rotor ring of a proton-dependent ATP synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1068–1073. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klusch, N., Murphy, B. J., Mills, D. J., Yildiz, O. & Kühlbrandt, W. Structural basis of proton translocation and force generation in mitochondrial ATP synthase. eLife10.7554/eLife.33274 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Srivastava, A. P. et al. High-resolution cryo-EM analysis of the yeast ATP synthase in a lipid membrane. Science10.1126/science.aas9699 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Murphy, B. J. et al. Rotary substates of mitochondrial ATP synthase reveal the basis of flexible F1-Fo coupling. Science10.1126/science.aaw9128 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Spikes TE, Montgomery MG, Walker JE. Structure of the dimeric ATP synthase from bovine mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:23519–23526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013998117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arselin G, Vaillier J, Graves PV, Velours J. ATP synthase of yeast mitochondria. Isolation of the subunit h and disruption of the ATP14 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:20284–20290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cavallaro G. Genome-wide analysis of eukaryotic twin CX9C proteins. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6:2459–2470. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00058b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oppenheim RD, et al. BCKDH: the missing link in apicomplexan mitochondrial metabolism is required for full virulence of Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium berghei. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004263. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacRae JI, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism of glucose and glutamine is required for intracellular growth of Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vercesi AE, Rodrigues CO, Uyemura SA, Zhong L, Moreno SN. Respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:31040–31047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mühleip AW, et al. Helical arrays of U-shaped ATP synthase dimers form tubular cristae in ciliate mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:8442–8447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525430113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rieger B, Junge W, Busch KB. Lateral pH gradient between OXPHOS complex IV and F0F1 ATP-synthase in folded mitochondrial membranes. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3103. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mühleip AW, Dewar CE, Schnaufer A, Kühlbrandt W, Davies KM. In situ structure of trypanosomal ATP synthase dimer reveals a unique arrangement of catalytic subunits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:992–997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612386114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anselmi C, Davies KM, Faraldo-Gomez JD. Mitochondrial ATP synthase dimers spontaneously associate due to a long-range membrane-induced force. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018;150:763–770. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201812033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curt-Varesano A, Braun L, Ranquet C, Hakimi MA, Bougdour A. The aspartyl protease TgASP5 mediates the export of the Toxoplasma GRA16 and GRA24 effectors into host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:151–167. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheiner L, et al. A systematic screen to discover and analyze apicoplast proteins identifies a conserved and essential protein import factor. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002392. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ovciarikova J, Lemgruber L, Stilger KL, Sullivan WJ, Sheiner L. Mitochondrial behaviour throughout the lytic cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42746. doi: 10.1038/srep42746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kandiah E, et al. CM01: a facility for cryo-electron microscopy at the European Synchrotron. Acta Crystallogr D. Struct. Biol. 2019;75:528–535. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319006880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang K. Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 2016;193:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zivanov, J. et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife10.7554/eLife.42166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hagen WJH, Wan W, Briggs JA, et al. Implementation of a cryo-electron tomography tilt-scheme optimized for high resolution subtomogram averaging. J. Struct. Biol. 2017;197:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiong QR, Morphew MK, Schwartz CL, Hoenger AH, Mastronarde DN. CTF determination and correction for low dose tomographic tilt series. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;168:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hegerl R, Frangakis AS. Noise reduction in electron tomographic reconstructions using nonlinear anisotropic diffusion. J. Struct. Biol. 2001;135:239–250. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nicastro D. Cryo-electron microscope tomography to study axonemal organization. Method Cell Biol. 2009;91:1–39. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)91001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salunke R, Mourier T, Banerjee M, Pain A, Shanmugam D. Highly diverged novel subunit composition of apicomplexan F-type ATP synthase identified from Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2006128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waterhouse A, et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Giraud MF, et al. Rotor architecture in the yeast and bovine F1-c-ring complexes of F-ATP synthase. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;177:490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramaprasad A, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of Toxoplasma gondii VEG and Neospora caninum LIV genomes with tachyzoite stage transcriptome and proteome defines novel transcript features. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Afonine PV, et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol. 2018;74:531–544. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318006551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DiMaio F, Tyka MD, Baker ML, Chiu W, Baker D. Refinement of protein structures into low-resolution density maps using rosetta. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;392:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barad BA, et al. EMRinger: side chain-directed model and map validation for 3D cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:943–946. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burnley T, Palmer CM, Winn M. Recent developments in the CCP-EM software suite. Acta Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol. 2017;73:469–477. doi: 10.1107/S2059798317007859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brown A, et al. Tools for macromolecular model building and refinement into electron cryo-microscopy reconstructions. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2015;71:136–153. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714021683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jurcik A, et al. CAVER Analyst 2.0: analysis and visualization of channels and tunnels in protein structures and molecular dynamics trajectories. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3586–3588. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goddard TD, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018;27:14–25. doi: 10.1002/pro.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fukasawa Y, et al. MitoFates: improved prediction of mitochondrial targeting sequences and their cleavage sites. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2015;14:1113–1126. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.043083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kremer, J. R., Furcinitti, P. S. & McIntosh, J. R. New image-modeling software used for 3-D analyses of biological electron microscopy data on silicon graphics computers. Proc. Ann. Meet MSA, 334–335 (1994).

- 84.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moon CP, Fleming KG. Side-chain hydrophobicity scale derived from transmembrane protein folding into lipid bilayers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10174–10177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103979108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wimley WC, White SH. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:842–848. doi: 10.1038/nsb1096-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ojaimi J, Pan J, Santra S, Snell WJ, Schon EA. An algal nucleus-encoded subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase rescues a defect in the analogous human mitochondrial-encoded subunit. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:3836–3844. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e02-05-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement