Abstract

This review showcases miRNAs contributing to the regulation of bone forming osteoblasts through their effects on the TGFβ and BMP pathways, with a focus on ligands, receptors and SMAD-mediated signaling. The goal of this work is to provide a basis for broadly understanding the contribution of miRNAs to the modulation of TGFβ and BMP signaling in the osteoblast lineage, which may provide a rationale for potential therapeutic strategies. Therefore, the search strategy for this review was restricted to validated miRNA-target interactions within the canonical TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways; miRNA-target interactions based only bioinformatics are not presented.

Specifically, this review discusses miRNAs targeting each of the TGFβ isoforms, as well as BMP2 and BMP7. Further, miRNAs targeting the signaling receptors TGFβR1 and TGFβR2, and those targeting the type 1 BMP receptors and BMPR2 are described. Lastly, miRNAs targeting the receptor SMADs, the common SMAD4 and the inhibitory SMAD7 are considered. Of these miRNAs, the miR-140 family plays a prominent role in inhibiting TGFβ signaling, targeting both ligand and receptor. Similarly, the miR-106 isoforms target both BMP2 and SMAD5 to inhibit osteoblastic differentiation. Many of the miRNAs targeting TGFβ and BMP signaling components are induced during fracture, mechanical unloading or estrogen deprivation. Localized delivery of miRNA-based therapeutics that modulate the BMP signaling pathway could promote bone formation.

Keywords: microRNA, miRNA, osteoblast, TGFβ, BMP, osteogenesis

1. Introduction

Bone is a highly dynamic mineralized tissue that plays two key anatomical roles: metabolic and mechanical [1,2]. Its metabolic role consists of the ability of bone to regulate serum electrolytes through the release of mineral from the bone matrix, and energy metabolism via release of factors, such as osteocalcin, in response to endocrine signals [1,2,3]. In its mechanical role, bone supports locomotion while protecting soft tissues and major organs [1,2,4]. Bone undergoes continuous remodeling, which is a complex process necessary for renewing bone, fracture healing and skeletal adaptation to mechanical use [2,5,6]. During normal remodeling, bone-resorptive osteoclasts, bone-forming osteoblasts, and mechano-sensing osteocytes orchestrate the remodeling process by replacing old bone with new, in order to maintain bone homeostasis and structural integrity [2,5,6]. Aside from intricate cell-to-cell communication, bone remodeling can be controlled locally by growth factors or cytokines, and systemically through calcitonin and various endocrine signals – all contributing to bone homeostasis [2,6]. Dysregulation in the remodeling process could result in an imbalance between bone resorption and formation, which impacts bone homeostasis and compromises structural integrity, highlighting the need to understand the function and regulation of bone cells and their progenitors [2,4,6].

While osteocytes play a key role in the remodeling process, bone resorption and formation are carried out by two main cell types: osteoclasts and osteoblasts, respectively [2,5,6]. Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells that originate from mononuclear cells of the hematopoietic lineage and are driven into an osteoclastic fate primarily by two cytokines, Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand (RANKL) and Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) [2,4,6]. In contrast, osteoblasts originate from multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [2,5,6]. The commitment and differentiation of MSCs into an osteoblastic lineage is tightly regulated by a number of signaling pathways including the wingless-type (Wnt), transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ), and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathways [2,4,5,6].

Osteoblasts play a pivotal role in sustaining bone microstructure and homeostasis [2,5]. Having the ability to synthesize bone matrix proteins, inadequate osteoblast number or activity is implicated in the pathophysiology of various bone disorders, including osteoporosis [2,5,6]. Clinical strategies to combat osteoporosis have often centered on impeding further bone resorption [6]. While this strategy can attenuate bone loss, it neglects to promote bone-formation, a component that is particularly problematic in the aging population [5,6]. During aging, there is a gradual decrease of osteoprogenitors, osteoblastic differentiation, and a reduction in the level of hormones such as estrogen and testosterone; this favors bone loss and increases the risk of fracture [4,7]. Fortunately, microRNA (miRNA) based therapeutics could serve to bridge the present gap in bone anabolics.

miRNAs are noncoding RNAs that function in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression [8,9,10,11,12]. miRNAs mediate post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression primarily through their direct interaction with mRNAs containing sequences complementary to the miRNA, resulting in inhibition of translation and/or enhancement of mRNA degradation [8,9,10,11,12]. These small 21–24 base RNAs are involved in many biological processes such as self-renewal, proliferation, function, and differentiation [8,10,11,12]. Recent studies have established that miRNAs can direct MSCs towards an osteoblastic lineage through modulation of TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways – both of which play important regulatory roles in bone formation, bone healing, and osteoblastogenesis [13]. The TGFβ/BMP family is complex; its ligands have both postive and negative effects on osteoblast commitment, differentiation and activity. Having a wide understanding of the signaling pathways, differentiation factors, and the mechanisms necessary for the miRNA mediated induction of multipotent cells along an osteoblastic lineage is key for the effective utilization of miRNAs as therapeutic candidates in the management of bone disorders such as osteoporosis.

Thus, this review aims to showcase miRNAs contributing to the regulation of bone forming osteoblasts through their effects on the TGFβ and BMP pathways, with a focus on ligands, receptors and SMAD-mediated signaling. While transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms regulate this pathway, it is also regulated by mechanisms that moderate ligand availability and activation. One limitation of our review is that we do not consider miRNA regulation of genes affecting the activity or availabilty of TGFβ family ligands, nor do we address miRNA regulation of non-canonical signal transduction mechanisms. However, the goal of this work is to provide a basis for broadly understanding the contribution of miRNAs to the modulation of TGFβ, BMP and activin signaling in the osteoblast lineage, and the rationale for potential therapeutic strategies. Therefore, the search strategy for this systematic review was restricted to validated miRNA targets within the canonical TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways; miRNA-target interactions based only bioinformatics will not be discussed.

To set the stage, we will briefly summarize miRNA biogenesis and function, as well as the TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways, as an introduction to the players involved.

2. miRNAs, TGFβ and BMP Basics

2.1. MicroRNAs

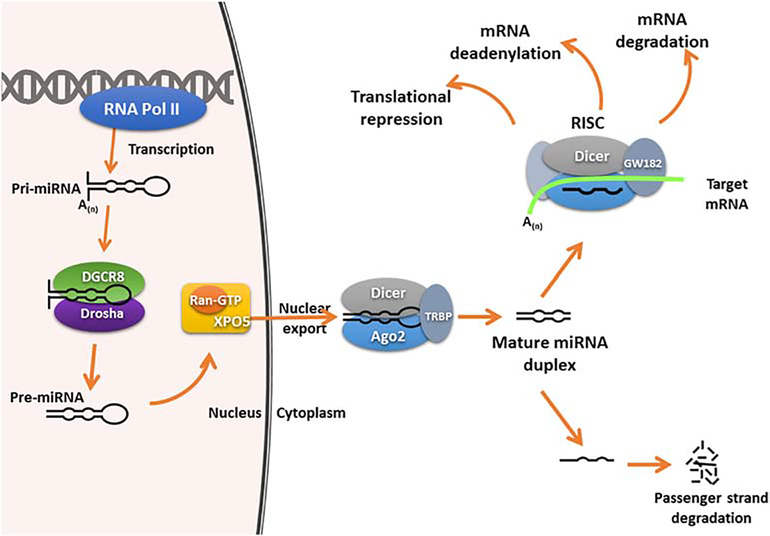

Mature miRNAs are derived from primary transcripts (pri-miRNA) synthesized mainly by RNA polymerase II (Fig. 1) [10,11,12,14,15]. While in the nucleus, the pri-miRNA undergoes the first round of cleavage by a multiprotein microprocessor complex that includes the RNase III enzyme Drosha and RNA-binding protein DGCR8 (DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8)/Pasha(Partner of Drosha) [6,9,10,11,12, 14,15,16]. This initial cleavage results in a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) which is subsequently transported to cytoplasm by Exportin-5 and Ran-GTP [5,9,12,14,15]. Once in the cytoplasm, the 70–80 nucleotide pre-miRNA is further cleaved by an RNase III enzyme, Dicer, to produce a mature miRNA duplex [9,10,11,12,14,15,16]. This miRNA duplex is then unwound, isolating the mature singled-stranded miRNA (guiding strand) from its complementary passenger strand, which is degraded [9,10,11,12,14,15,16]. The remaining single-stranded miRNA “guiding strand” is loaded onto an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) which contains Dicer, one of the Argonaute family of proteins (a central component and key player), and additional RNA-binding proteins [9,10,11,12,14,15,16]. As part of this complex, the miRNA facilitates the sequence-specific recruitment of RISC to complementary regions within the target mRNA [9,10,12,14,15]. With this sequence-specific interaction, miRNAs can regulate gene expression by destabilizing mRNAs through cleavage, or deadenylation of the target mRNAs and/or through the inhibition of protein translation [10,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Figure 1. miRNA Biogenesis.

miRNAs are transcribed by RNA-polymerase II into primary transcripts called pri-mRNA. The pri-miRNA is cleaved into pre-miRNA by Drosha and its RNA-binding partner DGCR8. The pre-miRNA is subsequently exported by Exportin-5 out of the nucleus, where it is further sliced by another RNase III enzyme, Dicer, to result in a miRNA duplex. The miRNA duplex is unwound and the mature single strand is incorporated into the RISC complex. Depending on the degree of complementary to the target mRNAs, once in the RISC complex, the mature miRNA can lead to translational repression, mRNA deadenylation, and/or mRNA degradation.

2.1. TGFβ Family Signaling

The TGFβ superfamily is composed of over 30 members including TGFβs, BMPs, growth differentiation factors (GDFs), and activins [18,19]. Members of TGFβ superfamily play key roles in the regulation of bone homeostasis [18,20,21]. Additionally, they can regulate skeletal muscle repair, cellular immune responses, and even prolong cell survival through the suppression of programmed cell death in different cell types [13,18,20,21,22]. There are 3 TGFβ isoforms in mammals (TGFβI, TGFβII, and TGFβIII), all of which are implicated in the function and metabolism of bone cells [20]. TGFβ has been documented to exert a biphasic effect on osteoblastic differentiation by promoting activation, proliferation, and early commitment of pre-osteoblasts, while impeding terminal osteoblast differentiation at later stages, especially during matrix mineralization [23,24].

BMPs are the largest subdivision of the TGFβ superfamily, and are composed of nearly 30 human proteins [19,25,26]. Due to the differences among members of the BMP subdivision, in terms of mechanics and downstream cellular effects, the term BMP is restricted to molecules that elicit activation of the canonical BMP signaling pathway, limiting the list to roughly 12 BMP ligands in humans [19]. BMPs play a key role in bone formation during development and promote the restoration of critical-size bone defects [27]. A number of BMPs display strong osteogenic capacities [28]. For example, addition of BMP2 can increase osteocalcin and bone formation, whereas a severe impairment of osteogenesis results from the loss of both BMP2 and 4 [29,30]. BMP7 is also osteogenic, mediating an increase in the expression of osteoblastic markers and mineralization in vitro [31,32,30].

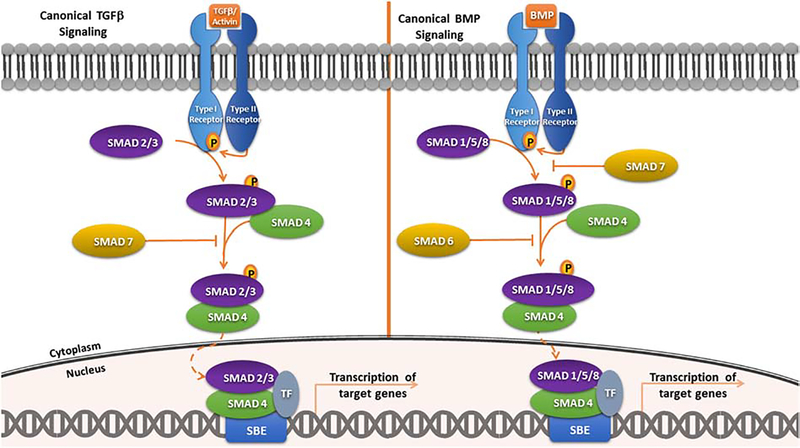

TGFβ superfamily ligands can initiate signaling cascades via both SMAD-dependent (canonical pathway; Fig. 2) and a SMAD-independent (non-canonical) pathways [5,13,33,34,35]. In canonical signaling, SMAD family members facilitate signal transduction from the ligand-activated receptors, translocating to the nucleus to regulate expression of downstream target genes [19,33,34]. The name “SMAD” references its similarity to the SMA protein of C. elegans and the MAD (Mothers Against Decapentaplegic) protein in Drosophila [33]. There are three types of SMADs in mammals: receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs), common-partner or comediator SMADs (Co-SMADs), and inhibitory SMADs (I-SMADs) [33,34,36]. R-SMADS are the five SMADs that act as substrates for the TGFβ family of receptors (SMADs 1,2,3,5, and 8) [33,34,36]. SMAD4, the only Co-SMAD, serves as a common partner for R-SMADs [33,34,36]. Lastly, SMAD6 and SMAD7 are I-SMADs, which interfere with the SMAD-receptor or SMAD-SMAD interactions and function in the negative feedback loop [33,34,36].

Figure 2. TGFβ and BMP Signaling.

Canonical signaling is initiated upon ligand binding to pairs of membrane receptor serine/threonine kinases (receptor types I and II), promoting the formation of a heterotetrameric receptor complex. Within this complex, the type 2 receptor phosphorylates and activates the type 1 receptor, which recruits and phosphorylates R-SMADs. Phosphorylated R-SMADs form heterooligomer complexes with SMAD4 for transcriptional regulation. This complex translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with different DNA-binding cofactors that confer target gene selectivity and regulation.

Activation of canonical signaling is initiated with TGFβ family ligands binding to a heterotetrameric receptor complex in the cell membrane [17,37]. This receptor complex is comprised of two type 1 receptors and two type 2 receptors, which are transmembrane dual specificity kinases [38]. Upon binding of ligand, the type 2 receptor phosphorylates and activates the type 1 receptor, which recruits and phosphorylates R-SMADs: SMAD2 and 3 for TGFβ receptors and ligands; and R-SMADs 1, 5 and 8 for BMP receptors and ligands [17,37]. This phosphorylation renders the R-SMADs active and able to form a heterooligomer complex with the ubiquitous SMAD4 [17,19,25,26,33,34,36,37]. The formation of this complex promotes nuclear translocation [17,33,34,36,37]. Once in the nucleus, the R-SMAD/SMAD4 complex binds to DNA in cooperation with other transcription factors and cofactors to induce or repress gene transcription [17,33,34,38,39].

3. miRNA Regulation of TGF Family Ligands

One manner in which miRNAs exert their regulatory role is by directly targeting the TGFβ superfamily ligands (Table 1). miR-422a, for example, was shown to target the TGFβ2 3′ UTR in human osteosarcoma cells, which display decreased levels of miR-422a and enhanced expression of TGFβ2 [40]. miR-675, encoded within the paternally imprinted lncRNA H19, is increased during osteoblastic differentiation in vitro and it directly targets human TGFβ1 [41]. Interestingly, miR-675–5p targets the TGFβ1 5’ UTR, whereas the −3p strand targets within the coding region [41]. Inhibition of miR-675 in human MSCs decreased Runx2 and osteocalcin RNAs [41]. TGFβ3, on the other hand, is targeted by miR-140–3p [42]. The expression of miR-140 is reduced in osteoblastic cells over expressing Wnt3a, suggesting a possible mechanism contributing to crosstalk between these two signaling pathways [42]. TGFβ3 is also targeted by miR-29b-3p, a pro-osteogenic miRNA that increases during osteoblastic differentiation in vitro [43].

Table 1.

miRNA Regulation of TGFβ and BMP Ligands

| miRNA | Target | Cell Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-422a | TGFβ2 | Osteosarcoma cells | 40 |

| miR-675–3p and -5p | TGFβ1 | Human mesenchymal stem cells | 41 |

| miR-140–3p | TGFβ3 | MC3T3-E1 | 42 |

| miR-29b | TGFβ3 | Human aortic valve interstitial cells | 43 |

| miR-17–5p | BMP2 | Human adipose-derived stem cells | 44 |

| miR-106a | BMP2 | Human adipose-derived stem cells | 44 |

| miR-106–5p | BMP2 | Human placental stem cells | 45 |

| miR-542–3p | BMP7 | Mouse calvarial osteoblasts | 46 |

Similar to TGFβ, BMP2 is directly targeted by miRNAs, including miR-17–5p and miR-106a, to inhibit osteogenesis [44]. In this study, overexpression of miR-17–5p and miR-106a in human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells resulted in downregulation of endogenous BMP2, suppression of osteogenesis, and a decrease in the expression of osteogenic genes such as Runx2, Osterix/SP7, alkaline phosphatase, Osteopontin, and Osteocalcin [44]. Interestingly, while overexpression of miR-17–5p and miR-106a inhibits osteogenesis, it promotes adipogenesis, causing a significant increase in Oil Red O-stained lipid droplets and adipogenic gene expression (PPARγ and C/EBPα) [44]. These data suggest a role for miRNAs in balancing commitment of a common progenitor to either an osteoblastic or adipogenic fate. Further, miR-106b-5p can also target BMP2 (human placental stem cells). In a murine model of glucocorticoid-induced osteopenia, injection of lentivirus expressing a miR-106b inhibitor attenuated bone loss and increased BMP2 mRNA in femurs. These data indicate that the targeting of BMP2 by miR-106b-5p is conserved across species, and provide proof-of-concept for targeting miR-106 to prevent bone loss [45].

BMP7, which is also an osteogenic, is targeted by miR-542–3p. In calvarial osteoblasts treated with BMP2, miR-542–3p is among the down regulated miRNAs. Osteoblasts transfected with miR-542 inhibitor had increased osteoblastic marker gene expression, and mice injected with miR-542–3p inhibitor displayed increased trabecular bone volume. Importantly, miR-542 inhibitor partially attenuated bone loss associated with ovariectomy, as well as deficits in bone mechanical properties [46]. However, whether expression of miR-542–3p, itself, was altered by ovariectomy was not examined.

4. miRNA Regulation of Signaling Receptors

Aside from targeting ligands, miRNAs can regulate osteoblastic differentiation by targeting the type I and type II receptors needed to transduce signaling from TGFβ family ligands (Table 2). For example, miR-181, which is induced by BMP2 and BMP6, was shown to target TGFβRI/ALK-5 [47]. In MC3T3 and C2C12 mouse mesenchymal cells treated with BMP2, overexpression of miR-181 decreased TGFβR1 protein levels and upregulated osteoblastic marker gene expression, as well as alkaline phosphatase activity [47]. Since TGFβ can inhibit terminal osteoblastic differentiation, miR-181-mediated downregulation of TGFβRI enhanced osteoblastic differentiation in these cell types [47]. In addition, TGFβR1 can also be targeted by miR-140–5p [48]. Interestingly, both miR-181 and miR-140–5p are induced and highly expressed during femoral fracture repair in rats. However, a correlation between their expression and TGFβ signaling was not addressed in this fracture model [49].

Table 2.

miRNA Regulation of Receptors

| miRNA | Target | Cell Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-181 | TGFβRI/ALK-5 | MC3T3 and C2C12 | 47 |

| miR-140–5p | TGFβR1 | ST2 | 48 |

| miR-17 and miR-20a | TGFβR2 | Palatal mesenchymal cells | 50 |

| miR-204–5p | TGFβR2 | Human amniotic membrane-derived mesenchymal cells | 52 |

| miR-210 | AcvR1b/ALK-4 | ST2 | 53 |

| miR-208–3p | AcvR1/ALK-2 | MC3T3-E1 | 54 |

| miR-16 | AcvR-2a | Human mesenchymal stem cells | 55 |

| miR-1187 | BMPR2 | Mouse calvarial osteoblasts | 56 |

| miR-494 | BMPR2 | C2C12 | 57 |

TGFβR2 can be targeted by miR-17 and miR-20a, which share the same seed binding region, and are expressed from the miR-17~92 cluster [50]. TGFβ signaling plays a key role in palatal mesenchyme development, and ablation of TGFβR2 in craniofacial neural crest results in cleft palate [51]. The expression of miR-17 and miR-20a are decreased from E12 to E14 in mouse embryonic development, and control of TGFβR2 levels by miRNAs may be important for normal craniofacial development [51]. Similarly, TGFβR2 can be targeted by miR-204–5p, a miRNA decreased during the osteogenic differentiation of human amniotic membrane-derived mesenchymal cells [52].

Activin receptor signaling can negatively regulate osteoblastic differentiation [58]. The type I activin receptor, AcvR1b/ALK-4 can be targeted by miR-210, to promote osteoblast differentiation [53]. Expression of miR-210 is induced by BMP4, and when overexpressed in bone marrow stromal cell line ST2, miR-210 induced expression of osteogenic gene markers genes (osterix, alkaline phosphatase, and osteocalcin) [53].

The type I receptor AcvR1/ALK2 is required for BMP7 signaling. This receptor is targeted by miR-208a-3p, a miRNA that is highly induced in mechanical unloading, a circumstance known to produce bone loss, as well as a decrease in AcvR1 expression. In mice subjected to hind limb unloading, injection with miR-208a-3p inhibitor partially rescued bone loss [54]. Further, miR-16 can negatively regulate osteoblastic differentiation by direct targeting of the type II activin receptor, AcvR2a. In this study, the authors utilized a miRNA delivery system consisting of nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) particles and collagen-nHA scaffolds to deliver antagomiR-16, which increased levels of Runx2 and Osteocalcin, as well as calcium deposition [55].

BMPR2 is targeted by several miRNAs, including mechanosensitive miR-494. This miRNA is induced in cultured mesenchymal cells subjected to simulated microgravity, as well as in bone from mice experiencing hind limb suspension. Transfection of C2C12 cells with miR-494 mimic decreased BMPR2 and inhibited BMP2-induced osteoblastic gene expression in vitro, suggesting that increased levels of miR-494 in bone as a result of unloading may contribute to decreased bone formation [57]. BMPR2 is also targeted by miR-1187. Expression of this miRNA is decreased in BMP2-treated mouse calvarial osteoblasts in vitro, suggesting a feed-forward loop to promote BMP signaling. Importantly, injection of mice with miR-1187 inhibitor decreased trabecular bone loss caused by ovariectomy [56].

5. miRNA Regulation of SMADs

miRNAs regulating the signal transducing SMADs also impact osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. For example, SMAD1 mediates signaling downstream of the BMP family ligands, and has been shown to be targeted by several miRNAs, including miR-100 [59]. Indeed, expression of miR-100 is decreased in BMP2-treated MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblastic cells. Overexpression of miR-100 attenuated BMP2-induced alkaline phosphatase activity in these cells and SMAD1 levels, suggesting that miR-100 acts as an endogenous negative regulator of differentiation [59]. The miR-30 family also targets SMAD1, blunting BMP2-induced osteoblastic differentiation [60].

As discussed earlier, TGFβ signaling can have either pro- or anti-osteogenic effects, depending on cellular context; therefore miRNAs that directly target R-SMADs 2 and 3 may induce or inhibit osteoblastogenesis. For example, miR-23b was shown to target SMAD3 in MC3T3-E1 cells. The down regulation of miR-23b in cells treated with the inflammatory stimulus lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was associated with increased SMAD3 and decreased osteoblastic differentiation [63]. In contrast, SMAD3 targeting by miR-221–5p in human bone marrow stromal cells was shown to have an inhibitory effect on osteoblastic differentiation [64]. The differential impact of SMAD3 inhibition on osteoblast differentiation in these two studies is likely related to differences in the cell systems used, as well as likely effects of the miRNA inhibitors on targets other than SMAD3.

There seem to be fewer studies on miRNAs targeting SMAD2 in the osteoblastic lineage. However, miR-10b was suggested to promote osteoblastogenesis at the expense of adipogenesis, in part by its ability to target SMAD2 [61]. miR-19–3p was shown to target SMAD2 and SMAD4 in human prostate cancer cell lines, where transfection with miR-19–3p inhibitor increased TGFβ signaling. These authors further showed that low levels of miR-19–3p are associated with bone metastases in prostate cancer biopsies, while over expression of miR-19–3p decreased tumor burden and TGFβ signaling in a mouse model of prostate cancer bone metastasis, supporting a role for TGFβ and miR-19–3p in this process [62]. Since miR-19a is also expressed in osteoblasts, the miR-19/SMAD2/4 targeting interaction validated in prostate cancer is likely relevant for the osteoblast lineage as well [73]. Similarly, miR-144–3p, which is decreased during osteoblastogenesis in vitro, regulates the differentiation and proliferation of MSCs by direct targeting of SMAD4 [65]. In this study, overexpression of miR-144–3p blunted osteogenic differentiation and inhibition of miR-144–3p reversed this process [65].

A number of studies established the suppression of osteogenic differentiation by miRNAs targeting of SMAD5. For example, miR-106b-5p and miR-17–5p, which have the same seed binding region, target SMAD5 in mouse mesenchymal cells. Expression of these miRNAs is repressed during BMP2-induced osteogenesis in both C2C12 and MC3T3-E1 cells, suggesting a feed forward loop to promote osteoblastic differentiation. Further, delivery of antagomiR for either miR-106b-5p or miR-17–5p could partially attenuate bone loss in ovariectomized mice and increased SMAD5 RNA in bone [66]. miR-155 is another miRNA that targets SMAD5 and whose expression is decreased in BMP2-treated MC3T3-E1 cells [67]. In human periodontal ligament stem cells, miR-21–5p was rapidly down regulated during osteoblastogenesis in vitro. miR-21–5p was shown to target SMAD5, contributing to the ability of this miRNA to inhibit osteoblastic differentiation. In this study, bioinformatics suggested that other members of the BMP signaling pathway could also be potential miR-21–5p targets, but only SMAD5 was validated [69]. Likewise, miR-16 was shown to negatively regulate osteoblastic differentiation by direct targeting SMAD5. In this study, a miRNA delivery system consisting of nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) particles and collagen-nHA scaffolds was used to deliver antagomiR-16, which increased the relative levels of Runx2, Osteocalcin, and calcium deposition [55]. Lastly, the expression of miR-135a decreases in C2C12 cells treated with BMP2, and this miRNA targets SMAD5, contributing to the inhibitory effect of miR-135a on osteogenesis [68].

On the other hand, targeting of inhibitory SMADs has been shown to promote osteogenic differentiation [13,70,71,72]. For example, miR-21a-5p is up regulated during osteoblastic differentiation in vitro; its targeting and down regulation of SMAD7 promotes osteogenic differentiation and increases matrix mineralization in MC3T3-E1 cells [70,71]. It is intriguing that miR-21a-5p also targets SMAD5, which transduces signaling downstream of BMPR stimulation. The ability of one miRNA to target both positive and negative regulators in the same signaling pathway is not uncommon and supports the concept that miRNAs function to fine tune the amplitude and tempo of signaling. miR-590–5p can also promote osteogenic differentiation and target SMAD7 [72]. This miRNA increases during the osteoblastic differentiation of both human and mouse MSCs. In this study, transfection of a human osteosarcoma cell line with a miR-590–5p mimic resulted in increased Runx2 protein and decreased SMAD7, as well as increased expression of osteoblast differentiation markers and calcium deposition [72]. These data suggest that miR-590–5p attenuates SMAD7-mediated inhibition of osteoblast differentiation [72].

6. Translational Implications

A thorough understanding of key molecular mechanisms regulating osteoblast differentiation and function is crucial for the development of new strategies aimed at increasing bone formation. miRNAs are estimated to post-transcriptionally regulate more than 60% of mammalian genes [74]. In the bone field, studies on miRNA-mediated gene regulation are increasing, defining their functional contribution to the mammalian skeletal system through the regulation of signaling pathways important for bone metabolism. This work highlights the potential clinical applications of miRNAs as orthobiologic agents [74]. In particular, since delivery of BMP2 is presently used to promote bone formation in vivo, miRNAs regulating the BMP signaling pathway are of interest. Therefore, studies that identify novel miRNA-target interactions and those examining in vivo models of miRNA knock down or over expression are critical for providing rationale and proof-of-concept for miRNA-based therapeutics in the management of skeletal disorders. Indeed, approximately 16 million bone fractures occur in the United States annually, of which 10–15% display either delayed healing or non-unions, which increases patient morbidity and mortality. Local delivery of miRNA-based therapeutics could help treat difficult fractures and accelerate normal physiological fracture repair [74].

While naked miRNAs are prone to degradation, a number of viral and non-viral carriers could be utilized to protect, deliver, and increase the efficiency of miRNA-based therapeutics [74,75]. An example of this strategy is the single injection of miRNA-expressing plasmids enclosed in microbubbles over fracture callus, followed by ultrasound to break the microbubbles for plasmid delivery [76]. Although viral vector-mediated delivery can result in stable and higher levels of transgene expression, their drawbacks include potential immunogenicity, toxicity, and higher production cost [74,77].

Despite the fact that non-viral vectors or small RNAs are safer and nontoxic, they have lower transfection efficiencies [74,78]. However, a number of studies describe biomaterials that can be used as miRNA-delivery-based scaffolds to increase transfection efficiencies. These materials include chitosan, calcium phosphate, peptides, nanoparticles, lipid-based or polymeric-based carriers, and polymeric hydrogels [74,79,80]. Some of materials have already shown preclinical success in treating bone defects [74].

There are a number of strategies for chemically stabilizing small RNA inhibitors (antagomiRs) or miRNA mimics (agomiRs) for delivery to cells or whole animals, and some of these modified small RNAs are in phase 1 or 2 clinical trials for diseases including fibrosis and cancer [81,82,83,84]. In regard to bone, some investigators have demonstrated the efficacy of periosteal injections of miRNA-based therapeutics at fracture sites in rodent models. These resulted in an acceleration of repair and decreased callus width, as well as an increase in osteogenic marker genes and callus bone mineral density [74,76,85]. microRNA sponges expressed in cells have also been used as competitive inhibitors of endogenous microRNAs [84,86]. When transiently transfected into cells, vectors that encode for these sponges (which contain strong promoters and multiple tandem binding sites for a miRNA of interest) can inhibit miRNA function efficiently, although their effects are not sustained [84,86]. In order to induce long-term suppression of miRNA activity, a decoy RNA system using lentiviral vectors containing RNA cassettes driven by RNA polymerase III could be utilized [84]. Through additional optimization of the decoy’s secondary structures and the miRNA-binding site, this highly potent miRNA inhibitory system could be used for well over 1 month [84].

Characterizing the function of individual miRNAs in skeletal tissue and their subsequent testing in pre-clinical models advances the utility/feasibility of miRNA-based therapeutics in the management of skeletal disorders and, in particular, bone defect repair. Presently, bone grafts are a predominant method used to treat bone defects, delayed unions or non-unions [87]. Integration of grafts with host bone can be challenging, hence improving the osteointegration of these grafts is key. To tackle this issue, bone grafting procedures have been shifting to include addition of growth factors, such as BMPs, and have exhibited good bone formation and osteointegration [87]. While use of growth factors presents a clinical improvement, further applications are limited due to concerns including high costs, supraphysiological dosing, and side effects [87]. To circumvent these issues, an understanding of miRNAs affecting the BMP signaling pathway is of considerable interest and could lead to the development of improved therapies for bone regeneration [88]. It is possible that localized delivery of miRNA-based therapeutics can modulate the BMP signaling pathway to promote bone formation and/or decrease the amount BMP used in the patient. Additionally, the synthesis of small RNAs could be less expensive than that of proteins/peptides.

Table 3.

miRNA Regulation of SMADs

| miRNA | Target | Cell Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-100 | SMAD1 | MC3T3-E1 | 59 |

| miR-30 Family | SMAD1 | MC3T3-E1 | 60 |

| miR-10b | SMAD2 | Human adipose-derived stem cells | 61 |

| miR-19a-3p | SMAD2 SMAD4 | Human prostate cancer cell lines | 62 |

| miR-23b | SMAD3 | MC3T3-E1 | 63 |

| miR-221–5p | SMAD3 | Human bone marrow stromal cells | 64 |

| miR-144–3p | SMAD4 | C3H10T1/2 | 65 |

| miR-106–5p | SMAD5 | C2C12 | 66 |

| miR-17–5p | SMAD5 | MC3T3-E1 | 66 |

| miR-155 | SMAD5 | MC3T3-E1 | 67 |

| miR-135 | SMAD5 | C2C12 | 68 |

| miR-21–5p | SMAD5 | Human periodontal ligament cells | 69 |

| miR-16 | SMAD5 | hMSCs | 55 |

| miR-21 | SMAD7 | MC3T3-E1 | 70,71 |

| miR-590–5p | SMAD7 | MG63 | 72 |

Highlights.

miRNAs can direct osteoblastogenesis through modulation of TGFβ and BMP signaling.

This review highlights miRNAs targeting TGFβ/BMP family ligands, receptors and SMADs.

Understanding miRNA-target interactions is critical for miRNA-based therapeutics.

Strategies for delivering miRNA-based therapeutics to fracture sites are discussed.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from NIAMS AR077962 (to AD) and the Center for Molecular Oncology at UConn Health. The content of the article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. JG was supported by the Connecticut Convergence Institute for Translation in Regenerative Engineering at UConn Health.

The authors thank Dr. Peter Maye and Dr. Sun-Kyeong Lee for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Long F Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;13(1):27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm3254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Florencio-Silva R, Sasso GR da S, Sasso-Cerri E, Simões MJ, Cerri PS. Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2015/421746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Karner CM, Long F. Glucose metabolism in bone. Bone. 2018;115:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bellavia D, De Luca A, Carina V, et al. Deregulated miRNAs in bone health: Epigenetic roles in osteoporosis. Bone. 2019;122:52–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Aslani S, Abhari A, Sakhinia E, Sanajou D, Rajabi H, Rahimzadeh S. Interplay between microRNAs and Wnt, transforming growth factor-β, and bone morphogenic protein signaling pathways promote osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(6):8082–8093. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19(2):179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cannarella R, Barbagallo F, Condorelli RA, Aversa A, La Vignera S, Calogero AE. Osteoporosis from an Endocrine Perspective: The Role of Hormonal Changes in the Elderly. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019;8(10):1564. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hodges WM, O’Brien F, Fulzele S, Hamrick MW. Function of microRNAs in the Osteogenic Differentiation and Therapeutic Application of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ASCs). Int J Mol Sci 2017;18(12). doi: 10.3390/ijms18122597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Faller M, Guo F. MicroRNA biogenesis: there’s more than one way to skin a cat. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2008;1779(11):663–667. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mohr A, Mott J. Overview of MicroRNA Biology. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2015;35(01):003–011. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1397344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fischer SEJ. RNA Interference and MicroRNA-Mediated Silencing. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. 2015;112(1). doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2601s112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Simonson B, Das S. MicroRNA Therapeutics: the Next Magic Bullet? Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;15(6):467–474. doi: 10.2174/1389557515666150324123208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bai Y, Liu Y, Jin S, Su K, Zhang H, Ma S. Expression of microRNA-27a in a rat model of osteonecrosis of the femoral head and its association with TGF-β/Smad7 signalling in osteoblasts. Int J Mol Med. 2019;43(2):850–860. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.4007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Michlewski G, Cáceres JF. Post-transcriptional control of miRNA biogenesis. RNA. 2019;25(1):1–16. doi: 10.1261/rna.068692.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Creugny A, Fender A, Pfeffer S. Regulation of primary microRNA processing. FEBS Lett. 2018;592(12):1980–1996. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Clayton SA, Jones SW, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Clark AR. The role of microRNAs in glucocorticoid action. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2018;293(6):1865–1874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.000366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jiang X, Wooderchak-Donahue WL, McDonald J, et al. Inactivating mutations in Drosha mediate vascular abnormalities similar to hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Sci Signal 2018;11(513):eaan6831. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aan6831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Morikawa M, Derynck R, Miyazono K. TGF-β and the TGF-β Family: Context-Dependent Roles in Cell and Tissue Physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(5). doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Thielen NGM, van der Kraan PM, van Caam APM. TGFβ/BMP Signaling Pathway in Cartilage Homeostasis. Cells. 2019;8(9):969. doi: 10.3390/cells8090969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tang SY, Alliston T. Regulation of postnatal bone homeostasis by TGFβ. Bonekey Rep. 2013;2:255. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2012.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang T, Zhang X, Bikle DD. Osteogenic Differentiation of Periosteal Cells During Fracture Healing. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(5):913–921. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang Y, Alexander PB, Wang X-F. TGF-β Family Signaling in the Control of Cell Proliferation and Survival. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9(4):a022145. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].de Gorter DJ, van Dinther M, Korchynskyi O. Biphasic Effects of Transforming Growth Factor b on Bone Morphogenetic Protein–Induced Osteoblast Differentiation. :1178–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Maeda S, Hayashi M, Komiya S, Imamura T, Miyazono K. Endogenous TGF-beta signaling suppresses maturation of osteoblastic mesenchymal cells. EMBO J. 2004;23(3):552–563. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lowery JW, Rosen V. The BMP Pathway and Its Inhibitors in the Skeleton. Physiological Reviews. 2018;98(4):2431–2452. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dituri F, Cossu C, Mancarella S, Giannelli G. The Interactivity between TGFβ and BMP Signaling in Organogenesis, Fibrosis, and Cancer. Cells. 2019;8(10):1130. doi: 10.3390/cells8101130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chen G, Deng C, Li Y-P. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(2):272–288. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.2929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huang Z, Ren P-G, Ma T, Smith RL, Goodman SB. Modulating osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells by modifying growth factor availability. Cytokine. 2010;51(3):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Noël D, Gazit D, Bouquet C, et al. Short-term BMP-2 expression is sufficient for in vivo osteochondral differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22(1):74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-1-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bandyopadhyay A, Tsuji K, Cox K, Harfe BD, Rosen V, Tabin CJ. Genetic analysis of the roles of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 in limb patterning and skeletogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(12):e216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gu K, Zhang L, Jin T, Rutherford RB. Identification of potential modifiers of Runx2/Cbfa1 activity in C2C12 cells in response to bone morphogenetic protein-7. Cells Tissues Organs (Print). 2004;176(1–3):28–40. doi: 10.1159/000075025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shen B, Wei A, Whittaker S, et al. The role of BMP-7 in chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109(2):406–416. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Massague J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes & Development. 2005;19(23):2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Macias MJ, Martin-Malpartida P, Massagué J. Structural determinants of Smad function in TGF-β signaling. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2015;40(6):296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang YE. Non-Smad Signaling Pathways of the TGF-β Family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9(2). doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wu J-W, Hu M, Chai J, et al. Crystal Structure of a Phosphorylated Smad2: Recognition of Phosphoserine by the MH2 Domain and Insights on Smad Function in TGFβ Signaling. Molecular Cell. 2001;8:1277–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Huang S, Zou C, Tang Y, et al. miR-582–3p and miR-582–5p Suppress Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Bone by Repressing TGF-β Signaling. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids. 2019;16:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Derynck R, Budi EH. Specificity, versatility and control of TGF-β family signaling. Sci Signal. 2019;12(570). doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aav5183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu M, Xiusheng H, Xiao X, Wang Y. Overexpression of miR-422a inhibits cell proliferation and invasion, and enhances chemosensitivity in osteosarcoma cells. Oncology Reports. 2016;36(6):3371–3378. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Huang Y, Zheng Y, Jia L, Li W. Long Noncoding RNA H19 Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation Via TGF-β1/Smad3/HDAC Signaling Pathway by Deriving miR-675. STEM CELLS. 2015;33(12):3481–3492. doi: 10.1002/stem.2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fushimi S, Nohno T, Nagatsuka H, Katsuyama H. Involvement of miR-140–3p in Wnt3a and TGFβ3 signaling pathways during osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. Genes to Cells. 2018;23(7):517–527. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fang M, Wang C-G, Zheng C, et al. Mir-29b promotes human aortic valve interstitial cell calcification via inhibiting TGF-β3 through activation of wnt3/β-catenin/Smad3 signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(7):5175–5185. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Li H, Li T, Wang S, et al. miR-17–5p and miR-106a are involved in the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2013;10(3):313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Liu K, Jing Y, Zhang W, et al. Silencing miR-106b accelerates osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells and rescues against glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis by targeting BMP2. Bone. 2017;97:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kureel J, Dixit M, Tyagi AM, et al. miR-542–3p suppresses osteoblast cell proliferation and differentiation, targets BMP-7 signaling and inhibits bone formation. Cell Death Dis 2014;5:e1050. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bhushan R, Grünhagen J, Becker J, Robinson PN, Ott C-E, Knaus P. miR-181a promotes osteoblastic differentiation through repression of TGF-β signaling molecules. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2013;45(3):696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang X, Chang A, Li Y, et al. miR-140–5p regulates adipocyte differentiation by targeting transforming growth factor-β signaling. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18118. doi: 10.1038/srep18118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Waki T, Lee SY, Niikura T, et al. Profiling microRNA expression during fracture healing. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:83. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0931-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li L, Shi J-Y, Zhu G-Q, Shi B. MiR-17–92 cluster regulates cell proliferation and collagen synthesis by targeting TGFB pathway in mouse palatal mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(4):1235–1244. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ito Y, Yeo JY, Chytil A, et al. Conditional inactivation of Tgfbr2 in cranial neural crest causes cleft palate and calvaria defects. Development. 2003;130(21):5269–5280. doi: 10.1242/dev.00708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Avendaño-Félix M, Fuentes-Mera L, Ramos-Payan R, et al. A Novel OsteomiRs Expression Signature for Osteoblast Differentiation of Human Amniotic Membrane-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2019/8987268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mizuno Y, Tokuzawa Y, Ninomiya Y, et al. miR-210 promotes osteoblastic differentiation through inhibition of AcvR1b. FEBS Letters. 2009;583(13):2263–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Arfat Y, Basra MAR, Shahzad M, Majeed K, Mahmood N, Munir H. miR-208a-3p Suppresses Osteoblast Differentiation and Inhibits Bone Formation by Targeting ACVR1. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids. 2018;11:323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Castaño IM, Curtin CM, Duffy GP, O’Brien FJ. Harnessing an Inhibitory Role of miR-16 in Osteogenesis by Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Advanced Scaffold-Based Bone Tissue Engineering | Tissue Engineering Part A. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2019;25(1–2). Accessed May 8, 2019. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/ten.tea.2017.0460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].John AA, Prakash R, Kureel J, Singh D. Identification of novel microRNA inhibiting actin cytoskeletal rearrangement thereby suppressing osteoblast differentiation. J Mol Med. 2018;96(5):427–444. doi: 10.1007/s00109-018-1624-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Qin W, Liu L, Wang Y, Wang Z, Yang A, Wang T. Mir-494 inhibits osteoblast differentiation by regulating BMP signaling in simulated microgravity. Endocrine. 2019;65(2):426–439. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-01952-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Goh BC, Singhal V, Herrera AJ, et al. Activin receptor type 2A (ACVR2A) functions directly in osteoblasts as a negative regulator of bone mass. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(33):13809–13822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.782128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Fu H, Pan H, Zhao B, et al. MicroRNA-100 inhibits BMP-induced osteoblast differentiation by targeting Smad1. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2016;20(18):3911–3919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wu T, Zhou H, Hong Y, Li J, Jiang X, Huang H. miR-30 family members negatively regulate osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(10):7503–7511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.292722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Li H, Fan J, Fan L, et al. MiRNA-10b Reciprocally Stimulates Osteogenesis and Inhibits Adipogenesis Partly through the TGF-β/SMAD2 Signaling Pathway. Aging Dis. 2018;9(6):1058–1073. doi: 10.14336/AD.2018.0214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wa Q, Li L, Lin H, et al. Downregulation of miR‑19a‑3p promotes invasion, migration and bone metastasis via activating TGF‑β signaling in prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(1):81–90. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Liu H, Hao W, Wang X, Su H. miR-23b targets Smad 3 and ameliorates the LPS-inhibited osteogenic differentiation in preosteoblast MC3T3-E1 cells. J Toxicol Sci. 2016;41(2):185–193. doi: 10.2131/jts.41.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Fan F-Y, Deng R, Lai S-H, et al. Inhibition of microRNA-221–5p induces osteogenic differentiation by directly targeting smad3 in myeloma bone disease mesenchymal stem cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(6):6536–6544. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Huang C, Geng J, Wei X, Zhang R, Jiang S. MiR-144–3p regulates osteogenic differentiation and proliferation of murine mesenchymal stem cells by specifically targeting Smad4. FEBS Letters. 2016;590(6):795–807. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Fang T, Wu Q, Zhou L, Mu S, Fu Q. miR-106b-5p and miR-17–5p suppress osteogenic differentiation by targeting Smad5 and inhibit bone formation. Experimental Cell Research. 2016;347(1):74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Gu Y, Ma L, Song L, Li X, Chen D, Bai X. miR-155 Inhibits Mouse Osteoblast Differentiation by Suppressing SMAD5 Expression. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2017/1893520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Li Z, Hassan MQ, Volinia S, et al. A microRNA signature for a BMP2-induced osteoblast lineage commitment program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(37):13906–13911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804438105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wei F, Yang S, Guo Q, et al. MicroRNA-21 regulates Osteogenic Differentiation of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells by targeting Smad5. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):16608. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16720-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Li H, Yang F, Wang Z, Fu Q, Liang A. MicroRNA-21 promotes osteogenic differentiation by targeting small mothers against decapentaplegic 7. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2015;12(1):1561–1567. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Arumugam B, Balagangadharan K, Selvamurugan N. Syringic acid, a phenolic acid, promotes osteoblast differentiation by stimulation of Runx2 expression and targeting of Smad7 by miR-21 in mouse mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Commun Signal. 2018;12(3):561–573. doi: 10.1007/s12079-018-0449-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Vishal M, Vimalraj S, Ajeetha R, et al. MicroRNA-590–5p Stabilizes Runx2 by Targeting Smad7 During Osteoblast Differentiation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2017;232(2):371–380. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Liu G, Chen F-L, Ji F, Fei H-D, Xie Y, Wang S-G. microRNA-19a protects osteoblasts from dexamethasone via targeting TSC1. Oncotarget. 2018;9(2):2017–2027. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hadjiargyrou M, Komatsu DE. The Therapeutic Potential of MicroRNAs as Orthobiologics for Skeletal Fractures. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2019;34(5):797–809. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Peng B, Chen Y, Leong KW. MicroRNA delivery for regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;88:108–122. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lee WY, Li N, Lin S, Wang B, Lan HY, Li G. miRNA-29b improves bone healing in mouse fracture model. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;430:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Labatut AE, Mattheolabakis G. Non-viral based miR delivery and recent developments. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018;128:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Liang D, Luu YK, Kim K, Hsiao BS, Hadjiargyrou M, Chu B. In vitro non-viral gene delivery with nanofibrous scaffolds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(19):e170. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Scimeca J-C, Verron E. The multiple therapeutic applications of miRNAs for bone regenerative medicine. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22(7):1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Wu P, Chen H, Jin R, et al. Non-viral gene delivery systems for tissue repair and regeneration. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1402-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hanna J, Hossain GS, Kocerha J. The Potential for microRNA Therapeutics and Clinical Research. Front Genet. 2019;10:478. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Bonneau E, Neveu B, Kostantin E, Tsongalis GJ, De Guire V. How close are miRNAs from clinical practice? A perspective on the diagnostic and therapeutic market. Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 2019;30(2):114–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Krützfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, et al. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with “antagomirs.” Nature. 2005;438(7068):685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature04303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Haraguchi T, Ozaki Y, Iba H. Vectors expressing efficient RNA decoys achieve the long-term suppression of specific microRNA activity in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(6):e43–e43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Tu M, Tang J, He H, Cheng P, Chen C. MiR-142–5p promotes bone repair by maintaining osteoblast activity. J Bone Miner Metab. 2017;35(3):255–264. doi: 10.1007/s00774-016-0757-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4(9):721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Wang W, Yeung KWK. Bone grafts and biomaterials substitutes for bone defect repair: A review. Bioactive Materials. 2017;2(4):224–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Sriram M, Sainitya R, Kalyanaraman V, Dhivya S, Selvamurugan N. Biomaterials mediated microRNA delivery for bone tissue engineering. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;74:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]