Abstract

One of the basic emotions generated by the COVID-19 pandemic is the fear of contacting this disease. The main aim of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of the Romanian version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S), based on classical test theory and item response theory, namely, graded response model. The FCV-19S was translated into Romanian following a forward-backward translation procedure. The reliability and validity of the instrument were assessed in a sample of 809 adults (34.6% males; Mage = 32.61; SD ±11.25; age range from 18 to 68 years). Results showed that the Romanian FCV-19S had very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .88; McDonald’s omega = .89; composite reliability = .89). The confirmatory factor analysis for one-factor FCV-19S based on the maximum likelihood estimation method with Satorra-Bentler correction for non-normality proved that the model fitted well (CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [.05, .09], SRMR = .01). As for criterion-related validity, the fear of COVID-19 score correlated with depression (r = .25, p < .01), stress (r = .45, p < .01), resilience (r = − .22, p < .01) and happiness (r = −.33, p < .01). The heterotrait-monotrait criteria less than .85 certified the discriminant validity of the FCV-19S-RO. The GRM analysis highlighted robust psychometric properties of the scale and measurement invariance across gender. These findings emphasized validity for the use of Romanian version of FCV-19S and expanding the existing body of research on the fear of COVID-19. Overall, the current research contributes to the literature not only by validating the FCV-19S-RO but also by considering the positive psychology approach in the study of fear of COVID-19, emphasizing a negative relationship among resilience, happiness and fear in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Graded response model, Resilience, Stress, Depression, COVID-19 pandemic

A global pandemic is accompanied by consequences across the world both physically and psychologically as a result of the unexpected and uncontrollable deaths and extraordinarily individual experiences that can impair mental health. One of the basic emotions generated by the COVID-19 pandemic is the fear of contacting this disease, the vaccine for which is still being sought. A plethora of studies has emerged focusing on the deleterious psychological outcomes of the pandemic, with special attention thus being paid to the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health difficulties, more specifically, anxiety (Ahorsu et al. 2020; Mahamid et al. 2020; Perz et al. 2020; Xiang et al. 2020), depression (Pakpour and Griffiths 2020; Lin 2020; Sakib et al. 2020), stress (Pappa et al. 2020; Sahu 2020), suicidal ideation (Griffiths and Mamun 2020; Mamun and Griffiths 2020), medical staff burnout (Greenberg et al. 2020) and ill-being (Lu et al. 2020). Other cognitive aspects related to fear of COVID-19 have been highlighted as well, including impairment of rational thinking (Pakpour and Griffiths 2020) and biased processing of internal cues as a result of inaccurate information or poor/insufficient communication (Garfin et al. 2020) or misinformation in social media (Ho et al. 2020). In addition to the cognitive aspects, studies have examined various psychological correlates such as personality characteristics, namely, intolerance of uncertainty (Mertens et al. 2020; Satici et al. 2020b), nervousness (Sakib et al. 2020) and behaviour change and political beliefs (Winter et al. 2020). In the positive psychology framework, other research has explored the psychological resources used as buffers against the negative impact of COVID-19, such as humour, hope and mindfulness (Saricali et al. 2020), as well the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and life satisfaction (Satici et al. 2020a). Taking into account the aforementioned traumatic consequences on individuals around the world, it is necessary to address fear of COVID-19, not only for research purposes to better understand the phenomenon, its antecedents and its consequences but also for clinical purposes to better prevent it. Thus, in both research and clinical settings, this requires a valid measure of fear of COVID-19. Specialists have recently developed a 7-item unidimensional scale that assesses fear of COVID-19 (Ahorsu et al. 2020). Various studies have confirmed the validity of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) in different cultures (Alyami et al. 2020; Bharatharaj et al. 2020; Doshi et al. 2020; Mahamid et al. 2020; Perz et al. 2020; Satici et al. 2020a; Soraci et al. 2020; Winter et al. 2020). However, just because such an instrument has been validated in many cultures does not mean that it can be translated and used elsewhere; it is necessary to ensure that the concept and measurement of fear of COVID-19 makes sense in a given culture. That is what we have done in Romania by translating and validating the FCV-19S based on classical test theory (CTT) and item response theory (IRT), namely, graded response model (GRM).

Before presenting the results of this validation process, we discuss some particularities of the global health crisis in the context of Romania. As of July 13, 2020, Romania had reported 32,948 cases of COVID-19, with 21,692 recoveries and 1901 deaths; index case was registered on February 26. In the first stage, between February 21 and March 7, the Romanian government decided to impose a 2-week quarantine on people returning from Italy, Spain or China. The week after, a ban on public gatherings, school and bordure closures and a cessation of flights to and from Italy were announced. On March 16, because more than 100 people had been diagnosed with COVID-19, the president declared a 30-day state of emergency in Romania. On March 24, after the first death due to COVID-19, the government imposed a national lockdown. Travel declaration forms were required, and also people had to wear surgical masks in public. Several military ordinances have been issued to reinforce the measures to prevent the spread of coronavirus. In April, over 1000 medical staff in Romania were reported to be infected, and the first death within this professional category, of a 53-year-old paramedic, was recorded. The national lockdown period was extended until May 14, after which a 30-day state of alert began. Restrictions were gradually eased in the following weeks, taking into account that the epidemic had not passed completely. Situation updates on COVID-19 declared that the highest number of people who tested positive for coronavirus in 1 day was recorded on July 21, totalling 994 new cases (STATISTA 2020). This worrying statistic is a potential source of increased fear of COVID-19.

The Current Study

The main aim of this study was to validate the Romanian version of the FCV-19S. The construct validity analysis was based on both CTT (factorial structure, concurrent and discriminant validity) and IRT, namely, GRM. In particular, the reliability of the instrument and the average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the FCV-19S was performed. To gain deeper insights into the psychometric properties of FCV-19S, item parameters (slopes and thresholds) in the observed response patterns were investigated. The boundary characteristics curves (BCCs), the test information function (TIF) and the test characteristics curve (TCC) were analysed. Expected relations of fear of COVID-19 with other variables (i.e. stress, depression, resilience and happiness) were examined. Raising the hypothesis on concurrent validity, presuming a positive relationship among fear of COVID-19, depression and stress, we considered the previous studies that have highlighted the association among these variables (Ahorsu et al. 2020; Bakioglu et al. 2020; Bitan et al. 2020; Cao et al. 2020; Pakpour and Griffiths 2020; Soraci et al. 2020). Another hypothesis on concurrent validity assumed a negative relationship between fear of COVID-19 and resilience based on a positive psychology approach emphasizing the obvious benefit of resilient people in adverse contexts (Smith et al. 2010; Tugade et al. 2004). Resilient people are those who adapt favourably in situations with a high risk of triggering detrimental effects, continuing to maintain their emotional health. According to Fredrickson (2013), high-resilience people have deep emotional self-awareness and counteract the negative effects generated by stressors much faster than people with low resilience. We also presumed a negative relation between fear of COVID-19 and happiness, because it is accepted that people with a high level of happiness have more ability to resist negative experiences or environmental contexts, developing effective coping strategies to manage stressful situations (Smith et al. 2008). Previous research has emphasized that people characterized by a higher level of happiness have emotional well-being and good psychological functioning (Diener and Seligman 2002; Renshaw and Cohen 2014) and are more resistant to mental disorders (Wood and Tarrier 2010). To investigate the discriminant validity of the Romanian version of the FCV-19S, we hypothesised that fear of COVID-19 represents a distinct psychological construct from stress and depression. Taking into account the gender differences in fear of COVID-19 found by Bitan et al. (2020), we assumed that the same pattern would manifest in our sample. To determine whether there are risk groups based on age and level of education, we analysed possible differences taking into account these categories.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment Procedure

Our sample included 809 participants (34.6% males). The age ranged between 18 and 68 years (Mage = 32.61; SD ±11.25). In terms of employment status, as shown in Table 2, more than 80% of the participants had a paid professional activity, most having higher education (around three-quarters). The data were collected online between April 27 and May 10, 2020, during the state of emergency. We shared the online survey via social networking sites, e-mail campaigns, online blogs and WhatsApp in order to recruit volunteer participants. The informed consent that the participants signed allowed them to withdraw at any stage without having to justify their decision. They were guaranteed that their data would remain confidential and anonymous. With regard to attrition, 819 participants were involved to the research at the onset (i.e. attrition rate = 1.22%). The attrition rate is explained by the fact that ten participants who agreed to get involved either gave up after completing the items about demographic variables or did not complete anything. The final sample consisted of 809 participants who completed the questionnaire for the present study.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the Romanian version of the fear of COVID-19 (N = 809)

| Item | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 1 | 5 | 2.59 | 1.15 | 0.19 | 0.71 |

| Item 2 | 1 | 5 | 2.88 | 1.27 | 0.01 | 1.06 |

| Item 3 | 1 | 5 | 1.76 | 1.02 | 1.25 | 0.86 |

| Item 4 | 1 | 5 | 1.67 | 0.95 | 1.42 | 1.50 |

| Item 5 | 1 | 5 | 2.36 | 1.19 | 0.49 | 0.75 |

| Item 6 | 1 | 5 | 1.37 | 0.78 | 2.38 | 5.71 |

| Item 7 | 1 | 5 | 1.48 | 0.87 | 1.90 | 3.07 |

| Total | 7 | 35 | 14.11 | 5.62 | 1.00 | 1.09 |

Ethics

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation. The study adhered to the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration 1975 as revised in 2000. Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of University of Bucharest (Reg.No.CEC: 063/27.04.2020).

Adaptation of the FCV-19S into Romanian

Measures

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Participants were asked about their sociodemographic characteristics: (i) gender, (ii) age, (iii) educational level, (iv) whether they have a paid professional activity and (v) telework during pandemic (part time or full time).

Fear of COVID-19 Scale

(FCV-19S; Ahorsu et al. 2020) This is a 7-item scale (i.e. “I am most afraid of coronavirus-19” and “My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting coronavirus-19”) which globally assesses fear of COVID-19. Items are selected on a 5-item Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Total scores range from 7 to 35. The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale is .82. In this study, we used the original English translation of the FCV-19S (Ahorsu et al. 2020). The translation of the FCV-19S into Romanian was achieved following a forward-backward translation procedure, in accordance with the recommended methodological approach described by Sousa and Rojjanasrirat (2011): (i) translation of the English version of the FCV-19S into Romanian by two independent and well-qualified translators (one of them having knowledge of health terminology); (ii) comparison of the two translated versions of the FCV-19S, checking for possible discrepancies in words, sentences and meanings and generating a synthesis or a preliminary initial translated version; (iii) blind backward translation of the preliminary initial translated version by the other two well-qualified translators; and (iv) comparison between the two backward translations and between both back translations and the original FCV-19S and generating of the second synthesis or translated version. It was noted that no changes were necessary (see the Romanian version of the FCV-19S in Appendix, Table 6).

Table 6.

The English version (Ahorsu et al. 2020) and the Romanian version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale

| Item | The English version | The Romanian version |

|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | I am most afraid of COVID-19 | Îmi este foarte frică de COVID-19 |

| Item 2 | It makes me uncomfortable to think about COVID-19 | Îmi creează disconfort să mă gândesc la COVID-19 |

| Item 3 | My hands become clammy when I think about COVID-19 | Îmi transpiră mâinile când mă gândesc la COVID-19 |

| Item 4 | I am afraid of losing my life because of COVID-19 | Mi-e teamă să nu îmi pierd viața din cauza COVID-19 |

| Item 5 | When watching news and stories about corona viruses-19 on social media, I become nervous or anxious | Când urmăresc știri sau istorisiri despre COVID-19 în social media, devin neliniștit sau anxios/anxioasă |

| Item 6 | I cannot sleep because I am worrying about getting COVID-19 | Nu pot dormi de grija/teama de a lua COVID-19 |

| Item 7 | My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting COVID-19 | Simt că îmi crește tensiunea sau că am palpitații când mă gândesc la COVID-19 |

The Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS; Cohen and Williamson 1988) is a 10-item scale which assesses the global level of perceived stress. It includes both negatively worded questions (i.e. “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed”) and positively worded questions (i.e. “In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way”). Respondents must rate how often they felt a certain way over the past month on a 5-point Likert scale. Each item is scored from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Scores for positively worded items must be reversed to obtain the total score. The total score of the PSS-10 ranges from 10 to 50, and a higher score indicates a higher level of perceived stress. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .81 (95% CI [.79, .82]).

The Short Depression-Happiness Scale (SDHS; Joseph et al. 2004) is a 6-item scale that assesses depression and happiness at the same time. Three items are negative worded (i.e. “I felt cheerless”), and the other three were positively worded (i.e. “I felt happy”), which evaluates the frequency of some mood states in the past week. Each response is scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). The total score of items assessing depression ranges from 3 to 12, and a higher score indicates a higher level of depression. The total score of items assessing happiness ranges from 3 to 12, and a higher score indicates a higher level of happiness. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha of the SHDH was .80 (95% CI [.78, .81]).

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al. 2008) is a 6-item scale which assesses the ability to bounce back or recover from stress. Each item is scored from 1 (disagree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Items include both positively and negatively worded sentences, such as “I usually come through difficult times with little trouble” and “It is hard for me to snap back when something bad happens”. The total score of the BRS ranges from 6 to 30, and a higher score indicates a higher level of resilience. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .85 (95% CI [.82, .86]).

Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed using: STATA 16 (StataCorp 2019) and ADANCO 2.2 (ADANCO 2.2 2020). We first computed the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis of each item of the FCV-19S, univariate normality of all research variables and multivariate normality of the FCV-19S). The cut-off for the substantial departure from univariate normality is an absolute skewness value > 2 and absolute kurtosis value > 7, as recommended by West et al. (1995). Regarding multivariate normality, the expected Mardia’s skewness value is 0 for a multivariate normal distribution, and the expected Mardia’s kurtosis value is 63 (according to Cain et al. 2017). Second, we measured the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha with cut-off criterion > 60 as suggested by Hair et al. (2009). Given the doubts about the relevance of Cronbach’s alpha in assessing the internal consistency of a scale (Revelle and Zinbarg 2009), an alternative and more robust metric was computed, namely, McDonald’s omega. Third, we tested the factorial structure, by means of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), based on the covariance matrix and polychoric correlations, using maximum likelihood estimation with Satorra-Bentler correction for non-normal data (Satorra and Bentler 1994). The measurement model exactly replicated the initial measurement model (Ahorsu et al. 2020) and included one latent variable representing fear of COVID-19. Several goodness-of-fit indices were used to determine the acceptability of the model. In addition to the Chi-square test, which may lead to model rejection even when the model misspecification is relatively minor (Byrne 2001), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMS), the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were used (Acock 2013). According to Hu and Bentler (1999), for CFI, values greater than .90 are acceptable, and greater than .95 are good. The RMSEA and SRMR should preferably be less than or equal to .08. Average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) of the FCV-19S-RO were computed based on λ and ε obtained in CFA. The minimum cut-off level for AVE is .50 (Fornell and Larcker 1981) and for CR is .70 (Chin et al. 2003). Additionally, we measured the information provided by each item of the FCV-19S-RO based on GRM, computing difficulty and discrimination parameters for each item. According to Baker (2001), items with a score of discrimination greater than 1.7 are considered very informative. In addition, differential item functioning (DIF) was used to check the measurement invariance across gender. Fourth, the concurrent validity was verified based on Pearson correlations between fear of COVID-19 and the ordinal variables, that is, stress, depression, resilience and happiness. Fifth, the discriminant validity was checked using heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations method in variance-based structural equation modelling whose latent variables were fear of COVID-19, stress and depression. The cut-off level recommended by Henseler (2020) is HTMT < .85. We also computed one-way ANOVAs to test mean differences for discrete and categorical variables (i.e. age, gender and educational level) in order to identify groups at risk for fear of COVID-19.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 32.61 years (SD ± 11.25). Overall, 34.6% were males. Most of the participants (73.5%) were educated at the tertiary level. The mean, SD, skewness and kurtosis of all items of the Romanian FCV-19S are given in Table 2 and those for other research variables in Table 3. As shown in these tables, overall fear of COVID-19, stress, depression, happiness, and resilience had skewness and kurtosis values of < 2 and < 7, respectively, certifying the univariate normality of the data. Significant Mardia’s skewness [mSkewness = 16.76; χ2(84) = 2265.32, p < .001] and also significant Mardia’s kurtosis [mKurtosis = 90.96; χ2(1) = 1252.51, p < .001] proved the multivariate non-normality of the data.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic variables

| Variables | Category | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 280 | 34.6 | |

| Female | 529 | 65.4 | ||

| Educational level | High-school | 215 | 26.5 | |

| Bachelor | 351 | 43.4 | ||

| Master | 243 | 30.1 | ||

| Paid job | Yes | 651 | 80.5 | |

| No | 158 | 19.5 | ||

| Telework during lockdown | Yes | Part time | 113 | 14.0 |

| Full time | 441 | 54.5 | ||

| No | 255 | 31.5 | ||

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the research variables (perceived stress, depression, happiness, psychological resilience)

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | 10 | 39 | 21.92 | 5.23 | 0.31 | 0.17 |

| Depression | 3 | 12 | 5.15 | 2.03 | 1.08 | 0.92 |

| Happiness | 3 | 12 | 9.44 | 1.96 | − 0.47 | − 0.20 |

| Resilience | 6 | 30 | 21.64 | 4.68 | − 0.28 | − 0.04 |

Internal Consistency

The Cronbach’s alpha obtained, namely, α = .88 (95% CI [.86, .92]), and McDonald’s ω = .89 (95% CI [.86, .89]) indicate very good internal consistency of the Romanian FCV-19S. As shown in Table 4, the corrected item-total correlations were all positive and between .60 and .74. In addition, all the inter-item correlation coefficients were higher than .30 (as recommended Cohen 1992). These values demonstrate that the items surveyed in the Romanian version of the FCV-19S effectively reflect their respective constructs and thereby have a good level of internal consistency.

Table 4.

The corrected item-total correlation (n = 809), the standardized factor loadings in the CFA of the Romanian version of FCV-19S, λ (factor loadings) and ε (standard error of measurement)

| Item | Corrected item-total correlation | Item exclusion or retention | λ | ε |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | .67 | Retained | .72 | .48 |

| Item 2 | .60 | Retained | .60 | .64 |

| Item 3 | .74 | Retained | .81 | .34 |

| Item 4 | .68 | Retained | .77 | .40 |

| Item 5 | .71 | Retained | .72 | .48 |

| Item 6 | .66 | Retained | .72 | .48 |

| Item 7 | .67 | Retained | .73 | .46 |

Factorial Structure—CFA

CFA revealed that all the estimated factor loadings were statistically significant at p < .001. As displayed in Table 4, standardized factor loadings for all items were well above .40, as recommended Pituch and Stevens (2016). They ranged between 0.60 and 0.81. In terms of model fit to the data, a Chi-square test was significant, S-Bχ2 (188) = 730 (p < .001), indicating possible discrepancies or misfit. However, it is accepted in the literature (Pituch and Stevens 2016) that a Chi-square test is impacted by a large sample size. Because CFA is a large sample technique, it is not uncommon to obtain a statistically significant Chi-square test. The Satorra-Bentler scaled test proved a good fit to the data, with CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI, [.05, .09]), SRMR = .01 and CD = .88. These results suggest that the single-factor structure of the FCV-19S-RO fitted well the data. Additionally, the results based on λ and ε obtained in CFA, more precisely AVE (.53) and CR (.89), were both above the minimum cut-off levels recommended. These outcomes prove that the FCV-19S-RO is a valid and reliable measure.

Polytomous IRT Model—Graded Response Model

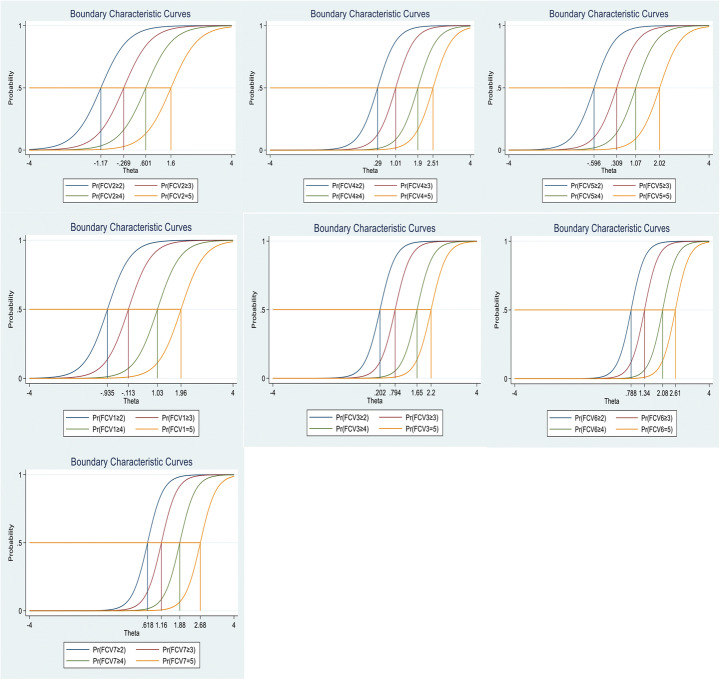

The discrimination and threshold parameters are shown in the Table 5. The results highlight that discrimination (item information) parameters range between 1.88 and 3.59. Thus, all items are highly informative. As emphasized in Table 5, the slopes parameters highlight that all items are above the minimum cut-off level and, thus, all are considered contributory. The item parameters suggest that the fourth threshold (b4) is higher for items 4, 6 and 7 than items 2, 1 and 5 (as shown in Fig. 1). This means that choosing “very often” for items 4, 6 and 7 indicates a higher level of fear of COVID-19 than choosing the same response category for items 2, 1 and 5. In addition, we can observe that item 6 has a slope which is about two times as high as item 2. The difference between these slopes indicates that the response to item 6 is more likely due to the individual’s level of fear of COVID-19 than the response to item 2. The weaker relationship of item 2 to the latent variable suggests that more of the observed variability is due to things other than fear of COVID-19 than is the case in items with higher slopes.

Table 5.

Graded response model parameter estimates for FCV-19 (α the slope parameter estimates and b1, b2, b3 and b4 the threshold parameter estimates)

| Item | α | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 2.22 | − 0.98 | − 0.11 | 1.02 | 1.95 |

| Item 2 | 1.88 | − 1.17 | − 0.26 | 0.60 | 1.59 |

| Item 3 | 3.34 | − 0.20 | 0.79 | 1.65 | 2.20 |

| Item 4 | 2.67 | 0.28 | 1.01 | 1.89 | 2.50 |

| Item 5 | 2.39 | − 0.59 | 0.30 | 1.06 | 2.02 |

| Item 6 | 3.59 | 0.78 | 1.33 | 2.08 | 2.60 |

| Item 7 | 3.31 | 0.61 | 1.15 | 1.87 | 2.68 |

Fig. 1.

Boundary characteristics curves (BCCs) for each item of the Romanian version of the FCV-19S

The calibrated standardized scores (ϴ) obtained for each item and plotted as BBCs graph (see Fig. 1) show that all the items have their apex along the ϴ continuum in the positive half, providing information about fear of COVID-19 when there is an endorsement of the fear characteristic. For example, the item “I cannot sleep because I am worrying about getting COVID-19” is an endorsement of fear by a respondent, as its apex for category 5 (“very often”) is situated in positive ϴ (the fourth threshold being 2.61). Therefore, it is more likely to be endorsed by someone with a high level of fear of COVID-19 than a person endorsing for the same category the item “It makes me uncomfortable to think about COVID-19”, whose apex is also positioned in positive ϴ, but with a lower fourth threshold value (1.60).

The probability range based on each item plotted in BCCs (as shown in Fig. 1) indicates that there is a smaller probability range based on responses 6, 7 and 4 than on response 2. Consequently, it is indicative that items 6, 7 and 4 provide more information than item 2. Choosing someone “very often” for item 6 is suggestive for us that the respondent is most likely between 2.08 and 2.61 on the fear of COVID-19 latent dimension. Selecting that same category for item 2 shows that the respondent is somewhere between 0.60 and 1.60 on the fear of COVID-19 latent variable. In addition, item 2 has the lowest discrimination value (1.88), and thus it provides less information than other items about the respondents who have a high level of fear of COVID-19. Therefore, we can consider items 4 (“I am afraid of losing my life because of COVID-19”), 6 (“I cannot sleep because I am worrying about getting COVID-19”), and 7 (“My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting COVID-19”) more central to the FCV-19S-RO, because they have the highest levels of provided information.

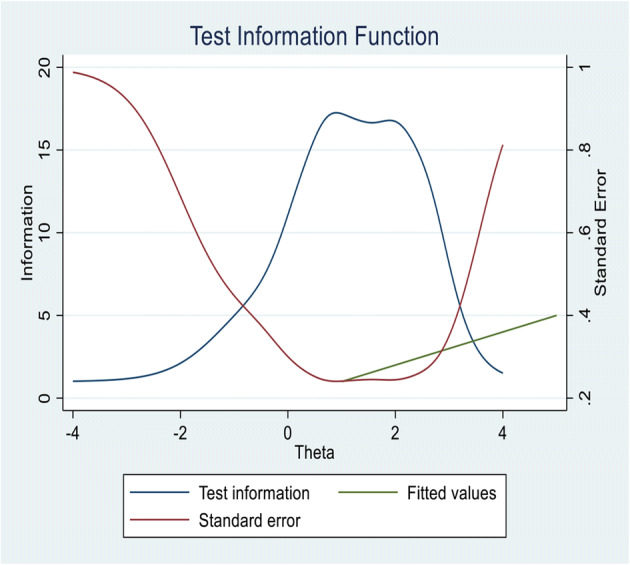

As shown in Fig. 2, for the FCV-19S-RO, the TIF provides relatively uniform information about individuals between ϴ (− 2; 4) with a decline past those points in either direction. In addition, most of the information provided by the scale was above the mean of respondent scores suggesting that the scale is better designed for respondents with higher scores. With regard to the standard errors, we can see that an average score on fear of COVID-19 will have a standard error of 0.3, which is just under a third of a standard deviation. Thus, the TIF proves good evidence of how the Romanian version of FCV-19S is functioning as a whole.

Fig. 2.

Test information function (blue line) and standard errors (red line) to the Romanian version of the FCV-19S

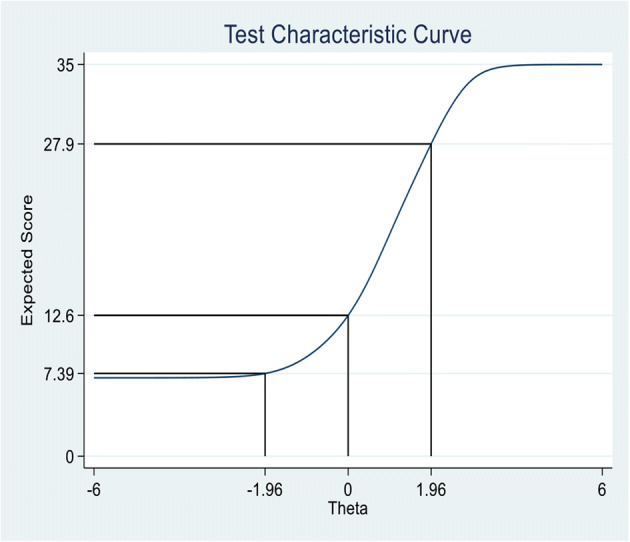

The graph of TCC reveals that the average of the expected scores is around 12.6. Because scores are integers, it would be better to say that the expected scores will be around 13. With regard the 95% confidence bound on the ϴ score, we can see that we expect roughly 95% of the scores to fall between 7 and 28. As shown in Fig. 3, the lines used for various ϴ values, namely, − 1.96; 0; 1.96, map the ϴ scores back to the expected scores.

Fig. 3.

Test characteristics curve for the Romanian version of the FCV-19S

The DIF analysis across gender highlighted that all results [LR χ2(5)] were non-significant and ranged between 7.20 and 10.25, proving that there are no substantial differences between males and females in the response pattern for fear of COVID-19.

Concurrent Validity

The correlations between fear of COVID-19 on the one hand and stress (r(807) = .45, p < .01), depression (r(807) = .25, p < .01), resilience (r(807) = −.33, p < .01) and happiness (r(807) = −.22, p < .01) on the other supported the concurrent validity of the FCV-19S-RO.

Discriminant Validity

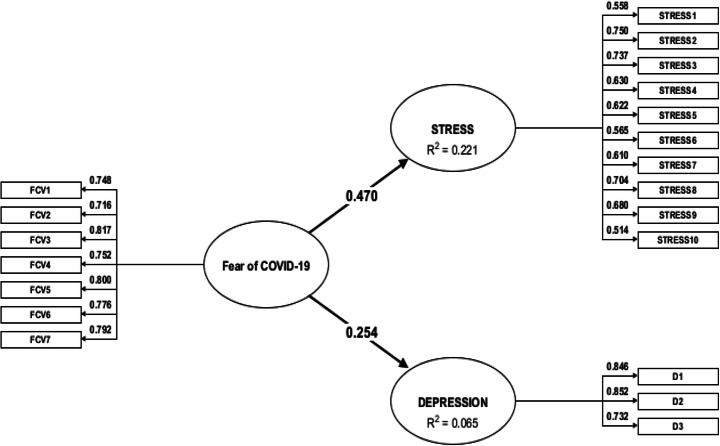

The HTMT criteria obtained in the ratio of correlations analysis in variance-based SEM (see Fig. 4) proved that the FCV-19S-RO assesses psychological phenomena that other two latent variables do not capture. Fear of COVID-19 is a distinct concept from depression (HTMT = .30), respectively stress (HTMT = .51).

Fig. 4.

Variance-based structural equation modelling used in heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations analysis—λ, path loadings, and coefficients of determination

In terms of gender, age and education-level differences, various ANOVAs were performed. In line with our expectations, gender-related differences were found for fear of COVID-19. The results confirmed that females had higher level of fear than males, F(1, 807) = 45.09, p = .001. With regard to age, no differences were found F(4, 804) = 1.08, p = .315. The same pattern was obtained in the case of education level groups F(3, 805) = 1.31, p = .142.

Discussion

Assessing fear of COVID-19 can contribute to the examination of the mental health of general populations during the pandemic. Having a gold and grounded theory tool is helpful not only in screening people with higher levels of fear but also in exploring its predictors and outcomes. In the current study, we tested the psychometric properties of the FCV-19S-RO based both on CTT (i.e. internal consistency, CFA, concurrent and discriminant validity) and on IRT, namely, GRM. The results provided evidence that the FCV-19S-RO had (i) very good internal consistency, (ii) a good level of AVE and CR, (iii) a unidimensional structure (as demonstrated by the CFA), (iv) calibration of all seven items with the latent construct of fear of COVID-19 (as highlighted in the GRM analysis by high information provided by each item), (v) concurrent validity (as demonstrated by the significant positive correlations with depression and stress, respectively negative correlations wit resilience and happiness), (vi) discriminant validity (as demonstrated by the HTMT ratio of correlations) and (vii) measurement invariance of the scale items across gender groups (as demonstrated by the GRM/DIF analysis). Thus, the results of the present study provide empirical support for the strong psychometric qualities of the FCV-19S-RO. More specifically, our findings are in the same line with those obtained in the original study, namely, the validation in Farsi/Persian (Ahorsu et al. 2020), or other validation studies in various cultures (Alyami et al. 2020; Perz et al. 2020; Satici et al. 2020a; Soraci et al. 2020) taking into account (i) the great level of internal consistency, proving so the accuracy of the scale; (ii) the replication of the one-single factor structure, items having high factorial loadings; and (iii) the very good fit indices between data and the proposed model, as demonstrated in the CFA analysis. In the same vein, the results of the present study, as well of some previous research based on IRT models (Bharatharaj et al. 2020; Sakib et al. 2020), highlight that the data fit the GRM model very well. The high information provided by all items was certified, and the obtained slopes proved adequate discrimination of all items, covering a wide range of the latent construct, that is, fear of COVID-19. In addition, the DIF analysis emphasizes that the FCV-19S-RO could be used in the general population irrespective of gender. As we expected, our results provide evidence for the association between fear of COVID-19 on the one hand and resilience and happiness on the other. To our knowledge, only two previous studies have been conducted on this topic from the perspective of positive psychology (i.e. the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mindfulness, hopelessness and humour (Saricali et al. (2020)); the association between fear of COVID-19 and life satisfaction (Satici et al. (2020a))). In addition, our findings replicate the positive associations among fear of COVID-19, depression scores and stress highlighted in Iranian culture (Ahorsu et al. 2020), Chinese culture (Chang et al. 2020) and Italian culture (Soraci et al. 2020). All three studies, like the present one, were cross-sectional, and thus it was not possible to explain the direction of this association. Only experimental and/or longitudinal studies would clarify and certify the direction of this complex relationship.

As statistics show that the rate of illness is lower among young people than in adults and the elderly (World Health Organization n.d.; WHO), we would have expected to find age differences in terms of fear of COVID-19. However, our results showed that people face this fear regardless of age. According to Pakpour and Griffiths (2020), when there is a global pandemic, people at all ages feel threatened and answer questions in a similar way. Our findings are in line with those obtained by Mahamid et al. (2020) who emphasized gender differences, with females experiencing greater fear than males. In the present study, females reported higher levels of fear of COVID-19 than males. It is generally accepted that females face higher levels of fear of contamination than males (Olatunji et al. 2005). Because the FCV-19S includes self-report items, we should consider not only the desirability bias but also the fact that the subjective perception of fear level could have been influenced by the widely accepted stereotypes that men are strong and therefore must not express helplessness, fear or dread. There is a greater social acceptability of expressing and sharing basic emotions such as fear among women and anger among men (Stănculescu 2009, 2013). With regard to the relation between fear of COVID-19 and level of education, although previous research (Mahamid et al. 2020) has shown that those with compulsory studies face a significantly higher level of fear than the highly educated, in the present study, no such differences were found. A possible explanation is that because the data were gathered online, most participants have a high level of education (bachelor’s and master’s degrees). Therefore, there were no dissimilarities depending on this sociodemographic variable.

This paper provides empirical support that extends the growing research body on fear of COVID-19. This is the first such study conducted in Romania and the second in the Eastern European region. The first one was developed on a Russian sample (Reznik et al. 2020). Romania it is the only Latin country in this region, all the other cultures being Slavic. Summing up, this research highlighted that the FCV-19S-RO has robust psychometric properties and can be used by health professionals in assessing fear of COVID-19 and preventing maladaptive behaviours generated by it. The validation of the Romanian version opens up to carry out future research on antecedents and outcomes of fear of COVID-19. Overall, our research contributes to the literature not only by validating the FCV-19S-RO but also by considering the positive psychology approach in the study of fear of COVID-19, emphasizing a negative relationship among resilience, happiness and fear in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study has several limitations, even though it provided strong evidence for the validity of the FCV-19S-RO. First, although the present study was carried out among a relatively large sample, it is not representative of the whole Romanian population. Additionally, the mean level of fear of COVID-19 in our sample was quite low, which suggests that the number of people with a high level of fear is limited. Second, fear is known to be a subjective perception associated with shortcomings when trying to evaluate it objectively, taking into consideration that answers could be distorted by the social desirability bias. Consequently, further verification—using objective measures of fear, for example, biomarkers such as heart rate or hair cortisol measured in experimental situations when participants are focusing on issues generated by the global pandemic—are needed. It may be fruitful to develop an inquiry to better understand the nature of and how fear is experienced, exploring real experiences through qualitative research methods such as phenomenology. Third, the current study did not provide evidence for predictive validity with regard to the specific consequences of fear of COVID-19 (in particular, suicidal ideations, anxiety and depression). Fourth, the predominance of highly educated participants in the sample of the present research weakens the generalizability of the findings. However, the evidence of the reliability and validity of the FCV-19S-RO represents a starting point for Romanian psychologists to explore this research topic, which is currently of great interest to many specialists from various cultures in order to prevent deleterious outcomes. This tool is also suitable to be used for large-scale epidemiological studies and to detect the presence and magnitude of fear of COVID-19 in Romania, in both public and private settings.

Appendix

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University’s Research Ethics Committee (Reg.No.CEC: 063/27.04.2020) and with the Helsinki declaration.1975 as revised in 2000.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acock, A. C. (2013). Discovering structural equation modeling using Stata. StataCorp LP.

- ADANCO 2.2 (2020). Composite modeling. Advances analysis of composite. Composite Modeling GmbH & Co.

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C.-Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alyami, M., Henning, M., Krägeloh, C. U., & Alyami, H. (2020). Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00316-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baker, F. B. (2001). The basics of item response theory (second edition). ERIC. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED458219. Accessed 24 Jul 2020.

- Bakioglu, F., Korkmaz, O., & Ercan, H. (2020). Fear of COVID-19 and positivity: mediating Rrle of intolerance of uncertainty, depression, anxiety, and stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bharatharaj, J., Alyami, M., Henning, M. A., Alyami, H., & Krägeloh, C. U. (2020). Tamil version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-40914/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bitan DT, Grossman-Giron A, Bloch Y, Mayer Y, Shiffman N, Mendlovic S. Fear of COVID-19 scale: psychometric characteristics, reliability and validity in the Israeli population. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113100. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cain MK, Zhang Z, Yuan KH. Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence and estimation. Behavior Research Methods. 2017;49:1716–1735. doi: 10.3758/s13428-016-0814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K. C., Hou, W. L., Pakpour, A. H., Lin, C. Y., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Psychometric testing of three COVID-19-related scales among people with mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–13. 10.1007/s11469-020-00361-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chin W, Marcolin B, Newsted P. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research. 2003;14(2):189–217. doi: 10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992;1(3):98–101. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on applied social psychology (pp. 31–67). Sage publications.

- Diener E, Seligman MEP. Very happy people. Psychological Science. 2002;13:81. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi, D., Karunakar, P., Sukhabogi, J. R., Prasanna, J. S., & Mahajan, S. V. (2020). Assessing coronavirus fear in Indian population using the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00332-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.). Advances in experimental social psychology, 47, (pp. 3–53). Academic Press.

- Garfin R, Cohen Silver R, Holman A. The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychology. 2020;39(5):355–357. doi: 10.1037/hea0000875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, N., Docherty, M., Granapragasam, S., & Wessely, S. (2020). Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. British Medical Journal, 368. 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Griffiths MD, Mamun MA. COVID-19 suicidal behavior among couples and suicide pacts: case study evidence from press reports. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113105. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice-Hall Inc..

- Henseler, J. (2020). Composite-based structural equation modeling: analyzing latent and emergent variables. Guilford Press.

- Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Annals Academy of Medicine Singapore. 2020;49:1–3. doi: 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2019252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Linley A, Harwood J, Lewis CA, McCollam P. Rapid assessment of well-being: the short depression-happiness scale (SDHS) Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2004;77:463–478. doi: 10.1348/1476083042555406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. Social reaction toward the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Social Health and Behavior. 2020;3(1):1. doi: 10.4103/SHB.SHB_11_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamid, F. A., Bdier, D., & Berte, D. Z. (2020). Psychometric properties of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCOVID-19S) in a Palestinian context. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–14.

- Mamun MA, Griffiths MD. First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;51:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, G., Gerritsen, L., Salemink, E., & Engelhard, I. (2020). Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): predictors in an online study conducted in march 2020. PsyArXiv Preprints. 10.31234/osf.io/2p57j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Olatunji BO, Sawchuk CN, Arrindell WA, Lohr JM. Disgust sensitivity as a mediator of the sex differences in contamination fears. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38(3):713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pakpour, A., & Griffiths, M. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 and its role in preventive behaviors. Journal of Concurrent Disorders.

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perz, C. A., Lang, B. A., & Harrington, R. (2020). Validation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in a US college sample. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00356-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2016). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS (6th ed.). Routledge Taylor & Frances Group.

- Renshaw TL, Cohen AS. Life satisfaction as a distinguishing indicator of college student functioning: Further validation of the two-continuum model of mental health. Social Indicators Research. 2014;117:319–334. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0342-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W, Zinbarg R. Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the GLB : comments on Sijtma. Psychometrika. 2009;74(1):145–154. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9102-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reznik, A., Gritsenko, V., Konstantinov, V., Khamenka, N., & Isralowitz, R. (2020). COVID-19 fear in Eastern Europe: validation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7541. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakib, N., Mamun, M. A., Bhuiyan, A. I., Hossain, S., Al Mamun, F., Hosen, I., Abdullah, A. H., Sarker, A., Mohiuddin, M. S., Rayhan, I., Hossain, M., Sikder, T., Gozal, D., Muhit, M. A., Islam, S. M. S., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). Psychometric validation of the Bangla Fear of COVID-19 Scale: confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00289-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Saricali, M., Satici, S. A., Satici, B., Gocet-Tekin, E., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Fear of COVID-19, mindfulness, humor, and hopelessness: a multiple mediation analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Satici, B., Gocet-Tekin, E., Deniz, M. E., & Satici, S. A. (2020a). Adaptation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–9. 10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Satici, B., Saricali, M., Satici, S. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020b). Intolerance of uncertainty and mental wellbeing: Serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11469-020-00305-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C. C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent variables analysis: applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Smith BV, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Tooley EM, Christofer P, Kay VS. Resilience as the ability to bounce back from stress: a neglected personal resource? The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2010;5(3):166–176. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2010.482186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soraci, P., Ferrari, A., Abbiati, F. A., Del Fante, E., De Pace, R., Urso, A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Validation and psychometric evaluation of the Italian version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00277-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2011;17:268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stănculescu E. Stereotipurile de gen din perspectiva cogniției sociale. Revista de Psihologie. 2009;55(3–4):213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stănculescu, E. (2013). Fascinația stereotipurilor în psihologia socială. [Fascination of the stereotypes in social psychology]. Editura Academiei Române.

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata®. Statistics. Data analysis. Statistical software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC.

- STATISTA. (2020). Statista. Number of new coronavirus (COVID-19) cases in Romania as of July 21, 2020, by day of report. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1104612/romania-confirmed-covid-19-cases/. Accessed 24 Jul 2020.

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Feldman-Barrett L. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(6):1161–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: problems and remedies. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T., Riordan, B. C., Pakpour, A. H., Griffiths, M. D., Mason, A., Poulgrain, J. W., & Scarf, D. (2020). Evaluation of the English version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale and its relationship with behavior change and political beliefs. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00342-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wood AM, Tarrier N. Positive clinical psychology: a new vision and strategy for integrated research and practice. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:819–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (n.d.). Novel Coronavirus situation. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/685d0ace521648f8a5beeeee1b9125cd. Accessed 24 Jul 2020.

- Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, Ng CH. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):228–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]