Abstract

Purpose of review:

Information on potential risk factors and clinical correlates of compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) may help inform more effective prevention and treatment measures. Sexual victimization, specifically, child sexual abuse (CSA), has been associated with CSB.

Recent findings:

This systematic review describes 21 studies on the relationship between CSA and CSB. Most studies identified a significant association between CSA and CSB. However, variability in measurements, potential differences in links among community versus clinical samples, relevance of research among college samples, lack of support for gender-related differences, and the need for more longitudinal designs were identified.

Summary:

Research would benefit from more formalized assessments of CSB across different populations. Prevention efforts should be aimed toward individuals who experienced CSA and/or other abuse, particularly if they report engaging in risky sexual behavior. Individuals with CSB who have experienced sexual abuse may benefit from trauma-focused treatment.

Keywords: compulsive sexual behavior, child sexual abuse

INTRODUCTION

Compulsive sexual behavior (CSB; also termed sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity, hypersexuality, out-of-control sexual behavior, problematic sexual behavior, or sexual addiction) consists of persistent failure to control intense, recurrent sexual impulses or urges, resulting in repetitive sexual behavior over an extended period that generates marked distress or impairment in functioning (Kraus et al., 2018). The sexual behaviors may be considered “socially acceptable”, or “normophilic”, including masturbation, pornography use, and sex with multiple anonymous partners, but they are typically extreme in frequency and/or intensity in a manner leading to distress or interference with personal, interpersonal, or vocational pursuits (Kuzma & Black, 2008). When the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2018) was officially adopted at the World Health Assembly in May 2019, Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) was included and classified as an impulse-control disorder. This recognition is an important first step for furthering discussion of compulsive/problematic sexual behaviors/disorders. Nevertheless, questions remain regarding appropriate categorization of the disorder, as it shares many underlying features with addiction (Kowalewska et al., 2018; Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016; Stark, Klucken, Potenza, Brand, & Strahler, 2018). Estimates of CSB have been reported to range from approximately 3–6% of U.S. adults (Garcia & Thibaut, 2010), including 3% of men and 1% of women (Odlaug et al., 2013). However, “clinically relevant levels of distress and/or impairment associated with difficulty controlling sexual feelings, urges, and behaviors” was estimated at 8.6% (10.3% of men and 7.0% of women) in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults (Dickenson, Gleason, Coleman, & Miner, 2018). In a separate nationally representative U.S. adult sample, sexual impulsivity was acknowledged by 14.7% of individuals (18.9% of men and 10.9% of women; Erez, Pilver, & Potenza, 2014). As such, precise rates of CSB remain unclear (Kraus et al., 2016), partly due to differences in criteria and measurement (Womack, Hook, Ramos, Davis, & Penberthy, 2013). CSB is associated with a range of problematic behaviors and outcomes, including risky sexual behaviors, unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and experiencing nonsexual attacks or robberies (Chemezov, Petrova, & Kraus, 2019; Griffee et al., 2012; Kalichman & Cain, 2004; Schneider & Irons, 2001).

Greater knowledge of risk factors and clinical correlates of CSB can help develop more effective prevention and treatment interventions. Sexual victimization, specifically, child sexual abuse (CSA), affecting approximately 17% of girls and 8% of boys (Putnam, 2003) has been implicated as one of many potential precursors to CSB (Kafka, 2010; Kuzma & Black, 2008). The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Center for Disease Control (CDC) each provide definitions of CSA that includes direct contact with a child as well as noncontact sexual abuse that may include exploitation, sexual harassment, exposing a child to pornography, and filming or photographing a child in a sexual manner (Leeb, Paulozzi, Melanson, Simon, & Arias, 2008; World Health Organization, 1999). CSA is a widespread public health problem (Murray, Nguyen, Cohen, 2014) and population-level estimates indicate that one in ten children will experience sexual abuse before the age of 18 years (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2014; Townsend & Rheingold, 2013). CSA has been linked with many deleterious health outcomes, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide, homelessness, impaired functioning, and revictimization in adulthood (Courtois, 2004; Greene, Neria, & Gross, 2016; Walsh, Blaustein, Knight, Spinazzola, & van der Kolk, 2007). Sexual abuse is also associated with multiple other negative outcomes related to sexuality, including an increased risk of sexual perpetration (Lisak & Beszterczey, 2007), as well as shame, guilt and anxiety during sexual arousal, decreased sexual desire, dissociation, and orgasm and arousal disorders among men and women (Lisak & Beszterczey, 2007; Loeb, Williams, Vargas, Wyatt, & O’Brien, 2002; Najman, Dunne, Purdie, Boyle, & Coxeter, 2005; Price, 2007; Walker et al., 1999) Additionally, two major pathways commonly linked to CSA, sexual avoidance and sexual compulsivity (Aaron, 2012; Colangelo & Keefe-Cooperman, 2015), may co-occur, leading to a type of sexual ambivalence (Noll, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015), and these domains may be differentially prominent over the course of one’s life (Herman & Hirschman, 1981).

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the relationship between CSA and later CSB. Neurologically, early sexual victimization may “blunt” the right hemisphere of the brain, impairing insight, emotion regulation, and ability for interpersonal connection, all characteristics associated with CSB (Katehakis, 2009). The traumagenic dynamics model (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985) asserts that survivors of CSA may develop problematic “sexual scripts” that shape their beliefs and guide their decisions regarding sexual behaviors, influencing subsequent risky sexual behavior (Castro, Ibáñez, Maté, Esteban, and Barrada, 2019). Attachment theories based on the ideas of Bowlby (1969) and Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall (1978) posit that individuals develop internal working models from early experience with caretakers that are encoded into their concept of self (Alexander, 2005) and lead to introjection (Sullivan, 1954). Other theorists have suggested that sex might be used as a means of attempting to take back control lost in childhood due to sexual abuse (Gold & Heffner, 1998). In addition, some research suggests that a substantial minority of CSA survivors may engage in frequent sexual encounters as a means of regulating their distress and coping with trauma-related symptoms (Stappenbeck et al., 2016).

Some of the earliest works examining links between CSA and CSB are reports of sexual victimization among individuals in treatment for sexual addiction. For instance, Carnes (1991) found that 39% of men and 63% of women in treatment for sexual addiction reported CSA in comparison to 8% of male and 20% of female healthy controls. Carnes & Delmonico (1996) found that among 290 men and women in treatment for sexual addiction, 78% reported CSA. Descriptive data on 19 men and 21 women seeking treatment in an outpatient psychiatric clinic for problematic cybersex involvement found that 57.9% of men and 76.2% of women reported CSA (Schwartz & Southern, 2000). Importantly, research on CSB samples has also described other types of maltreatment (e.g., physical and emotional abuse, neglect) that commonly occur alongside CSA. Ferree (2002) found that 81% of men and women in treatment for sexual addiction in their sample reported CSA, 72% physical abuse, and 97% emotional abuse. These other forms of abuse have also been linked with negative long-term health outcomes, including sexual difficulties (Meston, Heiman, & Trapnell, 1999; Schloredt & Heiman, 2003). The combination of multiple forms of abuse in childhood may predict CSB, rather than CSA alone (Meston et al., 1999; Schloredt & Heiman, 2003). Thus, in examining the relationship between CSA and CSB, it is critical to assess for other types of co-occurring maltreatment.

METHOD

Search Strategy and Study Selection

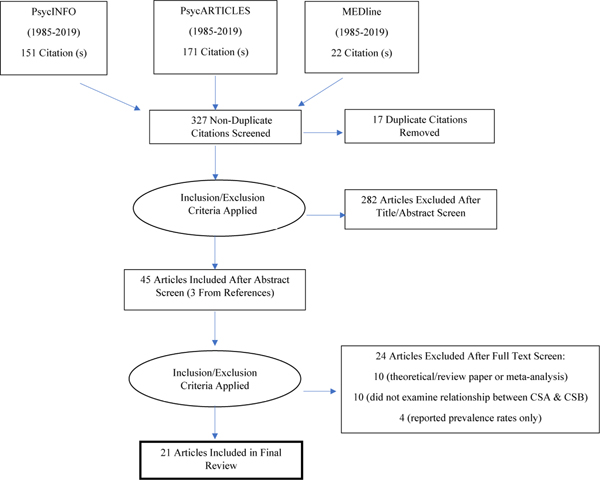

This systematic literature review examined studies that assessed the relationship between sexual abuse and CSB. First, we queried electronic databases (PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES and MEDLINE) for peer-reviewed journal articles published between January 1, 1985, and June 30, 2019. Search terms consisted of the following combinations of keywords “(“sex* abuse” OR “sex* trauma” OR sex* assault) AND (“sex* addiction” OR “hypersexuality” OR “compulsive sex*” OR “sex* preoccupation”).” In Figure 1, we present the study identification and selection process including abstract and full review of identified studies. Articles were excluded if they were in a language other than English, or a meta-analysis, systematic review, or theoretical paper. Additionally, articles were excluded if they only provided prevalence estimates, but did not perform analyses to determine statistical significance of associations between CSA and CSB. Lastly, we excluded papers that focused on the relationship between CSA and risky sexual behaviors that did not include a measure of sexual preoccupation. Studies met inclusion criteria if they examined the relationship between CSA and CSB, were an empirical study, and included measures of both CSA and CSB. Following full-text reviews by the first author, key data elements were extracted from studies included in the final review. These elements included details about study design, population, sample size, CSB and sexual victimization measures, and relevant findings. Twenty-one studies were included and used in identifying patterns across publications and gaps of knowledge worthy of further investigation to best inform prevention and treatment efforts relating to CSB.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews Flow Diagram (PRISMA) Flow Diagram

RESULTS

Overview of Studies

Table 1 includes a summary of data reviewed and descriptions of individual studies. Most (15) studies employed a cross-sectional survey design. Other designs included four cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal data, one cross-sectional case-control study, and one longitudinal design. Nine studies involved only males, four involved only females, and eight included both males and females. Two samples included adolescents and the others consisted of adults. No samples overlapped. Sample sizes ranged from 80 to 2,450 participants. The most commonly used CSB measure was the Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS; Kalichman & Rompa, 1995), which was used in seven studies, followed by the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST; Carnes, 1989), used in three studies. CSA was defined and assessed in multiple ways with ages ranging from before age 12 to before age 18. Among the 21 studies, 17 supported some form of relationship between CSA and CSB. In the four studies that did not support a significant relationship, specific aspects appeared related (e.g., CSB related to other types of abuse or CSA related to impulsive behaviors in general).

Table 1.

Summary of Study Characteristics and Findings

| First Author, Year | Study Design | Study Population | Sample Size | CSB Measure | Sexual Trauma Measure | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blain et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional interview and survey | Gay and bisexual men reporting CSB symptoms in NYC area | 182 men | CSBI1 | CTQ2: CSA subscale assessing unwanted touching to more severe forms of sexual abuse before age 18 | Men who endorsed CSA reported significantly higher CSB than those who denied CSA. CSA severity statistically predicted CSB above child physical and emotional abuse, depression, anxiety, and PTSD. |

| Chatzittofis et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional case control | Male patients with hypersexual disorder (HD) and healthy male volunteers | 107 men (67 patients and 40 healthy volunteers) | Patients met four or more of five of Kafka’s3 proposed diagnostic criteria | CTQ-SF4 (Swedish version5): CSA subscale | Patients who met criteria for HD did not endorse higher scores on CSA subscale compared to healthy volunteers, although they did endorse higher CTQ scores in general. HD patients with (versus without) suicide attempts reported higher scores on the CSA subscale. |

| Davis et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional survey | Male juveniles who had sexually offended sampled from inpatient treatment centers | 307 juvenile males | Three scales derived for current study to estimate latent trait of “normophilic excessive sexualization”: hypersexuality, sexual compulsivity, and sexual preoccupation | Four scales to assess CSA severity before age 17: number of sexual abusers, frequency of sexual abuse, degree of penetration, and degree of force | CSA and male caregiver psychological abuse were significantly associated with “normophilic excessive sexualization.” |

| Estévez et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional survey | Spanish women who had suffered CSA mostly referred by associations for treatment of childhood abuse and maltreatment | 182 women | MULTICAGE CAD-46 | CTQ-SF3 (Spanish version7) | CSA was not significantly correlated with sexual addiction, although it was related to impulsive behaviors in general. |

| Griffee et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional survey | Female undergraduate and graduate college students in addition to university faculty and staff and individuals from the same general population | 1502 women | Hypersexuality and Risky Sexual Behavior Scale (created for current study) | 16 statistical predictors involving sexual behaviors coerced by male partners and 14 predictors involving sexual behaviors coerced by female partners -Excluded women who endorsed father-daughter incest | Mean scores for Hypersexuality and Risky Sexual Behavior Scale and both of its subscales were significantly higher among those with CSA than those without. However, none of the 30 CSA items were among most powerful of 101 developmental statistical predictors of CSB. |

| Kingston et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional survey | Adult male sexual offenders who were either incarcerated or committed to treatment at time of assessment | 529 men | Three scales derived for current study to measure latent trait of hypersexuality: sexual compulsivity, sexual preoccupation, and sexual drive. | Assessed sexual abuse before age 17 by degree of penetration, amount of force, frequency, and exposure to pornography prior to age 13 | Significant correlations between different types of CSA and hypersexuality. Dose-response relationship between cumulative effects of sexual, emotional, physical abuse, and neglect with hypersexuality. |

| Långström et al., 2006 | Cross-sectional survey and interviews | Swedish adult men and women from a 1996 national survey of sexuality and health in Sweden | 2,450 adults (1,279 men, 1,171 women) | Upper 10% of population on sexual behaviors including number of sexual partners, frequency of pornography use, masturbation, etc. | 1 item: “Were you ever involved in a sexual activity without wanting it yourself?” Separate variable if abuse happened before age 18 | Sexual abuse both before and after age 18 differentiated between low and high hypersexuality groups for women, with sexual abuse associated with high hypersexuality. Only sexual abuse after 18 differentiated between these groups for men. |

| Marshall et al., 2006 | Cross-sectional survey | Adult men incarcerated for sexual offenses compared to community comparisons in Canada | 80 men (40 incarcerated men and 40 community men) | SAST8 | 1 item from SAST8: Were you sexually abused as a child or adolescent? | Participants with scores indicating sexual addiction across groups did not significantly differ in CSA. Incarcerated men with sex addiction were more likely to have experienced CSA than non-incarcerated men. |

| McPherson et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional survey | Adult users of support websites relating to drug, alcohol, gambling, and sexual addictions | 348 adults (195 women, 153 men) | SCS9 | ETISF10 SA subscale assessing unwanted touching to forced sex before age 18. Five additional items assessing exposure to sexual material before age 18 | CSA did not correlate with CSB, although childhood emotional abuse, youth exposure to pornography, and parental sex addiction were statistical predictors. |

| Meyer et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional survey | Geographically diverse U.S. adults | 812 adults (504 women, 308 men) | SAST8 | 1 item: “Before the age of 18, were you sexually abused?” | CSA, attachment anxiety, and emotion regulation were statistical predictors of CSB. |

| Noll et al., 2003 | 10-year prospective study of survey data | Girls with history of SA between ages 6–16, compared to non-abused girls of same age group and assessed 10 years later | 166 girls (77 girls with SA history and 89 non-abuse comparisons) | Scale derived for current study: SAAQ11: sexual preoccupation subscale | Child Protective Services substantiated report of sexual abuse by a family member involving genital contact/penetration before age 16 | Women who endorsed CSA 10 years earlier were more preoccupied with sex, younger at first voluntary intercourse, and, more likely to have been teen mothers than comparison participants, adjusting for mental health and demographics. Less severe forms of abuse associated with higher sexual preoccupation. |

| Opitz et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional survey | Women with self-identified sexual addiction; 56.6% of whom participated in a treatment program for sexual addiction | 99 women | W-SAST12 | CTQ2 | Although there was a significant positive correlation between sex addiction and CSA, only depression, family adaptability, and drug abuse statistically predicted sexual addiction in a regression analysis. |

| Parsons et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional survey | Men who have sex with men (MSM) in New York city taken from the Sex and Love study | 669 men | SCS9 | Two items assessing if participants reported ever been forced or frightened by someone into doing something sexually before age 16 or with partner at least 10 years older | Men with CSB were 2.2 times as likely as other men to have experienced CSA. Among MSM with high levels of polydrug use, depression, and partner violence, CSA did not relate to CSB. |

| Parsons et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional analysis of longitudinal cohort survey and interview data | “Highly sexually active” gay and bisexual men in NYC taken from the Pillow Talk study | 368 men | SCS9HDSI13 | See Parsons, 2012 requirement | Participants were organized into three groups—negative on both SCS and HDSI, positive on the SCS only, and positive on both. Although there was a trend for greater CSA among both SCS and HDSI than neither, the groups did not significantly differ. |

| Parsons et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional analysis of longitudinal cohort survey data | HIV-negative gay and bisexual men from the One Thousand Strong cohort | 1071 men | SCS9 | See Parsons, 2012 requirement | Adjusting for demographics and partner violence, polydrug use and depression, CSA was associated with 1.87 times the odds of reporting CSB. |

| Perera et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional survey | College students | 539 adults (166 men and 373 women) | SCS9Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale14 | 4-item scale by Aalsma et al.15 examining severity of CSA before age 12 | CSA and poor family environmental conditions statistically predicted CSB and sexual sensation-seeking, with CSA explaining the most variance for both. |

| Plant et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional survey and interview | UK men and women drawn from the GENACIS16 interview schedule | 2,027 adults (1,052 women, 975 men) | 1 item: “During the last 12 months has sexual activity interfered with your everyday life?” | 3 items taken from GENASIS16 assessing CSA before age 16 | CSA was significantly associated with problematic sexual activity in both men and women. |

| Skegg et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional analysis of longitudinal cohort survey data | Men and women (aged 32) in New Zealand from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study | 940 adults (474 men and 466 women) | 1 item: “In the past 12 months, have you had sexual fantasies, urges or behavior that you felt were out of control?” | 1 item: “Before you turned 16, did someone touch your genitals when you didn’t want them to?” | Men who defined their sexual behavior as “out of control” were significantly more likely than those who denied these behaviors to endorse CSA queried 6 years earlier (23% versus 6.1%). There was no significant difference among females. |

| Smith et al., 2014 | Longitudinal interviews at baseline, 3, and 6 months | Male Veterans of Operations Iraqi Freedom, Enduring Freedom, or New Dawn | 258 men | CSB portion (2 items) from MIDI17 | Single item at baseline taken from the DRRI18 assessing unwanted sexual activity before age 18 | Individuals with a history of CSA had more than 3 times greater odds of CSB than did those without such trauma, adjusting for other childhood abuse and mental health factors. |

| Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional survey | French-Canadian adults currently involved in a close relationship | 686 adults (529 women, 157 men) | French version of the SCS9 | 12-item measure to determine CSA before age 16. Severity determined by chronicity, type of act, relationship with perpetrator | For both men and women, CSA was positively associated with sexual compulsivity and sexual avoidance. |

| Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional survey | French-speaking Canadian adults from the community and universities | 1033 adults (760 women, 273 men) | French version of the SCS9 | 10-item measure to determine CSA before age 16. Specifiers: with or without presence of physical force or violence, and with or without “consent” of child | CSA severity was associated with higher sexual compulsivity in single individuals, higher sexual avoidance and compulsivity in cohabiting individuals, and sexual avoidance in married individuals. |

Note.

Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI), Coleman, Miner, Ohlerking, & Raymond, 2001

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Bernstein & Fink, 1998

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire- Short Form (CTQ-SF), Bernstein et al., 2003

MULTICAGE CAD-4, Pedrero Pérez et al., 2007

Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST), Carnes, 1989

Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS), Kalichman & Rompa, 1995

Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form (ETISF), Bremner, Bolus, & Mayer, 2007

Sexual Activities and Attitudes Questionnaire (SAAQ), Noll, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003

Women’s Sexual Addiction Screening Test (W-SAST), Carnes & O’Hara, 1994

Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI), Kafka, 2010

Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale, Kalichman et al., 1994

Gender, Alcohol and Culture: An International Study, World Health Organization, 2003

Minnesota Impulsive Disorder Inventory (MIDI), Grant, 2008

Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI), King, King, Vogt, Knight, & Samper, 2006.

Variation in Samples

Studies included in this review involved participants from several distinct populations. Six studies examined general community participants (Långström & Hanson, 2006; Meyer, Cohn, Robinson, Muse, & Hughes, 2017; Plant, Plant, & Miller, 2005; Skegg, Nada-Raja, Dickson, & Paul, 2010; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2016), four involved men who have sex with men (MSM; Blain, Muench, Morgenstern, & Parsons, 2012; Parsons, Grov, & Golub, 2012; Parsons et al., 2017; Parsons, Rendina, Moody, Ventuneac, & Grov, 2015), three examined incarcerated individuals who committed sexual offenses (Davis & Knight, 2019; Kingston, Graham, & Knight, 2017; Marshall & Marshall, 2006), three investigated individuals in treatment or seeking treatment for CSB and/or other addictions (Chatzittofis et al., 2017; McPherson, Clayton, Wood, Hiskey, & Andrews, 2013; Opitz, Tsytsarev, & Froh, 2009), two involved individuals with sexual trauma (Estévez, Ozerinjauregi, Herrero-Fernández, & Jauregui, 2019; Noll et al., 2003), two involved mostly university students (Griffee et al., 2012; Perera, Reece, Monahan, Billingham, & Finn, 2009), and one examined U.S. military Veterans (Smith et al., 2014).

Among the seven studies examining community samples, all contained both men and women and each supported a relationship between CSA and CSB. Two community studies indicated differential relationships among the groups compared. For instance, Langstrom (2006) found a relationship between CSA and hypersexuality for women but not for men. Vaillancourt-Morel (2016) found that CSA severity predicted CSB in single individuals, CSB and sexual avoidance in cohabitating individuals, and sexual avoidance in married individuals. Among four studies examining MSM, all but one found a statistically significant relationship between CSA and CSB (Parsons, Rendina, Moody, Ventuneac, & Grov, 2015). Parsons et al. (2015) organized participants into three groups—negative on two CSB scales, positive on one, and positive on both. Although there was a trend for CSA history among individuals positive on both scales than neither, the groups did not significantly differ.

The three studies investigating incarcerated individuals who committed sexual offenses involved samples consisting only of males, and one focused on juvenile participants. All indicated some form of a significant relationship between CSA and CSB, and one study indicated a group difference. Marshall (2006) found participants with scores indicating sexual addiction across groups did not significantly differ in CSA history. Nevertheless, incarcerated individuals with sexual addiction were significantly more likely to have experienced CSA than non-incarcerated counterparts. Among the three studies of individuals in treatment or seeking treatment for CSB and/or other addictions, one involved all men, one all women, and one contained both sexes. The study of women (Opitz et al., 2009) found a significant correlation between CSA and CSB, but other variables better accounted for CSB. The two other studies did not support a significant correlation between CSA and CSB, although there were links between CSB and other forms of abuse and negative family dynamics. Among the two studies on individuals with sexual trauma, both focused on women, including one sample that queried sexual abuse among children and adolescents. The study of adults did not support a significant relationship, although CSA was linked to impulsive behaviors in general (Estévez et al., 2019). Among the two studies of mostly students, one sample involved all women, and the other involved both men and women. Both found a significant link between CSA and CSB. Lastly, the veteran sample consisted of all men and found a significant association between CSA and CSB (Smith et al., 2014).

Variability in Measurement

The 21 studies varied in measurements of CSA and CSB. Definitions of CSA included contact and sometimes non-contact sexual incidents using a range of age cut-points from below age 18 (Blain, Muench, Morgenstern, & Parsons, 2012; Långström & Hanson, 2006; Meyer, Cohn, Robinson, Muse, & Hughes, 2017) to below age 12 (Perera et al., 2009). Additionally, there were different versions of the word “contact”, with some researchers defining only genital contact as CSA (Skegg et al., 2010). Some studies examined CSA as dichotomous and did not define the term specifically where others examined severity of CSA by variables such as chronicity, characteristics of the abuse, and relationship to the perpetrator. Lastly, some findings indicate inclusion of a broader range of early sexual experiences that may influence the development of problematic sexual behaviors, including early exposure to pornography (McPherson et al., 2013).

There were also differences in measurement of CSB (see Table 1). Several studies used multiple scales (either previously existing or created specifically for the study) to ensure measurement of different aspects of CSB. Some research examined CSB on a spectrum, while others examined it as dichotomous variable determined by whether individuals met a certain score on a given scale. Among the seven community samples, one study emphasized the frequency of sexual behavior (Långström & Hanson, 2006) while others assessed self-reported dyscontrol (Skegg et al., 2010) or interference with life activities (Plant et al., 2005). Among the three studies of individuals seeking treatment for CSB, one (Chatzittofis et al., 2017) examined hypersexual disorder according to Kafka’s (2010) proposed diagnostic criteria.

DISCUSSION

This review synthesized and described research related to the relationship between CSA and CSB. To our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis has focused exclusively on this association. Our goals were to review study designs, measures, samples, analyses, and findings to assess patterns and gaps of knowledge. We aimed to inform future research and foster insight into prevention and treatment of CSB. We found that most studies supported a relationship between CSA and CSB, though additional research including more diverse samples (e.g., women, ethnic and sexual minorities) are needed to fully examine these associations. Nevertheless, in some studies, other potential risk factors including different types of childhood maltreatment accounted for more variance in CSB or had a cumulative impact on CSB along with CSA. The findings establishing a link between CSA and CSB are consistent with studies indicating positive relationships between CSA and risky sexual behaviors (Abajobir, Kisely, Maravilla, Williams, & Najman, 2017; Homma, Wang, Saewyc, & Kishor, 2012). Additionally, a 2018 meta-analysis of MSM examining CSA and other factors as syndemic predictors of sexual compulsivity found a statistically significant small effect size between CSA and CSB (Rooney, Tulloch, & Blashill, 2018). The following discussion will focus on pertinent topics noted when reviewing these 21 studies: potential differences in links between CSA and CSB among community versus clinical samples and factors that may influence such differences, relevance of research among college samples, lack of support for biological sex or gender-related differences in the relationships between CSA and CSB, and the need for more longitudinal research.

In this review, most research was conducted on community samples (7), and these studies supported some form of relationship between CSA and CSB. Only three of the studies examined individuals in treatment or seeking treatment for CSB and/or other addictions. As stated above, two of these studies did not find a significant association, and one found a correlation, but it was better accounted for by other variables. Due to the scarce amount of research on this topic and differences across designs and measures, it is difficult to compare clinical and community samples. These findings suggest the importance of considering factors that may account for more of the variance in predicting CSB among clinical populations, such as co-occurring abuse, psychopathology, stress responsiveness, emotional regulation, and behavioral control, among others. Additionally, future research should ensure that CSB is assessed comprehensively, by examining ICD-11 inclusionary criteria (including distress or impairment) and how they relate to sexual behaviors. Research that merely examines distress or perceived dyscontrol associated with sexual behavior may not actually be assessing CSB, in that individuals, particularly those who have experienced CSA, may have a negative sexual self-concept (Lacelle, Hébert, Lavoie, Vitaro, & Tremblay, 2012) that may influence their perceptions of their sexual behavior. For instance, in a study of 383 college women (Fromuth, 1986), a history of CSA was associated with women describing themselves as “promiscuous.” Nevertheless, there was no relationship between CSA and age of first (consensual) sexual intercourse, frequency of sexual behavior, number of consensual partners, or sexual desires. In another community sample of 669 MSM in New York City, men reporting sexual compulsivity were twice as likely as other men to have experienced CSA (Parsons et al., 2012). Interestingly though, individuals who reported CSA did not have differences in the number of sexual partners in the last 90 days compared to non-abused counterparts. Thus, individuals with CSA may reported higher distress and impairment, although their actual sexual behavior may be similar to those who denied CSA. However, aspects of the sexual encounters (e.g., the extent to which the encounters may have involved blatant or nuanced boundary violations) warrant consideration in these relationships. Having an accurate conceptualization of the frequency of sexual behavior, in addition to distress, clinical impairment and other factors associated with it, could allow for more targeted treatment approaches. For instance, individuals with a negative sexual self-concept may benefit from interventions focused on building self-esteem, a positive sexual self-schema, greater body awareness and connection, or assertiveness rather than managing urges associated with CSB (Badgley, R., Allard, H., McCormick, N., 1984; Carvalheira, Price, & Neves, 2017; Rellini & Meston, 2011).

Additionally, only two studies focused on college students. A larger body of work has examined relationships between CSA and risky sexual behaviors among this population (e.g., Fromuth, 1986; Krahé & Berger, 2017; Meston et al., 1999). For instance, Meston, Heiman, & Trapnell (1999) found that among 1032 undergraduate students, after adjusting for physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and demographic variables, frequency of sexual abuse among young women was positively related to more permissive sexual attitudes and fantasies, frequency of masturbation, unrestricted sexual behavior, and frequency of intercourse. Because college students may be at elevated risk for developing sexual problems due to easy access to multiple sexual partners and openness to various sexual experiences (Dodge, Reece, Cole, & Sandfort, 2004), prevention efforts should be aimed toward students with CSA histories reporting risky sexual behaviors or CSB, including problematic pornography use.

Third, significant findings in this review did not appear to be influenced by an individual’s biological sex or self-reported gender. In the two studies that did indicate gende-rrelated differences, one found that CSA predicted hypersexuality only in women (Långström & Hanson, 2006) and the other only in men (Skegg et al., 2010). Some researchers have postulated that gender-related differences in CSB exist for individuals with CSA histories, with more men experiencing CSB and more women experiencing sexual avoidance (Aaron, 2012). More research is needed to further examine these relationships and consider potential confounds. For instance, CSA may lead to different behaviors in men and women in part based on traditional gender norms and socially acceptable gendered behaviors. Additionally, some research has found that women are more likely than men to report penetrative abuse and abuse by a family member (Najman et al., 2005; Rind & Tromovitch, 1997). As described by Noll et al. (2003), abuse perpetuated by one’s biological father is often conducted in the absence of physical force or violence, which may prevent the child from understanding the very real power differential that exists between the child and adult. This misperception may lead the child to engage in more self-blame than someone whom can more clearly decipher blame, which may contribute to confusion about issues concerning sexual arousal, leading to sexual ambivalence. Additionally, some research has hypothesized that any gender differences may be an artifact of more studies having been conducted on CSB among men (Blain et al., 2012;. Forouzan & Van Gijseghem, 2005; Parsons et al., 2012).

Lastly, the study design most often used for research studies was cross-sectional. More developmental longitudinal outcome studies are needed to examine how CSA may impact children, adolescents, and adults’ sexual functioning over time and influence the manifestation of particular behaviors in adulthood (e.g., problematic pornography use, engagement in frequent anonymous sex). For instance, individuals abused in adolescence may be more likely to respond by withdrawing while preschoolers and younger children may display more externalizing sexualized behavior (Kendall-Tackett, Williams, & Finkelhor, 1993). Consistently, men who experienced sexual abuse as adolescents or adults appeared to experience more erectile dysfunction than other men (Tucker, Harris, Simpson, & McKinlay, 2004). Large, contemporary, longitudinal, and nationally representative studies of U.S. adults can help elucidate many of the current questions that surround the links between CSA and CSB.

Limitations

The studies that were reviewed included samples that were racially and ethnically diverse. However, specific considerations relating to race and ethnicity (including discrimination and stress that may be experienced disproportionately among specific racial/ethnic groups) warrant additional investigation in studies of CSA and CSB. Furthermore, a number of measurements and scoring thresholds were used to assess CSB, complicating comparisons across studies. Several studies created scales to assess CSB, which may limit generalizability. As only three studies specifically examined samples reporting symptoms of CSB and/or other addictions, it is unclear how many people met full diagnostic criteria for CSBD. Similarly, assessment of CSA also varied, consistent with findings in another recent review (Scoglio, Kraus, Saczynski, Jooma, & Molnar, 2019), complicating cross-study comparisons. Relatedly, not all studies considered other types of co-occurring maltreatment. Studies that accounted for other abuse often showed these variables to explain major variance on CSB or have a cumulative impact in addition to CSA. Additionally, it is important to consider possible differences in findings across distinct populations. For instance, given that three studies focused on sex-offender populations, each with differing characteristics (adolescents in inpatient treatment, adults either incarcerated or committed to treatment, and incarcerated adults), these findings may differ from studies of non-sex-offending participants. For example, differentiating coercive sexual behaviors (that may involve exhibitionism, voyeurism, frotteurism, pedophilia, and sexual assault) from noncoercive ones may be important for diagnostic and treatment purposes and have legal implications. Lastly, as the most prevalent design was a cross-sectional, retrospective assessment of the impact of CSA on adult sexuality, causal conclusions on how sexual abuse may differentially impact people over time are limited.

Conclusions and Future Directions

CSA is a widespread public health problem and has been implicated as one of many potential precursors to CSB. This review synthesized and described research on the relationship between these two variables. Most studies supported a significant association; patterns and limitations across findings should be considered when conducting future research and informing prevention and treatment measures. In Table 2, we summarize knowledge gaps and recommend future directions in research and practice. More formalized assessments of sexual behavior and related distress and impairment could help determine whether individuals meet diagnostic criteria for CSBD to better facilitate comparisons across studies (Kraus et al., 2018). Additionally, thorough assessment of CSA characteristics can allow for both dichotomous and continuous measurements of CSA to assist in more nuanced analyses. Given the prevalence of the use of digital devices and engagement in digital media, assessment of sexual abuse should also consider image-based sexual abuse, non-consensual image sharing, and sexting behaviors (DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 2016; Johnson, M., Mishna, F., Okumu, M., Daciuk, 2018) Other mediators and moderators of the relationship between CSA and CSB should also be considered, such as co-occurring types of maltreatment, personality and psychiatric characteristics, and gender roles. Furthermore, large, contemporary, and nationally representative studies of U.S. adults are needed that include diverse groups, such as women, sexual minorities, racial/ethnic minorities, disadvantaged sociodemographic groups, and individuals with disabilities. Research that considers gender beyond binary designations should be conducted to understand relationships between gender, CSA and CSB. Longitudinal studies using a cohort design could help assess the trajectory of sexually related responses (i.e., sexual avoidance, compulsivity, and ambivalence) across the life-span. Prevention efforts should be aimed toward individuals who have experienced CSA and/or other types of abuse, particularly if they report engaging in risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. Information on warning signs of CSB should be distributed at sexual abuse treatment centers and online support groups. In treatment settings, thorough trauma-informed assessments are indicated to help identify CSA and other related exposures. Individuals with CSB who have experienced sexual abuse may benefit from trauma-focused treatments that include education about the impacts of abuse and focus on developing healthy sexual scripts. CSB can have multiple detrimental impacts on daily life. Understanding potential risk factors, such as sexual abuse, may permit more targeted and effective methods of prevention and treatment.

Table 2.

Knowledge gaps relating to CSB and CSA and approaches for addressing the gaps.

| Current Gaps | Future Directions |

|---|---|

| Assessment of CSB | Assess CSBD by ICD-11 inclusionary criteria (including distress or impairment) and how these symptoms relate to sexual behaviors. Develop standardized screening assessment to reflect this definition and update language according to new developments in conceptualization (e.g., impulse-control vs. addictive disorder) |

| Assessment of CSA | Use thorough measurement tools for CSA, including assessments of age of onset of abuse, and characteristics of the abuse/perpetrator. Assess CSA both dichotomously and continuously for more nuanced analyses of CSA and CSB. |

| Mediators and Moderators | Examine mediators and moderators of the relationship between CSA and CSB, including CSA characteristics, co-occurring types of maltreatment, personality and psychiatric characteristics, race/ethnicity and gender roles. Consider these characteristics in comparisons of links across sample types, including clinical, community, and college settings. |

| Prevalence Data | Conduct large, contemporary, and nationally representative studies of U.S. adults. Examine links between CSA and CSB among diverse groups such as women, sexual minorities, different racial/ethnic groups, disadvantaged sociodemographic populations, and individuals with disabilities. |

| Longitudinal designs | Conduct naturalistic longitudinal studies using a cohort design to assess the trajectory of sexually related responses (i.e., sexual avoidance, compulsivity, and ambivalence) across the life-span. |

| Prevention | Prevention efforts should be aimed toward individuals who have experienced CSA and/or other types of maltreatment, particularly if they report engaging in risky sexual behavior. Information on warning signs of CSB should be distributed in health care settings, including sexual abuse treatment centers, and online support groups. Public campaigns aimed at reducing stigma and shame are recommended. |

| Treatment | Clinical interviews examining CSB should assess for CSA and other types of abuse. Trauma-informed psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may help individuals understand the impacts of abuse on problematic sexual scripts and develop new patterns of behavior. Expansion of treatments to address CSB and CSA-related sequelae are warranted as CSA and CSB often co-occur with psychiatric disorders. |

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32DA037801. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance With Ethical Guidelines

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report that they have no financial conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Aalsma MC, Zimet GD, Fortenberry JD, Blythe M, & Orr DP (2002). Reports of childhood sexual abuse by adolescents and young adults: Stability over time. Journal of Sex Research. 10.1080/00224490209552149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaron M (2012). The pathways of problematic sexual behavior: A literature review of factors affecting adult sexual behavior in survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720162.2012.690678This literature review examines why some individuals may respond to CSA by withdrawal, while others respond with impulsiveness. Specifically, it describes gender of the victim and age at onset of victimization as two factors that can account for differences.

- Abajobir AA, Kisely S, Maravilla JC, Williams G, & Najman JM (2017). Gender differences in the association between childhood sexual abuse and risky sexual behaviours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.023This meta-analytic review found that childhood sexual abuse is a significant risk factor for a syndemic of risky sexual behaviors and the magnitude is similar both in females and males.

- Ainsworth MD, Blehar M, Waters E, & Wall S (1978). A psychological study of the strange situation. Patterns of Attachment. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander PC (2005). Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 10.1037/0022-006x.60.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgley R, Allard H, McCormick N, et al. (1984). Occurence in the Population In Sexual Offenses Against Children (Volume 1). Ottawa: Canadian Government Publishing Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D, & Fink L (1998). Manual for the childhood trauma questionnaire. In Manual for the childhood trauma questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, … Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain LM, Muench F, Morgenstern J, & Parsons JT (2012). Exploring the role of child sexual abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in gay and bisexual men reporting compulsive sexual behavior. Child Abuse and Neglect. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1969). Attachment and loss, vol. 1: In Attachment. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Bolus R, & Mayer EA (2007). Psychometric properties of the early trauma inventory-self report. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243824.84651.6c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes P (1989). Contrary to love: Helping the sexual addict. Center City, MN: Hazelden. [Google Scholar]

- Carnes PJ., & Delmonico DL. (1996). Childhood abuse and multiple addictions: Research findings in a sample of self-identified sexual addicts. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720169608400116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes Patrick. (1991). Don’t call it love: Recovery from sexual addiction. New York: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Carnes Patrick, & O’Hara S. (1994). Women’s Sexual Addiction Screening Test (W-SAST). Wickenburg, AZ: Unpublished Measure. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalheira A, Price C, & Neves CF (2017). Body Awareness and Bodily Dissociation Among Those With and Without Sexual Difficulties: Differentiation Using the Scale of Body Connection. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1299823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro Á, Ibáñez J, Maté B, Esteban J, Barrada JR (2019). Childhood Sexual Abuse, Sexual Behavior, and Revictimization in Adolescence and Youth: A Mini Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(2018). 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzittofis A, Savard J, Arver S, Öberg KG, Hallberg J, Nordström P, & Jokinen J (2017). Interpersonal violence, early life adversity, and suicidal behavior in hypersexual men. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 10.1556/2006.6.2017.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemezov EM, Petrova NN, & Kraus SW (2019). Compulsive Sexual Behavior in HIV-Infected Men in a Community Based Sample, Russia. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(1–2). [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo J, & Keefe-Cooperman K (2015). Understanding the Impact of Childhood Sexual Abuse on Women’s Sexuality. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 10.17744/mehc.34.1.e045658226542730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E., Miner M., Ohlerking F., & Raymond N. (2001). Compulsive sexual behavior inventory: A preliminary study of reliability and validity. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 10.1080/009262301317081070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA (2004). Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy. 10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA, & Knight RA (2019). The Relation of Childhood Abuse Experiences to Problematic Sexual Behaviors in Male Youths Who Have Sexually Offended. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-018-1279-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy W, & Schwartz M (2016). Thinking Sociologically About Image-Based Sexual Abuse: The Contribution of Male Peer Support Theory. Sexualization, Media, & Society. 10.1177/2374623816684692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson JA, Gleason N, Coleman E, & Miner MH (2018). Prevalence of Distress Associated With Difficulty Controlling Sexual Urges, Feelings, and Behaviors in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge B, Reece M, Cole SL, & Sandfort TGM (2004). Sexual compulsivity among heterosexual college students. Journal of Sex Research. 10.1080/00224490409552241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erez G, Pilver CE, & Potenza MN (2014). Gender-related differences in the associations between sexual impulsivity and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estévez A., Ozerinjauregi N., Herrero-Fernández D., & Jauregui P. (2019). The Mediator Role of Early Maladaptive Schemas Between Childhood Sexual Abuse and Impulsive Symptoms in Female Survivors of CSA. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 10.1177/0886260516645815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree MC (2002). No stones: Women redeemed from sexual shame. Fairfax, VA: Xulon. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, & Browne A (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: a conceptualization. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor David, Shattuck A, Turner HA, & Hamby SL (2014). The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouzan E, & Van Gijseghem H (2005). Psychosocial adjustment and psychopathology of men sexually abused during childhood. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 10.1177/0306624X04273650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromuth ME (1986). The relationship of childhood sexual abuse with later psychological and sexual adjustment in a sample of college women. Child Abuse and Neglect. 10.1016/0145-2134(86)90026-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia FD, & Thibaut F (2010). Sexual addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 254–260. 10.3109/00952990.2010.503823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdner A., & Allgulander C. (2009). Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire - Short Form (CTQ-SF). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1080/08039480802514366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SN, & Heffner CL (1998). Sexual addiction: Many conceptions, minimal data. Clinical Psychology Review. 10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE (2008). Impulse control disorders: A clinician’s guide to understanding and treating behavioral addictions. New York, New York: WW Norton and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Greene T, Neria Y, & Gross R (2016). Prevalence, Detection and Correlates of PTSD in the Primary Care Setting: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 10.1007/s10880-016-9449-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffee K, O’Keefe SL, Stroebel SS, Beard KW, Swindell S, & Young DH (2012). On the Brink of Paradigm Change? Evidence for Unexpected Predictive Relationships Among Sexual Addiction, Masturbation, Sexual Experimentation, and Revictimization, Child Sexual Abuse, and Adult Sexual Risk. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720162.2012.705140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J, & Hirschman L (1981). Families at risk for father-daughter incest. American Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1176/ajp.138.7.967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Gallardo-Pujol D, Pereda N, Arntz A, Bernstein DP, Gaviria AM, … Gutiérrez-Zotes JA (2013). Initial Validation of the Spanish Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form: Factor Structure, Reliability and Association With Parenting. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 10.1177/0886260512468240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma Y., Wang N., Saewyc E., & Kishor N. (2012). The relationship between sexual abuse and risky sexual behavior among adolescent boys: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.032This meta-analysis found that sexually abused boys were significantly more likely than non-abused boys to report unprotected sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, and pregnancy involvement.

- Johnson M, Mishna F, Okumu M, Daciuk J (2018). Non-Consensual Sharing of Sexts: Behaviours and Attitudes of Canadian Youth. https://doi.org/https://mediasmarts.ca/research.policy [Google Scholar]

- Kafka MP (2010). Hypersexual disorder: a proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, Vol. 39, pp. 377–400. 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, & Cain D (2004). The relationship between indicators of sexual compulsivity and high risk sexual practices among men and women receiving services from a sexually transmitted infection clinic. Journal of Sex Research. 10.1080/00224490409552231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Johnson JR, Adair V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, & Kelly JA (1994). Sexual Sensation Seeking: Scale Development and Predicting AIDS-Risk Behavior Among Homosexually Active Men. Journal of Personality Assessment. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6203_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, & Rompa D (1995). Sexual Sensation Seeking and Sexual Compulsivity Scales: Reliability, Validity, and Predicting HIV Risk Behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katehakis A (2009). Affective neuroscience and the treatment of sexual ddiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720160802708966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, & Finkelhor D (1993). Impact of sexual abuse on children: a review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychological Bulletin. 10.1080/01612840701869791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA., King DW., Vogt DS., Knight J., & Samper RE. (2006). Deployment risk and resilience inventory: A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Military Psychology. 10.1207/s15327876mp1802_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston DA, Graham FJ, & Knight RA (2017). Relations Between Self-Reported Adverse Events in Childhood and Hypersexuality in Adult Male Sexual Offenders. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-016-0873-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewska E, Grubbs JB, Potenza MN, Gola M, Draps M, & Kraus SW (2018). Neurocognitive Mechanisms in Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder. Current Sexual Health Reports. 10.1007/s11930-018-0176-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krahé B, & Berger A (2017). Gendered pathways from child sexual abuse to sexual aggression victimization and perpetration in adolescence and young adulthood. Child Abuse and Neglect. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus SW, Krueger RB, Briken P, First MB, Stein DJ, Kaplan MS, … Reed GM (2018). Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry. 10.1002/wps.20499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus SW, Voon V, & Potenza MN (2016). Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addiction, 111(12), 2097–2106. 10.1111/add.13297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma JM, & Black DW (2008). Epidemiology, Prevalence, and Natural History of Compulsive Sexual Behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.005This review article describes the core features, prevalence, common psychiatric and medical comorbidities, gender distribution, natural history, family history and risk factors associated with CSB.

- Lacelle C, Hébert M, Lavoie F, Vitaro F, & Tremblay RE (2012). Sexual health in women reporting a history of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Långström N, & Hanson RK (2006). High rates of sexual behavior in the general population: Correlates and predictors. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-006-8993-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb RT, Paulozzi LJ, Melanson C, Simon TR, & Arias I (2008). Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 10.1177/1077559599004001005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lisak D, & Beszterczey S (2007). The cycle of violence: The life histories of 43 death row inmates. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 10.1037/1524-9220.8.2.118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb TB, Williams JK, Vargas J, Wyatt GE, & O’Brien AA (2002). Child sexual abuse: Associations with the sexual functioning of adolescents and adults. Annual Review of Sex Research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LE, & Marshall WL (2006). Sexual addiction in incarcerated sexual offenders. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720160601011281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson S, Clayton S, Wood H, Hiskey S, & Andrews L (2013). The Role of Childhood Experiences in the Development of Sexual Compulsivity. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720162.2013.803213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Heiman JR, & Trapnell PD (1999). The relation between early abuse and adult sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 10.1080/00224499909552011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D., Cohn A., Robinson B., Muse F., & Hughes R. (2017). Persistent Complications of Child Sexual Abuse: Sexually Compulsive Behaviors, Attachment, and Emotions. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 10.1080/10538712.2016.1269144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Nguyen A, Cohen JA (2014). Child Sexual Abuse. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 321–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Dunne MP, Purdie DM, Boyle FM, & Coxeter PD (2005). Sexual abuse in childhood and sexual dysfunction in adulthood: An Australian population-based study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-005-6277-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, & Putnam FW (2003). A prospective investigation of the impact of childhood sexual abuse on the development of sexuality. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odlaug BL, Lust K, Schreiber LRN, Christenson G, Derbyshire K, Harvanko A, … Grant JE (2013). Compulsive sexual behavior in young adults. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 25(3), 193–200. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23926574 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz DM, Tsytsarev SV, & Froh J (2009). Women’s sexual addiction and family dynamics, depression and substance abuse. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 16(4), 324–340. 10.1080/10720160903375749 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Grov C, & Golub SA (2012). Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: Further evidence of a syndemic. American Journal of Public Health. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT., Millar BM., Moody RL., Starks TJ., Rendina HJ., & Grov C. (2017). Syndemic conditions and HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in a U.S. National sample. Health Psychology. 10.1037/hea0000509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Moody RL, Ventuneac A, & Grov C (2015). Syndemic Production and Sexual Compulsivity/Hypersexuality in Highly Sexually Active Gay and Bisexual Men: Further Evidence for a Three Group Conceptualization. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-015-0574-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrero Pérez EJ, Rodríguez Monje MT, Gallardo Alonso F, Fernández Girón M, Pérez López M, & Chicharro Romero J (2007). Validación de un instrumento para la detección de trastornos de control de impulsos y adicciones: El MULTICAGE CAD-4. Trastornos Adictivos. 10.1016/S1575-0973(07)75656-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perera B, Reece M, Monahan P, Billingham R, & Finn P (2009). Childhood characteristics and personal dispositions to sexually compulsive behavior among young adults. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720160902905421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plant M, Plant M, & Miller P (2005). Childhood and Adult Sexual Abuse: Relationships with ‘Addictive’ or ‘Problem’ Behaviours and Health. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 10.1300/J069v24n01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C (2007). Dissociation reduction in body therapy during sexual abuse recovery. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam FW (2003). Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellini AH., & Meston CM. (2011). Sexual self-chemas, sexual dysfunction, and the sexual responses of women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-010-9694-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rind B, & Tromovitch P (1997). A meta-analytic review of findings from national samples on psychological correlates of child sexual abuse. Journal of Sex Research. 10.1080/00224499709551891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney BM, Tulloch TG, & Blashill AJ (2018). Psychosocial Syndemic Correlates of Sexual Compulsivity Among Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Meta-Analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-017-1032-3This meta-analysis of MSM examining CSA and other factors as syndemic predictors of sexual compulsivity found a statistically significant small effect size between CSA and CSB.

- Schloredt KA, & Heiman JR (2003). Perceptions of sexuality as related to sexual functioning and sexual risk in women with different types of childhood abuse histories. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 10.1023/A:1023752225535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JP, & Irons RR (2001). Assessment and treatment of addictive sexual disorders: Relevance for chemical dependency relapse. Substance Use and Misuse. 10.1081/JA-100108428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MF, & Southern S (2000). Compulsive cybersex: The new tea room. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720160008400211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scoglio AAJ, Kraus SW, Saczynski J, Jooma S, & Molnar BE (2019). Systematic Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Revictimization After Child Sexual Abuse. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 10.1177/1524838018823274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skegg K., Nada-Raja S., Dickson N., & Paul C. (2010). Perceived “out of control” sexual behavior in a cohort of young adults from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health And Development study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-009-9504-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Potenza MN, Mazure CM, Mckee SA, Park CL, & Hoff RA (2014). Compulsive sexual behavior among male military veterans: Prevalence and associated clinical factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.4.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, George WH, Staples JM, Nguyen H, Davis KC, Kaysen D, … Kajumulo KF (2016). In-The-Moment Dissociation, Emotional Numbing, and Sexual Risk: The Influence of Sexual Trauma History, Trauma Symptoms, and Alcohol Intoxication. Psychology of Violence. 10.1037/a0039978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Klucken T, Potenza MN, Brand M, & Strahler J (2018). A Current Understanding of the Behavioral Neuroscience of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder and Problematic Pornography Use. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 10.1007/s40473-018-0162-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan H (1954). THE INTERPERSONAL THEORY OF PSYCHIATRY. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 10.1097/00005053-195407000-00064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend C, & Rheingold AA (2013). Estimating a Child Sexual Abuse Prevalence Rate for Practitioners: A Review of Child Sex Abuse Prevalence Studies. Darkness to Light. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker RD, Harris SS, Simpson WB, & McKinlay JB (2004). The relationship between adult or adolescent sexual abuse and sexual dysfunction: preliminary results from the Boston Area Community Health Survey (BACH). Annals of Epidemiology, 14(8), 621 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.07.079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt-Morel M-P, Godbout N, Labadie C, Runtz M, Lussier Y, & Sabourin S (2015). Avoidant and compulsive sexual behaviors in male and female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Godbout N, Sabourin S, Briere J, Lussier Y, & Runtz M (2016). Adult Sexual Outcomes of Child Sexual Abuse Vary According to Relationship Status. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 10.1111/jmft.12154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, Koss MP, Von Korff M, Bernstein D, & Russo J (1999). Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. American Journal of Medicine. 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00235-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Blaustein M, Knight WG, Spinazzola J, & van der Kolk BA (2007). Resiliency Factors in the Relation Between Childhood Sexual Abuse and Adulthood Sexual Assault in College-Age Women. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 10.1300/J070v16n01_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womack SD, Hook JN, Ramos M, Davis DE, & Penberthy JK (2013). Measuring Hypersexual Behavior. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 10.1080/10720162.2013.768126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1999). Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention (WHO/HSC/PVI/ 99.1). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mip2001/files/2017/childabuse.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2003). Management of Substance Abuse: The GENACIS Project. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/en/GENACISFactSheet.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization. (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en