Abstract

Patient and family communication is a well-known factor associated with improved patient outcomes. During the COVID-19 pandemic, visitation restrictions meant communication with patients and their families became a challenge, particularly with intubated patients in the intensive care unit. As the hospital filled with COVID-19 patients, medical students and physicians at Albany Medical Center identified the urgent need for a better communication method with families. In response, the COVID-19 Compassion Coalition (CCC) was formed. The CCC’s goal was to decrease the distress felt by families unable to visit their hospitalized loved ones. They developed a streamlined process for videoconferencing between patients on COVID-19 units and their families by using tablets. Having medical students take responsibility for this process allowed nurses and physicians to focus on patient care. Incorporating videoconferencing technology can allow physicians and nurses to better connect with families, especially during unprecedented times like a pandemic.

Keywords: technology, compassionate care, medical education, COVID-19

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world. In addition to the collective fear of contracting the disease, many across the globe are experiencing isolation. Strict visitor restrictions have made this fear a reality for hospitalized COVID-19 patients fighting their condition alone while worried family members remain home. Family members benefit from seeing clinical improvement, or conversely, the extent of the patient’s suffering in order to make knowledgeable shared decisions about care—especially at end of life (1). Since critically ill patients and their families often have anxiety and depression, clinicians worry that the added restrictions on visitors as a consequence of COVID-19 could magnify this stress (2). Needless to say, family involvement, especially in critical care, is invaluable. It improves communication and increases care satisfaction among the nursing staff, who bear a significant burden of caring for these intensely ill patients (3). Therefore, it has become imperative to find a way to connect family and patients in real time, especially as hospitalized COVID-19 patients face the terrifying possibility of death. The problem is, who can manage the logistics of creating these meaningful connections while resources are stretched thin?

On March 17, 2020, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommended removing medical students from all clinical rotations (4). For most students, suddenly being removed from the frontlines, during the most significant health event in 100 years, was unsettling. A week later, the surge of COVID patients in New York City led to the transfer of hospitalized patients to Albany Medical Center; the urgency of improved communication between patients and family members intensified. Through this necessity was born a self-made team of medical students and frontline physicians who formed the COVID-19 Compassion Coalition (CCC).

Description

The primary goal of the CCC was to decrease the emotional distress felt by families unable to visit their hospitalized loved ones. The team quickly developed a plan to improve communication while still adhering to standardized guidelines to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Objectives were to:

Develop a simple process for videoconferencing on COVID-19 units.

Enhance knowledge of the patient using a “Meet my Loved One” worksheet.

Expedite medication reconciliation.

Quickly connect language translators.

The medical students were uniquely poised to carry out these objectives given their understanding of clinical needs and ability to navigate their hospital. Additionally, students had the time to speak with family members at length, whether it was to help them through the process of establishing the video calls or to be a source of emotional support. This allowed overwhelmed nurses and doctors to remain focused on patient care since the medical students took responsibility at every step of this process. Given the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), a key challenge became implementing the projects without putting students in direct contact with patients, keeping in alignment with the AAMC recommendations.

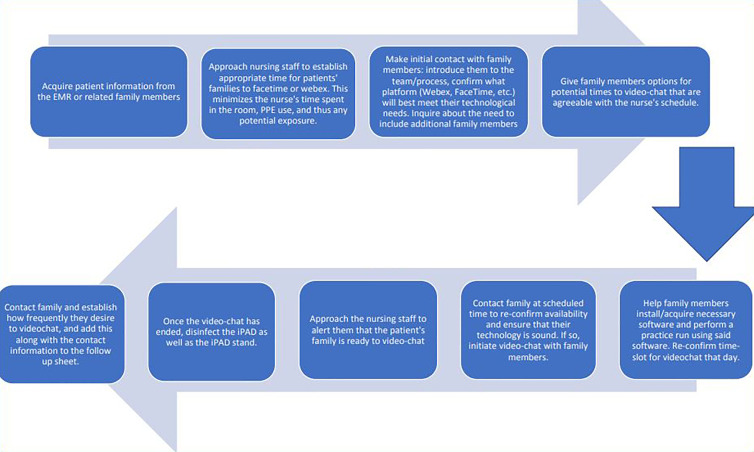

The hospital had previously secured iPad® tablets for another project. Students asked the Information Services department to download 2 programs, Cisco Webex and Apple FaceTime, which were used to initiate video calls between patients and families. For the initial video call, a student instructed the family on how to download the applications and establish the video connection. Many family members were unfamiliar with the technology. In response, the students created a “Webex tutorial,” which was emailed to families that required detailed instructions. Once they established the call, the students placed the iPad® in a sealed plastic bag, attached it to a stand, and gave it to a nurse who rolled it into the patient room. Ideally, this was timed with existing patient care (e.g,, medication administration) to minimize PPE use. The nurses often shared updates on patient care and in some cases, even demonstrated medical interventions, which allowed family members to feel they were part of the process. If their loved one was intubated, family members used the time to sing or sometimes just cry with the patient. Since the iPads were on stands, nurses were free to continue with patient care or leave the room while the call continued. When the call was completed, the nurse then performed their usual PPE doffing process before disposing of the clear plastic bag and returning the iPad® to the student (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Workflow of the COVID-19 Compassion Coalition (CCC).

The CCC implemented additional programs to augment comprehensive, compassionate care. Students asked the family to answer questions about their loved one’s interests and displayed the answers outside the patient’s intensive care unit (ICU) room. The students also created a list of multilingual medical students who could be enlisted to help in emergent situations if there were barriers to quickly obtaining formal language interpretation.

Results

The CCC has provided services to multiple COVID units at our hospital. We believe the initiative eases the burden on health care workers, improves communication with families of patients with COVID-19, and allows for more compassionate, patient-centered care. The ability for a family to have a virtual “face-to-face” encounter with their loved one, even if they are intubated and unable to communicate directly, helps heal both the patient and the family. This has also given family members an essential glimpse into the patient’s status and supplements the updates they get daily from doctors and nurses. By timing many of the calls closely with difficult discussions about prognosis and end-of-life care, family members have a visual aide to help direct decisions about de-escalating care. On multiple occasions, after seeing the patient “face-to-face,” family members who had initially expressed guilt about “giving up” on their loved ones, were able to better understand the arduous journey that the patient had endured and would ultimately make difficult decisions with peace.

In addition to its positive effect on family members, the CCC’s video calling initiative appears to be beneficial to patients themselves. On several occasions, caretakers attributed improvements in their patient’s emotional state with the virtual time spent with loved ones. One nurse in the ICU noted that, while on a call with family, her patient became much more engaged, energetic, and interactive with staff. For patients, families, and health care workers alike, the program provides a necessary lift from the at-times bleak setting of the ICU. One nurse described herself as “tearing up” after the intubated man she was caring for began to open his eyes upon hearing his family members’ voices on the iPad®. Sentiments of gratitude from grieving families are shared daily. Following an emotional conversation with their brother just before he died, the sisters of an ICU patient sent a message of thanks to the CCC:

“It means so much to all of us to be able to tell him we love him as he is in this situation and no one can be there with him. Once again, pass our sincere thanks on to the nurse and his docs from [patient’s] family. You are a rock star, and so are they.”

Lessons Learned

Successful implementation of the video calls required proper communication with the exceptionally busy nursing staff. It quickly became apparent that the initially unstructured guidelines on availability for video calls could be stressful for staff. Therefore, we asked nurses to identify more convenient time slots and alerted families to the need for flexibility in scheduling video calls based on nursing availability. Setting clear expectations between medical students, nurses, and family members helped alleviate these stressors. The nurses reported additional pressure to answer medical update questions, which were more appropriate for the physician. Clarification on the goal of the call before the “appointment” helped; family members were reassured that medical concerns would be addressed by the physician directly at another time. Additionally, methods to ensure efficient PPE usage and manpower were developed as time went on.

Conclusions

The CCC plans to grow alongside the evolving COVID pandemic in Albany. In order to serve as many patients and their loved ones as possible, it became critical that we create a sustainable program that would last beyond the return of students to their clinical duties. The volunteers adapted their process into a service-learning project for preclinical medical students to take over as third and fourth-year medical students go back to clinical rotations.

More than a dozen publications have been produced since April 2020 which address communication with patient families during COVID-19. These generally focus on end-of-life conversations and eschew mention of the day-to-day interactions which we found to be so powerful (5,6). Likewise, several other papers have cited medical student involvement within the community and hospital operations (7,8). However, at the time of publication, this appears to be the first published instance of a medical student initiative which uses technology to connect patients and their families for meaningful, consistent, interactions.

We hope that this student-driven approach at Albany Medical Center can serve as a model for other academic medical centers. This multidisciplinary approach provides a valuable experience for students to volunteer in a way that has real patient impact, while still aligning with the standards set forth by the AAMC.

Author Biographies

Deepika Suresh is a 4th year medical student at Albany Medical College. She is pursuing a career in Internal Medicine and her academic interests include medical education and critical care medicine.

Kevin Flatley is a 4th year medical student at Albany Medical College. He is pursuing a career in Obstetrics and Gynecology and his academic interests include harm reduction for people who use drugs, LGBTQ+ health, and gynecologic surgery.

Margaret McDonough is an Albany Medical College graduate and current Family Medicine resident at Mountain Area Health Education Center in North Carolina.

Nicholas Cochran-Caggiano is a 4th year medical student at Albany Medical College and is applying for residency in Emergency Medicine. His academic interests include public health and health policy as well as resuscitation of critically ill patients.

Peter Inglis is a 4th year medical student at Albany Medical College. His academic interests include interventional radiology and biodesign.

Samuel Fordyce is a 4th year medical student at Albany Medical College. His academic interests include interventional radiology and the interconnection of medicine with technological advancement.

Allison Schachter is a 4th year medical student at Albany Medical College. She is pursuing a career in Obstetrics and Gynecology and her academic interests include gynecologic oncology, gynecologic surgery, and studying global health systems.

Ernesto Acosta is a 4th year medical student at Albany Medical College. He is pursuing a career in Orthopedic Surgery and his academic interests include Orthopedic Oncology, hip fractures, and improving access to care for the underserved.

Danielle Wales is an assistant professor of Medicine/Pediatrics at Albany Medical Center. She is also a clinical assistant professor at the University at Albany School of Public Health and academic primary care physician, with special interest in immunizations, quality improvement, and preventive medicine.

Jackcy Jacob is a medicine and pediatrics trained physician and an assistant professor of medicine at Albany Medical Center. Dr Jacob's interests are in the areas of medical student education and faculty development.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: IRB approval was waived and patient consent was not required for this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Deepika Suresh, BS  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0871-9963

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0871-9963

Ernesto Acosta, BS  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6286-4320

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6286-4320

References

- 1. Hinkle LJ, Bosslet GT, Torke AM. Factors associated with family satisfaction with end-of-life care in the ICU: a systematic review. Chest. 2015;147:82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Griffiths J, Harrison DA, Watkinson P. Anxiety, depression and post traumatic stress disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allen SR, Pascual J, Martin N, Reilly P, Luckianow G, Datner E, et al. A novel method of optimizing patient- and family-centered care in the ICU. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Important Guidance for Medical Students on Clinical Rotations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 17, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2020 https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/important-guidance-medical-students-clinical-rotations-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak.

- 5. Hart J, Turnbull A, Oppenheim I, Courtright K. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 Era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e93–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Voo TC, Sengttuvan M, Tam CC. Family presence for patients and separated relatives during COVID-19: physical, virtual, and surrogate. J Bioeth Inq. 2020:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quadri NS, Thielen BK, Erayil SE, Gulleen EA, Krohn K. Deploying medical students to combat misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20:762–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soled D, Goel S, Barry D, Erfani P, Joseph N, Kochis M, et al. Medical student mobilization during a crisis: lessons from a COVID-19 medical student response team. Acad Med. 2020;95:1384–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]