Abstract

In this case report, we discuss a patient presenting with parkinsonism followed by a non-amnestic dementia with aphasic clinical features, as well as frontal dysexecutive syndrome. There was a family history of dementia with an autopsy diagnosis of “Pick’s disease” in the proband’s father. Neuroimaging of the patient revealed focal and severe temporal lobe and lesser frontoparietal lobe atrophy. At autopsy, there was severe frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Histologic evaluation revealed an absence of tau or transactivation response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP) pathology but rather severe Lewy body deposition in the affected cortices. Genetic phenotyping revealed a novel missense mutation (p.E83Q) in exon 4 of the gene encoding α-synuclein (SNCA). This case study presents a patient with a novel SNCA E83Q mutation associated with widespread Lewy body pathology with prominent severe atrophy of the frontotemporal lobes and corresponding cognitive impairment.

Keywords: case report, dementia, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Lewy bodies, parkinsonism

INTRODUCTION

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is defined as progressive cognitive decline often with impaired attentional, executive function, and visuospatial abilities, with co-occurrence of core clinical features, including fluctuating symptoms, persistent visual hallucinations, rapid eye movement (REM) behavior disorder, and spontaneous parkinsonism features.1 However, concordance between clinical and pathological diagnoses is highly variable, with large-scale autopsy studies demonstrating low sensitivity for the clinical diagnosis of DLB.2 Furthermore, adding complexity, older patients may present clinical symptoms that simultaneously meet the consensus criteria for more than one neurodegenerative diagnosis.3 It remains unclear whether Parkinson’s disease (PD), Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), and DLB represent a continuum of one disorder or whether they are distinct from each other. Distinguishing between DLB and PDD, clinically, relies on using the timing of dementia diagnosis in relation to onset of motor symptoms (one year or less). Due to challenges in diagnosis and the overlap with other neurodegenerative diseases, the genetics underlying DLB remain largely elusive. The majority of DLB cases are sporadic; however, there is a strong genetic component in families from Mendelian studies, of which genetic variations in SNCA, GBA, LRRK2, and SCARB2 have been implicated.4

Here we present a case report with a novel missense mutation (p.E83Q) in exon 4 in the gene encoding α-synuclein (SNCA). The proband had a family history of “Pick’s disease,” presenting with parkinsonism followed quickly, within one year, by progressive non-amnestic dementia. Clinical history and neuroimaging findings were suggestive of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with parkinsonism symptoms. At autopsy, examination revealed a severe frontotemporal lobar degeneration pattern with severe and widespread Lewy body pathology in the affected cortices.

CLINICAL SUMMARY

The patient was a 59-year-old left-handed woman with 16 years of education, a past medical history of depression, and a family history of “Pick’s disease.” She had progressive motor and cognitive impairment. The motor impairment described initially as psychomotor slowing was reported to have started several months (less than 12 months) prior to non-amnestic cognitive changes. There was progressive worsening of the motor symptoms consistent with parkinsonism, which was seen in right non-dominant side primarily. The patient worked in management, had progressive difficulty to complete projects in a timely manner at work, and was terminated from her position about one year after the first symptoms. Her psychomotor slowing impacted her driving skills, and she stopped driving around the same time as her termination from work. The patient moved into assisted living 1.5 years after the onset of symptoms, and her daughter managed all her finances. She began to use a walker due to frequent falls. She was given medications for parkinsonian symptoms, such as carbidopa–levodopa and amantadine, and started on rivastigmine for cognitive impairment. She presented for the first time to a neurobehavioral/memory clinic two years after her initial symptoms. The primary cognitive deficits that the family noticed were difficulty with word-finding and following directions. Initial neuropsychological testing revealed not only primarily dysexecutive features but also difficulty with language, particularly in picture naming, and retrieval memory impairment. The patient’s initial Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score was 14. Her neurological examination revealed signs of muscular hypotonia, slowed speech with frequent pauses, masked facies, slowed fine motor skills with finger tapping/heel tapping, and inability to perform rapid alternating movements. In addition, she exhibited bilateral dyskinesia in the upper and lower extremitites and trunk, which were presumably secondary to dopaminergic therapy. There were no reported hallucinations. The patient had no bedpartner to report dream-enactment behavior, but vivid dreams were reported. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed bilateral severe atrophy of the anterior temporal lobes and moderate bilateral atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes. The patient’s father was previously part of a study and was reported to have had a non-amnestic dementia syndrome that was diagnosed as “Pick’s disease” at autopsy. Given the clinical information, imaging, and family history, a presumptive diagnosis of FTD with parkinsonism due to tauopathy was made.

Over the next two years the patient experienced motor and cognitive decline. She was maintained on rivastigmine for cognitive impairment and amantadine for parkinsonism. She used a rolling walker for ambulation. Eventually, she was placed in an extended care facility. She had episodes of agitation and at one point was making inappropriate sexual advances with male staff members. Medications included alprazolam, mirtazapine, and quetiapine, added for anxiety, sleep difficulty, and agitation. Her verbal communication skills declined rapidly. She developed several urinary tract infections, which led to episodes of delirium and reported posturing. She had intermittent clonus and eventually became wheelchair-bound three years after initial symptoms, then bed-bound. She had a witnessed seizure and was placed onto the control with an antiepileptic drug. She had progressive swallowing difficulty and weight loss, and eventually died while under hospice care approximately four years after her initial symptoms at the age of 63 years.

In retrospect, the patient was suffering from cognitive changes that led to her termination from work and cessation from driving; therefore, the authors designate the onset of dementia to be at that time within 12 months of her first symptoms of parkinsonism.

PATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS

Macroscopic appearance

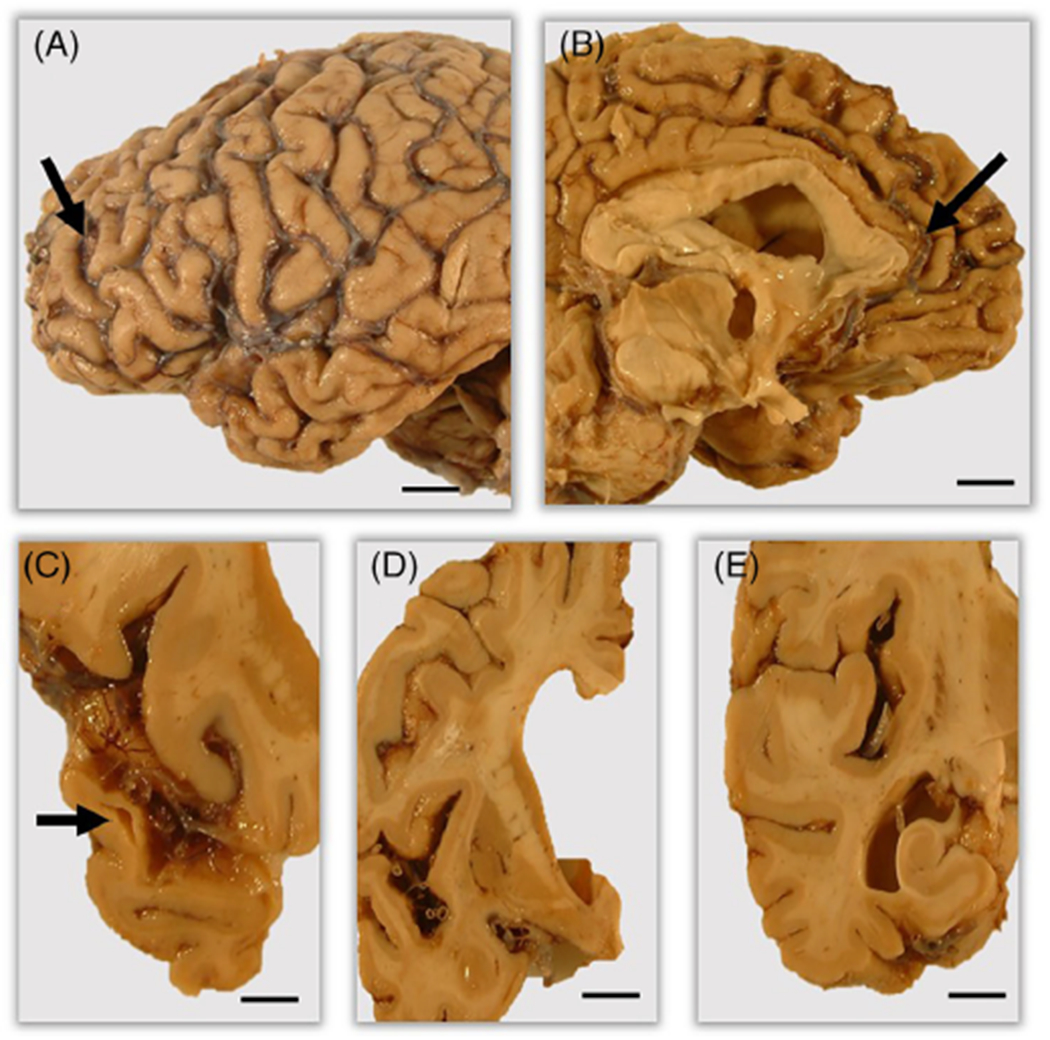

The postmortem interval at autopsy was 13 h, and the whole fresh brain weighed 1057 g. At that time, the brain was bisected in the sagittal plane. The entire left half of the brain was fixed in 10% buffered-formalin and used for neuropathological examination, and the entire right half of the brain was frozen for biological research purposes. Moderate-to-severe atrophy was primarily observed in the left frontal and temporal lobes, the atrophy most severe at the anterior temporal pole. After coronal sectioning into 1-cm slabs, thinning of the cortical ribbon was observed in the temporal lobe. There was relative sparing of the parietal and occipital lobes. Severe ventricular dilation and atrophy of the amygdala and caudate nucleus were noted, with white matter atrophy. Hippocampal atrophy was mild (Fig. 1). Both the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus showed severe depigmentation. Assessment of the vertebral, basilar, and posterior, middle and anterior cerebral arteries, and their proximal branches showed mild atherosclerosis. No other abnormalities were noted involving the cerebral blood vessels. Macroscopic observation of the cerebellum showed no unusual appearance.

Fig 1.

Macroscopic findings of the brain. Outer views of lateral (A) and medial (B) sides display moderate to severe cortical atrophy (arrows) predominantly involving the frontal and temporal lobes. Coronal slices exhibit moderate to severe atrophy of the temporal lobe (C, arrow), severe ventricular dilatation and severe atrophy of the amygdala (D), and mild atrophy of the hippocamus (E). Scale bars: 5 mm (A–E).

Microscopic appearance

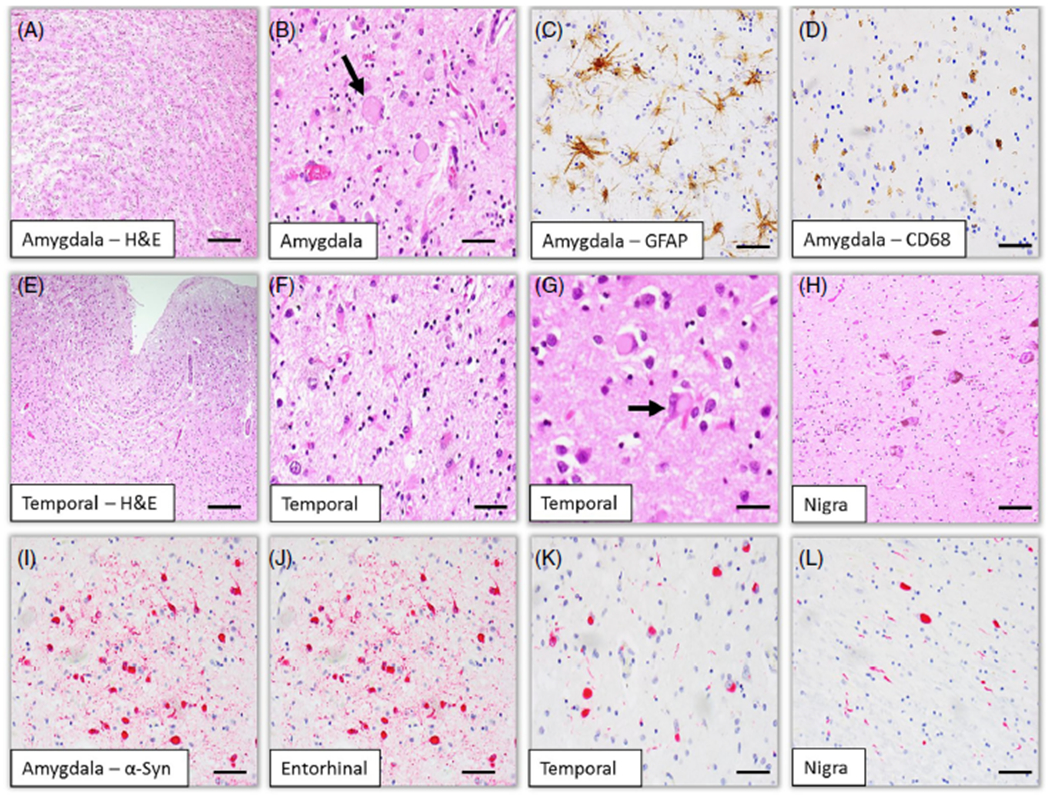

On sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), there was severe neuronal loss, gliosis, and tissue rarefraction, as well as severe superficial spongiform changes in the cortices of the middle temporal gyrus, anterior temporal pole, and cingulate gyrus, and the entorhinal cortex. Cortical neurons showed various degenerative changes, including achromatic (ballooned) neurons, consisting of a large soma and eccentric nucleus, and an abundant number of eosinophilic, glassy, cytoplasmic inclusion bodies. Severe extensive degenerative changes were also noted in the amygdala accompanied by astrocytosis and microgliosis (Fig. 2). The caudate nucleus and putamen showed gliosis without apparent neuron loss, and the thalamus was relatively preserved. In the cerebellum, the cortex and white matter were unremarkable. In the brainstem, the substantia nigra showed severe neuronal loss associated with appearance of pigment-laden macrophages and significant gliosis, lacking typical Lewy bodies on HE-stained sections.

Fig 2.

Histological (A, B, E-H) and immunohistochemical (C, D, I-L) findings of the brain. Histological findings show severe neuronal loss and spongiform changes associated with astrocytosis and microgliosis involving the temporal lobe including the amygdala (A, C–F). Ballooned neurons and eosinophilic ytoplasmic inclusions are noted (B, G). Severe degeneration is observed in the substantia nigra (H). Phosphorylated α-synuclein immunohistochemistry reveals numerous Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in the amygdala (I), the entorhinal (J) and temporal (K) cortices, and the substantial nigra (L). Immunohistochemistry for GFAP (C) and (CD68 (D) reveals reactive astrocytosis and microgliosis, respectively. Scale bars: 200 μm (A), 200 μm (E), 50 μm (B–D, F–L).

Immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein revealed widespread immunoreactive Lewy bodies and neurites. Numerous Lewy bodies and neurites were observed in the brainstem, and cortical and subcortical matter of the cerebrum (Fig. 2). Lewy bodies were counted in a 1-mm2 area of the greatest density within cortical and subcortical regions (Table 1). Frequent appearance of neuronal inclusions in multiple neocortical brain regions is consistent with the pathological diagnosis of DLB of neocortical type.

Table 1.

Lewy body count and severity based on the greatest density per 1 mm2 area

| Brain regions | Lewy body count | Severity† |

|---|---|---|

| Entorhinal cortex | 64 | +++ |

| Amygdala | 55 | +++ |

| Midfrontal cortex | 52 | +++ |

| Middle temporal cortex | 23 | +++ |

| Cingulate cortex | 20 | +++ |

| Basal ganglia | 18 | ++ |

| Inferior parietal lobule | 16 | ++ |

| Inferior orbital frontal cortex | 10 | ++ |

| Thalamus | 7 | ++ |

| Anterior temporal pole | 6 | ++ |

| Hippocampus (CA1 sector) | 6 | ++ |

| Substantia nigra | 2 | + |

| Hippocampus (dentate gyrus) | 0 | − |

| Cerebellum | 0 | − |

Graded as none (−), mild (+), moderate (++), and severe (+++).

Additional stains were completed for differential pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and tauopathy. Immunohistochemistry for transactivation response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43) and fused-in-sarcoma (FUS) revealed no immunoreactive cytoplasmic inclusions, excluding a diagnosis of FTLD with TDP-43 or FUS proteinopathy. Immunohistochemistry for phosphorylated tau with a monoclonal antibody AT8 and 3-repeat and 4-repeat tau with monoclonal antibodies revealed no tau pathology, excluding a diagnosis for FTLD with tauopathy. Immunohistochemistry for p62 revealed appearance of immunoreactive inclusions noted in the middle frontal and middle temporal gyri, hippocampus, and basal ganglia, the findings most likely due to the presence of Lewy body pathology. Finally, there was no pathological evidence of hippocampal sclerosis. For assessment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathological changes, Bielschowsky silver impregnation and amyloid-β immunohistochemistry were performed. AD neuropathological changes according to the revised NIA-AA guidelines5 generated an ABC score of A = 1, B = 0, and C = 1, indicating low AD neuropathological changes (ADNC). The severity of arteriolosclerosis and cerebral amyloid angiopathy was mild.

Neuropathology report on proband’s father

The proband’s father was also a part of the study, and the autopsy report was available. The macroscopic description reported a brain weight of 1100 g, with severe focal atrophy of the frontotemporal lobes and severe ventricle dilation. Microscopic examination revealed severe neuronal loss of the corticies of the frontal lobe and the middle and inferior gyri of the temporal lobe. On HE-stained sections, “Pick”-like intracytoplasmic inclusions were observed; however, the inclusions appeared atypical and were reported to be larger than typical Pick bodies more fibrillary, and eosinophilic. The pathological report also documents severe degeneration of the substantia nigra, the locus coeruleus, and the dorsal nucleus of vagal nerve, an atypical feature for Pick’s disease. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques were undetectable by modified Bielschowsky impregnation and thioflavin-S staining, respectively. At the time, immunohistochemistry staining for paired helical filament (PHF)-tau and ubiquitin was not available for review, and any anti-a-synuclein antibody was not yet commercially available. Although there was documentation of atypical features, based on the pattern of frontotemporal lobar atrophy and the presence of “Pick-like” inclusions, a pathological diagnosis of “Pick’s disease” was suggested.

GENETIC PEDIGREE REPORT

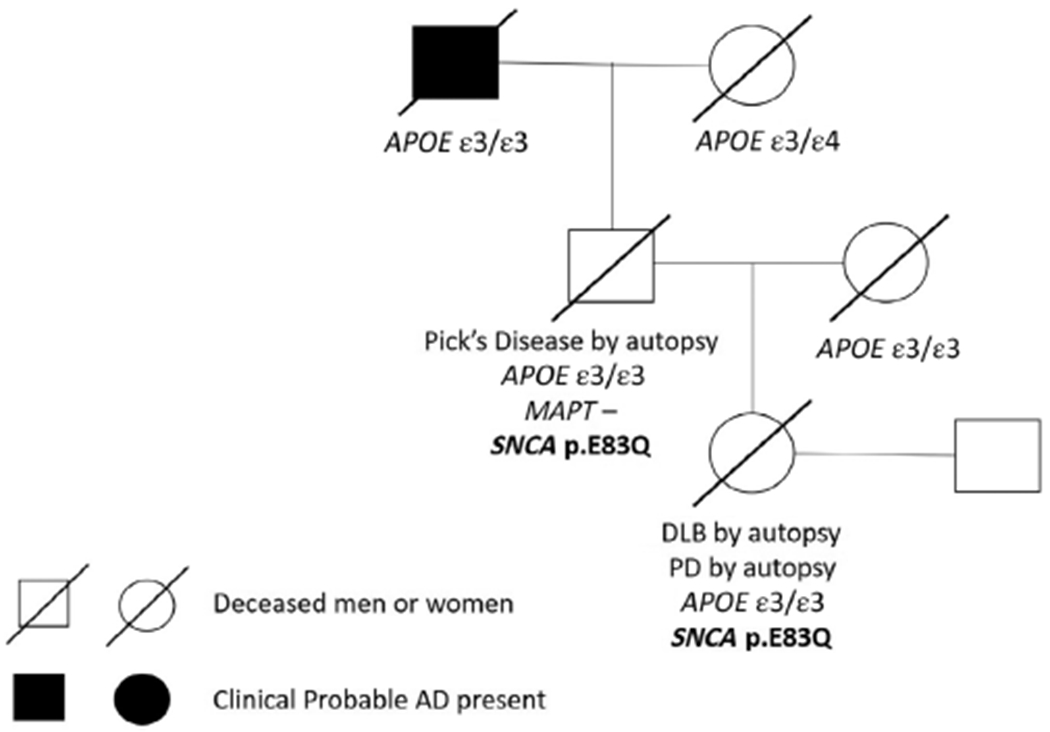

Genotyping of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene (APOE) was conducted (Fig. 3). From the genetic pedigree report, the proband, the proband’s father, and the proband’s paternal grandfather all had an APOE ε3/ε3 genotype. Sequencing of exons 1–13 of the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene (MAPT) was also conducted on the proband’s father; however, no MAPT mutations were detected. The proband’s paternal grandmother had an APOE ε3/ε4 genotype and was pathologically diagnosed as having AD.

Fig 3.

Genetic pedigree report. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APOE, the apolipoprotein E gene; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; MAPT, the microtubule-associated protein tau gene; PD, Parkinson’s disease; SNCA, the α-synuclein gene.

In addition, whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed (Fig. 3) using DNA extracted from blood from the proband and the proband’s father. Library preparation was performed using an Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon v7 capture kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Paired-end 150 base pair WES was performed using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The data were annotated with Annovar.6 We identified a novel mutation in exon 4 of SNCA, as p.E83Q. This variant is predicted to be pathogenic by a variety of functional prediction programs, including SIFT,7 PolyPhen,8 LRT,9 MutationTaster,10 FATHMM,11 MetaSVM,12 and MetaLR,13 and has a CADD-phred14 score of 25.7, indicating a high likelihood that the mutation is a functionally deleterious coding change (for full annotation, see Supplementary Table 1). Both the proband and her father were heterozygous for this novel mutation.

DISCUSSION

Here we present clinical, pathological, and genetic information from an autopsied case. The proband was confirmed to have a novel p.E83Q mutation in SNCA, and presented with aphasic clinical features and a severe atypical frontotemporal atrophy pattern with widespread neocortical Lewy body pathology. Lewy body and neurite pathology in the temporal lobe, including the amygdala, anterior temporal pole, and middle temporal gyrus, was striking and severe, and the pathological evidence for various clinical symptoms in this case was obtained by autopsy. The role of the temporal lobe, in particular the anterior portion, is thought to be critical for semantic memory, language neural networks, and social and emotional processing.15,16 In MRI studies, patients with a clinical diagnosis of DLB present with some degree of atrophy in both the parietal and frontal lobes; however, compared to those with clinical dementia of AD type, they consistently demonstrated less global atrophy with a relatively preserved medial temporal lobe.17 In clinicopathological studies, two case reports documented frontotemporal lobar atrophy associated with Lewy body pathology in patients presenting with aphasic clinical features.18,19 Atypical cases of multiple system atrophy (MSA) with severe frontotemporal lobar atrophy have also been reported.20 In the current case, a large number of neuronal inclusions diffusely throughout the neocortex, in the absence of a significant number of glial inclusions, fits the criteria of DLB rather than MSA. Overall, this case highlights that accumulation of Lewy body pathology, even in the absence of AD pathology, can severely affect medial temporal lobe degeneration, sparing hippocampal regions.

There are many environmental, genetic, and epigenetic factors that impact the course and clinical presentation of both early-onset and late-onset dementias. WES identified a missense mutation in SNCA, resulting in a coding change in exon 4, p.E83Q, in both the proband and the proband’s father. This finding is novel as it has not been previously reported in large genomic databases, and meets the criteria for inheritance and pathogenicity. Pathogenic mutations in SNCA are rare, and can result in a wide phenotypic spectrum, including PD, PDD, DLB, MSA, and even FTD. Early-onset parkinsonism, and, more importantly, those cases with pure Lewy body pathology, show a higher frequency of genetic mutations in SNCA associated with cognitive impairment.4,21 The autopsy report for the proband’s father showed a pathological diagnosis of “Pick’s disease,” based on the brain atrophy pattern and the presence of “Pick’s like,” inclusions by HE staining. However, atypical features were documented in the report, and an antibody panel for tau or α-synuclein immunohistochemistry was unavailable. The finding that the SNCA p. E83Q mutation was also present in the proband’s father, complemented by the fact that MAPT mutations, commonly identified in those with Pick’s disease, were undetectable, lends further validation that the proband’s father had an α-synucleinopathy, rather than Pick’s disease.

Differentiating between dementia subtypes clinically presents considerable challenges; on one end of the spectrum, aggregation of the same misfolded proteins (e.g. abnormally phosphorylated tau) can occur across different clinical diagnoses, while on the other, similar clinical phenotypes, non-amnestic dementia can arise due to different misfolded proteins. Furthermore, clinical phenotypic heterogeneity can pose as a diagnostic challenge for those with early-onset dementia, which manifests prior to the age of 65 years.22 Parkinsonism is a core feature for a clinical diagnosis of DLB, and is correlated with α-synuclein deposition in the brainstem nuclei, and the peripheral nervous system. However, parkinsonism features are not limited to α-synucleinopathies, and have been described in other degenerative disorders, including autosomal dominant AD, tauopathies, and some forms of FTD. Parkinsonism features can be seen in over 25% of patients clinically diagnosed as having FTD, and can precede, coincide, or follow cognitive impairment.23 Although this case had one core feature, parkinsonism changes, which could arouse clinical suspicion of DLB retrospectively, other core central features, including repeated visual hallucinations, and REM disorders, in the setting of severe and “pure” DLB were not reported. Indeed, this could be due to limited clinical information being available. However, clinical diagnostic sensitivity for DLB is low, and even in patients with “pure” DLB, core clinical features are often absent.2 In addition to degeneration of the dopaminergic system, cholinergic denervation can occur early in the disease process in patients with DLB. In this case, the patient was maintained on a cholinesterase inhibitor, even though she was clinically diagnosed with FTD, which was an appropriate symptomatic treatment of DLB. Despite this treatment, the patient had a very rapid clinical decline. A limitation to this case is that we do not know detailed clinical social/behavioral characteristics, which would be highly informative, especially in the context of an FTD diagnosis.

Overall, this case study highlights the importance of awareness of the heterogeneity of degenerative and clinical patterns associated with Lewy body pathology, and that clinical manifestations can overlap across various neurodegenerative diseases, making diagnosis in a clinical setting complicated and challenging. In addition, we identify a novel mutation in SNCA, providing a new genetic insight into the etiology underlying DLB.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank investigators and staff at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center (RADC) and the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (NCRAD). Microarray studies were carried out at the Center for Medical Genomics at the Indiana University School of Medicine, which is partially supported by the Indiana Genomic Initiative at Indiana University (INGEN); INGEN is supported in part by the Lilly Endowment.

DISCLOSURE

JRB received funding from AbbVie, Avanir, Biogen, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Novartis, Roche, Suven Life Sciences. Funding was received from the National Institute on Aging (grant number U24AG021886).

REFERENCES

- 1.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2017; 89: 88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Kryscio RJ et al. Low sensitivity in clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol 2010; 257: 359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claassen DO, Parisi JE, Giannini C, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Josephs KA. Frontotemporal dementia mimicking dementia with Lewy bodies. Cogn Behav Neurol 2008; 21: 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meeus B, Theuns J, Van Broeckhoven C. The genetics of dementia with Lewy bodies: What are we missing? Arch Neurol 2012; 69: 1113–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2012; 8: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38: e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sim NL, Kumar P, Hu J, Henikoff S, Schneider G, Ng PC. SIFT web server: Predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40: W452–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010; 7: 248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res 2009; 19: 1553–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: Mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods 2014; 11: 361–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shihab HA, Gough J, Cooper DN et al. Predicting the functional, molecular, and phenotypic consequences of amino acid substitutions using hidden Markov models. Hum Mutat 2013; 34: 57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S, Jhong JH, Lee J, Koo JY. Meta-analytic support vector machine for integrating multiple omics data. Bio Data Min 2017; 10: 2 10.1186/s13040-017-0126-8 eCollection 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong C, Wei P, Jian X et al. Comparison and integration of deleteriousness prediction methods for non-synonymous SNVs in whole exome sequencing studies. Hum Mol Genet 2015; 24: 2125–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: Predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2019; 47: D886–D894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pobric G, Lambon Ralph MA, Jefferies E. The role of the anterior temporal lobes in the comprehension of concrete and abstract words: rTMS evidence. Cortex 2009; 45: 1104–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg PB, Nowrangi MA, Lyketsos CG. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: What might be associated brain circuits? Mol Aspects Med 2015; 43-44: 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oppedal K, Ferreira D, Cavallin L et al. A signature pattern of cortical atrophy in dementia with Lewy bodies: A study on 333 patients from the European DLB consortium. Alzheimers Dement 2019; 15: 400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Zhu MW, Arzberger T, Wang LN. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with accumulation of Argyrophilic grains and Lewy bodies: A Clinicopathological report. J Alzheimers Dis 2015; 48: 55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonner LT, Tsuang DW, Cherrier MM et al. Familial dementia with Lewy bodies with an atypical clinical presentation. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2003; 16: 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aoki N, Boyer PJ, Lund C et al. Atypical multiple system atrophy is a new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration associated with alpha-synuclein. Acta Neuropathol 2015; 130: 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs J, Nilsson C, Kachergus J et al. Phenotypic variation in a large Swedish pedigree due to SNCA duplication and triplication. Neurology 2007; 68: 916–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masellis M, Sherborn K, Neto P et al. Early-onset dementias: Diagnostic and etiological considerations. Alzheimers Res Ther 2013; 5: S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espay AJ, Spina S, Houghton DJ et al. Rapidly progressive atypical parkinsonism associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuron disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011; 82: 751–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.