Abstract

Patient engagement (PE) has become embedded in discussions about health service planning and quality improvement, and the goal has been to find ways to observe the potential beneficial outcomes associated with PE. Patients and health care professionals use various terms to depict PE, for example, partnership and collaboration. Similarly, tokenism is consistently used to describe PE that has gone wrong. There is a lack of clarity, however, on the meanings and implications of tokenism on PE activities. The objective of this concept analysis was to examine the peer-reviewed and gray literature that has discussed tokenism to identify how we currently understand and use the concept. This review discusses 4 dimensions of tokenism: unequal power, limited impact, ulterior motives, and opposite of meaningful PE. These dimensions explicate the different components, meanings, and implications of tokenism in PE practice. The findings of this review emphasize how tokenism is primarily perceived as negative by supporters of PE, but this attribution depends on patients’ preferences for engagement. In addition, this review compares the dimensions of tokenism with the levels of engagement in the International Association of the Public Participation spectrum. This review suggests that there are 2 gradations of tokenism; while tokenism represents unequal power relationships in favor of health care professionals, this may lead to either limited or no meaningful change or change that is primarily aligned with the personal and professional goals of clinicians, managers, and decision-makers.

Keywords: patient engagement, tokenism, meaningful engagement, patient perspectives/narratives, concept analysis, content analysis, qualitative methods, qualitative evidence synthesis

Introduction

Patient engagement (PE) has become embedded in discussions about health service planning and quality improvement. Multiple research studies have examined the determinants, processes, and mechanisms of PE and how it can improve the quality of care (1). There is an increasing understanding that PE can have important implications for patients, clinicians, and health systems. Broadly, it can promote the participation of a wider group of individuals in activities that were originally within the purview of health care professional responsibility. PE can also enhance quality of life, accountability in health care professionals, and efficiency of health systems (2 –4). These ethical imperatives and organizational and patient benefits contribute to a strong rationale for including patients across the milieu of health care.

Policy pressures to engage patients have been driven by the need to observe the potential positive outcomes associated with PE. However, there is an emerging understanding that these outcomes are only possible when patients engage meaningfully in all health care activities. Previous research has found that although patients engage in a variety of activities, there are a lack of methods, mechanisms, and approaches to meaningful engagement (5,6). Meaningful PE is a nebulous concept that previous syntheses have attempted to clarify. A recently published review described how patients and health care professionals conceptualize different synonyms of meaningful PE: collaboration, cooperation, coproduction, active involvement, partnership, and consumer and peer leadership (7). This review found that although these terms are regularly used by patients, clinicians, and managers in practice, there is a considerable amount of overlap and muddling between them, which may create confusion, misrepresentation, and miscommunication about expectations and processes of engagement (7).

In contrast to meaningful PE, there is another concept that is used commonly by PE practitioners to depict what PE should not be. Originally arising from Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation (8), tokenism has become the de facto concept depicting when PE has gone wrong. According to Arnstein, tokenism exists when there are unequal power relations that cause citizens to have a circumscribed role in decision-making (8). Health service organizations are especially susceptible to tokenism because of the natural power differences that exist between patients and health care professionals. Although patients regularly engage in multiple health care activities today, there is some research indicating that their engagement is tokenistic (9); intended to achieve the personal or professional objectives of health care professionals rather than support health system redesign to be more aligned with patient and family expectations, needs, and preferences (10). For example, research has shown that some health care professionals prefer to recruit patients who they perceive to be compatible with their quality improvement goals and philosophies (11). On the other hand, tokenism can exist in clinical care when health care teams make decisions in the presence of patients but without the opportunity to voice their concerns about treatment options. Tokenism can also have adverse outcomes on health care practice. For instance, if it is true that the potential beneficial outcomes associated with PE will only be observed when it is meaningful, then constrained health care resources are squandered to achieve tokenistic PE (12). This reflection reinforces the importance of ensuring that PE processes are meaningful and not tokenistic in nature.

Practitioners need to be equipped with the resources to identify, appraise, and address tokenistic PE. This requires an understanding of the various conceptualizations of tokenism; however, there is a lack of clarity surrounding the dimensions of this concept. The objective of this review is to examine the peer-reviewed and gray literature that has discussed tokenism to identify how we currently understand and use the concept in PE practice. The goal is to formulate a preliminary set of dimensions for tokenism that could inform the practice and policy of PE in health care activities.

Methods

Approach

Since the objective of this review was to explore how “tokenism” had been conceptualized in the PE literature, a content analysis was deemed appropriate. Qualitative content analysis derives categories and themes of a particular phenomenon from a close analysis of text (13). Qualitative content analysis is a versatile and adaptable method that identifies the connotations and denotations of language while at the same time examines its contextual meaning (14,15). This approach was used to conduct a concept analysis of tokenism within peer-reviewed and gray literature. The overall goal was to formulate a preliminary set of dimensions for tokenism based on how authors have framed the concept in the literature.

Literature Search

A database and gray literature search were conducted to retrieve all publications that discussed tokenism as a primary topic or objective. All articles included in this review are referred to as publications to be inclusive of both peer-reviewed and nonpeer-reviewed knowledge products. Table 1 summarizes the search strategies.

Table 1.

Summary of Search Strategies Conducted on April 20, 2019.

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Database |

|

| Handsearching of journals |

|

| Gray literature |

|

| References Lists |

|

Abbreviation: PE, patient engagement.

Screening

The goal of screening was to find studies that discussed tokenism as a primary topic within the context of PE in health care activities. A previous review’s categorization of PE health care activities was used as a starting point for this analysis (16). Publications were excluded if they discussed tokenism as a secondary or peripheral topic, for example, as a finding of a broader research objective. Table 2 summarizes the eligibility criteria of this review.

Table 2.

Summary of Eligibility Criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

Abbreviation: PE, patient engagement.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The descriptive characteristics of included articles were extracted including author, year of publication, title of publication, journal or source of publication, objectives, country, design or type of publication (ie, peer-reviewed paper, qualitative, quantitative, editorial, blog, essay, and so on), number and type of participants (if available), PE context or health care activity, definitions and conceptualizations of tokenism, and the main findings or arguments. Patient engagement context or health care activity categorizations were informed by a previous review on this topic that delineated 4 categories: clinical care, research, priority setting, and organizational activities (16). These categories of health care activities are distinct bodies of research in the PE literature with different theories and frameworks. For example, PE in research is distinct from PE in clinical care on the roles that patients and family play (eg, research question development vs self-management strategies) as well as the most effective and appropriate resources needed to improve meaningful PE (eg, providing academic literature on the research versus informing patients of all treatment options and their pros and cons). For this reason, it was helpful to examine how tokenism has been applied between health care activities. However, due to the lack of literature overall, this review focused on presenting a holistic and integrated summary of tokenism across all health care activities.

Summative content analysis has been described as the most appropriate analytic framework for examining manuscripts and documents for meaning (17). Included publications often did not clearly define tokenism or a theoretical framework that guided their conceptualization. As such, summative content analysis was used to derive implicit understandings of tokenism within authors’ discussions of the concept. This process involved appraising the context surrounding the use of “tokenism” as well as comparing how the concept has been employed in different types of documents. An inductive thematic analysis was also performed. This process involved reviewing 5 publications to formulate a preliminary coding schema with themes, categories, and dimensions representative of the concept. The preliminary coding schema was applied to the remainder of publications and modified iteratively to capture the dimensions of included literature.

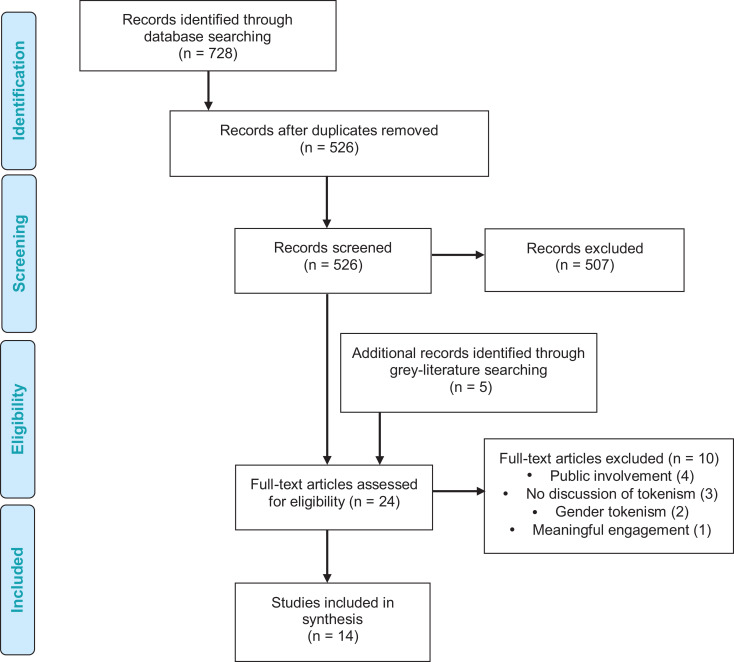

Results

Database searching found 728 hits, and after removing duplicates, 526 went through initial screening. After initial screening, 507 hits were excluded and 19 publications underwent full-text screening. Of these, 11 were included. Handsearching and gray literature searching found 5 results, 3 of which were eligible. In total, 14 publications were included in this analysis (10,13,18 –29). Figure 1 shows the screening and selection process for this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Adapted from Moher et al. (30).

Descriptive Characteristics

Table 3 summarizes the types of included publications, Table 4 summarizes the countries where included publications were published, Table 5 summarizes the PE contexts and health care activities represented in included publications, and Table 6 provides the descriptive characteristics of all publications.

Table 3.

Summary of Types of Included Publications.

| Type of publication | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Commentaries published in academic journals (12,20,21,24,29) | 5 (35.7%) |

| Blogs (19,22,27,28) | 4 (28.6%) |

| Primary qualitative studies (10,18,25) | 3 (21.5%) |

| Secondary analysis of primary qualitative data (23) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Review (26) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Total number of included articles | 14 (100%) |

Table 4.

Summary of Countries of Included Publications.

Table 5.

Topics of PE in Included Publications.a

| PE context/Health care activity | Count (proportion) |

|---|---|

| Organizational activities (12,18,21 –23,25,26,28,29) | 9 (64.3%) ˆ Planning (21 –23,25,28,29): 6 (42.9%) ˆ Quality improvement (12,21,22,26,28): 5 (35.7%) ˆ Service delivery (22,25): 2 (14.3%) |

| Research (10,20,29) | 3 (21.4%) |

| Clinical care (19) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Medical education (24) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Drug Development (27) | 1 (7.1%) |

Abbreviation: PE, patient engagement.

a One article explicitly discussed both research and organizational activities (29). Therefore, the total number of articles in this table do not add to the number of included articles in this study.

Table 6.

Descriptive Characteristics of Included Publications.

| Author, year and title | Objectives | Country | Type of publication | PE context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bess et al, 2009 (18) Participatory organizational change in community-based health and human services: from tokenism to political engagement |

Present a comparative case study of 2 organizations involved in such a process (ie, to address collective wellness, human service organizations’ need to challenge their current paradigm, attend to the social justice needs of community, and engage community participation in a new way, and in doing so become more openly political) through an action research project aimed at transforming the organizations’ managerial and practice paradigm from one based on first-order, ameliorative change to one that promotes second-order, transformative change via strength-based approaches, primary prevention, empowerment and participation, and focuses on changing community conditions | United States | Case study | Organizational activities—planning, delivery, evaluation, and improvement |

| Buckley and Hutson, 2004 (19) User involvement in care: avoiding tokenism and achieving partnership |

NR | United Kingdom | Blog | Clinical Care |

| Dewar (2005) (20) Beyond tokenistic involvement of older people in research: a framework for future development and understanding |

Describe developments to support involvement of older people through work at the Royal Bank of Scotland Centre for the Older Person’s Agenda Identify a number of challenges that this has raised for researchers |

United Kingdom | Commentary | Research |

| Farrington (2016) (21) Co-designing healthcare systems: between transformation and tokenism |

NR | United Kingdom | Commentary | Organizational activities—planning and improvement |

| Glauser (2016) (22) Beyond tokenism: how hospitals are getting more out of patient engagement |

NR | Canada | Blog | Organizational activities—planning, delivery, evaluation, and improvement |

| Hahn (2017) (10) Tokenism in patient engagement |

Explore how tokenism might influence engaging patients in research to help researchers work towards more genuine engagement | United States | Primary qualitative not specified | Research |

| Hiebert (2018) (23) Tokenism and mending fences: how rural male farmers and their health needs are discussed in health policy and planning documents |

Examine how rural male framers and their health needs are discussed in Ontario rural health policy documents | Canada | Primary content analysis | Organizational activities—planning |

| Majid (2018) (12) What have we done? The piths and perils of tokenistic engagement in healthcare |

Revisit the reasons that originally catalyzed the patient engagement movement; examine the processes that have led to the state of the art of patient engagement today | Canada | Commentary | Organizational activities—improvement |

| McCutcheon (2014) (24) Service-user involvement in nurse education: partnership or tokenism? |

Discuss the health policy background and the current approaches taken in the involvement of service users in healthcare education |

United Kingdom | Commentary | Health professions education |

| Nestor (2008) (25) The employment of consumers in mental health services: politically correct tokenism or genuinely useful? |

Examine the role of consumers as service providers Describe the successful employment of peer support workers in a public mental health service |

Australia | Case study | Organizational activities—planning and delivery |

| Ocloo (2016) (26) From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement |

Review a range of arguments and methods about the benefits and difficulties with involvement and discussed conclusions | United Kingdom | Review | Organizational activities—improvement |

| Pharmletter (2019) (27) Parexel’s Alberto Grignolo on patient engagement: from tokenism to telling contributions |

NR | United States | Blog | Drug development |

| Robins (2014) (28) 10 ways patient engagement in Canada smacks of tokenism |

NR | Canada | Blog | Organizational activities—planning and improvement |

| Supple (2015) (29) From tokenism to meaningful engagement: best practices in patient involvement in an EU project |

Talks about patient involvement in one of the biggest EU projects to date Describes how people and carers of people with asthma have been able to develop and drive input and have their voice heard among the >200 health care professional project members |

United Kingdom | Commentary | Research and organizational activities—planning |

Abbreviations: EU, European Union; NR, not reported; PE, patient engagement.

Dimensions of Tokenism

This section illustrates how tokenism has been depicted in included publications. There are several dimensions discussed below, and there is a considerable amount of overlap between them. This overlap and its implications for PE practice and policy are discussed in the discussion section. Table 7 shows excerpts about tokenism from included publications that was used to derive syntheses of the dimensions.

Table 7.

Excerpts on Tokenism From Included Publications.

| Author, year | Excerpts about/with tokenism |

|---|---|

| Bess 2009 (18) |

|

| Buckley (2004) (19) |

|

| Dewar (2005) (20) |

|

| Farrington (2016) (21) |

|

| Glauser (2016) (22) |

|

| Hahn (2017) (10) |

|

| Hiebert (2018) (23) |

|

| Majid (2018) (12) |

|

| McCutcheon (2014) (24) |

|

| Nestor (2008) (25) |

|

| Ocloo (2016) (26) |

|

| Pharmletter (2019) (27) |

|

| Robins (2014) (28) |

|

| Supple (2015) (29) |

|

Unequal power

One publication proposed that although tokenism and powerlessness are not synonymous, individuals in tokenistic situations hold unequal power compared to their collaborators, particularly health care professionals (18). In another publication, tokenism was equated to a situation whereby health service decision-making was primarily beholden to health care professionals (24), making patients “invisible” in health care activities (23). This dimension arose when the idea of partnering with patients to improve the quality of care was not internalized by health care professionals (12), which may have encouraged negative attitudes that further limited the extent to which patients can engage meaningfully in health care activities (25). One publication suggested that health care professionals can avoid tokenism by letting go of their traditional habits of mind of what should and should not be in the health care system (12). The idea of power was closely related to capacity to contribute to effective and sustainable change; patients must have the decision-making capacity to catalyze change (10).

According to one publication, PE was used to maintain existing plans and decisions, rather than enable novel ideas and insights from patients and family to transform health services (21). This idea was especially pertinent in situations when health care professionals took the responsibility of speaking on behalf of patients and family, instead of creating the opportunity and space to speak for themselves (28). Tokenism in this form was also motivated by a struggle to maintain existing power structures because health care professionals were more accustomed to utilizing their traditional habits of mind with regard to health service decision-making (12). Similarly, tokenism was described as a “bureaucratic requirement,” emphasizing the challenging dynamics between patients who want to contribute to meaningful change, and powerful, recalcitrant institutions (25).

Limited impact

Four publications stated that tokenism arises when patient input is obtained but not utilized to make a meaningful difference (22,24,26,27). This dimension was conceptualized as “token check mark” (22), “lip-service” (27), and “token patronizing credit” (27). The idea that tokenism limited the impact of patient input was associated with the need to engage patients early and in all health care activities (22,24). When decisions on who, when, and how to involve are left to health care professionals, then patients were seldom involved throughout health care activities, and accordingly, tokenism was more prevalent (24). Two publications suggested that failure in designing adequate supports, resources, and provisions for meaningful PE confers tokenism and also limited the extent to which the beneficial outcomes associated with PE will be observed by health service organizations (12,24).

Ulterior motives

Two publications stated that one of the sources of tokenism is when health care professionals and decision makers used patient experiences, perspectives, and preferences as a way to achieve their personal or professional objectives (23,27). In one content analysis of policy documents, tokenism existed when the perspectives and experiences of patients were modified or removed in an effort to tailor important lobbying messages to decision makers (23). In this case, health care professionals used a subset of patient perspectives that fit within a particular narrative that they believed to be most relevant to the issue at hand, and other information was deemed irrelevant to the context. Another publication discussed how involving a restricted subset of individuals in health care activities that is not representative of the population demographics is a way for tokenism to seep into relationships (26).

Opposite of meaningful PE

Multiple publications used meaningful PE as a concept to elaborate on what tokenism is not (12,19,20,22,24 –29). For example: “…this has amounted to tokenism as opposed to genuine attempt to seek involvement” (19); “…ranging from limited participation or degrees of tokenism, to a state of collaborative partnership in which citizens share leadership or control decisions” (26); “Here are ten proven ways to engage patients in a tokenistic (and not meaningful) way” (28).

Discussion

This review examined how the peer-reviewed and gray literature conceptualized tokenism in PE. Fourteen publications were analyzed to delineate a preliminary set of dimensions for tokenism. Similar to Arnstein’s seminal definition of tokenism, this review found that unequal power represented the majority of relationships characterized as tokenistic. Unequal power manifested in relationships where patients were invited to participate to reaffirm the decisions and plans already in place, rather than enable patient insights to transform health service planning and delivery. Related to this notion was the idea that tokenistic relationships prevented patient input from contributing to meaningful and sustainable change. This finding was especially prevalent when health care professionals used PE to achieve their personal or professional objectives that were not necessarily grounded in patient preferences and perspectives. Finally, this review illustrated how the definitions of tokenism were often juxtaposed with the conceptualizations of meaningful PE. The following sections discuss the broader implications of these findings for PE practice.

Juxtaposition Between Meaningful and Tokenistic Patient Engagement

Included publications regularly juxtaposed tokenism with meaningful PE to highlight the nuances of tokenistic PE. A recently published review delineated 6 concepts that depict meaningful PE: collaboration, cooperation, coproduction, active involvement, partnership, and consumer and peer leadership (7). This review offered important insight for the different ways to conceptualize meaningful PE. For example, while partnership may represent equal power and accountability between patients and health care professionals, leadership may exemplify an orientation toward PE, whereby patients function as decision makers (7). These 2 terms are distinct from tokenism because they represent transforming relationships to favor patients by increasing their decision-making capacity. If tokenism, partnership, and leadership were on a spectrum of decision-making capacity, tokenism would represent unequal power in favor of health care professionals, partnership would represent equal power, and leadership would represent unequal power in favor of patients. All 3 represent some form of engagement, but they are distinguished by the distribution of power between patients and health care professionals.

The International Association of Public Participation Spectrum conceptualizes 5 levels of engagement: inform (provide the public with balanced and objective information to assist them in understanding the problem), consult (obtain public feedback on analysis, alternatives, and decisions), involve (work directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered), collaborate (partner with the public in each aspect of the decision including the development of alternatives and the identification of the preferred solution), and partner (place final decision-making in the hands of the public) (31). Based on this conceptualization, tokenism as defined in this concept analysis is similar to inform, consult, and involve levels. On the other hand, meaningful PE may represent collaborate and partner levels. This spectrum may aid PE practitioners to differentiate the distinctions between the dimensions of tokenism and meaningful PE in an effort to clarify their implications for PE practice. These distinctions also broaden how practitioners understand the impact of tokenism on PE relationships; patients may appear to engage in health care activities, but their involvement, feedback, and input is not perceived as meaningful or relevant to the health care activity by professionals. Juxtaposing tokenism with conceptualizations of meaningful PE encourages practitioners to identify, appraise, and mitigate opportunities for tokenism to seep into patient–health care professional relationships.

Gradations of Tokenism

The findings of this review suggest that there are different gradations of tokenism. On the one hand, all gradations may reflect unequal power distribution that favor health care professionals; this unequal power distribution, on the other hand, may manifest in 2 ways: (1) patients’ input is not integrated or internalized to make meaningful change (limited impact), or (2) patients’ input leads to change that is primarily intended to achieve the personal and professional goals of health care professionals (ulterior motives). The corollary is that a particular gradation may be appropriate for patients and health care professionals under different circumstances because of patients’ diverse engagement preferences. For example, in health care activities that require complex, high-level strategic planning, patients may not have the supports, resources, and knowledge to contribute meaningfully to health care activities (32). As such, some patients, depending on their commitment preferences and personal or professional priorities, may agree to a more “tokenistic” role, whereas other patients may assert the need for support, resources, and knowledge for any sort of engagement to occur.

Due to diverse engagement preferences, tokenism may not be perceived as inherently negative in all circumstances. In PE activities, patients and health care professionals are required to form collaborative relationships, and each group brings essential knowledge, resources, and expertise to the activity. Each group also has a set of preferences and motivations for engagement. In a political and highly professionalized industry, it is extremely challenging for patients to solely contribute to change; they often have to rely on health care professionals to serve as conduits. By nature, the relationships between patients and health care professionals reflect an unequal power distribution whereby the change sought by patients must go through health care professionals. For these reasons, there may always be an element of tokenism in patient–professional relationships. However, tokenism may be inappropriate when PE does not lead to any change or leads to change that goes against what patients intended or desired.

Similar to how tokenism may not be appraised as negative in all circumstances, meaningful PE may not be the ultimate goal for every health care activity. The important caveat is that these decisions about the levels of engagement should match the health care activity context and patients’ engagement preferences, which must be determined through dialogue with patients. Although patients’ intentions and expectations from PE may evolve through the life cycle of an initiative, change becomes more likely when there are appropriate provisions in place for a dialogue that allows the engagement initiative to evolve with engagement preferences.

Relationship Between Patient Engagement and Capacity for Change

One of the most common motivations that patients cite for engaging in health care activities is that their experiences with health services have the potential to contribute to meaningful and sustainable change (33). However, this objective is obfuscated when patients do not have access to the supports, opportunities, and resources that enable them to contribute to change they desire. In such cases, there is still engagement in its rudimentary conceptualization, but it is disconnected from the original intentions and motivations that prompted it. This disconnect may increase dissonance in patients’ original motivations to engage. This disconnect may also adversely affect patients’ motivations to engage in future activities (34) and cause distrust in health care professionals of patients and their motivations (4, 35), which may ultimately affect health care outcomes (36). The findings of this review shed light on the dimensions of tokenism that may allow for a disconnection between the intentions and practice of engagement to seep into PE relationships. The dimensions of tokenism discussed in this review add nuance to patients’ desire to make meaningful contributions to health care activities, while their decision-making capacity is circumscribed by the characteristics of the engagement context.

Limitations of This Research and Future Directions

There is limited literature that discusses tokenism as a primary objective or finding. This review found multiple publications, but few peer-reviewed, empirical research studies have been published. For example, there was only 1 article that discussed tokenism in clinical care. This finding is surprising because there is a long history of unequal power relations between patients and health care providers in health care decision-making. As such, there is an opportunity to conduct rigorous, primary investigations about how patients and health care professionals experience and enable tokenism to influence PE relationships. This objective is vital, as health service organizations continue to involve patients in a wide array of activities, and there is a need to clarify the meaning of terms and concepts that depict engagement to ensure that miscommunication and misrepresentation about the roles, expectations, and goals of engagement are prevented.

The majority of included publications did not identify a particular definition they used to conceptualize tokenism. Future research should work toward explicating definitions of tokenism and its implications for the research context. The findings of this review have shown that tokenism can manifest in a variety of ways, and future research should clarify which dimensions are most appropriate for a specific objective. There also seems to be limited discussion about how the lack of resources, supports, and infrastructure may contribute to tokenistic relationships. There is a need to conduct investigations that clarify the relationships between infrastructure and the dynamics of relationships between patients and health care professionals.

Conclusion

The worst-case scenario is not tokenism but nonparticipation and powerlessness. Tokenism represents a type of decision-making capacity albeit one that reflects unequal power relationships. Patients’ scope of engagement is broadening with time because there is increasing support for PE in health care activities in jurisdictions worldwide. However, there is a need to improve both our understanding and practice of engagement, including the language we use. This concept analysis discussed a set of preliminary dimensions for tokenism that may support PE practitioners to better reflect on how tokenism can seep into relationships, even with authentic intentions, discussions, and motivations, in an effort to prompt the development of strategies to support authentic, meaningful patient–professional relationships.

Author Biography

Umair Majid is a PhD student in Health Services Management and Organization at the University of Toronto looking at improving organizational capacity for patient engagement. He is also a consultant for health service organizations in low- and middle-income countries.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Umair Majid  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4581-7714

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4581-7714

References

- 1. Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boutin M, Dewulf L, Hoos A, Geissler J, Todaro V, Schneider RF, et al. Culture and process change as a priority for patient engagement in medicines development. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maguire K, Britten N. “How can anybody be representative for those kind of people?” Forms of patient representation in health research, and why it is always contestable. Soc Sci Med. 2017;183:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McInerney P, Cooke R. Patients’ involvement in improvement initiatives: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13:232–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forsythe LP, Szydlowski V, Murad MH, Ip S, Wang Z, Elraiyah TA, et al. A systematic review of approaches for engaging patients for research on rare diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:788–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Majid U, Gagliardi A. Clarifying the degrees, modes, and muddles of “meaningful” patient engagement in health services planning and designing. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:1581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann. 1969;35:216–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4:133–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hahn DL, Hoffmann AE, Felzien M, LeMaster JW, Xu J, Fagnan LJ. Tokenism in patient engagement. Fam Pract. 2016;34:290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Solbjør M, Steinsbekk A. User involvement in hospital wards: professionals negotiating user knowledge. A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Majid U. What have we done? The piths and perils of tokenistic engagement in healthcare. Longwoods. 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2019, from: https://www.longwoods.com/content/25582.

- 13. Weber RP. Basic Content Analysis. Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cavanagh S. Content analysis: concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Res. 1997;4:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McTavish DG, Pirro EB. Contextual content analysis. Qual Quant. 1990;24:245–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Majid U. Healthcare in an era of patient engagement: language for ongoing dialogue. Health Sci Inq. 2019;1:54–56. Retrieved from: https://www.healthscienceinquiry.com/2019 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bess KD, Prilleltensky I, Perkins DD, Collins LV. Participatory organizational change in community-based health and human services: from tokenism to political engagement. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:134–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buckley J, Hutson T. User involvement in care: avoiding tokenism and achieving partnership. Prof Nurse (London, England). 2004;19:499–501. Retrieved May 5, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dewar BJ. Beyond tokenistic involvement of older people in research—a framework for future development and understanding. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farrington CJ. Co-designing healthcare systems: between transformation and tokenism. J R Soc Med. 2016;109:368–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glauser W, Stasiuk M, Bournes D. Beyond tokenism: how hospitals are getting more out of patient engagement. Health Debate. 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2019, from: https://healthydebate.ca/2016/02/topic/hospitals-patient-engagement

- 23. Hiebert B, Regan S, Leipert B. Tokenism and mending fences: how rural male farmers and their health needs are discussed in health policy and planning documents. Healthc Policy. 2018;13:50–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCutcheon K, Gormley K. Service-user involvement in nurse education: partnership or tokenism? Br J Nurs. 2014;23:1196–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nestor P, Galletly C. The employment of consumers in mental health services: politically correct tokenism or genuinely useful? Australas Psychiatry. 2008;16:344–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:626–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pharmletter. Parexel’s Alberto Girgnolo on patient engagement: form tokenism to telling contributions. Retrieved July 25, 2016, from: https://www.thepharmaletter.com/article/patient-engagement-from-tokenism-to-telling-contributions-which-pharma-values

- 28. Robins S. 10 ways patient engagement in Canada smacks of tokenism. Retrieved October 15, 2015, from: https://suerobins.com/2014/10/15/10-ways-patient-engagement-in-canada-smacks-of-tokenism/

- 29. Supple D, Roberts A, Hudson V, Masefield S, Fitch N, Rahmen M, et al. From tokenism to meaningful engagement: best practices in patient involvement in an EU project. Res Invol Engage. 2015;1:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. International Association for Public Participation. IAP2’s Public Participation Spectrum. Retrieved October 5, 2018, from: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/foundations_course/IAP2_P2_Spectrum_FINAL.pdf

- 32. Burns KK, Bellows M, Eigenseher C, Gallivan J. ‘Practical’ resources to support patient and family engagement in healthcare decisions: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ, Grit KJ. Patient participation in collective healthcare decision making: the Dutch model. Health Expect. 2010;13:73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Carter A, Greene S, Nicholson V, O’Brien N, Sanchez M, De Pokomandy A, et al. Breaking the glass ceiling: increasing the meaningful involvement of women living with HIV/AIDS (MIWA) in the design and delivery of HIV/AIDS services. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36:936–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. 2014;7:387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meterko M, Wright S, Lin H, Lowy E, Cleary PD. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the influences of patient-centered care and evidence-based medicine. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]