Abstract

In the 1970s intimate partner violence became recognized as a major societal problem in Europe. The study of the processes that enable victims to emerge from this violence is still topical. Even more so when it concerns male victims, who remain an under-studied population. This article examines the processes involved in bringing an end to intimate partner violence, including female and male victims. This qualitative study examines the intra- and inter-subjective changes underlying the processes of ending IPV in victims by using a narrative approach. Semi-structured interviews including the use of qualitative life calendars were conducted with 21 victims, 18 women and 3 men. The thematic analysis highlighted eight stages of a process of getting out from intimate partner violence. From the change in perception to the post-separation, victims’ trajectories contain similar stages nuanced by individual and environmental specificities for both female and male. Getting out from intimate partner violence involves a sequence of changes in the perception of self, partner, couple and violence that allows for cognitive and relational transitions.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence - victims, Getting out from violence - subjective changes - processes

The 1970s saw violence against women and intimate partner violence recognized as real social problems and become central issues in European political agenda. Since then, research on the subject has increased. The associated question of the processes underlying how his violence might be brought to an end is still relevant. Even more so for male victims who remain an under-studied population. Through a Belgian study based on narratives thematic analysis, this article examines the trajectory of 21 victims, including female and male, of intimate partner violence (IPV, i.e. “Any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm or suffering to the persons who are part of it” (Krug et al. 2002)).

Intimate Partner Violence as a Societal Problem

The principle of equal treatment between women and men has been guaranteed in Europe since 1950s. However, it was not until the 1970s that the rise of feminist movements saw the development of a new analysis axis of social relations between men and women (Pieters et al. 2010). In 1997, domestic violence became the subject of concerted public attention in Belgium when a law introduced the notion of felony in the case of intentional assault against a spouse or former spouse.1 Belgium’s position against domestic violence was strengthened with the adoption, in 2006, of the “Tolerance Zero policy” (Mélan 2017; Vanneste 2017). Since then, a considerable amount of research has been dedicated to victims leaving violent relationships. All agree that it is a long and difficult process involving multiple variables (Hendy et al. 2003; Offermans and Kacenekenbogen 2010; Catallo et al. 2013). However, it is clear that many of these studies focus almost exclusively on female victims. Studies of battered men and their trajectories remain scarce (Jaillet and Vanneste 2017).

“Getting Out From” Intimate Partner Violence

Most victims of IPV are women living with their partners and victims of many forms of violence, including verbal, psychological, economic, physical and sexual violence. Cases of IPV occur in all backgrounds, social classes and age groups but vary according to social class, ethnic origin or religion (Davis 2002; Corbeil and Marchand 2006; Offermans and Kacenekenbogen 2010; Dieu and Hirschelmann 2017). The consequences of such violence vary according to their form, frequency and intensity, but they always involve physical and psychological suffering (Band-Winterstein and Eisikovits 2014). The symptoms of the latter are similar to those of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, which is commonly identified in victims of domestic violence (Zlotnick et al. 2006). It upsets their fundamental conceptions, their perception of the world and/or themselves and their or relation to the world. This could affect the process of extricating themselves from violent relationships (Brillon et al. 1996; Woods 2000).

A Process of Change

Process studies consider change as incremental mechanisms (Mills 1985; Wuest and Merritt-gray 1999; Cluss et al. 2006). A good example is Prochaska and DiClemente’s Transtheoretical Model of Change, which considers our ways of thinking as processes of change (Burman 2003; Burke et al. 2004; Burke et al. 2009; Chang et al. 2006). These conceptual frameworks consider exit as a primarily emotional and cognitive evolution that begins within the relationship and may extend beyond physical separation (Reisenhofer and Taft 2013). In this way, leaving a violent relationship is particulary difficult. The cyclical aspect of violence impacts the victims’ ability to perceive success in their actions and reduces their motivation to react (Ali and McGarry 2018). Moreover, most abused women feel that they are responsible for the violence (Wahed and Bhuiya 2007; Heim et al. 2018). In order to survive, they vill tend to overestimate the positive aspects of the relationship and maintain hope for change (Herbert et al. 1991; Hendy et al. 2003). This situation is often reinforced by ambivalent feelings towards the violent partner (Anderson 2003; Enander and Holmberg 2008). In addition, other factors such as financial income, available or perceived external support and professional support play a significant role (Reisenhofer and Taft 2013). All of these elements can hinder the exit process. These phenomena are also found among men who are victims of IPV (Torrent 2003).

The exit can also be analyzed through the relationship breakdown as was done in Helfferich and his colleagues’ typology (Helfferich et al. 2005). Their first category, “Rapid Separation”, refers to women who have been in a relationship for a short time and have good self-esteem. The rupture occurs when the violence breaks their conception of the couple. Reconciliation is possible if a clear framework is defined within the couple. The second category, “Advanced Separation”, refers to victims in a longer relationship with chronic and gradual violence. The struggle to maintain the couple ends when the intensity of the violence exceeds what is bearable for them. After separation, these victims maintain a sense of fear towards their former partner. The third type, “New Chance”, considers victims who challenge their abusive partner through different behaviors. They hope to provoke a change and break the cycle of violence while maintaining the relationship. Finally, the fourth category, “Ambivalent Attachment” is characterized by the ambivalent position of female victims who oscillate between emotional dependence and fear (Helfferich et al. 2005). However, this typology does not deal with the mechanisms that could lead to these types of separation and is intended only for women victims of violence.

Processes of Getting out from Violence: What about Men?

While the victimization and exit from violence of female victims is well documented, the same is not true for men. In the seventeenth century the “beaten man”, the man who “let” himself be beaten by his wife, could be punished for failing to uphold his masculine condition (Vanneau 2006). Today, men can be considered as completely victims of domestic violence. Domestic assaults on men have been recognized in the literature since the 1950s, but Suzanne Steinmetz’s studies produced in the 1970s marked the beginning of academic research on this phenomenon (George 1994). According to Welzer-Lang (2009) male victims would “intentionally” take an inferior position towards women, a pattern of submission that can be observed in female victims of domestic violence. Welzer-Lang portrays these men as soft, inferior and dominated in different areas of their lives (Welzer-Lang 2009). Narrative studies conducted with male victims have highlighted different experiences. In “fatherhood stories” the man presents himself as a father, which is a socially acceptable identity for him, but also a factor of vulnerability. In narratives of the “good husband” he describes himself as a faithful husband for whom love justifies the continuation of a harmful relationship. “Victim stories” are characterized by terms signifying weakness and powerlessness. These stories are the result of a narrative shift from a dominant position to a more socially acceptable female position of victim (Kumar 2012; Corbally 2015). According to Jaillet and Vanneste (2017), this position reflects the dilemma of the man who physically belongs to the male population but whose history brings him closer to the female population. An “identity dissociation similar to denial, an extreme manifestation of the negation of the violence endured” (Jaillet and Vanneste 2017) can take root. This could prevent them from recognizing what they are experiencing and reacting to it. In other words, it seems even more difficult for a man to become aware of his victim status because it does not correspond to society’s definition of what “a man” or “a victim” should be. This has an impact on how he will perceive his experience and therefore his commitment to an exit process (Jaillet and Vanneste 2017). The purpose of this study then is to explore victims’ experiences of IPV, including female and male victims, and to examine the processes of getting out from violence.

The Present Study

The objective of this study is to understand the intrasubjective and intersubjective changes underlying the exit processes in victims of IPV, including male and female. The research project has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, Logopedics and Educational Sciences of the University of Liège, Belgium. The collection method was defined in consensus with professionals from a Belgian research group within the framework of the Federal IPV-PRO&POL research project (Belspo).2 We used a narrative approach based on a qualitative and inductive methodology (Rosenthal 1993) in the form of a semi-structured interview and a qualitative life calendar (Nelson 2010).

Method

Participants

The sample consists of 21 participants, 18 women and 3 men, experiencing or having experienced violence in heterosexual relationships. Participants were between 20 and 65 years old with an average age of 44.04 years. The shortest experience of violence, including post-separation violence, is one year and the longest is 34 years (X = 10.45 years). Nineteen of them had separated from their partner at time of the interview; two women were still with their violent husband. In one of these cases, there have been no violent confrontations for at least three years at the time of the interview. The longest time between leaving the violent relationship and the interview is 28 years, with an average of 6 years. Nineteen of the interviewees reported having been in a single abusive relationship. Two of the subjects reported violent experiences with different partners. All are Belgian residents and the majority are Belgian citizens but three participants did not hold Belgian citizenship.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through newsletters aimed at medico-psycho-social and judicial professionnals. Posters placed in various locations (doctor’s offices, police offices, etc.), social media (Facebook, forum) and word to mouth (with researcher professional and friendly acquaintances and snowball effect) allowed us to reach a potentially undetected population (people who were not part of a care system for violence between partners). These posts did not include any specific definition of IPV in order to collect the testimonies of all people who considered themselves victims. In order to be considered for inclusion in the study, participants had to be over eighteen years of age and had to have experienced violence or had been taken into care by an institution because of IPV on Belgian territory. All volunteer participants met the inclusion criteria. The semi-structured interviews were recorded using an audio recorder. Only one participant did not want to be recorded and note-taking by hand was done in this case. Interviews lasted one to four hours, averaging two and a half hours. To ensure that the interviews took place in the best possible conditions, they were conducted face-to-face in a private and quiet room. Rooms were reserved at the intermediary institutions (19.5%), libraries (9.52%) and the University of Liège (33.3%) while other interviews took place at the participants’ homes (38.1%). Before each interview, participants were reminded of the rules regarding confidentiality and anonymity. All gave their free and informed consent. All interviewees were informed via a consent form and verbally that they could end the interview at any time and change their mind about the use of their data, even after the meeting. Aware that the narration could confront participants with memories or to a current situation that are sources of suffering, the researcher shared contacts that could inform, listen to or help them if they felt the need after the interview. The researcher herself remained attentive to the difficulties expressed by the participants throughout and after the interview.

Interviews

Semi-Structured Interview

Trajectory studies facilitate the understanding of domestic violence as a process and provide a broad view of the experience (Band-Winterstein and Eisikovits 2014). We developed a semi-structured interview guide based on up-to-date literature and a life courses perspective. Through this semi-structured interview, participants could discuss, at their own rhythm, their representations and experiences of violence (« Can you speak about the relationship in which the violence occurred? », « What have been the impacts/consequences of this violence? »); how they perceived changes in the dynamics of violence and the process of leaving the violent relationship(s) (« Can you describe this (these) marital/family situation(s) at this time? », « If the violence stopped, can you tell me how it stopped? »); their needs in terms of intervention and disengagement from violence (« Did you receive help/assistance when things were not going well? », « Can you tell me about your help-seeking experience? ») and their opinion on public policies in Belgium (« What message(s) would you like to send to the political sector about domestic violence? »).

Qualitative Life History Calendar (LHC)

At the same time, participants used a Life History Calendar. This allowed them to place events in a more accurate temporality and helped in retrospective recall (Glasner and der Vaart 2009). Collecting data using the life calendar method permits understanding of the separation and resilience mechanisms and processes (Hayes 2016). Often used in its quantitative versions (Yoshihama and Bybee 2011; Kamimura et al. 2014), the method used in this study is a qualitative Life History Calendar (Nelson 2010). The calendar was constructed with the participant using a large sheet of paper and different coloured markers. Temporal domains and markers reflect the subject’s narrative. Rarely used in the qualitative form, this LHC allows for a dynamic analysis of violence by capturing the events and their sequencing, as well as the temporality of the events and the context in which they occurred. The combination of the semi-structured interview with a qualitative LHC is particulary revealing as we met people at different moments of their trajectory. The conjunction of the two methods supported the victims’ storytelling and allowed the researcher to adopt a temporal perspective in order to carry out a trajectory and process analysis.

Data Analysis Procedures

Narrative psychologists argue that « narrative construction is a popular human means of making sense of the world » (Murray 2000). Thus, the study of the narratives (i.e. « the story told ») appears ideally suited to understanding life upheavals and apprehending how individuals organize their perception, their evaluations of their social environment and their behaviors in a given environment (Murray 1997, 2000). A thematic (Paillé and Mucchielli 2016) and trajectory analysis was applied to the interviews. The thematic approach focuses « mainly on the whats of narrative » (Smith and Sparkes 2012), on what is fundamental in a narrative to apprehend an issue (Paillé and Mucchielli 2016). After word-for-word transcription and a first reading of the interview, the transcript was divided into “units of meaning”. These units are words, phrases or paragraphs that answer our research question. Codes, or themes, were then assigned to these units to describe their content. These themes mostly came from the participants’ transcripts. For example, for the unit « you feel like you’re stuck in something and you don’t know how to get out of it » (MB), we used the code “Feeling of being stuck”. Verbatim used in this paper to illustrate results are fragments of narratives, or units of meaning, translated from French to English. For each case, a thematic tree was created. The branching out of themes has been constructed using in parallel the individual life calendar to highlight temporality and trajectory. We structured main themes and emerging sub-themes chronologically from the meeting between partners to the total separation if there was one. Pre- and post-relation elements were also taken into consideration. This process allowed us to map out the trajectory of violence and exit from violence in stages. The transversal analysis of these stages then allowed for the formulation of a process considering the dynamics, experiences, subjective representations and changes underlying the leaving.

Maintaining the Integrity of Qualitative Methodology

We are conscious that our analyses reflect the subjects’ analysis of their own trajectory. The stages and subjective changes presented are the ones described by the victims. Thus, the thematic analysis was carried out from a phenomenological perspective. This practice expects the researcher to focus on the meaning that the subject gives to his/her narrative or, in other words, to encounter the subjectivity of the subject (Smith et al. 2009; Band-Winterstein and Eisikovits 2014).

Findings

Experiences of Violence

All subjects described multiple and cumulative forms of violence. The violence experienced are mostly psychological, physical and verbal. Cases of psychological violence mentioned by the interviewees included manoeuvers to deny the other person, to discriminate or discredit them through strategies of control, domination or surveillance. This violence differs from verbal violence because certain forms of psychological violence described by the victims did not involve a words or insults but rather an attitude, a behaving. These are the most frequently mentioned forms of violence. Acts of physical violence are the second most frequently mentioned by the female interviewees, but only one male interviewee referred to these acts. Verbal abuse, insults and denigration strategies are the third most common forms of violence mentioned by the interviewees. Verbal violence also include physical and death threats, sometimes with references to the use of a weapon.

To a lesser degree, the interviewees also referred to cases of economic violence, sexual violence and isolation. Whether male or female, victims saw less of their family and friends because the aggressor prevented them from doing so or because victims were ashamed to expose the dynamic of their couple. Sexual violence is also a common theme in inteviews with female participants, but also present in that of one man. This type of violence involves forced or unwanted sexual acts and is sometimes used to attack the psychological integrity of the partner. The way that economic violence are described by victims is more nuanced. Some women had no professional activity or worked with their husband, and it was logical, in their opinion, that their partner managed the couple’s finances. They did not have a bank account, and did not feel as though they needed one. For others, not having access to their own money was unacceptable or difficult to live with.

Another form of violence that, to our knowledge, has received less attention in the literature is linked to parenthood. Some male and female interviewees referred to various forms of violence that attacked their parental integrity. For example, a partner could turn children against the other parent. In this way, the children become “weapons”. This violence also prevented him/her from fulfilling his/her role as parent, such as when it came to giving an opinion on the children’s schooling. The victim is cast as never being good enough as parent.

Lastly, victims talked about post-separation violence that could take the same form as violence mentioned above. In some cases, they discussed institutional violence, relating either to how a violent partner used institutions against the victim or how the institutional system itself is perceived as violent.

All the victims mentioned that they experienced several forms of violence. In general, the violence was initially psychological and verbal. The acts of violence increased in intensity over time, sometimes becoming physical. Only one victim recounted how the threat of filing a police report for physical violence led to a change in her husband’s behavior who then limited his acts to psychological violence. For most participants, female and male, violence appeared in control or domination dynamics, for example, Mr. TB said that « to leave early in the morning to go [to work] she allowed me to do so and then towards the end I could no longer ».

The Process of Getting out from Violence

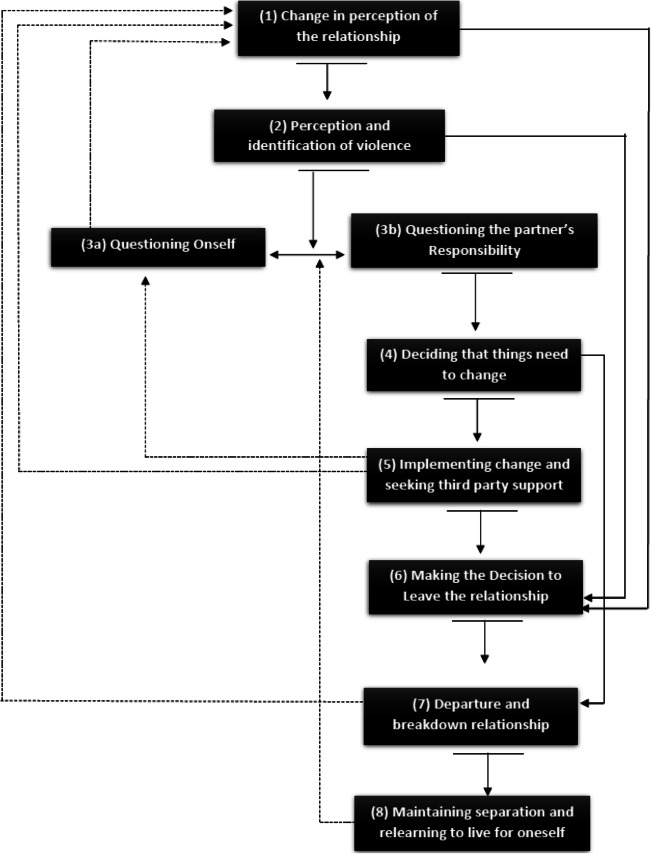

A thematic analysis of the 21 interviews highlighted eight sub-themes underpinning the process of getting out from a violent relationship: (1) Change in perception of the relationship; (2) Perception and identification of violence; (3a) Questioning oneself and one’s own responsibility; (3b) Questioning the partner and his/her responsibility; (4) Deciding that things need to change; (5) Implementing change and seeking third party support; (6) Making the decision to leave the relationship; (7) Departure and relationship breakdown; and (8) Maintaining separation and relearning to live for oneself.

Change in Perception of the Relationship

The interviews referred to an undefined moment in the trajectory that constitutes an upheaval in the relationship. A moment when victims looked at the relationship in a different way. This moment could appear few months after relationship began or several years later. The interviewees explained that this change occurred in response to a perceived change in the dynamics, the appearance of violence or an increase in the violence between partners.

« I had the impression that I was becoming more and more trapped...I realized that I didn’t recognize my ex-partner anymore and I started to question myself » (CD).

« It wasn’t any better because he started drinking more and more [...] but when he was sober he wasn’t so bad » (FG).

The three men’s stories depicted the same phenomenon. They express a sense of oppression, the feeling that they were the only one who dedicated themselves to the relationship.

« The situation was becoming burdensome » (AD).

« I felt oppressed » (TB).

Perception and/or Identification of Violence

The testimonies evoked a new reading of the situation, a reinterpretation of events as being violent. An act of physical violence or intense verbal abuse may have allowed for this identification to occur.

« I don't know exactly how it happened, but my brow bone hit the corner of the stairs [...] but that doesn't mean I reacted » (IR)

« When I got home, I told him how much I didn't like it. And then, he's 300 pounds, 6'3", he pushed me to the ground and he punched me and he broke my tooth » (GN)

In the stories of the three male victims, we noted perception of a form of manipulation or a suspicion of control strategies but no explicit recognition of violence.

« I didn't hear my alarm clock and it was Joy who changed the time so that I wouldn't have to go there [...] she needed me to stay with her, I don't know » (TB)

« I thought about manipulation and I thought, no, I'm the one who's making a fuss » (DB)

Narrations reflect two attitudes recounted by the victims. Regarding the first, victims expressed how they took all the responsibility and the second describes how they questioned the partner’s responsibility.

Questioning oneself and one’s Own Responsibility

The participants questioned themselves and developed different strategies to become, according to them, “as the partner wanted”. They adapted their behaviors or increased their benevolence.

« I'm going to become the one he wants me to be, and he's going to change » (FG)

« I saw it as a bit of a challenge, the more I was told that I wouldn't get anywhere with him, the more I convinced myself » (BB)

Notion of feeling responsible for the relationship were also present in the discourses of the three male victims as were the strategies for adjusting to the partner in order to avoid being confronted with what they feel or recognize as violent.

« I'm the one who said well I'm still going to try to save my couple » (TB)

« I felt like I was hurting her, that I wasn't normal, that I was the one who […] yes, it was me who was making her unhappy » (AD)

Victims could also take another position where they questioned the role of the partner.

Questioning the Partner and their Responsibility

At this moment, the participants perceived a change in their partner and subsequently questioned their parnter’s own responsibility.

« I saw, I felt, his real nature. “Now you're mine, you're going to do what I want” » (FG)

« He used psychological violence…really I felt it at that time […] he scares me » (GN)

The notion of fear in the women’s discourse rarely appeared in the discourse of the three male victims. The attribution of responsibility to their spouse followed an affront that exceeds their threshold of tolerance.

« She didn't realize I'd actually moved to another country. That's when I realized how uninterested that person was in what I did » (DB)

« I'd basically have to follow her and if I didn't she'd fly into a rage... » (AD)

Deciding that Things Need to Change

This theme relates to how victims mobilized changes to end violence in their relationships. These changes involved a departure or a confrontation. In this way, they hoped for a change on the part of the partner. Therapy for violent people, couple therapy, individual therapy or seeking support from family and friends were all mentioned by the victims.

« I told him, listen, how about we see a psychologist? I said, listen, I’m going to leave you, I can’t take it anymore. Either you change, or I’m leaving » (FL)

« After a certain number of years, I figured I’m not going to end up with him anyway » (MD)

It appears that this decision to change was, for two of the men, partly dependent on a meeting with a friendly or intimate third person who became a support person. For the last one, it was not a question of reaching out to a third person but rather of becoming one’s own supporter.

« It had actually been two years after I kissed my co-worker that I said to myself I might be getting a divorce » (TB)

« I thought, but it's my birthday, it should be me who... I should be the one to decide » (AD)

Implementing Change and Seeking Third Party Support

This change manifests through different initiatives on the part of the victims or their entourage. They seek out psychological support, couple therapy or contact the police one or several times in the hope that this will provoke an electroshock or punish the partner. The aim is not, at this stage, to end the relationship but to end the violence.

« I called [my parents], but not to leave. [...] they took me aside and they said you're not staying here anymore, I wanted to stay, I didn't want to leave » (FG)

« The psychologist […] he made me understand that. […] And he told me at one point, ‘be careful because you're vulnerable’ » (VH)

The male interviewees did not mention filing police reports, but one did refer to taking part in couple therapy and another sought out ‘one night stands in order to put up with situation at home.

« We also tried to set up with my wife couples’ therapies twice; my wife stopped each time in a unilateral way » (TB)

« I [had] a drink with [other people][...] but I never said I slept with them in the end. It made me feel better about living that [girlfriend’s] hold » (DB)

Making the Decision to Leave the Partnership

For some victims, the perception of an alteration in the couple dynamics could be sufficient to trigger the decision to end the relationship. However, other narrations emphasized that this process was initiated only after perceiving the violence and partner’s responsibility, which notably occurs after an intense episode of violence, an act that threatens the victim’s life or an unforgivable betrayal. A change is inconceivable or has been initiated but without result. Beyond the decision-making balance, which is central in the discourses, the decision to leave a violent relationship involves many affective procedures on the part of the victims. While some victims explained that they took legal precautions by preparing a file of evidence, others said that they gradually distanced themselves, physically or emotionally, from their partner. The decision to separate involves many questions and new internal conflicts with which they had to deal.

« I told myself “I'm not happy with him, I have to leave him”. I don't know how to explain that. But I would never have known how to leave him. I was too much in love with him » (LB)

« I'm staying because of the house, I've put all my life into it, all my money in there and I’ve worked in the house all this time » (RK)

Only one of the three men had prepared his departure before break-up.

« I went to see my accountant to know the impact of a divorce on my self-employed status. I went to a lawyer one year ago and said “well, how much does a divorce cost?” » (TB)

Departure and Relationship Breakdown

Leaving is the realisation of a physical separation. It can be prepared or spontaneous, depending on the occasion or the “trigger”. It can mean the end of the abusive relationship but can also be part of a larger departure process with “back-and-forth” phenomena.

« Instead of pulling my car in, I backed up, I drove off and never came back. With nothing, just like that, I left » (MD)

« And that's when I said no, I don't want this anymore [...] I won't anymore » (LC)

For the three male victims who testified about their experiences, it was the untenable nature of the situation that triggered the departure.

« And now I see nudes pictures she sent [...] So there was no excuse [...] So I took my things, I went home » (DB)

« I had a scare; I told myself if I stay […] I felt like a trap was going to close forever » (TB)

Maintaining Separation and Relearning to Live for oneself

Leaving does not always mark the end of violence. A majority of victims reported having experienced post-separation violence. This is physical violence, harassment or the instrumentalization of children. In addition to these, violent ex-partner may also use a form violence that is rarely deployed during the relationship: the instrumentalization of institutions in order to discredit or hurt the victim. These violence will encourage victims to leave or, on the contrary, frighten them and make them doubt. So they will confirme their decision of departure or return with the fromer-partner. Some victims still expressed ambivalent feelings about their former partner after separation. Conscious about the risk of returning to the ex-partner, many of the interviewees referred to surrounding themselves with professionals or their family. The aim is to tolerate life after the relationship or learn to live – again – for themselves.

« I was always hiding from […] my parents, because I didn't want them to know because I thought if I went back to him, my parents wouldn't let me » (MBF)

« You fasten yourself to the heater with a pair of handcuffs so that you don't move, and the phone, you want to break it to make sure you don't call [him] » (MB)

In the same way, it was not easy for the three men to leave their girlfriends for good.

« She would do anything to catch up with me [...] so that I would stay » (AD)

« I still wanted to forgive her. But I figured it's the best time to leave and start something with someone else » (DB)

All victims, men and women, who ended the violence within the couple differentiate between “being a victim” and “having been a victim of violence”. This status of victim leads to multiple viewpoints. Some consider themselves as victims of post-separation violence, while some who experience similar types of post-separation violence do not. Others raise the question of their responsibility and do not position themselves entirely as victims. Some interviews showed how victims progress from being victims to being ex-victims. They take a position where they are aware that they have suffered violence, but they no longer consider themselves as victims.

« I'm a victim, that's true, but it took a long time for me to recognize it because I didn't want to recognize that I was a victim » (IR)

« Domestic violence I referred to it as such only ten days ago. Cos I went to a police victim services unit » (TB)

Discussion

The process of getting out from an abusive relationship is primarily conditional on changes in « the subjective meaning of the situation » (Anderson 2003). The analysis of the 21 semi-structured interviews and qualitative LHQ made it possible to highlight different phases of the process (See Fig. 1). Each phase implies personal and/or interpersonal steps made towards a change in terms of perception, recognition and integration of a situation. The results confirm that, beyond the major contextual and structural constraints, victims’ representations of themselves, of their patner or of the violence endured will have a significant impact on the process of getting out from the violence. Victims’ trajectories contain similar steps nuanced by individual and environmental specificities for both female and male. However, the small number of male victims calls for caution regarding these results and studies involving a larger sample size will be necessary.

Fig. 1.

Schematization of the process of getting out from intimate partner violence

According to Welzer-Lang’s model, mentioned in Torrent’s study (2003), a decision must first be taken for action to occur, which is itself preceded by reflection. This reflection takes place following an increase in the intensity of the violence, which leads the victim to become aware of it (Chang et al. 2010). Our analyses show that the process of getting out from violent relationship begins when the victim perceives a change in dynamics within the couple (See Fig. 1, item 1). The appearance of or an increase in violence, particularly in control mechanisms deployed by the violent partner, may be not perceived but felt by victims. What they later perceived as control mechanisms is then a feeling or an impression. It is like « something uncomfortable » (IR) that comes from of the relationship or partner. The initially idealised image of the intimate partner wavers but that doesn’t make him/her a “violent person”. They are rather « angry » (MD), « not happy » (FG) or « never satisfied » (BB). In the couple, a dynamic is established that victims can compare to a conflictual dynamic where disputes between partners multiply. The perception of responsibility is, at this stage, oriented outwards. Victims will consider, for example, that the dynamic has changed because the other partner is depressed, unemployed or because he or she reproduces a family pattern. A husband’s consumption of alcohol – there is no mention of any excessive consumption in men victims’ speeches – is sometimes the only objectively observable phenomenon that allows the victim to rationalise an internal tension « [He had] “Bad alcohol”, he drank whisky, so it was infernal » (FG). From that moment onwards, some victims understand that this is not acceptable and take steps in preparation of leaving the relationship. The vast majority, however, is confronted by incomprehension. They develop strategies to reduce this state of internal tension generated by the change in the relationship dynamics (Burman 2003; Estrellado and Loh 2019). This may contribute to the strengthening of the partner’s hold over the victim.

This state of internal tension may lead to another phase in the getting out process, which no longer implies a feeling but a discernible cognitive mechanism for perceiving violence (See Fig. 1, item 2). At this stage, the expression of feelings will be a secondary element of the interviews. For a large majority of our participants, the narration is primarily focused on the lived facts. On the other way, some victims clearly expressed that they were not, at that time, afraid of their partner but they became aware that they were in a position of weakness in relation to them. Acts that were not understood at the previous stage become recognized as violent. This does not always imply the recognition of this violence as partner violence or as a process of domination. It is important to clarify several elements at this level. On the one hand, we have to differentiate the qualification of an act of violence and the qualification of the partner or the relationship as violent. On the other hand, acknowledging violence does not necessarily make the victim feels like a victim. Moreover, recognizing oneself as a “victim of” is not essential to starting the getting out process (Enander and Holmberg 2008; Sita and Dear 2020). Some victims will consider leaving the relationship at this stage of the process.

Then, we observe two attitudes in these victims. They may question their own roles in the establishment of the violent dynamic (See Fig. 1, item 3a) or question the partner’s responsibility (See Fig. 1, item 3b). The sooner they perceive and acknowledge the partner’s violence, the sooner they can decide to leave. Taking responsibility for the situation generally leads to attempts at changing one’s behaviors to maintain the couple. This attitude is close to what Torrent (2003) calls « the hope of sustained change » and the belief of “I will change him/her”. The victim develops coping strategies such as self-protection, over-investment and self-improvement (Torrent 2003). Consciously or unconsciously, they act as guarantor for the couple or partner (Anderson 2003). This makes it possible to understand how interventions of the victim’s friends and family can be, at this stage, ignored or manifestly rejected by the victim. External interventions could be experienced as coercion, criticism against themselves or a challenge « I’m going to prove it to them » (BB). In another way, attributing responsibility of the violence to the partner implies different mechanisms of understanding that can differ somewhat between men and women. Men do not fear their wives in the same way (Sita and Dear 2020). What women victims consider, a posteriori, as control or domination were experienced and expressed as a feeling of fear towards the partner. For example, the feeling of being « a mouse for a cat » (GN). Women in violent relationships are more afraid of their husbands whereas men are afraid of spouses’ violence but less so from the spouses themselves (Hamberger and Guse 2002; Archer 2002). Indeed, the three male subjects’ attribution of responsibility their partner occurred when their partner exceeded their already low threshold of tolerance. This is different from perceiving the partner as violent, as having committed an act of violence or the violence as serious. Some victims will justify the assault by blaming it on depression, jealousy or a lack of communication skills what can be understood as an attempt to create meaning and a sense of coherence in a traumatic situation (Enander and Holmberg 2008). It should be noted that these responsibility attribution manoeuvres (see Fig. 1, items 3a and 3b) may follow one another or coexist simultaneously. For a more or less long period of time, a balancing movement occurs between these two positions. Taking position can be all the more difficult because while victims are attributing responsibility, they may also be confronted with feelings of shame or guilt. Shame for « having fear » (IR), « having let oneself » (AD) be a victim or for « failing something » (AD) in the relationship. However, it is mainly during the “questioning partner phase” that a move towards the next phase of the process seems most likely to occur. This finding is in line with Keeling’s work (Keeling et al. 2016) which shows that when there is a perception of risk, victims’ perceptions of their partner change. If they are not ready to act at this stage, they may at least preventively realize the importance of leaving the relationship (Keeling et al. 2016). While some victims will escape at the first act of violence others will stay and resist actively or passively (De Vinck 2004).

Acknowledging violence and partner’s responsibility thus opens the door to another turning point in the process of getting out from violence: the decision that a change is essential (See Fig. 1, item 4). Anger seems to initiate a change in the victim’s position towards his/her couple and his/her partner. Some interviewees mentioned a form of rebellion when they no longer accept the situation as it was. Thus, victims develop different strategies. Physically leaving is one of them, but it is not the only one. There are also manoeuvres to safeguard the relationship. This stage is a significant moment when assistance, whether requested or offered, seems to be an option that the victim – and sometimes even the perpetrator – is willing to consider. They turn to those around them. First, their family, which is often a valuable resource. When family and friends are not present, or when the victim does not want ask them to help, the Internet can also provide support to find testimonies, addresses or numbers of support services.

Then, the change is put into action (See Fig. 1, item 5). Our analyses underline strategies close to the categories identified by Helfferich and his colleagues known as “advanced separation” and “new chance” (Helfferich et al. 2005). Subjects regain control of the situation by adopting various behaviors: by engaging in seeking psychological support, by establishing a clear framework and limits within the couple, or to a lesser degree through physically or verbally violent behaviour. As in Anderson’s work (Anderson 2003), our results underline the fact that, in the process of getting out from a violent relationship, victims are active (Anderson 2003). This phase is tinged with doubt and shame. It is not easy to admit to oneself and others that a relationship is dysfunctional or violent (Thaggard and Montayre 2019). Enander and colleagues (Enander and Holmberg 2008; Enander 2011) described how the emotions as love, fear, guilt or hope create a “traumatic bond” that indeed binding victims to their abusers (Enander and Holmberg 2008; Enander 2011). At this stage, if the change is permanent, the relationship can see a decrease or even a complete stop to the violence and the victim may decide to stay with the partner, although this is not always definitive. When there is no change, leaving can be considered. Once again, the family is an important resource along with various professionals. Family or community values may represent a barrier to or a support for victims seeking to end an abusive relationship (Lefaucheur et al. 2012). This is also a crucial moment for the care of victims of violence. It appear that with helpfull contact from professionals or personal entourage other parameters in the process of getting out from a violent relationship will come into play, including the recognition of IPV and the decision to leave. Conversely, a lack of support, a judgmental attitude or lack of knowledge on the part of clinicians prevent help-seeking efforts (Reisenhofer and Taft 2013).

The decision to leave (see Fig. 1, item 6) may occur at different moments in the violent relationship. The sample subjects who separate early fit with the “rapid separation” category of Helfferich et. al’s typology. In contrast, long-term relationships with a late decision to leave reflects the “ambivalent attachment” category. In this kind of relationship the dynamic is often marked by the victims’ violent childhood experiences which reflected in the relationship (Helfferich et al. 2005). Indeed, assertiveness, capacities for action and abilities to make strategic life choices, is a non-linear process that build on lifelong learning and evolves throughout the relationship (Schuler et al. 2018). Similarly, our analyses reveal that life experiences which promote empowerment not only prevent partner violence but appear to be factors that can precipitate decision making. At this stage, fear and anger seem to play a central role. A high level of anger can encourage the decision to leave an abusive relationship (Reisenhofer and Taft 2013; Keeling et al. 2016). Fear of the partner can also be a trigger, especially when it concerns fear for one’s life (Catallo et al. 2013). Our analyses point out that fear can increase because the victim is afraid that the prospect of leaving will lead to an intensification of the violence but it can also decrease because the victim knows that she is regaining control of their life. Children are another significant element that need to be taken into account regardless of whether the victim is the mother or father. Violence inflicted by one partner on the other can reach the children and become a risk for them. One of our findings highlights a particular form of violence where children become indirect “actors” of violence when they are instrumentalized by one of the parents, thus become both victims and weapons to hurt the other parent’s integrity. The perspective of remoteness can create additional fear in the decision-making process for the victim. A legitimate fear since infanticide represents a real risk in the case of separation (Dawson 2015). When this is perceived by the victim, it may mark a turning point in the decision to leave (Catallo et al. 2013). Children can also hasten the end to a violent relationship when they question or support the parent victim of violence. In another way, they can be a barrier when they refuse to follow the victim or because the victim does not want to deprive the children of a family.

At this point, a more or less defined plan to leave the relationship is conceived. Victims prepare the departure and post-departure life by contacting professionals or entourage to find help, shelter, security and support. For those whose family or friends are perceived as supportive, they become the main resource to carry out the necessary procedures. Help services and shelters appear as sources of support when they are known and their usefulness is recognized by the victims. And then, there is the moment of departure (See Fig. 1, item 7). The departure depends on the opportunity or the “trigger”, when spending another minute with the partner is no longer bearable or, at that moment, too dangerous. The “trigger” marks « a clear break in the trajectory of acceptance of violence » (Lefaucheur et al. 2012). This intrinsic phenomenon marks the end of the empathy shown towards the partner and accelerates the departure (Lefaucheur et al. 2012; Reisenhofer and Taft 2013). Changes in emotions, such anger, contribute to this momentum (Enander and Holmberg 2008). The moment of departure may come in a moment of extreme fear and anger that triggers the break-up. The analysis of the victims’ experiences makes it possible to question this notion of a trigger. Our results show that this trigger is part of a mechanism that modifies not only the perception of the violence but of the relationship and oneself too. The subjects may perceive themselves as victims of IPV or recognize the relationship as unbearable for themselves. Anderson (2003) similarly points out that studies of the exit process reveal that most vicitms report a sudden but often gradual change in perspective where they define the relationship as abusive and themselves as victims. Thus, the recognition of violence as IPV seems to be a mechanism in its own right that may or may not be part of the process of getting out from violence. The police can play a fundamental role in this stage (Begon 2009). They should be a relay towards freedom, they should provide material and moral supports, information on violence between partners – thus confirming or not the victim’s feelings – and, more than anything else, provide security. A positive meeting between police and the victim does not guarantee a definitive departure but can encourage recognition of IPV and thus hasten an end to the relationship. When the police do not provide the help expected by the victim, it seems all the more difficult to realize that the situation experienced is not acceptable and diminishes the chances of change whatever the stage at which the police is called in.

The last stage of this process (See Fig. 1, item 8) is similar to those frequently highlighted by other process studies called “self-restructuring” (Mills 1985) or “pursuing one’s life” (Wuest and Merritt-gray 1999). There is an identity shift where the person leaves the identity of “victim” behind to invest in a new life and regain a new sense of “self” (Wuest and Merritt-gray 1999). Before regaining this sense of “self”, they must identify themselves as a victim of domestic violence. Similar to the recognition of IPV, it is through contact with family, friends and professionals that this change seems to occur. If concerned people have already perceived and acknowledged that they were victims of problematic marital dynamics, they are now be able to assimilate that they are, or have been, victims of IPV (Enander and Holmberg 2008). However, this recognition is not easy, since victims sometimes feel ashamed and guilty for having “inflicted” this on themselves or “inflicted” this on those around them (Offermans and Kacenekenbogen 2010). Some victims blame themselves while acknowledging the hold their spouse had over them. Moreover, recognition does not protect them from fear or ambivalent feelings towards the partner and a new state of internal tension. This may lead them to reconsider their role, the role of their former partner in the relationship dynamic and the departure. Indeed, if this getting out process is presented in a linear way for ease of reading it takes into consideration back-and-forth phenomena. Moreover, according to the model proposed, the ending of violence does not necessarily imply leaving or breaking up. Departure is considered as a part of the getting out process but not as an end in itself. The processus of getting out from a violent relationship combines different subjective and intersubjective changes. Leaving a relationship or bringing an end to the violence within that relationship involve a set of decisions made in response to different identification phenomenon. A sequence of changes in the perception of self, partner, couple and violence will allow for multiple cognitive and relational transitions.

Limits and Perspectives

This research has shed light on the process of getting out from intimate partner violence by analysing 21 semi-structured interviews carried out with 18 women and 3 men. However, the overwhelming majority of people who responded to our call were Caucasian women, from middle socio-economic class and who had experienced violence in heterosexual relationships. Future research may address the issue of getting out process in minority populations, the LGBTQI+ community, people in a precarious or in a migratory situation. Intersectional methodological approaches may highlights the complex interactions of sociocultural and individual factors that could affect decisions to leave (Barrios et al. 2020).

The results of our study have highlighted characteristics that are similar to those found in desistance studies and in particular the concept of secondary desistance (Farrall and Maruna 2004). If primary desistance describes a process of disengagement from violence, secondary desistance refers to a process in which the subject no longer defines him/herself as “an offender”. This process is only possible through a combination of social, contextual and cognitive elements (Farrall and Maruna 2004; Giordano et al. 2015; Walker et al. 2017). Both concepts presuppose a non-linear process of change with multiple factors specific to each individual and in which there are identifiable phases that promote or prevent desistance. This change may begin within the couple even before treatment is initiated (Walker et al. 2015). Emotional responses, changes in perception, social factors and life context appear to be fundamental in initiating a change for victims and perpetrators’ getting out from violence process (Meyer 2016; Walker et al. 2017). Further studies of the similarities between these processes would allow us to learn more about the interpersonal mechanisms involved in desistance and “exit” from IPV as well as if – and how – these processes interact to promote the end of violence between partners.

Undertaking the process of getting out from violence is only possible through a combination of cognitive, interactional, contextual and social elements. Targeting which phase of the process the victim is in – as for the perpetrator – appear central to any care system. The development of clinical intervention must be able to take into account the victims’ level of recognition of the situation they are in. If it is understood that leaving remains an important objective to ensure the victim’s safety (Reisenhofer and Taft 2013), the clinician will have to consider, first and foremost, the mechanisms of perception and understanding developed by victims. Clinical interventions should focus on the acknowledgement of violence and its inadmissibility before departure is counselled. Otherwise, there is a risk of creating a conflict between the person’s internal discourse and a contradictory external discourse.

Although the small number of male victims who responded to our request for participation does not allow us to make statements, the process of acknowledging violence seems even more challenging for men. It will be interesting to investigate the notion of fear in a larger sample of IPV male victims. The notion of fear has already been linked to the realization that leaving a relationship is crucial to survival in women (Keeling et al. 2016); it would be interesting to study how fear plays a role for male victims. For men, the role of stakeholders, but also of society in general, would be all the more important to promote recognition of their status as victims of violence (Torrent 2003). Nevertheless, at the time of writing, the world is in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic that is forcing one third of the global population into confinement. This event has brought to light the condition of victims who are forced to remain confined with their persecutors (Guenfound 2020; Davies and Batha 2020). During this period, we have seen that the Belgian media has paid increasing attention to domestic violence. For the victims, help seeking and support measures, including social recognition, have been multiplied (Gerster 2020; Guenfound 2020). Moreover, even if women remain the first victims of IPV, it is important not to neglect men who are victims of such violence (Warburton and Raniolo 2020). Society participates structurally in the maintenance of violence by safeguarding the taboo surrounding male victims while stigmatisation is fundamental for a person who must attain the status of victim to be able to overcome it (Torrent 2003). This is essential in terms of secondary prevention, but it must also be thought of in terms of primary prevention. The assertiveness, that is the ability to make choices, identify them and to have them respected is a process that is based on a lifetime of learning through contact with others (Lefrançois et al. 2011; Schuler et al. 2018). Making it possible to recognize IPV regardless of age, sex or status of the partners from the earliest age must become a central concern of prevention policies in this domain. Moreover, this ability to make strategic choices also evolves throughout the conjugal relationship. All the people we met have had different experiences of violence. Nevertheless, the objectives of this study do not allow for the comparison of particular dynamics of violence with specificities in the process. A better understanding of the processes of getting out from relationships with different violent dynamics such as intimate terrorism, situational violence (Johnson 1995) or even bi-directional violence should be considered for future research. This will be all the more important in order to adapt care for victims, for both female and male.

The three men testify to a constructive intervention which enabled them to overcome their shame and to participate in our study. Reaching a population of male victims with other experiences would deepen our understanding of the subjective changes at play in their exit trajectories. Even more so because after separation, if men and women are subjected to further violence by the ex-spouse, it appears that institutions can also be vectors of difficulties (Reisenhofer and Taft 2013) or violence, as one woman said clearly « we are in institutional violence » (CD). As the victims in our sample testify, this violence is often carried out through lengthy, costly and opaque procedures, or simply because the judicial system places huge expectations on people who are often particularly vulnerable. Many victims point to the lack of information on what to do before, during and after violence and how to deal with it, which can slow down the getting out from violence process. Thus, wider knowledge of the possibilities and support services available to them could play a specific role in this process. It is not only a question of being informed about IPV. It is necessary to be able to assess communication gaps and to give people, who may one day be part of a care system, tools to understand it. Beyond the knowledge of available ressources, how victims perceive the usefulness of them may be another factor worthwhile examining in greater depth for the development of interventions and public policies in the domain of IPV.

Conclusion

The study of the narrations of violence between partner victims remains a major challenge for understanding the dynamics of violence and the getting out process. This study emphasizes that subjective changes in the perception of the relationship, the partner and oneself can lead to an awareness of the relationship’s problems and to a decision of getting out from it. If some events appear to be triggers for leaving, the actual processes at work involve multiple levels alternating between perceptions of risks, attribution of responsibility, and re-evaluations of oneself and the relationship. Furthermore, the recognition of partner violence and victim status appear to be a necessary but not an obligatory condition to initiate an exit. Thus, stakeholders must be able to assist the getting out process by aligning their intervention strategies with the victims evolution.

Funding

The study presented is part of the Belgian federal research BELSPO.brain « Intimate Partner Violence: Impact, Processes, Evolution and Related Public Policies in Belgium » (IPV-PRO&POL).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

None.

Footnotes

Law of 24 November 1997, “Loi Lizin”, Law to combat violence within the couple.

Belgian federal research BELSPO.brain « Intimate Partner Violence: Impact, Processes, Evolution and Related Public Policies in Belgium » (IPV-PRO&POL).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amandine Dziewa, Email: Amandine.Dziewa@uliege.be.

Fabienne Glowacz, Email: fabienne.glowacz@uliege.be.

References

- Ali P, McGarry J. Supporting people who experience intimate partner violence. Nursing Standard. 2018;32(24):54–62. doi: 10.7748/ns.2018.e10641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. Evolving out of violence: An application of the Transtheoretical model of behavioral change. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2003;17(3):225–240. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.17.3.225.53182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2002;7:313–351. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(01)00061-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Band-Winterstein, T., & Eisikovits, Z. (2014). Intimate violence across the lifespan. New York, NY: Springer New York.10.1007/978-1-4939-1354-1.

- Barrios, V. R., Khaw, L. B., Bermea, A., & Hardesty, J. L. (2020). Future directions in intimate partner violence research: An Intersectionality framework for analyzing Women’s processes of leaving abusive relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Begon, R. (2009). 2006–2009: les COL 3 et 4 trois ans après. CVFE-publication. Retrieved from http://www.cvfe.be/sites/default/files/doc/EP2009-8-EvaluationCol4-Partie1-Rene.pdf

- Brillon P, Marchand A, Stephenson R. Modèle comportementaux et cognitifs de stress post-traumatique. Santé Mentale au Québec. 1996;21(1):129–144. doi: 10.7202/032383ar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Denison JA, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. Ending intimate partner violence: An application of the Transtheoretical model. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28(2):122–133. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.28.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Mahoney P, Gielen A, McDonnell KA, O'Campo P. Defining appropriate stages of change for intimate partner violence survivors. Violence and Victims. 2009;24(1):36–51. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman S. Battered women: Stages of change and other treatment models that instigate and sustain leaving. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2003;3(1):83–98. doi: 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhg004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catallo C, Jack SM, Ciliska D, MacMillan HL. Minimizing the risk of intrusion: A grounded theory of intimate partner violence disclosure in emergency departments. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013;69(6):1366–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Dado D, Ashton S, Hawker L, Cluss PA, Buranosky R, Hudson S. Understanding behavior change for women experiencing intimate partner violence: Mapping the ups and downs using the stages of change. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;62:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Dado D, Hawker L, Cluss PA, Mcneil M, Scholle SH. Understanding turning points in intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(2):251–259. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluss PA, Chang JC, Hawker L, Hudson Scholle S, Dado D, Buranosky R, Goldstrohm S. The process of change for victims of intimate partner violence. Support for a psychosocial readiness model. Women's Health Issues. 2006;16(5):262–274. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbally M. Accounting for intimate partner violence: A biographical analysis of narrative strategies used by men experiencing IPV from their female partners. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30(7):3112–3132. doi: 10.1177/0886260514554429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbeil C, Marchand I. Penser l’intervention féministe à l’aune de l’approche intersectionnelle. Défis et enjeux. Nouvelles pratiques sociales. 2006;19(1):40–57. doi: 10.7202/014784ar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE. “The strongest women”: Exploration of the inner resources of abused women. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12(9):1248–1263. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S., & Batha, E. (2020). Europe braces for domestic abuse ‘perfect storm’ amid coronavirus lockdown. Thomas Reuters Foundation news. Retrieved from: https://news.trust.org/item/20200326160316-7l0uf

- Dawson M. Canadian trends in filicide by gender of the accused, 1961–2011. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;47:162–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieu E, Hirschelmann A. Intervenir dès le signalement: analyses victimologiques du protocole interpartenarial de lutte contre les situations de violence conjugale (France) Annales Medico-Psychologiques. 2017;176(4):327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.amp.2013.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enander V, Holmberg C. Why does she leave? The leaving process(es) of battered women. Health Care For Women International. 2008;29:200–226. doi: 10.1080/07399330801913802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enander V. Leaving Jekyll and Hyde: Emotion work in the context of intimate partner violence. Feminism & Psychology. 2011;21(1):29–48. doi: 10.1177/0959353510384831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Estrellado AF, Loh J. To stay in or leave an abusive relationship: Losses and gains experienced by battered Filipino women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(9):1843–1863. doi: 10.1177/0886260516657912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrall S, Maruna S. Desistance-focused criminal justice policy research: Introduction to a special issue on desistance from crime and public policy. The Howard Journal. 2004;43(4):358–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2311.2004.00335.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ. Riding the donkey backwards: Men as the unacceptable victims of marital violence. The Journal of Men's Studies. 1994;3(2):137–159. doi: 10.1177/106082659400300203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano P, Johnson W, Manning W, Longmore M, Minter M. Intimate partner violence in young adulthood: Narratives of persistence ans desistance. Criminology. 2015;53(3):330–365. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner T, der Vaart V. Applications of calendar instruments in social surveys: A review. Quality and Quantity. 2009;34(3):333–349. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerster, J. (2020). When home isn’t safe: How coronavirus puts neighbours on front lines of abuse. Global news. Retrieved from: https://globalnews.ca/news/6723582/coronavirus-domestic-abuse/

- Guenfound, I. (2020). French women use code words at pharmacies to escape domestic violence during coronavirus lockdown. ABC news. Retrieved from: https://abcnews.go.com/International/french-women-code-words-pharmacies-escape-domestic-violence/story?id=69954238

- Hamberger LK, Guse CE. Men's and Women's use of intimate partner violence in clinical samples. Violence Against Women. 2002;8(11):1301–1331. doi: 10.1177/107780102762478028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes BE. Impact of victim, offender, and relationship characteristics on frequency and timing of intimate partner violence using life history calendar data. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2016;53(2):189–219. doi: 10.1177/0022427815597038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heim EM, Trujillo Tapia L, Quintanilla Gonzales R. “My partner will change”: Cognitive distortion in battered women in Bolivia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018;33(8):1348–1365. doi: 10.1177/0886260515615145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfferich, C., Lehmann, K., Kavemann, B., & Rabe, H. (2005). In: Bureau fédéral de l’égalité entre femmes et homme (2012). Rapport final: La spirale de la violence: typologies des auteur∙e∙s et des victimes: conséquences pour le travail de consultation et d’intervention, 6. Retriewed from https://www.fr.ch/sites/default/files/contens/bef/_www/files/pdf50/Spirale_violence_2012.pdf

- Hendy HM, Eggen D, Gustitus C, Mcleod KC, Ng P. Decision to leave scale: Perceived reasons to stay in or leave violent relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27(2):162–173. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert TB, Silver RC, Ellard JH. Coping with an abusive relationship: How and why do women stay? Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53(2):311–325. doi: 10.2307/352901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillet M, Vanneste C. Violence entre partenaires et victimisation masculine: d'une réalité cachée au parcours du combattant personnel, social et institutionnel. Revue de la Faculté de Droit de l'Université de Liège. 2017;2:267–303. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:283–294. doi: 10.2307/353683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura K, Bybee D, Yoshihama M. Factors affecting initial intimate partner violence–specific health care seeking in the Tokyo metropolitan area, Japan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29(13):2378–2393. doi: 10.1177/0886260513518842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling J, Smith D, Fisher C. A qualitative study exploring midlife women’s stages of change from domestic violence towards freedom. BMC Women’s Health. 2016;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0291-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug, E. G., Dahlberg, L. L., & Mercy, J. A. (2002). Rapport mondial de la violence et la santé. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Genève. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/ world_report/en/full_fr.pdf.

- Kumar A. Domestic violence against men in India: A perspective. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2012;22(3):290–296. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2012.65598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur N, Kabile J, Ozier-Lafontaine L. Itinéraires féminins de sortie de la violence Conjugale. Pouvoir dans la Caraïbe. 2012;17:197–236. doi: 10.4000/plc.868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrançois C, Van Dijk A, Bardel MH, Fradin J, El Massioui F. L’affirmation de soi revisitée pour diminuer l’anxiété sociale. Journal de Therapie Comportementale et Cognitive. 2011;21(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcc.2010.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mélan, E. (2017). Violences conjugales et regard sur les femmes. Champ pénal, 14. 10.4000/champpenal.9574.

- Meyer S. Still blaming the victim of intimate partner violence? Women’s narratives of victim desistance and redemption when seeking support. Theoretical Criminology. 2016;20(1):75–90. doi: 10.1177/1362480615585399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills T. The assault on self: Stages in coping with battering husbands. Qualitative Sociology. 1985;8(2):103–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00989467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. A narrative approach to Health Psychology: Background and potential. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(1):9–20. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. Level of narrative analysis in health psychology. Journal of Health Psychology. 2000;5(3):337–347. doi: 10.1177/135910530000500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AN. From quantitative to qualitative: Adapting the life history calendar method. Field Methods. 2010;22(4):413–428. doi: 10.1177/1525822X10379793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Offermans, A. M., & Kacenekenbogen, N. (2010). La prévalence des violences entre partenaires. Pourquoi la détection par le médecin généraliste ? Revue médicale de Bruxelles, 31(4), 415–425. oai:dipot.ulb.ac.be:2013/151115; http://hdl.handle.net/2013/ULB-DIPOT:oai:dipot.ulb.ac.be:2013/151115. [PubMed]

- Paillé, P. & Mucchielli, A. (2016). L'analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales - 4e éd. Armand Colin.

- Pieters, J., Italiano, P., Offermans, A. M., & Hellemans, S. (2010). Les expériences des femmes et des hommes en matière de violence psychologique, physique et sexuelle. Institut pour l’égalité des femmes et des hommes. Bruxelles. http://hdl.handle.net/2268/62418

- Reisenhofer S, Taft A. Women’s journey to safety – The Transtheoretical model in clinical practice when working with women experiencing intimate partner violence: A scientific review and clinical guidance. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;93(3):536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, G. (1993). Reconstruction of life stories: Principles of selection in generating stories of biographical interview. The narrative study of lives, 1(1), 59-91. http://nbn-resolving.de/ urn:Nbn:de:0168-ssoar-59294.

- Schuler S, Field S, Bernholc A. Measuring changes in women's empowerment and its relationship to intimate partner violence. Development in Practice. 2018;28(5):661–672. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2018.1465025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sita, T., & Dear, G. (2020). Four case studies examining male victims of intimate partner abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 1–22. 10.1080/10926771.2019.1709593.

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Qualitative research in psychology. London, RU: Sage.

- Smith B., & Sparkes A. (2012). Making sense of words and stories in qualitative research: Some strategies for consideration. Tenenbaum G., Eklund R., Kamata A. (Eds.). Measurement in Sport and Exercise Psychology. Champaign, IL: Human kinetics, pp. 119-130.

- Thaggard S, Montayre J. “There was no-one I could turn to because I was ashamed”: Shame in the narratives of women affected by IPV. Women's Studies International Forum. 2019;74:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2019.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torrent, S. (2003). L’homme battu. Un tabou au cœur du tabou. Option Santé Edition. Québec.

- Vanneau, V. (2006). Maris battus: histoire d'une « inversion » des rôles conjugaux. Ethnologie française, 36(4), 697-703. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40990911 ISSN: 0046-2616.

- Vanneste, C. (2017). Violences conjugales: un dilemme pour la justice pénale ? Leçons d’une analyse des enregistrements statistiques effectués dans les parquets belges. Champ Pénal, 14. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/213493

- De Vinck, M. (2004). Les cycles et l'escalade de la violence conjugale. Les tabous. In A. Boas, J. Lambert (eds.). La violence conjugale - Partnergeweld. Bruxelles, Bruylant: Wolters Kluwer.

- Warburton, E., & Raniolo, G. (2020). Domestic abuse during COVID-19: What about the boys? Psychiatry research, 291, Article 113155. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wahed T, Bhuiya A. Battered bodies and shattered minds: Violence against women in Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2007;126(4):341–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K, Bowen E, Brown S, Sleath E. Desistance from intimate partner violence: A conceptual model and framework for practitioners for managing the process of change. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30(15):2726–2750. doi: 10.1177/0886260514553634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K, Bowen E, Brown S, Sleath E. Subjective accounts of the turning points that facilitate desistance from intimate partner violence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2017;61(4):371–396. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15597493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welzer-Lang D. Les hommes battus. Empan. 2009;73(1):81–89. doi: 10.3917/empa.073.0081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods D. Prevalence and patterns of posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and postabused women. Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21(3):309–324. doi: 10.1080/016128400248112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Merritt-gray M. Not going Back. Violence Against Women. 1999;5(2):110–133. doi: 10.1177/1077801299005002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama M, Bybee D. The life history calendar method and multilevel modeling: Application to research on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(2):295–308. doi: 10.1177/1077801211398229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Kohn R. Intimate partner violence and long-term psychosocial functioning in a national sample of American women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(2):262–275. doi: 10.1177/0886260505282564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]