To date, the development of mRNA vaccines for the prevention of infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been a success story, with no serious concerns identified in the ongoing phase 3 clinical trials.1 Minor local side effects such as pain, redness, and swelling have been observed more frequently with the vaccines than with placebo. Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle and joint pain have also been somewhat more common with the vaccines than with placebo, and most have occurred during the first 24 to 48 hours after vaccination.1 In the phase 1–3 clinical trials of the Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines, potential participants with a history of an allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine were excluded. The Pfizer–BioNTech studies also excluded participants with a history of severe allergy associated with any vaccine (see the protocols of the two trials, available with the full text of the articles at NEJM.org, for full exclusion criteria).1,2 Hypersensitivity adverse events were equally represented in the placebo (normal saline) and vaccine groups in both trials.1

The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the United Kingdom was the first to authorize emergency use of the Pfizer–BioNTech mRNA vaccine. On December 8, 2020, within 24 hours after the start of the U.K. mass vaccination program for health care workers and elderly adults, the program reported probable cases of anaphylaxis in two women, 40 and 49 years of age, who had known food and drug allergies and were carrying auto-injectable epinephrine. On December 11, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer–BioNTech mRNA vaccine, and general vaccination of health care workers was started on Monday, December 14. On December 15, a 32-year-old female health care worker in Alaska who had no known allergies presented with an anaphylactic reaction within 10 minutes after receiving the first dose of the vaccine. The participants who had these initial three reported cases of anaphylaxis would not have been excluded on the basis of their histories from the mRNA vaccine clinical trials.1,2 Since the index case in Alaska, several more cases of anaphylaxis associated with the Pfizer mRNA vaccine have been reported in the United States after vaccination of almost 2 million health care workers, and the incidence of anaphylaxis associated with the Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine appears to be approximately 10 times as high as the incidence reported with all previous vaccines, at approximately 1 in 100,000, as compared 1 in 1,000,000, the known and stable incidence of anaphylaxis associated with other vaccines. The EUA for the Moderna mRNA vaccine was issued on December 18, and it is currently too soon to know whether a similar signal for anaphylaxis will be associated with that vaccine; however, at this time a small number of potential cases of anaphylaxis have been reported, including one case on December 24 in Boston in a health care worker with shellfish allergy who was carrying auto-injectable epinephrine.

In response to the two cases of anaphylaxis in the United Kingdom, the MHRA issued a pause on vaccination with the Pfizer–BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine, to exclude any person with a history of anaphylactic reaction to any food, drug, or vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued advice pertaining to administration of either the first or the second dose of the Pfizer–BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccine, recommending exclusion of any person who has a history of a severe or immediate (within 4 hours) allergic reaction associated with any of the vaccine components, including polyethylene glycol (PEG) and PEG derivatives such as polysorbates.3

Anaphylaxis is a serious multisystem reaction with rapid onset and can lead to death by asphyxiation, cardiovascular collapse, and other complications.4 It requires prompt recognition and treatment with epinephrine to halt the rapid progression of life-threatening symptoms. The cause of anaphylactic reactions is the activation of mast cells through antigen binding and cross-linking of IgE; the symptoms result from the tissue response to the release of mediators such as histamine, proteases, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes and typically include flushing, hives, laryngeal edema, wheezing, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, hypotension, and cardiovascular collapse. Patients become IgE-sensitized by previous exposure to antigens. Reactions that resemble the clinical signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis, previously known as anaphylactoid reactions, are now referred to as non-IgE–mediated reactions because they do not involve IgE. They manifest the same clinical features and response to epinephrine, but they occur by direct activation of mast cells and basophils, complement activation, or other pathways and can occur on first exposure. Tryptase is typically elevated in blood in IgE-mediated anaphylaxis and, to a lesser extent, in non–IgE-mediated mast-cell activation, a feature that identifies mast cells as the sources of inflammatory mediators. Prick and intradermal skin testing and analysis of blood samples for serum IgE are used to identify the specific drug culprit, although the tests lack 100% negative predictive value.5 The clinical manifestations of the two U.K. cases and the one U.S. case fit the description of anaphylaxis: they occurred within minutes after the injections, symptoms were typical, and all responded to epinephrine. The occurrence on first exposure is not typical of IgE-mediated reactions; however, preexisting sensitization to a component of the vaccine could account for this observation.4

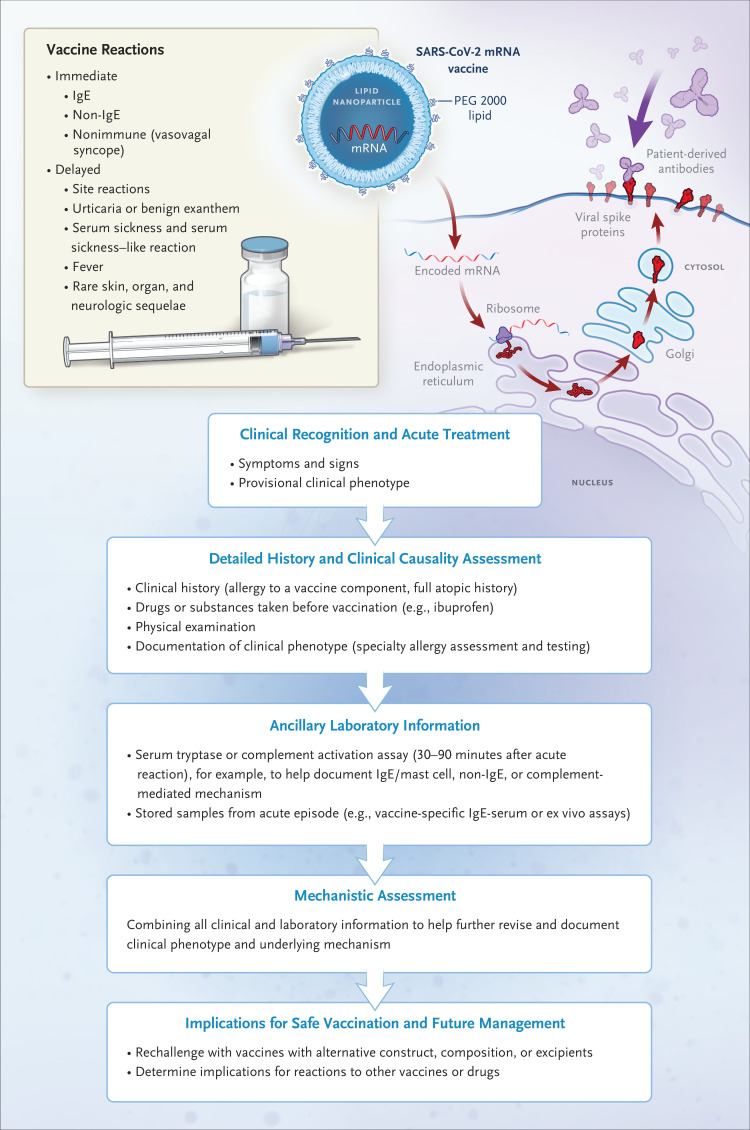

Anaphylaxis is a treatable condition with no permanent effects. Nevertheless, news of these reactions has raised fear about the risks of a new vaccine in a community. These cases of anaphylaxis raise more questions than they answer; however, such safety signals are almost inevitable as we embark on vaccination of millions of people, and they highlight the need for a robust and proactive “safety roadmap” to define causal mechanisms, identify populations at risk for such reactions, and implement strategies that will facilitate management and prevention (Figure 1).6

Figure 1. Assessing Reactions to Vaccines.

SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines are built on the same lipid-based nanoparticle carrier technology; however, the lipid component of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine differs from that of the Moderna vaccine. Operation Warp Speed has led to an unprecedented response to the study of the safety and effectiveness of new vaccine platforms never before used in humans and to the development of vaccines that have been authorized for use less than a year after the SARS-CoV-2 viral sequence was discovered. The next few months could see the authorization of several such vaccines, and inevitably, adverse drug events will be recognized in the coming months that were not seen in the studies conducted before emergency use authorization. Maintenance of vaccine safety requires a proactive approach to maintain public confidence and reduce vaccine hesitancy. This approach involves not only vigilance but also meticulous response, documentation, and characterization of these events to heighten recognition and allow definition of mechanisms and appropriate approaches to prediction, prevention, and treatment. A systematic approach to an adverse reaction to any vaccine requires clinical recognition and appropriate initial treatment, followed by a detailed history and causality assessment. Nonimmune immediate reactions such as vasovagal reactions are common and typically manifest with diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, pallor, and bradycardia, in contrast to the flush, pruritus, urticaria, angioedema, tachycardia, and laryngeal edema seen with anaphylaxis. Post-reaction clinical assessment by an allergist–immunologist that includes skin testing for allergy to components of the vaccine can be helpful. Use of other laboratory information may aid in clinical and mechanistic assessment and guide future vaccine and drug safety as well as management, such as rechallenge with alternative vaccines if redosing is required. A useful resource for searching the excipients of drugs and vaccines is https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/. A useful resource for excipients in licensed vaccines is https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/appendices/b/excipient-table-2.pdf.

We can be reassured that vaccine-associated anaphylaxis has been a rare event, at one case per million injections, for most known vaccines.6 Acute allergic reactions after vaccination might be caused by the vaccine antigen, residual nonhuman protein, or preservatives and stabilizers in the vaccine formulation, also known as excipients.6 Although local reactions may be commonly associated with the active antigen in the vaccine, IgE-mediated reactions or anaphylaxis have historically been more typically associated with the inactive components or products of the vaccine manufacturing process, such as egg, gelatin, or latex.6

The mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer–BioNtech and Moderna use a lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system that prevents the rapid enzymatic degradation of mRNA and facilitates in vivo delivery.1,2,7 This lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system is further stabilized by a polyethylene glycol (PEG) 2000 lipid conjugate that provides a hydrophilic layer, prolonging half-life. Although the technology behind mRNA vaccines is not new, there are no licensed mRNA vaccines, and the Pfizer–BioNtech and Moderna vaccines are the first to receive an EUA. There is therefore no prior experience that informs the likelihood or explains the mechanism of allergic reactions associated with mRNA vaccines. It is possible that some populations are at higher risk for non–IgE-mediated mast-cell activation or complement activation related to either the lipid or the PEG-lipid component of the vaccine. By comparison, formulations such as pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are associated with infusion reactions in up to 40% of recipients; the reactions are presumed to be caused by complement activation that occurs on first infusion, without previous exposure to the drug, and they are attenuated with second and subsequent injections.8

PEG is a compound used as an excipient in medications and has been implicated as a rare, “hidden danger” cause of IgE-mediated reactions and recurrent anaphylaxis.9 The presence of lipid PEG 2000 in the mRNA vaccines has led to concern about the possibility that this component could be implicated in anaphylaxis. To date, no other vaccine that has PEG as an excipient has been in widespread use. The risk of sensitization appears to be higher with injectable drugs with higher-molecular-weight PEG; anaphylaxis associated with bowel preparations containing PEG 3350 to PEG 4000 has been noted in case reports.9,10 The reports include anaphylaxis after a patient was exposed to a PEG 3350 bowel preparation; anaphylaxis subsequently developed on the patient’s first exposure to a pegylated liposome microbubble, PEGLip 5000 perflutren echocardiography contrast (Definity), which is labeled with a warning about immediate hypersensitivity reactions.11 For drugs such as methylprednisolone acetate and injectable medroxyprogesterone that contain PEG 3350, it now appears that the PEG component is more likely than the active drug to be the cause of anaphylaxis.9,12 For patients with a history of an anaphylactic reaction to the SARS-CoV-2 Pfizer–BioNTech mRNA vaccine, the risk of anaphylaxis with the Moderna SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine — whose delivery system is also based on PEG 2000, but with different respective lipid mixtures (see Table 1) — is unknown. The implications for future use of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines with an adenovirus carrier and protein subunit, which are commonly formulated with polysorbate 80, a nonionic surfactant and emulsifier that has a structure similar to PEG, are also currently unknown.6,13 According to the current CDC recommendations, all persons with a history of an anaphylactic reaction to any component of the mRNA SARS-Cov-2 vaccines should avoid these vaccines, and this recommendation would currently exclude patients with a history of immediate reactions associated with PEG. It would also currently exclude patients with a history of anaphylaxis after receiving either the BioNTech–Pfizer or the Moderna vaccine, who should avoid all PEG 2000–formulated mRNA vaccines, and all PEG and injectable polysorbate 80 products, until further investigations are performed and more information is available.

Table 1. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) or in Late-Phase Studies.

| Vaccine Platform | Type of Vaccine and Immunogen |

Developer (Name of Vaccine) |

Dose Schedule and Administration |

Phase* | Excipients† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-based vaccine |

|

BioNTech–Pfizer (BNT162b2) |

|

Post-EUA | 0.43 mg ((4-hydroxybutyl)azanediyl)bis(hexane-6,1-diyl)bis(2-hexyldecanoate), 0.05 mg 2[(polyethylene glycol)-2000]-N,N-ditetradecylacetamide, 0.09 mg 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, and 0.2 mg cholesterol, 0.01 mg potassium chloride, 0.01 mg monobasic potassium phosphate, 0.36 mg sodium chloride, 0.07 mg dibasic sodium phosphate dihydrate, and 6 mg sucrose. The diluent (0.9% sodium chloride Injection) contributes an additional 2.16 mg sodium chloride per dose |

| RNA-based vaccine |

|

Moderna (mRNA-1273) |

|

Post-EUA | Lipids (SM-102; 1,2-dimyristoyl-rac-glycero-3-methoxypolyethylene glycol-2000 [PEG 2000-DMG]; cholesterol; and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine [DSPC]), tromethamine, tromethamine hydrochloride, acetic acid, sodium acetate, and sucrose |

| Adenovirus vector (nonreplicating) |

|

AstraZeneca and University of Oxford (AZD1222) |

|

Phase 3 | 10 mM histidine, 7.5% (w/v) sucrose, 35 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM magnesium chloride, 0.1% (w/v) polysorbate 80, 0.1 mM edetate disodium, 0.5% (w/v) ethanol, at pH 6.6 |

| Adenovirus vector (nonreplicating) |

|

Janssen |

|

Phase 3 | Sodium chloride, citric acid monohydrate, polysorbate 80, 2 hydroxypropyl-B-cyclodextrin (HBCD), ethanol (absolute), sodium hydroxide |

| Protein subunit |

|

Novavax |

|

Phase 3 | Matrix M1 adjuvant Full-length spike protein formulated in polysorbate 80 detergent and Matrix M1 adjuvant |

| Protein subunit |

|

Sanofi Pasteur and GSK |

|

Phase 1–2 | Sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate, sodium phosphate dibasic, sodium chloride polysorbate 20, disodium hydrogen phosphate, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, potassium chloride |

Phase information was current as of December 21, 2020. In all cases, the placebo was normal saline.

Bold entries are excipients potentially related to vaccine reaction that may be cross-reactive to other excipients (e.g., PEG 2000 and polysorbate 80). SM-102, a component of the Moderna vaccine, is a proprietary ionizable lipid.

We are now entering a critical period during which we will move rapidly through phased vaccination of various priority subgroups of the population. In response to the cases of anaphylaxis associated with the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine in the United Kingdom and now several cases of anaphylaxis in the United States, the CDC has recommended that only persons with a known allergy to any component of the vaccine be excluded from vaccination. A systematic approach to the existing hypersensitivity cases and any new ones will ensure that our strategy will maintain safety not only for this vaccine but for future mRNA and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines with shared or similar components (Figure 1 and Table 1).6

The next few months alone are likely to see at least five new vaccines on the U.S. market, with several more in development (Table 1).13 Maintaining public confidence to minimize vaccine hesitancy will be crucial.14,15 As in any post-EUA program, adverse events that were not identified in clinical trials are to be expected. In addition, populations that have been studied in clinical trials may not reflect a predisposition to adverse events that may exist in other populations.16 Regardless of the speed of development, some adverse events are to be expected with all drugs, vaccines, and medicinal products. Fortunately, immune-mediated adverse events are rare. Because we are now entering a period during which millions if not billions of people globally will be exposed to new vaccines over the next several months, we must be prepared to develop strategies to maximize effectiveness and safety at an individual and a population level. The development of systematic and evidence-based approaches to vaccination safety will also be crucial, and the approaches will intersect with our knowledge of vaccine effectiveness and the need for revaccination. When uncommon side effects that are prevalent in the general population are observed (e.g., the four cases of Bell’s palsy reported in the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine trial group), the question whether they were truly vaccine-related remains to be determined.1

If a person has a reaction to one SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, what are the implications for the safety of vaccination with a different SARS-CoV-2 vaccine? Furthermore, what safety issues may preclude future vaccination altogether? Indeed, mRNA vaccines are a promising new technology, and demonstration of their safety is relevant to the development of vaccines against several other viruses of global importance and many cancers.7 For the immediate future, during a pandemic that is still increasing, it is critical that we focus on safe and efficient approaches to implementing mass vaccination. In the future, however, these new vaccines may mark the beginning of an era of personalized vaccinology in which we can tailor the safest and most effective vaccine on an individual and a population level.17 Moreover, postvaccination surveillance and documentation may present a challenge. On a public health level, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS; https://vaers.hhs.gov) is a national reporting system designed to detect early safety problems for licensed vaccines, but in the case of Covid-19 vaccines, the system will serve the same function after an EUA has been issued. On an individual level, a system that will keep track of the specific SARS-CoV-2 vaccine received and will provide a means to monitor potential long-term vaccine-related adverse events will be critical to individual safety and efficacy. V-safe (https://cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/vsafe.html) is a smartphone application designed to remind patients to obtain a second dose as needed and to track and manage Covid-19 vaccine–related side effects.

In the world of Covid-19 and vaccines, many questions remain. What are the correlates of protective immunity after natural infection or vaccination? How long will immunity last? Will widespread immunity limit the spread of the virus in the population? Which component of the vaccine is responsible for allergic reactions? Are some vaccines less likely than others to cause IgE- and non-IgE–mediated reactions? Careful vaccine-safety surveillance over time, paired with elucidation of mechanisms of adverse events across different SARS-CoV-2 vaccine platforms, will be needed to inform a strategic and systematic approach to vaccine safety.

Disclosure Forms

This article was published on December 30, 2020, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2603-2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1920-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1857-1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochner BS, Lichtenstein LM. Anaphylaxis. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1785-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castells M. Diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis in precision medicine. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140:321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone CA Jr, Rukasin CRF, Beachkofsky TM, Phillips EJ. Immune-mediated adverse reactions to vaccines. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2019;85:2694-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW, Weissman D. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018;17:261-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chanan-Khan A, Szebeni J, Savay S, et al. Complement activation following first exposure to pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): possible role in hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Oncol 2003;14:1430-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone CA Jr, Liu Y, Relling MV, et al. Immediate hypersensitivity to polyethylene glycols and polysorbates: more common than we have recognized. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7(5):1533-1540.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sellaturay P, Nasser S, Ewan P. Polyethylene glycol-induced systemic allergic reactions (anaphylaxis). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020. October 1 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krantz MS, Liu Y, Phillips EJ, Stone CA Jr. Anaphylaxis to PEGylated liposomal echocardiogram contrast in a patient with IgE-mediated macrogol allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(4):1416-1419.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu IN, Rutkowski K, Kennard L, Nakonechna A, Mirakian R, Wagner A. Polyethylene glycol may be the major allergen in depot medroxy-progesterone acetate. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8:3194-3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 2020;586:516-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes, and Narratives Survey (OCEANS) II. Psychol Med 2020. December 11 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 2020. October 20 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-α-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1109-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Kennedy RB. Personalized vaccinology: a review. Vaccine 2018;36:5350-5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.