Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a major cause of foodborne gastroenteritis worldwide inflicting palpable socioeconomic costs. The ability of this pathogen to successfully infect its hosts is determined not only by the presence of specific virulence genes but also by the pathogen’s capacity to appropriately regulate those virulence genes. Therefore, DNA methylation can play a critical role in both aspects of this process because it serves as both a means to protect the integrity of the cellular DNA from invasion and as a mechanism to control transcriptional regulation within the cell. In the present study we report the comparative methylome data of C. jejuni YH002, a multidrug resistant strain isolated from retail beef liver. Investigation into the methylome identified a putative novel motif (CGCGA) of a type II restriction-modification (RM) system. Comparison of methylomes of the strain to well-studied C. jejuni strains highlighted non-uniform methylation patterns among the strains though the existence of the typical type I and type IV RM systems were also observed. Additional investigations into the existence of DNA methylation sites within gene promoters, which may ultimately result in altered levels of transcription, revealed several virulence genes putatively regulated using this mode of action. Of those identified, a flagella gene (flhB), a RNA polymerase sigma factor (rpoN), a capsular polysaccharide export protein (kpsD), and a multidrug efflux pump were highly notable.

Keywords: Campylobacter jejuni, methylome, methylation, restriction-modification system, virulence gene

Introduction

Campylobacteriosis is one of the most frequently acquired bacterial infections associated with the consumption of contaminated foods. Symptoms of campylobacteriosis include diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, cramps, and fever. Although the infection is often self-limiting, its prevalence is a cause of concern for the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2020). Most cases of campylobacteriosis are caused by Campylobacter jejuni, a bacterium that exists as a commensal organism in the gastrointestinal tract of many domestic animal populations that are utilized as food sources such as poultry, cattle, pigs, and sheep (Facciola et al., 2017). Factors that influence the virulence of Campylobacter in humans are currently under investigation in an effort to devise better methods to control and/or prevent its spread.

DNA sequencing has become a driver for many scientific advancements over the past few decades. Sequence-based methods are now commonly used to identify bacterial virulence factors and as bioinformatic approaches advance, the frequency of utilizing comparative genomic analyses to identify genes involved with virulence continues to rise. Such analyses have already led to the identification of the pVir plasmid in Campylobacter jejuni (Bacon et al., 2002). With the rapid progress in whole genome sequencing (WGS) technology over last decade, the study of bacterial foodborne pathogens has gained new dimensions, which has provided further insight into the biology of these organisms (Llarena et al., 2017). In addition to generating genome sequences, Single Molecule Real Time (SMRT) technology offers a tool for studying epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation. In bacteria, DNA methylation is a base modification system that is catalyzed by methyltransferases and results in the formation of the following: C5-Methyl-cytosine (m5C), N6-methyl-adenine (m6A), and N4-methyl-cytosine (m4C) (Sanchez-Romero et al., 2015). These modified bases enable the cell to identify and eliminate foreign DNA via the bacterial restriction-modification (RM) system, which has been shown to cleave double stranded DNA fragments. The resulting fragments are then further degraded by other endonucleases within the cell, essentially destroying any foreign DNA that may have been introduced that threatens the integrity of the cellular DNA. RM systems are common amongst bacteria with all four classes of RM systems (types I–IV) having been identified in C. jejuni1.

Methylation sites that are embedded within promoter regions or other regulatory sites may also serve as a mechanism by which genes, including virulence genes, can be regulated. For example, the presence of two DNA methylase targets within the regulatory region of the well-studied pyelonephritis-associated pilus (pap) operon has been shown to establish fimbrial phase variation in Escherichia coli populations by modifying the binding sites of a transcriptional regulatory factor involved in the process (van der Woude et al., 1996). It has been suggested by Mou et al. (2015) that DNA methylation may also be involved in the pathogenicity of C. jejuni, leading to some of the variations in disease presentation that can be seen amongst strains sharing a high degree of genomic synteny and sequence homology. This idea is further supported by gene products like that of cj1461, a N6-adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase that has been shown to play a role in factors related to pathogenicity including motility, adherence, and invasion in C. jejuni (Kim et al., 2008).

Overall, the study of methylomes is still in its infancy, with only a few reports available for C. jejuni (Murray et al., 2012; Mou et al., 2015; O’Loughlin et al., 2015) and none for a C. jejuni food isolate. In this context, we undertook the methylation analysis of the C. jejuni YH002, a strain isolated from beef liver, and compared/contrasted it with two well-studied C. jejuni strains to provide a deeper understanding into the biology of this important foodborne pathogen.

Materials and Methods

Detection and Analysis of Methylated Bases in C. jejuni YH002

The strain C. jejuni YH002 was isolated from retail beef liver using a passive filtration method (Speegle et al., 2009; Jokinen et al., 2012). The identity of the strain was confirmed by real-time PCR targeting the hipO gene (He et al., 2010). For genomic DNA preparation, the strain was grown in Brucella broth (Difco, Becton Dickinson, NJ) for approximately 40 h under microaerophilic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2) at 42°C and pelleted by centrifugation. High quality genomic DNA for SMRT sequencing was extracted and purified using the Qiagen Genomic-tip 100/G kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Library preparation and SMRT sequencing was provided by the University of Delaware Sequencing and Genotyping Center (Newark, DE). The complete genome sequence and annotation are available in GenBank of NCBI with the accession No. CP020776 for the 1,774,584 bp chromosome and No. CP020775 for the 45,904 bp plasmid (pCJP002) (Ghatak et al., 2020).

Detection of methylated bases in the genome of C. jejuni YH002 was performed by using SMRT Analysis Suite 2.3.02 with default parameters. Additional analyses were undertaken with various modified QV settings using the MotifMaker tool3.

The methylation locations in the C. jejuni YH002 genome were obtained by searching the 41 nucleotide (nt) context sequence of each motif in the raw PacBio data against the complete genome sequence. The average methylation frequency for each motif in the genome was calculated by dividing the number of occurrences of a particular methylation motif in either the chromosome or the plasmid by the total number of kilobase pairs in the chromosome (1,774.6 Kb) or the plasmid (45.9 Kb), respectively. All coding sequences (CDS) and gene products were predicted by RAST annotation4. The methylation frequency of the RAATTY motif in each CDS, rRNA, and tRNA was determined using a custom function added in Macros of Excel.

Comparative Analysis Amongst C. jejuni Strains

For the comparative assessment of the methylomes, published motif data of C. jejuni 81–176 and C. jejuni NCTC 11168 were downloaded from REBASE database (Roberts et al., 2015). Genomes of C. jejuni 81–176 and NCTC 11168 were searched for motifs with a P-value cut off < 0.001 as described previously (Grant et al., 2011). Methylated and un-methylated CDS were then determined using RAST annotation and methylation data (Quinlan and Hall, 2010).

Identification of Methylated Promoters

The locations of the transcriptional start sites (TSSs) in the C. jejuni YH002 chromosome were identified by sequence mapping the 50 nt region upstream of the TSSs in C. jejuni NCTC 11168, which were previously determined for C. jejuni NCTC 11168 using RNA-Seq data obtained from biological replicates during mid-log growth (Dugar et al., 2013). The C. jejuni YH002 chromosome is known to share high sequence similarity with C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (Ghatak et al., 2020). Similarly, the locations of the TSSs in the C. jejuni YH002 plasmid were identified by mapping the 50 nt sequences upstream of the TSSs in pTet in C. jejuni 81-176 since these two plasmids have 99% sequence similarity. In the present analysis, only those TSS deemed as either a primary or secondary TSS by Dugar et al. (2013) were utilized during the mapping process. All matched promoter sequences in C. jejuni YH002 were then checked for overlap with the methylated bases within the genome, ultimately deducing the promoter regions that were methylated (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Plots of methylated and un-methylated CDS regions were generated using Circos (Krzywinski et al., 2009).

Results

Methylation Detection, Motifs, and Distribution Patterns

Detection of base modifications during SMRT sequencing of the C. jejuni YH002 genome identified putative methylation motifs (Table 1). Because generating motifs using the default settings in the modification analysis of the SMRT sequencing platform might not be ideal in all cases for motif identification (Methylome-Analysis-Technical-Note)5, we undertook a comparative analysis with various modification QV (modQV) cut-off values ranging from 30 to 200. Though the results (Table 1) indicated the presence of m6A and m4C types of modifications in the C. jejuni YH002 genome, low occurrences of m4C type modification, inconsistent detections, and their bizarre patterns were likely indications of spurious detection by the software (Motif maker) and therefore, we did not consider them as valid motifs in our results. Mean coverage of motif detection varied from 225X to 299X indicating satisfactory analysis. Overall, the results yielded 8–12 motifs depending on the modQV cut-off values. Among these, 7 motifs (Table 1) appeared consistently in all the analyses. Of the seven motifs, four motifs formed two pairs of bipartite motifs (herby named ACNNNNNCTC/GAGNNNNNGT and TAAYNNNNNTGC/GCANNNNNRTTA), and another motif (RAATTY) was palindromic. Search of REBASE database for similar motifs in Campylobacter genomes confirmed our results.

TABLE 1.

Motifs identified in the genome of C. jejuni YH002 with various Modification QV (modQV) parametersa.

| modQV cutoff | Motif string | Typeb | Fraction (%) | Occurrence in genome | Partner motif | Mean IPD ratioc | Objective score |

| 30 | RAATTY | m6A | 99.0 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.839 | 11290815.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 99.3 | 2,085 | − | 5.604 | 752000.4 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 99.1 | 1,555 | − | 5.950 | 613870.3 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 99.5 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.449 | 446525.9 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 99.4 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 5.992 | 439943.8 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 99.7 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.407 | 225513.5 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 99.0 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.725 | 216201.3 | |

| HNNNNNARGTAAYG | m6A | 57.9 | 164 | − | 3.443 | 6120.3 | |

| GNNAGAGWANNNGND | m6A | 43.3 | 104 | − | 3.330 | 515.1 | |

| GCGGNAATNNNGNG | mod_base | 100.0 | 6 | − | 2.462 | 363.0 | |

| DGNNNNACCTVAY | m6A | 19.2 | 99 | − | 2.413 | 325.6 | |

| 40 | RAATTY | m6A | 98.9 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.840 | 11278810.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 99.0 | 2,085 | − | 5.603 | 750188.0 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 98.8 | 1,555 | − | 5.957 | 612288.7 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 99.5 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.449 | 446525.9 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 99.3 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 5.996 | 439218.7 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 99.5 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.405 | 225145.7 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 98.9 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.727 | 215850.6 | |

| CAGNTAANCANNNNNNA | mod_base | 77.8 | 9 | − | 1.914 | 366.1 | |

| 50 | RAATTY | m6A | 98.8 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.841 | 11266493.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 99.0 | 2,085 | − | 5.603 | 750188.0 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 98.6 | 1,555 | − | 5.958 | 611083.9 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 99.3 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.451 | 445776.1 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 99.2 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 6.000 | 438851.8 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 99.0 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.403 | 224003.4 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 98.7 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.726 | 215486.2 | |

| GAGADNNNGMTR | m6A | 52.7 | 186 | − | 2.468 | 5510.5 | |

| DNNBNACCTGAY | m6A | 43.3 | 90 | − | 2.448 | 1770.6 | |

| HNNNNACGCGANANNNA | m6A | 92.9 | 14 | − | 2.722 | 1673.6 | |

| 70 | RAATTY | m6A | 98.6 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.842 | 11236039.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 98.6 | 2,085 | − | 5.605 | 746719.4 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 98.0 | 1,555 | − | 5.966 | 606910.3 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 98.9 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.455 | 443441.6 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 98.8 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 6.007 | 436927.9 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 98.7 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.405 | 223224.5 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 98.2 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.734 | 214349.2 | |

| WNNNNCRSGAATNT | m4C | 36.2 | 149 | − | 3.571 | 4449.8 | |

| GAGWDNNNGMTR | m6A | 30.5 | 325 | − | 2.611 | 4048.9 | |

| 100 | RAATTY | m6A | 97.8 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.848 | 11142688.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 97.4 | 2,085 | − | 5.608 | 736426.2 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 97.0 | 1,555 | − | 5.969 | 599839.9 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 97.7 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.457 | 437677.1 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 97.5 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 6.012 | 430320.7 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 97.7 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.409 | 220690.8 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 96.4 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.753 | 209890.8 | |

| ARGTAATGNNNNND | m6A | 48.0 | 150 | − | 3.691 | 5429.8 | |

| WNNNNCRSGAATNT | m4C | 33.6 | 149 | − | 3.646 | 4023.6 | |

| HHNNNNNACGCGANNNB | m6A | 43.8 | 80 | − | 3.375 | 2962.1 | |

| CCCTGANNNRNANT | m4C | 88.9 | 9 | − | 3.508 | 1441.8 | |

| 140 | RAATTY | m6A | 96.7 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.852 | 10980916.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 95.7 | 2,085 | − | 5.620 | 720469.8 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 95.3 | 1,555 | − | 5.977 | 587514.6 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 96.4 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.456 | 430640.8 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 95.9 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 6.013 | 421956.2 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 95.3 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.408 | 214009.7 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 94.7 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.757 | 205157.1 | |

| DNNNNCRSGAATNT | m4C | 28.3 | 159 | − | 3.809 | 3330.1 | |

| HNNNNNARGTAATG | m6A | 29.3 | 150 | − | 4.008 | 2475.4 | |

| CGCGASTNNANNNNND | m6A | 100.0 | 8 | − | 4.424 | 2365.0 | |

| DNNDCCCTGAY | m4C | 25.9 | 85 | − | 3.430 | 1375.3 | |

| ACGCGANNNNNNTNANW | m6A | 100.0 | 6 | − | 3.118 | 1085.0 | |

| 170 | RAATTY | m6A | 96.0 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.855 | 10886096.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 94.4 | 2,085 | − | 5.630 | 708218.3 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 94.1 | 1,555 | − | 5.979 | 578480.0 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 95.8 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.456 | 426831.5 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 94.8 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 6.036 | 415825.4 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 94.3 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.409 | 211109.1 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 92.9 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.773 | 200120.3 | |

| DNNNNCRSGAATNT | m4C | 23.9 | 159 | − | 3.997 | 2560.3 | |

| CGCGASTNNANNNNND | m6A | 100.0 | 8 | − | 4.424 | 2365.0 | |

| 200 | RAATTY | m6A | 95.3 | 30,196 | RAATTY | 5.863 | 10775063.0 |

| CCYGA | m6A | 92.9 | 2,085 | − | 5.646 | 691808.3 | |

| GKAAYG | m6A | 93.2 | 1,555 | − | 5.983 | 571029.3 | |

| ACNNNNNCTC | m6A | 95.5 | 1,226 | GAGNNNNNGT | 5.457 | 425312.0 | |

| GAGNNNNNGT | m6A | 93.9 | 1,226 | ACNNNNNCTC | 6.049 | 410360.9 | |

| TAAYNNNNNTGC | m6A | 92.2 | 618 | GCANNNNNRTTA | 5.424 | 204586.9 | |

| GCANNNNNRTTA | m6A | 90.8 | 618 | TAAYNNNNNTGC | 5.784 | 193836.7 | |

| DNNNNCRSGAATNT | m4C | 28.2 | 103 | − | 4.008 | 2328.9 | |

| CGCGAGTWNA | m6A | 100.0 | 5 | − | 4.488 | 1530.0 |

aModified bases are boldfaced. bmod_base: undetermined modification. cIPD: Inter-pulse duration.

Manual analysis of the remaining identified motifs (those not included in the consistently detected motifs described above) indicated that most were either a part of or an extension of those previously described motifs. However, a closer analysis revealed that among the set of motif strings which were not part of the motifs detected in all modQV runs was the putative hidden motif, CGCGA. We believe this to be a novel motif for Campylobacter species as our search in the REBASE database did not yield a match. However, an exact match was noticed for Streptococcus mutans (GenBank Accession CP044495), which was isolated from the oral cavity of a human.

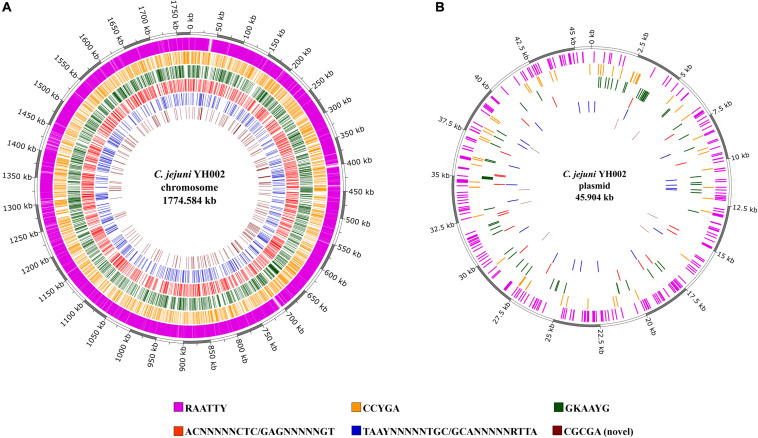

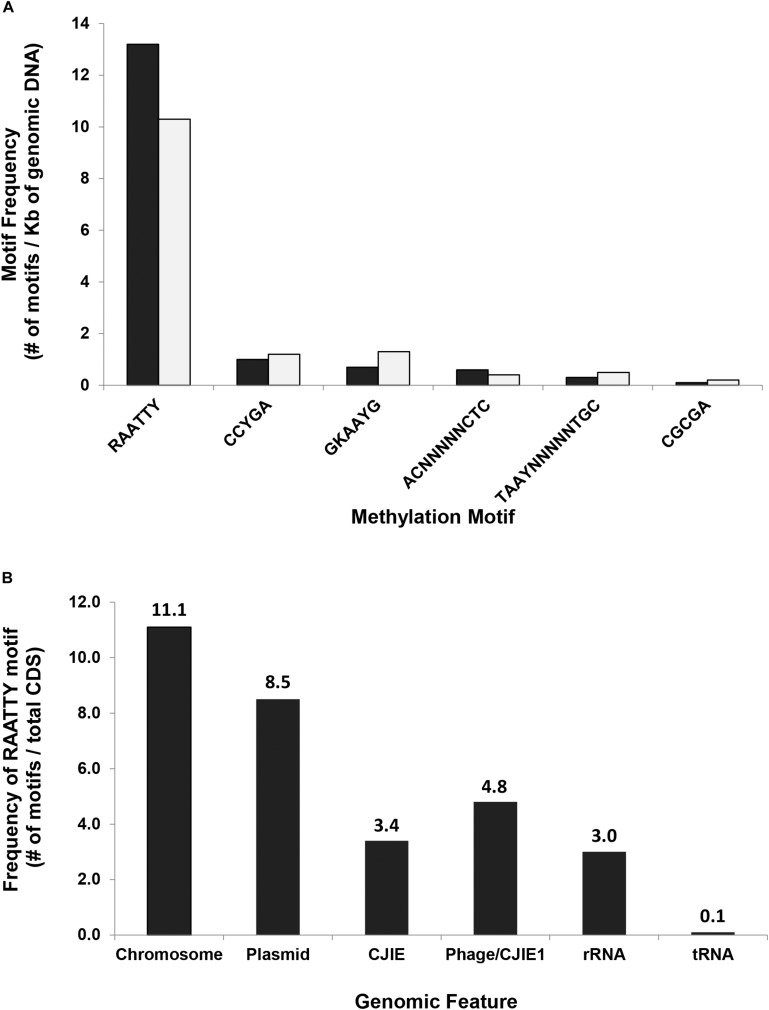

The consistently observed motifs were almost always (90.8–99.5%) methylated in the genome of C. jejuni YH002, with modification of the motif RAATTY being the predominant motif in both the chromosome and the pCJP002 plasmid (Figure 1). This is in agreement with a similar analysis performed on a recently emergent C. jejuni sheep abortion clone known as C. jejuni IA3902 (Mou et al., 2015). A comparison of the frequencies associated with the different methylation motifs in C. jejuni YH002 demonstrated that both the RAATTY and the ACNNNNNCTC/GAGNNNNNGT motifs showed a slightly higher frequency in the chromosome compared to the plasmid (Figure 2A). However, the frequency of the CCYGA, GKAAYG, TAAYNNNNNTGC/GCANNNNNRTTA, and the CGCGA motifs were higher in the plasmid by comparison. Although the distribution of the RAATTY motif appeared relatively uniform across both the chromosome and the plasmid of C. jejuni YH002 (Figure 1), an in-depth analysis of the frequency of the RAATTY (the predominant motif) demonstrated the existence of both hypomethylated and hypermethylated areas that were associated with specific genomic features/CDS (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). In this analysis, a value of 1 indicated that a single methylated site of the RAATTY motif in a CDS. Values greater than 40 indicated that CDS could be hypermethylated and those less than 1 indicated the possibility of hypomethylated CDSs (Mou et al., 2015). Based on this, CDS within the chromosome of C. jejuni YH002 contained an average of 11.1 RAATTY motifs per CDS (Figure 2B). However, certain CDS contained ≥ 60 RAATTY motifs, with the number of RAATTY motifs highest for a putative type IIS restriction-modification enzyme (78), a possible restriction-modification protein (64), the glutamate synthase [NADPH] large chain (60), and a DNA methylase (66) encoded for the plasmid (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). On the other extreme were the genes encoding tRNA, with a RAATTY frequency of 0.1 (Figure 2B), which indicated that many tRNA genes did not contain this methylation motif (Supplementary Table 1). Both integrated genetic elements (phage/CJIE1 and CJIE) and rRNAs had a considerably lower frequency of RAATTY compared to the chromosome and plasmid.

FIGURE 1.

Methylation motifs within C. jejuni YH002. The locations of the methylated areas within both the (A) chromosome (GenBank accession No. CP020776) and (B) plasmid (GenBank accession No. CP020775) of C. jejuni YH002 are highlighted by their individual methylation motifs.

FIGURE 2.

Methylation motif frequency in C. jejuni strain YH002. (A) The frequencies of six different methylation motifs in either the chromosome (black) or the plasmid (gray) were calculated using the number of a particular methylation motif divided by the total size of the chromosome (1,774.6 Kb) or the plasmid (45.9 Kb), respectively. (B) In-depth analysis of the frequency of the RAATTY motif within different genomic features was determined using the number of RAATTY motifs within a genomic feature divided by the total number of CDS in that genomic feature. Chromosome, C. jejuni YH002 chromosome; Plasmid, pCJP002; Phage/CJIE1, located between bp 1,409,078–1,444,627 in C. jejuni YH002;, and CJIE, Integrated mobile element located between bp 1,223,758–1,309,551 in C. jejuni YH002.

Comparative Analysis of Methylation in the Genomes of C. jejuni YH002, C. jejuni 81–176, and C. jejuni NCTC 11168

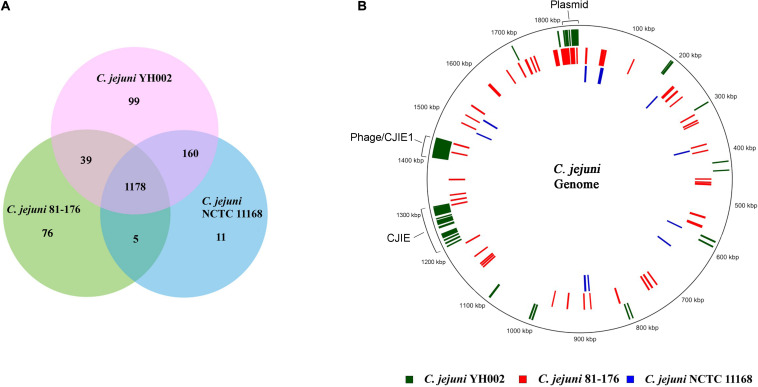

For the comparative analysis of the methylation patterns, previously reported methylation motifs from the REBASE database for the C. jejuni strains 81–176 and NCTC 11168 were obtained and the methylated CDS in all three genomes identified. Analysis of these CDSs revealed that a majority of the methylated CDSs (n = 1,178) were common among the three strains, though some uniquely methylated CDSs were also identified in each genome: 99 for C. jejuni YH002, 76 for C. jejuni 81–176, and 11 for C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (Figure 3A and Table 2). Mapping of these uniquely methylated CDSs revealed discernible patterns (Figure 3B) with the uniquely methylated genes more uniformly distributed in the genome of C. jejuni 81–176 compared to the other two genomes (YH002 and NCTC 11168).

FIGURE 3.

Comparative analysis of the methylome of the C. jejuni strains YH002, 81–176 and NCTC 11168. The Venn diagram (A) depicts the overlapping and unique CDSs methylated among C. jejuni YH002, C. jejuni 81–176, and C. jejuni NCTC 11,168, while the schematic (B) shows the relative locations of the uniquely methylated CDSs in the three C. jejuni genomes. The locations of the plasmid-borne genes are also shown.

TABLE 2.

Proteins encoded by CDS uniquely* methylated amongst the three strains of C. jejuni YH002, 81–176, and NCTC 11168.

| C. jejuni YH002 | C. jejuni 81–176 | C. jejuni NCTC11168 |

| Chromosome | ||

| TnpV | Protein of unknown function DUF262 family | ATP synthase protein I |

| Mobile element protein | Cytochrome c, putative | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Peroxide stress regulator; Ferric uptake regulation protein; Fe2 + /Zn2 + uptake regulation proteins | Thiol:disulfide interchange protein (dsbC), putative | Drug resistance transporter, Bcr/CflA family |

| FIG01371694: hypothetical protein | Gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase | FIG001196: Membrane protein YedZ |

| tRNA-Thr-TGT | LSU ribosomal protein L21p | FIG00469472: hypothetical protein |

| FIG00470965: hypothetical protein | FIG00470268: hypothetical protein | FIG00469493: hypothetical protein |

| Family of unknown function (DUF450) family | Predicted amino-acid acetyltransferase complementing ArgA function in Arginine Biosynthesis pathway | hypothetical protein |

| First ORF in transposon ISC1904 | Small-conductance mechanosensitive channel | L-threonine 3-O-phosphate decarboxylase |

| ATP synthase protein I-like membrane protein | Putative helix-turn-helix motif protein | Nicotinate-nucleotide adenylyltransferase/Iojap protein |

| Para-aminobenzoate synthase, amidotransferase component | Peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase | Para-aminobenzoate synthase, aminase component |

| Hypothetical domain/C-terminal domain of CinA type S | Ubiquinone/menaquinone biosynthesis methyltransferaseUbiE @ 2-heptaprenyl-1,4-naphthoquinone methyltransferase | Putative type IIS restriction/modification enzyme, C-terminal half |

| Putative Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase; Mercuric ion reductase; PF00070 family, FAD-dependent NAD(P)-disulphideoxidoreductase | LSU ribosomal protein L32p | − |

| FIG00471123: hypothetical protein | 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase | − |

| tRNA-Phe-GAA | FIG00469601: hypothetical protein | − |

| FIG00471396: hypothetical protein | FIG00388607: hypothetical protein | − |

| tRNA-Ser-TGA | FIG00469384: hypothetical protein | − |

| CJIE in chromosome: | tRNA-Gly-TCC | − |

| FIG00469806: hypothetical protein | LSU ribosomal protein L33p | − |

| Death on curing protein, Doc toxin | UbiD family decarboxylase associated with menaquinone via futalosine | − |

| Thymidine kinase | FIG00470496: hypothetical protein | − |

| FIG00470782: hypothetical protein | FIG00470712: hypothetical protein | − |

| Phage antirepressor protein | FIG00471113: hypothetical protein | − |

| TraD, putative | FIG00472079: hypothetical protein | − |

| HD domain protein | FIG00469622: hypothetical protein | − |

| M protein, putative | FIG00470120: hypothetical protein | − |

| pilT protein, putative | FIG00469655: hypothetical protein | − |

| Hypothetical phage protein, putative | FIG00470478: hypothetical protein | − |

| FIG00470684: hypothetical protein | FIG00469686: hypothetical protein | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraF | tRNA-Gly-GCC | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraW | 4-methyl-5(beta-hydroxyethyl)-thiazole monophosphate synthesis protein | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraU | FIG00469538: hypothetical protein | − |

| Transcriptional regulator, XRE family | LSU ribosomal protein L34p | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer surface exclusion protein TraT | Beta-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase | − |

| Thioredoxin, putative | Beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase | − |

| FIG00471674: hypothetical protein | ATP synthase F0 sector subunit a | − |

| Domain of unknown function (DUF332) superfamily | N-Acetyl-neuraminatecytidylyl transferase | − |

| FIG00471014: hypothetical protein | Peptidyl-prolylcis-trans isomerase | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraH | Menaquinone via 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine step 1 | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraC | Protein containing aminopeptidase domain | − |

| Phosphonate ABC transporter phosphate-binding periplasmic component (TC 3.A.1.9.1) | Formyltransferase domain protein | − |

| FIG00470688: hypothetical protein | MGC82361 protein | − |

| Conjugative transfer protein TraV | tRNA-Ser-GCT | − |

| Thiol:disulfide involved in conjugative transfer | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FliL | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraB | GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraK | LSU ribosomal protein L13p (L13Ae) | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein TraE | FIG00626672: hypothetical protein | − |

| IncF plasmid conjugative transfer pilus assembly protein | ATP/GTP-binding protein | − |

| FIG00471953: hypothetical protein | Anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase chain A | − |

| F-box DNA helicase 1 | Anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase chain B | − |

| Phage/CJIE1 in chromosome: | Anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase chain C | − |

| FIG00471569: hypothetical protein | Ribonuclease HI | − |

| FIG00471570: hypothetical protein | RepA protein homolog | − |

| DNA adenine methylase | tRNA-Leu-TAG | − |

| Phage virion morphogenesis protein, putative | Mll5128 protein | − |

| Phage tail length tape-measure protein | FIG00470615: hypothetical protein | − |

| Phage major tail tube protein, putative | LSU ribosomal protein L4p (L1e) | − |

| Major tail sheath protein | Lipopolysaccharide core biosynthesis protein LpsA | − |

| FIG00470503: hypothetical protein | tRNA-Ala-GGC | − |

| FIG00469719: hypothetical protein | Plasmid: | − |

| FIG00470940: hypothetical protein | FIG00471024: hypothetical protein | − |

| Tail fiber protein H, putative | DNA transformation competency | − |

| Baseplate assembly protein J, putative | Type IV secretion/competence protein (VirB9) | − |

| Baseplate assembly protein W, putative | Type II/IV secretion system ATP hydrolase TadA/VirB11/CpaF, TadA subfamily | − |

| FIG00470824: hypothetical protein | FIG00469544: hypothetical protein | − |

| Baseplate assembly protein V | FIG00469919: hypothetical protein | − |

| FIG00470123: hypothetical protein | Hypothetical protein pVir0008 | − |

| Phosphonate ABC transporter phosphate-binding periplasmic component (TC 3.A.1.9.1) | Hypothetical protein pVir0010 | − |

| FIG00470179: hypothetical protein | Hypothetical protein pVir0012 | − |

| FIG00471901: hypothetical protein | Hypothetical protein pVir0015 | − |

| Mu-like prophage I protein, putative | Hypothetical protein pVir0016 | − |

| FIG00469991: hypothetical protein | RepE replication protein, putative | − |

| FIG00472447: hypothetical protein | FIG00470162: hypothetical protein | − |

| Phage protein | FIG00472444: hypothetical protein | − |

| FIG00471796: hypothetical protein | FIG00472140: hypothetical protein | − |

| Prophage MuSo1, F protein, putative | Toxin-antitoxin protein, putative | − |

| Phage tail protein, putative | − | − |

| Putative regulator of late gene expression | − | − |

| DNA-binding protein, putative | − | − |

| Endonuclease I precursor | − | − |

| FIG00470704: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00471749: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00469659: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| Host-nuclease inhibitor protein Gam, putative | − | − |

| FIG00471516: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00470000: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| DNA transposition protein | − | − |

| Bacteriophage DNA transposition protein A, putative | − | − |

| FIG00470129: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| Phage repressor protein, putative | − | − |

| FIG00469983: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| Plasmid: | − | |

| Aminoglycoside phosphotransferase | − | − |

| FIG00472625: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00470991: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00469861: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| IncQ plasmid conjugative transfer protein TraG | − | − |

| FIG00471323: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00470038: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00469571: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| FIG00470457: hypothetical protein | − | − |

| Cag pathogenicity island protein (cag12) | − | − |

| FIG00472706: hypothetical protein | − | − |

*Unique methylation is defined as CDS methylated in only one of the three genomes.

Both C. jejuni YH002 and C. jejuni 81–176 have a collection of plasmid-borne genes that are not present in C. jejuni NCTC 11168. Interestingly, these plasmid-borne genes are also methylated (Figure 3B). The other two uniquely methylated regions in C. jejuni YH002 are both located in the integrated genetic elements (CJIEs). For C. jejuni YH002, this finding seems conflicted by the identification of proteins related to various components of putative RM systems, including Type I RM systems (Ghatak et al., 2020) and the presence of the genes encoding McrBC, which is responsible for specific restriction activity against methylated bases (usually 5 mC or 5 hmC).

Analysis of Methylation Locations in Gene Promoters

To enhance our ability to define genes that may be regulated by methylation, methylated sites located in gene promoter regions were identified by searching the known methylated sites within the −50 nt promoter sequences obtained by sequence mapping to the C. jejuni NCTC 11168 promoters (Dugar et al., 2013). Methylated bases were found in the promoter regions of 18 different hypothetical genes and 123 genes with predicted functions (Supplementary Table 3). Interestingly, several virulence genes were found to contain methylated nucleotides within their promoter region. This finding indicates a role for methylation in the transcription regulation of these genes, which includes flhB, rpoN, kpsD, multidrug resistance genes, and CRISPRs.

Further analysis of these promoter regions revealed the existence of all 6 different methylation motifs. Once again, RAATTY was the most dominant motif, having been identified 76 times within the predicted methylated promoters. The remaining motifs were found much less frequently, with CCYGA identified twice, GKAAYG identified three times, ACNNNNNCTC/GAGNNNNNGT identified once, TAAYNNNNNTGC/GCANNNNNRTTA identified seven time, and the CGCGA motif identified twice. The remaining methylated promoter regions did not appear to contain any of these defined methylation motifs, suggesting additional methylation motifs remain to be discovered and/or some of the six motifs extend beyond the −50 nt promoter sequences.

Discussion

Methylation of the genome plays several important roles in prokaryotic biology including acting as a defense mechanism against the incorporation of intruding nucleic acids into the bacterial host DNA and the regulation of gene expression by influencing transcription, replication initiation and mismatch repair (Murray et al., 2012; Mou et al., 2015; Blow et al., 2016). At the heart of host defense mechanisms utilizing methylation of host DNA is the restriction-modification (RM) system comprised of a restriction endonuclease (REase) and methyltransferase (MTase) (Murray et al., 2012; Blow et al., 2016). Of the four types (I–IV) of RM systems that have been reported, a majority have been classified as Type II systems (Blow et al., 2016). This is believed to be the result of technological difficulties in detecting the other RM systems (type I, type III, type IV) (Murray et al., 2012). However, this bottleneck has been mostly overcome with SMRT sequencing (Rhoads and Au, 2015), which has provided an opportunity to study the methylome of bacteria and contribute to the rapidly growing resource pool of methylation data (Roberts et al., 2015). Nonetheless, to date there are only a few reports on the methylome of Campylobacter isolates (Murray et al., 2012; Mou et al., 2015; O’Loughlin et al., 2015; Zautner et al., 2015) and to our knowledge there is no report on the methylome of C. jejuni originating from a food source. In our analysis we observed 7 motifs, of which 4 motifs were part of two bipartite pairs. Similar findings have been documented previously (Murray et al., 2012; Mou et al., 2015; O’Loughlin et al., 2015). In addition to the previously reported motifs, our results also identified a novel putative motif CGCGA for Campylobacter spp. as we did not find a match for this motif within the Campylobacter genomes in the REBASE database. However, an exact match with Streptococcus mutans was found, possibly indicated shared RM systems even across distant classes of bacteria (Epsilon-proteobacteria and Bacilli). During our analysis, we undertook a comparative modQV analysis to determine the effects of various cut-offs and also to derive a list of motifs with high confidence. Results suggested that comparative mod QV analysis is crucial for motif detection as various modQV cut-off values yielded varying results. Moreover, detection of base modifications by SMRT sequencing is known to produce secondary signals (usually 5 bases upstream m6A; 2 bases upstream 5 mC). Therefore, rigorous validation of software identified motifs is critical for correct motif identification as has been done in the present study.

Visualization of the methylated segments in the C. jejuni YH002 genome indicated widespread methylation covering almost 99% of the genome, which has been reported previously (Mou et al., 2015). Comparative analysis of the methylomes of three C. jejuni strains (YH002, 81–176 and NCTC 11168) highlighted that methylation patterns within a species are non-uniform and unlike that previously reported by O’Loughlin et al. (2015) we could not convincingly detect the m4C type of modification. However, these results coincide with those of a previous study where only the m6A type modification was documented in C. jejuni (Mou et al., 2015).

Detection of the mcrBC gene in the C. jejuni YH002 genome is also interesting considering this type IV RM system is methylation dependent for its restriction activity, which can restrict the establishment of any foreign DNA from sources such as bacteriophage that lack the proper DNA methylation. It is believed that methylation-specific RM systems such as this have evolved in response to an evolutionary arms race between bacteriophage and bacteria. As bacteriophages evolved mechanisms to allow for the invasion of bacterial cells, host bacteria have armed themselves with methylation-specific RM systems, which then force the bacteriophage to alter their genome if they are to avoid cleavage (Bickle and Kruger, 1993; Labrie et al., 2010; Sukackaite et al., 2012). Therefore, we believe the genome of C. jejuni YH002 may be unusual for possessing a type IV RM system (mcrBC) while simultaneously harboring two methylated bacteriophage elements. However, taking into account that McrBC only weakly restricts methylcytosines other than hydroxymethylcytosine (Ishikawa et al., 2010) and the suggested absence of m4C type methylation in the present analysis, the co-existence of both the methylated bacteriophage elements and the mcrBC system appears justifiable.

Methyltransferases that are typically involved in the regulation of gene expression often do not contain functional restriction-modification enzymes and are therefore referred to as orphan or solitary DNA methyltransferases. Methyltransferases of this type are important in cellular biology because of their ability to activate or silence genes without mutating the gene itself. Orphan methyltransferases can be found in C. jejuni YH002. For example, Accession # ARJ53876 (Ghatak et al., 2020) is a 227 amino acid protein found in C. jejuni YH002 whose sequence is identical to that of the N6-adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase cj1461 (Kim et al., 2008). The presence of orphan methyltransferases and the fact that multiple putative virulence genes were found in this study to contain methylation sites within their promoter regions (Supplementary Table 3) implies the ability of C. jejuni YH002 to employ this mode of regulation for the expression of certain virulence genes.

To uncover the genes that contained methylation sites within their promoter regions, the start of transcription was initially assessed. In this manuscript, TSSs were defined using data obtained from previously published RNA-seq experiments performed with biological replicates from specific C. jejuni strains during the mid-log phase of growth (Dugar et al., 2013). Although analysis in this fashion allowed the designation of a TSS to be based around experimental evidence instead of simply computational formulations, it is highly possible that some sites are missing from this analysis. For example, additional transcripts that were not assessed here may be produced by C. jejuni strains grown under alternative conditions. In addition, because the analysis relies upon those transcripts identified in C. jejuni NCTC 11,168 (which shares a high sequence similarity with C. jejuni YH002), transcripts unique to C. jejuni YH002 (e.g., CJIEs) would not be accounted for using this method. Regardless, TSSs regulated by σ70 as well as σ28 and σ54 were established using this method. It is also important to note that transcripts corresponding to many of the areas designated here were found in other C. jejuni strains including C. jejuni 81–176, C. jejuni 81116, and C. jejuni RM1221 using RNA-seq (Dugar et al., 2013), which helps highlight the reliability of the TSS predictions used.

Of the virulence genes identified that contained a methylation site within its promoter region, one appeared to be directly related to flagellum production (flhB). Much is known about the biopolar flagella in C. jejuni. With approximately 25–30 proteins involved in the assembly and function of flagella (Lertsethtakarn et al., 2011), this system was initially classified as a virulence factor based upon its role in the motility and the invasion of epithelial cells in the intestine (Morooka et al., 1985; Black et al., 1988; Wassenaar et al., 1991; Takata et al., 1992; Nachamkin et al., 1993). Additional investigations have shown these genes are also important not only for the secretion of non-flagellar proteins involved in virulence but that changes to the glycan composition of the flagella can affect autoagglutination, a preliminary step in biofilm formation, and evasion of the host’s immune response (Guerry, 2007). Insertional inactivation of flhB in C. jejuni resulted in mutants which were non-motile and had an altered cellular morphology (Matz et al., 2002). These mutants showed a significant reduction in the level of flaA transcript, demonstrating a role for FlhB in the regulation of flaA and thus indicating that the impact methylation has on the transcriptome may extend beyond those genes directly expressed from methylated promoters.

Another virulence gene in C. jejuni YH002 with widespread effects whose transcription is putatively regulated by DNA methylation is rpoN, which encodes for the σ54 protein. In general, sigma factors are global regulators involved with the recruitment of RNA polymerase to the promoter regions in which they are bound. Like other C. jejuni strains, C. jejuni YH002 appears to encode three sigma factors (Parkhill et al., 2000; Ghatak et al., 2020): (1) rpoD, which is considered the “housekeeping” sigma factor; (2) fliA, which regulates the flagellar operon;, and (3) rpoN, which has long been associated with a range of physiological phenomena and has recently been designated as a “central controller of the bacterial exterior” (Francke et al., 2011). Previous studies in C. jejuni have shown that not only is rpoN required for the transcription of a number of genes involved in bacterial motility (Hendrixson et al., 2001) but that rpoN mutants also lacked the presence of secreted proteins and are attenuated in their ability to both adhere to and be internalized by HeLa cells (Fernando et al., 2007). Interestingly, a transcriptional activator associated with σ54 was also found to contain a methylation site within its promoter; further establishing the importance of methylation for proper regulation of σ54 in C. jejuni.

Identification of a methylation site within the promoter regions of genes encoding the capsular polysaccharide export protein (KpsD), clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) genes, and a putative multidrug efflux pump are also worth mentioning because of their contributions to the survival, adaptation, and antibiotic resistance of C. jejuni (Bacon et al., 2001; Luangtongkum et al., 2009; Guerry et al., 2012; Louwen et al., 2014). Considering the multifaceted roles of these genes in virulence, the information presented here regarding methylation as a possible mode of regulation will be highly important for combating diarrheal disease caused by C. jejuni since its ability to successfully infect a hosts lies not only in the presence of specific virulence genes but also in the pathogen’s capacity to appropriately regulate those genes. Overall, studies such as this, which expand upon our knowledge of DNA methylation, serve to increase our understanding of how bacterial genomes are able to adapt to changes in the environment while simultaneously defending the integrity of the genetic material critical for their survival.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: GenBank of NCBI with the accession Nos. CP020776 and CP020775.

Author Contributions

CA and YH planned and analyzed experiments, authored, and edited the manuscript. SG planned, conducted, analyzed experiments, authored, and edited the manuscript. SR planned, conducted, analyzed experiments, and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

SG was thankful to Department of Biotechnology, New Delhi, India for Overseas Associateship Grant for NER (2015–16) and to Indian Council of Agricultural Research for necessary support. We would also like to thank Terence Strobaugh, Jr. for help with data collation.

Funding. This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS), Current Research Information System No. 8072-42000-084.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.610395/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bacon D. J., Alm R. A., Hu L., Hickey T. E., Ewing C. P., Batchelor R. A., et al. (2002). DNA sequence and mutational analyses of the pVir plasmid of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. Infect. Immun. 70 6242–6250. 10.1128/Iai.70.11.6242-6250.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon D. J., Szymanski C. M., Burr D. H., Silver R. P., Alm R. A., Guerry P. (2001). A phase-variable capsule is involved in virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. Mol. Microbiol. 40 769–777. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickle T. A., Kruger D. H. (1993). Biology of DNA restriction. Microbiol. Rev. 57 434–450. 10.1128/Mmbr.57.2.434-450.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R. E., Levine M. M., Clements M. L., Hughes T. P., Blaser M. J. (1988). Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 157 472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow M. J., Clark T. A., Daum C. G., Deutschbauer A. M., Fomenkov A., Fries R., et al. (2016). The epigenomic landscape of prokaryotes. PLoS Genet. 12:e1005854. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugar G., Herbig A., Forstner K. U., Heidrich N., Reinhardt R., Nieselt K., et al. (2013). High-resolution transcriptome maps reveal strain-specific regulatory features of multiple Campylobacter jejuni isolates. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003495. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facciola A., Riso R., Avventuroso E., Visalli G., Delia S. A., Lagana P. (2017). Campylobacter: from microbiology to prevention. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 58 E79–E92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando U., Biswas D., Allan B., Willson P., Potter A. A. (2007). Influence of Campylobacter jejuni fliA, rpoN and flgK genes on colonization of the chicken gut. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 118 194–200. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francke C., Kormelink T. G., Hagemeijer Y., Overmars L., Sluijter V., Moezelaar R., et al. (2011). Comparative analyses imply that the enigmatic sigma factor 54 is a central controller of the bacterial exterior. BMC Genomics 12:385. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak S., He Y. P., Reed S., Irwin P. (2020). Comparative genomic analysis of a multidrug-resistant Campylobacter jejuni strain YH002 isolated from retail beef liver. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 17 576–584. 10.1089/fpd.2019.2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant C. E., Bailey T. L., Noble W. S. (2011). FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27 1017–1018. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerry P. (2007). Campylobacter flagella: not just for motility. Trends Microbiol. 15 456–461. 10.1016/j.tim.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerry P., Poly F., Riddle M., Maue A. C., Chen Y. H., Monteiro M. A. (2012). Campylobacter polysaccharide capsules: virulence and vaccines. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2:7. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y. P., Yao X. M., Gunther N. W., Xie Y. P., Tu S. I., Shi X. M. (2010). Simultaneous detection and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, and C. lari in chickens using a multiplex real-time PCR assay. Food Anal. Methods 3 321–329. 10.1007/s12161-010-9136-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrixson D. R., Akerley B. J., DiRita V. J. (2001). Transposon mutagenesis of Campylobacter jejuni identifies a bipartite energy taxis system required for motility. Mol. Microbiol. 40 214–224. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K., Fukuda E., Kobayashi I. (2010). Conflicts targeting epigenetic systems and their resolution by cell death: novel concepts for methyl-specific and other restriction systems. DNA Res. 17 325–342. 10.1093/dnares/dsq027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen C. C., Koot J. M., Carrillo C. D., Gannon V. P., Jardine C. M., Mutschall S. K., et al. (2012). An enhanced technique combining pre-enrichment and passive filtration increases the isolation efficiency of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli from water and animal fecal samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 91 506–513. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. S., Li J. Q., Barnes I. H. A., Baltzegar D. A., Pajaniappan M., Cullen T. W., et al. (2008). Role of the Campylobacter jejuni cj1461 DNA methyltransferase in regulating virulence characteristics. J. Bacteriol. 190 6524–6529. 10.1128/Jb.00765-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19 1639–1645. 10.1101/gr.092759.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie S. J., Samson J. E., Moineau S. (2010). Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 317–327. 10.1038/nrmicro2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lertsethtakarn P., Ottemann K. M., Hendrixson D. R. (2011). Motility and chemotaxis in Campylobacter and Helicobacter. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65 389–410. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llarena A. K., Taboada E., Rossi M. (2017). Whole-genome sequencing in epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55 1269–1275. 10.1128/Jcm.00017-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louwen R., Staals R. H., Endtz H. P., van Baarlen P., van der Oost J. (2014). The role of CRISPR-Cas systems in virulence of pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 78 74–88. 10.1128/MMBR.00039-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luangtongkum T., Jeon B., Han J., Plummer P., Logue C. M., Zhang Q. J. (2009). Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiol. 4 189–200. 10.2217/17460913.4.2.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz C., van Vliet A. H. M., Ketley J. M., Penn C. W. (2002). Mutational and transcriptional analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni flagellar biosynthesis gene flhB. Microbiology (Reading) 148(Pt 6) 1679–1685. 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morooka T., Umeda A., Amako K. (1985). Motility as an intestinal colonization factor for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131 1973–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou K. T., Muppirala U. K., Severin A. J., Clark T. A., Boitano M., Plummer P. J. (2015). A comparative analysis of methylome profiles of Campylobacter jejuni sheep abortion isolate and gastroenteric strains using PacBio data. Front. Microbiol. 5:782. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray I. A., Clark T. A., Morgan R. D., Boitano M., Anton B. P., Luong K., et al. (2012). The methylomes of six bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 11450–11462. 10.1093/nar/gks891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachamkin I., Yang X. H., Stern N. J. (1993). Role of Campylobacter jejuni flagella as colonization factors for three-day old chicks: analysis with flagellar mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 1269–1273. 10.1128/Aem.59.5.1269-1273.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin J. L., Eucker T. P., Chavez J. D., Samuelson D. R., Neal-McKinney J., Gourley C. R., et al. (2015). Analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni genome by SMRT DNA sequencing identifies restriction-modification motifs. PLoS One 10:e0118533. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J., Wren B. W., Mungall K., Ketley J. M., Churcher C., Basham D., et al. (2000). The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403 665–668. 10.1038/35001088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A. R., Hall I. M. (2010). BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26 841–842. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads A., Au K. F. (2015). PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 13 278–289. 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. J., Vincze T., Posfai J., Macelis D. (2015). REBASE-a database for DNA restriction and modification: enzymes, genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 D298–D299. 10.1093/nar/gku1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Romero M. A., Cota I., Casadesus J. (2015). DNA methylation in bacteria: from the methyl group to the methylome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 25 9–16. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speegle L., Miller M. E., Backert S., Oyarzabal O. A. (2009). Use of cellulose filters to isolate Campylobacter spp. from naturally contaminated retail broiler meat. J. Food Prot. 72 2592–2596. 10.4315/0362-028x-72.12.2592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukackaite R., Grazulis S., Tamulaitis G., Siksnys V. (2012). The recognition domain of the methyl-specific endonuclease McrBC flips out 5-methylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 7552–7562. 10.1093/nar/gks332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata T., Fujimoto S., Amako K. (1992). Isolation of nonchemotactic mutants of Campylobacter jejuni and their colonization of the mouse intestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 60 3596–3600. 10.1128/Iai.60.9.3596-3600.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Woude M., Braaten B., Low D. (1996). Epigenetic phase variation of the pap operon in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 4 5–9. 10.1016/0966-842x(96)81498-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenaar T. M., Bleuminkpluym N. M. C., Vanderzeijst B. A. M. (1991). Inactivation of Campylobacter jejuni flagellin genes by homologous recombination demonstrates ahat flaA but not flaB is required for invasion. EMBO J. 10 2055–2061. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07736.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020). Campylobacter [Online]. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/campylobacter (accessed July 26, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Zautner A. E., Goldschmidt A. M., Thurmer A., Schuldes J., Bader O., Lugert R., et al. (2015). SMRT sequencing of the Campylobacter coli BfR-CA-9557 genome sequence reveals unique methylation motifs. Bmc Genomics 16:1088. 10.1186/s12864-015-2317-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: GenBank of NCBI with the accession Nos. CP020776 and CP020775.