Abstract

Background

Reduced forward propulsion during gait, measured as the anterior component of the ground reaction force (AGRF), may contribute to slower walking speeds in older adults and gait dysfunction in individuals with neurological impairments. Trailing limb angle (TLA) is a clinically important gait parameter that is associated with AGRF generation. Real-time gait biofeedback can induce modifications in targeted gait parameters, with potential to modulate AGRF and TLA. However, the effects of real-time TLA biofeedback on gait biomechanics have not been studied thus far.

Research question

What are the effects of unilateral, real-time, audiovisual trailing limb angle biofeedback on gait biomechanics in able-bodied individuals?

Methods

Ten able-bodied adults participated in one session of treadmill-based gait analyses comprising 60-second walking trials under three conditions: no biofeedback, AGRF biofeedback, and TLA biofeedback. Biofeedback was provided unilaterally to the right leg. Dependent variables included AGRF, TLA, ankle moment, and ankle power. One-way repeated measures ANOVA with post-hoc tests were conducted to determine the effect of the biofeedback conditions on gait parameters.

Results

Compared to no biofeedback, both AGRF and TLA biofeedback induced significant increases in targeted leg AGRF without concomitant changes to the non-targeted leg AGRF. Targeted leg TLA was significantly larger during TLA biofeedback compared to AGRF biofeedback. Only AGRF biofeedback induced significant increases in ankle power; and only the TLA biofeedback condition induced increases in the non-targeted leg TLA.

Significance

Our novel findings provide support for the feasibility and promise of TLA as a gait biofeedback target. Our study demonstrates that comparable magnitudes of feedback-induced increases in AGRF in response to AGRF and TLA biofeedback may be achieved through divergent biomechanical strategies. Further investigation is needed to uncover the effects of TLA biofeedback on gait parameters in individuals with neuro-pathologies such as spinal cord injury or stroke.

Keywords: Propulsion, feedback, gait training, rehabilitation, trailing limb angle

Introduction

Real-time biofeedback is a training strategy that provides users with timely and accurate information regarding ongoing task performance.1 Biofeedback enhances motor learning by enabling users to comprehend task-related goals not explicitly perceived or understood.2 Previously, biofeedback has been used to retrain appropriate kinematics, force generation, or muscle activation patterns during functional tasks such as walking.3–5 However, to design effective and clinically-applicable gait training treatments, there is a need to determine which specific variable or parameter is most appropriate to target during gait biofeedback.

Gait speed is considered the sixth vital sign.6 Reduced gait speed is commonly observed in older adults and individuals with neurological disease (e.g. stroke), adversely affecting community participation and quality of life.7,8 With the goal of improving walking speed and function, previous gait biofeedback paradigms targeted parameters such as muscle activation, step length, and propulsive force generation.9–12 Propulsion, measured as the anteriorly-directed ground reaction forces (AGRF) during late stance, is an important biomechanical parameter that enables normal stance-to-swing transition, accelerates the center of mass forward, and promotes faster walking speed.13 In tandem with slowed walking speed, both older adults and post-stroke individuals demonstrate AGRF deficits,14,15 and an underutilized propulsive reserve.16–18 Improvements in AGRF correlate with improved walking speed,19 highlighting the importance of AGRF as a modifiable gait parameter to target during biofeedback and gait rehabilitation.

Older adults16,20 and individuals post-stroke11 have the capacity to increase propulsion in response to AGRF biofeedback. However, several biomechanical strategies may be used to modulate AGRF. Hsiao et al. previously showed that ankle plantarflexor moment and trailing limb angle (TLA) are linearly correlated with AGRF.21 At the stance-to-swing transition, a larger TLA, which measures the orientation of the leg with respect to center of mass, places the limb in a better position for AGRF generation.22 Thus, biomechanical strategies emanating from the ankle (e.g. increased plantarflexor moment) and proximally (e.g. TLA) can modulate AGRF generation.

Recent evidence suggests that modifying TLA may be a feasible and promising biomechanical strategy to increase propulsion. For example, in response to propulsive biofeedback, neurologically unimpaired older adults increased propulsion by increasing TLA, with no significant changes in ankle moment.20 Similarly, in a cross-sectional study of individuals post-stroke, generation of increased paretic propulsion was attributed to increases in TLA, with minimal contribution from ankle moment changes.17 Post-stroke intervention-induced improvements in AGRF also tended to stem from increases in TLA and not ankle moment.23 Furthermore, TLA feedback has potential for translation outside the laboratory to clinical settings because it can be measured using wearable sensors without the need for instrumented walkways. Therefore, more in-depth evaluation of TLA as a gait biofeedback target is warranted.

Before real-time gait biofeedback can be developed into an evidence-based and clinically applicable intervention, investigation of the biomechanical strategies underlying different biofeedback targets such as TLA and AGRF is a necessary prerequisite. To first assess the feasibility and biomechanical effects of modulating TLA through real-time biofeedback, here, we compared the immediate effects of a novel unilateral audiovisual TLA gait biofeedback paradigm to walking without biofeedback and with AGRF biofeedback in able-bodied individuals. We hypothesized that compared to baseline walking, and similar to AGRF biofeedback, TLA biofeedback will increase AGRF generation in the targeted leg.

Methods

Ten young able-bodied individuals (24.6±3 years, 8 females) participated in one session. Participants were excluded if they had musculoskeletal or neurological disorders affecting gait. All participants provided informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional Human Subjects Review Board.

Experimental Protocol

Reflective markers were attached to the pelvis and bilateral thigh, shank, and foot segments. Marker position data were captured using a 7-camera motion capture system (Vicon Inc., Colorado, USA). Participants walked on a dual-belt treadmill embedded with force platforms to collect ground reaction force data from each leg (Bertec Corporation, Ohio, USA). Participants held onto a front handrail for safety and were instructed to maintain a light handrail grip during all trials.

First, the self-selected walking speed for each participant was determined by incrementally increasing the treadmill speed until the participant reached what they perceived as their comfortable, natural walking speed. The self-selected speeds for study participants ranged from 0.90 to 1.10 m/s (0.96±0.70 m/s). All subsequent trials were performed at this self-selected speed. Next, participants completed three 60-second walking trials under three conditions in the following order: without biofeedback (baseline), with AGRF biofeedback, and with TLA biofeedback. These study data were collected as part of a larger study that included other testing conditions including verbal feedback and evaluation at variable gait speeds. During baseline, participants were instructed to walk normally. Right leg peak AGRF and TLA data averaged across all strides were extracted from this baseline condition. Biofeedback targets for the AGRF and TLA biofeedback trials were calculated as 25% greater than baseline right leg AGRF and TLA, respectively. Two-minute standing breaks were provided between trials.

Prior to each biofeedback trial, participants were given scripted instructions regarding the biofeedback interface, the goal of the biofeedback task, and informed that the biofeedback targets the right leg. In addition, to supplement the scripted instructions, the participants were shown a visualization depicting AGRF or TLA (using a biomechanical sketch similar to Fig. 1). For AGRF biofeedback, the scripted instructions were: “For the next walk trial, with your right leg only, I want you to push back into the ground. To help understand what I mean, I would like to show you this picture. As you see in the image, focus on the leg about to step off, notice the arrow pushing the ground backward. That is the direction of push-off I want you to focus on during the next walk. For the next minute, I want you to push back into the ground harder with your right leg only. We will show you a screen in front of the treadmill with an X on a line. The x represents how hard you are pushing back into the ground with your right leg and the ‘field goal’ to the right represents the desired target push. Push back into the ground hard enough to ensure that the X reaches the ‘field goal’ target. Each time you are successful, you will hear a beep. Not hearing a beep means that you did not push off hard enough to reach the target. You will be walking at your comfortable walking speed while lightly holding on to the handrail. Your goal is not to keep the X in the target, but to simply hit the target.” For TLA feedback, similar scripted instructions were used, except that the instructions focused on TLA instead of AGRF: “Now you will walk on the treadmill at your comfortable walking speed while lightly holding on to the handrail, but this time I want you to allow your right leg to travel farther backwards before you swing your leg, this is called trailing limb angle. As you see in this diagram (Fig. 1), the angle marked here is the TLA. I want you to walk in a way that increases this TLA by bringing your right leg farther back toward the end of your step before you lift the foot off. We will show you a screen with an X on a line. The X represents how far back your right leg is in respect to your body and the ‘field goal’ represents the desired target. Allow your right leg to travel back far enough to ensure that the X reaches the ‘field goal’ target.”

Figure 1. Schematic showing the audiovisual gait biofeedback paradigm for (A) AGRF biofeedback and (B) TLA biofeedback (adapted from Schenck and Kesar, 2016).

The cursor X depicts the current measured value of the variable being displayed. An audible beep is played whenever the cursor reaches or exceeds the specific target set for the variable being delivered.

During the biofeedback trials, a real-time audiovisual biofeedback interface displayed ongoing AGRF or TLA information for the right (targeted) leg only (Fig. 1). For AGRF biofeedback, the visual display consisted of a horizontal line with a cursor (X) that tracked the current right leg antero-posterior GRF (Fig. 1A). Increasing AGRF moved the cursor to the right towards the target, represented by a green target line with a 5-Newton error-tolerance range. For TLA biofeedback, the visual display consisted of a similar horizontal line with a cursor representing the current right leg TLA and a green target line with a 2-degree error-tolerance range (Fig. 1B). Additionally, an audible beep was generated when the cursor entered the target range. Note that the feedback target was maintained at a constant level throughout the duration of the feedback trial (25% above baseline AGRF or TLA); the biofeedback target was not modified during the gait trial in a step by step manner, nor adjusted according to ongoing changes in gait performance. Also, these study data were collected as part of a larger experimental study, limiting our ability to randomize trial order. The participants did get an opportunity to practice walking (baseline and familiarization) and walking with verbal instruction to focus on TLA or AGRF before performing the audiovisual biofeedback trials presented here. All participants appeared to be very successful in demonstrating understanding of the biofeedback task goals and making rapid adjustments to their ongoing gait performance in response to biofeedback.

Data were processed in Visual3D (C-Motion Inc., Maryland, USA). Primary dependent variables were peak AGRF and TLA of the right (targeted) leg. Secondary variables included left (non-targeted) leg peak AGRF and TLA, and targeted leg peak ankle moment and power. Peak AGRF was calculated as the maximal anteriorly directed ground reaction force during terminal stance between contralateral heel strike and ipsilateral toe-off Peak TLA was calculated as the maximum posteriorly directed angle between vertical axis of the lab and a line joining the greater trochanter and fifth metatarsal head marker. Peak ankle moment and power were defined as the peak ankle plantarflexion moment and power generation during stance phase, respectively. For each condition, data were averaged across all strides during the 60-second walking trials.

Statistical analyses

One-way repeated measures ANOVAs with post-hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons were performed to evaluate the effect of biofeedback condition (no feedback, TLA feedback, AGRF feedback) on each dependent variable. To evaluate the relative biomechanical contributions of TLA and ankle moment to peak AGRF, Pearson’s correlations were performed between feedback-induced change in peak AGRF versus feedback-induced changes in TLA and ankle moment. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (IBM, New York, USA) with alpha level set at 0.05.

Results

Targeted and non-targeted leg peak AGRF

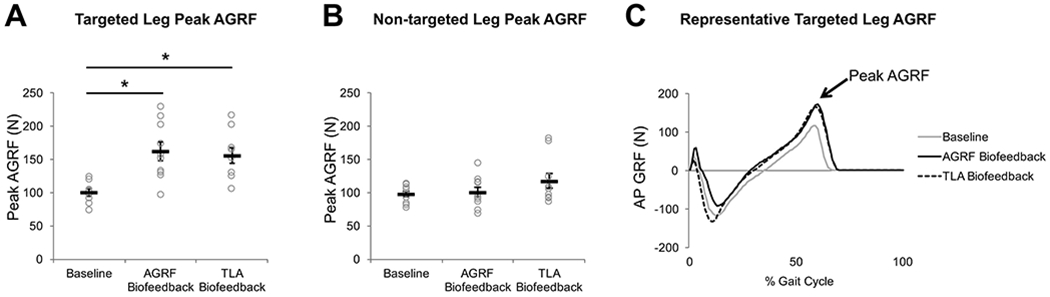

The one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback on targeted leg peak AGRF (p<0.001, F=28.498). Compared to baseline, pairwise comparisons revealed a significantly greater targeted leg AGRF during AGRF biofeedback (p=0.001) and TLA biofeedback conditions (p=0.001) (Fig. 2A). No significant differences in targeted leg AGRF were observed between AGRF biofeedback and TLA biofeedback (p=1.00) The ANOVA did not show a main effect of biofeedback on non-targeted leg AGRF (p=0.082, F=3.169) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Peak AGRF (mean ± standard error) for the (A) targeted and (B) non-targeted leg during the baseline, AGRF biofeedback, and TLA biofeedback walking conditions.

Open circles represent individual subject data. The one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback on targeted leg peak AGRF (p<0.001). The symbol * indicates pairwise comparisons that showed significant differences between conditions. Note that compared to baseline, both AGRF and TLA biofeedback significantly increased targeted leg peak AGRF. Representative data from one participant (C) show raw anteroposterior GRF data during the baseline (light gray), AGRF biofeedback (solid line), and TLA biofeedback (dashed line) conditions. The lines represent the GRF profile throughout the gait cycle averaged over all strides during the 60-sec trials.

Targeted and non-targeted leg peak TLA

The ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback condition on targeted leg peak TLA (p<0.001, F=34.427). Compared to baseline, pairwise comparisons revealed a significantly larger targeted leg peak TLA during AGRF biofeedback (p<0.001) (Fig. 3A) and TLA biofeedback (p=0.001). Significantly greater targeted leg TLA was also observed during TLA biofeedback versus AGRF biofeedback (p=0.009).

Figure 3. Peak TLA (mean ± standard error) for the (A) targeted and (B) non-targeted leg during the baseline, AGRF biofeedback, and TLA biofeedback walking conditions.

Open circles represent individual subject data. The one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback on targeted leg peak TLA (p<0.001) and on non-targeted leg peak TLA (p=0.001). The * symbol indicates pairwise comparisons that showed significant differences between conditions. While both AGRF and TLA biofeedback resulted in significantly larger targeted leg peak TLA compared to baseline, TLA biofeedback resulted in a significantly larger targeted leg peak TLA compared to AGRF biofeedback. Only TLA biofeedback resulted in significant increases to non-targeted leg peak TLA compared to baseline. Representative data from one participant (C) show raw trailing limb angle data during the baseline (light gray), AGRF biofeedback (solid line), and TLA biofeedback (dashed line) conditions. The lines represent the trailing limb angle profile throughout the gait cycle averaged over all strides during the 60-sec trial.

The ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback on non-targeted leg peak TLA (p=0.001, F=17.358). Pairwise comparisons revealed significantly greater non-targeted leg TLA during TLA biofeedback versus baseline (p=0.006) (Fig. 3B), and during TLA biofeedback versus AGRF biofeedback (p<0.001). No differences in non-targeted leg peak TLA were observed between baseline and AGRF biofeedback (p=1.00).

Targeted leg peak ankle moment

Due to errors in center of pressure measurements, data from 2 participants were excluded for the analyses of ankle moment and ankle power. The ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback on targeted leg ankle plantarflexor moment generation (N=8, p=0.001, F=10.769). Pairwise comparisons revealed a significantly greater ankle moment during AGRF biofeedback versus baseline (p=0.015) (Fig. 4A), and TLA biofeedback versus baseline (p=0.003), with no difference between AGRF biofeedback and TLA biofeedback (p=0.520).

Figure 4. Targeted leg peak ankle moment (A) and power (B) (mean ± standard error) during the baseline, AGRF biofeedback, and TLA biofeedback conditions.

Open circles represent individual subject data. The one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback on targeted leg peak ankle moment (p=0.001) and targeted leg peak ankle power (p=0.012). The * symbol indicates pairwise comparisons that showed significant differences between conditions. Note that compared to baseline, only AGRF biofeedback resulted in significant increases to targeted leg peak ankle power. Representative data from one participant show raw ankle moment data (C) and ankle power data (D) during the baseline (light gray), AGRF biofeedback (solid line), and TLA biofeedback (dashed line) conditions. The lines represent the ankle moment profile throughout the gait cycle averaged over all strides during the 60-sec trial.

Targeted leg peak ankle power

The ANOVA showed a significant main effect of biofeedback on targeted leg ankle power (N=8, p=0.012, F=6.156). Pairwise comparisons revealed significantly greater peak ankle power during AGRF biofeedback versus baseline (p=0.029) (Fig. 4B). No significant differences in ankle power were observed between baseline and TLA biofeedback (p=0.537), or AGRF biofeedback and TLA biofeedback (p=0.276).

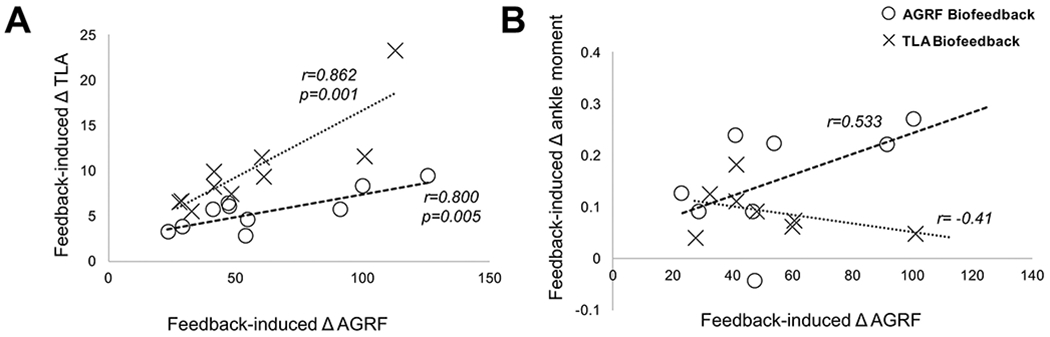

Correlations between feedback-induced change in AGRF versus TLA and ankle moment

We found a strong positive relationship between the feedback-induced change in AGRF and feedback-induced change in TLA during both AGRF biofeedback (r=0.800, p=0.005) and TLA biofeedback (r=0.862, p=0.001) (Fig. 5A). No significant correlations were detected between feedback-induced change in AGRF versus change in ankle moment. A positive (but non-significant) correlation was found between feedback-induced change in peak AGRF and change in ankle moment during AGRF biofeedback (r=0.533, p=0.173) (Fig. 5B). In contrast, a negative correlation (non-significant) was found between the feedback-induced change in peak AGRF and feedback-induced change in ankle moment during TLA biofeedback (r=−0.41, p=0.317) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Scatterplots showing associations between feedback-induced change in AGRF versus changes in TLA and ankle moment.

There is a strong positive correlation between the feedback-induced change in AGRF and feedback-induced change in TLA under both the AGRF biofeedback (open circles, r=0.800, p=0.005) and TLA biofeedback (X’s, r=0.862, p0.001) conditions. (B) No significant correlations were found between the feedback-induced change in AGRF and feedback-induced change in ankle moment under the AGRF biofeedback or TLA biofeedback conditions. However, there was a positive, albeit non-significant correlation between feedback-induced change in AGRF and ankle moment for the AGRF biofeedback condition (open circles, r=0.533, p=0.173).

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that compared to baseline, both TLA biofeedback and AGRF biofeedback induced significant increases in targeted leg peak AGRF and TLA. However, TLA biofeedback induced greater increases in TLA compared to AGRF biofeedback. Interestingly, although biofeedback was provided for a single leg, bilateral effects on TLA were observed only during TLA biofeedback. Furthermore, in contrast to TLA biofeedback, AGRF biofeedback may impose an ankle-centric strategy to increase propulsion, supported by significant increases in ankle power. Thus, manipulating the target biofeedback variable may encourage convergence to different biomechanical strategies to enhance propulsion during gait, which in turn can inform novel gait training strategies. Our findings provide support for the feasibility, biomechanical effects, and promise of TLA as a gait biofeedback target.

Both TLA and AGRF biofeedback induce comparable increases in propulsion

Consistent with previous findings,24 here, in response to unilateral AGRF biofeedback, able-bodied participants showed immediate increases in peak AGRF only in the targeted leg without concomitant changes to the non-targeted leg. Compared to baseline, TLA biofeedback also induced significant increases in peak AGRF in the targeted leg. Our findings suggest that feedback to increase TLA translates into simultaneous increases in propulsion. Previous literature proposes that a larger TLA places the leg in a better position during stance-to-swing transition, increasing propulsion during late stance.14,22,25 Although TLA biofeedback has not been tested before, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have established TLA as an important biomechanical parameter that modulates propulsion in able-bodied21 and post-stroke individuals.23,26,27 Moreover, Lewek et al. proposed that measurements of TLA can be used to accurately estimate propulsion in individuals post-stroke.28 Thus, our current demonstration of the immediate effects of TLA biofeedback on peak AGRF contribute to a compelling body of evidence supporting a strong associations between TLA and AGRF.

Here, we provided scripted, standardized instructions to the participants before each of the two biofeedback trials. The instructions focused solely on describing the feedback interface and the targeted variable (AGRF or TLA). We refrained from providing the participants suggestions or cues regarding which biomechanical strategies they could use to accomplish the feedback targets, because our goal was to evaluate strategies that an individual with an unimpaired neuromechanical locomotor system would adopt when instructed to generate unilateral increases in AGRF or TLA. Importantly, we observed no difference in the magnitude of peak AGRF during AGRF biofeedback versus TLA biofeedback. Regardless of whether the biofeedback was guiding participants to push-off harder or bring their trailing limb farther back, comparable and significant increases in AGRF were observed. Future studies will need to evaluate the effects of TLA biofeedback in older adults and individuals with neurological impairments such as stroke.

TLA biofeedback may be superior to AGRF biofeedback at increasing targeted leg TLA

During AGRF biofeedback, participants significantly increased their targeted leg TLA, suggesting that increasing TLA is a feasible biomechanical strategy to increase propulsion, and that AGRF biofeedback can concurrently increase TLA and AGRF. Notably, participants were not given instruction on specific biomechanical strategies to utilize during AGRF biofeedback, yet converged to the strategy of increasing TLA. This finding is consistent with Franz et al.20 where both young and older individuals increased TLA when instructed to increase peak propulsive force generation 20% above baseline. Individuals post-stroke also demonstrate increased TLA when forced to increase propulsion in response to a restraining force applied to their center of mass,17 or in response to AGRF biofeedback training.11

Similar to AGRF biofeedback, TLA biofeedback also induced increases in targeted leg TLA compared to baseline. Importantly, TLA biofeedback induced significantly larger increases in targeted leg TLA compared to AGRF biofeedback, suggesting the superiority of TLA biofeedback over AGRF biofeedback with respect to modulating targeted leg TLA. Given evidence relating TLA to stride length,29 we posit that compared to AGRF biofeedback, TLA biofeedback may serve as a more targeted intervention to address spatiotemporal deficits, while also having beneficial effects on propulsion.

Unlike AGRF biofeedback, unilateral TLA biofeedback induced bilateral increases in TLA

Although biofeedback was provided for a single leg, TLA biofeedback induced significant bilateral increases in TLA compared to baseline. In contrast, AGRF biofeedback did not modulate either TLA or AGRF of the non-targeted leg. Mechanisms underlying the bilateral effects of TLA feedback on TLA are uncertain. Potentially, TLA biofeedback induces a larger magnitude of increase in inter-limb TLA asymmetry compared to AGRF biofeedback, and beyond a threshold level of inter-limb TLA asymmetry, the unimpaired neuromechanical system tends to adapt by concurrently modulating kinematics of the non-targeted leg. Hemiparetic gait, commonly observed in neurological pathologies such as stroke, is characterized by inter-limb biomechanical asymmetry secondary to unilateral paresis. Whether the bilateral effects of TLA biofeedback persist in post-stroke individuals, and whether TLA feedback-induced bilateral increases prove to be undesirable, are important questions that merit investigation.

AGRF biofeedback, but not TLA biofeedback, increases ankle power generation

Despite TLA biofeedback being superior to AGRF biofeedback at increasing TLA, we found no difference in peak AGRF generation between the two biofeedback paradigms. Previous studies suggest that in addition to TLA, ankle plantarflexor moment and power play an important role in modulating populsion.21 Our results also revealed that compared to baseline, participants increased ankle power generation during AGRF biofeedback, but not during TLA biofeedback. In our study, AGRF biofeedback also induced significant increases in ankle moment, a finding that is not consistent with Browne et al.,20 who did not report an increase in ankle moment in response to AGRF biofeedback. However, one potentially important methodological difference may be that Browne et al. provided bilateral rather than unilateral AGRF feedback. Perhaps the constraint of a fixed treadmill speed imposes limitations to changing ankle kinetics when both limbs are targeted rather than a single limb.

Knee kinematics may be another consideration for the observation of significantly greater TLA during TLA feedback compared to AGRF biofeedback, without concomitant increases in AGRF. Both hip and knee extension can contribute to TLA, but other factors such as gait speed and abnormal coordination may play a role.30 The TLA and PSR likely alter the relationship between knee extension moment and propulsion. Abnormal flexor-extensor coordination, as well as premature activation of knee extensors during pre-swing can negatively impact AGRF generation.30 In individuals post-stroke, knee extension may contribute to overall leg extension (TLA), but not propulsion independently.26 Thus, the contributions of knee and hip biomechanics to TLA and pushoff warrants further investigation, especially in neurologically impaired gait.

Compared to baseline, no significant changes to peak ankle power were observed during TLA biofeedback. Thus, increases in targeted leg AGRF induced by TLA biofeedback resulted from a more optimal limb position, and not from greater ankle power generation. Our findings may have implications for individuals with pathologic gait patterns who may be unable to modulate propulsion by augmenting ankle muscle activation or power generation. For example, individuals post-stroke with severe sensorimotor impairments may possess greater capacity to modulate TLA and limited ability to modulate ankle moment and power,17,23,27 potentially making TLA biofeedback a more viable biofeedback target compared to AGRF or electromyographic biofeedback. Indeed, in previous studies, stroke survivors accomplished increases in propulsion primarily through increases in TLA rather than ankle-centric strategies.17,27 Therefore, TLA biofeedback may be more appropriate for individuals who are unable to modulate plantarflexor activity and must therefore rely on other biomechanical strategies to increase propulsion. It remains to be determined whether similar results will be observed in individuals with neurological deficits (e.g. stroke) that cause muscle paresis, and if the selection of TLA versus AGRF as biofeedback targets could be based on whether the individual has capacity to increase plantarflexor force generation.

Biofeedback-induced increases in AGRF positively correlate with TLA, but not ankle moment

Our correlation results showed that individuals who showed a large biofeedback-induced change in peak AGRF also demonstrated larger increases in targeted leg TLA, irrespective of the biofeedback variable targeted, further supporting the strong association between AGRF and TLA. In contrast, the correlation between the biofeedback-induced change in peak AGRF and ankle moment was positive for only the AGRF biofeedback condition, albeit not significant. Presumably, a subset of individuals may have utilized a strategy that promoted greater ankle plantarflexor force generation during the AGRF biofeedback trial. In contrast, the lack of a similar positive relationship between change in ankle moment and AGRF for TLA biofeedback further supports our hypothesis that increases in push-off induced by TLA feedback may not originate from an ankle-centric strategy. These correlation results, although preliminary and in a small sample, underscore the need for further larger-sample studies evaluating similar interrelationships among variables influencing propulsion, as well as biomechanical and clinical characteristics predicting normal propulsion and faster gait speeds.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations with our study. First, we did not randomize the order of walking trials. Following baseline, all participants completed the AGRF biofeedback trial, followed by TLA biofeedback. Our rationale for administering AGRF biofeedback first was to ensure that participants utilized their own biomechanical strategies to increase propulsion. In the current study, the primary target or goal of biofeedback was to increase pushoff, with both AGRF and TLA biofeedback evaluated as strategies to achieve the end goal of increasing propulsion. Therefore, we ordered the trials such as biofeedback about the primary target variable (AGRF) was provided first, and feedback about TLA, which is a second biomechanical strategy to enhance pushoff, was provided second. Had we administered TLA biofeedback before AGRF biofeedback, there remained the risk of exposing individuals to a specific biomechanical strategy to increase propulsion, which would influence their gait pattern during the AGRF biofeedback trial. Also, as previously noted, these data were collected as subset of a larger study, somewhat limiting our ability to randomize trial orders. Second, the participant’s use of the handrail may affect gait biomechanics, although we reminded participants throughout to maintain a light grip. Third, our study only explored the immediate effects of TLA biofeedback on gait biomechanics, and not locomotor learning. Fourth, the correlational analysis was preliminary and did not determine contributions of TLA and ankle moment to peak AGRF, which would be a valuable goal for future, larger-sample studies. Also, here, we used a custom, commercially available biofeedback interface to provide audiovisual feedback. Future work is needed to develop and test other methods for providing gait biofeedback outside of the laboratory using portable devices (e.g. audio only, haptic) and cues (e.g. verbal cues from a rehabilitation clinician) that can be translated and generalized to overground and clinical settings. Finally, future studies are needed to evaluate motor learning of gait patterns in response to longer training durations, as well as the effects of TLA biofeedback on gait biomechanics in populations with gait impairments.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that real-time gait biofeedback targeting TLA is a feasible paradigm to increase targeted leg propulsion and TLA. In able-bodied individuals, AGRF biofeedback induced increases in targeted leg peak AGRF through strategies comprising modification of both ankle moment, ankle power, and whole limb position. TLA biofeedback induced comparable increases in targeted leg AGRF primarily through modulation of limb angle and ankle moment. Furthermore, unlike AGRF biofeedback, unilateral TLA biofeedback induced bilateral increases in TLA. Our results regarding the immediate effects of TLA biofeedback on gait biomechanics in able-bodied individuals support the feasibility of biofeedback targeting TLA, laying foundations for future investigation of TLA biofeedback in individuals with gait impairments.

Highlights.

Real-time TLA gait biofeedback increases both TLA and propulsion in the targeted leg

Unilateral TLA biofeedback induced bilateral increases in TLA

TLA biofeedback modulated ankle biomechanics less than AGRF biofeedback

Our findings support the feasibility and promise of TLA biofeedback

Acknowledgements:

This work was funded by NIH NICHD grants R01 HD095975, K01 HD079584, and R21HD095138. The study funding agencies had no involvement in manuscript-writing or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to the current work.

References

- 1.Huang H, Wolf SL, He J. Recent developments in biofeedback for neuromotor rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2006;3:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giggins OM, Persson UM, Caulfield B. Biofeedback in rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2013;10:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreland JD, Thomson MA, Fuoco AR. Electromyographic biofeedback to improve lower extremity function after stroke: a meta-analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1998;79(2):134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards R, van den Noort JC, Dekker J, Harlaar J. Gait retraining with real-time biofeedback to reduce knee adduction moment: systematic review of effects and methods used. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2017;98(1):137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montoya R, Dupui P, Pages B, Bessou P. Step-length biofeedback device for walk rehabilitation. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing. 1994;32(4):416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritz S, Lusardi M. White paper:”walking speed: the sixth vital sign”. Journal of geriatric physical therapy. 2009;32(2):2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry J, Garrett M, Gronley JK, Mulroy SJ. Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke. 1995;26(6):982–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu HC, Chern JY, Shi HY, Chen SH, Chang JK. Physical functioning and health-related quality of life: before and after total hip replacement. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2000;16(6):285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Druzbicki M, Guzik A, Przysada G, Kwolek A, Brzozowska-Magon A. Efficacy of gait training using a treadmill with and without visual biofeedback in patients after stroke: A randomized study. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47(5):419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiello E, Gates DH, Patritti BL, et al. Visual EMG Biofeedback to Improve Ankle Function in Hemiparetic Gait. Conference proceedings : Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Annual Conference. 2005;7:7703–7706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genthe K, Schenck C, Eicholtz S, Wolf S, Kesar T. Effects of Real-time Gait Biofeedback on Paretic Propulsion and Gait Biomechanics in Individuals Post-Stroke. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2017;98(10):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Intiso D, Santilli V, Grasso MG, Rossi R, Caruso I. Rehabilitation of walking with electromyographic biofeedback in foot-drop after stroke. Stroke. 1994;25(6):1189–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelik KE, Adamczyk PG. A unified perspective on ankle push-off in human walking. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2016;219(23):3676–3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowden MG, Balasubramanian CK, Neptune RR, Kautz SA. Anterior-posterior ground reaction forces as a measure of paretic leg contribution in hemiparetic walking. Stroke. 2006;37(3):872–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franz JR, Kram R. Advanced age affects the individual leg mechanics of level, uphill, and downhill walking. Journal of biomechanics. 2013;46(3):535–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franz JR, Maletis M, Kram R. Real-time feedback enhances forward propulsion during walking in old adults. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon). 2014;29(1):68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewek MD, Raiti C, Doty A. The Presence of a Paretic Propulsion Reserve During Gait in Individuals Following Stroke. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2018;32(12):1011–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conway KA, Bissette RG, Franz JR. The functional utilization of propulsive capacity during human walking. Journal of applied biomechanics. 2018;34(6):474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowden MG, Behrman AL, Neptune RR, Gregory CM, Kautz SA. Locomotor rehabilitation of individuals with chronic stroke: difference between responders and nonresponders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(5):856–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Browne MG, Franz JR. More push from your push-off: Joint-level modifications to modulate propulsive forces in old age. PloS one. 2018;13(8):e0201407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiao H, Knarr BA, Higginson JS, Binder-Macleod SA. The relative contribution of ankle moment and trailing limb angle to propulsive force during gait. Hum Mov Sci. 2015;39:212–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tyrell CM, Roos MA, Rudolph KS, Reisman DS. Influence of systematic increases in treadmill walking speed on gait kinematics after stroke. Phys Ther.91(3):392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsiao H, Knarr BA, Higginson JS, Binder-Macleod SA. Mechanisms to increase propulsive force for individuals poststroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2015;12:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schenck C, Kesar TM. Effects of unilateral real-time biofeedback on propulsive forces during gait. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balasubramanian CK, Bowden MG, Neptune RR, Kautz SA. Relationship between step length asymmetry and walking performance in subjects with chronic hemiparesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(1):43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson CL, Cheng J, Kautz SA, Neptune RR. LEG EXTENSION IS AN IMPORTANT PREDICTOR OF PARETIC LEG PROPULSION IN HEMIPARETIC WALKING. Gait & posture. 2010;32(4):451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsiao H, Knarr BA, Pohlig RT, Higginson JS, Binder-Macleod SA. Mechanisms used to increase peak propulsive force following 12-weeks of gait training in individuals poststroke. J Biomech. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewek MD, Sawicki GS. Trailing limb angle is a surrogate for propulsive limb forces during walking post-stroke. Clinical Biomechanics. 2019;67:115–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGrath RL, Ziegler ML, Pires-Fernandes M, Knarr BA, Higginson JS, Sergi F. The effect of stride length on lower extremity joint kinetics at various gait speeds. PloS one. 2019;14(2):e0200862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roelker SA, Bowden MG, Kautz SA, Neptune RR. Paretic propulsion as a measure of walking performance and functional motor recovery post-stroke: a review. Gait & posture. 2019;68:6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]