Summary

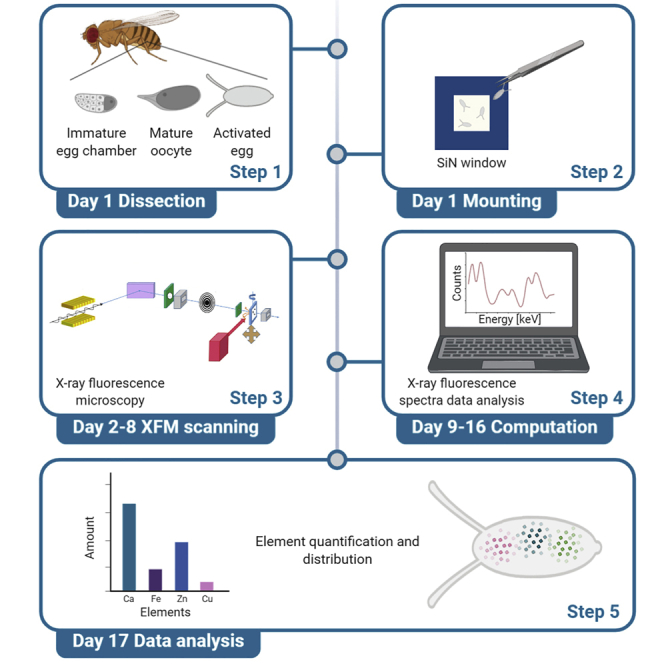

X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) is a powerful tool for mapping and quantifying the spatial distribution of elemental composition of biological samples. Recently, it was reported that transition metal fluctuations occur during Drosophila reproduction, analogous to what is seen in mammals and nematodes, and may contribute to Drosophila female fertility. To further support XFM studies on Drosophila reproduction, we describe procedures for isolating oocytes and activated eggs and examining their elemental composition by XFM scanning and analysis.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Hu et al. (2020).

Subject areas: Biophysics, Metabolism, Microscopy, Model organisms

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Preparing Drosophila oocytes and activated eggs for X-ray fluorescence microscopy scans

-

•

XFM scanning to reveal the elemental contents and distribution of samples

-

•

Analysis and interpretation of XFM data on Drosophila oocyte and egg samples

X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) is a powerful tool for mapping and quantifying the spatial distribution of elemental composition of biological samples. Recently, it was reported that transition metal fluctuations occur during Drosophila reproduction, analogous to what is seen in mammals and nematodes, and may contribute to Drosophila female fertility. To further support XFM studies on Drosophila reproduction, we describe procedures for isolating oocytes and activated eggs and examining their elemental composition by XFM scanning and analysis.

Before you begin

It has been reported in several species that fluctuation of transition elements (e.g., zinc) during oogenesis is essential for reproduction (Duncan et al., 2016; Hester et al., 2017; Mendoza et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). We recently established Drosophila as a model for studying such processes (Hu et al., 2020). Starting with flies of the desired genotype, this protocol involves collecting staged oocytes and laid/activated eggs and mounting and desiccating these on silicon nitride (SiN) windows. These samples are then taken to an X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) facility, where they are scanned for elements of interest, with the results analyzed statistically for metal content. Below we describe the steps in this protocol; further details on its use and execution are in (Hu et al., 2020). Although we describe methods for oocytes and eggs, we expect that they can be extended to examine the elemental content of Drosophila embryos at various stages.

Fly generation

Timing: 2–4 weeks (but with little effort)

-

1.

For collection of oocytes or activated eggs from flies grown under standard conditions, prepare yeast-glucose-agar fly media (10% w/v yeast, 8.9% w/v agar, 10% w/v glucose, 0.05% v/v phosphoric acid, 0.5% v/v propionic acid, 0.27% w/v p-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester, 2.5% v/v ethanol). Food is cooked to melt the agar, mixed, and then poured into glass or plastic vials (or bottles if desired). Vials/bottles are capped with cotton or foam plugs. Food can be refrigerated until needed (though not for many days, or it will start to have condensate on its surface), and is used at room temperature (or any temperature on which the fly stock can grow, 15°C–29°C).

-

2.

For samples that are to be depleted of dietary zinc, the zinc chelator N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridiylmethyl)-1,2-ethylenediamine (TPEN) is added to the medium. A 10 mM stock solution of TPEN in ethanol is made, and appropriate amounts are added to the still-liquid food, and mixed in before the vials/bottles are poured. We used 50 μM and 100 μM as final TPEN concentrations. The same volume of ethanol is added in parallel to the control food.

-

3.

Raise flies of the desired genotype [we used Oregon-R P2 (ORP2), since they are less likely to hold eggs (Allis et al., 1977)]. For sample preparation, collect virgin females and age them in groups of 5 to 10 in a Drosophila vial containing fresh food supplemented with yeast to increase egg production (Derrick et al., 2016; Greenspan, 2004). If the flies are to be deprived of dietary zinc, do not add yeast to the vial to avoid introducing extra zinc. Also collect males of the desired genotypes (we use virgin males), and age them in male-only vials in parallel to the vials of females. No added yeast is necessary for the males.

-

4.

Once the flies are ∼3–5 days old, they are ready for collection of oocytes and eggs.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| N,N,N′,N′-Tetrakis(2-pyridiylmethyl)-1,2-ethylenediamine | Millipore Sigma | 616394 |

| Yeast | MP Biomedics (VWR) | ICN90331280 |

| Agar | Genesee | 66-111 |

| Glucose | LD Carlson | 1992 |

| Grape juice | Walmart | Welch’s |

| Phosphoric acid | VWR | 470302-024 |

| Propionic acid | Sigma | P1386 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma | T9284 |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester | Millipore Sigma | H5501 |

| Ethanol | VWR | 89125-186 |

| Sodium acetate | Fisher | BP333-500 |

| Potassium acetate | Millipore Sigma | 236497 |

| Magnesium chloride | Fisher | BP214-500 |

| Calcium chloride | Fisher | C79-500 |

| Sucrose | Mallinckrodt | 8360 |

| HEPES | Millipore Sigma | H3375 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data | This paper | Available from APS upon request |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Drosophila melanogaster: wild-type strain | Wolfner lab (originally from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) | Oregon-R-P2 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| MAPS | Vogt, 2003 | http://www.stefan.vogt.net/downloads.html |

| Other | ||

| Silicon nitride window | Norcada | NX5200D |

| Window holder aluminum stick | APS custom shop | n/a |

| Aluminum kinematic mounts | APS custom shop | n/a |

| Vortex ME 4 (Hitachi) with an xMap DXP (XIA) readout system | Argonne National Laboratories | https://www.aps.anl.gov/ |

Materials and equipment

-

•

Isolation buffer (IB) (Page and Orr-Weaver, 1997) . Adjusted to pH 7.4 with 5 M NaOH and filter sterilized. Can be stored at 4°C for 6 months.

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| 1 M sodium acetate | 55 mM | 2.75 mL |

| 1 M potassium acetate | 40 mM | 2 mL |

| 100 mM magnesium chloride | 1.2 mM | 0.6 mL |

| 100 mM calcium chloride | 1 mM | 0.5 mL |

| Sucrose | 110 mM | 1.88 g |

| HEPES | 100 mM | 1.19 g |

| ddH2O | n/a | Up to 50 mL |

| Total | n/a | 50 mL |

-

•

Grape juice agar plates. Cook the food to melt it, then cool and pour into plates. Can be stored at 4°C for 1 month, as long as care is taken that it does not dry out.

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Agar | 2.15% (w/v) | 2.15 g |

| Grape juice | 49% (v/v) | 49 mL |

| Phosphoric acid | 0.02% (v/v) | 0.02 mL |

| Propionic acid | 0.2% (v/v) | 0.2 mL |

| ddH2O | n/a | Up to 100 mL |

| Total | n/a | 100 mL |

-

•

Egg wash buffer. Can be stored at room temperature (20°C–25°C) for 6 months.

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride | 0.4% (w/v) | 0.4 g |

| Triton X-100 | 0.03% (v/v) | 0.03 mL |

| ddH2O | n/a | Up to 100 mL |

| Total | n/a | 100 mL |

-

•

Mounting buffer (MB): 400 mM sucrose in ddH2O. Can be stored at 4°C for 6 months.

CRITICAL: Typically, 100 mM ammonium acetate solution is used to rinse extra salts from samples prior to air drying the samples on the SiN windows that are used in XFM experiments. Ammonium acetate is the preferred buffer because its constituents, a weak acid (acetic acid) and base (ammonia), are both volatile; this prevents the buildup of films and microcrystalline salts such as NaCl, KCl, and K2HPO4 that can otherwise form on the sample surface as the sample dries. These elements absorb and scatter X-rays and can confound interpretation of the XFM data. Unfortunately, unactivated Drosophila oocytes lyse in this solution (Q.H. unpublished). Moreover, 100 mM ammonium acetate is hypotonic for Drosophila oocytes, and could therefore activate mature oocytes (Horner and Wolfner, 2008; Page and Orr-Weaver, 1997). Thus, we use 400mM sucrose instead for washing and mounting the samples. The C, H and O atoms present in sucrose present far fewer problems for analyzing XFM data for the heavier elements.

Note: XFM was performed at the 2-ID-E Microprobe at the Advanced Photon Source (APS, Argonne National Laboratory).

Step-by-step method details

Sample isolation

Timing: 2 days

In this step, we isolate the desired samples from flies and prepare them for mounting. It is recommended that sample isolation and mounting be performed on the same day.

Oocytes of the desired stages can be isolated following the protocol below for mounting and scanning. Drosophila oogenesis is categorized into 14 stages. A D. melanogaster ovary contains ∼16 beads-on-a-string structures, called ovarioles. Each ovariole is a “production line” of oocytes, composed of egg chambers of different stages in order (Bastock and St Johnston, 2008; McLaughlin and Bratu, 2015). Oocytes at desired stages can be collected by dissecting ovaries and using morphology to identify oocyte stages. Unlike most other species in which egg activation and fertilization occur simultaneously, Drosophila egg activation is uncoupled from fertilization and is triggered during ovulation (Heifetz et al., 2001; Page and Orr-Weaver, 1997). Drosophila oocytes can be activated in vivo (and collected after being laid) or in vitro by mechanical pressure or swelling (when mature stage-14 oocytes are incubated in appropriate hypotonic solutions (Horner and Wolfner, 2008; Page and Orr-Weaver, 1997)). However, in vitro activation does not completely recapitulate the elemental fluctuations seen in in vivo activation (Hu et al., 2020).

Although we have only scanned oocytes and activated eggs, we expect that an analogous protocol can be used for scanning developing embryos. Embryos of a desired stage (Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein, 1997) can be obtained by collecting laid eggs over a short time-window (30 or 60 min), and then aging them for a controlled period of time. Stages are verified by DAPI-staining a subset of the collected eggs. The embryos may need to be dechorionated manually, in order to allow desiccation.

-

1.Sample isolation

-

a.For oocytes, dissect 3- to 5-day-old virgin females and isolate oocytes of desired stages in isolation buffer (IB) (Page and Orr-Weaver, 1997). A detailed protocol for oocyte isolation can be found in (Derrick et al., 2016), but briefly: using forceps, ovaries are dissected from the females on a microscope slide, and teased apart to release oocytes. Oocytes of the desired stage, based on morphology, are isolated for further processing. It is recommended to isolate >20 oocytes of each desired stage from >4 different females.

-

b.Activated but unfertilized eggs can be collected as the eggs laid by virgin females, but such females normally produce few eggs each day. To be able to collect many eggs during a short time-window in order to prevent any degradation, mate virgin females overnight (14–16 h) with spermless males. These males are the sons of females homozygous for the tudor mutation (Boswell, 1985) that had mated with any genotype of male (we used ORP2 males). On the second day, transfer the female flies to a grape juice agar plate and allow them to lay eggs for ∼5 h at room temperature (20°C–25°C), ideally beginning in the morning. Collect laid eggs by washing them off the plate with egg wash buffer; a small paintbrush can help loosen the eggs. It is recommended to collect >20 activated but unfertilized eggs from >4 different females.

-

a.

-

2.

Wash each egg or oocyte twice by grabbing its dorsal appendages (located at the anterior end, see the position of these in the graphical abstract) with forceps and rinsing it in mounting buffer (MB). Wash immature oocytes by pipetting them up and down in MB with a glass Pasteur pipette. This rinses off external salts from the oocytes/eggs without causing mature oocytes to activate and keeps the treatment of oocytes or eggs at different stages consistent.

CRITICAL: Since immature oocytes are very fragile and mature oocytes can be activated by mechanical pressure (Horner and Wolfner, 2008), it is important to handle the oocytes gently, to avoid the oocytes experiencing external pressure, or damage and loss of elemental content.

-

3.

Accumulate the samples in MB and mount them on the day of collection.

Sample mounting

Timing: 1 day

In this step, we mount the eggs and oocytes that were collected in the previous step onto SiN windows, and wash and air-dry them in preparation for XFM scanning.

-

4.

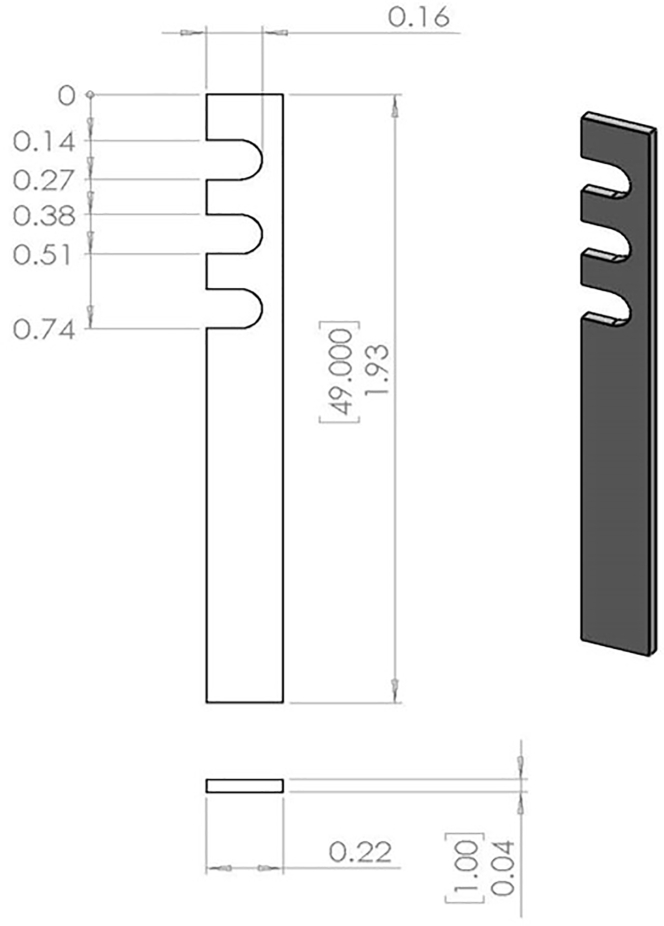

Place a 5 mm × 5 mm SiN window glued to an aluminum stick (APS custom made, see blueprint in Figure 1) with clear nail polish; this is done on the stage of a dissecting microscope. Place a 1 μL drop of MB in the middle of the window. Take extra caution not to contact the window with the pipette tip so as not to break the window.

-

5.

Gently transfer an oocyte or egg to the liquid drop with forceps. Grab the oocyte or egg by the dorsal appendages for ease of manipulation and to avoid pressure on the oocyte body. Take extra care not to contact the window with the forceps. Three or four oocytes or eggs can be mounted on the same window. Blot off extra MB with a Kimwipe touched to the edge of the drop. For immature oocytes without dorsal appendages, mount by pipetting ∼5 μL MB containing the oocytes onto the middle of the window and blotting off the excess MB as described. For each stage examined, prepare 3 to 4 windows for a total of 10 to 15 oocytes.

-

6.

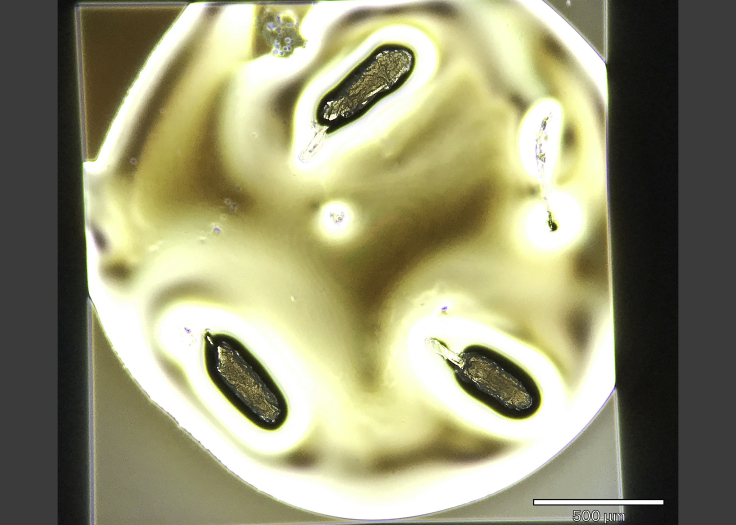

Air-dry the windows by placing them in a closed petri dish (to avoid dust) at room temperature (20°C–25°C) for 30 min. Take a picture of the window under a brightfield microscope (Figure 2) to help locate the samples during future XFM scanning.

-

7.

Windows with samples on them are stored in a closed petri dish. The petri dish can be stored at room temperature (20°C–25°C) in a sealed secondary container with desiccant (e.g., cobalt chloride), until XFM scanning.

Figure 1.

Blueprint of aluminum stick used as the holder of silicon nitride (SiN) windows

Sizes are in inches.

Figure 2.

Representative SiN window with three Drosophila oocytes mounted on it

Note the dorsal appendages, at ~8 o’clock on the upper oocyte, and ~11 o’clock on the lower ones. Scale bar, 500 μm.

XFM data collection and processing

Timing: 2–3 weeks (depending on sample sizes and numbers)

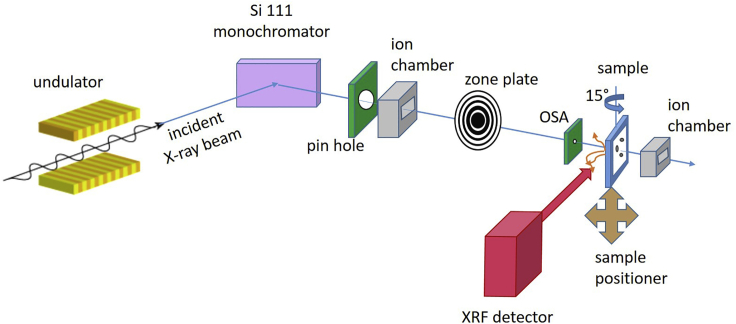

In this step, the mounted specimens are scanned by XFM (Figure 3). Such scanning is available at only a few facilities in the world; we performed it at Argonne National Laboratories. To use the Argonne XFM, one must apply for beamtime in advance; applications are available at https://www.aps.anl.gov/. Other facilities with XFM capacity will have their own protocols.

Figure 3.

Schematic of 2-ID-E hard X-ray microprobe with its essential components (not to scale)

The XRF detector is orthogonal to the incident beam and the sample is rotated 15 degrees toward the detector. At the 2-ID-E beamline, horizontal scans can be done either in fly or step mode, but vertical scans can only be done in step mode; other beamlines may have different scanning modes.

The protocol below follows the general methods for XFM scanning (Fahrni, 2007; Paunesku et al., 2006), but details given here are specific to the Argonne equipment. It is adaptable to the equipment available at other facilities. The scanning is performed with help from expert staff at the facility.

The specimens on SiN windows that are mounted on aluminum sticks (three windows per stick), are fitted into kinematic mounts for Microprobe setup.

-

8.

Mount the samples in chambers filled with He in order to reduce air scatter, decay of X-ray emitted by samples, and signals from Ar (which partially overlap with potassium signals). Set the X-ray beam to 10.3 KeV by using a 3.3 cm undulator and Si 111 monochromator, trimmed by a 500 μm pinhole, focused with a Fresnel zone plate (320 μm /100 nm, Xradia) to a ∼650 μm spot (Thompson and Vaughan, 2001; Wu et al., 2012). The first order is selected by using a 30 μm order-sorting aperture 10 mm upstream of the sample. Scan the sample through the X-ray beam, with a 15° tilt toward the detector, using translation stages with Epics controls (Mooney et al., 2000). X-ray fluorescence spectra are collected by Vortex ME 4 (Hitachi) with an xMap DXP (XIA) readout system (Thompson and Vaughan, 2001). Two ion chambers, upstream of the pinhole and downstream of the sample, measure X-ray absorption by the sample; they are used for normalization.

-

9.

Initially, quickly fly-scan all samples selected for XFM analysis with a large step size (5–10 μm2) and short dwell time (5 ms).

Note: While “fly-scan” seems the perfect term for a Drosophila XFM experiment, it is in fact the standard term for the data collection mode in which the horizontal stage moves the sample continuously through the scan area, at a uniform speed, with fluorescence data collected at specified time intervals (dwell times). This mode is more time-efficient than the more detailed “step scan,” which requires that the stage slow down, stop for data collection, and then resume motion at every pixel position.

CRITICAL: The initial fly-scan is sufficient to detect Zn, K, P, and Fe signals, and allows you to define the area for subsequent more focused detailed scans. It is also necessary to detect any artifacts (sample folds or damage) or contamination by dust or metal particles (which would show up in all elemental maps, or in one elemental map giving extremely high counts). One oocyte/egg scan takes ∼15–20 s.

-

10.

High-resolution fly-scans of selected oocytes are subsequently performed with a 1 μm step size and a 10 ms dwell time; thus each scan takes about 20 min. Altogether, each sample is scanned twice without significant radiation damage or loss of elements.

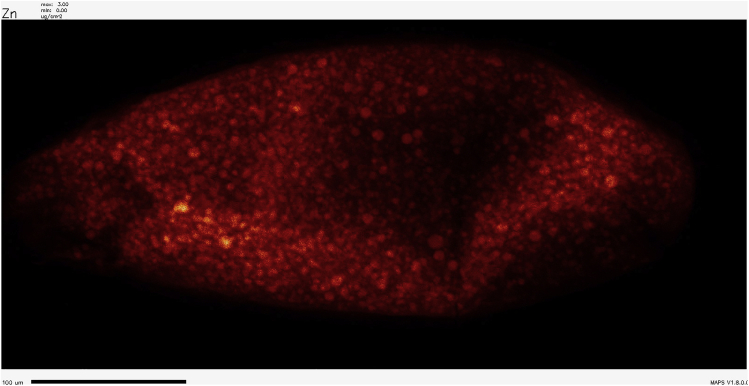

Expected outcomes

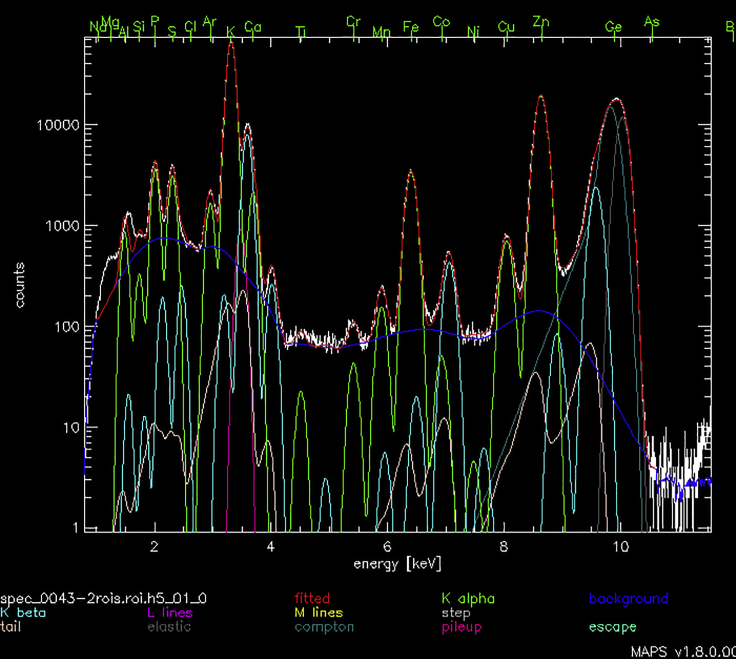

A representative high-resolution scan showing zinc distribution in a Drosophila oocyte is shown in Figure 4. The fitted spectrum of the same scan is shown in Figure 5. In that figure, the counts (plotted on the y-axis) correspond to the number of X-ray photons arriving at the detector; these are plotted as a function of the X-ray emission energy (plotted on the x axis in units of keV). Upon excitation by the synchrotron-generated X-ray beam, each element emits a series of characteristic X-rays whose emission energy corresponds to the elemental symbol along the top of the plot. Within the plot, the white line represents the full spectrum of X-rays collected from a given pixel. The various superimposed colored lines represent simulated data that were obtained by a multiparameter fitting process that takes into account the number of atoms of a given element, the specific X-ray emission energies corresponding to that element, and additional background correction factors.

Figure 4.

Representative XFM scan of a Drosophila oocyte showing the distribution of Zn

Anterior (where the dorsal appendages attach) is to the left (Hu et al., 2020). Scale bar, 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Fitted spectrum showing the amount of elements detected

The fitted spectrum presents the number of photons (y axis) collected by the energy dispersive fluorescence detector as a function of X-ray energy (x axis) showing collected integrated spectrum (white), fitted spectrum (red), background (blue), K-α peaks (green), K-β peaks (turquoise), elastic (grey), and Compton (teal) scattering peaks (Thompson and Vaughan, 2001). K-α peaks (green) and K-β peaks (turquoise) energies are unique for each element. The fitted spectrum is used to quantify the amount of fitted elements in each scanned pixel. From the same oocyte as shown in Figure 4.

Quantification and statistical analysis

It is most efficient to initially process the collected data with the IDL-based software MAPS (Vogt, 2003) to define the regions of interest (ROIs) for each element, focusing analysis on the segment of the X-ray spectrum that corresponds to the emission lines for that element. This quick evaluation allows selection of regions for subsequent high-resolution scans. Full analysis with per-pixel peak fitting (100–500 iterations), peak deconvolution, normalization using downstream ion chamber readings, and calibration, and quantification (Vogt, 2003) are performed by experts at APS using MAPS after the data set and AXO (AXO Dresden, GmBH) standard spectra (Nietzold et al., 2018; Vogt, 2003) were collected. The AXO standard contains Ca, Fe, and Cu for K-line calibration. Its use allows the experimenter to determine the exact peak position for each element and to deconvolute adjacent elemental peaks. Data sets collected in separate runs need to be processed separately, given possible variation in X-ray beam parameters between runs. The processed data sets contain the area concentration of each elements detected.

-

1.

To quantify the amount of Fe, Cu, and Zn in samples, each high-resolution image is cropped into ROIs which include regions chosen manually by drawing boundaries around specific areas in the image using manual tracing with the MAPS ROI tool.

-

2.In our study (Hu et al., 2020), ROIs included:

-

a.background areas (from buffer, substrate and setup)

-

b.egg chambers

-

c.oocytes at different stages

-

d.activated eggs.

-

a.

-

3.

Background levels of elements of interest are accounted for by subtracting the concentrations in background ROIs from the ROIs described above. The area of the background ROI is matched to the area in the ROI of interest using the MAPS tools.

CRITICAL: This removal of background signals removes or minimizes the effect of thickness variation of dried media. MB contains a high concentration of sucrose and can form a layer of gel around the samples after drying, any variation in contamination from sample to sample can thus be subtracted before elemental contents in a given ROI are compared.

-

4.

Multiple data sets were compared using one-way ANOVAs.

Limitations

The use of APS requires application with a tight schedule, which poses limits on available beam time. High-resolution scans usually take a long time, which limits the number of samples that can be scanned and requires careful planning.

The position of the oocytes/eggs on the SiN window is stochastic, and oocytes/eggs can change shape significantly during dehydration on the SiN window. The latter can cause folds or ridges to form, as noted in step 9 (e.g., Figure 2). Although the overall amount of each element detected per oocyte/egg is quite accurate, these distortions during sample preparation can prevent precise calculation of local element concentrations in overlapping biological compartments. It is important to recognize that demarcation of an ROI can be influenced by the experience of the investigator with the anatomy of the sample. Furthermore, investigators need to recognize that interpretation of the ROI can be confounded by the superposition issues. The scanning mode used in this work provides X-ray fluorescence data as a 2D (x, y) projection of the elemental content in the 3D sample. The number of micrograms per square centimeter is a 2D unit but for thin samples like these, all of the atoms in the z-dimension are observed and thus the final processed data account for all of the atoms within the z-dimension as well x and y. For well-defined samples it is sometimes more useful to compare the number of atoms of an element with the ROI by the simple conversion of ug/cm2 units using Avogadro’s number and the ROI area obtained from tools in MAPS software. Regardless of the units, investigators need to consider this caveat when interpreting XFM data. Also, ROIs do not necessarily correspond to biological compartments: when compartments overlie in the z-dimension, the resulting overlaps make it difficult to get precise spatial quantitative analysis. Further treatment of samples (e.g., frozen sections) or tomographic data collection at other beamlines are required for higher resolution of the local distribution of elemental contents.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

A few lines of gap or distortion can appear in images of scanned samples if the beamline is down for maintenance (steps 9 and 10).

Potential solution

If APS loses the beam, an automatic system pauses the scan and resumes it when beam is back online. While this may result in few pixels missing data, the scanned area can be rescanned if desired. In any case, such distortions in the images do not significantly affect elemental quantification or data analysis. Gaps and distortions in the images can also occur even if the beamline remains active during the entire scan. These likely result from positional shifting of samples during the scan, such as if the window holders are not firmly attached to the kinematic mounts, or if samples or apertures are mispositioned. The initial low-resolution scans will detect these data collection problems, which can be remedied by re-collecting the data (after correct alignment of samples, apertures, etc. as needed). This is important because samples with such distortions cannot be used for analysis since they can contain some areas that are unscanned or areas that were scanned multiple times. Finally, processing the data while scanning can identify potentially damaged files, and data can be re-collected for those samples.

Problem 2

For investigators new to Drosophila ovary dissection, rough handling of the oocytes can subject them to mechanical disturbances that could damage, or prematurely activate, the oocytes (steps 1 and 2).

Potential solution

It is recommended to practice dissecting oocytes before mounting them on SiN windows. Moreover, when isolating immature egg chambers and mature oocytes from ovaries, avoid touching the oocytes with the pointy end of forceps. Grab the ovary by the oviduct with one forceps and gently tease off oocytes with the blunt side of another forceps. Discard any oocytes that appear to be leaking contents.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Mariana Wolfner (mariana.wolfner@cornell.edu). Requests for information or advice on XFM analysis should be directed to Olga Antipova and Tom O’Halloran; the former can also provide information on the use of the Argonne facility.

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

MAPS software is available through APS. XFM scanning raw data is stored at APS and can be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. We thank National Institutes of Health grants R01-GM115848 and R01-GM038784 (both to T.V.O.) and R21-HD088744 and R03-HD101732 (to M.F.W.), as well as Cornell’s Graduate School and George P. Hess travel awards (both to Q.H.), a Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellowship, and Barbara Payne Memorial Funds (both to M.F.W.) for funding. We thank Dr. F. Duncan for comments and assistance, N. Buehner for assistance with assembling the Key resources table, and two reviewers for helpful suggestions. The graphical abstract was created with Biorender (www.biorender.com).

Author contributions

Investigation, Q.H. and O.A.A.; Formal Analysis, Q.H., O.A.A., M.F.W., and T.V.O.; Writing – Original Draft, Q.H. and O.A.A.; Writing – Review, Editing, & Additional Text, Q.H., O.A.A., T.V.O., and M.F.W.; Funding Acquisition, T.V.O. and M.F.W.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Allis C.D., Waring G.L., Mahowald A.P. Mass isolation of pole cells from Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. 1977;56:372–381. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastock R., St Johnston D. Drosophila oogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:R1082–R1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell R. tudor, a gene required for assembly of the germ plasm in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell. 1985;43:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega J.A., Hartenstein V. The embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster. 2nd. Springer Science & Business Media; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Derrick C.J., York-Andersen A.H., Weil T.T. Imaging calcium in Drosophila at egg activation. J. Vis. Exp. 2016;114:54311. doi: 10.3791/54311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan F.E., Que E.L., Zhang N., Feinberg E.C., O’Halloran T.V., Woodruff T.K. The zinc spark is an inorganic signature of human egg activation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24737. doi: 10.1038/srep24737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrni C.J. Biological applications of X-ray fluorescence microscopy: exploring the subcellular topography and speciation of transition metals. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan R.J. Second Edition. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004. Fly pushing: the theory and practice of Drosophila genetics. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz Y., Yu J., Wolfner M.F. Ovulation triggers activation of Drosophila oocytes. Dev. Biol. 2001;234:416–424. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester J., Hanna-Rose W., Diaz F. Zinc deficiency reduces fertility in C. elegans hermaphrodites and disrupts oogenesis and meiotic progression. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017;191:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner V.L., Wolfner M.F. Mechanical stimulation by osmotic and hydrostatic pressure activates Drosophila oocytes in vitro in a calcium-dependent manner. Dev. Biol. 2008;316:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Duncan F.E., Nowakowski A.B., Antipova O.A., Woodruff T.K., O’Halloran T.V., Wolfner M.F. Zinc dynamics during Drosophila oocyte maturation and egg activation. IScience. 2020;23:101275. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J.M., Bratu D.P. Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis: an overview. In: Bratu D.P., McNeil G.P., editors. Drosophila Oogenesis: Methods and Protocols. Springer; 2015. pp. 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza A.D., Woodruff T.K., Wignall S.M., O’Halloran T.V. Zinc availability during germline development impacts embryo viability in Caenorhabditis elegans. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017;191:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney T.M., Arnold N.D., Boucher E., Cha B.K., Goetze K.A., Kraimer M.R., Rivers M.L., Sluiter R.L., Sullivan J.P., Wallis D.B. EPICS and its role in data acquisition and beamline control. AIP Conf. Proc. 2000;521:322–327. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzold T., West B.M., Stuckelberger M., Lai B., Vogt S., Bertoni M.I. Quantifying X-Ray fluorescence data using MAPS. J. Vis. Exp. 2018;132:e56042. doi: 10.3791/56042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A.W., Orr-Weaver T.L. Activation of the meiotic divisions in Drosophila oocytes. Dev. Biol. 1997;183:195–207. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paunesku T., Vogt S., Maser J., Lai B., Woloschak G. X-ray fluorescence microprobe imaging in biology and medicine. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006;99:1489–1502. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A.C., Vaughan D. vol. 8. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, University of California; 2001. (X-ray data booklet). [Google Scholar]

- Vogt S. MAPS: A set of software tools for analysis and visualization of 3D X-ray fluorescence data sets. J. Phys IV France. 2003;104:635–638. [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.-R., Hwu Y., Margaritondo G. Hard-X-ray zone plates: recent progress. Materials. 2012;5:1752–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Duncan F.E., Que E.L., O’Halloran T.V., Woodruff T.K., O’Halloran T.V., Woodruff T.K. The fertilization-induced zinc spark is a novel biomarker of mouse embryo quality and early development. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22772. doi: 10.1038/srep22772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

MAPS software is available through APS. XFM scanning raw data is stored at APS and can be available upon request.