Abstract

Background:

Empathy is critical for optimal patient experience with health-care providers. Verbal empathy is routinely taught to medical students, but nonverbal empathy, including touch, less so. Our objective was to determine whether instruction encouraging empathic touch and eye gaze at exit can impact behaviors and change patient-perceived empathy.

Materials:

A randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial of 34 first-year medical students was conducted during standardized patient (SP) interviews. A video either encouraging empathic touch and eye gaze at exit or demonstrating proper hand hygiene (control) was shown. Encounter videos were analyzed for touch and eye gaze at exit. The Jefferson Scale of Patient Perceptions of Physician Empathy was used to measure correlations. Intervention students were surveyed regarding patient touch.

Results:

Of this, 23.5% of intervention students touched the SP versus zero controls; 88.2% of intervention students demonstrated eye gaze at exit. Eye gaze at exit positively impacted patient-perceived empathy (correlation = 0.48, P > .001). Survey responses revealed specific barriers to touch.

Conclusion:

Medical students may increase perceived empathy using eye gaze at exit. Instruction on empathic touch and sustained eye gaze at exit at the medical school level may be useful in promoting empathic nonverbal communication. Medical educators should consider providing specific instructions on how to appropriately touch patients during history-taking. This is one of the few studies to explore touch with patients and the first ever to report the positive correlation of a health provider’s sustained eye gaze at exit with the patient’s perceived empathy. Further studies are needed to explore barriers to empathic touch.

Keywords: empathic touch, eye gaze, empathy, standardized patient encounter, patient perception

Introduction

Many clinical encounters are said to be devoid of meaningful personal interaction, creating challenges for an empathic relationship with patients (1,2). The importance of empathy in the patient–physician relationship has been well established (3,4). An empathic approach to patient care results in better health outcomes and greater patient satisfaction (5,6). Much debate has centered on how to nurture empathy among medical students (7). Studies have shown that training medical students in empathy is indeed possible (8,9). One recent study examined the results of an intervention with the proper use of EMR records to improve empathy of medical students and found that it improved medical students’ empathic communication with standardized patients (SPs) (10).

Importantly, empathy is conveyed through verbal and nonverbal expression (11). Research shows that patients are not always direct, but instead provide “clues” to their concerns (12). Good nonverbal communication is critical to proper patient-centered medical care (13). Yet, while historically medical education has placed a great deal of attention on verbal communication with patients to demonstrate empathy, relatively little focus has been placed on nonverbal empathic communication (14). In teaching medical students who will practice in ever-increasingly diverse multicultural communities, the importance of nonverbal expressions of empathy may carry greater importance (14). It is the recognition of this need among health-care providers, particularly due to increasingly diverse patient populations, that led a group of physicians at Massachusetts General Hospital in 2014 to develop and test a teaching tool for nonverbal empathic behaviors to other physicians (14).

The feasibility of promoting nonverbal communication behaviors to improve empathy at the medical student level has not been previously explored. We therefore studied the effect of physical touch and eye gaze at exit on SP’s perceived empathy as well as the impact of a brief instructional video, encouraging students to touch patients.

Methods

Study Setting

Randomized controlled trial of 34 first-year students at the Northeast Ohio Medical University (NEOMED) College of Medicine in the Foundations of Clinical Medicine (Clinical Skills) course. The research was conducted during a mandatory first-year medical student interview with SPs. For this interview, there were 2 SP cases used. Demographics for each case were a 44-year-old female and a 65-year-old male/female. Sixteen SPs were recruited for these cases, which included 7 females and 9 males.

Study Design

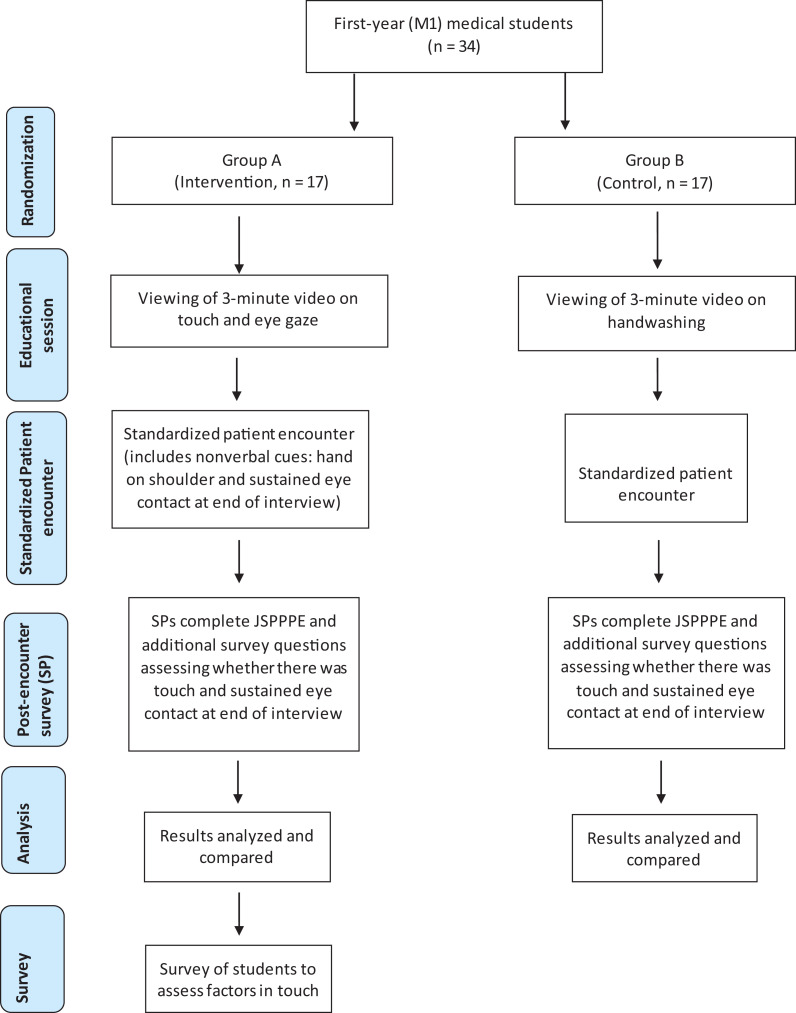

A total of 34 first-year medical students were randomized into 2 groups (Figure 1). Students in the intervention group (8 females, 9 male) viewed a 3-minute instructional video regarding touch and eye gaze at exit in the patient encounter, while the control group (11 females, 6 males) viewed a 3-minute handwashing video. Both groups then interviewed SPs for 20 minutes.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of research study protocol.

Data Collection

The Jefferson Scale of Patient Perceptions of Physician Empathy (JSPPPE) is a validated and widely used instrument to measure patient-perceived empathy (15,16). A 7-item questionnaire uses ratings from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). We added 5 additional items to assess whether specific nonverbal behaviors were performed by the student. A sample additional item was “Did the Student Doctor make eye contact with you on his or her way out the door after the encounter?”

Audiovisual recordings of SP encounters were analyzed for touch (excluding routine handshake), eye gaze at exit, and handwashing. A true “empathic touch” was defined as a physical interaction by the student, associated with an empathic moment with the SP. Any “pseudo-touches” (reaching out to the SP in reaction to information relayed) were noted but not counted. Any sustained eye contact with the SP at exit was also noted. A brief survey was given to students regarding their experiences with physical touching of SPs to identify barriers to such touch.

Statistical Analysis

Correlations between SP perceived empathy with physical touch and eye gaze were assessed using the JSPPPE (3,4). Levene’s test of median-based homogeneity of variance assessed data distribution, and the Mann-Whitney U test compared differences between groups. Kendall’s rank correlation indicated correlations among JSPPPE responses.

Results

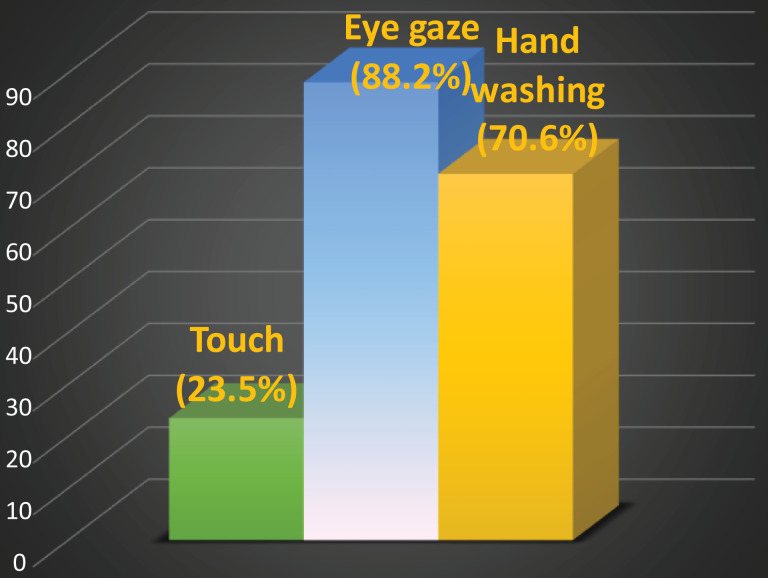

Results indicated that 23.5% (4/17) of the touch video (intervention) group performed at least one touch during the SP encounter, whereas 0% (0/17) controls. Eighty-eight percent (15/17) of intervention students demonstrated eye gaze at exit, versus 29.4% (5/17) controls. Analysis with JSPPPE scores compared all 20 students who performed eye gaze at exit versus those who did not. A total of 70.6% of students (12/17) who viewed the “hand hygiene” video were compliant with hand hygiene. Hand hygiene compliance was greater than touch (Figure 2). Eye gaze at exit was the only maneuver that showed a statistical correlation with JSPPPE scores. Kendall’s Tau (correlation) was 0.479 for eye contact at exit with a 2-tailed significance of .001.

Figure 2.

Student compliance with video instruction (touch, eye gaze, hand hygiene).

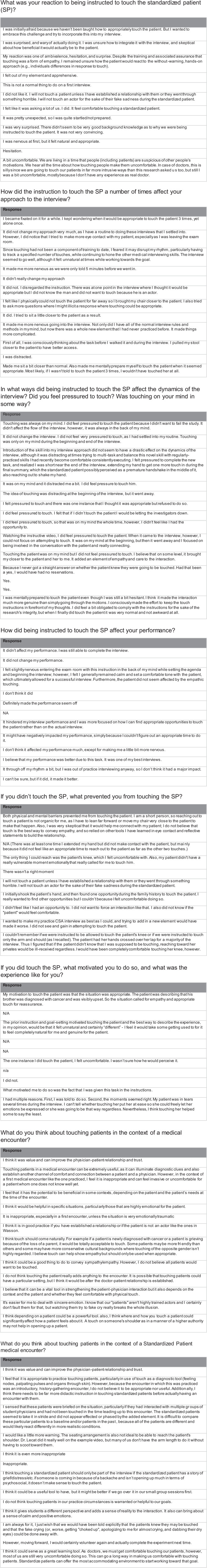

In the survey that followed the study protocol, some students reported discomfort and uncertainty related to physical touch with a patient during the interview (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Student responses to survey regarding touching standardized patients (SPs).

Discussion

Medical education has traditionally focused on improving verbal empathy. However, the need for portraying empathy in nonverbal communication skills during patient–physician encounters is increasing. Our study demonstrates one approach, through educational video, in which nonverbal techniques in the patient encounter can successfully be promoted in teaching medical students. Perhaps the most interesting facet in recent studies on nonverbal behaviors is what they reveal about the patient’s perception of the health-care provider. For instance, while intuitively empathic nonverbal maneuvers have been long thought to convey warmth, Kraft-Todd et al (17) recently showed that nonverbal behaviors project both warmth and technical competence in the eyes of the patient. This has important implications for establishing patient satisfaction, which has been linked to interpersonal trust between patients and their health-care providers (18).

Physical touch serves as one key tool of empathic, nonverbal communication. In general, 2 forms of touch have been described in the physician–patient encounter: diagnostic touch with a clinical aim that serves to help arrive at a diagnosis and healing touch that has social significance or meaning (ie, hug, handshake, or pat on back) (19,20). It has been suggested that the act of touching results in several positive benefits for the therapeutic relationship between practitioner and patient (20,21). Thus, healing touch serves as a powerful form of empathic communication, and simple maneuvers such as placing a hand on the shoulder, handshake, or holding of the patient’s hand may go a long way in creating closeness, alleviating anxiety, and establishing a patient’s trust and confidence in the health practitioner (22). Importantly, findings in one study show that patients feel uncomfortable after more than 3 occasions of physical touch during an interview (23).

Yet, the act of empathic touch among medical students and their comfort level is unclear and has not been widely studied. Interestingly, in response to the videos, fewer students in the intervention group (23.5%) touched the SP during the interview, while 88.2% in the same group (vs 29.4% in the control) demonstrated eye gaze upon exit. Seventy percent in the control group washed their hands after watching the control video. Our data suggests it is easier to promote the behaviors of eye gaze upon exit and handwashing, than touching. However, touching of the patient in about one quarter of the intervention students versus zero in controls indicates the potential of teaching and promoting empathic touch.

There are clear challenges in promoting touch in patient/SP interviews. Reported barriers to touch include fear of touching the patient due to a lack of knowledge in how to touch the patient. Students expressed discomfort in touching SPs, particularly given current notions about the inappropriateness of touching others in public. Providing specific instructions on how to carry out an empathic touch may be warranted. Our results indicate the need to make students more comfortable touching SPs during an interview.

It must be remembered that these were first-year medical students without much actual patient experience. The responses to the request to touch the patients were varied. Many were surprised and some said they wanted more training in touch. Others thought it was inappropriate to touch a patient, much less a standardized patient under any circumstance on the first visit. Clearly, there were barriers to touch for some, but not for others. Students mentioned the following as barriers to touch: patient unfamiliarity, low degree of emotional distress, and use of SPs as patients. In addition, SPs, being actors, presented a barrier to touch for some. We usually assume SPs to be the highest fidelity example of patient encounter simulation, but this may be an example of a limitation.

Our study is the first to explore the correlation of a health provider’s eye gaze at exit with the patient’s perceived empathy. There was a statistically significant correlation between eye gaze at exit and JSPPPE scores. This finding corroborates the results of previous studies that have demonstrated a relationship between eye-gaze patterns and empathy (24). Montague et al (23) have shown that a physician’s gaze significantly impacts the patient encounter. Yet anecdotally, there are moments in the clinical encounter that are devoid of eye contact by the physician. This is only worsened with a computer in room, competing for the physician’s attention. For instance, a physician may have his or her back turned to the patient without maintaining eye gaze as he or she exits the room at the end of the patient encounter. As the end of the encounter presents one final opportunity to leave an impression in the patient’s mind, the physician’s eye gaze as he or she exits the room may have unique importance.

The strengths of our study include the randomized and double-blinded protocol and a mixed-methods methodology. Studies report mixed results in terms of whether empathy declines in the last year of medical school compared to the first year (9,25,26). Thus, our study included first-year medical students to best measure empathy in a student subset in which empathy may be at its highest level.

The study has several notable limitations, including small sample size. It only enrolled first-year medical students. It is possible that variations in demonstrated empathy may exist in students at later stages of medical school. Additionally, while the intervention group was encouraged to physically touch their patients, not all encounters entailed narratives warranting an “empathic touch.” Encounters in which students touched the SPs may have been in the context of patient histories that were more likely to elicit empathic responses compared to others.

Our study only explored student feedback from the experience of touching SPs and did not delve into SP reactions to touching by the students (apart from the empathy scoring). Thus, we lack qualitative insights on whether the experience of being touched helped in building empathy in the view of the SP.

The nature of SP and medical school interactions, in which both parties are aware of their roles in a situation that is not real, limits our ability to definitely determine whether the same results would apply in real-life medical encounters that routinely occur between physicians and patients. Thus, the findings may be influenced by the perceptions of the students who knew they were partaking in a graded exercise and the SPs who were aware of their role as actors.

It is also important to note that not all patients may welcome nondiagnostic physical touch and sustained eye contact by the physician, as individual comfort levels may differ. Furthermore, perceptions of physical touch and sustained eye gaze may vary across cultural and religious groups. Thus, any implementation of a program in medical schools that teaches nonverbal empathy should ideally mention situations during which empathic touch and eye contact may not be appropriate.

Conclusions

The study illustrates the potential of greater physical touch and eye gaze to improve empathy and interpersonal connection among medical students during their medical school career and beyond. It reveals a significant positive correlation between sustained eye gaze at exit and a patient’s perception of empathy; we believe this is a new finding. The touch video appeared to result in 23.5% of students touching their patients. This demonstrates the potential of brief instructional videos in teaching nonverbal empathy. An opportunity exists to improve student comfort with touching patients and for providing specific guidelines on touch. Resistance to touching SPs as patient may need to be directly addressed in the orientation or prebrief prior to the start of the simulation. Just as we provide learners the opportunity to see, touch, and experience the examination room, bed, instruments, and setting where they will conduct the interview, we may need to educate and normalize professional empathic touch in the context of the medical interview.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to instruct and encourage touch, and eye gaze at exit, using brief videos, and correlate these behaviors with an empathy score. Further studies are needed to explore barriers in empathic touch during medical student–SP interactions. Perhaps the best summary comment is given by a student: “I think it (using SP encounters to teach and encourage empathic touch) could serve as a great learning tool. As doctors, we must get comfortable touching our patients, however, most of us are still very uncomfortable doing so. This can go a long way in making us comfortable with touching patients. Standardized patients can offer the most psychologically safe and accommodating environment to start working toward that goal.”

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance and cooperation of the staff at the William G. Wasson, MD, Center for Training, Assessment and Scholarship at NEOMED.

Author Biographies

Paul Lecat, is professor of Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Family and Community Medicine at NEOMED. He is codirector of the Foundations of Clinical Medicine Course and Clinical Experience Director for the Internal Medicine Clerkship at the NEOMED College of Medicine.

Naveen Dhawan, is a current medical student with a research interest in the physician–patient relationship and empathy in medicine. He previously conducted the first-ever study on physician empathy in correctional health-care settings.

Paul J. Hartung, is professor of Family and Community Medicine at NEOMED.

Holly Gerzina, serves as assistant professor of Family and Community Medicine and the Executive Director of the William G. Wasson, MD, Center for Clinical Skills Training, Assessment and Scholarship and Interprofessional Education Services at NEOMED.

Robert Larson, is manager of Assessment at NEOMED.

Cassandra Konen-Butler, is the associate director of Operations in the William G. Wasson, MD, Center for Clinical Skills Training, Assessment and Scholarship and Interprofessional Education Services and an Adjunct Instructor of Family and Community Medicine at NEOMED.

Authors’ Note: The study was approved by the Northeast Ohio Medical University (NEOMED) College of Medicine institutional review board (IRB) and conducted upon approval. The study was presented at the Cleveland Clinic Patient Experience Empathy and Innovation Conference, June 18-20, 2018; Cleveland, OH.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Naveen Dhawan, MBA  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5431-2195

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5431-2195

References

- 1. Shapiro J. Walking a mile in their patients’ shoes: empathy and othering in medical students’ education. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3:10 doi:10.1186/1747-5341-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Derksen F, Bensing J, Kuiper S, van Meerendonk M, Lagro-Janssen A. Empathy: what does it mean for GPs? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2015;32:94–100. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmu080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1563–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:S9–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27:237–51. doi:10.1177/0163278704267037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94207 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shapiro J. How do physicians teach empathy in the primary care setting? Acad Med. 2002;77:323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Batt-Rawden SA, Chisolm MS, Anton B, Flickinger TE. Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated, systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88:1171–7. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M. Medical students’ understanding of empathy: a phenomenological study. Med Educ. 2012;46:306–16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. LoSasso AA, Lamberton CE, Sammon M, Berg KT, Caruso JW, Cass J, et al. Enhancing student empathetic engagement, history-taking, and communication skills during electronic medical record use in patient care. Acad Med. 2017;92:1022–7. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haase RFTD. Nonverbal components of empathic communication. J Counsel Psychol. 1972;19:417–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277:678–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:315–8. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Riess H, Kraft Todd G. E.M.P.A.T.H.Y.: a tool to enhance nonverbal communication between clinicians and their patients. Acad Med. 2014;89:1108–12. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glaser KM, Markham FW, Adler HM, McManus PR, Hojat M. Relationships between scores on the Jefferson scale of physician empathy, patient perceptions of physician empathy, and humanistic approaches to patient care: a validity study. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:CR291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kane GC, Gotto JL, Mangione S, West S, Hojat M. Jefferson Scale of patient’s perceptions of physician empathy: preliminary psychometric data. Croat Med J. 2007;48:81–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kraft-Todd GT, Reinero DA, Kelley JM, Heberlein AS, Baer L, Riess H. Empathic nonverbal behavior increases ratings of both warmth and competence in a medical context. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177758 doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0177758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hojat M, DeSantis J, Gonnella JS. Patient perceptions of clinician’s empathy: measurement and psychometrics. J Patient Exp. 2017;4:78–83. doi:10.1177/2374373517699273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bruhn JG. The doctor’s touch: tactile communication in the doctor-patient relationship. South Med J. 1978;71:1469–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Montague E, Chen P, Xu J, Chewning B, Barrett B. Nonverbal interpersonal interactions in clinical encounters and patient perceptions of empathy. J Particip Med. 2013;5. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green L. Touch and visualisation to facilitate a therapeutic relationship in an intensive care unit—a personal experience. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1994;10:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davidhizar R. The “how to’s” of touch. Adv Clin Care. 1991;6:14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Montague E, Xu J, Chen PY, Asan O, Barrett BP, Chewning B. Modeling eye gaze patterns in clinician-patient interaction with lag sequential analysis. Hum Factors. 2011;53:502–16. doi:10.1177/0018720811405986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cowan DG, Vanman EJ, Nielsen M. Motivated empathy: the mechanics of the empathic gaze. Cogn Emot. 2014;28:1522–30. doi:10.1080/02699931.2014.890563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pedersen R. Empirical research on empathy in medicine—a critical review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:307–22. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petek Ster M, Selic P. Assessing empathic attitudes in medical students: the re-validation of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy—student version report. Zdr Varst. 2015;54:282–92. doi:10.1515/sjph-2015-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]