Abstract

Background

Severe coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) presents with progressive dyspnea, which results from acute lung inflammatory edema leading to hypoxia. As with other infectious diseases that affect the respiratory tract, asthma has been cited as a potential risk factor for severe COVID-19. However, conflicting results have been published over the last few months and the putative association between these two diseases is still unproven.

Methods

Here, we systematically reviewed all reports on COVID-19 published since its emergence in December 2019 to June 30, 2020, looking into the description of asthma as a premorbid condition, which could indicate its potential involvement in disease progression.

Results

We found 372 articles describing the underlying diseases of 161,271 patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Asthma was reported as a premorbid condition in only 2623 patients accounting for 1.6% of all patients.

Conclusions

As the global prevalence of asthma is 4.4%, we conclude that either asthma is not a premorbid condition that contributes to the development of COVID-19 or clinicians and researchers are not accurately describing the premorbidities in COVID-19 patients.

Keywords: Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, Allergy, Respiratory insufficiency, Lung

Background

COVID-19 was first reported in December, 2019 in Wuhan, China, and rapidly spread across the globe [1]. It has affected more than 54 million people and has led to the death of over 1.3 million as of November 16, 2020 (www.who.org). Severely affected patients present fever, dry cough, dyspnea, and fatigue, which are commonly associated with the development of pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [2]. Advanced age, ischemic and congestive heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are the most important independent predictors of death [2, 3]. As with other infectious diseases affecting the lungs, asthma has been cited as a potential risk factor for severe COVID-19 [4–8]. This association could be putatively explained on the basis of an abnormal immune response occurring in the context of the allergic condition and an abnormal respiratory function [9, 10]. However, no previous study has addressed this question looking into all studies that described the clinical features of COVID-19.

Here, we systematically reviewed all studies published on COVID-19 since its emergence in December 2019 to June 30, 2020, looking into the description of asthma as a premorbid condition and its putative association with severe progression of the disease. We show that out of 161,271 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and having their premorbid conditions described, only 1.6% were reported as previously diagnosed with asthma.

Methods

This is a systematic review of the diagnosis of asthma as a premorbid condition in patients with COVID-19. The report was organized according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews [11]. Two authors, NFM and CPJ, independently identified cross-sectional and longitudinal studies published before June 30, 2020, that reported on the prevalence of asthma as a premorbid condition of severe COVID-19 by systematically searching PubMed-NCBI, Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science databases. As previously reported, PubMed-NCBI alone covers more than 90% of MEDLINE providing a widely accessible biomedical resource [12]. For database searches, language of the article was restricted to English. Search terms included the following: COVID-19 (COVID, COVID 19) or nCov or novel coronavirus or Sars-Cov-2 in the title and clinical characteristics or asthma anywhere in the text. Three authors, EM, EPA, and LAV, resolved eventual discrepancies by discussion and adjudication.

We found 1069 articles that met the initial inclusion search criteria. All articles were assessed by authors and 598 were excluded (Additional file 1: Table 1) due to one or more of the following criteria: editorials; metanalyses; systematic reviews; commentaries; letters to the Editor; no description of patient’s clinical characteristics or premorbid conditions; duplicated articles and main text in a language other than English. We found 99 studies duplicated, which were also excluded accordingly, allowing us to analyze only in one of the both versions. The remaining 372 articles were included in the study. Additional file 1: Table 2 depicts the details of all articles analyzed.

Two authors, NFM and CPJ, independently extracted the following data from each article using a standardized form: study design; number of patients with COVID-19; mention of any respiratory disease; number of patients with any respiratory disease; mention of asthma; number of patients with the previous diagnosis of asthma. The entire body of the articles was presented descriptively.

Results

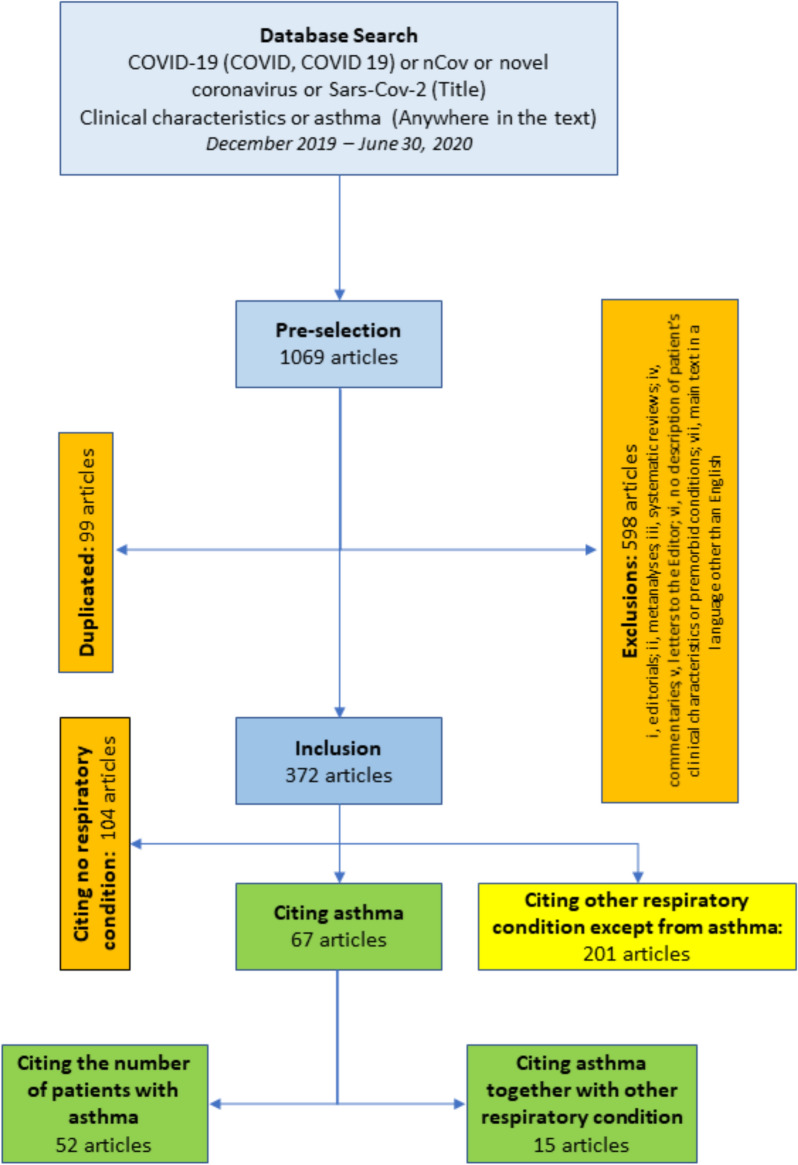

Figure 1 is a schematic representation of search, inclusion and exclusion of articles. Our search criteria resulted in the identification of 1069 articles that were pre-selected for detailed analysis resulting in the exclusion of 598 articles (Additional file 1: Table 1) due to one or more of the following reasons: editorials; metanalyses; systematic reviews; commentaries; letters to the Editor; no description of patient’s clinical characteristics or premorbid conditions; and main text in a language other than English. The remaining 372 articles (Additional file 1: Table 2) described the clinical aspects of 161,271 COVID-19 patients. Two hundred and one studies mentioned the existence of other respiratory premorbidities except for asthma. Althought asthma was mentioned as a underlying disease in 67 studies, only 52 articles have described the exact number of the COVID-19 patients with asthma (Table 1). The other 15 studies presented asthma together with other respiratory diseases, making it impossible to identify the number of COVID-19 asthmatic patients. There was a total of 40,948 COVID-19 patients included in the studies mentioning asthma, of which 8439 were previously diagnosed with asthma. In most of the studies describing other respiratory illnesses, COPD was the leading diagnosis. The United States was the country with the largest number of studies describing asthma, followed by China, France, Spain and the United Kingdom (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of search, exclusions and inclusions of articles

Table 1.

Details of the articles that mention asthma

| Citation | Title | DOI | Mention to respiratory disease except from asthma | Number (%) respiratory disease except from asthma | Mention to asthma | Number (%) asthma patients | Number of COVID-19 patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkundi A, et al.. | Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalized patients with diabetes in the United Kingdom: A retrospective single centre study | 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108263 | Yes | COPD: 7 (7.3%) | Yes | 6 (2.6%) | 232 |

| Alsofayan YM, et al. | Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: A national retrospective study | 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.026 | Yes | Chronic lung disease: 57 (5.2%) | Yes | 54 (4.9%) | 1519 |

| Aretz M, et al. | Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 in Washington State | 10.1001/jama.2020.4326 | Yes | COPD: 7 (33.3%) | Yes | 2 (9.1%) | 21 |

| Asghar MS, et al. | Clinical Profiles, Characteristics, and Outcomes of the First 100 Admitted COVID-19 Patients in Pakistan: A Single-Center Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Karachi | 10.7759/cureus.8712 | Yes | COPD: 3 (3%) | Yes | 2 (2%) | 100 |

| Benger M, et al. | Intracerebral haemorrhage and COVID-19: Clinical characteristics from a case series | 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.005 | No | – | Yes | 1 (20%) | 5 |

| Bhatraju PK, et al. | Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region — Case Series | 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500 | Yes | COPD: 1 (4%) | Yes | 3 (12.5%) | 24 |

| Chao JY, et al. | Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Hospitalized and Critically Ill Children and Adolescents with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) at a Tertiary Care Medical Center in New York City | 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006 | No | – | Yes | 11 (24.4%) | 46 |

| Cheng FY, et al. | Using Machine Learning to Predict ICU Transfer in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients | 10.3390/jcm9061668 | Yes | COPD: 219 (8.42%) | Yes | 219 (8.42%) | 2599 |

| Cheung ZB and Forsh DA | Early outcomes after hip fracture surgery in COVID-19 patients in New York City | 10.1016/j.jor.2020.06.003 | Yes | COPD: 1 (10%) | Yes | 2 (20%) | 10 |

| Chhiba KD, et al. | Prevalence and characterization of asthma in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 | 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.010 | Yes | COPD: 111 (7.27%) | Yes | 220 (14.2%) | 1542 |

| D'Silva KM, et al. | Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and rheumatic disease: a comparative cohort study from a US 'hot spot' | 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217888 | Yes | COPD: 9 (5.7%) | Yes | 31 (19.8%) | 156 |

| Du H, et al. | Clinical characteristics of 182 pediatric COVID-19 patients with different severities and allergic status | 10.1111/all.14452 | No | – | Yes | 1 (2.3%) | 43 |

| Duanmu Y, et al. | Characteristics of Emergency Department Patients With COVID-19 at a Single Site in Northern California: Clinical Observations and Public Health Implications | 10.1111/acem.14003 | Yes | COPD: 1 (10%) | Yes | 10 (10%) | 100 |

| Fan J, et al. | The epidemiology of reverse transmission of COVID-19 in Gansu Province, China | 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101741 | Yes | COPD: N/A | Yes | N/A | 37 |

| Fernandéz R, et al. | COVID-19 in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Case Series from Spain | 10.1111/ajt.15929 | No | – | Yes | 1 (5.55%) | 18 |

| Gayam V, et al. | Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes of patients coinfected with COVID-19 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the USA | 10.1002/jmv.26026 | No | – | Yes | 2 (33.3%) | 6 |

| Gold JAW, et al. | Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Adult Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19—Georgia, March 2020 | 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1 | Yes | COPD: 16 (5.2%) | Yes | 32 (10.5%) | 305 |

| Goyal P, et al. | Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City | 10.1056/NEJMc2010419 | Yes | COPD: 20 (5.1%) | Yes | 49 (12.5%) | 393 |

| Huang D, et al. | A novel risk score to predict diagnosis with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected patients: A retrospective, multicenter, and observational study | 10.1002/jmv.26143 | Yes | COPD: 9 (2.7%) | Yes | 5 (1.5%) | 336 |

| Jehi L, et al. | Individualizing Risk Prediction for Positive Coronavirus Disease 2019 Testing: Results From 11,672 Patients | 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.580 | Yes | COPD/emphysema: 14 (1.26%) | Yes | 163 (14.7%) | 1108 |

| Kaushik S, et al. | Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection (MIS-C): A Multi-institutional Study from New York City | 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.045 | No | – | Yes | 5 (15%) | 33 |

| Knight M, et al. | Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population-based cohort study | 10.1136/bmj.m2107 | No | – | Yes | 31 (7%) | 427 |

| Korkmaz MF, et al. | The Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 81 Children with COVID-19 in a Pandemic Hospital in Turkey: an Observational Cohort Study | 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e236 | No | – | Yes | 1 (1.23%) | 81 |

| Lechien JR, et al.. 2020 | Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of 1,420 European Patients With Mild-To-Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019 | 10.1111/joim.13089 | Yes | Respiratory insufficiency: 10 (0.7%) | Yes | 93 (6.5%) | 1420 |

| Li X, et al.. 2020 | Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan | 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006 | Yes | COPD: 17 (3.1%) | Yes | 5 (0.9%) | 548 |

| Liabeuf S, et al. | Association between renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and COVID-19 complications | 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa062 | Yes | COPD: 26 (10%) | Yes | 14 (5%) | 268 |

| Liu BM, et al. | Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 patients in convalescence period | 10.1017/S0950268820001181 | Yes | Pulmonary tuberculosis: 4 (5.9%) | Yes | 1 (1.5%) | 68 |

| Liu D, et al. | The pulmonary sequalae in discharged patients with COVID-19: a short-term observational study | 10.1186/s12931-020.01385-1 | No | – | Yes | 4 (2.8%) | 149 |

| Lokken EM, et al. | Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in Washington State | 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.031 | No | – | Yes | 4 (8.7%) | 46 |

| Magagnoli et al. | Outcomes of Hydroxychloroquine Usage in United States Veterans Hospitalized with COVID-19 | 10.1016/j.medj.2020.06.001 | Yes | COPD: 175 (21.68%) | Yes | 40 (4.95%) | 807 |

| Mestre-Goméz B, et al. | Incidence of pulmonary embolism in non‑critically ill COVID‑19 patients. Predicting factors for a challenging diagnosis | 10.1007/s11239-020-02190-9 | Yes | Chronic obstrutive lung disease: 13 (14.28%) | Yes | 7 (7.69%) | 91 |

| Mikami T, et al. | Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in New York City | 10.1007/s11606-020-05983-z | Yes | COPD: 176 (2.7%) | Yes | 271 (4.2%) | 6493 |

| Mitra AR, et al. | Baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in Vancouver, Canada: a case series | 10.1503/cmaj.200794 | Yes | COPD: 8 (6.8%) | Yes | 14 (12%) | 117 |

| Oualha M, et al. | Severe and fatal forms of COVID-19 in children | 10.1016/j.arcped.2020.05.010 | Yes | COPD: 1 (3.7%) e Chronic lung disease: 2 (7.4%) | Yes | 1 (3.7%) | 27 |

| Pare JR, et al. | Point-of-care Lung Ultrasound Is More Sensitive than Chest Radiograph for Evaluation of COVID-19 | 10.5811/westjem.2020.5.47743 | Yes | COPD: 1 (3.7%) | Yes | 4 (14.8%) | 27 |

| Peyrony O, et al. | Accuracy of Emergency Department Clinical Findings for Diagnosis of Coronavirus Disease 2019 | 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.05.022 | Yes | COPD: 24 (6.2%) | Yes | 22 (5.7%) | 391 |

| Phipps MM, et al. | Acute Liver Injury in COVID-19: Prevalence and Association with Clinical Outcomes in a Large US Cohort | 10.1002/hep.31404 | Yes | COPD: 185 (8.1%) | Yes | 308 (14) | 2273 |

| Pongpirul WA, et al. | Clinical Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Coronavirus Disease, Thailand | 10.3201/eid2607.200598 | Yes | COPD: 0 | Yes | 0 | 11 |

| Price-Haywood EG, et al. | Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19 | 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686 | Yes | COPD: 79 (2.25%) | Yes | 147 (4%) | 3481 |

| Richardson S, et al. | Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area | 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 | Yes | COPD: 287 (5.4%) | Yes | 479 (9%) | 5700 |

| San-Juan R, et al. | Incidence and clinical profiles of COVID-19 pneumonia in pregnant women: A single-centre cohort study from Spain | 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100407 | No | – | Yes | 4 (12.5%) | 32 |

| Satici C, et al. | Performance of pneumonia severity index and CURB-65 in predicting 30-day mortality in patients with COVID-19 | 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.038 | Yes | COPD: 28 (4.1%) | Yes | 43 (6.3%) | 681 |

| Sentilhes L, et al. | Coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy was associated with maternal morbidity and preterm birth | 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.022 | No | – | Yes | 5 (9.3%) | 54 |

| Shahriarirad R, et al. | Epidemiological and clinical features of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in the South of Iran | 10.1186/s12879-020-05128-x | Yes | COPD: 9 (8%) | Yes | 7 (6.2%) | 113 |

| Smith SM, et al. | Impaired glucose metabolism in patients with diabetes, prediabetes and obesity is associated with severe Covid-19 | 10.1002/jmv.26227 | Yes | COPD: 12 (6.5%) | Yes | 18 (9.8%) | 184 |

| Solís and Carreňo | COVID-19 Fatality and Comorbidity Risk Factors among Diagnosed Patients in Mexico | 10.1101/2020.04.21.20074591 | Yes | COPD: 202 (2.7%) | Yes | 270 (3.6%) | 7497 |

| Sultan I, et al. | The Role of Extracorporeal Life Support for Patients With COVID-19: Preliminary Results from a Statewide Experience | 10.1111/jocs.14583 | No | – | Yes | N/A | 10 |

| Wang X, et al. | Nosocomial Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Wuhan, China | 10.1183/13993003.00544-2020 | No | – | Yes | 2 (5.7%) | 35 |

| Zhang C, et al. | Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infections in China: A multicenter case series | 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003130 | No | – | Yes | 1 (3%) | 34 |

| Zhang JJ, et al. | Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China | 10.1111/all.14238 | Yes | COPD: 2 (1.4%) | Yes | 0 | 140 |

| Zhao M, et al. | Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 at different ages | 10.18632/aging.103298 | Yes | COPD: 23 (2.3%) | Yes | 12 (1.2%) | 1000 |

| Zhou X, et al. | Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Patients with Hypertension on Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitors | 10.1080/10641963.2020.1764018 | Yes | COPD:3 (2.7%) | Yes | 1 (0.9%) | 110 |

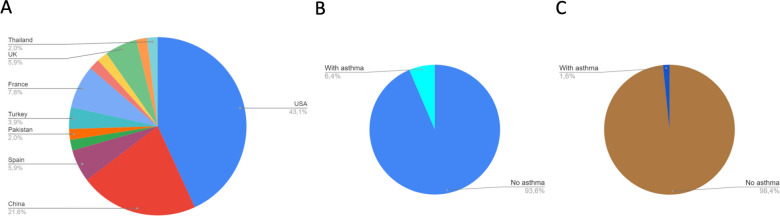

Fig. 2.

Graphic representation of the geographical origin of the studies analyzed in the systematic review (a) and the proportion of patients with previous diagnosis of asthma among COVID-19 patients included in studies citing asthma (b) and among all COVID-19 patients described up to June 30, 2020 (c)

Thus, according to current COVID-19 clinical records, 6.4% of patients included in articles describing the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients and citing asthma were previously diagnosed with asthma (Fig. 2b). If all studies providing any clinical description of COVID-19 comorbidities are taken into consideration, asthma was present in only 1.6% of patients (Fig. 2c).

Discussion

Asthma is a highly prevalent, chronic, non-communicable disease that affects up to 4.4% of the world’s population (http://www.globalasthmareport.org; https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/asthma). Its recurrent nature leads to frequent hospitalizations and high mortality, ranging from 2 to 4/100,000 [13]. Respiratory viruses can trigger asthma exacerbations, which can increase the severity of the infectious condition [14]. In the past, coronaviruses have been implicated as triggers of asthma exacerbations [15, 16]; this is also true for influenza virus [17]. However, as for the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, there is still controversy regarding the putative role of asthma as a premorbid that could worsen disease progression [7, 8, 18].

Here, we evaluated all studies on COVID-19 published since its emergence up to June 30, 2020. We showed that asthma was described as a premorbid condition in only 1.6% of all patients. These numbers are far less than expected considering the prevalence of asthma in the world (http://www.globalasthmareport.org; https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/asthma) and could suggest that having asthma as a premorbid condition either represents no risk for COVID-19 or could be a protective factor against the development of the disease. However, there are some aspects that should be considered as potentially impactful for the findings herein reported. First, the prevalence of asthma varies across the globe, ranging from 21% in Australia to less than 2% in China, Kazakhstan and Vietnam [19]. Likewise, the most common risk factors for COVID-19, obesity, diabetes and hypertension, have distinct prevalences in different countries (www.who.org). Thus, the geographical origin of the studies could have influenced the results. However, as the studies included in this systematic review were mostly originated from countries presenting a wide range of prevalences for both asthma and the main comorbidities for COVID-19, we believe this factor plays a minor role in the reported findings.

Another aspect that could explain our results is that asthma treatment with inhaled corticosteroids allied to improved therapeutic and prophylactic adhesion has increased over the years, resulting in the reduction of respiratory distress episodes and allergy associated immunological imbalance [20–23]. Moreover, allergy and asthma international associations were efficient to rapidly produce and release COVID-19 guidelines that provided advice for health professionals involved in the care of asthma patients, as well as for reaching the general public [24–27]. These actions could have beneficially impacted on the control of asthma and also influenced patients to follow social isolation procedures; thus, mitigating the risk of contracting COVID-19.

It has been suggested that the particular inflammatory environment in the bronchioalveolar system of asthma patients could lead to a reduced expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), rendering asthma patients protected from the infection [28–30]. This could be due to the fact that interleukin-13 (IL-13), a cytokine involved in eosinophil recruitment to the bronchial epithelia [31], is capable of reducing ACE2 expression in bronchial ex-vivo human samples [28]. In line with these findings, it has been reported that progressive increase in blood eosinophil counts is related to COVID-19 recovery. Thus, if proven correct, these data could suggest that only patients with allergic asthma are protected from COVID-19, as recently suggested [32, 33]. However, currently available data provides no sufficient detail regarding asthma etiological classification and further studies would be required in order to provide advance in this issue.

The main weaknesses of this systematic review rely on the facts that we included publications covering the initial 6 months of pandemics and as new data is published on a daily basis, some changes in the frequency of asthma could appear; moreover, readers should keep in mind that some reports show that in certain pocket populations, asthma could be an important comorbidity for COVID-19 [34]. The reasons for these apparent discrepancies should be a focus of further studies.

Thus, as for the data analyzed in this systematic review, asthma does not seem to be an important premorbid condition in COVID-19 patients; or, conversely, it could be a protective factor, as previously proposed [18]. The findings herein reported could be an epidemiological truth that should be further explored in mechanistic studies or could be due to the fact that researchers are not properly investigating and describing the premorbidities in COVID-19 patients. Whatever the reasons, the medical community should be aware of the implications of missing the diagnosis of a potentially severe respiratory disease such as asthma that could worsen the prognosis of COVID-19 patients.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table 1. Excluded articles. Table 2. Included articles.

Acknowledgements

We thank our grant providers.

Authors’ contributions

NFM and CPJ performed article search and first round of inclusions. EM, EPA and LAV performed second round of inclusion. LAV and NFM performed statistics analysis. LAV and NFM wrote the manuscript. All authors read manuscript and provided approval.

Funding

NFM was supported by The São Paulo Research Foundation (grant: 2016/17810-3), and CPJ was supported by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) grant: 1744875 and 88882.434715/2019-01. EM, LAV and EPA are supported by grants from São Paulo Research Foundation (grants: 2013/07607-8 and 2020/) and Brazilian National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study does not require ethical approval because the systematic review is based on published research and the original data are anonymous.

Consent for publication

Authors are the sole responsible for the publication of this study.

Competing interests

Authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13223-020-00509-y.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehra MR, Desai SS, Kuy S, Henry TD, Patel AN. Cardiovascular disease, drug therapy, and mortality in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4.Shaker MS, Oppenheimer J, Grayson M, Stukus D, Hartog N, Hsieh EWY, et al. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1477.e5–1488.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston SL. Asthma and COVID-19: is asthma a risk factor for severe outcomes? Allergy. 2020;75:1543–1545. doi: 10.1111/all.14348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegde S. Does asthma make COVID-19 worse? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:352. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caminati M, Lombardi C, Micheletto C, Roca E, Bigni B, Furci F, et al. Asthmatic patients in COVID-19 outbreak: few cases despite many cases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(3):541–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie AI, Jackson DJ, Edwards MR, Johnston SL. Airway epithelial orchestration of innate immune function in response to virus infection. A focus on asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13 Suppl 1:S55–63. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-421MG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Lung dendritic cells in respiratory viral infection and asthma: from protection to immunopathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:243–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson PO, Minter CIJ. Exploring PubMed as a reliable resource for scholarly communications services. J Med Libr Assoc. 2019;107(1):16–29. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2019.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennington E, Yaqoob ZJ, Al-Kindi SG, Zein J. Trends in asthma mortality in the United States: 1999 to 2015. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(12):1575–1577. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1844LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng XY, Xu YJ, Guan WJ, Lin LF. Regional, age and respiratory-secretion-specific prevalence of respiratory viruses associated with asthma exacerbation: a literature review. Arch Virol. 2018;163(4):845–853. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3700-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntosh K, Ellis EF, Hoffman LS, Lybass TG, Eller JJ, Fulginiti VA. The association of viral and bacterial respiratory infections with exacerbations of wheezing in young asthmatic children. J Pediatr. 1973;82(4):578–590. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(73)80582-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson KG, Kent J, Ireland DC. Respiratory viruses and exacerbations of asthma in adults. BMJ. 1993;307(6910):982–986. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6910.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sposato B, Croci L, Canneti E, Di Tomassi M, Migliorini MG, Ricci A, et al. Influenza A H1N1 and severe asthma exacerbation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14(5):487–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carli G, Cecchi L, Stebbing J, Parronchi P, Farsi A. Is asthma protective against COVID-19? Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS, Bateman ED, Cruz AA, et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:204. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley IL, Jackson B, Crabtree D, Riebl S, Que LG, Pleasants R, et al. A scoping review of international barriers to asthma medication adherence mapped to the theoretical domains framework. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeminiwa R, Hohmann L, Qian J, Garza K, Hansen R, Fox BI. Impact of eHealth on medication adherence among patients with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2019;149:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagne M, Boulet LP, Perez N, Moisan J. Adherence stages measured by patient-reported outcome instruments in adults with asthma: a scoping review. J Asthma. 2020;57(2):179–187. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1565823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison T, Pavord ID, Chalmers JD, Whelan G, Fageras M, Rutgersson A, et al. Variability in airway inflammation, symptoms, lung function and reliever use in asthma: anti-inflammatory reliever hypothesis and STIFLE study design. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6:00333-2019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00333-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaar O, Klimek L, Jutel M, Akdis CA, Bousquet J, Breiteneder H, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: practical considerations on the organization of an allergy clinic—an EAACI/ARIA position paper. Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Licskai C, Yang CL, Ducharme FM, Radhakrishnan D, Podgers D, Ramsey C, et al. Key highlights from the Canadian thoracic society position statement on the optimization of asthma management during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Chest. 2020;158(4):1335–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ish P, Malhotra N, Gupta NGINA. what's new and why? J Asthma. 2020;2020:1–5. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2020.1788076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klimek L, Jutel M, Bousquet J, Agache I, Akdis C, Hox V, et al. Management of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis during the COVID-19 pandemic—an EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura H, Francisco D, Conway M, Martinez FD, Vercelli D, Polverino F, et al. Type 2 inflammation modulates ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in airway epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):80e8–88 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez-Cedillo A, Garcia-Valdivieso MG, Hernandez-Arteaga AC, Patino-Marin N, Vertiz-Hernandez AA, Jose-Yacaman M, et al. Determination of sialic acid levels by using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy in periodontitis and gingivitis. Oral Dis. 2019;25(6):1627–1633. doi: 10.1111/odi.13141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sidarta-Oliveira D, Jara CP, Ferruzzi AJ, Skaf MS, Velander WH, Araujo EP, et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor is co-expressed with elements of the kinin-kallikrein, renin-angiotensin and coagulation systems in alveolar cells. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19522. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76488-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar RK, Herbert C, Yang M, Koskinen AM, McKenzie AN, Foster PS. Role of interleukin-13 in eosinophil accumulation and airway remodelling in a mouse model of chronic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32(7):1104–1111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang JM, Koh HY, Moon SY, Yoo IK, Ha EK, You S, et al. Allergic disorders and susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19: a nationwide cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(4):790–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keswani A, Dhana K, Rosenthal JA, Moore D, Mahdavinia M. Atopy is predictive of a decreased need for hospitalization for coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(4):479–481. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table 1. Excluded articles. Table 2. Included articles.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.