Abstract

Current models of financial burden after cancer do not adequately define types of financial burden, moderators or causes. We propose a new theoretical model to address these gaps. This model delineates the components of financial burden as material and psychological as well as healthcare-specific (affording treatment) versus general (affording necessities). Psychological financial burden is further divided into worry about future costs and rumination about past and current financial burden. The model hypothesizes costs and employment changes as causes, and moderators include precancer socioeconomic status and post-diagnosis factors. The model outlines outcomes affected by financial burden, including depression and mortality. Theoretically derived measures of financial burden, interventions and policy changes to address the causes of financial burden in cancer are needed.

Keywords: : economic well-being, financial anxiety, financial toxicity, neoplasm, theoretical model

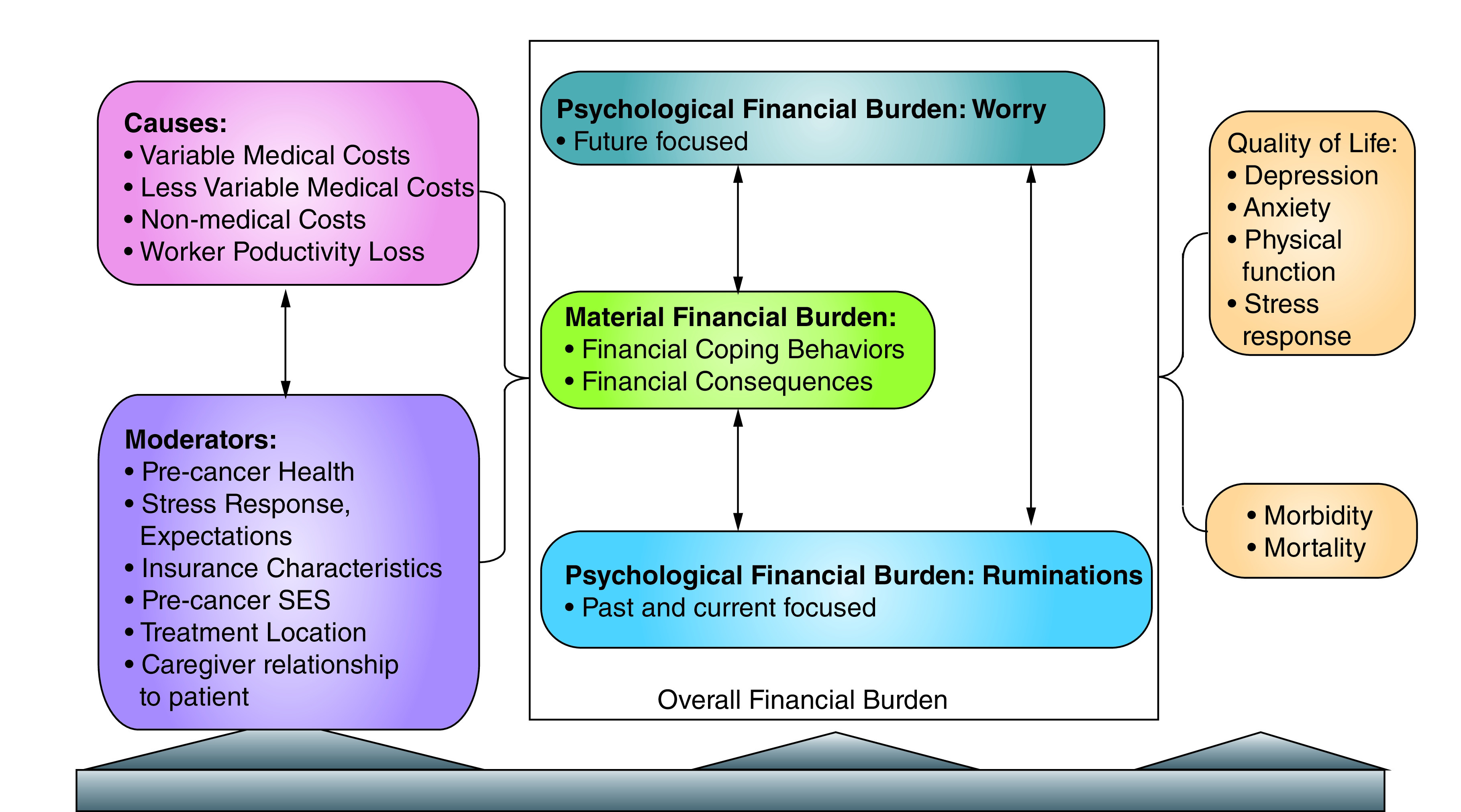

Graphical abstract

Cancer care is extremely expensive, with the total cost of treatment reaching $10,000 per month or more [1]. The high costs of cancer care impact the patient, their caregivers and families due to increased cost-sharing, the intensity and chronicity of treatment and the impact on employment and income [2]. Previous studies have reported that the prevalence of cancer-related financial burden ranges from 16 to 80% [3–9]. Financial burden increases the risk of depression, anxiety and poor quality of life (QoL) in cancer [10–17] and lowers the odds of survival [18].

Despite the high prevalence of financial burden among cancer survivors and its downstream effects on outcomes, QoL and survival, financial status is not routinely assessed in clinical practice [19], nor do evidence-based interventions exist to mitigate this burden. Patients are interested in costs early in the continuum of care but providers are reluctant to address the issue [20]. As a further barrier to evaluation and intervention, financial burden is a complex, multifaceted problem raising issues about when to screen patients, for what types of financial burden, and what to do once financial burden is discovered.

A fundamental barrier to advancing the research on financial burden is the lack of a conceptual and theoretical model of patient-level financial burden that could be used to design and test interventions and direct policies that improve outcomes for patients versus the healthcare system or society at large. While previous models have proven useful, most current models of financial burden are purely descriptive with few causal relationships delineated, despite the fact that understanding these relationships is necessary to design interventions and policy changes [21,22].

Several models of financial burden in cancer have been proposed. A model by Altice and colleagues, sometimes referred to as the Financial Hardship Framework, delineates three types of financial burden or hardship: material conditions (debt, lost income), psychological response (worry, distress) and coping behaviors (nonadherence) [21]. In other models, objective financial stress is distinguished from subjective financial strain [23,24]. Financial stress represents discrete events triggering financial burden, such as bills and transportation costs [25]. Financial strain represents the psychological response to financial burden, such as distress and worry from the Financial Hardship Framework. The model by Gordon and colleagues [22] outlined three constructs related to financial burden that overlap with the models of Francoeur [23] and Altice: objective (coping behaviors and some material conditions from Altice and colleagues), subjective (psychological response from Altice and colleagues and financial strain from Francoeur) and monetary measures (financial stress from Francoeur and some material conditions from Altice and colleagues).

The terminology and lack of specificity of the constructs is a drawback of current models. These models also do not address the issue of moderators or outcomes such as QoL or mortality. Another limitation of the Financial Hardship Framework is the way in which it defines the three types of financial hardship. Coping is centered almost entirely on medical adherence, while behaviors that could be construed as coping, such as incurring debt, are classified solely as material conditions. In Francoeur's model, the terms ‘financial stress’ and ‘financial strain’ have often been used interchangeably, and the majority of models do not distinguish between different types of psychological financial burden [23]. The lack of distinction between types of psychological responses to financial issues displayed by previous models stymies any testing of interventions, because an intervention may only affect one type of financial burden or may affect a causal mechanism associated with a different type of financial burden. Conflating the types of financial burden and not distinguishing their different causal mechanisms could lead to the conclusion that an intervention was ineffective when in reality the wrong type of financial burden was assessed relative to the target of the intervention.

An expanded model of financial burden

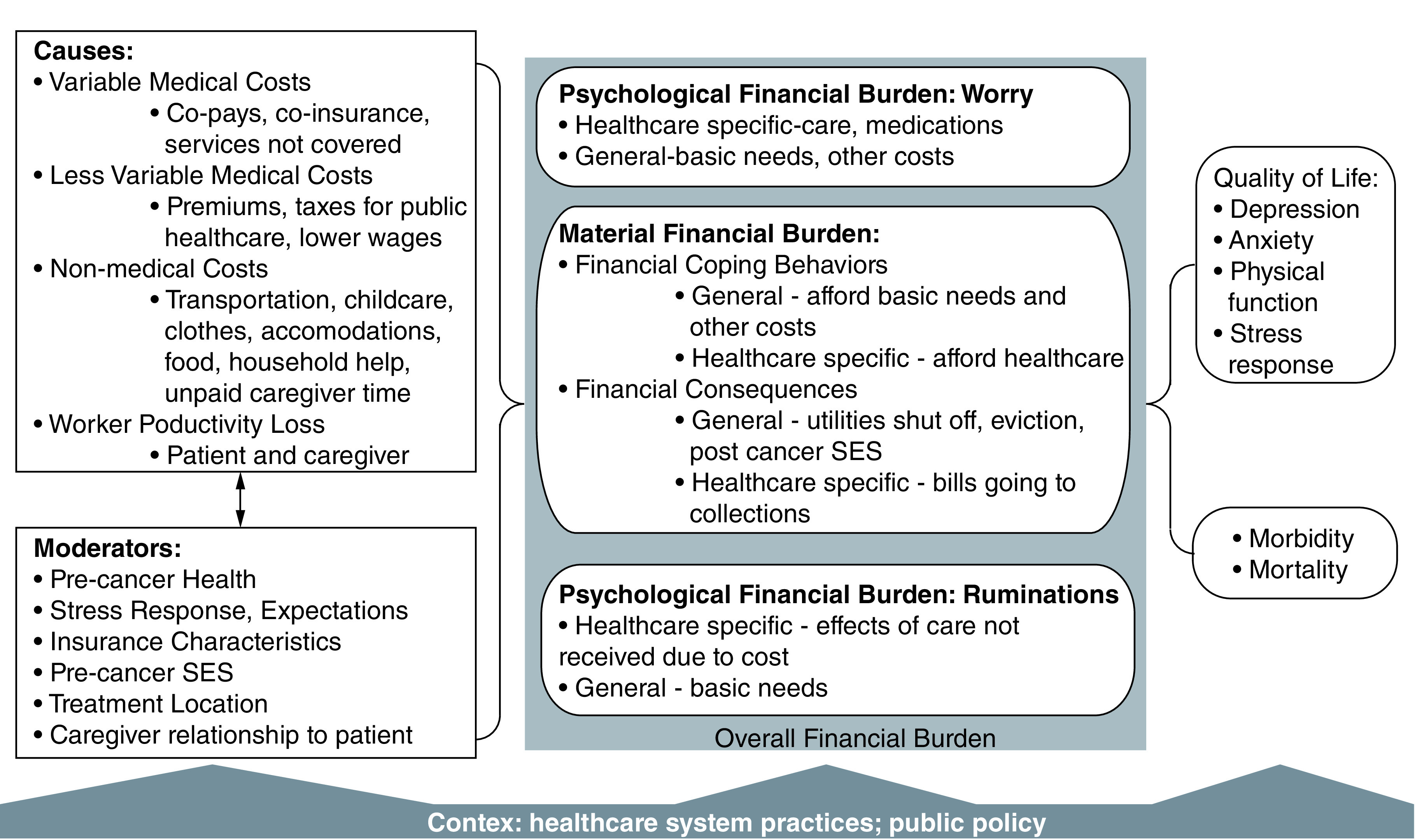

This commentary proposes a theoretical model of financial burden after cancer diagnosis (see Figure 1 for the model, Table 1 for definitions) to fill gaps in previous models and to help guide future research and clinical care. The model is based on current models and empirical literature as well as psychological theories of stress, depression and anxiety [21–23,26–30] and the Second Panel of Cost–Effectiveness [31,32]. Previous models are extended by elaborating relevant, measurable components of financial burden, hypothesizing temporal and causal relationships and incorporating moderators and outcomes that can be tested empirically in longitudinal or intervention research.

Figure 1. . Model of financial burden after cancer diagnosis.

SES: Socioeconomic status.

Table 1. . Definitions of financial burden, causes and moderators.

| Term | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Material | |

| Material financial burden | Material or tangible consequences of the costs of cancer and its treatments. |

| Healthcare-specific financial coping behaviors | Specific actions patients and their families take to afford care, such as starting a crowdfunding campaign or rationing medication. Referred to as material conditions, coping behaviors and objective by previous models. |

| General financial coping behaviors | Specific actions patients and their families take to afford basic needs that are harder to afford due to the costs of care. Examples include reducing spending on luxuries, working multiple jobs due to the high cost of living, or moving to a cheaper apartment. Referred to as material conditions, coping behaviors and objective by previous models. |

| Healthcare-specific financial consequences | Events that result from patients’ inability to cope with the causes of financial burden. Examples include being sued by a healthcare provider for unpaid bills, healthcare bills going to collections and liens being placed on property by healthcare organizations. |

| General financial consequences | Events in a patient’s general financial life that result from inability to pay for care. Examples include eviction, utilities being shut off and increased food insecurity. |

| Psychological | |

| Psychological financial burden | Negative emotions and thoughts associated with one’s financial situation that result from causes or material financial burden. Referred to as psychological response, subjective and financial strain by previous models. |

| Worry about affording healthcare | Worry and anxiety about affording future healthcare services, medications and devices. |

| General financial anxiety | Worry and anxiety about one’s overall financial burden, including the cost of necessities like food and shelter. |

| Depression and rumination over material financial burden, healthcare-specific | Depressive symptoms and negative thinking about past or current material financial burden that resulted from the cancer and treatment. |

| Depression and rumination over material financial burden, general | Depressive symptoms and negative thinking about past or current material financial burden related to meeting basic needs. |

| Causes | Discrete events that lead to financial burden; can also be called financial shocks. Referred to as financial stress, material conditions and monetary measures by previous models. |

| Medical costs | Causes of financial burden that are costs directly resulting from medical care such as co-pays, co-insurance and costs of services not covered by insurance. Costs can be variable (co-pays) or less variable (premiums). |

| Indirect (nonmedical costs) | Causes of financial burden that are costs resulting from the cancer but not directly related to health services costs. Examples include transportation costs, food costs and paying for childcare. |

| Moderators | Factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of causes affecting financial burden. Can be at the individual, caregiver, organizational or policy level and can pre-date the cancer diagnosis. Examples include treatment location, bill collection practices and disability accommodation policies. |

The model defines financial burden as any negative effect of the cancer on a patient's finances [33] or solutions to the costs of care [21,22]. Financial burden is represented in the model along two dimensions: material versus psychological, and general (basic needs, other costs) versus healthcare-specific. As conflating different types of psychological financial burden can lead to prematurely discarding an intervention, the model distinguishes worry about affording future care or needs from financial rumination about past or current material financial burden.

Causes of financial burden

The model distinguishes causes of financial burden from precancer factors that buffer against or increase the risk of financial burden, such as health insurance coverage [34]. Causes of financial burden are discrete events that lead to financial burden and primarily are costs associated with care, such as out-of-pocket costs for diagnosis and treatment [35–38], but can also include loss of income [39]. The model distinguishes medical costs (out-of-pocket costs such as co-pays) from nonmedical costs, often referred to as indirect costs [40,41]. Medical costs can be variable (e.g., co-pays or co-insurance) or less variable (e.g., insurance premiums) [42]. Indirect, nonmedical costs include transportation to appointments and help with household tasks when cancer care prevents patients from performing their usual work. Another important individual-level stressor and cause is employment changes.

Within causes, all costs – medical and nonmedical – are hypothesized to be stressors that lead to both material and psychological financial burden, although variable costs might be more likely to provoke financial worry due to the uncertainty. Empirical studies have supported the association of costs with various forms of financial burden [17,43]. Previous research has established that employment changes for the patient and caregiver are common after cancer [44].

Causes of financial burden are separated from financial burden itself for several reasons. First, this approach places the patient in a more active role in which the way they respond to costs determines the impact on outcomes, rather than a passive role in which financial burden is something that is done to the patient. Second, this allows focus on the root cause of financial burden in cancer, namely that the care is too costly and that patients often lose some ability to work due to an environment that will not accommodate them.

Moderators of financial burden

We posit that certain individual and organizational or policy-level factors (clinic, healthcare system, family leave and disability accommodation laws) moderate the likelihood of financial burden when experiencing a cause or triggering event. Race and ethnicity are likely moderators [4,45]. Indirect, nonmedical costs are likely increased with more rural location or living further from the primary cancer treatment location [46]. Patient characteristics that might moderate the association of causes with financial burden include self-efficacy [27,47] and cost expectations [48]. The relationship between caregiver and patient may also moderate the effects of financial burden on outcomes; caregivers who are more financially tied to the patient (spouse) may experience more burden than other caregivers (adult child, sibling) [41].

Precancer factors such as socioeconomic status and health can also moderate the association between cause and financial burden. It is important to distinguish two aspects of socioeconomic status: wealth and income. ‘Income’ refers to regular amounts of money a person is paid, which may be in jeopardy after cancer diagnosis for both the patient and their family members, whereas ‘wealth’ is money and other forms of capital, including extended family resources, already in hand. Because income is often dependent on employment and is therefore more likely to decrease after diagnosis for both the patient and their family members, wealth may provide more protection against financial burden because it is not affected by the patient’s or caregiver’s continued employment. A patient’s precancer health (e.g., the existence of comorbidities) likely also increases the risk of financial burden, possibly through higher precancer health costs [49].

Material financial burden

Material financial burden is divided into financial consequences and financial coping behaviors; it is important to distinguish these from causes such as costs of care and reduced or lost income. Financial consequences are specific events that occur because of inability to pay for care or basic needs. Examples of healthcare-specific financial consequences include bills going to collections, having wages garnished or having liens placed on one’s assets due to unpaid bills. Examples of general financial consequences include eviction, credit ratings decreasing and a change in the patient’s post-cancer socioeconomic status compared with precancer levels.

Financial coping behaviors

Financial coping behaviors are specific actions taken to maintain healthcare and afford basic needs. These healthcare-specific coping behaviors include setting up a payment plan for medical bills and extend to filing for bankruptcy due to medical debt. Cost-related nonadherence and healthcare use are healthcare-specific forms of financial coping; patients may self-ration their care because of the costs. Employment changes may be either a cause of financial burden when a patient or caregiver must decrease their hours, or a financial coping behavior if they increase hours or work another job to cover the costs of care and basic needs. General financial coping behaviors include applying for basic needs assistance and moving to cheaper housing. Previous models did not distinguish types of financial coping behaviors [30] but research has shown each type of coping behavior is differentially related to outcomes [50]. Debt may be classified as either financial coping (if the patient actively incurred the debt) or financial consequences (if the bill is ignored and goes into collections).

Once causes trigger financial coping, these behaviors can then moderate whether the patient experiences financial consequences and further psychological financial burden. For example, a patient may engage in enough financial coping to prevent most financial consequences but still experience financial worry and rumination due to the extent of the coping needed. System or organizational-level factors may moderate material financial burden in the context of high costs. As an example, patients of clinics that provide financial assistance and explain the costs of care might be less likely to engage in unnecessary financial coping behaviors. As another example, a bill might be sent to collections because the cost is too high to pay and the healthcare system has a policy of sending the bill to collections rather than providing payment plans. In this case, the patient can engage in as much coping as possible, but the bill still goes to collections.

Psychological financial burden

Psychological financial burden can be a constellation of negative emotions and cognitions, often resulting from causes and material financial burden, but can also occur as anxiety about anticipated future material financial burden and causes. A similar distinction has been drawn between rumination and worry in psychopathology [26]. Worry (future-focused cognition/thoughts) tends to be associated with anxiety, while rumination (past-focused cognition/thoughts) tends to be associated with depression [51]. The model therefore distinguishes financial worry and anxiety from financial rumination and depression; the two states are collectively referred to as psychological financial burden. Psychological financial burden can also be divided into general (basic needs, other life goals) and healthcare-specific.

As noted above, the model is unique in distinguishing between material and psychological financial burden and in distinguishing subtypes of psychological financial burden. Studies that directly compared material financial burden and psychological financial burden showed that these two constructs are not synonymous [3,4,7,52], although previous studies frequently conflate them [8]. Different types of psychological financial burden may have different consequences for a patient and may respond to different interventions. For example, a person who is worried about affording the cost of a doctor’s visit to address chemotherapy-related nausea may be less likely to make an appointment regardless of objective markers of financial health.

The lack of distinction between worry-based psychological financial burden and rumination-based psychological financial burden in previous models is problematic because worry and rumination are associated with different outcomes in the psychopathology literature [53–58]. For this reason, the model distinguishes rumination and depressive symptoms from financial worry and anxiety.

The model further posits worry about affording healthcare as a predictor of material financial burden, because worry is often the result of anticipating future negative events [26] and could therefore be a prodromal indicator of material financial burden yet to happen. Although material financial burden likely also increases future worry about affording care and basic needs, in the initial stages after diagnosis worry may predict later material burden because insufficient time has passed for these events to occur. Worry about affording healthcare may also increase future financial coping behaviors, such as starting a crowdfunding campaign. As shown by decades of psychological research in both the general and clinical populations, the typical response to anxiety and worry is avoidance [26], including for financial worry and anxiety [59]. Cancer patients who are worried about affording care or basic needs may engage in healthcare-specific financial coping in the form of cost-related nonadherence and reduced healthcare use as avoidance [9,60,61]. Patients with high worry about affording care may also conserve financial resources; the threat of a loss of resources may be even more motivating than the loss itself [28].

For psychological financial burden the distinction between general and healthcare-specific burdens may be crucial for determining whether interventions work and for screening patients. Research on other types of anxiety, such as dental anxiety and pregnancy anxiety, has shown that general anxiety and worry are not predictive of behavior and outcomes, but anxiety and worry specific to those health concerns are predictive [62,63]. Therefore the model distinguishes worry about affording healthcare from general financial worry or anxiety, as well as separating financial rumination and depression for general versus healthcare-specific reasons.

Levels of the model

In the model, financial burden and outcomes affected by it, including QoL and survival, are conceptualized as being at the patient and caregiver level. These are consistent with the self and interpersonal levels of the socioecological model [64]. Causes can be at multiple levels, including the patient and caregiver levels. Self-efficacy for understanding health insurance and employment changes would be at the individual level for the patient and the caregiver. Health insurance and disability accommodation policies would be at the societal level. Clinic differences on sending bills to collections, explaining costs of care, or providing short-term financial assistance or support in finding pharmaceutical programs for reduced medication costs would be another level of factors affecting the risk of patient and caregiver financial burden, and lies between the patient and societal levels. Although this model centers the patient, it is important to also acknowledge the broader factors affecting financial burden, particularly the way in which these systemic factors can cause or moderate later financial burden.

Outcomes associated with financial burden

Although financial health is an important aspect of overall QoL, the model further hypothesizes that financial factors can predict other outcomes in cancer survivors. Based on cross-sectional [10,12–15] and longitudinal research [65], the model includes the relationship of financial burden to both mental and physical QoL as well as a prolonged stress response. The model also includes a hypothesized association of material and psychological financial burden with mortality and morbidity. This is supported by a study linking bankruptcy with a higher risk of early death [18]. Studies linking cancer treatment nonadherence with earlier mortality also support this association [66]. Based on associations between financial worry and nonadherence to medications or avoidance of healthcare visits, the link is extended from worry to morbidity and earlier mortality.

Measures of financial burden

Although several measures of financial burden and associated causes and outcomes exist, development of additional measures is required for several parts of the model. For causes of financial burden, costs have traditionally been measured using insurance claims databases [67,68], cost diaries [69] or retrospective items [70,71]. These measures have clear uses, but claims databases can only estimate out-of-pocket costs, diaries can be burdensome, and retrospective measures may have high recall bias. Most moderators – such as rurality [72], income, race/ethnicity, self-efficacy for using health insurance [73] and comorbidity [74] – have standard measures. A popular measure in the financial burden literature is a ratio of medical costs over income, with medical costs of either 10 or 20% of income indicating high financial burden [21]. While it is understandable that some might use this ratio, it might conflate a moderator and a cause and serve more as a proxy than as a direct measure of financial burden. The ‘percentage of income’ measure may not account for nonlinear relationships between income and medical costs. For example, people in the lowest income quartile would likely find a 10% measure more burdensome than people in the highest income quartile.

Patient-reported measures of financial burden, including general financial burden and financial anxiety, have been developed but tend to be for the general population or lack specificity for the different types of financial burden [75–77]. These measures do not assess healthcare-specific financial burden and have not been validated in cancer patients. The Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity is a measure of financial burden validated specifically for cancer patients [8]. However, its main drawback is that it contains both general and healthcare-specific items and both material and psychological financial burden items. Measures for healthcare-specific psychological financial burden are also needed, because current measures are either a subscale of larger measures [78] or are not validated in cancer [79,80]. Measures of financial coping and consequences are needed because no comprehensive measure of these constructs exists, particularly one distinguishing healthcare-specific from general financial burden [70,81]. One exception is for cost-related nonadherence and healthcare utilization [3,82].

Many of the outcomes in the model already have well-validated measures. Numerous psychometrically sound measures of QoL are available. Morbidity and mortality are typically measured using electronic health records or administrative record data.

Recommendations for future research

Improving measurement of financial burden, as reflected in this model, is a first step in confirming the hypothesized relationships between each type of financial burden and outcomes. Future measure development should also confirm whether the distinction of general versus healthcare-specific financial coping is correct or whether other models apply. However, measures need to be developed with practical clinical application in mind. As most studies have been cross-sectional, future studies on financial burden in cancer need to be longitudinal, particularly to further confirm the predictions of the model.

In addition to assessing patient-level financial burden, future research is needed to identify which interventions affect which types of financial burden. The Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education has a continuum of financial interventions that includes financial education, counseling and coaching [83]. Other interventions include costs-of-care conversations and financial navigation [20,84]. While patient-level interventions might mitigate the high costs of care, it should be emphasized that for some patients no amount of financial counseling can help them handle the costs of care [68]. Therefore policy interventions are also greatly needed [85]. More research is needed on ways to reduce the costs of care and help patients maintain employment [44]. The role of wealth in financial burden has largely been ignored in research on people with cancer because income is easier to measure; future research is needed to determine what types of wealth (savings, property) are most protective and how best to mitigate the effects of costs of care for patients without sufficient wealth.

Conclusion

Financial burden after cancer remains a substantial public health problem. Previous models of financial burden were descriptive and did not include causal relationships and outcomes. This paper puts forth a comprehensive model of the causes, moderators and types of financial burden, as well as clinical outcomes likely to be affected by financial problems. More research on financial burden is primarily needed in three areas. First, improved measures of patient-level financial burden are needed; a key part of developing these measures will be testing the validity of the proposed model. Second, more specificity is needed on the risk and protective factors associated with different types of financial burden. Lastly, research testing a variety of financial interventions is needed to determine the best treatment for a specific patient facing a specific type of financial burden. Although we have focused mostly on patient and caregiver financial burden, clinic and policy factors can greatly affect financial burden and continued research is warranted on the best societal and clinic policies for preventing it.

Future perspective

Understanding of the different types of financial burden and how these affect outcomes may improve. The effects of various causal factors on each type of financial burden may become clear, leading to policy changes that reduce costs of cancer care and improve employment for people with cancer. Patient-level interventions, such as financial navigation or financial counseling, could become a standard of care in oncology settings.

Executive summary.

Causes of financial burden

Causes of financial burden include variable (out-of-pocket costs) and nonvariable medical costs (premiums, taxes), nonmedical costs (transportation, childcare) and employment changes.

Moderators of financial burden

Moderators include precancer health and precancer socioeconomic status, particularly wealth.

Organizational factors such as policies on sending bills to collections can also moderate financial burden.

Material financial burden

Financial burden can be divided into material burden (e.g., financial consequences) or financial coping behaviors (e.g., cost-related nonadherence).

Financial coping behaviors can be focused on affording healthcare or on paying for basic needs.

Psychological financial burden

Financial burden can also be psychological. Psychological financial burden can be future-focused in the form of worry or can take the form of rumination over previous material burden.

Patients may worry about paying for healthcare-specific costs or for basic needs.

Levels of the model

Causes and moderators can be at the patient and family level (income, wealth), organizational level (cost-of-care conversations) and policy level (enforcement of employment accommodations).

Outcomes associated with financial burden

Outcomes affected by financial burden include quality of life, morbidity and mortality.

Measures of financial burden

Current measures of financial burden in cancer are not based on theory and additional patient-reported measures are needed.

Recommendations for future research

Many types of patient-level financial interventions are available, but the types of financial burden alleviated are not fully understood.

Measures of material and psychological financial burden are needed.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: •• of considerable interest

- 1.Financial Toxicity and Cancer Treatment. (PDQ®) – Health Professional Version. Institute, NC, MD, USA: (2017). www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/managing-care/track-care-costs/financial-toxicity-hp-pdq [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Summarizes research on financial burden in the USA.

- 2.Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, Richardson LC, Howard D, Sabatino SA, Finkelstein EA. Cancer treatment cost in the United States: has the burden shifted over time? Cancer 116(14), 3477–3484 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khera N, Chang YH, Hashmi S. et al. Financial burden in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 20(9), 1375–1381 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP. et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 34(3), 259–267 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 122(8), 283–289 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA. et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J. Clin. Oncol. 32(12), 1269–1276 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huntington SF, Weiss BM, Vogl DT. et al. Financial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot study. Lancet Haematol. 2(10), e408–416 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K. et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 123(3), 476–484 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C. et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J. Oncol. Pract. 10(3), 162–167 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology 22(4), 745–755 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, Nedjat-Haiem F, Lee PJ, Vourlekis B. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: effects on quality of life. Cancer 112(3), 616–625 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R. et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors' quality of life. J. Oncol. Pract. 10(5), 332–338 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton JG, Wu LM, Austin JE. et al. Economic survivorship stress is associated with poor health-related quality of life among distressed survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology 22(4), 911–921 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34(15), 1732–1740 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park J, Look KA. Relationship between objective financial burden and the health-related quality of life and mental health of patients with cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 14(2), e113–e121 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology 27(2), 80–149 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith GL, Lopez-Olivo MA, Advani PG. et al. Financial burdens of cancer treatment: a systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 17(10), 1184–1192 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR. et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34(9), 980–986 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Links financial burden to mortality.

- 19.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part II: how can we help with the burden of treatment-related costs? Oncology 27(4), 253–254(2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henrikson NB, Tuzzio L, Loggers ET, Miyoshi J, Buist DS. Patient and oncologist discussions about cancer care costs. Support. Care Cancer 22(4), 961–967 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 109 (2), djw205 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Systematic review of financial burden.

- 22.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ. A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: we can't pay the co-pay. Patient 10(3), 295–309 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Systematic review of financial burden.

- 23.Francoeur RB. Cumulative financial stress and strain in palliative radiation outpatients: the role of age and disability. Acta Oncol. 44(4), 369–381 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Descriptive model of financial burden.

- 24.Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68(2), 153–165 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobkin C, Finkelstein A, Kluender R, Notowidigdo MJ. The economic consequences of hospital admissions. Am. Econ. Rev. 102(2), 308–352 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Haigh EA. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: the generic cognitive model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10, 1–24 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 1–26 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halbesleben JRB, Neveu J-P, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M. Getting to the ‘COR’: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manage. 40(5), 1334–1364 (2014). [Google Scholar]; •• Summarizes conservation of resources theory and related research.

- 29.Hanly P, Maguire R, Ceilleachair AO, Sharp L. Financial hardship associated with colorectal cancer survivorship: the role of asset depletion and debt accumulation. Psychooncology 27(9), 2165–2171 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the ‘financial toxicity’associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 108 5), djv410 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann P, Sanders G, Russell L, Siegel J, Ganiats T. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 536 (2016). [Google Scholar]; •• Findings of the second panel on cost-effectiveness research.

- 32.Carias C, Chesson HW, Grosse SD. et al. Recommendations of the second panel on cost effectiveness in health and medicine: a reference, not a rule book. Am. J. Prev. Med. 54(4), 600–602 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azzani M, Roslani AC, Su TT. The perceived cancer-related financial hardship among patients and their families: a systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 23(3), 889–898 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chirikos TN, Russell-Jacobs A, Cantor AB. Indirect economic effects of long-term breast cancer survival. Cancer Pract. 10(5), 248–255 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longo CJ, Deber R, Fitch M, Williams AP, D'Souza D. An examination of cancer patients’ monthly ‘out-of-pocket’ costs in Ontario, Canada. Eur. J. Cancer Care 16(6), 500–507 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauzier S, Levesque P, Drolet M. et al. Out-of-pocket costs for accessing adjuvant radiotherapy among Canadian women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 29(30), 4007–4013 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Housser E, Mathews M, Lemessurier J, Young S, Hawboldt J, West R. Responses by breast and prostate cancer patients to out-of-pocket costs in Newfoundland and Labrador. Curr. Oncol. 20(3), 158–165 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Oliveira C, Bremner KE, Ni A, Alibhai SM, Laporte A, Krahn MD. Patient time and out-of-pocket costs for long-term prostate cancer survivors in Ontario, Canada. J. Cancer Surviv. 8(1), 9–20 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lauzier S, Maunsell E, Drolet M. et al. Wage losses in the year after breast cancer: extent and determinants among Canadian women. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 100(5), 321–332 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mojahedian MM, Toroski M, Keshavarz K, Aghili M, Zeyghami S, Nikfar S. Estimating the cost of illness of prostate cancer in Iran. Clin. Ther. 41(1), 50–58 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longo CJ, Fitch M, Deber RB, Williams AP. Financial and family burden associated with cancer treatment in Ontario, Canada. Support. Care Cancer 14(11), 1077–1085 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baird KE. Recent trends in the probability of high out-of-pocket medical expenses in the United States. SAGE Open Med. 4, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hazell SZ, Fu W, Hu C. et al. Financial toxicity in lung cancer: an assessment of magnitude, perception, and impact on quality of life. Ann. Oncol. 31(1), 96–102 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R, Rabin B, Nutt S, Chubak J. Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: results from a multisite study. J. Cancer Surviv. 10(6), 1104–1111 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Pinheiro LC, Carey LA, Olshan AF, Reeder-Hayes KE. Racial differences in the financial impact of breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 35(Suppl. 15), e18293 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer 119(5), 1050–1057 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.George N, Grant R, James A, Mir N, Politi MC. Burden associated with selecting and using health insurance to manage care costs: results of a qualitative study of nonelderly cancer survivors. Med. Care Res. Rev. (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imber BS, Varghese M, Ehdaie B, Gorovets D. Financial toxicity associated with treatment of localized prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 17(1), 28–40 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones SMW, Chennupati S, Nguyen T, Fedorenko C, Ramsey SD. Comorbidity is associated with higher risk of financial burden in Medicare beneficiaries with cancer but not heart disease or diabetes. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(1), e14004 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanislawski K. The coping circumplex model: an integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front. Psychol. 10, 694 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ehring T, Watkins ER. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 1(3), 192–205 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones SMW, Walker R, Fujii M, Nekhlyudov L, Rabin BA, Chubak J. Financial difficulty, worry about affording care, and benefit finding in long-term survivors of cancer. Psychooncology 27(4), 1320–1326 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carney CE, Harris AL, Moss TG, Edinger JD. Distinguishing rumination from worry in clinical insomnia. Behav. Res. Ther. 48(6), 540–546 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ciesla JA, Dickson KS, Anderson NL, Neal DJ. Negative repetitive thought and college drinking: angry rumination, depressive rumination, co-rumination, and worry. Cognit. Ther. Res. 35, 142–150 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aldao A, Mennin DS, McLaughlin KA. Differentiating worry and rumination: evidence from heart rate variability during spontaneous regulation. Cognit. Ther. Res. 37(3), 613–619 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lewis EJ, Yoon KL, Joormann J. Emotion regulation and biological stress responding: associations with worry, rumination, and reappraisal. Cogn. Emot. 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong RY. Worry and rumination: differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behavior. Behav. Res. Ther. 45(2), 277–290 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crowley MJ, Zullig LL, Shah BR. et al. Medication non-adherence after myocardial infarction: an exploration of modifying factors. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 30(1), 83–90 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shapiro GK, Burchell BJ. Measuring financial anxiety. J. Neurosci. Psychol. Econ. 5(2), 92–103 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 32(4), 306–311 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE, Carroll NV. Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. J. Manage. Care Spec. Pharm. 20(7), 669–675 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jerndal P, Ringstrom G, Agerforz P. et al. Gastrointestinal-specific anxiety: an important factor for severity of GI symptoms and quality of life in IBS. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 22(6), 646–e179 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buss C, Davis EP, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Maternal pregnancy-specific anxiety is associated with child executive function at 6–9 years age. Stress 14(6), 665–676 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. : Annals of Child Development. Vasta R. (). Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK, 6, 187–249(1989). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones SMW, Nguyen T, Chennupati S. Association of financial burden with self-rated and mental health in older adults with cancer. J. Aging Health 32(5-6) 394–400 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH. et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 126(2), 529–537 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adrion ER, Ryan AM, Seltzer AC, Chen LM, Ayanian JZ, Nallamothu BK. Out-of-pocket spending for hospitalizations among nonelderly adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 176(9), 1325–1332 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Majhail NS, Mau LW, Denzen EM, Arneson TJ. Costs of autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States: a study using a large national private claims database. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48(2), 294–300 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Hahn T. et al. Pilot study of patient and caregiver out-of-pocket costs of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48(6), 865–871 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agency for Health care Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. MD, USA: (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lauzier S, Maunsell E, Drolet M, Coyle D, Hebert-Croteau N. Validity of information obtained from a method for estimating cancer costs from the perspective of patients and caregivers. Qual. Life Res. 19(2), 177–189 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Washington State Department of Health. Guidelines for using rural-urban classification systems for community health assessment. Health Olympia, WA, USA: (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paez KA, Mallery CJ, Noel H. et al. Development of the Health Insurance Literacy Measure (HILM): conceptualizing and measuring consumer ability to choose and use private health insurance. J. Health Commun. 19(Suppl. 2), 225–239 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 47(11), 1245–1251 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Measuring financial well-being: a guide to using the CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale. Bureau, CFP Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Washington, DC: (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Archuleta KL, Dale A, Spann SM. College students and financial distress: exploring debt, financial satisfaction, and financial anxiety. J. Financial Couns. Plan. 24(2), 50–62 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O'Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. Financial Couns. Plan. 17(1), 34–50 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Syrjala KL, Yi JC, Langer SL. Psychometric properties of the Cancer and Treatment Distress (CTXD) measure in hematopoietic cell transplantation patients. Psychooncology 25(5), 529–535 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones SMW, Amtmann D. Health care worry is associated with worse outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil. Psychol. 59(3), 354–359 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones SM, Amtmann D. Differential item function analysis of a scale measuring worry about affording healthcare in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil. Psychol. 61(4), 430–434 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Veenstra CM, Regenbogen SE, Hawley ST. et al. A composite measure of personal financial burden among patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Med. Care 52(11), 957–962 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.National Center for Health Statistics. Survey Description, National Health Interview Survey, 2017. Statistics, NCfH Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, MD, USA: (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wiggins R. Financial Wellness Continuum. (2019). www.afcpe.org/news-and-publications/blog/working-together-to-strengthen-the-continuum-of-care/ [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J. et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J. Oncol. Pract. 14(2), e122–e129 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Greenbaum Z. Pathways for addressing deep poverty. Monitor Psychol. 50(7), 32 (2019). [Google Scholar]