Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), commonly referred to as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is currently causing a severe outbreak in the United States and the world. SARS-CoV-2 mostly causes respiratory and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.1 Clinical manifestations range from the common cold to severe disease such as bronchitis, pneumonia, SARS, multiorgan failure, and death.2

SARS-CoV-2 seems to less commonly and less severely affect children. Understanding whether children are affected differently is important for clinical and containment strategies. Also, finding the nature of immune responses in children is important given the rare but severe multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children that has been reported in about 1000 cases worldwide. This recently identified syndrome appears to be temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in children.3 In this study we describe the clinical presentations, age, sex, and GI symptoms of children with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

Search Strategy

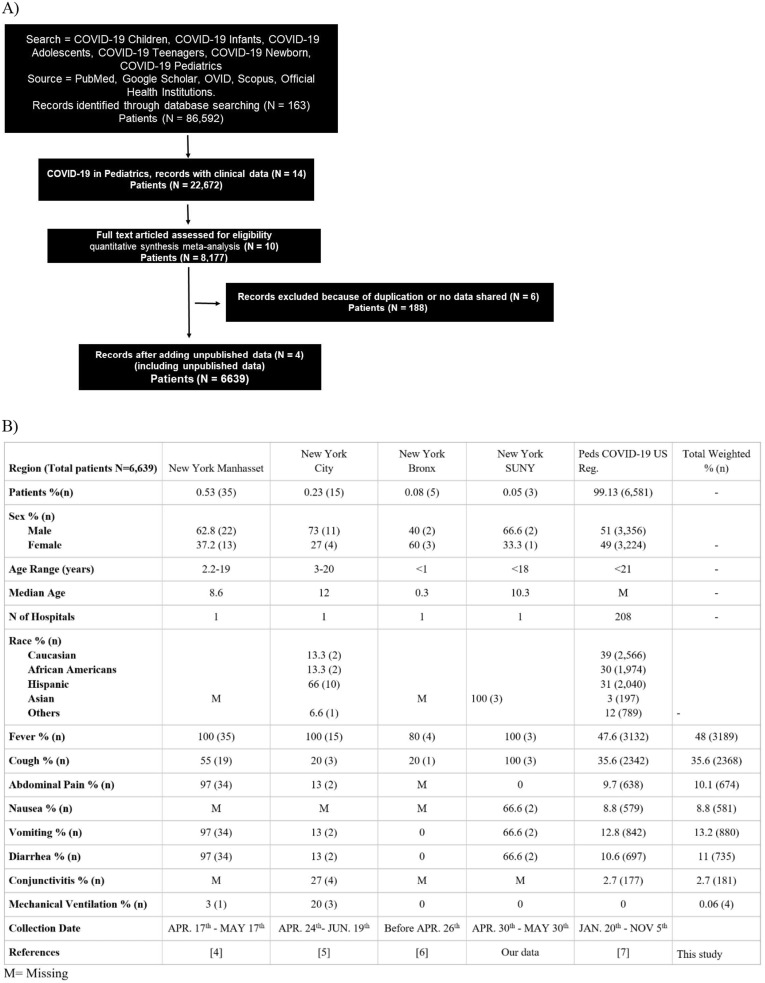

We conducted a systematic literature search of published articles using electronic databases such as PubMed, OVID, Scopus, and Google Scholar from January 20 through November 5, 2020 using the following terms: COVID-19 Children, COVID-19 Infants, COVID-19 Adolescents, COVID-19 Teenagers, COVID-19 Newborns, and COVID-19 Pediatrics. We also searched reference databases from various public health systems such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Case characteristics were described, including demographics and symptoms (Figure 1 ). We also included our limited deidentified data from Interfaith Medical Center, a tertiary hospital in Brooklyn, that is affiliated with the State University of New York.

Figure 1.

Study design and data. (A) Flowchart for study selection. (B) Demographics and clinical manifestations of COVID-19 pediatric patient data.

Statistical Analysis

Data from 6639 patients from 5 sources3, 4, 5, 6, 7 were collected. Symptoms and demographics were combined and analyzed by weighted analysis. The effect of symptoms was reported using weighted analysis where weights were related to the size of the reported study. SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for this analysis.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients

Our study consisted of 6639 patients from 212 centers in the Unites States (Figure 1). Of our 5 sources the 1 that contributed the most to patient data is the Peds COVID-19 Registry7 (208 hospitals and 6581 patients). The median age of our cohort was 14.79 years, and boys were represented at 51%. Fever was reported in 48% of patients, whereas cough was reported in 35.6% (Figure 1 B).

GI Symptoms and Distribution of Minorities

Vomiting was the predominant GI symptom in our study, reported in 13.2% of the total cohort. This was followed by abdominal pain at 10.1% and diarrhea at 11%.

Minorities were well represented in our cohort, with 1974 (29.7%) African Americans and 2040 (30.7%) Hispanics. Although no characterization of race with symptoms was available from aggregated data, the Interfaith Medical Center COVID-19 patients (all African Americans) displayed diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting in 2 of 3 African American patients (66.6%).

Discussion

In this study we describe clinical manifestations of hospitalized US children with COVID-19. The median age in our cohort was 15 years. Most children appeared to have mild disease and to recover with supportive treatment. There were slightly more boys in our cohort. However, it is not unlikely that gender has an impact on outcome.

Clinical presentations in children in our cohorts were largely nonspecific with predominance of fever and cough among both genders. With respect to GI symptoms, vomiting was the most prevalent symptom. This finding corresponds to other reports, such as from Bolia et al8 in which they report that the most prevalent GI symptom for children is vomiting.

It is worth noting, however, that in our small African American patient group from Interfaith Medical Center, diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain were represented at 66.6% (2/3 patients), pointing probably to higher GI manifestations in this minority group. Overall, Hispanic and African American children had higher cumulative rates of COVID-19–associated hospitalizations (16.4 and 10.5 per 100,000, respectively) than white children (2.1 per 100,000) and account for two-thirds of the registered deaths so far. As such, better prevention and management efforts are needed for minorities to counter risk factors and the effects of comorbidities on infection rates and disease outcome.

Given the wide variety of clinical symptoms, we recommend clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for SARS-CoV-2 infection in young infants presenting with systemic symptoms, even in the absence of fever. However, as the pandemic continues and children are unlikely to receive vaccines soon, it is critical for emergency department providers to recognize the various clinical presentations of COVID-19. A more comprehensive evaluation may be warranted in any child presenting with fever in combination with rash, conjunctivitis, and/or GI symptoms, regardless of SARS-CoV-2 exposure.

This study has the limitation of being a retrospective investigation of a relatively small patient population. Another limitation is that young children may show signs and symptoms that are not detected and reported by their guardians and physicians. As such, the appearance and frequency of new symptoms is expected to change as we get more familiar with COVID-19 in children. Also, a large portion of our data is aggregated and did not allow detailed subgroup and race-based analyses.

In conclusion, we here report that cough and fever are the primary symptoms in hospitalized pediatric COVID-19 patients in the United States. Vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea were common among these patients, with vomiting as the most prevalent GI symptom.

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Yusuf Ashktorab, (Conceptualization: Supporting; Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Validation: Supporting; Writing - original draft: Supporting). Anas Brim, (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Validation: Antonio Pizuorno, MD (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Equal; Methodology: Lead; Supervision: Supporting; Validation: Supporting; Writing - original draft: Supporting). Vijay Gayam, MD (Data curation: Equal). Sahar Nikdel, MD (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Validation: Supporting). Hassan Brim, Ph.D. (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Methodology: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Validation: Lead; Writing - original draft: Lead; Writing - review & editing: Lead).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This project was supported (in part) by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number G12MD007597.

References

- 1.Ashktorab H. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:938–940. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali I, et al. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138861. [DOI]

- 3.Sinaei R, et al. 10.1007/s12519-020-00392-y. [DOI]

- 4.Sahn B. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;72:384–387. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riollano-Cruz M. J Med Virol. 2021;93:424–433. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suwanwongse K. Arch Pediatr. 2020;27:400–401. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pediatric COVID-19 US Case Registry https://www.pedscovid19registry.com/current-data.html

- 8.Bolia R. Indian J Pediatr. 2021;88:101–102. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03481-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]