In this systematic review, we synthesize epidemiological evidence for the association between ACEs and later justice system contact.

Abstract

Video Abstract

CONTEXT:

Given the wide-ranging health impacts of justice system involvement, we examined evidence for the association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and justice system contact in the United States.

OBJECTIVE:

To synthesize epidemiological evidence for the association between ACEs and justice system contact.

DATA SOURCES:

We searched 5 databases for studies conducted through January 2020. The search term used for each database was as follows: (“aces” OR “childhood adversities”) AND (“delinquency” OR “crime” OR “juvenile” OR criminal* OR offend*).

STUDY SELECTION:

We included all observational studies assessing the association between ACEs and justice system contact conducted in the United States.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Data extracted from each eligible study included information about the study design, study population, sample size, exposure and outcome measures, and key findings. Study quality was assessed by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for nonrandomized trials.

RESULTS:

In total, 10 of 11 studies reviewed were conducted in juvenile population groups. Elevated ACE scores were associated with increased risk of juvenile justice system contact. Estimates of the adjusted odds ratio of justice system contact per 1-point increase in ACE score ranged from 0.91 to 1.68. Results were consistent across multiple types of justice system contact and across geographic regions.

LIMITATIONS:

Most studies reviewed were conducted in juvenile justice-involved populations with follow-up limited to adolescence or early adulthood.

CONCLUSIONS:

ACEs are positively associated with juvenile justice system contact in a dose-response fashion. ACE prevention programs may help reduce juvenile justice system contacts and improve child and adolescent health.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are a set of childhood adversities, including household dysfunction and various forms of abuse and neglect, occurring before the age of 18.1 The original ACE study conducted by Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention included 7 predefined categories of childhood exposures, which have been expanded over time to include a greater number of categories and specific experiences, such as peer victimization and exposure to community violence.2,3 The ACE pyramid provides a theoretical framework to understand the impact of ACEs on poor health: traumatic childhood experiences influence future health and well-being through a pathway of disrupted neurodevelopment and social, emotional, and cognitive impairment, leading to the adoption of health-risk behaviors and physical and mental health problems, and finally resulting in early death.4

Over the past 2 decades, ACEs have emerged as a strong and policy-relevant predictor of morbidity and health-risk behaviors across the life course. The original ACE study, conducted in 1998 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente, found that ACEs are both common and associated with mortality and health-risk behaviors in the general population.5 Since then, strong associations have continually been identified between ACEs and a wide range of adverse physical and mental health outcomes as well as health-risk behaviors.6–8

Childhood trauma has also been linked to excess contact with the justice system, especially among juvenile populations.9–11 Although much of this work predates the widespread use of the ACEs questionnaire, research on the trauma-crime relationship is often relevant and applicable to the ACE framework. The frequent co-occurrence of delinquency and victimization has been documented, and justice-involved youth who have experienced poly-victimization are more likely to report being involved in delinquency than non–justice-involved youth.12,13 In multiple studies, authors have estimated that ∼25% to 30% of incarcerated youth meet the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder,10,14 and children involved with the child welfare system are also overrepresented among justice-involved youth.14,15 In their 2006 report to the National Bureau of Economic Research, Currie and Tekin16 found that childhood maltreatment doubled the risk of engaging in self-reported criminal activity. More recently, Layne et al17 identified graded relationships between the number of traumatic exposures in childhood and high-risk behaviors in later life.

The relationship between trauma and justice involvement is of particular interest to public health given the wide-ranging individual and community impacts of incarceration and policing.18,19 At the individual level, involvement with the justice system may lead to and exacerbate health disparities in substance use,20,21 infectious disease,22,23 mental illness,20,24 injury,21,25 chronic disease,26 and death.27–29 At the community level, incarceration destabilizes family structures and hampers employment and economic opportunity, political participation, and community stability.18,30 As such, justice system contact represents an important public health problem as both marker and predictor of poor individual and community well-being. Given the concentration of childhood trauma and justice system involvement in disadvantaged communities, as well as their associated public health impacts, evidence regarding the association of ACEs with justice system contact is potentially helpful for policy makers, those working with justice-involved persons, and public health practitioners alike. In this systematic review, we aim to synthesize epidemiological evidence for the association between ACEs and justice system contact (eg, arrest, conviction, recidivism, and incarceration)—specifically, the graded effects of cumulative ACE score on justice system contact in the United States.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of observational studies examining the relationship between cumulative ACE score and justice system contact in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.31,32 The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42020169637).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) exposure was or could be transformed to reflect cumulative ACE score, whether obtained directly from administration of the ACE questionnaire or extracted and calculated from secondary sources (eg, child protective services reports or institutional records); (2) the outcome was related to contact with the justice system (eg, arrest, incarceration, and felony charge) and was verified through third-party records or self-reported (see below); (3) the authors used an epidemiological design (cross sectional, cohort, or case control) and reported quantitative measures of association; and (4) the study was conducted in the United States. No restrictions based on participant incarceration status or publication date were applied. No restrictions on comparator group (or lack thereof) were applied because the primary effect of interest was the graded effect of each 1-point increase in ACE score. No restrictions were placed on the number or type of ACEs measured in each study. We restricted this systematic review to studies conducted in the United States to reduce heterogeneity resulting from (1) country-level differences in adult and juvenile justice systems33 and (2) potential differences in ACE prevalence between the United States and other high-income countries,34 both of which might represent important leverage points for law or policy intervention.

Through the course of the review, it became apparent that some samples of juvenile offenders had rather been adjudicated to alternative treatment facilities; we also included these studies if it was explicitly stated that the outcome of interest was equivalent to or an alternative to arrest or felony charge in a juvenile population. Additionally, there was one modification to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews protocol during the systematic review: whereas studies on criminal behavior (eg, sexual offending and gang involvement) were included only if verifiable through third-party records, contact with law enforcement via arrest or incarceration was deemed eligible if self-reported. The rationale for this modification was twofold: first, contact with law enforcement can theoretically be validated and may be less prone to response bias than criminal activity about which law enforcement is not yet aware; and second, community-based surveys must often rely on self-reported behavior because of practical constraints. Finally, single-item reports of arrest or incarceration are a commonly used outcome measure with acceptable test-retest reliability and validity.35

Studies were excluded if (1) the childhood trauma (exposure) measurement was not operationalized as a cumulative ACE score and could not be transformed to a cumulative ACE score; (2) the outcome measure was self-reported criminal behavior that was not verifiable through third-party records (eg, self-reported vandalism, violence, and other delinquent behaviors that did not result in contact with law enforcement); or (3) no quantitative data were reported, such as commentaries, opinion pieces, qualitative studies, letters, editorials, and reviews.

Search Strategy and Information Sources

We searched the following 5 databases from January 24 to January 30: PubMed, PsycINFO, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The Google Scholar search was limited to the first 200 results; this is consistent with previous literature on optimal search strategy36 and seeks to balance the sensitivity of Google Scholar’s search strategy against the large number of false-positives generated. The search term used for each database was as follows: (“aces” OR “childhood adversities”) AND (“delinquency” OR “crime” OR “juvenile” OR criminal* OR offend*).

Study Selection

Initial literature search and screening was performed by a graduate student in epidemiology (G.G.), and a subsample of the screened articles were assessed for accuracy by 2 investigators (G.L. and S.C.) with extensive experience in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. All search results were collected in a central database and deduplicated. Study abstracts were first screened for eligibility; we then reviewed the full text of potentially eligible articles to make a final eligibility determination. Reference lists and related article links of eligible studies were searched to identify additional potential studies for inclusion; the studies were then reviewed and assessed for eligibility.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The following data were extracted from each eligible study independently by 2 of us (G.G. and S.C.): study authors, publication year, journal, sample size, study population, study design, exposure measurement, outcome definition, outcome ascertainment, covariates, subgroups, and measures of effect reported. Discrepancies in the abstracted data were resolved through discussion and consensus building led by the senior author (G.L.). The principal summary measure of interest was the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for justice system contact given a 1-point increase in ACE score. Where possible, estimates were obtained directly from published articles. Alternatively, estimates were transformed from data presented in the published article; if neither of these was possible, data necessary for these calculations were requested from study authors. When results were reported separately by subgroup (eg, race or sex), data were abstracted separately for each subgroup.

Study quality and risk of bias were assessed by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort and case-control studies.37 Cross-sectional studies were evaluated by using a modified NOS that is based on criteria developed by Modesti et al.38 Given evidence of significant heterogeneity in the studies eligible for review, we present a qualitative synthesis of findings in the present report.

Results

Study Selection

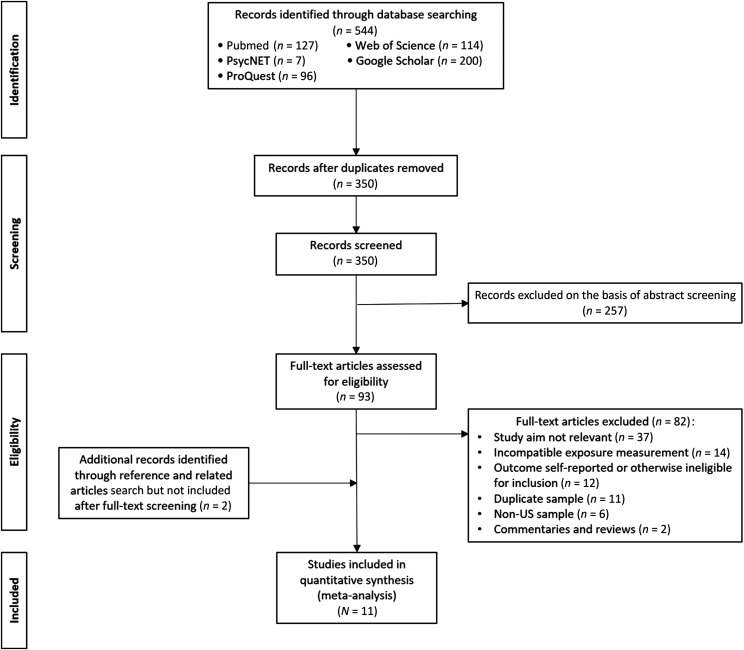

The initial search of 5 databases yielded 544 records; of them, 194 duplicate records were removed, and the remaining 350 titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by the first author. Of the 350 records, 257 were deemed not relevant; the full text of the remaining 93 records was reviewed for eligibility. Of these 93 records, 71 were excluded for (1) irrelevant study aim (n = 37); (2) incompatible exposure measurement (n = 14); (3) outcome self-reported or otherwise ineligible for inclusion (n = 12); (4) non-US sample (n = 6); and (5) commentaries and review (n = 2). In addition, 11 studies were excluded because of overlapping samples with identical outcome measures. A total of 11 studies were selected for inclusion in the final systematic review (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart: identification, review, and selection of studies related to the graded effect of ACEs on justice system contact. Adapted from Moher et al.31

Study Characteristics

Of the 11 studies evaluating the association between ACE score and justice system contact, 3 reported juvenile arrest as their primary outcome of interest,39–41 2 examined sexual offending,42,43 2 examined juvenile reoffending,44,45 1 examined serious, violent, and chronic delinquency as a juvenile,46 1 examined early juvenile offending,47 1 examined juvenile gang involvement,48 1 examined early adulthood felony charge,40 and 1 examined adult incarceration.49 A total of 15 results were included in our primary meta-analysis because of multiple outcomes being reported within a single study,40 separate reporting of results by Black and white race,39 and separate reporting of results by sex42,45 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in Meta-analysis of Graded Effects of ACEs on Justice System Contact

| Author, y | Data Source | Population | N | Study Design and/or Analysis | Study Time Period | No. ACEs Captured (Age Range): ACEs Captured (Exposure Assessment) | Outcome and Definition | Outcome Ascertainment | Covariates | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baglivio et al,47 2015 | FDJJ archival data records | All youth in Florida with an arrest history who were administered the full C-PACT and turned 18 during the study period | 64 329 | Cohort, logistic regression | January 1, 2007–December 31, 2012 | 10 (ever): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, family violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, household member incarceration score transformed from C-PACT items (administered through a semistructured interview conducted by a trained juvenile probation officer or contracted assessment staff; additional review of case file and education and child abuse records) | Membership in juvenile offending trajectory group; we extracted data on early starters compared with mid- to early starters who later desist. | JJIS data extracts were used to gather every instance of arrest for youth at each age up to age 17. | Race, sex | Each 1-point increase in ACE score was associated with a 28.7% increase in the odds of being an early starter relative to the odds of being a mid- to early starter who later desists. |

| Craig,44 2019 | FDJJ archival data records | 3-y cohort of all youth with an arrest history who completed some form of a community-based placement during the study period | 25 461 | Cohort, logistic regression | July 1, 2009–June 30, 2012 | 10 (ever): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, household substance abuse, violent treatment toward mother, parental separation or divorce, household mental illness, household member incarceration score transformed from C-PACT items (administered through a semistructured interview conducted by a trained juvenile probation officer or contracted assessment staff; additional review of case file and education and child abuse records) | Reoffending, defined as rearrest within 12 mo after completion of community-based placement | Arrest records were from FDJJ. | Race, sex, age, disadvantage, additional covariates related to antisocial peer associations, impulsivity, social bonds, youth criminal history and criminal attitudes | Each 1-point increase in ACE score was associated with a 3% increase in the odds of 12-mo rearrest. |

| Fagan and Novak,39 2018: (1) Black participant; (2) white participants | LONGSCAN study of child maltreatment (Baltimore, Chicago, San Diego, Seattle, Chapel Hill) | High-risk sample of children ages 4–6 and caregivers (based on having a history of maltreatment or considered at risk for based on parents’ low SES and maternal substance use) | 620 | Cohort, logistic regression | 1990–2002 | 10 (before age 12): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, failure to provide (ie, physical neglect), lack of supervision, caregiver intimate partner violence victimization, caregiver depression, caregiver substance use or abuse, caregiver criminality, family trauma transformed from child protective services agency records from states participating in LONGSCAN (based on child and caregiver responses to Modified Maltreatment Classification System and Conflict Tactics Scale; cumulative ACE score was winsorized at 7) | Past-year arrest at age 16 | Self-reported, primary caregiver reports | Age, sex, single parent, geographic region, poverty, other neighborhood and community covariates; analyses stratified by race | Among Black participants, each 1-point increase in ACE score was associated with a 23% increase in the odds of past-year arrest at age 16. Findings were not significant for white participants (aOR 0.91; 95% CI [0.69–1.20]). |

| Fleming and Nurius,49 2019 | Washington state BRFSS survey (2011) | State implementation of nationally representative survey conducted in collaboration with the CDC | 13 803 | Cross-sectional, Wald difference test | 2011 | 8 (before age 18): sum of participant responses to 8 CDC categories of ACEs: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, household incarceration, living with someone with serious mental illness, living with someone with substance use issues, parents divorced or separated, parents who physically hurt one another | Adult incarceration (after age 18) | Self-reported | Race, sex, education | Findings after data transformation: each 1-unit increase in ACE score was associated with an 18% increase in the odds of adult incarceration. |

| Giovanelli et al,40 2016: (1) outcome: juvenile arrest; (2) outcome: adult felony charge | Chicago Longitudinal study | Low-income, minority sample born in high-poverty neighborhoods in Chicago from 1979 to 1980 | 1200 | Cohort, logistic regression | 1986 (start of study) to 2002 (age 22–24 follow-up survey) | 9 (before age 18): physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, prolonged absence of parent or divorce of parents, death of family member or close friend or relative, frequent family conflict, problems of substance abuse of parent, witness to a shooting or stabbing, violent crime victimization (assessed in survey at 22–24 y; physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect items obtained from administrative records) | Two outcomes: (1) juvenile arrest (ages 10–18) and (2) felony charge (ages 18–24) | Juvenile arrest records were obtained from petitions to Cook County Juvenile Court and 2 other Midwestern locations. Felony charges were taken from federal prison records as well as documented histories in state, county, and circuit courts. | Race, sex, family ecology of risk, CPC intervention status | Findings after data transformation: each 1-unit increase in ACE score was associated with a 13% increase in the odds of juvenile arrest. Findings were not significant for felony charge (aOR 1.04; 95% CI [0.97–1.12]). |

| Kowalski,45 2019: (1) male participants; (2) female participants | Archival records from juvenile justice agency in Washington state | Youth on probation in Washington state who completed the PACT full assessment during the study period | 35 442 | Cohort, logistic regression | December 2003–June 2017 | 10 (ever): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, domestic violence, household substance abuse, household mental health problems, parental separation or divorce, incarceration of a household member score transformed from C-PACT items (administered through a semistructured interview conducted by a trained juvenile probation officer or contracted assessment staff; additional review of case file and education and child abuse records) | Reoffending, defined as a new felony, misdemeanor, violent, property, drug, or sex offense at 12 mo | Records were from Washington state (standard 18-mo follow-up period). | Race, sex, age, mental health status, substance use, risk level | Among male participants, each 1-point increase in ACE score was associated with a 7% increase in the odds of 12-mo reoffending. Among female participants, each 1-point increase in ACE score was associated with a 4% increase in the odds of 12-mo reoffending. |

| Levenson et al,42 2017: (1) male participants; (2) female participants | FDJJ archival data records | Youth who aged out of the juvenile justice system (turned 18 y old) and who were assessed with the C-PACT full assessment during the study period | 89 045 | Case control, logistic regression | January 1, 2007–December 31, 2015 | 10 (ever): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, family violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, household member incarceration score transformed from C-PACT items (administered through a semistructured interview conducted by a trained juvenile probation officer or contracted assessment staff; additional review of case file and education and child abuse records) | Juvenile sexual offending (misdemeanor or felony offenses), defined as arrest ≥1 time for a sexual offense before age 18 | Arrest records were from FDJJ. | None | Findings after data transformation: among male participants, each 1-point increase in ACE score is associated with a 1% increase in the odds of juvenile sexual offending versus nonsexual offending. Among female participants, each 1-unit increase in ACE score is associated with a 4% increase in the odds of juvenile sexual offending versus nonsexual offending. |

| Naramore et al,43 2017 | FDJJ archival data records | All youth in Florida ages with an arrest history who were administered the full C-PACT and were 11.4–22.5 y at the time of their last assessment | 64 329 | Cross sectional, logistic regression | December 14, 2005–December 30, 2012 | 10 (ever): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, family violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, household member incarceration score transformed from C-PACT items (administered through a semistructured interview conducted by a trained juvenile probation officer or contracted assessment staff; additional review of case file and education and child abuse records) | Arrest for trading sex (ie, “offer to commit, or to commit, or to engage in, prostitution, lewdness, or assignation” or “aid, abet, or participate in any of the acts or things enumerated in this subsection”43) | Arrest records were from FDJJ. | None | Findings after data transformation: each 1-point increase in ACE score is associated with a 68% increase in the odds of being arrested for trading sex compared to arrest for other offenses. |

| Perez et al,46 2018 | FDJJ archival data records | Youth who aged out of the juvenile justice system (turned 18 y old) and who were assessed with the C-PACT full assessment during the study period | 64 329 | Case control, logistic regression | January 1, 2007–December 31, 2012 | 9 (ever): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, witnessing household violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, household member incarceration score transformed from C-PACT items (administered through a semistructured interview conducted by a trained juvenile probation officer or contracted assessment staff; additional review of case file and education and child abuse records) | SVC delinquency, defined as committing ≥3 serious felony offenses, with at least 1 violent offense | Arrest records were from FDJJ. | Race, sex, SES | Each 1-point increase in ACE score is associated with a 30% increase in the odds of a juvenile offended being classified as an SVC offender. |

| Stinson et al,41 2016 | Inpatient forensic psychiatric facility in the Midwestern United States | Selected participants had commitments for violent or sexual offending and a length of admission ≥1 y at the time of data collection of 2 nonoverlapping time samples in 2007 and 2012. | 381 | Cross sectional, logistic regression | 2007, 2012 | 6 (during developmental years): verbal and/or emotional abuse, physical abuse, intrafamilial sexual abuse, extrafamilial sexual abuse, neglect, parental substance abuse (coded from the social service reports generated at admission and annually by facility personnel; experiences were self-reported by clients, reported by corroborating family members, and/or records obtained from state investigations of reported maltreatment) | Juvenile arrest, defined as arrest before age 19 | Available social service records | None | Each 1-point increase in ACE score is associated with 34% higher odds of juvenile arrest among violent and sexual offenders. |

| Wolff et al,48 2020 | FDJJ archival data records | Youth who aged out of the juvenile justice system (turned 18 y old) and who were assessed with the C-PACT full assessment during the study period but who were not involved with a gang at time of first assessment and who had information on race and/or ethnicity | 104 266 | Cohort; rare-events logistic regression | January 1, 2007–December 31, 2017 | 10 (ever): emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, family violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, household member incarceration score transformed from C-PACT items (administered through a semistructured interview conducted by a trained juvenile probation officer or contracted assessment staff; additional review of case file and education and child abuse records) | Verified gang involvement; only youth for whom there exists written documentation from law enforcement certifying them as gang involved (as per state statute) were classified as verified. | Law enforcement documentation | Race, sex, age | Each 1-point increase in ACE score is associated with 14% higher odds of gang association among juvenile offenders. |

BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CI, confidence interval; C-PACT, Community Positive Achievement Change Tool; FDJJ, Florida Department of Juvenile Justice; JJIS, xxx; LONGSCAN, Longitudinal Studies on Child Abuse and Neglect; PACT, Positive Achievement Change Tool; SES, socioeconomic status; SVC, serious, violent, and chronic.

Study Quality

Eight of the 11 eligible studies adjusted for important covariates including race, sex, community and neighborhood factors, and risk behaviors. Of the 3 studies that did not, the absence of covariate adjustment in 2 studies was explained by the need for data transformation to assess the primary relationship of interest.42,43 The average Newcastle-Ottawa Score for cohort studies was 7.75 of 9 (range 7–8), with most studies losing 1 point because of a lack of sample representativeness. In the NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies, the average score was 7.2 of 10 (range 5–9). Among all studies, only 1 was performed in a representative state community sample49; all other studies were conducted in juvenile populations (n = 7), in samples of children at high risk for maltreatment (n = 2), or in an adult population with a history or violent or sexual offenses (n = 1). In 7 studies, researchers used comprehensive data from state juvenile justice populations; 1 study used a state community sample; 2 studies used “high-risk” samples in selected US cities; and 1 study used a sample drawn from an inpatient treatment facility. Notably, data from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (n = 6) were overrepresented among included studies. Ascertainment of exposure and outcome measurements were generally strong because of stringent inclusion criteria in the present review. Assessments of study quality are available in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

Summary of Findings

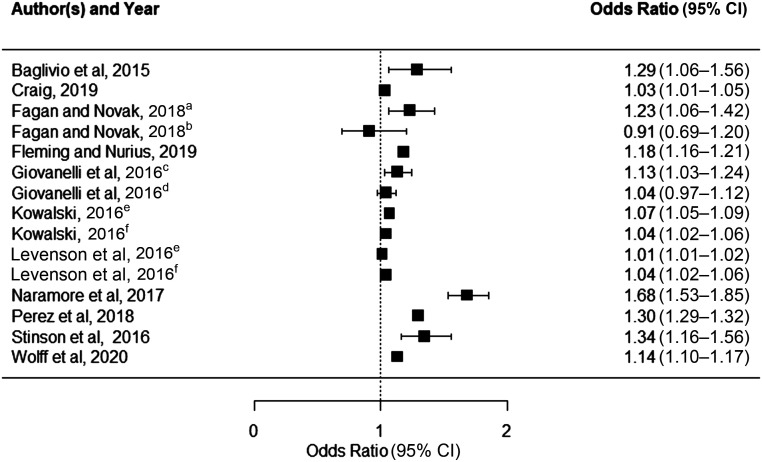

Of the 15 results from 11 studies included in our primary analysis, 13 revealed statistically significant positive associations between ACE score and justice system contact, whereas 2 indicated no significant association39,40 (Fig 2). The estimated aORs for justice system involvement ranged from 0.91 to 1.68 per 1-point increase in ACE score. In most studies (10 of 11) included in our review, authors examined outcomes in youth and young adulthood. We found that a 1-point increase in ACE score is associated with 9% lower to 68% higher odds of juvenile justice system contact. Further research is needed to reliably summarize the relationship between ACE score and justice system contact in adulthood and later life.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot, estimated aORs, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the association between each 1-point increase in ACE scores and overall justice system contact. a Black participants. b White participants.c Outcome: juvenile arrest. d Outcome: adult felony charge. e Male participant. f Female participant.

In 7 out of the 10 studies examining juvenile outcomes, authors examined outcomes in statewide juvenile populations,42–48 increasing confidence in the validity of our primary findings. Results were consistent in the direction of association and significance across geographic regions within the United States.

Discussion

We found compelling and consistent epidemiological evidence for a graded relationship between ACE score and juvenile justice system contact in the United Status. However, estimates of the overall relationship between ACE score and justice system contact across the life course were limited by the lack of studies in which authors examined adult justice involvement and should be interpreted with caution. Because the ACE framework explicitly takes a life course perspective, the association between ACE score and justice system contact in adulthood and later life is a promising area for future investigation. An understanding of the life course impacts of ACEs on justice system contact is important for policy makers and pediatric providers alike given the potential long-ranging impacts of intervening on these exposures in childhood.

Our findings support previous research identifying links between childhood trauma and subsequent contact with the justice system.14,16,17 Alongside previous literature linking both ACEs and incarceration to poor health, these findings provide empirical support for the relationship between ACE exposure and justice system contact. Further research is needed to assess the pathways through which victimization leads to justice system contact and how each of these in turn may contribute to poor health, including relationships between victimization and perpetration12 and behavioral and mental health risks of victimization.13

Our findings in this review are particularly salient to pediatric providers for several reasons. First, given evidence of associations between ACEs and juvenile justice involvement, pediatric providers may oversee patients both at the time of exposure (experience of ACEs) and outcome (justice system contact). Thus, pediatric providers represent an important stakeholder in interventions targeting both exposure and subsequent risk of justice system involvement. Second, the ACE framework identifies childhood as a highly susceptible period, during which exposure to adverse experiences “gets under the skin” to affect outcomes across the life course. Thus, intervention or guidance by pediatric providers during this critical period can potentially have benefits far beyond childhood and adolescence.

In the course of our review, we identified evidence of publication bias and significant heterogeneity across the studies reviewed. The publication bias issue may be mitigated by characteristics of the studies included in this review: 8 of 11 studies were in large data sets (range: 13 803–104 266 participants), all of which were population samples of juvenile offenders at the state level. It is common to find significant heterogeneity in outcomes of observational studies partly because of differences in the study designs, study samples, analytical approaches, and confounding factors controlled for. As more evidence becomes available, quantitative synthesis of the association between ACE score and various forms of justice system involvement may be of particular interest.

There are several important considerations that should be raised in light of our findings. First, both ACEs and contact with the justice system in the United States are patterned by socioeconomic factors.50–52 In the Fagan and Novak39 study included in our review, results were significant for Black participants but not for white participants. Further research is needed to evaluate the consistency of effect-size differences by race and should consider whether and how overpolicing of economically disadvantaged areas may confound observed associations between ACEs and justice system contact. As the prevalence of ACEs in the United States changes over time,34 it is also important to observe whether disparities in prevalence and associations with justice system context persist. Assessment of the ACE–justice system relationship by sociodemographic factors in other countries may also serve to identify US-specific drivers of observed disparities.

Second, the generalizability of our findings may be limited because most studies in this review examined justice-involved or underresourced populations. Although the original ACE study was conducted in a predominantly white, college-educated sample with private health insurance, subsequent studies have established strong associations between trauma and poor health in minority and disadvantaged populations.53–57 In a 2006 report, Currie and Tekin16 found that the effects of trauma were found to be particularly harmful to children from low socioeconomic status families. Effect-size estimates from this review may therefore be larger than the true effects in the general population.

However, our findings are in line with a large body of literature identifying negative life course health consequences of ACE exposure across demographic characteristics and socioeconomic context.5,6 Given unequal ACE distributions by race, sex, and sexual orientation50 and strong gradients by childhood socioeconomic status,58 research on ACEs alongside other markers of economic and social disadvantage is of particular importance. Particular attention should be paid to pathways through which these factors intersect with ACEs and justice system involvement in affecting health outcomes in adulthood and later life. Finally, in 9 of 11 studies included in this review, authors calculated the exposure of interest, ACE score, on the basis of a review of existing files or records. Further research is needed to confirm that these findings hold when ACEs are self-reported through the original ACE questionnaire.

Overall, we find epidemiological evidence to support the hypothesis that ACE score is positively and significantly associated with the risk of juvenile justice system contact. Although further research is needed to confirm these associations in older populations, study findings are in line with existing theory regarding the pathways through which ACEs affect health outcomes across the life course. Adding to the existing literature about the impact of ACEs on health and health behaviors across the life course, our findings indicate that targeting ACEs may have positive impacts on individual and community health through the reduction of contact with the justice system, particularly in adolescence and young adulthood.

Glossary

- ACE

adverse childhood experience

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Footnotes

Ms Graf helped to conceptualize and design the study, performed initial literature search and screening, performed data extraction and data analyses, and wrote an initial draft of the manuscript; Mr Chihuri helped to conceptualize and design the study, assessed a subsample of screened articles for accuracy, and performed data extraction and data analyses; Ms Blow helped to conceptualize and design the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and revised and edited manuscript drafts for clarity and intellectual content; Dr Li conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, assessed a subsample of screened articles for accuracy, and revised and edited manuscript drafts for clarity and intellectual content; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This trial has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) (identifier CRD42020169637).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported in part by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant 1 R49 CE002096) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R21 HD098522). The contents of the article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the funding agency. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Anda R, Block R, Felitti V; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Kaiser Permanente . Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, Hamby S. A revised inventory of adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;48:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ, Jones LM, Henly M. Strengthening the predictive power of screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in younger and older children. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;107:104522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The ACE pyramid. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Facestudy%2Fabout.html. Accessed November 30, 2020

- 5.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalmakis KA, Chandler GE. Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: a systematic review. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(8):457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–e366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petruccelli K, Davis J, Berman T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;97:104127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamberlain P, Moore KJ. Chaos and trauma in the lives of adolescent females with antisocial behavior and delinquency. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2002;6(1):79–108 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford JD, Chapman JF, Hawke J, Albert D. Trauma Among Youth in the Juvenile Justice System: Critical Issues and New Directions. Delmar, NY: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice; 2007:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Widom CS, Maxfield MG. A prospective examination of risk for violence among abused and neglected children. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;794(1):224–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuevas CA, Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Ormrod RK. Juvenile delinquency and victimization: a theoretical typology. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(12):1581–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(6):545–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dierkhising CB, Ko SJ, Woods-Jaeger B, Briggs EC, Lee R, Pynoos RS. Trauma histories among justice-involved youth: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vidal S, Connell CM, Prince DM, Tebes JK. Multisystem-involved youth: a developmental framework and implications for research, policy, and practice. Adolesc Res Rev. 2019;4(1):15–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currie J, Tekin E. Does Child Abuse Cause Crime? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Layne CM, Greeson JK, Ostrowski SA, et al. Cumulative trauma exposure and high risk behavior in adolescence: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set. Psychol Trauma. 2014;6(suppl 1):S40 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):214–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnert ES, Perry R, Morris RE. Juvenile incarceration and health. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(2):99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vermeiren R, Jespers I, Moffitt T. Mental health problems in juvenile justice populations. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(2):333–351, vii–viii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sedlak AJ, McPherson KS. Youth’s Needs and Services. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2010:10–11 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Workowski KA, Berman SM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(suppl 3):S59–S63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases among correctional inmates: transmission, burden, and an appropriate response. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):974–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safran MA, Mays RA Jr., Huang LN, et al. Mental health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):1962–1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris RE, Harrison EA, Knox GW, Tromanhauser E, Marquis DK, Watts LL. Health risk behavioral survey from 39 juvenile correctional facilities in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17(6):334–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):912–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coffey C, Veit F, Wolfe R, Cini E, Patton GC. Mortality in young offenders: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326(7398):1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison–a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Mileusnic D. Early violent death among delinquent youth: a prospective longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1586–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Travis J, Waul M. Prisoners Once Removed: The Impact of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families, and Communities. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269, W64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner P, Sawyer W. States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2018. Northampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finkelhor D. Trends in adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in the United States. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;108:104641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huizinga D, Elliott DS. Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. J Quant Criminol. 1986;2(4):293–327 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells GA, Tugwell P, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, et al.; ESH Working Group on CV Risk in Low Resource Settings . Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fagan AA, Novak A. Adverse childhood experiences and adolescent delinquency in a high-risk sample: a comparison of white and black youth. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2018;16(4):395–417 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giovanelli A, Reynolds AJ, Mondi CF, Ou S-R. Adverse childhood experiences and adult well-being in a low-income, urban cohort. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20154016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stinson JD, Quinn MA, Levenson JS. The impact of trauma on the onset of mental health symptoms, aggression, and criminal behavior in an inpatient psychiatric sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;61:13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levenson JS, Baglivio M, Wolff KT, et al. You learn what you live: prevalence of childhood adversity in the lives of juveniles arrested for sexual offenses. Adv Soc Work. 2017;18(1):313–334 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naramore R, Bright MA, Epps N, Hardt NS. Youth arrested for trading sex have the highest rates of childhood adversity: a statewide study of juvenile offenders. Sex Abuse. 2017;29(4):396–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craig JM. The potential mediating impact of future orientation on the ACE–crime relationship. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2019;17(2):111–128 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kowalski MA. Adverse childhood experiences and justice-involved youth: the effect of trauma and programming on different recidivistic outcomes. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2019;17(4):354–384 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perez NM, Jennings WG, Baglivio MT. A path to serious, violent, chronic delinquency: the harmful aftermath of adverse childhood experiences. Crime Delinq. 2018;64(1):3–25 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baglivio MT, Wolff KT, Piquero AR, Epps N. The relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and juvenile offending trajectories in a juvenile offender sample. J Crim Justice. 2015;43(3):229–241 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolff KT, Baglivio MT, Klein HJ, Piquero AR, DeLisi M, Howell JC. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and gang involvement among juvenile offenders: assessing the mediation effects of substance use and temperament deficits. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2020;18(1):24–53 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fleming CM, Nurius PS. Incarceration and adversity histories: modeling life course pathways affecting behavioral health. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90(3):312–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nurius PS, Green S, Logan-Greene P, Longhi D, Song C. Stress pathways to health inequalities: embedding ACEs within social and behavioral contexts. Int Public Health J. 2016;8(2):241–256 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagan J, Albonetti C. Race, class, and the perception of criminal injustice in America. Am J Sociol. 1982;88(2):329–355 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brewer RM, Heitzeg NA. The racialization of crime and punishment: criminal justice, color-blind racism, and the political economy of the prison industrial complex. Am Behav Sci. 2008;51(5):625–644 [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Ravello L, Abeita J, Brown P. Breaking the cycle/mending the hoop: adverse childhood experiences among incarcerated American Indian/Alaska Native women in New Mexico. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29(3):300–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung EK, Mathew L, Elo IT, Coyne JC, Culhane JF. Depressive symptoms in disadvantaged women receiving prenatal care: the influence of adverse and positive childhood experiences. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(2):109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mersky JP, Topitzes J, Reynolds AJ. Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: a cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(11):917–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waite R, Davey M, Lynch L. Self-rated health and association with ACEs. J Behav Health. 2013;2(3):197–205 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi J-K, Wang D, Jackson AP. Adverse experiences in early childhood and their longitudinal impact on later behavioral problems of children living in poverty. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;98:104181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halfon N, Larson K, Son J, Lu M, Bethell C. Income inequality and the differential effect of adverse childhood experiences in US children. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7S):S70–S78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]