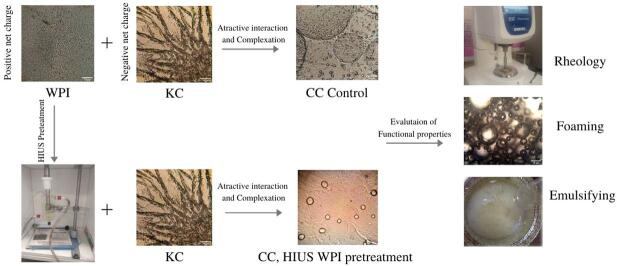

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Complex coacervation, High-intensity ultrasound, Whey protein isolate, Kappa carrageenan, Functional properties

Highlights

-

•

Complex coacervation between WPI-KC using a US pretreatment was achieved.

-

•

Despite WPI structure change by US treatment, coacervation with carrageenan remains.

-

•

Functional properties improvement was observed in US pretreated complex coacervates.

Abstract

The aim of this work was to evaluate the influence of high-intensity ultrasound (HIUS) treatment on whey protein isolate (WPI) molecular structure as a previous step for complex coacervation (CC) with kappa-carrageenan (KC) and its influence on CC functional properties. Protein suspension of WPI (1% w/w) was treated with an ultrasound probe (24 kHz, 2 and 4 min, at 50 and 100% amplitude), non HIUS pretreated WPI was used as a control. Coacervation was achieved by mixing WPI and KC dispersions (10 min). Time and amplitude of the sonication treatment had a direct effect on the molecular structure of the protein, FTIR-ATR analysis detected changes on pretreated WPI secondary structure (1600–1700 cm−1) after sonication. CC electrostatic interactions were detected between WPI positive regions, KC sulfate group (1200–1260 cm−1), and the anhydrous oxygen of the 3,6 anhydro-D-galactose (940–1066 cm−1) with a partial negative charge. After ultrasound treatment, a progressive decrease in WPI particle size (nm) was detected. Rheology results showed pseudoplastic behavior for both, KC and CC, with a significant change on the viscosity level. Further, volume increment, stability, and expansion percentages of CC foams were improved using WPI sonicated. Besides, HIUS treatment had a positive effect on the emulsifying properties of the CC, increasing the time emulsion stability percentage. HIUS proved to be an efficient tool to improve functional properties in WPI-KC CC.

1. Introduction

Complex coacervation occurs when two compounds with opposite net charges interact on a liquid media, producing a spontaneous separation phase as a result of the complexation, producing two phases, one rich in solvent and the other rich in colloidal aggregates or coacervates [1], [2]. This process depends on many environmental and controllable factors like pH, ionic strength, biopolymers nature, mixing weight ratio, conformational molecular changes, molecular weight, density charge and biopolymer flexibility [3]. Nowadays, complex coacervation systems (CC) from proteins and polysaccharides, has been more studied in order to obtain handmade complexes, through controlling environmental factors. Recently, they have been used in food processing because both biopolymers have specific functional properties that may increase when they interact. Meanwhile, Whey protein isolate (WPI) presents important functional properties such as gelling, foaming, thickening, water binding and emulsifying [4]. Meanwhile, kappa Carrageenan (KC) could be used for increasing the viscosity in aqueous systems and also as a gelling agent by its rheological properties. Several studies have reported the increase in functional properties by CC use such as emulsifying, foaming, water holding capacity, among others [3], [5], [6], [7].

Kappa Carrageenan (KC) is a sulfated polysaccharide extracted from edible red algae, it is composed by D-galactose 4-sulfate and 3, 6-anhydro-galactopyranose units bounded by α-1,3 and β-1,4 glyosidic bond [8], [9], [10]. Since KC is a sulfated polysaccharide, it has a negative net charge in a wide pH range, which allows it to interact with positively charged compounds like WPI under its isoelectric point where the protein has a positive net charge [11], [12], [13].

Whey protein isolate (WPI) is obtained by ultrafiltration process from milk whey, which is a byproduct in cheese making process and has become popular as a food additive because of their nutritional, functional and active properties [4], [14], [15]. It is mainly composed by proteins such as β-lactoglobulin (β-LG) and α-lactalbumin (α-LA) along with small amounts of glycomacropeptide (GMP), immunoglobulins (Igs), bovine serum albumin (BSA), lactoferrin (LF), lactoperoxidase (LP), proteose peptone (PP), among others. β-LG, the main protein in whey (~60%) conformed by a “calyx” or globulet-like structure, with the capacity to bind with numerous hydrophobic and amphiphilic ligands [16]. To improve the accessibility to reactive groups, it is necessary to previously denature and/or unfold globular compact structures formed mainly by albumins and globulins fractions (ionic, hydrophobic, -SH groups) and to promote the interaction with other polymers, such as complex coacervation [17].

High-Intensity Ultrasound (HIUS) is a non-thermal, green technology that has been used to induce conformational changes in proteins affecting physicochemical properties of a number of protein sources including whey protein isolate/concentrate, where the main changes occur in surface hydrophobicity, viscosity, particle size, and formation of protein–protein aggregates [18], [19], [20], [21], [22].

Ultrasound is an acoustic wave, imperceptible for the human audition with a frequency higher than 20 kHz. This technology particularly employs frequencies ranging from 100 kHz to 1 MHz, its fundamental work process is attributed to the ultrasonic cavitation, which refers to the rapid formation and collapse of gas bubbles in a liquid media, generating pressure and temperature increases at specific points by very short periods of time (milliseconds), producing changes on the surrounding molecules in the specific places where the bubbles collapse due to pressure differentials [23]. Due to cavitation effects, ultrasonic treatment can increase the probability of contact between the protein-polysaccharide complex and bioactive compounds, and increase the stability of complex coacervation [24].

Many studies have reported the study of CC from proteins and polysaccharides but only a few studies have investigated the influence of ultrasonication as a previous step for induced protein conformational changes. HIUS has proven useful on the improvement of CC functional properties like emulsion stabilization on whey protein concentrate-pectin complexes [25], and also to encapsulate polyphenolic compounds such as resveratrol [24]. One of the main limitations between protein/polysaccharide interactions is their molecular structure and its ability to interact. In this sense, the use of HIUS may modify the structure of biopolymers and consequently, their technological properties [17]. Based on the many studies, it is hypothesized that ultrasound treatment could induce modifications of the physical and functional properties of WPI-KC complex coacervation, which could be useful in the development of CC systems with improved functional properties. For this, the aim of this research was to evaluate the effect of HIUS on the structural, physicochemical and functional properties of WPI-KC CC, using the ultrasound treatment as a previous step on the WPI conformational modification.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Refined KC (PEISA HX Gel RP 1000, México) and WPI (BiPro, USA) were employed. The chemical composition of the WPI (w/w) was protein: 91.0%, calcium: 0.05%, Sodium: 0.85%. Other chemicals used in this study were analytical and reagent grade purchased through Sigma- Aldrich (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Preparation of stock dispersions

WPI (1% w/w) and KC (1% w/w) stock dispersions were prepared by dispersing in deionized water with regular stirring for 24 h at 25 °C to guarantee complete hydration of biopolymers in order to use on the following day. Sodium benzoate (0.1% w/w) was added to prevent microbial growth.

2.3. Ultrasonic treatment of WPI dispersion

For ultrasound treatments, a HIUS probe equipment (Hielscher UP400S, Germany, power 400 W, frequency 24 kHz) was used. Aliquots of 100 mL of WPI stock dispersion were placed in a 150 mL flat-bottomed conical reactor, then a 22 mm diameter titanium probe was submerged 3 cm in the liquid sample during ultrasonication. The ultrasound irradiation was produced directly from the tip under continuous mode. Each aliquot was treated separately. The following HIUS treatments for WPI were applied: Amplitude: 50 and 100% for 2 and 4 min. During ultrasound treatments, the temperature was controlled by a recycling cool bath at 25 ± 2 °C. The actual power delivered to the dispersed sample was determined by the calorimetric method, based on the equations presented by Kentish [26].

2.4. Protein surface hydrophobicity measurements

Surface hydrophobicity (S0) of the WPI was determined by fluorometric test. As Chandrapala et al. [27] suggested, a stock solution of 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulphonate (ANS) 8 mM and stock solutions of protein in phosphate buffer 0.1 M, pH 7 were prepared using concentration ranges from 0.005 to 0.025% w/w. 20 µL of the ANS solution was added to 4 mL of each diluted protein solution, vortexed and kept in the dark, then from lowest to highest concentration of protein, the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) of each solution was measured using a fluorimeter (Ocean Optics USB4000, USA) at an excitation and emission wavelength of 390/470 nm, respectively. Net RFI was determined by subtracting the intensity of the control (buffer pH 7.0), from the intensity of the protein solution with ANS, at each protein concentration. The degree of surface hydrophobicity (S0) was expressed as the initial slope: fluorescence intensity/ protein concentration (%), and was calculated from the fluorescence intensity vs. protein concentration plot, using the linear least squares regression analysis through Microsoft Excel 2016 software.

2.5. Particle size (PS) distribution and zeta potential determination

The PS distribution and Zeta potential (ζ, mV) of WPI samples were determined after ultrasound treatments, through a Microtrac DSL device (Nanotrac Wave II, USA), 1 mL of the dispersed sample was used. All measurements were carried out by triplicate at 25 °C.

2.6. WPI-KC complex coacervation

2.6.1. Turbidimetric analysis at different pHs

Different mixtures of WPI and KC were prepared by mixing the stock solutions at 1:1 (w/w) WPI: KC mixing ratio and a total biopolymer concentration of 2% (w/w). The mixtures were acidified gradually by the addition of 0.1 M HCl (pH range of 3–7). The optical density (OD) of stock solutions of WPI, KC and WPI-KC mixtures were assessed over time during the slow acidification using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Sci Spectroscopy 14-386-441, USA) at 600 nm, using plastic cuvettes (1 cm path length). Deionized water was used as a blank reference. The optimum pH for coacervation corresponds to the pH value at which the highest optical density was observed, this value as well as the critical pH intervals in which there are coacervation stage transitions (pH opt: maximum optical density, pHⱷ1: formation of insoluble complexes, and pHⱷ2: dissolution of complexes) were determined graphically from the curve [11], [12]. All measurements were carried out by triplicate.

2.6.2. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR)

WPI, KC and WPI-KC samples were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectrometry (FTIR), 3 µL of each sample were used. For this determination, FTIR spectrometer, (Bruker Vertex 70, USA) ATR mode (with a Platinum ATR accessory), in the infrared region between 4000 and 400 cm−1 was used. All the data were analyzed using Origin 8.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). The modification on the secondary structure of WPI by HIUS treatment was determined from amide I region (1600–1700 cm−1) second derivative deconvolution and peak fitting (R2 > 0.98), employing the assignment of amide I band positions to secondary structure [28].

2.6.3. Optical microscopy

To describe the WPI-KC complex coacervation and foams structure an optical microscopy technique was employed at 40x and 10x, respectively. Optical microscopy images were obtained using an optical microscope (Carl Zeiss 467230, Germany). Microscope analysis was carried out using the IMAGEJ (Java Image Processing Program software, USA).

2.7. Functional properties of complex coacervates

2.7.1. Rheological behavior

KC, WPI, and CC rheological properties were determined using a Brookfield rheometer (RST-CPS, USA) with temperature control, coupled to the RCT-50 measuring steel cone at 25 °C, and rotation speed: 2000 1/s. The data on the rheological behavior were adjusted to the Power Law (Eq. 1) and Herschel–Bulkley (Eq. 2) model using the following equations:

| T = K * γn | (1) |

| T = T0 + (K * γn) | (2) |

where γ is the shear speed, K and n are constants, the viscous index and the consistency index respectively, T represents the shear stress, and T0 is the shear stress at time 0.

2.7.2. Foaming capacity

Volume increase, foaming stability and expansion were calculated according to the equations used by Silva Diniz et al. [29]. To evaluate the foaming capacity, 70 mL of the WPI dispersions and 70 mL of the complex coacervates dispersions were used. Each sample was homogenized in a 150 mL beaker with a homogenizer (Dremel 220, USA) for 60 s at 11,000 rpm. The total volume and foam volume were measured immediately after homogenization. The percentage of volume increase or overrun was calculated employing Eq. 3:

| VI (%) = [(PV2-PV1)/ PV1] *100 | (3) |

where VI (%), represents the volume increase, PV2 is the protein suspension volume after agitation, PV1 protein suspension volume before agitation. The variation in foam volume at 25 °C was measured immediately after stirring, at intervals of 5 min for 1 h.

The percentage of foaming stability (FS%) and foam expansion capacity (FE%), were evaluated using Eq. 4 and 5:

| FS(%) = (Vff/Vf0)*100 | (4) |

| FE(%) = (Vf0/Vd)*100 | (5) |

where FS (%) is the foam stability percentage, Vf0, is the foam volume at time zero and Vff is the foam volume after time t, FE (%) is the percentage of foam expansion and Vd is the initial volume of the dispersion.

2.7.3. Solubility determination

CC were lyophilized in freeze dryer (Labconco 7740021, USA). Lyophilized CC powders were dispersed (1% w/v) in deionized water at 25 °C and stirred at 110 rpm for 30 min. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. Aliquots of each supernatant were taken with volumetric pipettes and transferred to previously weighed aluminum dishes, for dried to constant weight in an incubator at 100 °C. The solubility was calculated from the difference in weight [30].

2.7.4. Emulsifying properties

Oil-in-water emulsions were prepared at room temperature by adding 12 mL sunflower oil into 48 mL of 3% CC dispersions (w/v). The mixtures were homogenized in 150 mL beaker with a homogenizer (Dremel 220, USA) for 90 s at 11,000 rpm to form emulsions [31], [32]. The emulsifying activity index (EAI) and emulsion stability index (ESI) were determined by the turbid metric technique as previously described [32], [33]. Immediately after emulsion formation, a 10 µL aliquot was transferred into 5.0 mL of pH-adjusted water containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), vortexed for 10 s. The absorbance was measured at 500 nm using an UV– Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Sci Spectroscopy 14-386-441, USA). A second 10 µL aliquot of the emulsion was taken 10 min later, following the same procedure. EAI and ESI values were determined by using the equations (7) and (8) [32], [33].

| EAI (m2/g) = (2*2.303*A0*N) / (c*ϕ*10000) | (7) |

| ESI (min) = (A0/ ΔA)*t | (8) |

where A0 is the absorbance at 500 nm of the diluted solution immediately after emulsion formation, N is the dilution factor (500 x), c is the weight of protein per volume before the emulsion was formed (g/mL), ⱷ is the oil volume fraction of the emulsion, ΔA is the change in absorbance between 0 and 10 min (A0-A10) and t is the time interval of 10 min.

2.7.5. Gelation properties

To induce thermal gelation, CC dispersions were thermally treated in a water bath at 95 °C for 10 min, then gelation was carried out at room temperature [34].

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out at least by duplicate. The results were reported as averages with standard deviations and were submitted to variance analysis (ANOVA) and Tukey test was applied to evaluate significant differences among the mean values (p < 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of sonication on the physicochemical properties of WPI

The different HIUS treatments on WPI and the actual power delivered to the samples were: a) 50% amplitude, 2 min, calorimetric power = 33.48 ± 2.0 W; b) 50% amplitude, 4 min, calorimetric power = 38.12 ± 3.0 W; c) 100% amplitude, 2 min, calorimetric power 83.18 ± 6.0 W and d) 100% amplitude, 4 min, calorimetric power = 67.05 ± 3.62 W. The energy consumption for the treatments 50% and 100% amplitude was 0.2 kWh/L and 0.4 kWh/L, respectively.

The effectiveness of the sonication treatments, was evaluated by the changes on WPI surface hydrophobicity, particle size, Zeta potential and FTIR-ATR amide I (1600–1700 cm−1) second derivative deconvolution.

3.1.1. Surface hydrophobicity measurements

It is well known the importance of protein structure and hydrophobic interactions for the stability, conformation and functional properties of proteins (emulsifying and foaming capacity). Due to the macromolecular structure of proteins, the surface hydrophobicity has more influence on functionality than the total hydrophobicity [27]. In general terms, protein regions associated with high hydrophobicity are directed towards the interior of the protein and not exposed to the surface, with the ultrasonic treatment, the hydrophobic groups of the proteins initially localized in the interior of the molecule are exposed to the more polar surrounding environment [35], [36]. The surface hydrophobicity of WPI dispersions as a function of sonication treatment are present in Table 1. WPI surface hydrophobicity decreased after 50% amplitude treatments, which is a sing of protein aggregation, the partially denaturized proteins might cause more extensive bonding, which in turn protects the hydrophobic regions of the proteins [27], as the amplitude of the sonication treatment increased (100% amplitude), the surface hydrophobicity increases, high-intensity ultrasound treatment (HIUS) induced structural changes in proteins that were associated with partial scission of intermolecular hydrophobic interactions due to the mechanical effects of cavitation [22]. Ultrasound can modify the conformation of the whey protein through affecting hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, by acoustic and hydrodynamic cavitation [37], increasing surface hydrophobicity, as had been demonstrated in several studies [36], [37]. These results also support the trends observed in secondary structure data (Table 3), where conformational changes in the protein structure induced by ultrasound treatment were observed.

Table 1.

WPI Surface hydrophobicity measurements.

| HIUS treatment on WPI | Surface Hydrophobicity Index (S0) |

|---|---|

| – | 471.78 ± 1.97b |

| 50%A, 2 min | 437.5 ± 12.87b,c |

| 50%A, 4 min | 385.6 ± 28.0c |

| 100%A, 2 min | 548.5 ± 14.6a |

| 100% A, 4 min | 502.1 ± 14.9a,b |

Different letters in the same column present significant difference (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Secondary WPI structure estimated from deconvolution of amide I spectra, relative peak area (%).

| Secondary structure relative peak area (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIUS treatment on WPI | R2 | α- helix | β-sheets | β- turns | Disordered |

| – | 0.990 | 18.7 ± 0.31a | 33.55 ± 0.07c | 31.47 ± 0.63c | 16.28 ± 0.26b |

| 50%A, 2 min | 0.992 | 11.88 ± 0.09b | 36.35 ± 0.29b,c | 34.88 ± 0.14b | 16.89 ± 0.34b |

| 50%A, 4 min | 0.986 | 5.43 ± 0.13d | 39.92 ± 2.72b | 42.85 ± 2.56a | 11.8 ± 0.29c |

| 100%A, 2 min | 0.974 | 9.63 ± 0.12c | 46.29 ± 0.23a | 24.4 ± 0.06c | 19.68 ± 0.41a |

| 100% A, 4 min | 0.971 | 8.83 ± 0.46c | 48.78 ± 0.19a | 23.28 ± 0.4c | 19.1 ± 0.67a |

For the same sample, groups with different capital letters have a significant statistical difference (p < 0.05).

3.1.2. Particle size distribution

Particle size distribution (Table 2) showed that ultrasonic treatments applied have a significant influence on particle size reduction (p < 0.05) compared to the WPI untreated. In general, as the treatment amplitude increases (from 50 to 100%) the particle size decreases, which had been reported in other studies [22], [35]. Ultrasound treatment has been reported to have significant effects on the particle size reduction of various proteins suspensions, including whey proteins; the main mechanisms involved are ultrasonic cavitation, microstreaming and turbulent forces that can reduce particle size of large macromolecules and disrupt protein aggregates, increasing particle surface area and improving particle interactions [36], [38]. The particle size decreasing after ultrasonic treatment also generate significant structural changes disrupting electrostatic interactions such as, hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, partial cleavage of intermolecular hydrophobic interactions, rather than peptide or disulphide bonds [22], leading improvements of emulsifying and foaming properties without modifications in the primary structure and the molecular weight, because the energy is insufficient to hydrolyze the peptide bond [37].

Table 2.

WPI particle size and zeta-potential after HIUS treatment.

| HIUS treatment on WPI | Particle size, Mz (nm) | Zeta Potential |

|---|---|---|

| – | 287.75 ± 3.75a | 14.90 ± 0.56a |

| 50%A, 2 min | 254.05 ± 5.30b | 15.65 ± 0.64a |

| 50%A, 4 min | 223.95 ± 0.636c | 15.70 ± 0.42a |

| 100%A, 2 min | 217.25 ± 2.47c | 15.30 ± 0.00a |

| 100% A, 4 min | 190.60 ± 10.75d | 15.60 ± 0.28a |

Different letters in the same column present significant difference (p < 0.05).

3.1.3. Zeta potential

Through zeta-potential it is possible to known the stability of colloidal systems by measuring the electrophoretic properties of the colloidal particles. As an important parameter, surface charge of particles can affect their solubility and interactions with other particles [32], [39]. The effects of ultrasound treatment on zeta-potential are shown in Table 2. As expected [11], the untreated whey protein particles presented positive zeta-potential value (cationic character) 14.9 ± 0.56 mV at pH lower (pH = 3) than its isoelectric point (IEP: 5–5.2) [13], [40], [41]. At this pH, WPI dispersion exhibited the maximum cationic character in a zeta-potential value [11]. After sonication treatments, although there was an increase in zeta potential, this increase was not statistically modified (p < 0.05), maintaining the cationic character of WPI protein, which is important characteristic for complex coacervation.

3.1.4. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR), deconvolution of WPI amide I second derivative

Several studies have analyzed the protein structural changes after ultrasound treatment [23], [32], [37]. Conformational changes on WPI are the result of partial splitting, inhibition of aggregate formation or protein–protein interactions [42]. Proteins stability depends on their ability to form the maximum number of hydrogen bonds, complemented by Van der Waals interactions, derived from the hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen and the amine hydrogen of the peptide bonds, however, changes in the availability of –OH groups due to HIUS treatment can disrupt the balance causing structural changes [14]. For the formation of secondary structure elements, a specific type of electrostatic interactions, the hydrogen bonds, are often claimed as the main stabilizing force; an hydrogen atom that is covalently bound to a nitrogen, gets in proximity of, and is therefore attracted by, an electronegative oxygen [43]. The stable secondary structure elements then further develop interactions between themselves and form a tertiary structure which is the folding of secondary structure into distant arrangements know as domains [44]. In this sense, secondary structure of the proteins can be used to predict the tertiary structure [45]. In this work, FTIR-ATR was employed to characterize molecular protein secondary structure as a function of HIUS treatment conditions, which is commonly based on the amide I band (C = O, N = O vibrations) analysis (1700–1600 cm−1). For this purpose, second derivative of this region was obtained and then de-convoluted and peak fitted (R2 > 0.97). The bands analyzed were those that correspond to the contributions of β-sheets (1617–1642 cm−1), β-turns (1672–1691 cm−1), α-helix (1655–1662 cm−1) and random structures (1646–1652 cm−1) [46]. The configuration of the secondary structures has a great influence on the stability of the protein structure [43], in order to quantify the variation of the corresponding contributions, areas under the curves were calculated and presented in Table 3. Infrared studies have suggested that the β-Lg (~60% of WPI) secondary structure consists of 10 to 15% of α-helices, ~50% of β-sheets and ~20% of turns, the remainder ~15% represents amino acid residues in a disorganized non-repetitive arrangement without a well-defined structure [47]. The modification on secondary structure from HIUS treatments (Table 3), include significant (p < 0.05) conformational changes in all the treatments; however, treatments applied at 100% amplitude are those that in general terms included a decrease on α-helix (1655–1662 cm−1), an increase on β sheets (1617–1642 cm−1), turns (1672–1691 cm−1) and disordered structures (1646–1662 cm−1). The reduction in α-helix content might correspond to the partial unfolding of the α-helical region that is caused by ultrasonic cavitation, because ultrasound treatment can reduce the number of intramolecular bonds, by the other hand, the increase in random coils can be attributed to the transformation of β-turns into random coils [38]. Additionally, when a protein presented an increase in disordered structures, it is believed that it has undergone a greater conformational changes [46]. The increase in β-sheet structure contributed to the exposure of the hydrophobic regions of the protein [38]. Wang et al. [42] suggest that there is a positive correlation between β-sheet-random coil content and surface hydrophobicity, the higher β-sheet and random coil content, the bigger value of surface hydrophobicity, which is in concordance with the results obtained in the present work (Table 1, Table 3), being the most significant results those corresponding to 100% amplitude, 2 min treatment. The most probable reason for this behavior is that the content of α-helix in protein is low and the protein molecular structure is relatively lost when the β-sheet and random coil content is high. Besides, the hydrophobic sites in the protein are more largely exposed, increasing the surface hydrophobicity by unmasking internal hydrophobic regions as a consequence of the unfolding of the proteins, this influence the protein functional properties [36], [42].

3.2. Complex coacervation

3.2.1. Turbidimetric analysis at different pHs

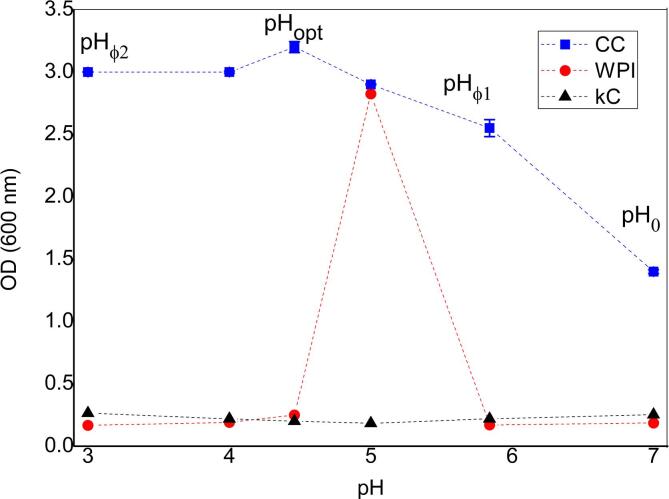

Protein ionization due to amine and carboxyl groups is determined by pH, its charge largely determines electrostatic interactions with other biopolymers, including polysaccharides. It is recognize that, the major driving force involved in complex coacervation between protein and anionic polysaccharides, such as KC, in solution is the electrostatic interaction [2], [48], thus pH is a key factor for complex coacervation. To identify the optimal pH, the optical density (OD) curves were obtained as a function of changes in pH maintaining the biopolymers ratio (Fig. 1), KC and WPI were used as a control.

Fig. 1.

Optical density as a function of pH for: WPI, KC, WPI-KC CC.

KC is a sulfated polygalactan negatively charged in a wide pH range due to the presence of sulfate groups in its molecular structure [8], [9], [10], regardless of the pH level, no significant changes in the OD of the KC titration curve were observed. However, in the case of WPI, a significant increase in the turbidity level (pH ~ 5) was detected, this increase corresponds to the average isoelectric point (IEP) of the WPI, which is in agreement with previous reports (WPI, IEP = 5.2) [41], [49]. WPI solutions tend to be stable over a wide pH range except close to its IEP, where the dimer- monomer equilibrium of β-Lg is shifted toward the monomer, changing the structure of the aggregates considerably [50], as a consequence, maximum turbidity level is achieved. The pH lower or higher that the IEP resulted in a steady decrease in the turbidity [41], pH levels below the IEP confer a protein positive net charge, while pH levels above the isoelectric point confer a negative net charge [11], [40].

By the other hand, as complex coacervation depends on electrostatic interactions and therefore on pH, there were different stages when the process was carried out. Fig. 1 shows the characteristic transition stages observed by changes in turbidity of the WPI-KC complex. In the first stage, called pH0, the presence of co-soluble biopolymers was exhibited, where non-electrostatic interactions occurred between them (pH0 ~ 7). At this stage, the optical density level was the minimum, the interaction between the biopolymers does not occur because both materials presented a negative charge and repelled each other electrostatically. The second stage, pHφ1, occurred when the pH was reduced, at this point (pHφ1 ~ 6) the interaction between both biopolymers begins to increase, as the OD increase, and the insoluble complexes are formed. Subsequently, as the pH decreases, the complexes continued to grow in size until the system reached the third stage, the optimum formation point, called pHopt, which was evidenced by a maximum in OD (pHopt ~ 4.5), where maximum complex formation was achieved. Subsequently, a decrease in OD was observed (pHϕ2 ~ 4) indicating the dissociation caused by protonation of reactive groups, resulting in less interactions and the dissociation of the complex structure [11], [51]. Complex coacervation, protein–polysaccharide, could occur when the pH of the mixture was lower than the IEP of the protein. At this pH, the protein possessed a net positive charge whereas the polysaccharide still possessed a negative charge [2]. From this experiment, it was possible to determine that the optimum pH for coacervation was reached when CC system pH ~ 4.5. This pH media level was achieved by mixing WPI-KC, when WPI (pH 3) had a positive net charge and KC (pH 7) presented a negative net charge, allowing that both biopolymers interacted electrostatically.

On the other hand, OD of sonicated WPI and HIUS WPI- KC complex coacervates was determined in order to know the influence of the ultrasonic treatment. KC and WPI, CC without treatment were used as a control, these results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

WPI, KC and CC Optical density (600 nm).

| HIUS treatment | OD (600 nm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WPI | CC | KC | |

| – | 0.120 ± 0.013b | 2.859 ± 0.027a | 0.229 ± 0.116 |

| 50%A, 2 min | 0.283 ± 0.015a | 2.989 ± 0.147a | |

| 50%A, 4 min | 0.262 ± 0.021a | 2.838 ± 0.123a | |

| 100%A, 2 min | 0.117 ± 0.007b | 2.561 ± 0.325a | |

| 100% A, 4 min | 0.051 ± 0.008c | 2.542 ± 0.344a | |

Different letters in the same column present significant difference (p < 0.05). WPI, KC, and CC without HIUS treatment were used as a control.

It is well known that ultrasonic treatment could modify the protein molecular structure, this change can be evaluated by changes in solution turbidity. In this sense, a significant increase in OD level (p < 0.05) was detected in 50% amplitude (33–38 W) treatments. Martini, Potter, and Walsh [52] suggest that ultrasonic low energy treatments could increase turbidity level, although the mechanism that leads an increase in the OD of protein samples is not entirely clear. A possible mechanism may involve changes on the tertiary structure of whey proteins and/or the minimization of protein–protein interactions that leads to aggregation and as a consequence an increase in turbidity. Contrarily, as the ultrasonic treatment increases, 100% amplitude (67–83 W) there was a significant decrease in the level of OD. This decrease could be based on the scission of the main chain, due to ultrasonic cavitation, also resulting in a decrease on the particle size of the WPI [39], which is in concordance with the results of particle size (Table 2).

CC samples did not present significant differences (p < 0.05) with respect to the control, so it is inferred that protein ultrasonic pre-treatment does not have influence on the OD level of the coacervates systems.

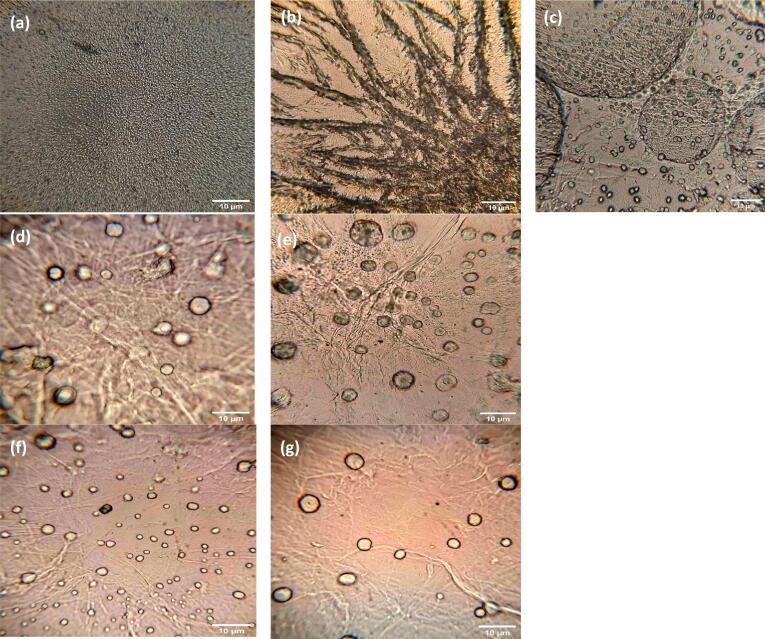

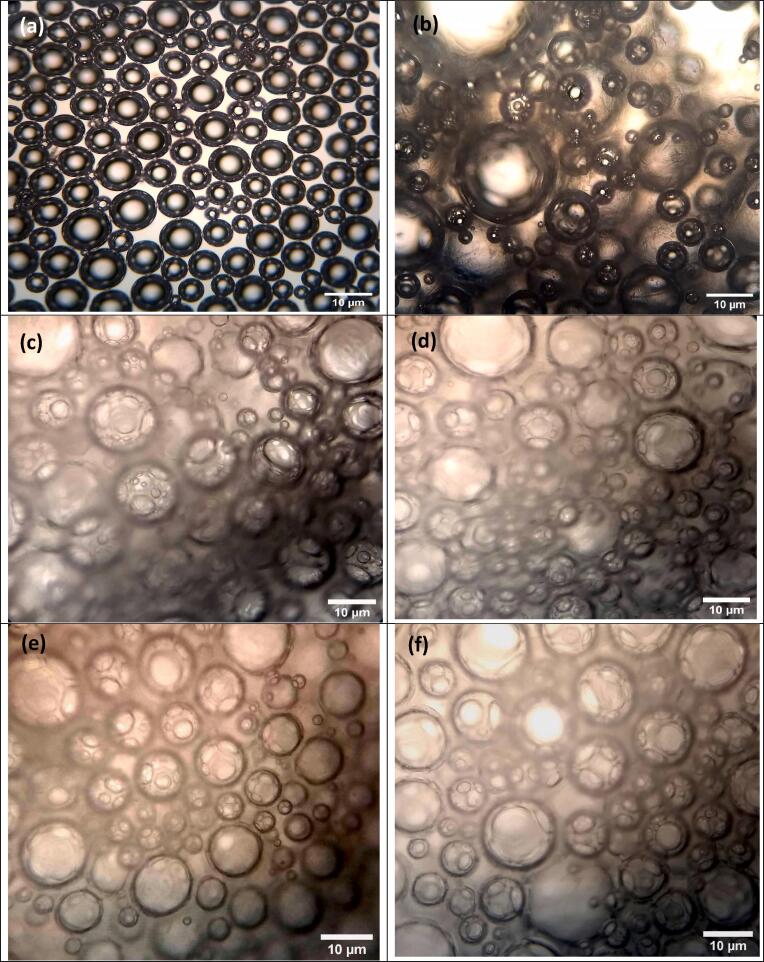

3.2.2. Optical microscopy

The morphology of individual biopolymers and complex coacervates is illustrated in Fig. 2 (a-k). WPI (Fig. 2a) showed spherical shape (0.2–1 μm), typical of globular proteins, where nonpolar groups were oriented inside and polar groups to the outside of the molecule [53]. The morphology of KC (Fig. 2b) corresponds to their molecular structure, it has a double helix conformation where the helical linear portions can be associated to form a three-dimensional network [54].

Fig. 2.

Optical microscopy (40x), morphology of: (a) WPI, (b) KC, (c) WPI-KC CC and WPI HIUS- KC CC: (d) 50% A, 2 min, (e) 50% A, 4 min, (f) 100% A, 2 min, (g) 100% A, 4 min.

On the other hand, complex coacervates control (Fig. 2c) had a completely different morphology than that of individual biopolymers, with spherical and defined shapes (2–3 μm), typical of coacervates, resulted from the interaction between both biopolymers. Also it is possible to observe macro complexes of bigger size (11–16 μm) resulting from the union of several individual complex coacervates (CC) [11].

The coacervated phase can be considered as a network of interconnected intrapolymeric complexes with contacts that are transiently stabilized by the association with protein molecules or as a heterogeneous network containing entangled and cross-linked protein and polysaccharide rich phases, both the protein and the polysaccharide are found at the interface of the coacervates, and its structural conformation influences coacervation [1]. Further, WPI HIUS pre-treatment had an influence in complex coacervation (Fig. 2d-2g). In this case, an increase in the HIUS treatment amplitude presented conformational changes in protein structure, which lead to different complexation with a trending to disintegrate the overall macro-complex (coacervate- coacervate) into individual coacervate forms [11].

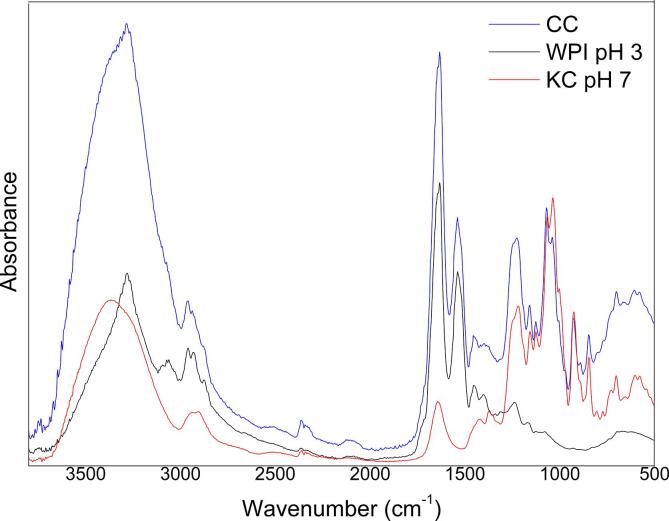

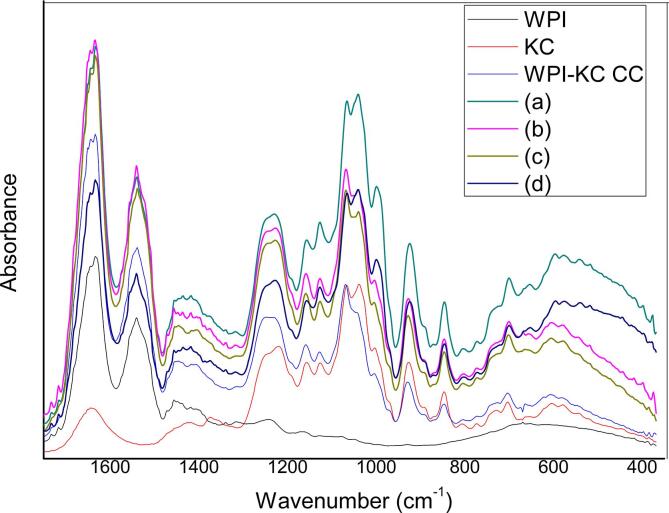

3.2.3. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR)

Fig. 3 shows the infrared spectra of both, individual biopolymers WPI, KC and WPI-KC complexes. WPI spectrum exhibited a strong absorption band at 3270 cm−1 corresponding to hydroxyl contraction vibrations attributed to hydrogen bonds of water. Further, at 3065 cm−1, there was a weak absorption that corresponds to stretching N–H vibration (amide B), the absorption band at 2955 cm−1 corresponds to stretching vibration of –CH. It is possible to observe on the fingerprint region (1800 to 900 cm−1) the vibrations of the characteristic protein groups, the broad bands in the spectrum centered at approximately 1640 cm−1 and 1520 cm−1 were associated with amide I (α-helix and β-sheet structures of proteins) and amide II (combined (N–H) and (C–N)) respectively, contributing to the peptide bond group vibrations of proteins. The band at approximately 1450 cm−1 resulted from the deformation bending of C–H bonds in the >CH2 groups and the band at 1390 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching of C = O in the –COO groups. The broad peak band ~1250 cm−1 corresponds to the signal of the amide III groups [42], [55], [56], [57].

Fig. 3.

FTIR-ATR spectra (4000–400 cm−1) of individual biopolymers, WPI, KC and WPI-KC CC.

On the other hand KC, presented its typical absorption bands at 847 and 926 cm−1 indicating the presence of D-galactose-4 sulfate and 3,6-anhydro-D galactose, molecular units of the KC [56], [57]. The vibration at 1041 cm−1 is attributed to the vibrations of the CO and C-OH bonds [57]; also, the adsorption band at 1077 cm−1 corresponds to the CO bond of 3,6 anhydrous D-galactose [56], [57].

Meanwhile CC spectra, presented the typical bands of absorption of WPI (1600–1700 cm−1) and KC (900–1400 cm−1). The possible electrostatic interactions between both biopolymers may be a visible inversion in the band that corresponds to the vibrations of the CO bond of the 3,6 Anhydrous-D-galactose (1041 cm−1) and the stretch CN bond of the primary protein amine (1077 cm−1). There was also a modification in the band shape at 1238 cm−1 that corresponds to the vibration of the SO bond of KC sulfate groups and the CN bond of the WPI primary amine. Other points of possible electrostatic interaction with visible changes (3283 cm−1 and 3366 cm−1) were those that correspond to the vibration of the NH bonds in the case of protein and OH in the case of KC [55], [58], these regions had very characteristic spectrum band profiles for proteins and polysaccharides. In the case of coacervates, a band of neither of the two characteristic bands was obtained, which could indicate a possible point of interaction [11], [58].

On the other hand, the FTIR-ATR absorption spectra for CC elaborated with HIUS-treated WPI are shown in Fig. 4. As the control, CC spectrum presented typical absorption bands of WPI (1600–1700 cm−1) and KC (900–1400 cm−1), the possible interactions between both biopolymers remains regardless of the HIUS treatment applied to WPI. Although differences were observed at 1041 and 1077 cm−1, independently of the ultrasonic treatment, there was a noticeable change in the shape of the band that corresponds to the vibrations of the CO bond of the 3,6 anhydrous-D-galactose and to the stretch CN bond of the primary protein amine, respectively. Another important change in the band shape was found at 1238 cm−1, corresponding to the asymmetric vibration of the sulfate groups of KC and the asymmetric vibration of the CN bond of WPI [42], [55], [57], [59]. There were also differences regarding CC control, in the region between 1400 and 1500 cm−1 corresponding to the vibrations of the carboxylate groups and C-OH vibrations [60]. In general terms, stability in the coacervate system is proportional to the number of interactions between the KC and the WPI, i.e. more interaction, greater stability [61]. The conformational changes presented in HIUS WPI, influenced the way in which both biopolymers interact electrostatically; however, the mainly groups involved in the CC interactions remains and were NH+, CN, –OH for WPI and, –COH, –COOH, –OH, –SO4 groups in the case of KC.

Fig. 4.

FTIR-ATR spectra (1600–400 cm−1) of individual biopolymers, WPI, KC and WPI HIUS pre-treated- KC CC: (a) 50% A, 2 min, (b) 50% A, 4 min, (c) 100% A, 2 min, (d) 100% A, 4 min.

As it is well known, HIUS implosions can cause extreme localized changes in temperature and pressure at the sites known as hot spots; in addition to all the already mentioned physical changes associated with cavitation, there are also selected chemical effects including the formation of free radicals by different sonochemical reactions that may affect aroma, taste, mouthfeel and technological features of foodstuffs [61], [62]. The behavior of proteins under sonication mainly depends on their structural complexity and on the type of dominant secondary structure present (α-helix or β-sheet) [27], [63]. It has been suggested that free radicals produced by water sonolysis, such as superoxides (H2O.) have an important role in in the modification of protein structures inducing disulfide crosslinking of protein molecules in aqueous medium [61]. However, in our scenario, the impact of free radicals is expected to be very mild. Short ultrasonic processing times (as those used in the present study) have been observed to cause a reduced free-radical formation and less pronounced related off flavors in food matrices [64]. Besides, the presence of KC could have helped to reduce any free radical-related damages in the sample. Sulphated polysaccharides extracted from brown and red seaweeds such as KC have been shown to inhibit the formation of free radicals and their sulphation degree was found to be directly related to their radical scavenging activity, with KC exhibiting mild antioxidant properties [65]. Consequently, the impact of free radicals in the WPI-KC complex coacervated systems was considered to be negligible.

3.3. Functional properties of WPI-KC complex systems

3.3.1. Rheology

The viscosity in dispersed proteins depends on different molecular properties such as size and shape, as well as their protein-solvent interactions, hydrodynamic volume and molecular flexibility in the hydrated state [62]. In the present study, changes in viscosity because of protein- polysaccharide interaction were desirable. CC presented a different viscosity level compared to individual biopolymers (Table 5), which represented the formation of a new structure. It is possible to observe a significant increase (~20 times) on CC viscosity (~20 mPa*s, 25 °C) compared to the WPI (1.16 ± 0.07 mPa*s, 25 °C). This increase in viscosity can be attributed to the formation of larger molecular entities due to complex coacervation, improving the viscoelastic properties of the system [1], [12]. Nevertheless, regardless the HIUS treatment applied, no significant changes (p < 0.05) on viscosity level of WPI and CC were detected.

Table 5.

WPI, KC and CC Viscosity (25 °C).

| HIUS treatment on WPI | Viscosity mPa*s (25 °C) |

CC adjustment, RMSE |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KC | WPI | CC | PL | HB | |

| – | 57.44 ± 1.17 | 1.16 ± 0.07a | 28.09 ± 1.17a | 1.71 | 0.06 |

| 50%A, 2 min | 1.17 ± 0.08a | 22.18 ± 2.13a | 0.15 | 0.03 | |

| 50%A, 4 min | 1.17 ± 0.05a | 30.39 ± 0.6a | 0.13 | 0.09 | |

| 100%A, 2 min | 1.24 ± 0.02a | 23.26 ± 4.20a | 0.11 | 0.06 | |

| 100%A, 4 min | 1.25 ± 0.04a | 23.01 ± 2.05a | 0.13 | 0.04 | |

Different letters in the same column present significant difference (p < 0.05).

PL = Power law.

HB = Herschel-Bulkley.

On the other hand, the rheological behavior of the coacervates is that of a pseudo plastic fluid, i.e., when shear speed increases, viscosity decreases. For this reason, CC viscosity was adjusted to the mathematic models used for pseudoplastic fluids: Power law (PL) and Herschel–Buckley (HB). According to the results, the HB model presented lower RMSE value than PL model; based on that, it was a better option to use as predictive equation for a rheological behavior model.

3.3.2. Foaming capacity

Several studies have shown that ultrasonic treatment can improve WPI foam stability [35], [67], however an excessive treatment could generate a drastic loss in the foaming ability, due to aggregation and polymerization induced by treatments [15]. In order to known the influence of HIUS on WPI-KC complex coacervation, foaming capacity was evaluated.

Foaming properties of proteins are determined by its molecular structure, HIUS could affect these properties by inducing conformational changes in the secondary, and tertiary structures, as well as changes in both; strong and weak bonds, including hydrogen bonds, and also on structures that have been demonstrated to determine the foaming properties such as, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic bonds and disulfide bonds [15]. In this work, according to the results of physicochemical characterization, through HIUS treatment, it was possible to increase surface hydrophobicity (Table 1), to reduce particle size (Table 2) and to induce changes on the structural conformation (Table 3) of WPI. The influence of these effects on the foaming capacity of WPI HIUS-KC complex coacervates, was evaluated through the following parameters: foam stability (%), volume increment or overrum (%) and foam expansion ability (%) (Table 6). HIUS treatment on WPI has a significant influence (p < 0.05), increasing foaming capacity as the amplitude and treatment time increase, i.e., the most intense treatments (100%, 2–4 min) produce more stable foams with a major expansion ability and overrun. These improvements in CC foaming capacity could be related with the partial denaturation of proteins resulting in molecular rearrangements that can lead to form thicker rigid interface films [41].

Table 6.

Complex coacervates foaming capacity.

| Sample | HIUS treatment on WPI | Foam stability (FS%) | Volume increment (VI%) | Foam expansion ability (FE%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WPI | – | 73.40 ± 2.27c | 75.00 ± 0.11c | 173.75 ± 1.44c |

| Complex coacervates | – | 71.17 ± 1.74c | 77.50 ± 2.04c | 177.5 ± 2.04c |

| 50%A, 2 min | 77.85 ± 1.71b | 126.56 ± 2.77b | 226.56 ± 2.77b | |

| 50%A, 4 min | 78.00 ± 1.29b | 125.63 ± 1.61b | 225.63 ± 1.61b | |

| 100%A, 2 min | 90.25 ± 1.26a | 147.81 ± 2.13a | 247.81 ± 2.13a | |

| 100% A, 4 min | 90.0 ± 0.82a | 148.75 ± 1.02a | 248.75 ± 1.02a |

Different letters in the same column present significant difference (p < 0.05).

Although there were improvements in foaming capacity due to HIUS, the use of KC is also a key factor in foam stability of CC, showing a synergistic effect, WPI is able to spread more rapidly in the air–water interface due to its high molecular flexibility, which results in a foam brittle and characterized by large pores [31]. The addition of KC resulted in higher foam stability, forming a thicker and more viscous film with the ability to retain air for longer periods of time. Protein must migrate to the air–water interface and unfold to expose hydrophobic groups towards the gaseous phase and hydrophilic groups to the aqueous phase to form a viscoelastic film around the air bubble. In this context, electrostatic complexation influences both diffusion of proteins into the interface and re-alignment once there [40]. Polysaccharides had no affinity for the air–water interface, but encourage protein–protein interactions, which lead to developed a multilayer cohesive protein film on the interface that prevents foam to collapse and allows more stable foams formation [31]. These interfacial networks also tend to show a ‘jamming effect’, which reduces foam drainage and maintains the structural integrity of the system [68].

Fig. 5 shows the optical microscopy structure of foams, it is important to notice that in all the treatments applied (Fig. 5b-5f), bubbles with spherical morphology and well-defined lamellae were produced, it is not possible to observe empty spaces between the air bubbles, which could contribute to enhanced foam stability, resulting in higher foaming capacity. By contrast, on the WPI foam the spaces between bubbles are visible (Fig. 5a) resulting in a not stable foam compared to CC. Electrostatic complexation is expected to influence both diffusion of proteins to the interface and re-alignment once there [40]. The use of KC and HIUS pretreated WPI, enhance the resistance against bubble collapse, forming stronger lamellas and adsorbed films [69].

Fig. 5.

Optical microscopy (10x), foams morphology of: (a) WPI, (b) WPI-KC CC, WPI HIUS- KC CC: (c) 50%A, 2 min, (d) 50%A, 4 min, (e) CC (100%A, 2 min), (f) CC (100%A, 4 min).

3.3.3. Emulsifying properties

Ultrasound treatment increases protein surface hydrophobicity due to the mechanical effects of cavitation, causing structural changes on α-helix and β-sheets, as a consequence, protein unfolding results, modifying the secondary and tertiary structures of the protein; internal hydrophobic regions of protein are unmasked, this resulted in a loosening of the protein folding and a consequent change in the emulsifying capacity of the protein [36], [50]. There are several studies that have reported the influence of sonication on emulsions, forming smaller droplets, decreasing interfacial tension, with significant increases in surface hydrophobicity, solubility, emulsifying activity index (EAI), and emulsifying stability index (ESI) [37].

According to the results, due to HIUS treatment there was a significant (p < 0.05) increase on EAI, ESI, and the stability of the emulsions (%), related to the induced conformational changes and the increase of WPI surface hydrophobicity [66] (Table 7). On the other hand, the effectiveness of KC influencing emulsifying properties of WPI seems to be related to the linear charge density of the carrageenan and possibly its conformation in solution [12]. During the emulsification process, protein-polysaccharide complexes migrate to the oil–water interface and then realign to form viscoelastic films around the oil bubbles, where the hydrophobic groups of protein were oriented to the oil phase and the hydrophilic groups of polysaccharide to the aqueous [40].

Table 7.

Emulsifying properties of complex coacervates.

| Sample | HIUS treatment on WPI | EAI (m2/g) (25 °C) | ESI (min) | ES (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h | 1 week | 1 month | ||||

| WPI | – | 3.65 ± 0.27f | 3.19 ± 0.16c | 100.0 ± 0.0a | 90.0 ± 0.0b | 25.0 ± 1.0e |

| Complex Coacervates | – | 14.15 ± 0.20e | 19.95 ± 1.05b | 100.0 ± 0.0a | 100.0 ± 0.0a | 76.25 ± 1.77b |

| 50%A, 2 min | 22.55 ± 0.41d | 36.17 ± 0.92a | 63.75 ± 1.77b | 63.75 ± 1.77c | 68.12 ± 0.88c | |

| 50%A, 4 min | 37.76 ± 0.61c | 31.55 ± 0.87a | 65.00 ± 3.54b | 63.75 ± 3.54c | 48.75 ± 1.77d | |

| 100%A, 2 min | 47.40 ± 0.54a | 34.65 ± 1.5a | 100.0 ± 0.0a | 100.0 ± 0.0a | 100.0 ± 0.0a | |

| 100% A, 4 min | 40.49 ± 0.41b | 36.0 ± 1.29a | 100.0 ± 0.0a | 88.75 ± 0.0b | 80.62 ± 0.88b | |

Different letters in the same column present significant difference (p < 0.05).

EAI = emulsifying activity index

ESI = emulsifying stability index.

ES = emulsion stability, 100% means no phase separation.

The percentage of emulsion stability relates the degree of emulsion breakdown over a defined time period, after one month the emulsion corresponding to CC: WPI treated by 100% amplitude, 2 min remains without phase separation, being a significant difference (p < 0.05) between this treatment and the other applied. The increase in WPI emulsion stability when is complexed with carrageenan may be due to charge repulsion between droplets, viscoelastic film formation with protein–polysaccharide complexes saturating the oil–water interface, steric stabilization caused by the carrageenan chains and an increase in the viscosity of the continuous phase [51].

3.3.4. Solubility determination

HIUS treatment did not presented a significant (p < 0.05) influence on the solubility of the samples (~90%) (Table 8). The polysaccharide seems to inhibit protein–protein interactions resulting from a treatment that affects protein structure, in which solubility is likely to be lost, i.e., the complexation between proteins and sulfated polysaccharides resulted in protection against the loss of solubility, by blocking the protein hydrophobic sites [40], [70].

Table 8.

Complex coacervates solubility determination.

| Sample | HIUS treatment on WPI | Solubility (%) (25 °C) |

|---|---|---|

| WPI | – | 95.5 ± 0.707a |

| Complex Coacervates | 50%A, 2 min | 95.0 ± 1.41a |

| 50%A, 4 min | 92.5 ± 3.54a | |

| 100%A, 2 min | 93.5 ± 4.95a | |

| 100% A, 4 min | 92.5 ± 2.12a |

Different letters in the same column present significant difference (p < 0.05).

3.3.5. Gelation properties

Although both biopolymers, individually, have gelling properties, after gelling procedure, none of CC systems could form a gel. Above 60 °C, temperature required for WPI gelation, a separation between WPI-KC occurred (data not shown). The physicochemical properties of proteins and polysaccharides are influenced by temperature. Polysaccharide and protein complex formation is mainly driven by various non-covalent interactions, like electrostatic, H-bonding, hydrophobic, and steric interactions; the extent of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction depends on temperature [71]. Hydrogen bonding is a moderately strong bond, which becomes relatively insignificant at high temperature, these bonds are ionic in nature and refer to the interaction between hydrogen atoms attached to an electronegative atom (oxygen, sulfur) and other electronegative atom (the sulfur of sulfate group), a classic example of hydrogen bonding has been shown in the complex coacervation [2]. In this case, complex coacervation was lost with the increase in temperature, which is in agreement with the FTIR results (Fig. 3, Fig. 4) where an electrostatic interaction between both biopolymers was observed.

3.3.6. Application of WPI-KC complex systems based on their functional properties

Whey proteins have been used as an additive to formulate products rich in protein and / or low in lactose, also by its improved biological value, conferred by its content in bioactive peptides with biological properties, such as antihypertensive, antioxidant, antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activities and also because of its functional properties such as, gelling, foaming and emulsification [4], [72]. Based on this, it is feasible to apply whey protein as a functional ingredient with bioactive properties; in this sense, complex coacervates represent an important tool for food manufacturers to enhance food quality and even nutritional attributes [1], [51]. Rheological properties as well as interfacial properties in emulsions and foams are the prerequisite for the successful use of protein- polysaccharide mixed systems [1]. Nowadays, in fermented dairy products, such as sour milk and yogurt drinks, CC represent a powerful tool to modulate viscosity and heat stability by associative interactions, also have been used to produce meat analogs and fat substitutes or replacers. Applications as texturing agents include protein- polysaccharide core–shell microparticles utilized as a cream or fat substitute. CC also have been utilized as structuring agents with the capacity to bind and/or structure water in low-fat confectionery products and to stabilize interfaces in products such as mayonnaises and foamed emulsions [1]. Although proteins are efficient emulsifiers, do not produce emulsions that are stable under broad environmental conditions (e.g., pH, ionic strength, etc.); as Krempel et, al. suggest, many studies have proposed using polysaccharide-protein complexes as alternative sources for gum arabic or modified starches in beverage emulsions [73], [74]. Fundamental understanding of the interactions at the molecular and colloidal levels will provide a strong basis to exploit the physical functionality of such complex systems in different applications (e.g. microencapsulation technology, imparting specific sensory characteristics, time/temperature/pH/ionic control-release, emulsion stability, etc. [2]. Finally, studies in complex food systems are still needed to assess food applications; however, the initial results offer promising behavior in several products, such as sherbet and aerated foams obtained from acidic dairy products [1].

4. Conclusions

Although complex coacervation has been widely described, the use of HIUS technique helped to improve some of its functional properties. According to FTIR-ATR spectra analysis, complex coacervation was carried out through multiple electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonds, given as a result, spherical and defined forms, that were visualized by optical microscopy. Deconvolution analysis suggest, that WPI structure was modified by HIUS treatments and surface hydrophobicity increased, meanwhile OD and particle size decrease. The treatment with the highest increase in disordered structures and β-sheets, hydrophobicity and therefore better functional properties (foaming and emulsifying) was the treatment at amplitude of 100%, 2 min. CC produced with WPI HIUS treated could increase the foaming capacity, the stability of emulsions, add viscosity and maintain their solubility. Based on this, the HIUS and KC complex coacervation is an effective tool to improve WPI functional properties, which creates a huge gap in the successful application of the CC system, as an ingredient of high value to the food industry.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sara A. Vargas: Investigation, Writing - original draft. : . R.J. Delgado-Macuil: Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. H. Ruiz-Espinosa: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Methodology. M. Rojas-López: Methodology, Formal analysis. G.G. Amador-Espejo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this research was provided by the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology (through scholarship support 577084, grant CONACyT 254412), Instituto Politécnico Nacional (SIP). The authors kindly acknowledge Ingredion Mexico for providing the kappa carrageenan employed in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105340.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.S.L. Turgeon, S.I. Laneuville, Protein + Polysaccharide Coacervates and Complexes. From Scientific Background to their Application as Functional Ingredients in Food Products, First Edit, Elsevier Inc., 2009. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-374195-0.00011-2.

- 2.K.K.T. Goh, A. Sarkar, H. Singh, Chapter 12 - {Milk} protein–polysaccharide interactions, Milk {Proteins}. (2008) 347–376. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012374039700012X.

- 3.Moschakis T., Biliaderis C.G. Biopolymer-based coacervates: structures, functionality and applications in food products. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;28:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2017.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Castro R.J.S., Domingues M.A.F., Ohara A., Okuro P.K., dos Santos J.G., Brexó R.P., Sato H.H. Whey protein as a key component in food systems: physicochemical properties, production technologies and applications. Food Struct. 2017;14:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.foostr.2017.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.S.R. Derkach, N.G. Voron’ko, Y.A. Kuchina, D.S. Kolotova, A.M. Gordeeva, D.A. Faizullin, Y.A. Gusev, Y.F. Zuev, O.N. Makshakova, Molecular structure and properties of κ-carrageenan-gelatin gels, Carbohydr. Polym. 197 (2018) 66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Scholten E., Moschakis T., Biliaderis C.G. Biopolymer composites for engineering food structures to control product functionality. Food Struct. 2014;1:39–54. doi: 10.1016/j.foostr.2013.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asghari A.K., Norton I., Mills T., Sadd P., Spyropoulos F. Interfacial and foaming characterisation of mixed protein-starch particle systems for food-foam applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;53:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palanisamy M., Töpfl S., Aganovic K., Berger R.G. Influence of iota carrageenan addition on the properties of soya protein meat analogues. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2018;87:546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.09.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez-García Y.I., García-Vega K.S., Leal-Ramos M.Y., Salmeron I., Gutiérrez-Méndez N. Ultrasound-assisted crystallization of lactose in the presence of whey proteins and κ-carrageenan. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:714–722. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zia K.M., Tabasum S., Nasif M., Sultan N., Aslam N., Noreen A., Zuber M. A review on synthesis, properties and applications of natural polymer based carrageenan blends and composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;96:282–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Martínez D.A., Carrillo-Navas H., Barrera-Díaz C.E., Martínez-Vargas S.L., Alvarez-Ramírez J., Pérez-Alonso C. Characterization of a novel complex coacervate based on whey protein isolate-tamarind seed mucilage. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;72:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam R.S.H., Nickerson M.T. The properties of whey protein-carrageenan mixtures during the formation of electrostatic coupled biopolymer and emulsion gels. Food Res. Int. 2014;66:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitt C., Bovay C., Rouvet M. Bulk self-aggregation drives foam stabilization properties of whey protein microgels. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;42:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.P.L.H.F.P.F. McSweeney, Advanced dairy chemistry. Volume 1. Proteins: basic aspects, 2013. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- 15.Nicorescu I., Loisel C., Riaublanc A., Vial C., Djelveh G., Cuvelier G., Legrand J. Effect of dynamic heat treatment on the physical properties of whey protein foams. Food Hydrocoll. 2009;23:1209–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2008.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.H. Deeth, N. Bansal, Whey proteins, Elsevier Inc., 2018. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-812124-5.00001-1.

- 17.Vera A., Tapia C., Abugoch L. Effect of high-intensity ultrasound treatment in combination with transglutaminase and nanoparticles on structural, mechanical, and physicochemical properties of quinoa proteins/chitosan edible films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;144:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frydenberg R.P., Hammershøj M., Andersen U., Greve M.T., Wiking L. Protein denaturation of whey protein isolates (WPIs) induced by high intensity ultrasound during heat gelation. Food Chem. 2016;192:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosseini S.M.H., Emam-Djomeh Z., Razavi S.H., Moosavi-Movahedi A.A., Saboury A.A., Atri M.S., Van der Meeren P. β-Lactoglobulin-sodium alginate interaction as affected by polysaccharide depolymerization using high intensity ultrasound. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;32:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen X., Zhao C., Guo M. Effects of high intensity ultrasound on acid-induced gelation properties of whey protein gel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;39:810–815. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandrapala J., Zisu B., Kentish S., Ashokkumar M. The effects of high-intensity ultrasound on the structural and functional properties of α-Lactalbumin, β-Lactoglobulin and their mixtures. Food Res. Int. 2012;48:940–943. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jambrak A.R., Mason T.J., Lelas V., Paniwnyk L., Herceg Z. Effect of ultrasound treatment on particle size and molecular weight of whey proteins. J. Food Eng. 2014;121:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Sullivan J., Murray B., Flynn C., Norton I. The effect of ultrasound treatment on the structural, physical and emulsifying properties of animal and vegetable proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;53:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren X., Hou T., Liang Q., Zhang X., Hu D., Xu B., Chen X., Chalamaiah M., Ma H. Effects of frequency ultrasound on the properties of zein-chitosan complex coacervation for resveratrol encapsulation. Food Chem. 2019;279:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albano K.M., Nicoletti V.R. Ultrasound impact on whey protein concentrate-pectin complexes and in the O/W emulsions with low oil soybean content stabilization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;41:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.S.E. Kentish, Engineering Principles of Ultrasound Technology, Elsevier Inc., 2017. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804581-7.00001-4.

- 27.Chandrapala J., Zisu B., Palmer M., Kentish S., Ashokkumar M. Effects of ultrasound on the thermal and structural characteristics of proteins in reconstituted whey protein concentrate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18:951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barth A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta – Bioenerg. 2007;1767:1073–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R.S. Diniz, J.S. dos R. Coimbra, Á.V.N. de C. Teixeira, A.R. da Costa, I.J.B. Santos, G.C. Bressan, A.M. da Cruz Rodrigues, L.H.M. da Silva, Production, characterization and foamability of α-lactalbumin/glycomacropeptide supramolecular structures, Food Res. Int. 64 (2014) 157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Rocha-Selmi G.A., Bozza F.T., Thomazini M., Bolini H.M.A., Fávaro-Trindade C.S. Microencapsulation of aspartame by double emulsion followed by complex coacervation to provide protection and prolong sweetness. Food Chem. 2013;139:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herceg Z., Režek A., Lelas V., Krešić G., Franetović M. Effect of carbohydrates on the emulsifying, foaming and freezing properties of whey protein suspensions. J. Food Eng. 2007;79:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.01.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen X., Fang T., Gao F., Guo M. Effects of ultrasound treatment on physicochemical and emulsifying properties of whey proteins pre- and post-thermal aggregation. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;63:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R.S.H. Lam, Tailoring of whey protein isolate stabilized oil-water interfaces for improved emulsification, (2014).

- 34.Montellano Duran N., Spelzini D., Boeris V. Characterization of acid – Induced gels of quinoa proteins and carrageenan. Lwt. 2019;108:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.03.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao H., Ma L., Li T., Sun D., Hou J., Li A., Jiang Z. Impact of ultrasonic power on the structure and emulsifying properties of whey protein isolate under various pH conditions. Process Biochem. 2019;81:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2019.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojha K.S., Tiwari B.K., O’Donnell C.P. Effect of ultrasound technology on food and nutritional quality. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018;84:207–240. doi: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Režek Jambrak A. Physical properties of sonicated products: a new era for novel ingredients. Ultrasound Adv. Food Process. Preserv. 2017:237–265. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804581-7.00010-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.P.K. Singh, T. Huppertz, Effect of nonthermal processing on milk protein interactions and functionality, 3rd ed., Elsevier Inc., 2020. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-815251-5.00008-6.

- 39.Hosseini S.M.H., Emam-Djomeh Z., Razavi S.H., Moosavi-Movahedi A.A., Saboury A.A., Mohammadifar M.A., Farahnaky A., Atri M.S., Van Der Meeren P. Complex coacervation of β-lactoglobulin – κ-carrageenan aqueous mixtures as affected by polysaccharide sonication. Food Chem. 2013;141:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone A.K., Cheung L., Chang C., Nickerson M.T. Formation and functionality of soluble and insoluble electrostatic complexes within mixtures of canola protein isolate and (κ-, ι- and λ-type) carrageenan. Food Res. Int. 2013;54:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.A. Kilara, M.N. Vaghela, Whey proteins, Second Edi, Elsevier Ltd., 2018. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-100722-8.00005-X.

- 42.Wang C., Jiang L., Wei D., Li Y., Sui X., Wang Z., Li D. Effect of secondary structure determined by FTIR spectra on surface hydrophobicity of soybean protein isolate. Procedia Eng. 2011;15:4819–4827. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2011.08.900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reeb J., Rost B. Secondary structure prediction. Encycl. Bioinforma. Comput. Biol. ABC Bioinforma. 2018;1–3:488–496. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20267-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.L. Skipper, Traditional Methods of Sequence Determination Physiological Samples Foods, Elsevier Ltd. (2005) 344–352. doi: 10.5040/9780755699179.0007.

- 45.P. Sneha, C.G. Priya Doss, Molecular Dynamics: New Frontier in Personalized Medicine, 1st ed., Elsevier Inc., 2016. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Sow L.C., Nicole Chong J.M., Liao Q.X., Yang H. Effects of κ-carrageenan on the structure and rheological properties of fish gelatin. J. Food Eng. 2018;239:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.T. Wang, The Authentication of Whey Protein Powder Ingredients and Understanding Factors Regulating Astringency in Acidic Whey Protein Beverages to Estimate Astringency by Infrared Spectroscopy – An Instrumental Approach, Thesis. (2014) 1–134. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- 48.Liu J., Shim Y.Y., Shen J., Wang Y., Reaney M.J.T. Whey protein isolate and flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) gum electrostatic coacervates: turbidity and rheology. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;64:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.M. Boland, N. Zealand, Whey protein, Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2008. doi: 10.1533/9780857093639.30.

- 50.H.B. Wijayanti, A. Brodkorb, S.A. Hogan, E.G. Murphy, Thermal denaturation, aggregation, and methods of prevention, Elsevier Inc., 2018. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-812124-5.00006-0.

- 51.Stone A.K., Nickerson M.T. Formation and functionality of whey protein isolate-(kappa-, iota-, and lambda-type) carrageenan electrostatic complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2012;27:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martini S., Potter R., Walsh M.K. Optimizing the use of power ultrasound to decrease turbidity in whey protein suspensions. Food Res. Int. 2010;43:2444–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.A. Thompson, M. Boland, H. Singh, Milk Proteins: from Expression to Food, 2008. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-374039-7.00001-5.

- 54.Tavassoli-Kafrani E., Shekarchizadeh H., Masoudpour-Behabadi M. Development of edible films and coatings from alginates and carrageenans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;137:360–374. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D.L. Pavia, G.M. Lampman, G.S. Kriz, J.R. Vyvyan, Introduction to spectroscopy. 4th edition, Cengage Le, Belmont, 2009. https://books.google.com.mx/books?id=FkaNOdwk0FQC&printsec=frontcover&hl=es&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- 56.Pereira L., Amado A.M., Critchley A.T., van de Velde F., Ribeiro-Claro P.J.A. Identification of selected seaweed polysaccharides (phycocolloids) by vibrational spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR and FT-Raman) Food Hydrocoll. 2009;23:1903–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2008.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soares S.F., Trindade T., Daniel-Da-Silva A.L. Carrageenan-silica hybrid nanoparticles prepared by a non-emulsion method. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015;2015:4588–4594. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201500450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coates J. Interpretation of infrared spectra, a practical approach. Encycl. Anal. Chem. 2006:1–23. doi: 10.1002/9780470027318.a5606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.P. (California S.P.U. Beauchamp, Infrared Tables (short summary of common absorption frequencies) organic compounds, Spectrosc. Tables. 2620 (n.d.) 1–15. http://www.cpp.edu/~psbeauchamp/pdf/spec_ir_nmr_spectra _tables.pdf.

- 60.Venegas-Sanchez J.A., Tagaya M., Kobayashi T. Effect of ultrasound on the aqueous viscosity of several water-soluble polymers. Polym. J. 2013;45:1224–1233. doi: 10.1038/pj.2013.47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D. Bermudez-Aguirre, Sonochemistry of Foods, Elsevier Inc., 2017. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804581-7.00005-1.

- 62.A.S. Peshkovsky, From Research to Production: Overcoming Scale-Up Limitations of Ultrasonic Processing, Elsevier Inc., 2017. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804581-7.00017-8.

- 63.Awad T.S., Moharram H.A., Shaltout O.E., Asker D., Youssef M.M. Applications of ultrasound in analysis, processing and quality control of food: a review. Food Res. Int. 2012;48:410–427. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riener J., Noci F., Cronin D.A., Morgan D.J., Lyng J.G. Characterisation of volatile compounds generated in milk by high intensity ultrasound. Inter Dairy J. 2009;19(4):269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2008.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alexa R.I., Mounsey J.S., O’Kennedy B.T., Jacquier J.C. Effect of κ-carrageenan on rheological properties, microstructure, texture and oxidative stability of water-in-oil spreads. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2010;43:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.M. Dissanayake, Modulation of Functional Properties of Whey Proteins by Microparticulation, (2011).

- 67.Shen Y.R., Kuo M.I. Effects of different carrageenan types on the rheological and water-holding properties of tofu. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2017;78:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.12.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.N. Nayak, H. Singh, Milk protein-polysaccharide interactions in food systems, Elsevier, 2018. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.21472-8.

- 69.Martínez-Velasco A., Lobato-Calleros C., Hernández-Rodríguez B.E., Román-Guerrero A., Alvarez-Ramirez J., Vernon-Carter E.J. High intensity ultrasound treatment of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) protein: Effect on surface properties, foaming ability and structural changes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;44:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.F. Weinbreck, Whey protein / polysaccharide coacervates: structure and dynamics, The Netherlands Photography, 2004.

- 71.A.K. Gosh, P. Bandyopadhyay, Polysaccharide-Protein Interactions and Their Relevance in Food Colloids, in: The Complex World of Polysaccharides, InTech, 2012. doi: 10.5772/50561.

- 72.R.A. Khaire, P.R. Gogate, Whey Proteins, Elsevier Inc., 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816695-6.00007-6.

- 73.M. Krempel, K. Griffin, H. Khouryieh, Hydrocolloids as emulsifiers and stabilizers in beverage preservation, Elsevier Inc., 2019. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-816685-7.00013-6.

- 74.Zhang J., Peppard T.L., Reineccius G.A. Double-layered emulsions as beverage clouding agents. Flavour Fragr. J. 2015;30:218–223. doi: 10.1002/ffj.3231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.