Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the literature pertaining to asynchronous automated electronic notifications of laboratory results to clinicians.

Methods

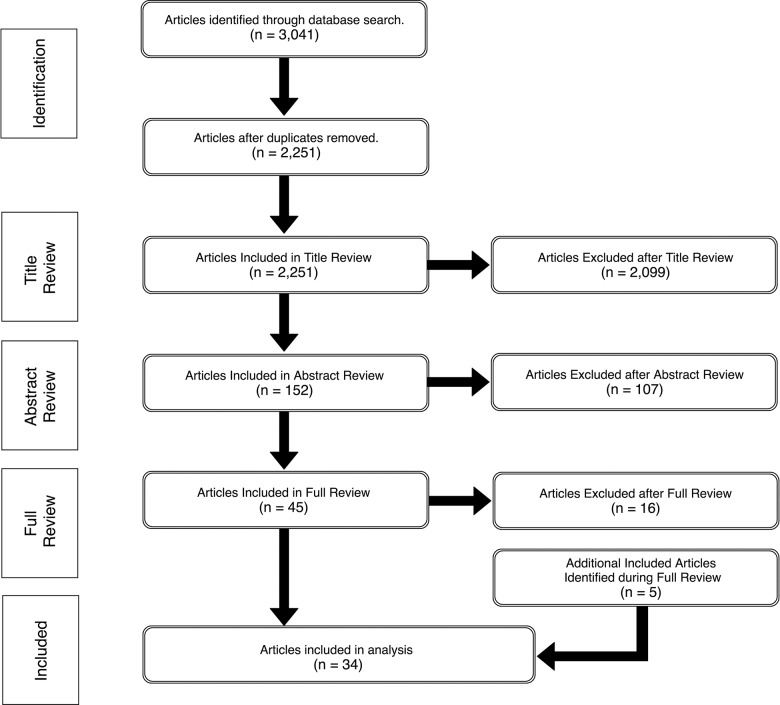

PubMed, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Collaboration were queried for studies pertaining to automated electronic notifications of laboratory results. A title review was performed on the primary results, with a further abstract review and full review to produce the final set of included articles.

Results

The full review included 34 articles, representing 19 institutions. Of these, 19 reported implementation and design of systems, 11 reported quasi-experimental studies, 3 reported a randomized controlled trial, and 1 was a meta-analysis. Twenty-seven articles included alerts of critical results, while 5 focused on urgent notifications and 2 on elective notifications. There was considerable variability in clinical setting, system implementation, and results presented.

Conclusion

Several asynchronous automated electronic notification systems for laboratory results have been evaluated, most from >10 years ago. Further research on the effect of notifications on clinicians as well as the use of modern electronic health records and new methods of notification is warranted to determine their effects on workflow and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: notifications, alerts, laboratory, critical, automated

INTRODUCTION

Health care delivery is increasingly data-driven. Automated clinical notifications have become widespread throughout hospitals, frequently providing appropriate and necessary warnings to improve care, but also leading to alarm fatigue, potentially harming patients.1,2 While many forms of health care notification systems exist,3–5 critical laboratory notification systems were among the first and most studied.6–8

When clinicians fail to respond to laboratory results in a timely manner, potential for patient harm exists.9 Time-lag between laboratory results availability and physician action is well documented.10,11 Traditionally, critical lab values have been communicated via phone calls from laboratory technicians to health care providers12; however, this has limitations.11 Many novel health information technology (HIT) interventions have been studied to improve physicians’ responses to important laboratory results,6,10,12–15 and these results can be in the form of critical alerts that require immediate action,6,10,13,16–18 urgent notifications that need a prompt response,19–21 or elective notifications14,15 that are based on selected criteria and may or may not contain critical information. All of these interventions are asynchronous, as they are triggered by events other than the clinician’s interaction with the system.13

The potential to improve clinical decision-making22 must be balanced against the potential negative impact of information overload.23 Given the recent achievement of near-ubiquitous adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) in US hospitals and the growth of new technologies such as Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources that extend the functionality of EHR systems in novel ways,24 the time is ripe for a review of the literature on automated clinical laboratory notifications. Understanding the current state of the science in this area will guide the development of innovative tools to provide clinicians with the right information in the right context for improving patient care, while limiting the alert fatigue burden.

OBJECTIVE

We provide a systematic review of the available scientific literature on the subject of critical, urgent, and elective asynchronous automated electronic laboratory result notifications. We summarize the current methods by which health care providers are notified of laboratory results, describe established systems to support this process, and consider objectives for future innovations.

METHODS

Systematic review

Our review methodology followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis, which consists of guidelines designed to aid authors in improving the quality of review reports.25,26

Search process

We searched 3 bibliographic databases (PubMed, Web of Science [WOS], and the Cochrane Collaboration Database), including all entries published through June 2016. Through an iterative process, a specific set of keywords, topics, titles, and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms (PubMed and Cochrane) or research areas (WOS) were recognized. These included terms in titles identifying automation (“computer,” “real-time,” “automat*”) and notifications (“notification”, “alert*,” “critical”), as well as the keyword “Laboratory” and the MeSH term or research area “Medical Informatics.” With the exception of the differences in MeSH term and research area (for PubMed and Cochrane vs WOS, respectively), the same search was conducted in all 3 databases. Articles without an English full text were excluded.

Article selection

The resulting titles were combined and duplicates were removed. Primary evaluation was performed by 1 of the authors (BHS), screening titles for inclusion. A secondary screening was then performed by 2 authors (BHS and TAN) based on associated abstracts, with calculation of interrater reliability with Cohen’s kappa. Disagreements were resolved by a third author (DKV). Full review of each article was then conducted. Reference lists of included articles were screened for any further titles to include in the full review.

RESULTS

Title review

Our search resulted 3041 titles: 2139 from PubMed, 657 from WOS, and 245 from Cochrane. After removing duplicates, 2251 articles remained. After title review, 2099 were excluded, as they predominantly described bench work automation, laboratory information systems, or synchronous clinical decision support systems (CDSSs).

Abstract review

Of the 152 articles in abstract review, 40 were agreed upon by the 2 reviewers to be included and 89 to be excluded, for similar reasons to those excluded from title review. There was disagreement regarding 23 articles. Interrater reliability for abstract review was moderate, with κ = 0.7.

Five of the 23 articles with disagreements were included for full review after a third author evaluation.

Full review

Of the 45 articles included for full review, 16 were excluded, predominantly because they contained information on non-automated interventions, non-laboratory notifications, non-clinical notifications, or needs assessment studies. Conference proceeding publications were included. Twenty-nine articles remained after the full review process. Five additional articles from citations met the inclusion criteria, resulting in 34 articles. The inclusion and exclusion process is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article identification and review process.

Included articles

There were 19 institutions represented in our results. Of the included studies, 19 reported implementations, 11 reported quasi-experimental studies, 3 reported randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and 1 was a meta-analysis. Twenty-seven studies examined alerts of critical results, while 5 focused on urgent notifications and 2 studied elective notifications. The study design, author, acuity, and form(s) of notification, as well as the institution at which the tool was implemented, are shown in Table 1. Table 2 summarizes the included experimental studies and provides a description of their methods and pertinent results. Table 3 shows the number of publications evaluating automated laboratory notification systems by decade.

Table 1.

List of articles included in systematic review

| Title | Year | First Author | Study Design | Acuity | Notification | Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A computerized alert program for acutely ill patients18 | 1980 | Johnson | Implementation | Critical | Terminal | Latter Day Saints Hospital |

| Decision support alerts for clinical laboratory and blood gas data27 | 1980 | Shabot | Implementation | Critical | Terminal | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center |

| Application of a computerized medical decision-making process to the problem of digoxin intoxication28 | 1984 | White | RCT | Critical | Printout | Latter Day Saints Hospital |

| Development of a computerized laboratory alerting system29 | 1989 | Bradshaw | Implementation | Critical | Terminal | Latter Day Saints Hospital |

| Inferencing strategies for automated alerts on critically abnormal laboratory and blood gas data30 | 1989 | Shabot | Implementation | Critical | Terminal | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center |

| A computerized laboratory alerting system6 | 1990 | Tate | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Terminal | Latter Day Saints Hospital |

| The effect of computer-based reminders on the management of hospitalized patients with worsening renal function31 | 1991 | Rind | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital | |

| Computers, quality, and the clinical laboratory: a look at critical value reporting32 | 1993 | Tate | Implementation | Critical | Pager | Latter Day Saints Hospital |

| Effect of computer-based alerts on the treatment and outcomes of hospitalized patients17 | 1994 | Rind | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital | |

| Nurses, pagers, and patient-specific criteria: three keys to improved critical value reporting12 | 1995 | Tate KE | Implementation | Critical | Pager | Latter Day Saints Hospital |

| Real-time wireless decision support alerts on a Palmtop PDA33 | 1995 | Shabot | Implementation | Critical | Phone | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center |

| Detecting alerts, notifying the physician, and offering action items: a comprehensive alerting system10 | 1996 | Kuperman | Implementation | Critical | Pager | Brigham and Women’s Hospital |

| Advanced alerting features: displaying new relevant data and retracting alerts34 | 1997 | Kuperman | Implementation | Critical | Pager | Brigham and Women’s Hospital |

| Clinical event monitoring at the University of Pittsburgh13 | 1997 | Wagner | Implementation | Critical | Pager | University of Pittsburg |

| A computerized laboratory alerting system in a psychogeriatric unit20 | 1998 | Modai | Implementation | Urgent | Terminal | Gehah Psychiatric Hospital |

| An alert system for ED laboratory test results21 | 1998 | Dong | Implementation | Urgent | Boston Children’s Hospital | |

| Improving response to critical laboratory results with automation: results of a randomized controlled trial35 | 1999 | Kuperman | RCT | Critical | Pager | Brigham and Women’s Hospital |

| Wireless clinical alerts for physiologic, laboratory and medication data36 | 2000 | Shabot | Implementation | Critical | Pager | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center |

| A comprehensive computerized critical laboratory results alerting system for ambulatory and hospitalized patients37 | 2001 | Lordache | Implementation | Critical | Phone | Soroka University Medical Center |

| Design and implementation of a real-time clinical alerting system for intensive care unit14 | 2002 | Chen | Implementation | Updates | Phone | Taipei Veterans General Hospital |

| Real-time notification of laboratory data requested by users through alphanumeric pagers15 | 2002 | Poon | Implementation | Updates | Pager | Brigham and Women’s Hospital |

| Effect of a computerized alert on the management of hypokalemia in hospitalized patients38 | 2003 | Paltiel | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Terminal | Hadassah Medical Center |

| A trial of automated safety alerts for inpatient digoxin use with computerized physician order entry39 | 2004 | Galanter | Quasi-experimental | Critical |

|

|

| Computerized alerts improve outpatient laboratory monitoring of transplant patients40 | 2008 | Staes | Quasi-experimental | Urgent | Latter Day Saints Hospital | |

| Evaluating the short message service alerting system for critical value notification via PDA telephones41 | 2008 | Park | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Phone | Kangbuk Samsung Hospital |

| Evaluation of effectiveness of a computerized notification system for reporting critical values42 | 2009 | Piva | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Phone | Padua Hospital |

| Implementation of a closed-loop reporting system for critical values and clinical communication in compliance with goals of the joint commission43 | 2010 | Parl | Implementation | Critical | Pager |

|

| Notification of abnormal lab test results in an electronic medical record: do any safety concerns remain?44 | 2010 | Singh | Quasi-experimental | Urgent | Texas VA System | |

| Real-time clinical alerting: effect of an automated paging system on response time to critical laboratory values – a randomized controlled trial16 | 2010 | Etchells | RCT | Critical | Pager |

|

| Computer laboratory notification system via short message service to reduce health care delays in management of tuberculosis in Taiwan45 | 2011 | Chen | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Phone | Koahsiun Medical University |

| Real-time automated paging and decision support for critical laboratory abnormalities46 | 2011 | Etchells | Quasi-experimental | Critical | Phone |

|

| Effectiveness of automated notification and customer service call centers for timely and accurate reporting of critical values: A laboratory medicine best practices systematic review and meta-analysis47 | 2012 | Liebow | Meta-analysis | Critical | Phone | Multiple |

| Technological resources and personnel costs required to implement an automated alert system for ambulatory physicians when patients are discharged from hospitals to home19 | 2012 | Field | Implementation | Urgent | Meyers Primary Care Institute | |

| A simple electronic alert for acute kidney injury29 | 2015 | Flynn | Implementation | Critical |

|

Table 2.

Summary of experimental studies

| Author | Year | Study Design | Brief Description | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tate | 1990 | Quasi-experimental | System identifies life-threatening laboratory conditions and generates alerts to clinicians. Examined appropriate care pre-and post-implementation. |

|

| Rind | 1991 | Quasi-experimental | Notifications sent to physicians of rising creatinine levels for hospitalized patients on nephrotoxic and renally excreted medications. Examined medication adjustment pre- and post-implementation with prospective time series. |

|

| Rind | 1994 | Quasi-experimental | Conducted prospective time series of computerized alerts on rising creatinine levels (a continuation of the study above). |

|

| Paltiel | 2003 | Quasi-experimental | Computerized alert sent for patients whose serum potassium dropped to critically low levels. Examined pre- and post-implementation. |

|

| Galanter | 2004 | Quasi-experimental | Clinician notified of missing or abnormal electrolytes for those patients prescribed digoxin at time of order entry and notified of hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia upon laboratory result. Examined pre- and post-implementation. |

|

| Staes | 2008 | Quasi-experimental | Compared computerized alerts of outpatient laboratory monitoring for transplant patients to traditional faxes and printouts. |

|

| Park | 2008 | Quasi-experimental | Clinicians were notified by Short Message Service (SMS) of critical potassium values sent to a personal digital assistant and compared to historical data from the same institution. |

|

| Piva | 2009 | Quasi-experimental | Compared computerized alerts delivered by e-mail and SMS to phone calls for study periods prior to and after implementation. |

|

| Singh | 2010 | Quasi-experimental | Generated alerts for outpatient management of positive hepatitis C antibody as well as elevated prostate-specific antigen, hemoglobin A1c, or thyroid-stimulating hormone, and tracked acknowledgments within 2 weeks. Compared unacknowledged to acknowledged alerts. |

|

| Chen | 2011 | Quasi-experimental | Generated an alert notification via SMS when patient had signs of active pulmonary tuberculosis, and compared time to response pre- and post-implementation. |

|

| Etchells | 2011 | Quasi-experimental | Generated alerts via SMS or pager for critical laboratory values with available decision support options via smartphone or hospital intranet. Examined pre- and post- implementation. |

|

| White | 1984 | RCT | A decision support system monitored multiple clinical signs of digoxin toxicity, including drug-drug interactions, laboratory data, and electrocardiographic findings. Alerts generated a printout placed in the patient’s chart. Compared alerts to no alerts. |

|

| Kuperman | 1999 | RCT | Alert notifications were generated for 12 identified critical laboratory values and delivered via hospital paging system. Randomized by patient to receive alert or not. |

|

| Etchells | 2010 | RCT | Alerts of critical laboratory values were sent to covering physician’s pager and compared to usual care with telephone calls. Randomized by lab result to generate alert or not. | Nonstatistically significant reduction in median response time to alerts 39.5 min vs 16 min (P = .33). |

Table 3.

Frequency of publications by decade

| Decade | Publications | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1980–1989 | 5 | 15 |

| 1990–1999 | 12 | 35 |

| 2000–2009 | 9 | 26 |

| 2010–2016 | 8 | 24 |

Alerts for critical laboratory results

Implementations

The primary purpose of most of the notification systems in our analysis is to generate automated alerts of critical laboratory values. The earliest systems identified in the literature were the Computerized Laboratory Alerting System (CLAS)6,29 and ALERT system18 at Latter Day Saints Hospital, and the ALERTS system developed at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.27

ALERT was first created to prompt physicians of potentially life-threating laboratory or pharmacy information, which generated alerts on bedside terminals.18 These reports were received by nurses, who would then call the responsible physician. Johnson et al. described the ALERT system and methods by which its effects were studied from a nursing perspective. They reported that 12.8% of all patients generated at least 1 alert during the study period. A survey of physicians found ALERT generally beneficial and justified, although 55% of nurses found it “always” or “sometimes” annoying.18

Similar to ALERT, CLAS was developed to monitor for life-threatening conditions and generate alerts on the nursing terminals. Bradshaw et al. reported an average time to acknowledgment of 38.7 h. To improve this, one hospital floor had a flashing light installed as a visual reminder. That floor’s time fell from 28 h to 6 min on average, with a 100% acknowledgment rate.29

The ALERTS system was designed to identify critical values, critical trends, and calculation-adjusted values in laboratory results.8,27 The number of alerts associated with a patient’s stay in the intensive care unit was found to be predictive of poor outcomes, with 9.5% mortality associated with alerts compared to 0% with no alerts.27

Flyn et al. used e-mail to alert providers of acute kidney injury with real-time monitoring of increasing creatinine levels. They confirmed portions of the alerts with manual review and found that 70% of alerts were due to acute kidney injury, identifying 61 new diagnoses of the condition.48

To address some of the portability and delivery limitations of terminal-based systems,6,10,12 Tate et al.12,32 used digital pagers. In a 1-week study, they discovered that only 60% of critical potassium values were reported to the nursing floor via telephone, and in an audit of 124 charts, 85% contained documentation of critical lab values but only 35% were reported.32 In their design, critical results generated a page to the nurse caring for the patient. Evaluation of this system reported 335 alerts in a 13-week period, with 100% acknowledgment at an average time of 38.6 min. Nurses found 92% of these alerts clinically appropriate, and alerts were the primary source of information for 67% of cases.12,32

Kuperman et al.10 published an alternative approach by presenting critical values to physicians with actionable interventions. After receiving a page, the physician could access a workstation or call hospital telecommunications and receive actionable items linked to the EHR. Over a 6-month period there were 1214 responses to 1730 alerts (70.2%). Actions followed 71.5% of these.10 In a later study, alert retraction and update notifications were added. Of these, 26% contained new information and only 0.4% were retracted, demonstrating that communicating modifications and updates is important.34

A caveat of pager notifications was the need for an up-to-date database of provider contact information. Parl et al. employed hospital operators. When an alert was not acknowledged within 10 min, the operator contacted the physician or nurse caring for the patient by phone. Median response time dropped from 10 to 3 min, with 95% acknowledgment.43

Wagner et al. examined alerts of critical values as well as positive microbiology cultures, where physicians acknowledged receipt with 2-way pagers. At the time of publication, 35 resident physicians were using the system and reported increased overall clinical work efficiency.13

Similarly, Shabot et al. implemented 2-way wireless functionality to monitor laboratory and physiologic data for 5 major events: critical values, critical trends, dynamically adjusted values (such as pH or PCO2 where alert limits were modified by additional variables), “exception conditions” (such as hypotension), and medication advisories. In a 6-month study, they demonstrated a total of 2935 alerts. They concluded that numerous clinical decisions were made using these, but impacts and outcomes were not studied.29,37

With many successful implementations of pager alerts, a next step was to utilize personal digital assistants or text messaging (SMS) to smartphones.36,47 Shabot et al.29,48 augmented their existing system to include personal digital assistant delivery, with alerts for 10.3% of patients over a 3-month study period.36

Lordache et al. used smartphones. The authors notified providers of critical results, with delivery by e-mail, fax, or SMS via their modality of choice. The authors concluded that cellphones were ideal for receiving critical alerts.38

Quasi-experimental studies

In a separate study, CLAS demonstrated, over 9 months, identification of 650 critical results, resulting in a 12% increase in appropriate care. The average time a patient spent in metabolic acidosis declined from 44.3 to 26.5 h, and mean length of stay decreased from 14.6 to 8.8 days.6

Paltiel et al. created a system with the specific role of identifying hypokalemia. Terminals would alert to indicate a patient’s critically low potassium. A 6-month pre-post implementation study demonstrated improvements in all outcomes, but were statistically significant only for normalization of hypokalemia (P = .02).31

Rind et al.17,34 examined e-mail alerts of rising creatinine. The authors performed a 3-month control, 6-month intervention and 3-month control time series,34 then additional 3-month intervention and control periods.17 Time to modification of doses of nephrotoxic and renally excreted medications decreased by an average of 21.6 h when any physician who viewed the chart within 3 days received an e-mail alert.17

Galanter et al.’s39 system generated synchronous alerts at the time of order entry, but also generated inbox and printout alerts for patients prescribed digoxin. In a 6-month study, they demonstrated that electrolyte supplementation improved, and for hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia, asynchronous notifications were more effective than synchronous.

When comparing text-message notifications to phone calls, Park et al.42 found that mean and median response times to critical serum potassium levels decreased by 40.8 and 65.0%, respectively. Similarly, text-message notifications at Padua Hospital reduced time to notification and rate of successful notification when compared to telephone notifications.45

A step-wedged randomized prospective study performed by Etchells et al. examined critical alerts on smartphones or pagers by comparing the ratio of completed clinical actions to all potential actions. There was no difference in the median proportion of clinical actions (50%) when the system was on or off, nor any statistically significant difference in rates of adverse events.47 Conversely, Chen et al.35 demonstrated that text-message alerts of testing for tuberculosis improved time to response and isolation of patients.

RCTs

In 1984, White et al. demonstrated with a double-blind RCT a 22% increase in actions performed by physicians receiving printed alerts of markers of digoxin toxicity.18,50 A 2.7-fold increase in checking digoxin levels and a 2.8-fold increase in holding digoxin were observed when comparing notifications to standard care.28

Kuperman et al.10 performed an RCT with their previously described system, comparing no alerts to pages. A decrease from 96 to 60 min in time to treatment for the intervention group was observed, but no difference in adverse events, which the authors attributed to insufficient power.35

Etchells et al. compared critical alerts to phone calls. Median response time was 16.0 min for the system and 39.5 min for phone calls. This was not statistically significant; however, the authors commented on the potential for bias, as 39.5 min was faster than many other times reported. Some of the alerts were viewed as nuisances, and there was difficulty with alert redirection upon transitions of care.16

Systematic reviews

A meta-analysis compared 4 publications on automated systems to 5 publications on call centers. Automated systems research included means as statistics and dichotomized values (percent effectively communicated) for call centers, therefore results were calculated differently. The authors used Cohen’s d for the automated systems (grand mean reduction in time) and found that 61.8% of the alerts were faster than standard reporting. The mean odds ratios for call centers was an improved time to result of 88.6%. They concluded that no recommendation could be made for automated systems, but that call centers were effective.47

Urgent notifications

Implementation studies

While the majority of alerting systems were designed to provide clinicians with rapid delivery of critical information, some attempted asynchronous delivery of urgent results to improve physician awareness.

Modai et al. displayed daily alerts on a patient’s computerized chart for abnormal or missing values. Resident physicians were questioned to assess awareness, with a total of 0.77 notifications per patient per day, but residents were aware of only half of these. Approximately 7% of notifications resulted in further testing, and clinical management changes occurred every 3 days. They concluded that even more results could have remained unnoticed without alerts.20

Dong et al.’s system monitored laboratory results returned after patients had been discharged from the emergency department. It generated ∼10–20 alerts per week via e-mail or web page, which were manually validated for confirmation.21

Field et al. developed a system within the Epic EHR (Epic Systems, Madison, WI, USA) with inbox notifications to providers with abnormal values that resulted during hospitalization.19 They constructed a “blueprint” for notifications, including discharge, scheduling, laboratory information, and new medication lists. The software generated messages, and an interface engine allowed delivery to appropriate individuals.

Quasi-experimental studies

Staes et al. evaluated notifications about serum creatinine and drug levels for liver transplant patients in the outpatient setting, finding some increases in workload but simplification of the identification and trending of abnormal values. There were significant decreases in some response times, and the positive predictive value that new information was contained in notifications increased from 46% to >99%.40

Similarly, Singh et al. attempted to improve follow-up of outpatient results with e-mail. They discovered that 10.2% of notifications were never acknowledged, and with delayed review, results indicating new diagnoses were less likely to be acknowledged when compared to a known diagnosis (odds ratio = 7.35). They concluded that safety concerns remain for automated notifications of results in the outpatient setting.44

Elective notifications

Implementation studies

While prompt responses to critical results are vital for medical management, clinician awareness of noncritical and normal reports can be of utility.50 Poon et al.15 allowed physicians to select results for notification regardless of the result value. At the time of order entry, clinicians could request notification of lab completion via page or e-mail, or forward results to another provider. In 1 year, 780 clinicians used the system, with a maximum of 2300 uses per month. Common normal value alerts included cardiac troponins and creatine kinase, with 57% reporting the highest level of reliability, and 79% and 89% reporting the highest level of ease of use and helpfulness, respectively.

Similarly, Chen et al.14 created a design for notifications of physiologic parameters and laboratory results in the intensive care unit. The authors created an integrated rule editor to allow customized alerts from e-mail, pager, and personal device. In a survey of medical staff, 95% reported that use of this platform was of “great help” in treating critically ill patients.14

Quality appraisal

This study attempts to provide a review of the available scientific literature on the subject of asynchronous automated electronic laboratory notifications. We examined >3000 titles to identify 34 articles meeting our inclusion criteria. Of these, only 3 (8.8%) described an RCT design, the gold standard in evaluating effectiveness of interventions.51 The differences in study designs makes comparison of these publications difficult.

The vast majority of evaluations were conducted in the United States and on systems that were locally developed prior to the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009,53 which spurred an increase in the acquisition and use of EHRs.53 The limited number of publications included in our results that have been integrated into a commercially available EHR limits the external validity of our findings.

DISCUSSION

This analysis demonstrates the abundant variability in the many asynchronous automated laboratory notification systems that have been successfully implemented over the last 4 decades. These publications are heterogeneous in design, clinical setting, and experimental methodology. This makes performing a meta-analysis or statistical comparison impossible, yet trends in results can allow inferences on the effect of these systems.

A number of publications on automated notifications have confirmed reductions in time to intervention, a high degree of clinician approval, and a beneficial impact on care quality.10,15,35,45 Other studies have demonstrated a lack of improvement or a reduction in adverse events,42 and still others have demonstrated continued safety concerns associated with automated notifications, even increased rates of adverse events.44,46 Yet in many instances, noteworthy clinical improvements have been demonstrated.6,10,12–15

The main alternative to automated systems is the traditional phone call. While some researchers recommended telecommunication,47 others showed a lack of efficacy of phone calls.54 Electronic notifications prompt quick response times from clinicians, and repeated checking for pending results causes frustration and inefficiency,15 hence the need for asynchronous notification systems.

Clinical information systems play an essential role in alerting health care providers of life-threatening situations.55 While humans struggle to cognitively process large volumes of laboratory results, computers handle such tasks easily. Automated notifications can save time and improve quality,12 with asynchronous outperforming synchronous notifications.31 While it is apparent that a variety of effective critical, urgent, and elective notifications can be generated, a number of questions for the future of this form of clinical alert remain: How are the correct alert criteria identified for notifications? How can the appropriate individual be notified effectively? How can these systems be integrated into modern EHRs?

The message

The majority of articles included in this analysis identified single critical laboratory values and generated alerts to clinicians.6,10,17,32,46,42,35 Some also identified clinically important trends (eg, a change at a concerning rate, while not necessarily passing a critical threshold)8,17,27 or calculation-adjusted notifications (values deemed critical only if appropriate criteria were met).27,36 Though some critical alerts are necessary, not all critical results warrant notification, because not all critically abnormal laboratory values require emergent intervention.8 However, some studies have demonstrated that noncritical urgent and elective notifications can also improve clinical care.14,15,19–21

Despite many of these studies demonstrating positive results, few recent articles have utilized modern HIT to create intelligent CDSSs. The “learning health system” is a key goal of the biomedical informatics community,56 yet advancements in clinical laboratory notification are notably lacking. Future notification systems could interpret and predict what notifications would be necessary and choose a modality of delivery appropriate for the acuity of that result. We propose research focusing on employing new techniques to create novel CDSSs.

The Recipient

A number of earlier studies notified nurses of critical results,18,32,43 due to their close proximity to the terminals where these alerts would display32; however, having to bear the responsibility of notifying the caring physicians resulted in dissatisfaction.18

With the advent of pagers, the role of notification recipient transitioned from nurse to physician.10,13,15,16,20,47 One concern of modern medical education is that the number of resident handoffs in care has increased, thus increasing adverse event risk.57,58 It is difficult to forward clinical alerts after transitions of care.34 While some systems employ hospital telecommunication after an alert failure,34 this solution defeats the purpose of an automated system. Integrating role-based scheduling systems into notification systems holds the potential to optimize successful delivery, but dictates reliance on up-to-date schedules and pager assignments. Further studies examining clinical notification delivery, including improved forwarding and subscription-based solutions, are needed. Appropriate methods of escalation should be examined to determine how to notify the responsible clinician without overwhelming nonessential team members. Additionally, while many studies utilized phones for verbal confirmation or 2-way pagers for acknowledgment of receipt of a notification,10,13,27,36 these processes use technology that can be tedious in a potentially emergent situation. Future research should examine improved methods of receipt acknowledgment utilizing modern technology as well as the role of improved actionable interventions associated with notifications.

Modalities, frequency, and timing

Our findings demonstrate the progress made over the last 4 decades in laboratory alerts. From the initial terminal alerts to advances using pagers and personal devices, the notification medium has changed with the technology of the time period. While many of these implementations demonstrate the use of innovative technology at the time of publication, the majority of studies included in our analysis were published before 2010. We expect that more modern technology developed in the current decade will allow for further improvements. Specifically, there is a question regarding the continued utilization of outdated pagers,59 previously considered the preferred method of notification.60 The time is ripe to transition to more advanced technology,59 and it is expected that cellphones and personal devices will replace pagers.14,37 Future research should further compare notifications on personal devices and other modalities, including how smartphone applications could improve patient care through actionable interventions.

It is accepted that HIT solutions can aid providers with the vast amounts of clinical data they receive.35 However, an additional concern about automated systems is increased alert fatigue resulting from constant push notifications.22 Though real-time alerts can improve clinical decision-making22 and are appreciated,35 unnecessary alerts can cause information overload.23

Studies have demonstrated that organized committees focusing on the number of alerts in a hospital can reduce their frequency.61 It may also be worth considering a strategy allowing notification of new results to be requested by the ordering physician. A subscription-based model could potentially improve care and prevent alert fatigue,15 though to our knowledge the effect of subscription-based alerts has not been studied in vendor systems. Subscription-based notifications could allow for improved quality of care associated with automated systems without the burdens of passive alerting systems.22 Future research should examine the ideal methods of notification and study technologies such as applications and wearables that demonstrate improvements in clinical workflow and quality of care.

Integration

Given that the majority of the studies included in this review were performed prior to the passing of the HITECH Act,52 we question why so few laboratory notification systems have been implemented and/or published since the advent of vendor-based EHRs. Despite demonstrating reductions in time to result review, there are no mentions of clinical laboratory result notifications in the Meaningful Use objectives, yet other forms of CDSS are required.62

It is unclear if such notification systems are not a priority for EHR vendors, are too difficult to implement, or are ignored, given continued reliance on phone calls. To answer these questions, we suggest that studies examine vendor-based notification systems. We would like to highlight the need for RCTs to assess the true downstream effect of notifications of laboratory results on patient outcomes. Additionally, optimal integration into the modern EHR should involve further opportunities for decision support and not just delivery of information. Options for clinical documentation, order entry, or contextually relevant reference information could further improve clinician workflow and possibly improve quality of care.

Though the effects of asynchronous automated electronic laboratory result notification systems have been demonstrated in the literature, there continue to be barriers to their adoption in modern EHRs. One potential solution is to design an analysis framework to demonstrate effects on clinical outcomes by rigorously evaluating the suggested research questions described herein. A formal methodology could allow invested parties to demonstrate improved workflow, health care costs, and quality of care to further advance the need for these important innovations.

LIMITATIONS

This review has a number of limitations, including the possible exclusion of relevant articles due to the search process. As notification system publications can span a number of relevant topics, including computer science, informatics, and clinical medicine, a wide net of search terms was utilized, resulting in a large number of results. Thus, a title review had to be conducted, which could have led to the exclusion of articles not identified by title. Additionally, it is possible that relevant literature is cited in non-biomedical databases that we did not search. The majority of experimental studies included in our analysis demonstrated positive results. Therefore, our findings suggest the possible existence of publication bias, a known phenomenon in the EHR literature.63 Lastly, we may have excluded relevant publications not written in English.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review presents several automated electronic notification systems for laboratory results that have been successfully implemented, many showing significant improvements in workflow or reduction in time to result review. Future research should investigate improving physician awareness of important laboratory results while preventing alert fatigue. Additionally, studies should be conducted to evaluate new methods of notification based on modern technologies.

Funding

BHS was supported during the drafting of this manuscript by the National Library of Medicine under award number T15 LM007079. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Library of Medicine.

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Contributors

Study conception and design were done by all authors. Acquisition of data was performed by BHS, with analysis performed by BHS, TAN, and DKV. Interpretation of the data was done by all authors, with study supervision provided by DKV. Drafting of the manuscript was performed by BHS, while critical revisions for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published were done by all authors. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- 1. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;244:378–86; quiz 87–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chopra V, McMahon LF Jr. Redesigning hospital alarms for patient safety: alarmed and potentially dangerous. JAMA. 2014;31112: 1199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schnall R, Liu N, Sperling J, Green R, Clark S, Vawdrey D. An electronic alert for HIV screening in the emergency department increases screening but not the diagnosis of HIV. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;51:299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Green RA, Hripcsak G, Salmasian H et al. Intercepting wrong-patient orders in a computerized provider order entry system. Annals Emerg Med. 2015;656:679–86 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evans RS, Johnson KV, Flint VB et al. Unit-wide notification of ventilator disconnections. Proc Annu AMIA Symp. 2005:951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tate KE, Gardner RM, Weaver LK. A computerized laboratory alerting system. MD Comput. 1990;75:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradshaw KE, Gardner RM, Clemmer TP, Orme JF, Thomas F, West BJ. Physician decision-making: evaluation of data used in a computerized ICU. Int J Clin Monit Comput. 1984;12:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shabot MM, LoBue M, Leyerle BJ, Dubin SB. Inferencing strategies for automated ALERTS on critically abnormal laboratory and blood gas data. Proc Ann Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1989:54–57. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Callen J, Georgiou A, Li J, Westbrook JI. The safety implications of missed test results for hospitalised patients: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;202:194–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuperman GJ, Teich JM, Bates DW et al. Detecting alerts, notifying the physician, and offering action items: a comprehensive alerting system. Proc Annu AMIA Fall Symp. 1996:704–08. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuperman GJ, Boyle D, Jha A et al. How promptly are inpatients treated for critical laboratory results? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;51:112–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tate KE, Gardner RM, Scherting K. Nurses, pagers, and patient-specific criteria: three keys to improved critical value reporting. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995:164–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wagner MM, Pankaskie M, Hogan W et al. Clinical event monitoring at the University of Pittsburgh. Proc Annu AMIA Fall Symp. 1997:188–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen HT, Ma WC, Liou DM. Design and implementation of a real-time clinical alerting system for intensive care unit. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:131–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Poon EG, Kuperman GJ, Fiskio J, Bates DW. Real-time notification of laboratory data requested by users through alphanumeric pagers. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;93:217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Etchells E, Adhikari NK, Cheung C et al. Real-time clinical alerting: effect of an automated paging system on response time to critical laboratory values – a randomised controlled trial. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;192:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rind DM, Safran C, Phillips RS et al. Effect of computer-based alerts on the treatment and outcomes of hospitalized patients. Arch Int Med. 1994;15413:1511–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson DS, Ranzenberger J, Herbert RD, Gardner RM, Clemmer TP. A computerized alert program for acutely ill patients. J Nurs Adm. 1980;106:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Field TS, Garber L, Gagne SJ et al. Technological resources and personnel costs required to implement an automated alert system for ambulatory physicians when patients are discharged from hospitals to home. Inform Prim Care. 2012;202:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Modai I, Sigler M. A computerized laboratory alerting system in a psychogeriatric unit. MD Comput. 1998;152:95–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong H, Greenes D, Fleisher G, Kohane I. An alert system for ED laboratory test results. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998:994–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reddy MC, McDonald DW, Pratt W, Shabot MM. Technology, work, and information flows: lessons from the implementation of a wireless alert pager system. J Biomed Inform. 2005;383:229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh H, Spitzmueller C, Petersen NJ, Sawhney MK, Sittig DF. Information overload and missed test results in electronic health record-based settings. JAMA Int Med. 2013;1738:702–04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Common Example Scenarios in FHIR 2015. https://www.hl7.org/fhir/usecases.html. Accessed March 16, 2017.

- 25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals Int Med. 2009;1514:264–69, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Int Med. 2009;1514:W65–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shabot MM, LoBue M, Leyerle BJ, Dubin SB. Decision support alerts for clinical laboratory and blood gas data. Int J Clin Monit Comput. 1990;71:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. White KS, Lindsay A, Pryor TA, Brown WF, Walsh K. Application of a computerized medical decision-making process to the problem of digoxin intoxication. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984;43:571–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bradshaw KE, Gardner RM, Pryor TA. Development of a computerized laboratory alerting system. Comput Biomed Res. 1989;226:575–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inferencing Strategies for Automated ALERTS on Critically Abnormal Laboratory and Blood Gas Data. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2245759/. Accessed March 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rind DM, Safran C, Phillips RS et al. The effect of computer-based reminders on the management of hospitalized patients with worsening renal function. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1991:28–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tate KE, Gardner RM. Computers, quality, and the clinical laboratory: a look at critical value reporting. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1993:193–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shabot MM, LoBue M. Real-time wireless decision support alerts on a Palmtop PDA. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995:174–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuperman GJ, Hiltz FL, Teich JM. Advanced alerting features: displaying new relevant data and retracting alerts. Proc Annu Fall AMIA Symp. 1997:243–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kuperman GJ, Teich JM, Tanasijevic MJ et al. Improving response to critical laboratory results with automation: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;66:512–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shabot MM, LoBue M, Chen J. Wireless clinical alerts for physiologic, laboratory and medication data. Proc AMIA Symp. 2000:789–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iordache SD, Orso D, Zelingher J. A comprehensive computerized critical laboratory results alerting system for ambulatory and hospitalized patients. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001;84(Pt 1):469–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paltiel O, Gordon L, Berg D, Israeli A. Effect of a computerized alert on the management of hypokalemia in hospitalized patients. Arch Int Med 2003;1632:200–04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Galanter WL, Polikaitis A, DiDomenico RJ. A trial of automated safety alerts for inpatient digoxin use with computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;114:270–07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Staes CJ, Evans RS, Rocha BH et al. Computerized alerts improve outpatient laboratory monitoring of transplant patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;153:324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park HI, Min WK, Lee W et al. Evaluating the short message service alerting system for critical value notification via PDA telephones. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;382:149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Piva E, Sciacovelli L, Zaninotto M, Laposata M, Plebani M. Evaluation of effectiveness of a computerized notification system for reporting critical values. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;1313:432–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Parl FF, O’Leary MF, Kaiser AB, Paulett JM, Statnikova K, Shultz EK. Implementation of a closed-loop reporting system for critical values and clinical communication in compliance with goals of the joint commission. Clin Chem. 2010;563:417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Sittig DF et al. Notification of abnormal lab test results in an electronic medical record: do any safety concerns remain? Am J Med. 2010;1233:238–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen TC, Lin WR, Lu PL et al. Computer laboratory notification system via short message service to reduce health care delays in management of tuberculosis in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. 2011;395:426–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Etchells E, Adhikari NK, Wu R et al. Real-time automated paging and decision support for critical laboratory abnormalities. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;2011:924–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liebow EB, Derzon JH, Fontanesi J et al. Effectiveness of automated notification and customer service call centers for timely and accurate reporting of critical values: a laboratory medicine best practices systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. 2012;45(13–14):979–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Flynn N, Dawnay A. A simple electronic alert for acute kidney injury. Ann Clin Biochem. 2015;52(Pt 2):206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pryor TA, Gardner RM, Clayton PD, Warner HR. The HELP system. J Med Sys. 1983;72:87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hogan WR, Wagner MM. Optimal use of communication channels in clinical event monitoring. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998:617–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. D’Agostino RB, Kwan H. Measuring effectiveness. What to expect without a randomized control group. Med Care. 1995;33(4 Suppl):AS95–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. HealthIT.gov. Health IT Legislation and Regulations. 2016. https://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/health-it-legislation. Accessed March 16, 2017.

- 53. Wright A, Henkin S, Feblowitz J, McCoy AB, Bates DW, Sittig DF. Early results of the meaningful use program for electronic health records. New Engl J Med. 2013;3688:779–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Howanitz PJ, Steindel SJ, Heard NV. Laboratory critical values policies and procedures: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes Study in 623 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;1266: 663–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shabot MM, Gardner RM. Decision Support Systems in Critical Care. Springer Science & Business Media; 1994:143–73. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Roberts K, Boland MR, Pruinelli L et al. Biomedical informatics advancing the national health agenda: the AMIA 2015 year-in-review in clinical and consumer informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(e1):e185–e190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Okie S. An elusive balance: residents’ work hours and the continuity of care. New Engl J Med. 2007;35626:2665–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Riesenberg LA. Shift-to-shift handoff research: where do we go from here? J Graduate Med Educ. 2012;41:4–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Carlile N, Rhatigan JJ, Bates DW. Why do we still page each other? Examining the frequency, types and senders of pages in academic medical services. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;261:24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wagner MM, Eisenstadt SA, Hogan WR, Pankaskie MC. Preferences of interns and residents for E-mail, paging, or traditional methods for the delivery of different types of clinical information. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998:140–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kuperman GJ, Diamente R, Khatu V et al. Managing the alert process at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Proc AMIA Annu Symp. 2005:415–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. HealthIT.gov. Meaningful Use Definition & Objectives. 2015. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives. Accessed March 16, 2017.

- 63. Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. Publication bias in clinical trials of electronic health records. J Biomed Inform. 2013;461:139–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]