Abstract

In the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019, virtual visits have become the primary means of delivering efficient, high-quality, and safe health care while Americans are instructed to stay at home until the rapid transmission of the virus abates. An important variable in the quality of any patient–clinician interaction, including virtual visits, is how adroit the clinician is at forming a relationship. This article offers a review of the research that exists on forming a relationship in a virtual visit and the outcomes of a quality improvement project which resulted in the refinement of a “Communication Tip Sheet” that can be used with virtual visits. It also offers several communication strategies predicated on the R.E.D.E. to Communicate model that can be used when providing care virtually.

Keywords: virtual visits, telehealth, communication, empathy, webside manner

Introduction

The novel coronavirus has dramatically altered the way health care is delivered in this country. Almost overnight, professional societies and health care organizations began urging the use of telehealth practices to provide follow-up care and urgent care including screening for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (1 –4). This viral pandemic prompted the rapid deployment and adoption of telehealth services without permitting clinicians to reflect on transitioning their best communication practices to a virtual setting. One health care organization reported that their provision of telehealth services accelerated exponentially, increasing from an average of 5000 visits a month to 200 000 during the ordered shutdown (4).

Telehealth is defined as the “use of communication technology to provide access to health information, consultation, monitoring, diagnosis, and self-management support ”(5). It was introduced as early as the 1960s, but advancements and societal adoption of technology made virtual visits more accessible, affordable, and efficient over the past 4 decades (6).

Webside Manner and Telecompetence

Sir William Osler, often referred to as “the father of modern medicine,” is credited with modeling the behaviors associated with bedside manner. Osler is revered for his innate ability to offer comfort, listen attentively, tender respect, and provide an empathic response to those seeking healing and reprieve from their suffering (7). “Webside manner” has emerged as the term used to convey the clinician’s ability to transfer these relational skills via technology (8 –10). Telecompetence is the term used to describe the requisite skills and proficiency that clinicians should demonstrate to foster relationships, promote healing, and convey empathy during virtual visits (11). The use of empathic statements is critical to promoting relationship-centered care. Though emotion recognition software is quickly advancing, it remains in its infancy. For now, virtual visits can present communication challenges as the emotional cues that are easily recognized in a traditional visit may go unrecognized (12). The purpose of this article is to discuss the importance of empathy and examine the application of the R.E.D.E. (pronounced ready) Model to virtual visits and introduce a communication tip sheet that can be used when conducting virtual visits (13).

The Present Research

The research literature on clinician use of empathy in virtual visits is limited. While the literature supports the use of telehealth for chronic disease management such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma and nonemergent illnesses including sinusitis, dermatitis, and conjunctivitis, there exists a paucity of research on relationship-centered communication practices in virtual visits (14).

Researchers from Northern Illinois University conducted a literature review of 45 articles that represented an array of disciplines and clinical specialties. While unable to identify clinician behaviors that were generalizable, the authors offered important considerations for practice and education. These include perceptions of the utility of telehealth; differences in communication patterns such as pace and type of discourse, reliance on visual cues by both clinician and patient, most notably in communicating empathy and building rapport; and confidentiality and privacy in health care delivery (15).

Investigators examined patient perceptions of physician empathy at a comprehensive stroke center. Fifty patients were seen via telehealth, and 20 patients were seen via in-person visits. Physician empathy was assessed using the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) questionnaire. Each of the CARE items was rated very good or excellent by 87% of the participants in the telemedicine group. No differences were noted between the telemedicine and in-person visit groups in their perception of physician empathy. The authors included 12 recommendations for best practice telemedicine etiquette, which ranged from orienting the patient to the visit, imaginatively entering the patient’s situation, acknowledging the patient’s worries and concerns to identifying others in the room, and including them in the discussion (16).

A study conducted in British Columbia surveyed 399 patients who participated in a virtual visit. The findings revealed that 93% of the respondents reported their visit was of high quality and 91% stated that their visit was “very” or “somewhat” helpful in resolving the health issue for which they sought care. Seventy-nine percent of the respondents reported that their most recent virtual visit was as thorough as an in-person visit (17).

A comparison between virtual visits and face-to-face visits provided by 5 physicians to 20 patients demonstrated that more time was spent in the virtual visit. No statistical difference was noted in the type of questions posed by the physicians in the virtual visit and face-to-face encounter. However, statements of praise, facilitation, and empathy were observed less in the virtual visits (18).

Nineteen patients requiring consultation for pulmonary illnesses were enrolled in a study evaluating patient–physician communication during a virtual visit. The control group of 8 patients were assigned in-person consultations with a pulmonologist, whereas the intervention group of 8 patients received care virtually. The visits were videotaped and coded for patient–physician verbal and nonverbal statements using the Roter Interaction Analysis System. There were no differences in the number of words verbalized between the virtual visits and in-person encounters. There were equal percentages of physician and patient verbalizations, on average, with in-person visits (46% each); however, physicians accounted for more words than patients in virtual visits (48% vs 38%). Information exchanged focused primarily on medical as opposed to psychosocial content for both visit types. However, a trend was observed showing more psychosocial content in the in-person versus virtual. Physicians were more likely to use orientation statements during in-person encounters; patients made more requests for repetition during virtual visits. No differences in global affect ratings were detected. The authors concluded that virtual visits are more physician-centered, with physicians controlling the dialogue and patients taking a more passive role (19).

In a study exploring the experiences of patients and clinicians participating in a follow-up visit, patients were asked to rate a variety of items that might influence their satisfaction of the visit. In addition to convenience and logistics, the patients were queried about the time spent with the clinician, personal connection they experienced during the virtual visit, and overall assessment of the quality of experience. When rating “the personal connection felt during the visit,” 32.7% reported the office visit is better, 5.5% reported the virtual visit is better, and 59.1% reported no difference (20).

Researchers in Australia were interested in exploring the impact of an embedded empathic agent on their website to increase adherence to recommended therapies for children with incontinence. The website was introduced to children and their families while waiting to be seen in a highly specialized clinic. The empathic agent, known as Dr Evie (evirtual agent for Incontinence and Enuresis), was designed to be a culturally inclusive figure which represented the multicultural society of Australia. Empathic flow sheets were created that captured the dialogue and incorporated personalized treatment advice and included meta-relational communication strategies including greeting and farewell rituals and politeness and inclusion behaviors. The 6-month trial using Dr Evie, as compared to the printed text of treatment strategies, revealed that 74 children with urinary incontinence demonstrated an overall reported improvement in 74% of the participants, with 38% reported a resolution of their incontinence without the need to seek specialist care (21).

The Delphi technique was used by nursing faculty in the Netherlands to determine competencies required for nursing providers of telehealth services. A panel of 51 experts including both nurses and patients were asked to identify essential competencies from a list of 52 items. The panel reached a consensus on 14 different skills with 7 overarching themes: knowledge, attitudes, general skills, clinical skills, technological skills, implementation skills, and communication skills. Empathy was highlighted as an important telehealth communication skill (22).

Follow-up interviews of 27 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, who had participated in one previous telehealth visit, were contacted to ascertain their perspectives about their experience. The patients reported that they were satisfied with the convenience of the virtual visits and ease of access. They identified 4 significant barriers: concern over the accuracy of the physical exam, engagement of the clinician, their apprehension in voicing a concern, and the ability to establish a meaningful relationship. The researchers offered a number of communication strategies generated from the interviews which include the following: develop patient education materials that describe a virtual visit and how to communicate concerns, encourage providers to explore patient preferences and goals, respond empathically to patient concerns, use technology to engage patients with behaviors traditionally used in inpatient visits, and develop a “webside” manner (23).

The R.E.D.E. Model

The R.E.D.E. Model was used as the framework for the creation of the virtual visit tip sheet as it is the relationship-centered communication approach that has been embraced by the clinicians where the quality improvement project was completed. Over 97% of the professional staff attended an 8-hour class, with 5 hours of the course being dedicated to skills practice and feedback. The course is a required component for the onboarding of professional staff, residents, and advanced care providers.

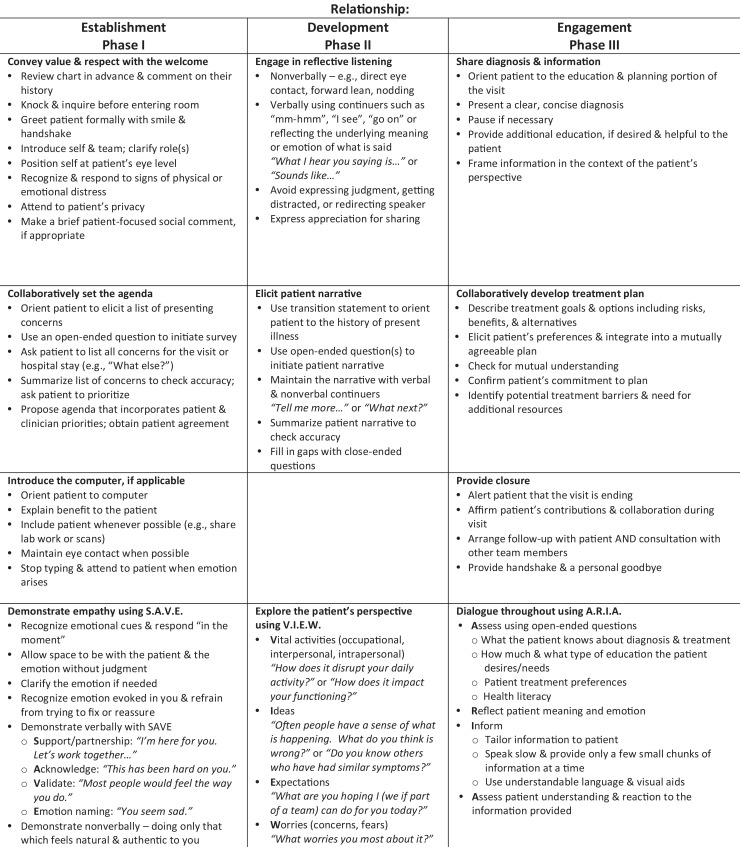

The R.E.D.E. Model “applies effective communication skills to optimize personal connections in three primary phases of a relationship: establishment, development and engagement” (13) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

R.E.D.E. to Communicate® Skills Checklist.

Phase 1: Establishing a Relationship

The first phase of R.E.D.E. is establishing a relationship. This phase addresses 4 overarching skills: conveying value and respect with the welcome, collaboratively setting an agenda, introducing the computer, and demonstrating empathy. The use of empathic statements is critical to fostering relationship-centered care because it humanizes our patients. Through the thoughtful and authentic use of empathy, clinicians can convey an understanding of the patient’s situation, perspective, and feelings and bear witness to his or her suffering. Research has found that empathy declines during medical school and residency and in the initial years of medical practice due to competing demands, time pressures, and a heavy patient load (24). The R.E.D.E. Model has been demonstrated to improve measures of patient satisfaction, reduce physician burnout, and improve physician empathy and self-efficacy and support the ongoing refinement of communication skills training (25).

Phase 2: Developing the Relationship

The second phase of R.E.D.E is developing the relationship. Phase 2 skills concentrate on reflective listening, eliciting the patient narrative of the history of present illness and getting to know the patient as a person. The mnemonic “V.I.E.W.” is used to remind us to explore the patient’s perspectives. This includes learning about the patient’s vital activities (occupational, interpersonal, and intrapersonal) and what has changed as a result of their health care concern. Exploring what ideas the person has about the problem and eliciting expectations as well as worries or fears allows the clinician to not only acknowledge and validate the emotion but also appropriately respond to each concern (13).

Phase 3: Engaging the Relationship

Phase 3 skills focus on sharing the diagnosis and related information in the context of the patient’s perspective, creating the treatment plan together and providing closure to the visit. This phase concentrates on identifying the next steps and envelops the patient in the discussion of treatment options and choices, risks and benefits, and potential obstacles in following the plan of care (13).

Developing Webside Manner

The authors were asked by the Chief Patient Experience Officer at our organization to enhance an existing “Communication Tip Sheet” that would offer recommendations on strategies to be more relationally centered during virtual visits. We were provided with the names of high-volume providers of virtual visits at our organization who were identified by patients as being highly relationship centered in virtual visits by the Office of Clinical Transformation. Eleven clinicians were contacted and invited to participate in a 13-question online survey that would assist the authors in creating the Tip Sheet (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Communicating During a Virtual Visit Survey Questions.

| 1. What techniques do you use to open a virtual visit? |

| 2. How do you reconnect with patients in a virtual visit? |

| 3. What techniques do you use to close a virtual visit? |

| 4. How do you clarify patient emotion? |

| 5. How do you respond to patient emotion? |

| 6. How do you convey empathy verbally? Nonverbally? |

| 7. Are there communication skills that do not seem to translate well to a virtual visit? |

| 8. How much time is allotted for your virtual visits? Is their flexibility in the time? How are patients made aware of the time allotment, if any? |

| 9. How do you organize your virtual visits? |

| 10. What are the selling points of a virtual visit from a clinician perspective? |

| 11. What are the disadvantages of a virtual visit from a clinician perspective? |

| 12. Three words you would associate with a virtual visit? |

| 13. What is your signature strategy in communicating with patients during a virtual visit? |

Six individuals responded to our e-mail invitation and agreed to a follow-up interview, either in person or by phone. Two physicians, 2 registered nurses, a dietitian, and a genetic counselor shared their best relationship promoting practices. The online surveys were reviewed, and follow-up interviews were held with each participant. The follow-up interviews permitted each participant to explain and expand upon their online responses. Responses that addressed the initiation of the virtual visit and strategies they used to employ empathy are presented here (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Communicating During a Virtual Visit Survey Responses (N = 6).

| Question and Response |

|---|

| Q1. What techniques do you use to open a virtual visit? |

| R1. The same I use in the office. Greet the patient with a warm hello and reintroduce myself. |

| R2. Greet the families with a smile. Tell them how nice it is to meet them. |

| R3. Offer a warm and genuine “hello.” |

| R4. Greet warmly! Acknowledge the different setting. I offer a brief tutorial and present trouble shooting recommendations. Then I ask them “What are your concerns that you want to discuss during our visit?” |

| R5. I make sure the patient can hear and see me clearly, otherwise I begin my visit as I would in the office. |

| R6. When I connect to patients and see their face on the screens, I greet them by saying “how nice to see you again” something like that to let them know I am delighted to see their face on the screen. |

| Q3. How do you clarify patient emotion? |

| R1. I respond with “so what I am hearing you say is…” |

| R2. Since my visits involve the entire family, I am diligent to pay attention to all the individuals sitting in front of me. I ask for feedback after I have provided a “chunk” of information. |

| R3. I find virtual visits afford more face-to-face time than office interactions since we are sitting face-to-face and I am not trying to document in their “chart.” |

| R4. Asking targeted, but flexible questions, “You seem upset by that last piece of information. Did it anger you? Sadden you? Surprise you?” |

| R5. I pay close attention to body language. |

| R6. I watch them on the screen. I listen intently to the subtle nuances in their voice. I can connect with people easily. I get a sense of a person’s emotion by watching but REALLY listening…not just to the words but the way in which they vocalize and verbalize their worries, fears, and anxieties. |

| Q4. How do you respond to patient emotion? |

| R1. With empathy. |

| R2. I empathize. I listen to their concerns and validate them. |

| R3. I acknowledge it and do not judge it. |

| R4. Acknowledge and validate their feelings. |

| R5. Same as I would in the office. I change my tone of voice and rate of speed based on the patient’s expression of emotion. |

| R6. I get closer to the screen and I use my voice to slowly and softly express empathy “Oh, I am SO sorry to hear that…” |

| Q5. How do you convey empathy verbally? |

| R1. My “go to phrase” is “I hear you.” I say it very gently. |

| R2. I acknowledge the statement and ask if they would like to tell me about how they are feeling. I only see families once as I provide a VERY SPECIFIC type of virtual visit. |

| R3. I often say the following when there is intense emotion associated with a personal or potentially embarrassing disclosure…“Thank you very much for sharing such a personal concern. Your willingness to tell me this will help me to help you.” |

| R4. I use a pause…I find this allows the patient to tell more of the story if they wish to before I respond slowly with “I am sorry you are going through this. I want you to know I am here for you and wish to help you get through (whatever the situation is).” |

| R5. Empathy statements are integral to my profession and I don’t find that telemedicine significantly impedes my traditional approach. |

| R6. I validate the patient’s emotions. “I would feel frustrated too.” “This kind of thing is never easy.” “That took a lot of courage to share that with me.” |

| Q6. Are there communication skills that don’t seem to translate well to a virtual visit? |

| R1. Physical touch. |

| R2. Besides being able to physically comfort a patient, I don’t think so. |

| R3. Experiencing spontaneity of emotion in the same physical space. |

| R4. Of course, there are, but there is also less distraction. Often, patients are stressed from trying to navigate traffic, finding a parking space, getting to the office, and waiting to see me. With virtual visits I am not encountering frustration or exasperation as I am seeing them when it is convenient for them in their own space. |

| R5. Certainly. Physical touch as well as close eye contact are lacking in virtual visits. |

| R6. I like to hug my patients when I feel their pain is too much. That is the only thing I cannot do. |

| Q11. What is your signature strategy in communicating with patients during a virtual visit? |

| R1. I have created my own template for virtual visits. I have learned to make sure I ask certain questions that most of my postoperative patients raise. Since many of the questions are related to intimacy issues, I make sure I provide the information if the patient does not ask. I am very intentional about how I use my voice. As a nurse, I know that my voice is an instrument in caring. |

| R2. Showing my interest in them, their concerns, and questions. Engaging them in meaningful conversation. Taking my time, being available to them after the visit by providing my contact information for any further issues or questions. I also always ask about how they liked the virtual visit. I tell them their input is very valuable to me. |

| R3. I only see established patients, so I make sure I greet them warmly (encourage presence of family members). I get an update as to how they have been since we last spoke, create a plan together to address their concerns, and provide a summary of what we discussed. |

| R4. Taking a lot longer in the introduction with “small talk.” I give a brief tutorial about the virtual visit. I make sure not to make any assumptions to their reactions. I ask a lot of open-ended questions. |

| R5. Make sure the patient can see and hear me clearly. I want to make as much eye contact as possible. I try to “lean in” and create a warm presence even though we may be hundreds of miles away. I make sure to ask them about the quality of the visit and if all their concerns addressed. |

| R6. Greet them. Smile! Show how happy I am to see them. I mention how wonderful it is that we can connect virtually. Ask them how things have been since we last saw each other. Then we dive into the topic of the visit. When the visit comes to an end, I wave good bye. Sometimes, I put my hand over my heart as I say good bye. |

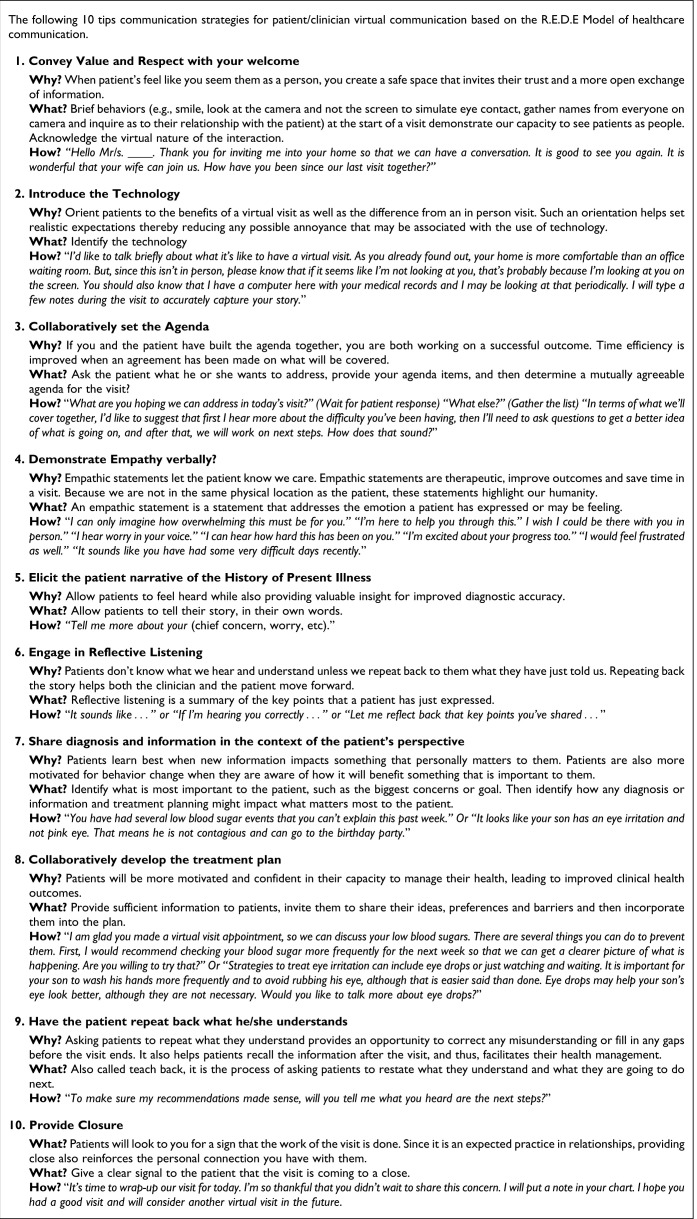

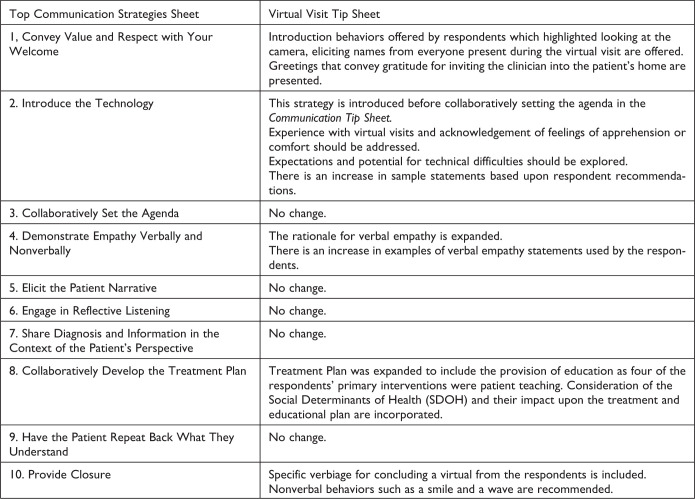

Each clinician shared some of their preferred phrases that have comforted their patients and allowed them to connect in a meaningful way. One clinician emphasized the value of being fully present at the moment in order to hear just not the facts but also the feelings and intonations conveyed by her patients’ stories. Such meaningful awareness enhanced her ability to respond more holistically to the physical and emotional needs of her patients. Several recounted how they conveyed empathy through prosody (26). They described the way they intentionally used their voice and emphasized the importance of intonation, volume, and pace in connecting with their patients. Some examples include: “Greet the patient with a warm hello.” “Offer a warm and genuine ‘hello.’” “Greet warmly!” “I change my tone of voice and rate of speed based on the patient’s expression of emotion.” “I get closer to the screen and I use my voice to slowly and softly express empathy.” “I am very intentional about how I use my voice. As a nurse, I know that my voice is an instrument in caring.” These “best practices” were incorporated into a Virtual Visit Communication Tip Sheet that has been made available to all clinicians at our organization (see Figure 2). Differences between the original tip sheet and the virtual tip sheet are included for comparison (see Figure 3). The authors suggest that rigorous research studies of these clinician-recommended practices are needed to validate their efficacy in optimizing relationship-centered care in virtual visits.

Figure 2.

Top 10 Communication Tips for Clinicians

Figure 3.

Differences in Virtual Visit Tip Sheet from Top Communication Strategies.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has forever changed how health care will be delivered. It has shown us that telehealth services are an acceptable adjunct to in-person visits. Relationship-centered virtual visits require clinicians to be intentional and deliberate in doing all that is known to be effective with in-person visits to optimize the advantages of telemedicine. Patients should not have to compromise the relationship in exchange for the ease of access or safety afforded by telemedicine.

Based on our review of the literature and the recommendations of high-volume users of virtual visits who are perceived by patients as relationally centered, there are communication techniques that are easily transferrable to the virtual world. An optimal relationship-centered webside manner emphasizes mindfulness, verbal empathy, and sentiment-congruent prosody throughout the visit. Qualitative research is needed to examine the incremental contributions these relationship-centered webside manner skills can have on establishing a relationship, acknowledging suffering, and promoting healing.

Author Biographies

Mary Beth Modic is a clinical Nurse specialist in Diabetes Care. She is also faculty and Meta-Trainer for the R.E.D.E. to Communicate, Foundations in Healthcare Communication (FHC) Course.

Katie Neuendorf is a meta trainer for FHC. She has been instrumental in the creation of multiple communication courses which cover topics such as delivering bad news and talking to patients about pain and pain management.

Amy K Windover is the author of the R.E.D.E. model. She is a member of the team that originated the R.E.D.E. to communicate series of experiential skill courses designed to improve patient experience, clinical health outcomes and caregiver experience.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board waived approval. Clinician interviewees provided informed consent to allow information to be incorporated into content development including this manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Mary Beth Modic, DNP, APRN-CNS, CDCES, FAAN  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3456-6390

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3456-6390

Katie Neuendorf, MD, FAAHPM  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0472-4180

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0472-4180

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Get your clinic ready for COVID-19. 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020, from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinic-preparedness.html.

- 2. National Public Radio. During coronavirus outbreak, virtual doctor visits are encouraged. NPR Morning Edition. 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from: https://www.cityclub.org/forums/2020/05/22/how-will-the-pandemic-change-healthcare-delivery.

- 3. American Ophthalmology Association. New recommendations for urgent and non-urgent patient care. 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020, from: https://www.aao.org/headline/new-recommendations-urgent-nonurgent-patient-care.

- 4. City Club of Cleveland. How will the pandemic change healthcare delivery? 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from: https://www.cityclub.org/forums/2020/05/22/how-will-the-pandemic-change-healthcare-delivery.

- 5. Tuckson R, Edmunds M, Hodgkins M. Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1585–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dzau VJ, McClellan M, McGinnis JM, Burke S, Coye M. Vital directions for health and healthcare: priorities from a National Academy of Medicine. JAMA. 2017;317:1461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Silverman B. Physician behavior and bedside manners: the influence of William Osler and the John Hopkins School of Medicine. Proc (Bayl Univ Med). 2012;25:58–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Teichert E. Training docs on ‘webside manner’ for virtual visits. Modern Healthcare. 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2020, from: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160827/MAGAZINE/308279981

- 9. Gonzalez R. Telemedicine is forcing doctors to learn ‘webside manner’. 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2020, from: https://www.wired.com/story/telemedicine-is-forcing-doctors-to-learn-webside-manner/

- 10. McConnochie KM. Webside manner: a key to high-quality primary care telemedicine for all. Telemed J e-Health. 2019;25:1007–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matusitz J, Breen GM. Telemedicine: its effect on health communication. Health Commun. 2007;21:73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fathi JT, Modin HE, Scott JD. Nurses advancing telehealth services in the era of healthcare reform. OJIN. 2017;22:1320–25 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Windover A, Boissy A, Rice T, Gilligan T, Velez VJ, Merlino J. The REDE model of healthcare communication: optimizing relationship as a therapeutic agent. J. Patient Exp. 2014;21:8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Terry C, Cain J. The emerging issue of digital empathy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henry BW, Block DE, Ciesla JR, McGowan BA, Vozenilek JA. Clinician behaviors in telehealth care delivery: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22:869–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheshire WP, Barrett KM, Eidelman BH, Mauricio EA, Huang JF, Freeman WD, et al. Patient perception of physician empathy in stroke telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;1–10. Published online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGrail M, Ahuja M, Leaver C. Virtual visits and patient-centered care: results of a patient survey and observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robinson MD, Branham AR, Locklear A, Robertson S, Gridley T. Measuring satisfaction and usability of Facetime for virtual visits in patients with uncontrolled diabetes. Telemed J E Health. 2015;22:138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kelly JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient—clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Donelan K, Barretto E, Sossong S, Michael C, Estrada JJ, Cohen AB, et al. Patient and clinician experiences with telehealth for patient follow-up care. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25:40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Richards D, Caldwell P. Improving health outcomes sooner rather than later via an interactive website and virtual specialist. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2018;22:1699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Houwelingen C, Moerman A, Ettema R, Kort H, Ten Cate O. Competencies required for nursing telehealth activities: a Delphi-study. Nurs Educ Today. 2016;39:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gordon HS, Solanki P, Bokhour BG, Gopal RK. “I’m not feeling like I’m part of the conversation”: patients’ perspectives on communicating in clinical video telehealth visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020, from: 10.1007/s11606-020-05673-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. Neuman M, Edelhauser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86:996–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boissy A, Windover A, Bokar D, Karafa M, Neuendorf K, Frankel RM, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:755–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiao B, Bone D, Van Segbroeck M, Imel ZE, Atkins DC, Georgiou P, et al. Modeling therapist empathy through prosody in drug addiction counseling. In: 15th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Singapore, September 14-18, 2014 https://www.isca-speech.org/archive/interspeech_2014/i14_0213.html [Google Scholar]