Abstract

Formaldehyde (FA) exposure has been proven to increase the risk of asthma and cancer. This study aimed to evaluate for 28 days the FA inhalation effects on oxidative stress, inflammation process, genotoxicity, and global DNA methylation in mice as well as to investigate the potential protective effects of melatonin. For that, analyses were performed on lung, liver and kidney tissues, blood, and bone marrow. Bronchoalveolar lavage was used to measure inflammatory parameters. Lipid peroxidation (TBARS), protein carbonyl (PCO), non-protein thiols (NPSH), catalase activity (CAT), comet assay, micronuclei (MN), and global methylation were determined. The exposure to 5-ppm FA resulted in oxidative damage to the lung, presenting a significant increase in TBARS and NO levels and a decrease in NPSH levels, besides an increase in inflammatory cells recruited for bronchoalveolar lavage. Likewise, in the liver tissue, the exposure to 5-ppm FA increased TBARS and PCO levels and decreased NPSH levels. In addition, FA significantly induced DNA damage, evidenced by the increase of % tail moment and MN frequency. The pretreatment of mice exposed to FA applying melatonin improved inflammatory and oxidative damage in lung and liver tissues and attenuated MN formation in bone marrow cells. The pulmonary histological study reinforced the results observed in biochemical parameters, demonstrating the potential beneficial role of melatonin. Therefore, our results demonstrated that FA exposure with repeated doses might induce oxidative damage, inflammatory, and genotoxic effects, and melatonin minimized the toxic effects caused by FA inhalation in mice.

Keywords: pollutant, xenobiotic, oxidative damage, inflammation, toxicology

Introduction

Formaldehyde (FA) is a contaminant air pollutant and a compound of particular concern due to its ubiquitous distribution as it is produced in many industries and has an extensive and versatile range of use. Thus, millions of people worldwide are exposed to this compound [1–3]. In medicine, FA is used in anatomy and pathology laboratories and embalming, for its sterilizing, preserving, and stabilizing properties [4]. In industry, FA is widely used in the production of several products such as resins, adhesives, binders for plywood, plastics, synthetic fibers, paints, and insulation foams, which are raw materials employed in furniture, upholstery, carpeting, drapery, and other household products, due to that many workers are occupationally exposed to FA [5–7].

International agencies such as the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, and Occupational Safety and Health Administration suggest limits of 0.016, 0.3, and 0.75 ppm per 8 hours of work, respectively [8–10], while the World Health Organization recommends an internal FA limit of 0.08 ppm (0.1 mg/m3) [11]. Nevertheless, toxicological studies demonstrated that airborne FA levels often exceed recommended exposure limits [12–14].

The primary effects of acute exposure to FA are irritation of the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract and the eyes, site of first contact [15]. However, it also affects metabolism in many different organs, since it is present in all cells of the human body [16]. Due to the fact that FA has high solubility and reactivity with nucleophilic groups of proteins and nucleic acids, it is able to form adducts and induce DNA damage [6, 17]. This characteristic explains the toxic and carcinogenic properties of formaldehyde [2, 18]. Based on genotoxic and carcinogenic effects, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified this substance as a human carcinogen [19].

Damage to organ tissue from FA may be associated with oxidative stress and inflammation [20]. Recently, some studies demonstrated that FA inhalation increases the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROSs), and it causes a disruption of the physiological balance between oxidant and antioxidant enzymes in the lung tissue of rodents [7, 21]. ROSs are cytotoxic agents causing oxidative damage by attacking cell membrane and DNA and can contribute to a variety of diseases [22, 23]. Mechanisms of cellular defense can regulate oxidative stress through glutathione (GSH) and enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase (CAT) [24].

Many studies have reported that antioxidant treatment can prevent oxidative stress in the tissues [7, 22, 25, 26]. Melatonin, an endogenous neurohormone produced by the pineal gland, acts on many physiological functions, including biological regulation of circadian rhythms, sleep, reproduction, and neuroimmunomodulation [27, 28] mainly through the activation of two G-protein-coupled plasma membrane receptors: MT1 and MT2 [27, 29]. It is small molecular size and its amphiphilic properties facilitate melatonin’s penetration into subcellular compartments [30]. Melatonin protection actions have been previously reported against various xenobiotics [31–35], including the FA exposure [36–39]. Thus, melatonin and its metabolites play an important protective role in different pathophysiological conditions by attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation [32]. Melatonin neutralizes a host of toxic reactive molecules directly, stimulates the synthesis and the activation of antioxidant enzymes, and also inhibits pro-oxidative enzymes [28, 32, 40].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate for 28 days the FA inhalation effects on oxidative stress, inflammation process, and genotoxicity in mice as well to investigate the potential protective effects of melatonin administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) on reduction these parameters. For that, oxidative damage was assessed by levels of substances reactive to thiobarbituric acid (TBARS) and carbonylated proteins (PCO) beyond to antioxidant defenses such as levels of non-protein thiols (NPSH) and catalase activity (CAT) on lung, liver, and kidney tissues. Histological analysis of the lung was performed and bronchooalveolar lavage (BAL) was used to measure the levels of nitric oxide (NO) and inflammatory parameters. The comet assay, micronucleus test, and global DNA methylation were also assessed. To our knowledge, there are neither studies on the investigation of the melatonin influence (20 mg/kg; i.p.) to prevent oxidative damage induced by the FA inhalation exposure nor studies about the association between exposure to FA and global DNA methylation on mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male adult Swiss mice (30–45 g) were kept in a temperature-controlled (22 ± 2°C) under a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to water and food. The experiments were performed in accordance with national and international legislation (Guidelines of the Brazilian Council for Animal Experimentation—CONCEA and the US Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals). The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Federal University of Santa Maria (process #4738290818).

Chemicals

Formaldehyde (HCHO) was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Melatonin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical quality and obtained from standard commercial suppliers. Melatonin was dissolved in saline solution (0.9%) containing 5% ethanol.

Experimental design and FA exposure

An inhalation chamber with 16 L (32 cm × 25 cm × 20 cm) coupled to a nebulizer (Inalamax NS®, Brazil) was used to generate an air stream from an aqueous FA solution. Ambient concentrations of FA within the chamber were determined using an Umex-100 passive sampler (SKC Inc., Eighty Four, USA), and FA analysis on the sampler was performed by gas chromatography in accordance with ISO 16000-4- 2004.

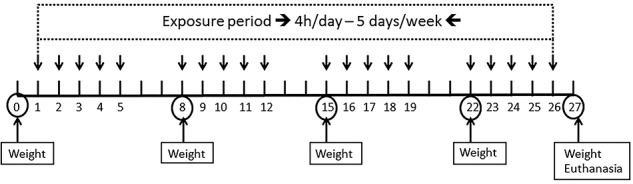

The animals were randomly divided into nine experimental groups with seven animals in each and then subdivided into two experiments. For the Experiment 1, the animals received inhalation of FA or their vehicle: Control Group (animals received FA vehicle); Group 0.5 ppm (animals received FA 0.5 ppm); Group 1 ppm (animals received FA 1.0 ppm); Group 5 ppm (animals received FA 5.0 ppm); and Group 10 ppm (animals received FA 10.0 ppm). For the Experiment 2, the animals received melatonin (20 mg/kg—i.p.) or their vehicle (i.p.) and 30 min after injection received inhalation of FA or their vehicle: Control Group (animals received melatonin vehicle + FA vehicle); Group 5 ppm (animals received melatonin vehicle + FA 5.0 ppm); Group Mel (animals received melatonin + FA 5.0 ppm); and Group 5 ppm + Mel: animals received melatonin + FA 5.0 ppm). Inhalations were performed 4 h per day, 5 times a week for 4 weeks, according to the OECD Test 412 [41] (Fig. 1). FA doses used in this study were chosen based on occupational exposure studies and reviews [42–46]. Regarding the melatonin dose, it was selected based on previous studies, indicating the nephroprotective activity observed in mice [32], in addition to the cardioprotective effect in rats [31]. After 24 h of the last FA exposure, the animals were euthanized with xylazine and ketamine (i.p.). Blood was collected directly from the heart ventricle. Subsequently, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was collected and liver, kidneys, lungs, and femurs were removed. Tissue samples were homogenized in Tris/HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4 (1/10, w/v), and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were separated and used for biochemical analysis. Total protein quantification was performed by the method described by Bradford [47] using bovine serum albumin as standard.

Figure 1.

Experimental design.

Collection and analysis of BAL

After euthanasia, the thorax of each animal was opened; the trachea was cannulated and perfused with 1 mL of PBS. The wash solution was collected, kept on ice until the end of the procedure to prevent cell lysis, and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min. The total cell number was determined in a Neubauer chamber using trypan blue staining. Giemsa stained slides were made for differential cell counting. The supernatant was used for the measurement of nitric oxide (NO) levels by the Griess method adapted to the Cobas Mira® automated system (Roche Diagnostics) according to Tatsch et al. [48] and the results expressed in μmol/L.

Biochemical marker

To assess liver toxicity, we determined the plasma activity of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) spectrophotometrically using Bioclin® kits according to manufacturer’s specifications (Bioclin, Brazil).

Oxidative damage markers

Lipid peroxidation

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content, a measure of lipid peroxidation, was determined by testing the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) described by Buege and Aust [49]. To this end, 250 μL of tissue homogenates were incubated in a 100°C water bath with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) 10% and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) 0.6% for 15 min. They were then cooled on ice, added n-butanol, vortexed vigorously, and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used for absorbance reading in a spectrophotometer at 535 nm. Results were expressed in nmol TBARS/g tissue.

Carbonyl protein

Oxidative damage to proteins was evaluated by determining the carbonyl groups based on the reaction with dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) according to the method described by Levine [50]. Briefly, proteins were precipitated by the addition of TCA 10%, redissolved in DNPH, and absorbance was read at 370 nm. Results were calculated using the extinction coefficient of 22 000 for aliphatic hydrazone. Results were expressed as nmol carbonyl protein/g tissue.

Non-enzymatic antioxidant defenses

Non-protein thiols

The levels of NPSH were assessed according to Ellman [51]. An aliquot of the homogenate was diluted with TCA 10% for protein precipitation and centrifuged. The deproteinized supernatant was incubated with potassium phosphate buffer (TFK 1 M pH 7.4), and 5,5 dithio-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) at room temperature. The developed yellow color was read immediately at 412 nm. Results were expressed as μM NPSH/mg protein.

Ferric Antioxidant Power Test

Ferric Antioxidant Power Test (FRAP) was determined according to the Benzie and Strain method [52]. The assay measures the ability of antioxidants to reduce the [Fe (TPTZ)2]3+ complex to the blue [Fe (TPTZ)2]2+ complex. Plasma was added to FRAP reagent (TPTZ 10 mM and FeCl3 20 mM in acetate buffer 300 mM, pH 3.6), and absorbance was measured at 593 nm. Ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) was used as a standard. The antioxidant capacity of the samples was expressed in μMol Fe2+/ml of plasma and was calculated by interpolating the absorbance values on the calibration curve.

Enzyme antioxidant defense

Catalase activity

CAT enzyme activity was determined according to Aebi [53]. Briefly, the reduction in the absorbance of a reaction mixture containing 30 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was measured at 240 nm for 90 s with a spectrophotometer. Results were expressed as CAT enzyme activity (IU/mg protein).

Genotoxicity

Comet assay

The alkaline comet assay is used for the detection of DNA strand breaks in cells or nuclei isolated from various tissues that have been exposed to potentially genotoxic materials. Five microliters of heparinized whole blood were added to 95 μL of low melting agarose (0.75%). The mixture was spread on a slide coated with a normal melting (1.5%) agarose layer, covered with a coverslip, and stored at 4°C to solidify. After 2 h, the coverslip was removed and the slides were placed in a lysis solution (NaCl 2.5 M, EDTA 100 mM, Tris–HCl 10 mM, distilled water, DMSO 10%, and Triton X-100 1%) overnight. Subsequently, slides were incubated in an alkaline buffer (NaOH 300 mM and EDTA 1 mM, pH 13) and acclimatized for 20 min. The DNA was electrophoresed for 20 min at 25 V and 300 mA, and the buffer was neutralized with 0.4 M Tris (pH 7.5) for 15 min in the dark, dry, fixed in ethanol 96% for 5 min. After drying, the nucleoids were stained with ethidium bromide and examined at ×500 magnification under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX-71, Japan). Random images of 100 cells (50 cells from each of the two replicate slides) were analyzed from each animal. The damage score is based on tail moment and tail DNA amount and is considered a sensitive measure of DNA damage [54]. Cell quantification was performed using mean tail moments and DNA tail using free CometScore™ software.

Micronucleus test

Both femurs of each mouse were dissected, the epiphyses were cut, and the bone marrow was removed with a syringe containing a needle. The marrow was diluted in fetal bovine serum. Centrifugations and cell suspension were spread on slides and stained with MayGrunwald stain for 7 min, washed with water, and stained with Giemsa stain (diluted 1/10 with distilled water) for 1 min. The slides were washed with water and dried at room temperature. Polychromatic erythrocytes (immature erythrocytes) were stained light blue and normochromatic erythrocytes (mature erythrocytes without ribosome) were stained red-tiled. After staining, the slides were analyzed by light microscopy. The presence or absence of micronuclei (MN) was observed through the formation of small points near the cell nucleus. One thousand cells were counted for each sample in duplicates. Results were expressed as MN frequency per 1000 cells [54].

Global methylation

The DNA extraction from liver tissue was based on a method established by Lahiri and Numberger [55]. After the DNA extraction, the amount of DNA was quantified by a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and diluted to 2 μg of DNA in each sample. The samples treatment was based on established methods [56, 57]. After the treatment, the samples were centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 5 min and 70 μL of the supernatant were injected in high-pressure liquid chromatography with diode array detection according to an established method by Barbosa et al. [5]. The relative content of 5-methyl-deoxy-cytidine (5mdC) was expressed as a percentage in respect to the total amount of deoxycytidine (dC) and was calculated according as Global DNA methylation (%) = [5mdC/(dC + 5mdC)] × 100.

Histopathological evaluations

After collecting the blood, the mice were euthanized under anesthesia and complete macroscopic evaluation of all body cavities was conducted. For histological analysis, the lungs were removed and immersed in buffered formalin fixative solution. Subsequently, 5-μm-thick sections were prepared from paraffin-embedded slices and then stained with Masson-Goldner [58]. Stained slides were photographed using Zeiss AX10 microscopy (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyzes were performed using the GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Results were compared using one-way analysis of variance, followed by post hoc tests for multiple comparisons (Newman–Keuls test) and expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between groups were considered significant when P-values were less than 0.05 (P < 0.05).

Results

Effect of FA and melatonin in the animals’ weight

There were no significant changes in animals’ weight in any group (data not shown).

Determination of FA concentration

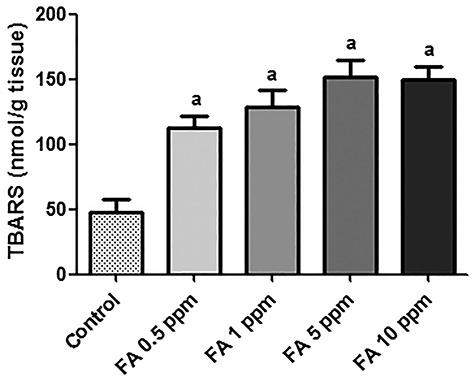

Inhalation exposures with different FA concentrations were performed (0.5, 1, 5, and 10 ppm). Based on this experiment, it was observed that TBARS levels in the liver of mice exposed to the mentioned concentrations happens in a dose-dependent way (Fig. 2). It was observed significant differences among the groups exposed to FA. This way, as the highest FA concentrations (5 and 10 ppm), there was no difference in relation to hepatic TBARS levels, so we chose the 5 ppm concentration to continue the FA exposure experiments with melatonin.

Figure 2.

Level of lipid peroxidation in the liver of mice exposed to FA in different concentrations (n = 7). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. aSignificant difference in relation to the control group (P < 0.0001).

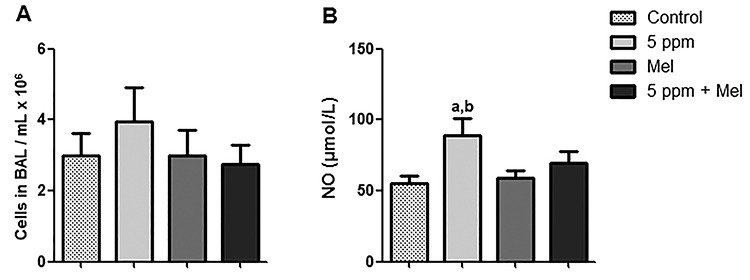

Effect of FA and melatonin in the BAL

The results showed that 5-ppm FA induced an increase in the number of cells in BAL, but this increase was not significant in relation to other groups (P > 0.05). In addition, it was observed that the percentage of lymphocytes and monocytes did not significantly differ among groups (data not shown). Besides, it was possible to observe that the 5 ppm + Mel group had a decreased number of cells in BAL; however, this decrease did not show any significant difference in relation to other groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3A). It was quantified the NO levels in the BAL supernatant. Figure 3B shows that the exposition to 5-ppm FA (89.33 ± 11.79 μmol/L) increased NO levels in comparison to the control group (55.60 ± 5.20 μmol/L) and to Mel group (59.00 ± 5.51 μmol/L) (P < 0.05). Melatonin reduced NO levels in the 5 ppm + Mel group (69.60 ± 8.23 μmol/L) when compared with the 5-ppm group; therefore, this reduction had no significant difference (P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of FA and melatonin in BAL. (A) Inflammatory cells in BAL of mice. (B) NOx levels in BAL of mice. Values expressed as mean ± SEM. aSignificant difference in relation to the control group (P < 0.05); bSignificant difference in relation to Mel group (P < 0.05).

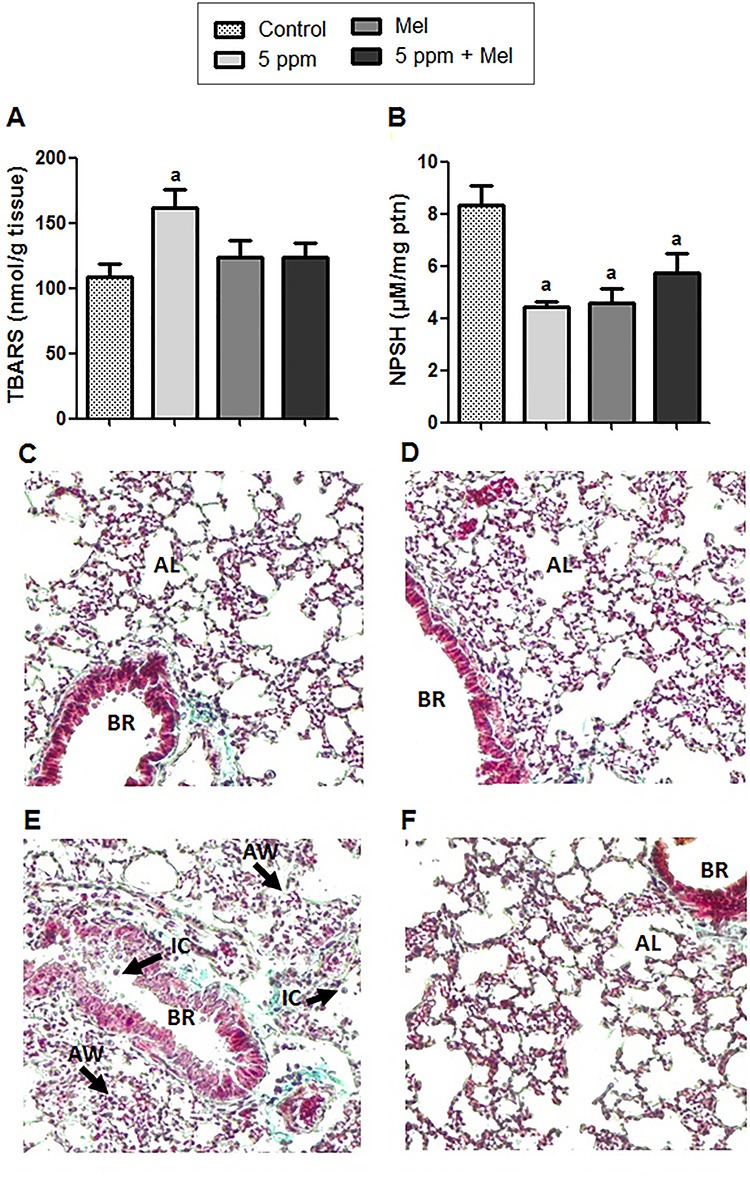

Effect of FA and melatonin in lung tissue

According to data shown in Fig. 4A, TBARS levels in the lung were significantly higher in the group exposed to 5 ppm FA (161.6 ± 14.21 nmol/g tissue) in relation to the control group (108.5 ± 9.85 nmol/g tissue) (P < 0.05). The 5 ppm + Mel group showed a decrease in TBARS levels (123.7 ± 11.32 nmol/g tissue); however, this effect did not present significant difference in comparison to 5 ppm FA group (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of FA and melatonin in lung tissue. (A) TBARS levels. (B) Levels of non-protein thiols (NPSH). (C–F) Histology of control groups, Mel, 5 ppm and 5 ppm + Mel, respectively; 10x. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. aSignificant difference in comparison to the control group (P < 0.05); BR represents the bronchioles; IC represents inflammatory cells; AW represents the thickening of alveolar wall; AL represents the alveolar lumen.

Regarding NPSH levels in lung tissue, the exposition to 5-ppm FA decreased this marker (4.44 ± 0.2 μM/mg ptn) when compared with the control group (8.34 ± 0.74 μM/mg ptn) (P < 0.01). In the 5 ppm + Mel group, although no significant, NPSH levels presented an increase (5.75 ± 0.71 μM/mg ptn) when compared with 5-ppm FA group; however, it did not reestablish the control group levels (Fig. 4B). Besides this, histological analysis (Fig. 4C–F) showed damage to the lung tissue observed in the thickening of alveolar walls and consequent decrease in alveolar lumen plus an increase in the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the 5-ppm group. In the 5 ppm + Mel group, these damages were reduced.

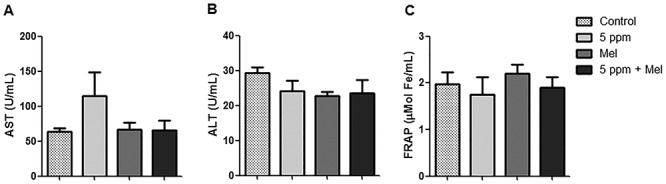

Effect of FA and melatonin in plasma of mice

It was observed that AST activity, determined in plasma, increased in the 5-ppm group; however, there was no significant difference among groups (P > 0.05). In addition, animals in the 5 ppm + Mel group had similar AST levels to the control group and Mel group (Fig. 5A). The ALT activity did not show significant difference among groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of FA and melatonin in plasma of mice. (A) AST activity. (B) ALT activity. (C) FRAP. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. There were no significant differences among groups.

Figure 5C shows the plasma antioxidant capacity measured through the FRAP reducing power. It was observed that, although the exposure to 5-ppm FA induced a decrease in FRAP levels and the pretreatment with melatonin increased this measure, no significant difference was observed. Besides, the group treated only with melatonin presented higher antioxidant power when compared with other groups.

Effect of FA and melatonin in hepatic and renal tissues

Table 1 shows the oxidative stress markers in hepatic and renal tissues. Regarding the liver, it was observed that 5-ppm FA exposition promoted a significant increase in TBARS (P < 0.0001) and PCO (P < 0.05) levels when compared with the control group. In addition, melatonin decreased TBARS (P < 0.05) and PCO (P < 0.01) levels in the 5 ppm + Mel group with the last parameter being almost restored to the levels presented in the control group. Regarding TBARS and PCO levels in the kidney, it was observed a small decrease in the 5-ppm FA group in relation to the control group and an increase in the 5 ppm + Mel group in relation to the 5-ppm FA group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of FA and melatonin in oxidative stress parameters in mice

| aa | Groups | TBARs nmol/g tissue | PCO nmol/g tissue | NPSH μM/mg protein | CAT μmol/mg protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Control | 40.84 ± 7.80 | 1.89 ± 0.15 | 30.46 ± 4.53 | 25.68 ± 3.85 |

| 5 ppm | 152.1 ± 13.00a,b | 3.25 ± 0.31a,b | 15.28 ± 3.25a | 22.24 ± 1.09 | |

| Mel | 64.26 ± 11.56 | 1.86 ± 0.52 | 19.21 ± 2.93a | 21.48 ± 2.15 | |

| 5 ppm + Mel | 112.5 ± 12.34a,b,c | 1.97 ± 0.23c | 12.97 ± 2.35a | 21.17 ± 2.05 | |

| Kidney | Control | 191.0 ± 10.30 | 3.71 ± 0.37 | 16.90 ± 1.56 | 25.17 ± 2.22 |

| 5 ppm | 182.2 ± 12.32 | 2.11 ± 0.41a | 11.41 ± 2.76 | 22.39 ± 2.31 | |

| Mel | 176.6 ± 13.29 | 3.11 ± 0.43 | 16.86 ± 1.37 | 23.20 ± 2.98 | |

| 5 ppm + Mel | 190.5 ± 12.33 | 1.75 ± 0.49a | 9.26 ± 0.29a,b | 24.44 ± 1.71 |

Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

aSignificant difference in relation to the control group.

bSignificant difference in relation Mel group.

cSignificant difference in relation 5 ppm group; differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Considering the NPSH levels, the exposition to 5-ppm FA caused a decrease in NPSH levels in the liver and kidney when compared with the control group. Such difference was only significant in the liver. The pretreatment with melatonin failed to reverse the NPSH in both tissues (Table 1). No significant change was observed among the treated groups in relation to CAT enzyme activity; however, the exposure to 5-ppm FA decreased the activity of this enzyme in both liver and kidney and the pretreatment with melatonin increased its activity in the kidney (Table 1).

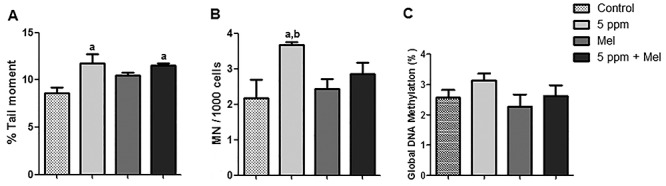

Effect of FA and melatonin in genotoxicity

In comet assay, the DNA strand break in the cells was expressed in the tail moment. According to Fig. 6A, the results showed that the exposition to 5-ppm FA significantly increased the magnitude of the DNA strand break when compared with the control group (P < 0.01). However, melatonin was unable to protect this DNA damage. Observing the MN frequency in bone marrow cells, a significant increase was seen in the 5-ppm FA group when compared with the control group (P < 0.05). Melatonin was able to prevent MN formation in bone marrow cells of the animals exposed to 5-ppm FA, but this reduction in MN frequency was not significant (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

DNA damage. (A) Comet assay. (B) Micronucleus. (C) Global DNA methylation. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. aSignificant difference in relation to the control group (P < 0.05); bSignificant difference in relation to Mel group (P < 0.05).

Global DNA methylation

Regarding the global DNA methylation (Fig. 6C) was observed that the global DNA methylation levels increased in the 5-ppm group. However, there was no significant difference among groups (P > 0.05). The global DNA methylation levels were 2.56, 3.12, 2.26, and 2.61% for control, 5 ppm FA, Mel, and 5 ppm + Mel, respectively. In the 5 ppm + Mel group, the global DNA methylation showed a decreased when compared with 5-ppm FA group; however, this reduction was not significant (P > 0.05).

Discussion

It is known that FA is a substance that causes toxicity not only in the upper respiratory tract [59] but also in several organs as lung [60], liver [25], and kidney [61]. The concentration of 5-ppm FA was chosen based on experiment 1, which showed that TBARS levels in the liver of mice exposed to different FA concentrations happens in a dose-dependent way (Fig. 2). Besides, 5 and 10 ppm did not differ in the observed effect, justifying the use of 5 ppm concentration to perform the experiments with melatonin. Regarding the melatonin dose applied in this study, it was based on recent studies where nephroprotective activity was observed in mice [32], in addition to the cardioprotective effect in rats [31]. To our knowledge, there are no studies on melatonin influence (20 mg/kg; i.p.) to prevent oxidative damage induced by the FA inhalation exposure associated with epigenetic studies on mice.

In this study, it was evaluated the FA effects on different parameters as oxidative stress, inflammation, and genotoxicity, as well as the melatonin activity to prevent the damage caused by the inhalation exposure to 5-ppm FA. The main results showed that the inhalation exposure to 5-ppm FA caused an increase in NO levels and inflammatory cells recruited for BAL. Besides, the pretreatment with melatonin reduced both parameters. Oxidative stress in the lung was evident and characterized by an increase in TBARS levels and a decrease in NPSH levels in animals exposed to 5-ppm FA. It was observed that the pretreatment with melatonin before inhaling FA decreased TBARS levels and increased NPSH levels. Regarding DNA damage, it was observed that melatonin decreased MN formation in bone marrow cells in animals exposed to FA. Thus, it was demonstrated that FA triggered oxidative damage in lungs and liver of mice and such damage may be prevented with melatonin administration. Studies show that FA inhalation exposure induces airway inflammation [24, 62, 63]. In this context, it was evaluated the presence of inflammatory cells in the lung parenchyma of mice submitted to FA exposure and to the treatment with melatonin analyzing the total and differential counts of inflammatory cells in BAL.

Results showed a higher number of cells recruited for BAL in mice exposed to FA; however, there was no significant difference. In agreement with the results found in this study, Fujimaki et al. [64] investigated the effects of FA exposure in low concentrations (40, 80, and 2000 ppb for 12 weeks) on the inflammatory response in mice. It was demonstrated that FA exposure did not cause an increase in inflammatory cells in BAL. Another study, carried out by Maiellaro et al. [65], also found no difference in the number of cells recruited for BAL among pregnant rats exposed to 0.75-ppm FA for 21 days. In contrast to what was observed in BAL cells, other authors demonstrated an increase in inflammatory cells in lungs of rats exposed to FA associated with an increase in macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils [24, 60]. In both studies, the used FA concentrations were higher (1, 5, and 10% for 5 days) when compared with those used in this study. In addition, the increase in the number of BAL leukocytes from rats exposed to FA can occur in a time-dependent way as shown by the study of Lino dos Santos Franco et al. [66]. This way, the first line of defense against harmful agents is the mobilization of leukocytes, which migrate to the inflammatory site through the endothelial cell barrier. Thus, mice exposed to FA 5 ppm to inhalation exposure for 28 days showed a modest inflammatory response.

It is known that NO is a modulator of the leukocyte-endothelial cell interaction, controlling leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium during the inflammatory process [67]. In addition, NO can be eliminated by ROS to form the peroxynitrite anion, which can cause oxidative damage and it also play a role in airway inflammation [23, 24, 68]. Our results showed an increase in NO levels in BAL due to the exposure to FA. Our findings according to Lino dos Santos Franco et al. [67] who observed an exacerbated release of nitrites by BAL cells in rats exposed to 1% FA for 3 days. Likewise, mice exposed for 90 days to a mixture of volatile organic compounds had increased NO levels in the lung, as observed by Wang et al. [23]. Based on these reported studies, FA has the potential to cause irritation and injury to the lung parenchyma, triggering an inflammatory process in a non-specific manner.

This study showed that FA increased the cellular inflow in the lung, what was evidenced by the increase in NO levels and the leukocytes amount in BAL. Additionally, it was observed in the differential count that the leukocytes recruited in the lung were composed of mononuclear cells. Regarding lung histology, it was observed an increase in the infiltration of inflammatory cells and a thickening of the airway walls with visible remodeling of the airways probably due to the oxidative damage induced by FA exposure. According to our findings, Murta et al. [60] reported an increase in the inflammatory response plus an increase in the area of the alveolar lumen and a decrease in density of the volume of alveolar septa. These same results were supported by Liu et al. [69] that found the same effects cause by FA inhaling exposure.

Oxidative stress occurs in the cell when the production of oxidants is greater than the ability to remove them by endogenous antioxidants. The produced ROS react with several biological macromolecules, including membrane lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, changing their functions [70–72]. Oxidative stress is considered one of the potential mechanisms behind FA-induced systemic toxicity [25, 60, 73–75]. In this sense, to evaluate the effect of melatonin on the damage caused by FA exposure, some important biomarkers of oxidative stress in the pulmonary, hepatic, and renal tissues were evaluated.

In the present study, mice exposed to 5-ppm FA presented elevated levels of TBARS in lung and liver, while elevated levels of PCO were found in the liver. TBARS is an indicator of lipid peroxidation, a result from the reaction of ROS with phospholipids present in biological membranes, and PCO formation, on the other hand, is the reaction of ROS with proteins [76, 77], indicating that lipid and protein damage were induced in these tissues. The results are in line with previous studies where high levels of lipid peroxidation and PCO were observed in different rodent tissues [22, 60, 75, 78, 79].

When oxidative stress occurs, cells try to neutralize oxidative effects and restore redox balance, activating or silencing genes that encode defensive enzymes, transcription factors, and structural proteins [70]. The antioxidant defense system operates through enzymatic and non-enzymatic components [22]. Considering this, CAT activity was evaluated together with non-enzymatic antioxidants such as NPSH levels in tissues and FRAP in plasma. There were no significant changes in CAT activity in the liver and kidney exposed to FA. According to our findings, Ramos et al. [79] did not observe significant changes in CAT in the renal tissue of Fisher rats exposed to FA at 1, 5, and 10% for 5 days. Similarly, Lino dos Santos Franco et al. [24] showed no difference in CAT activity in the lung of Wistar rats after 3 days of exposure to 1% FA.

Regarding NPSH levels, results showed that FA exposure triggered a decrease in this marker in the liver, kidney, and lung. This result is corroborated by Brandão et al. [80] that found an NPSH levels decrease in testicles of mice exposed to cadmium chloride. GSH, the main NPSH in tissues, acts as a free radical scavenger, helps in the regeneration of other antioxidants [80], and plays a vital role as a coenzyme in the detoxification of many chemicals, including FA [71, 81]. This way, FA exposure may have depleted GSH in cells. This was observed by a decreasing in NPSH levels in lung and liver, interrupting the balance between oxidants and antioxidants and causing oxidative stress, which was observed by the increase in TBARS and PCO in these tissues.

FA is a strong mutagen that induces damage to oxidative bases and breaks in the DNA strand and DNA-protein crosslinks [5, 82]. In this study, genetic damage was assessed using comet assay and MN test. Results showed an increase in the tail moment and MN frequency with the exposure to FA. Liu et al. [83] observed that the exposure to FA 1 at 10 mg/m3 for 20 weeks increased MN frequency in bone marrow of mice, but the difference was not significant. In an in vitro study with rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, comet assay showed that FA-induced DNA strand breakage increased in a dose-dependent way [84].

Epigenetic changes [DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA (miRNA) expression] can regulate gene expression without changes DNA sequence [85, 86]. DNA methylation is the most studied epigenetic modification in mammals [87, 88] and includes hypomethylation, which can lead to gene overexpression and hypermethylation, which can cause silencing of gene expression [88–90]. It is known that exposure to toxic agents is associated with DNA methylation changes, which may be increased, as demonstrated in the study by Qiu et al. [91] in rats exposed to vinyl chloride and in the study by Li et al. [88] with mice exposed to particulate matter 2.5. Regarding FA, epigenetic studies have shown that FA can lead to changes in the expression and activity of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which are enzymes that are responsible for maintaining methylation status in the genome and that catalyze the transfer of a methyl fraction of S-adenosyl-Lmetionin (SAM) for the cytosine of a CpG dinucleotide [92]. Liu et al. [92] showed that long-term exposure to FA reduced DNA methylation in 16HBE cells. On the other hand, Barbosa et al. [5] observed an increase in DNA methylation in individuals occupationally exposed to FA. However, studies on the influence of FA on global DNA methylation in mice are still scarce, and to our knowledge, our study is the first that evaluates this biomarker. Regarding the epigenetic results, we did not find a significant difference among the groups, but our study showed a trend toward an increase in global DNA methylation levels in the mice exposure to FA. In this line, more research is required to extend this study to better understand the mechanisms of epigenetic changes induced by the FA.

Studies have reported that the use of antioxidants prevented the lipid and protein damage resulting from FA. Gurel et al. [22] observed that the treatment with vitamin E showed an inhibitory effect of lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation on the frontal cortex and hippocampus of rats that received FA 10 mg/kg (i.p.) for 10 days. Zararsiz et al. [26] used omega 3 along with FA 10 mg/kg (i.p.) for 14 days and found a reduction in lipid oxidation in the renal tissue of Wistar rats. These findings are in agreement with the results of this study, which showed a reduction in lipid peroxidation levels and protein oxidation by applying melatonin.

Melatonin is especially effective as an antioxidant because it uses a wide variety of means to reduce oxidative stress [93], since it has several characteristics of an ideal antioxidant [94]. Due to its small molecular size and amphiphilic properties, its penetration into subcellular compartments is facilitated [30, 94, 95], which makes it present in adequate amounts in cells. Thus, melatonin eliminates several toxic reagents, including the hydroxyl radical (OH) and the peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−) (two main initiators of the peroxidation of fatty acids), and also takes advantage of its metabolites resulting from its reaction with ROS, in which also they are highly efficient radical scavengers [30, 93–95]. These effects are because the metabolism of melatonin, in addition to being carried out by enzymatic processes (CP450), is also performed through its interaction with ROS and reactive nitrogen species [96, 97]. In addition, melatonin has the ability to stimulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes including glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase, in addition to increasing glutathione synthesis [28].

In this context, it is possible to suggest that melatonin inhibited lipid peroxidation in the lung and liver as well as the formation of carbonyl proteins in the liver. This antioxidant effect of melatonin can be explained by its property of directing eliminating reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [28, 29] through a cascade reaction where the metabolites produced [2-OH-melatonin, 3-OH-melatonin-cyclic, 4-OH-melatonin, N1-acetyl-N 2-formyl-5-methoxyquinuramine (AFMK) and N1-acetyl-5-methoxyquinuramine (AMK)] neutralize reactive species [30, 93, 96]. Besides, due to its small molecular size and amphiphilic properties that facilitate its penetration in subcellular compartments, this substance can be incorporated into a superficial spot in the lipid layers of the membrane near the polar heads of these molecules, consequently protecting lipid molecules from being attacked by reactive species [30].

It is known that high levels of ROS are among the leading causes of DNA damage, in such a way that this oxidative damage to DNA can compromise genomic integrity. Thus, due to its antioxidant capacity, several mechanisms may be behind the protection of melatonin against damage to DNA, including the direct elimination of ROS and indirectly by stimulating antioxidant enzymes or modulating the repair pathways [98, 99]. Its amphiphilic property allows it to quickly cross morphophysiological barriers and provide local protection to DNA against locally generated ROS [93, 98, 100]. Pérez-González et al. (2018) found that melatonin metabolites can repair radical cations centered on guanine by transferring electrons to oxidized sites and radicals centered on C, the sugar portion of 2′-deoxyguanosine (2dG) by hydrogen atom transfer. In addition, the 6-hydroxymelatonin and 4-hydroxymelatonin metabolites must also repair OH adducts in the imidazole ring. Thus, these study’s results strongly suggest that the role of melatonin in preventing DNA damage can be mediated by its ability, combined with that of its metabolites, to directly repair oxidized sites in DNA through different chemical routes.

Regarding epigenetic changes, our results showed that pretreatment with melatonin tended to decrease overall DNA methylation, although without significant difference. A study by Ozen et al. [37] found that melatonin decreased FA-induced apoptosis in rat testicles. In addition to being an antioxidant, melatonin is probably an epigenetic regulator, as it and its metabolites can regulate DNMTs, as well as apoptosis, either by masking target sequences or by blocking the enzyme’s active site [101]. This fact is because melatonin reaches intracellular organelles, including the nucleus, where it accumulates and interacts with specific nuclear binding sites [30, 71, 94, 102]. Thus, it can be suggested that melatonin can protect against changes in DNA methylation induced by FA.

In contrast, pretreatment with melatonin did not significantly change NPSH levels or CAT activity in the tissues. However, in the lung, there was a slight but insignificant increase in NPSH. This lack of effect of melatonin in increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes may be the result of a reduced ROS rate due to the potent elimination of direct free radicals by the melatonin itself. Thus, we suggest that the main mechanism by which melatonin shows antioxidant activity, under the conditions of this study, was due to its cascade mechanism in which the interaction with free radicals leads to the formation of secondary and tertiary metabolites. These metabolites are capable of neutralizing toxic derivatives of oxygen and nitrogen, also playing an important role in maintaining the integrity of the genome.

Regarding the limitations of this study, it is highlighted that variable tissue responses may reflect differences in FA levels. Different findings among studies may happen due to the use of different species of rats or mice, the doses applied, time intervals, and test conditions. In addition, differently from this study, most of the works mentioned have evaluated FA effects in a short period of exposure and sometimes with higher doses than the ones necessary to induce detectable toxic effects. Another point to consider was the use of a full body inhalation chamber, which makes the airflow and the transport of inhaled FA throughout the respiratory tract different for each animal. Therefore, further studies on chronic and controlled exposure are needed to determine FA toxic effects, the protective effects of melatonin, and related parameters.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that the exposure to 5-ppm FA in mice resulted in oxidative damage to the lung and liver tissues. Also, an increase in NO levels, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and a thickening of the airway walls were observed. Besides, FA significantly induced DNA damage. Moreover, pretreatment with melatonin reduced oxidative damage and inflammatory in lung and liver tissues and prevented DNA damage in mice. Therefore, our results demonstrated that FA exposure with repeated doses might induce oxidative damage, inflammatory and genotoxic effects, and melatonin seems to minimize some of these toxic effects caused by FA inhalation in mice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil). This study was supported by the Federal University of Santa Maria and FIPE-UFSM.

Contributor Information

Letícia Bernardini, Graduate Program in Pharmacology, Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil.

Eduardo Barbosa, Graduate Program on Toxicology and Analytical Toxicology, University Feevale, Novo Hamburgo, RS 93525-075, Brazil.

Mariele Feiffer Charão, Graduate Program on Toxicology and Analytical Toxicology, University Feevale, Novo Hamburgo, RS 93525-075, Brazil.

Gabriela Goethel, Graduate Program in Pharmaceutical Sciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS 90610-000, Brazil.

Diana Muller, Department of Genetics, Instituto de Biociências, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS 90610-000, Brazil.

Claiton Bau, Department of Genetics, Instituto de Biociências, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS 90610-000, Brazil.

Nadine Arnold Steffens, Graduate Program in Pharmaceutical Sciences, Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil.

dos Carolina Santos Stein, Graduate Program in Pharmaceutical Sciences, Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil.

Rafael Noal Moresco, Graduate Program in Pharmaceutical Sciences, Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil.

Solange Cristina Garcia, Graduate Program in Pharmaceutical Sciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS 90610-000, Brazil.

de Marina Souza Vencato, Departament of Morphology, Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil.

Natália Brucker, Graduate Program in Pharmacology, Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Luch A, Frey FCC, Meier R et al. Low-dose formaldehyde delays DNA damage recognition and DNA excision repair in human cells. PLoS One 2014;9:e94149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zendehdel R, Fazli Z, Mazinani M. Neurotoxicity effect of formaldehyde on occupational exposure and influence of individual susceptibility to some metabolism parameters. Environ Monit Assess 2016;188:648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Q, Tian P, Zhai M et al. Formaldehyde regulates vascular tensions through nitric oxide-cGMP signaling pathway and ion channels. Chemosphere 2018;193:60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Costa S, Carvalho S, Costa C et al. Increased levels of chromosomal aberrations and DNA damage in a group of workers exposed to formaldehyde. Mutagenesis 2015;30:463–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barbosa E, Santos ALA, Peteffi GP et al. Increase of global DNA methylation patterns in beauty salon workers exposed to low levels of formaldehyde. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019;26:1304–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Katsnelson BA, Degtyareva TD, Privalova LI et al. Attenuation of subchronic formaldehyde inhalation toxicity with oral administration of glutamate, glycine and methionine. Toxicol Lett 2013;220:181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mohammadi S. Protective effect of N-acetyl cysteine against formaldehyde-induced neuronal damage in cerebellum of mice. Pharm Sci 2014;20:61–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8. ACGIH TLVs and BEIs based on the documentation of the threshold limit values for chemical substances and physical agents & biological exposure indices. 2010.

- 9. NIOSH Formaldehyde: method 2016. Man Anal methods 2003;2:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10. OSHA Formaldehyde Formaldehyde-Factsheet, 2011.

- 11. WHO WHO Guidelines for air quality: selected pollutants. WHO, Reginal Office for Europe, 2010, 1–484. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monakhova YB, Kuballa T, Mildau G et al. Formaldehyde in hair straightening products: rapid 1 H NMR determination and risk assessment. Int J Cosmet Sci 2013;35:201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bono R, Munnia A, Romanazzi V et al. Formaldehyde-induced toxicity in the nasal epithelia of workers of a plastic laminate plant. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2016;5:752–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Costa S, Costa C, Madureira J et al. Occupational exposure to formaldehyde and early biomarkers of cancer risk, immunotoxicity and susceptibility. Environ Res 2019;179:108740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salthammer T, Mentese S, Marutzky R. Formaldehyde in the indoor environment. Chem Rev 2010;110:2536–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu M, Tang H, Rong Q et al. The effects of formaldehyde on cytochrome P450 isoform activity in rats. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dorokhov YL, Sheshukova EV, Bialik TE et al. Human endogenous formaldehyde as an anticancer metabolite: its oxidation downregulation may be a means of improving therapy. Bioessays 2018;40:1800136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lan Q, Smith MT, Tang X et al. Chromosome-wide aneuploidy study of cultured circulating myeloid progenitor cells from workers occupationally exposed to formaldehyde. Carcinogenesis 2015;36:160–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. IARC Chemical agents and related occupations. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 2012;100:9–562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheng J, Zhang L, Tang Y et al. The toxicity of continuous long-term low-dose formaldehyde inhalation in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2016;38:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lino dos Santos Franco A, Gimenes-Júnior JA, Ligeiro-de-Oliveira AP et al. Formaldehyde inhalation reduces respiratory mechanics in a rat model with allergic lung inflammation by altering the nitric oxide/cyclooxygenase-derived products relationship. Food Chem Toxicol 2013;59:731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gurel A, Coskun O, Armutcu F et al. Vitamin E against oxidative damage caused by formaldehyde in frontal cortex and hippocampus: biochemical and histological studies. J Chem Neuroanat 2005;29:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang F, Li C, Liu W et al. Oxidative damage and genotoxic effect in mice caused by sub-chronic exposure to low-dose volatile organic compounds. Inhal Toxicol 2013;25:235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lino dos Santos Franco A, Correa-Costa M, Santos Durão ACC et al. Formaldehyde induces lung inflammation by an oxidant and antioxidant enzymes mediated mechanism in the lung tissue. Toxicol Lett 2011;207:278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gerin F, Erman H, Erboga M et al. The effects of ferulic acid against oxidative stress and inflammation in formaldehyde-induced hepatotoxicity. Inflammation 2016;39:1377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zararsiz I, Sonmez MF, Yilmaz HR et al. Effects of v-3 essential fatty acids against formaldehyde-induced nephropathy in rats. Toxicol Ind Health 2006;22:223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bejarano I, Espino J, Barriga C et al. Pro-oxidant effect of melatonin in tumour leucocytes: relation with its cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic effects. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2011;108:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Tan D-X et al. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J Pineal Res 2016;61:253–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jockers R, Delagrange P, Dubocovich ML et al. Update on melatonin receptors: IUPHAR review 20. Br J Pharmacol 2016;173:2702–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reiter RJ, Tan D-X, Galano A. Melatonin reduces lipid peroxidation and membrane viscosity. Front Physiol 2014;5:6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Asghari MH, Moloudizargari M, Baeeri M et al. On the mechanisms of melatonin in protection of aluminum phosphide cardiotoxicity. Arch Toxicol 2017;91:3109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dutta S, Saha S, Mahalanobish S et al. Melatonin attenuates arsenic induced nephropathy via the regulation of oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling cascades in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2018;118:303–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khaksar M, Oryan A, Sayyari M et al. Protective effects of melatonin on long-term administration of fluoxetine in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol 2017;69:564–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Özbek E, Turkoz Y, Sahna E et al. Melatonin administration prevents the nephrotoxicity induced by gentamicin. BJU Int 2000;85:742–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ozkanlar S, Kara A, Sengul E et al. Melatonin modulates the immune system response and inflammation in diabetic rats experimentally- induced by Alloxan. Endocr Res 2015;48:137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aydemir S, Akgun SG, Beceren A et al. Melatonin ameliorates oxidative DNA damage and protects against formaldehyde-induced oxidative stress in rats. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017;10:6250–61. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ozen OA, Kus MA, Kus I et al. Protective effects of melatonin against formaldehyde-induced oxidative damage and apoptosis in rat testes: an immunohistochemical and biochemical study. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2008;54:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zararsiz I, Kus I, Ogeturk M et al. Melatonin prevents formaldehyde-induced neurotoxicity in prefrontal cortex of rats: an immunohistochemical and biochemical study. Cell Biochem Funct 2007;25:413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zararsiz I, Sarsilmaz M, Tas U et al. Protective effect of melatonin against formaldehyde-induced kidney damage in rats. Toxicol Ind Health 2007;23:573–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olayaki LA, Alagbonsi IA, Abdulrahim AH et al. Melatonin prevents and ameliorates lead-induced gonadotoxicity through antioxidative and hormonal mechanisms. Toxicol Ind Health 2018;34:596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. OECD/OCDE OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals (OECD/OCDE 413). 2017.

- 42. Checkoway H, Dell LD, Boffetta P et al. Formaldehyde exposure and mortality risks from acute myeloid leukemia and other lymphohematopoietic malignancies in the US National Cancer Institute Cohort Study of Workers in Formaldehyde Industries. J Occup Environ Med 2015;57:785–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Costa S, Pina C, Coelho P et al. Occupational exposure to formaldehyde: genotoxic risk evaluation by comet assay and micronucleus test using human peripheral lymphocytes. J Toxicol Environ Heal Part A 2011;74:1040–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zendehdel R, Vahabi M, Sedghi R. Estimation of formaldehyde occupational exposure limit based on genetic damage in some Iranian exposed workers using benchmark dose method. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2018;25:31183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nielsen GD, Larsen ST, Wolkoff P. Recent trend in risk assessment of formaldehyde exposures from indoor air. Arch Toxicol 2013;87:73–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mueller JU, Bruckner T, Triebig G. Exposure study to examine chemosensory effects of formaldehyde on hyposensitive and hypersensitive males. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2013;86:107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976;72:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tatsch E, Bochi GV, da Silva Pereira R et al. A simple and inexpensive automated technique for measurement of serum nitrite/nitrate. Clin Biochem 2011;44:348–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Buege JA and Aust SD. Microsomal lipid peroxidation Methods in Enzymology, 1978;52:302–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Levine RL, Williams JA, Stadtman EP et al. Carbonyl assays for determination of oxidatively modified proteins Methods Enzymol, 1994;233:346–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys 1959;82:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem 1996;239:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aebi H. Catalase in vitro Methods Enzymology, 1984;105:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cestonaro LV, Marcolan AM, Rossato-Grando LG et al. Ozone generated by air purifier in low concentrations: friend or foe? Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017;24:22673–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lahiri DK, Numberger JI. A rapid non-enzymatic method for the preparation of HMW DNA from blood for RFLP studies. Nucleic Acids Res 1991;19:5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ramsahoye BH. Measurement of genome wide DNA methylation by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Methods 2002;27:156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rozhon W, Baubec T, Mayerhofer J et al. Rapid quantification of global DNA methylation by isocratic cation exchange high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem 2008;375:354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Goldner J. A modification of the masson trichrome technique for routine laboratory purposes. Am J Pathol 1938;14:237–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bruno E, Somma G, Russo C et al. Nasal cytology as a screening tool in formaldehyde-exposed workers. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2018;68:307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murta GL, Campos KKD, Bandeira ACB et al. Oxidative effects on lung inflammatory response in rats exposed to different concentrations of formaldehyde. Environ Pollut 2016;211:206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bakar E, Ulucam E, Cerkezkayabekir A. Protective effects of proanthocyanidin and vitamin E against toxic effects of formaldehyde in kidney tissue. 2015;90:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Li L, Hua L, He Y et al. Differential effects of formaldehyde exposure on airway inflammation and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Miranda SC, Peres Leal M, Brochetti RA et al. Low level laser therapy reduces the development of lung inflammation induced by formaldehyde exposure. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fujimaki H, Kurokawa Y, Kunugita N et al. Differential immunogenic and neurogenic inflammatory responses in an allergic mouse model exposed to low levels of formaldehyde. Toxicology 2004;197:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Maiellaro M, Correa-Costa M, Vitoretti LB et al. Exposure to low doses of formaldehyde during pregnancy suppresses the development of allergic lung inflammation in offspring. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2014;278:266–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lino dos Santos Franco A, Damazo AS, Beraldo de Souza HR et al. Pulmonary neutrophil recruitment and bronchial reactivity in formaldehyde-exposed rats are modulated by mast cells and differentially by neuropeptides and nitric oxide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2006;214:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lino dos Santos Franco A, Domingos HV, Damazo AS et al. Reduced allergic lung inflammation in rats following formaldehyde exposure: long-term effects on multiple effector systems. Toxicology 2009;256:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Wouters EFM et al. Nitric oxide and redox signaling in allergic airway inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005;7:129–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu D, Zheng Y, Li B et al. Adjuvant effects of gaseous formaldehyde on the hyper-responsiveness and inflammation in a mouse asthma model immunized by ovalbumin. J Immunotoxicol 2011;8:305–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Birben E, Murat U, Md S et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. WAO J 2012;5:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Erat M, Ciftci M. Effect of melatonin on enzyme activities of glutathione reductase from human erythrocytes in vitro and from rat erythrocytes in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;537:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kodavanti PRS, Royland JE, Moore-Smith DA et al. Acute and subchronic toxicity of inhaled toluene in male long-Evans rats: oxidative stress markers in brain. Neurotoxicology 2015;51:10–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Silva Macedo R, Peres Leal M, Braga TT et al. Photobiomodulation therapy decreases oxidative stress in the lung tissue after formaldehyde exposure: role of oxidant/antioxidant enzymes. Mediators Inflamm 2016;2016:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ye X, Ji Z, Wei C et al. Inhaled formaldehyde induces DNA-protein crosslinks and oxidative stress in bone marrow and other distant organs of exposed mice. Environ Mol Mutagen 2013;54:705–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yu G, Song X, Liu Y et al. Inhaled formaldehyde induces bone marrow toxicity via oxidative stress in exposed mice. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:5253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Huang Y, Wu C, Ye Y et al. The increase of ROS caused by the interference of DEHP with JNK / p38 / p53 pathway as the reason for hepatotoxicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rossner P, Svecova V, Milcova A et al. Seasonal variability of oxidative stress markers in city bus drivers. Mutat Res Mol Mech Mutagen 2008;642:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lima LF, Murta GL, Bandeira ACB et al. Short-term exposure to formaldehyde promotes oxidative damage and inflammation in the trachea and diaphragm muscle of adult rats. Ann Anat 2015;202:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ramos C d O, Nardeli CR, Campos KKD et al. The exposure to formaldehyde causes renal dysfunction, inflammation and redox imbalance in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol 2017;69:367–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Brandão R, Santos FW, Oliveira R et al. Involvement of non-enzymatic antioxidant defenses in the protective effect of diphenyl diselenide on testicular damage induced by cadmium in mice. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2009;23:324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pontel LB, Rosado IV, Burgos-Barragan G et al. Endogenous formaldehyde is a hematopoietic stem cell genotoxin and metabolic carcinogen. Mol Cell 2015;60:177–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jiang S, Yu L, Cheng J et al. Genomic damages in peripheral blood lymphocytes and association with polymorphisms of three glutathione S-transferases in workers exposed to formaldehyde. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2010;695:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Liu Y, Yu D, Xiao S. Effects of chronic exposure to formaldehyde on micronucleus rate of bone marrow cells in male mice. J Pak Med Assoc 2017;67:933–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. She Y, Li Y, Liu Y et al. Formaldehyde induces toxic effects and regulates the expression of damage response genes in BM-MSCs. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2013;45:1011–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Baccarelli A, Bollati V. Epigenetics and environmental chemicals. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21:243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chen D, Fang L, Mei S et al. Regulation of chromatin assembly and cell transformation by formaldehyde exposure in human cells. Environ Health Perspect 2017;125:97019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Barros SP, Offenbacher S. Epigenetics: connecting environment and genotype to phenotype and disease. J Dent Res 2009;88:400–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Li Z, Li N, Guo C et al. Genomic DNA methylation signatures in different tissues after ambient air particulate matter exposure. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019;179:175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. De Conti A, Tryndyak V, Vontungeln LS et al. Genotoxic and epigenotoxic alterations in the lung and liver of mice induced by acrylamide: a 28 day drinking water study. Chem Res Toxicol 2019;32:869–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Koturbash I, Scherhag A, Sorrentino J et al. Epigenetic alterations in liver of C57BL/6J mice after short-term inhalational exposure to 1,3-butadiene. Environ Health Perspect 2011;119:635–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Qiu Y, Xu Z, Wang Q et al. Association between methylation of DNA damage response-related genes and DNA damage in hepatocytes of rats following subchronic exposure to vinyl chloride. Chemosphere 2019;227:323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Liu Q, Yang L, Gong C et al. Effects of long-term low-dose formaldehyde exposure on global genomic hypomethylation in 16HBE cells. Toxicol Lett 2011;205:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. García JJ, López-Pingarrón L, Almeida-Souza P et al. Protective effects of melatonin in reducing oxidative stress and in preserving the fluidity of biological membranes: a review. J Pineal Res 2014;56:225–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Galano A, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin as a natural ally against oxidative stress: a physicochemical examination. J Pineal Res 2011;51:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Fischer TW, Kleszczyński K, Hardkop LH et al. Melatonin enhances antioxidative enzyme gene expression (CAT, GPx, SOD), prevents their UVR-induced depletion, and protects against the formation of DNA damage (8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine) in ex vivo human skin. J Pineal Res 2013;54:303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Tan DX, Manchester LC, Esteban-Zubero E et al. Melatonin as a potent and inducible endogenous antioxidant: synthesis and metabolism. Molecules 2015;20:18886–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Allegra M, Reiter RJ, Tan D-X et al. The chemistry of melatonin’s interaction with reactive species. J Pineal Res 2003;34:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Galano A, Tan D-X, Reiter R. Melatonin: a versatile protector against oxidative DNA damage. Molecules 2018;23:530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Pandey N, Giri S. Melatonin attenuates radiofrequency radiation (900 MHz)-induced oxidative stress, DNA damage and cell cycle arrest in germ cells of male Swiss albino mice. Toxicol Ind Health 2018;34:315–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sliwinski T, Rozej W, Morawiec-Bajda A et al. Protective action of melatonin against oxidative DNA damage—chemical inactivation versus base-excision repair. Mutat Res Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2007;634:220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fang Y, Deng S, Zhang J et al. Melatonin-mediated development of ovine cumulus cells, perhaps by regulation of DNA methylation. Molecules 2018;23:494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Collin F. Melatonin: action as antioxidant and potential applications in human disease and aging. Toxicology 2010;278:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]