Abstract

Traditional knowledge on the use of medicinal plants is in danger of extinction because of different changes taking place all over the world including Ethiopia, and thus, there is a need for its immediate documentation for the purpose of conservation, sustainable utilization, and development. Thus, an ethnobotanical study was conducted in Ambo District, Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia, to document and analyze local knowledge on medicinal plants used for the treatment of animal diseases. Data were collected between November 2017 and April 2018 mainly through semi-interviews conducted with purposively selected informants. Data collected mainly included demographic information of respondents, local names of medicinal plants, plant parts used, preparation methods, mode of applications, diseases treated, and habit and habitat of the reported plants. Based on data obtained through interviews, informant consensus factor (ICF) values were computed. A total of 55 medicinal plants used to manage livestock ailment were reported by informants in the Ambo District. Herbs were commonly used in the preparation of remedies. Leaf was the most frequently utilized plant part accounting for 49.1% of the total reported medicinal plants. The majority (69.0%) of the medicinal plants used in the study district were uncultivated ones mainly harvested from edges of forests and bushlands, roadsides, riverbanks, and grasslands. High ICF values were obtained for ophthalmological (0.82), dermatological (0.79), febrile (0.77), and gastrointestinal ailments (0.77). The current study shows that there is still rich traditional knowledge on the use of plants to control various animal diseases in the study district. However, such a claim needs to be scientifically verified with priority given to medicinal plants used in the treatment of ailment categories with high ICF values as such plants are considered to be good candidates for further pharmacological evaluation.

1. Introduction

In Ethiopia, traditional medicine, in general, and medicinal plants, in particular, are still playing a significant role in solving livestock health problems [1]. Ethnoveterinary systems of treatment are still widely used even in areas where modern veterinary services have been introduced many years ago [2]. However, despite the significant role that has been played by medicinal plants in treating livestock ailments in both settled and pastoralist areas in Ethiopia, very limited attempts have been done to explore, document, evaluate and develop, and promote them for their wider uses in the country [3]. Survey to document and analyze the traditional use of medicinal plants is an urgent matter as both plant materials and the associated traditional knowledge are currently being lost at an alarming rate due to various factors mainly including environmental degradation, deforestation, and acculturation [4–6].

There are several ethnoveterinary surveys carried out in Oromia Region of Ethiopia to which also the Ambo District belongs [7–13]. However, a literature survey shows that there was no proper ethnoveterinary study so far conducted in Ambo District to document the use of medicinal plants in managing livestock ailments. Some personal communications indicate the wide practice of using medicinal plants to control different types of animal health problems in the study area. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to document and analyze medicinal plants used to treat livestock diseases in Ambo District of the Oromia Region of Ethiopia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Area

Ambo District administratively belongs to West Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia. Ambo town is an administrative centre for both Ambo District and West Shoa Zone. The town is located at a distance of 114 km west of Addis Ababa within latitudes of 8°59′ and 8.983° N and longitudes of 37°51′ and 37.85° E and has an elevation of 2101 meters above sea level [14]. Ambo town has an annual rainfall of 1007.3 mm and mean minimum, mean maximum, and mean average monthly temperatures of 9.96°C, 19.82°C, and 14.89°C, respectively [15]. According to Tamiru et al. [14], the agroecology of Ambo District consists of highland (23%), midland (60%), and lowland (17%). The District is divided into 34 administrative kebeles; kebele is the smallest unit of administration in Ethiopia.

The livelihood of people in the district is largely dependent on agriculture mainly involving crop production and animal rearing [16]. The district has a livestock population of 145371 cattle, 50152 sheep, 27026 goats, 105794 chickens, 9088 horses, 2914 donkeys, and 256 mules [14]. Liver fluke, pasteurellosis, blackleg, epizootic lymphangitis, African horse sickness, trypanosomiasis, ascariasis, leech worm infestation, gastrointestinal parasites infection, lumpy skin disease, anthrax, and foot and mouth disease are the commonly occurring diseases in the study district, of which anthrax, blackleg, and foot and mouth disease are considered the most serious ones [17]. There are 13 veterinary clinics in the study district and a total of 21 veterinary professionals, of which four are DVM holders, three are BVSc holders and 14 are animal health attendants (Ambo District Agriculture Office, unpublished data, 2018).

2.2. Informants Sampling and Data Collection

A total of 55 knowledgeable informants with ages ranging from 35 to 71 years were purposively selected from the study district with the support of the Ambo District Administration Office and respected local elders. Of these, 31 were males and 14 were females. Ethnoveterinary data were collected from November 2017 to April 2018 through individual semistructured interviews that were held with the selected informants. In the interviews conducted in the Oromo language, the widely spoken language in the study area, data on sociodemography of the informant, local names of medicinal plants used in ethnoveterinary practices, parts used, preparation methods, mode of applications, and diseases treated were collected. Data related to habitats of threats to medicinal plants were also gathered during interviews. Prior informed consent was obtained from all informants who participated in the study. Voucher specimens of medicinal plants reported during interviews were collected, properly pressed, dried, and identified by their scientific names by a botanist at Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology (ALIPB), Addis Ababa University, and were deposited at the miniherbarium of the Medicinal Plants Unit at ALIPB.

2.3. Data Analysis

Ethnobotanical data on the local use of medicinal plants were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, analyzed using SPSS version 20 software, and summarized using appropriate descriptive statistical methods. Informant consensus factor (ICF) values were also calculated to determine the level of agreement of informants on the reported medicinal plants for the treatment of a given major ailment category using the formula ICF =(nur − nt)/(nur − 1), where nur = number of informant citations for a particular ailment category and nt = number of medicinal plants used for the same ailment category with ICF values ranging between 0.00 and 1.00 [18]. ICF helps in the identification of medicinal plants with relatively higher informants' agreement in choosing them in the treatment of a given ailment category [19]. Grouping the specific ailments into major ailment categories was made with the assistance of a veterinarian at ALIPB, Addis Ababa University, following the approach of Heinrich et al. [18]. ICF values were calculated for major disease categories against which at least five informant use reports were recorded following the approach of Lautenschläger et al. [20].

3. Results

3.1. Medicinal Plants Used and Ailments Managed

The current study documented 55 medicinal plant species that were used in Ambo District to manage several livestock ailments (Table 1). The plants were distributed across 36 families and 53 genera. Of the total medicinal plants reported, relatively higher numbers of medicinal plants belonged to the families Euphorbiaceae and Lamiaceae, each contributing five species. The families Fabaceae and Solanaceae contributed four medicinal plants each, and the families Acanthaceae, Asteraceae, Malvaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Rubiaceae contributed two medicinal plants each. The rest of the families contributed one medicinal plant each. Herbs were the most commonly used ones in the preparation of remedies in the study district accounting for 32 species (58.2%), followed by shrubs (17 species; 30.9%) and trees (6 species; 10.9%). The highest number of medicinal plants (29 species) was used to manage gastrointestinal complaints including bloat, colic, endoparasites infections, and diarrhea which largely affect cattle, sheep, and goats. A good number of medicinal plants were also used to treat febrile illness (9 species) and eye infection (5 species).

Table 1.

Lists of medicinal plants used for treatments of livestock diseases in Ambo District.

| Scientific name | Family | Local name | Habit | Part used | Local disease name | English disease name | Mode of preparation | Dose and treatment duration | Animal treated | Administration route | Voucher number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia abyssinica Benth. | Fabaceae | Laaftoo | Tree | Leaf | Bofatu arge (afuura bofaa) | Snakebite | Chewing | One mouthful of juice per day until healing | Bovine | Topical | MB-18 |

| Acanthus pubescens (Oliv.) Engl. | Acanthaceae | Kosorruu | Shrub | Root | Dhibee ijaa | Eye infection | Crushing | Few drops per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Ophthalmic | MB-20 |

| Ajuga integrifolia Buch.-Ham. | Lamiaceae | Armaguusa | Herb | Leaf | Michii | Febrile illness | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-30 |

| Allium sativum L. | Alliaceae | Qullubbii adii | Herb | Leaf (bulb) | Dhukkuba garaa keessaa, ciniinnaa, bokoka | Abdominal pain, colic, bloat | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Aloe pubescens Reynolds | Aloaceae | Argiisa | Shrub | Leaf sap | Madaa waanjoo | Wound | Cutting and collecting the jelly | Half coffee cup a day until healing | Bovine, equine | Topical | MB-40 |

| Amaranthus caudatus L. | Amaranthaceae | Ayyaansoo | Herb | Leaf | Albaatii | Diarrhea | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine caprine | Oral | — |

| Anethum graveolens L. | Apiaceae | Insilaalee | Herb | Leaf | Bokoka | Bloat | Crushing and adding water | One can for one day | Bovine | Oral | MB-53 |

| Bidens pilosa L. | Asteraceae | Dhama'ee | Herb | Root | Dhibeeijaa | Eye infection | Crushing | Few drops per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Ophthalmic | MB-49 |

| Brassica carinata A.Braun | Brassicaceae | Raafuu | Herb | Leaf | Bokoka | Bloat | Macerating in water | One can for one day | Bovine | Oral | — |

| Brassica nigra (L.) K.Koch | Brassicaceae | Senaafica | Herb | Seed | Rakkoo dakamuu nyaataa, ciniinnaa, bokoka | Indigestion, colic, bloat | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Brucea antidysenterica J.F.Mill. | Simaroubaceae | Qomanyoo | Shrub | Root | Dhibee sirna hargansuu | Breathing problem | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-10 |

| Buddleja polystachya Fresen. | Loganiaceae | Anfaara | Shrub | Leaf | Bokoka | Bloat | Crushing and adding water | One can for one day | Bovine | Oral | MB-48 |

| Calpurnia aurea (Aiton) Benth. | Fabaceae | Ceekaa | Shrub | Leaf | Injiraan balleesuuf | Pediculosis | Soaking in water | Few cans per day until parasite load diminishes | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Topical | MB-39 |

| Capsicum annuum L. | Solanaceae | Barbaree | Herb | Fruit | Ciniinnaa | Colic | Grinding and adding water | One glass or can for one day | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Carissa spinarum L. | Apocynaceae | Agamsa | Shrub | Root | Dhibee sirna hargansuu | Breathing problem | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-38 |

| Chloris gayana Kunth | Poaceae | Coqorsa | Herb | Whole plant | Afuurabofaa | Snakebite | Chewing | One mouthful of juice for one day | Bovine | Topical | MB-19 |

| Clematis hirsute Guill. & Perr. | Ranunculaceae | Hiddaadii | Shrub (climber) | Whole plant | Dhibee ijaa | Eye infection | Grinding | Some powder per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Ophthalmic | MB-16 |

| Coffea arabica L. | Rubiaceae | Buna | Shrub | Seed | Madaa | Wound | Roasting and grinding | Some powder per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Topical | — |

| Croton macrostachyus Hochst. ex Delile | Euphorbiaceae | Bakkanniisa | Tree | Leaf | Biichee, o'ichoo | Lymphangitis, foot rot | Crushing and adding water crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day for seven days one glass or can per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral and topical | MB-01 |

| Cucumis ficifolius A.Rich. | Cucurbitaceae | Hiddiihooloo | Herb (trailing) | Fruit | Rammoo garaa | Endoparasites infection | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-15 |

| Datura stramonium L. | Solanaceae | Asaangira | Herb | Leaf | Qaafirafardaa | Systemic illness | Crushing and macerating in water | One can per day for two days | Equine | Oral | MB-02 |

| Dodonaea angustifolia L.f. | Sapindaceae | Ittacha | Shrub | Leaf | Caba | Fracture | Rubbing between hands | Tying until healing | Bovine | Tied on the fractured site | MB-47 |

| Ensete ventricosum (Welw.) Cheesman | Musaceae | Warqee | Herb | Whole plant | Dhibeeijaa | Eye infection | Chewing | One mouthful juice per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Ophthalmic | MB-37 |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Myrtaceae | Bargamooadii | Tree | Leaf | Michii | Febrile illness | Boiling in water | Some steam per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Fumigation | MB-23 |

| Euphorbia lathyris L. | Euphorbiaceae | Adaamii | Herb | Stem bark | Furroo | Strangle | Burning | Some smoke per day until healing | Equine | Fumigation | MB-17 |

| Gardenia ternifolia Schumach. & Thonn. | Rubiaceae | Gambeela | Tree | Leaf | Dhibeeijaa | Eye infection | Chewing | One mouthful juice per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Ophthalmic | — |

| Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce ex Steud.) J.F.Gmel. | Rosaceae | Heexoo | Tree | Fruit | Raammoo garaa | Endoparasites infection | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-26 |

| Ipomoea cairica (L.) Sweet | Convolvulaceae | Hiddaqarac | Herb | Root | Albaatii | Diarrhea | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-22 |

| Juniperus procera Hochst. Ex Endl. | Cupressaceae | Gaattiraa | Tree | Leaf | Maxxantoota alaa | Ectoparasites infestation | Soaking in water | Few cans per day until parasite load diminishes | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Topical | MB-12 |

| Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. Ex Nees) T. Anderson | Acanthaceae | Sansallii | Shrub | Leaf | Dhukkuba saree ittisuuf | Rabies | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day for three days | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-14 |

| Kalanchoe sp. | Crassulaceae | Bosoqqee | Herb | Root | Abba sangaa, Kintaarotii | Anthrax | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day for seven days | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-52 |

| Lens culinaris Medik. | Fabaceae | Missira | Herb | Seed | Dhibee sharariitii | Spider poisoning | Chewing | One mouthful of paste for one day | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Topical | — |

| Leonotis ocymifolia (Burm.f.) Iwarsson | Lamiaceae | Raaskimmirii | Herb | Leaf | Michii | Febrile illness | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-29 |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Brassicaceae | Feecoo | Herb | Seed | Bokoka, ciniinnaa, maxxantoota keessaa | Bloat, colic, endoparasites infection | Grinding and adding water grinding and adding water | One glass or can for one day one glass or can for one day | Bovine, ovine, caprine bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Linum usitatissimum L. | Linaceae | Talbaa | Herb | Seed | Dhoqqeen garaatti goguu, dil'uuture | Constipation, retained placenta | Crushing and adding water Crushing and adding water | One glass or can until recovery One glass or can for one day | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Malva verticillata L. | Malvaceae | Xoqonuu/liitii | Herb | Root | dil'uuture | Retained placenta | Crushing and adding water | One can for one day | Bovine | Oral | MB-55 |

| Nicotiana tabacum L. | Solanaceae | Tamboo | Herb | Leaf | Dhulaandhula, dhukkubagaraa, ciniinnaa, bokoka | Leech infestation, abdominal pain, colic, bloat | Crushing and adding water crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until parasite detaches one glass or can for one day | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Nasal and oral | MB-04 |

| Nigella sativa L. | Ranunculaceae | Abasuudagurracha | Herb | Seed | Ciniinnaa | Colic | Grinding and adding water | One glass or can until symptom ceases | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. Ex Benth. | Lamiaceae | Daamaakasee | Shrub | Leaf | Michii | Febrile illness | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-28 |

| Ocimum urticifolium Roth | Lamiaceae | Ancabbii | Shrub | Leaf | Michii | Febrile illness | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-32 |

| Phytolacca dodecandra L'Hér. | Phytolaccaceae | Andoodee | Shrub | Root | Dhibee saree, dhulaandhula | Rabies, leech infestation | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral and nasal | MB-03 |

| Rhamnus prinoides L'Hér. | Rhamnaceae | Geeshoo | Shrub | Leaf | Dhibee saree | Rabies | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-05 |

| Ricinus communis L. | Euphorbiaceae | Qobboo | Herb | Leaf | Qabbana | Foot and mouth disease | Crushing and adding water | One can per day until healing | Bovine | Oral | MB-41 |

| Rumex nepalensis Spreng. | Polygonaceae | Tultii | Herb | Root | Ciniinnaa | Colic | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can for one day | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-25 |

| Ruta chalepensis L. | Rutaceae | Ciraakkota | Shrub | Leaf | Michii, dhulaandhula | Febrile illness, leech infestation | Crashing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral and nasal | MB-44 |

| Salvia nilotica Juss. ex Jacq. | Lamiaceae | Bokkolluu | Herb | Leaf | Michii | Febrile illness | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Scadoxus multiflorus (Martyn) Raf. | Amaryllidaceae | Caraanaa | Herb | Root | Albaatii | Diarrhea | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until healing | Bovine | Oral | MB-54 |

| Sida ternate L. f. | Malvaceae | Hiddalaaluu | Herb (trailing) | Root | Albaatii | Diarrhea | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Solanecio gigas (Vatke) C. Jeffrey | Euphorbiaceae | Bosoqa | Herb | Leaf | Michii | Febrile illness | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-31 |

| Solanum giganteum Jacq. | Solanaceae | Hiddiiongorcaa | Shrub | Fruit | Qufaa | Cough | Roasting | Handful of fruits per day until recovery | Horse | Oral | MB-45 |

| Stephania abyssinica (Quart.-Dill. & A. Rich.) Walp. | Menispermaceae | Kalaalaa | Herb | Leaf | Dhibee saree, madaa | Rabies, wound | Crushing and adding water Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day for three days One glass or can per day until healing | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral and topical | MB-13 |

| Tragia plukenetii Radcl.-Sm. | Euphorbiaceae | Doobbii | Herb | Root | dil'uuture, dhulaandhula | Retained placenta, leech infestation | Crushing and adding water Crushing and adding water | One can for one day One can per day until parasite is removed | Bovine | Oral and nasal | MB-11 |

| Trigonella foenum-graecum L. | Fabaceae | Abishii | Herb | Seed | Rammoogaraa | Endoparasites infection | Grinding and soaking powder in water | One glass or can per day until body condition improved | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

| Vernonia amygdalina Delile | Asteraceae | Eebicha | Shrub | Leaf | Michii, Bokoka, Maxxantoota keessaa | Febrile illness, bloat, endoparasites infection | Crushing and adding water | One glass or can per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | MB-06 |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Zingiberaceae | Zingibila | Herb | Stem (tuber) | Dhibee garaa keessaa, bokoka, | Abdominal pain, bloat | Crushing and adding water | One glass or pan per day until recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | Oral | — |

3.2. Part Used, Methods of Preparation, and Route of Administration

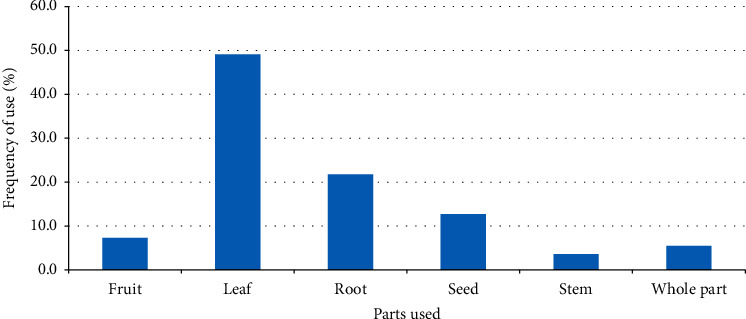

Leaf was the most commonly used plant part in the preparation of remedies accounting for 49.1% of the total reported medicinal plants, followed by those used for their root (21.8%) and seed (12.7%) parts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of plant parts used in the preparation of remedies in Ambo District.

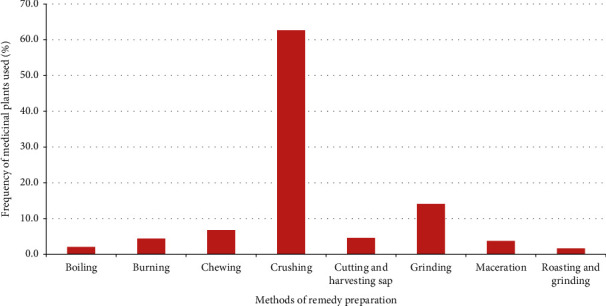

The result shows that most (62.7%) remedies in the study district were prepared by crushing (Figure 2). There was very little practice of storing plant materials for future use in the study district; plant parts were mostly harvested for their immediate uses. As a result, the majority (72.1%) of remedies were prepared from fresh plant materials. Only a few were prepared from dry (22.9%) or dry or fresh (5.0%) materials. Most (85.3%) remedies were processed with the addition of water, while few (14.7%) were prepared without the use of any diluent. The majority (58.2%) of medicinal plant preparations were revealed to be administered orally, and some were administered dermally (19.5%), taken nasally (18.8%), or applied through the eyes (3.5%).

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of the different remedy preparation methods in Ambo District.

3.3. Informant Consensus Factor

ICF values were calculated for major disease categories against which at least five informant use reports were recorded. Accordingly, ophthalmological (0.82), dermatological (0.79), febrile (0.77), and gastrointestinal (0.77) ailments were found to be the major disease categories that scored high ICF values in the study district (Table 2).

Table 2.

Informant consensus factor calculated for major disease categories in Ambo District.

| Category of the disease | Numbers of plant species | Number of informant citations | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ophthalmological | 4 | 18 | 0.82 |

| Dermatological | 10 | 43 | 0.79 |

| Febrile | 10 | 40 | 0.77 |

| Gastrointestinal | 19 | 78 | 0.77 |

| Snake and spider poisoning | 4 | 12 | 0.73 |

| Nervous system | 6 | 18 | 0.71 |

| Respiratory system | 5 | 12 | 0.64 |

| Reproductive system | 3 | 5 | 0.50 |

| Others/unclassified | 5 | 6 | 0.20 |

3.4. Habitat

The majority (69.0%) of the claimed medicinal plants in the study district were found to be uncultivated ones mainly harvested from edges of forests and bushlands, roadsides, riverbanks, and grasslands. Few of the uncultivated ones were weeds growing in cultivated fields and home gardens. Some (31.0%) of the reported medicinal plants were cultivated in home gardens but primarily for other purposes. Only Ocimum lamiifolium, Ocimum urticifolium, and Lepidium sativum were cultivated in the home garden primarily for their medicinal uses.

3.5. Comparison of Knowledge of Medicinal Plants between Different Social Groups

Analysis of data collected revealed a significant difference (p < 0.05) in medicinal plant knowledge between the older (≥46 years of age) and the younger (<46 years of age) people. The mean number of medicinal plants reported by the older people was 5.2 while that reported by the younger people was 3.0. The study further showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) between males and females in the mean number of medicinal plants reported; 4.5 and 3.2 were the mean numbers of medicinal plants reported by males and females, respectively. However, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05), in the mean number of medicinal plants reported, between illiterate (those who cannot read and write) (4.3) and literate (those who can read and write) (4.1) people.

4. Discussion

4.1. Medicinal Plants Used and Ailments Managed

The number of medicinal plants (55 species) documented from Ambo District that was used to manage several livestock ailments is comparable to a figure reported by a study conducted in Midakegn District of West Shoa Zone, to which also Ambo District belongs, which revealed the use of 60 medicinal plants to treat different livestock ailments [12]. On the other hand, the number of medicinal plants reported by the current study is much higher as compared to figures reported by studies conducted in different districts of three neighboring zones of the Oromia Region, namely, Horro Guduru, Jimma, and East Wollega zones [7, 8, 21]. Twenty-eight medicinal plants were documented from East Wollega Zone [21]; 25 medicinal plants were documented from Horro Gudurru [8]; and 21, 20, 19, and 14 medicinal plants were recorded from Manna, Dedo, Kersa, and Seka Chekorsa districts of the Jimma Zone, respectively [7]. The fact that a higher number of medicinal plants were reported from the study district as compared to some neighboring districts or zones could be attributed to the rich livestock population in the district as reported in Tamiru et al. [14]. The fact that Euphorbiaceae and Lamiaceae contributed a higher number of plants to the medicinal plants flora of the study district may be related to their respective sizes in terms of the number of species each comprises in the flora of Ethiopia. Euphorbiaceae and Lamiaceae are among the largest families in the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea containing 209 and 184 species, respectively [22, 23]. The relative richness of the two families in medicinal plants may also be related to their richness in some active principles. The common use of herbaceous plants in the study district in the preparation of remedies could be attributed to the better abundance of the same as compared to other life forms as was also observed by the investigators of the study during their visits to the study area. The common use of herbs was also reported by other ethnoveterinary studies carried out in Midakegn District of West Shewa Zone [12] and some districts of Horro Guduru [8] and East Wollega [21] zones. The use of a high number of medicinal plants for the treatment of gastrointestinal complaints could be an indication of a high prevalence of this ailment category in the study district. According to Bacha and Taboge [17], gastrointestinal ailments are among the commonly occurring diseases in the study district.

4.2. Part Used, Methods of Preparation, and Route of Administration

Leaf was the most commonly used plant part in the preparation of remedies, which is in agreement with studies conducted in other parts of the country [8, 12, 21]. The wider use of leaves may be related to the fact it is much easier and faster to prepare remedies from such plant part. Most remedies in the study district were prepared by crushing, a method which is also commonly applied in the preparation of remedies elsewhere in the country [1, 13, 24–26]. The common use of crushing in the preparation of remedies may be related to its easiness. Most remedies in the study district are prepared from fresh plants materials and other studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia [8, 10, 13, 26, 27] also reported the common use of fresh materials. The wider use of fresh materials in remedy preparation could indicate the availability of most of the needed plant parts in the vicinity any season of the year. The common use of water as a diluent in processing remedies in the study district may be related to its property in dissolving many active compounds. The fact that most remedies were administered orally could be attributed to the common occurrence of gastrointestinal tract ailments in the study district. A study reveals that gastrointestinal ailments are among the top animal health problems in the study district [17].

4.3. Informant Consensus Factor

Ophthalmological, dermatological, febrile, and gastrointestinal ailments were the major disease categories that scored high ICF values in the study district and medicinal plants used against such ailments categories could be considered as good candidates for further pharmacological evaluation as they are expected to exhibit better potency as compared with those that are used to treat ailment categories with low ICF values [18].

4.4. Habitat

The majority of the claimed medicinal plants in the study district were found to be uncultivated ones, which is in agreement with reports of other studies conducted elsewhere in the country [8, 13, 26, 28]. The fact that the majority of medicinal plants were harvested from the wild indicates a serious threat to the same amid ongoing deforestation and habitat destruction that are taking place in the country.

4.5. Comparison of Knowledge of Medicinal Plants between Different Social Groups

The fact that older people in the study district had better knowledge of medicinal plants as compared with the younger ones may indicate the problem medicinal plant knowledge transfer, across generations, is facing, which could be related to lack of interest by the younger generation to practice traditional medicine due to acculturation. Other studies conducted elsewhere in different parts of the country also demonstrated that older people have a better knowledge of medicinal plants as compared with younger ones [29, 30]. The reason why males had better knowledge of medicinal plants as compared with females could be related to the fact that, in Ethiopia, traditional medical practice is dominated by men which is reflected in the choice of knowledgeable people to transfer their knowledge along the male line [31]. There was no difference in knowledge of medicinal plants between illiterate people and literate ones as was also reported by a study conducted in Ankober District of Amhara Region of Ethiopia [30].

5. Conclusion

The present study revealed rich knowledge on the use of medicinal plants for the treatment of various livestock ailments in Ambo District. It was found out that the highest number of medicinal plants was used to manage gastrointestinal complaints, an indication of a high prevalence of this ailment category in the area. Most remedies in the study district were prepared by crushing leaves and this may be related to their easiness. The majority of the claimed medicinal plants were found to be harvested from the wild and this indicates their serious threat amid ongoing deforestation and habitat destruction taking place in the country. The highest ICF value was obtained for ophthalmological problems. Thus, priority for evaluation should be given to medicinal plants used in the treatment of ophthalmological problems as medicinal plants used in the treatment of ailments with high ICF values are considered to be good candidates for further pharmacological studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the informants in Ambo District for their unreserved willingness to share their traditional knowledge with them on the use of plants for ethnoveterinary purposes. The authors thank Ambo District Administration Office and local elders for their support in the selection of informants, and Ambo District Agriculture Office for the provision of information regarding the number of veterinary clinics and animal health professionals in the district. Last but not least, the authors thank Dr. Tadesse Eguale (veterinarian at ALIPB, Addis Ababa University) for his assistance in translating local names of livestock ailments into their English equivalents, based on descriptions of symptoms and grouping the same into major disease groups. This research was financially supported by the Office of the Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer of Addis Ababa University.

Data Availability

Ethnoveterinary data were stored in a computer available at Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology (ALIPB). Readers may request ALIPB for permission to get access to the data.

Disclosure

This manuscript is available online as a preprint and can be accessed through the link https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-5193/v1. The role of the office is to support academic staff and students to conduct problem-solving research and publish their findings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Belayneh A., Asfaw Z., Demissew S., Bussa F. Medicinal plants potential and use by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Erer Valley of Babile Woreda, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2012;8:12–16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elizabeth A., Hans W., Zemede A., Tesfaye A. The current status of knowledge of herbal medicine and medicinal plants in Fiche, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2014;10 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynam T., De Jong W., Sheil D., Kusumanto T., Evans K. A review of tools for incorporating community knowledge, preferences, and values into decision making in natural resources management. Ecology and Society. 2007;12:p. 5. doi: 10.5751/es-01987-120105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abebe D. Traditional medicine in Ethiopia: the attempts being made to promote it for effective and better utilisation. SINET: Ethiopian Journal of Science. 1986;9(Suppl):61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giday M., Asfaw Z., Woldu Z. Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;124:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asfaw Z. The role of home gardens in the production and conservation of medicinal plants. Proceedings of Workshop on Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants in Ethiopia; May 2001; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Institute of Biodiversity Conservation and Research; pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yigezu Y., Berihun D., Yenet W. Ethnoveterinary medicines in four districts of Jimma zone, Ethiopia: cross sectional survey for plant species and mode of use. BMC Veterinary Research. 2014;10 doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birhanu T., Abera D. Survey of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants at selected Horro Gudurru districts, western Ethiopia. African Journal of Plant Science. 2015;9:185–192. doi: 10.5897/ajps2014.1229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romha G., Dejene T. A., Telila L. B., Bekele D. F. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants: preparation and application methods by traditional healers in selected districts of southern Ethiopia. Veterinary World. 2015;8(5):674–684. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.674-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammed C., Abera D., Woyessa M., Birhanu T. Survey of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants in Melkabello district, Eastern Harerghe Zone, Eastern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal. 2016;20:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fufa T., Melaku M., Bekele T., Regassa T., Kassa N. Ethnobotanical study of ethnoveterinary plants in kelem Wollega zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2017;1:307–317. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitata G., Abdeta D., Amante M. Ethnoknowledge of plants used in veterinary practices in Midakegn district, west Showa of Oromia region, Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies. 2017;5:282–288. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekele F., Lulu D., Goshu D., Addisu R. Survey of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants at dale Sadi districts of Oromia Regional state, western Ethiopia. Journal of Natural Sciences Research. 2018;8 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamiru F., Dagmawit A., Askale G., Solomon S., Morka D., Waktole T. Prevalence of ectoparasite infestation in chicken in and around Ambo town, Ethiopia. Iranian Journal of Veterinary Science and Technology. 2014;5:p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunde B. Addis Ababa, Ethopia: Addis Ababa University; 2014. Investigation of some engineering properties of soils found in ambo town, ethiopia. M.Sc thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zewdu E., Teshome Y., Makwoya A. Bovine hydatidosis in Ambo municipality Abattoir, West Shoa, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal. 2010;14 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacha D., Taboge E. Addis Ababa, Ethopia: EARO; 2003. Enset production in West Shewa Zone. Research Report No 49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrich M., Ankli A., Frei B., Weimann C., Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;47(11):1859–1871. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrade-Cetto A., Heinrich M. From the field into the lab: useful approaches to selecting species based on local knowledge. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2011;2:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lautenschläger T., Monizi M., Pedro M., et al. First large-scale ethnobotanical survey in the province of Uíge, northern Angola. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2018;14:p. 51. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0238-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tadesse B., Mulugeta G., Fikadu G., Sultan A. Survey on ethno-veterinary medicinal plants in selected woredas of East Wollega zone, western Ethiopia. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare. 2014;4:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert M. G. Euphorbiaceae. In: Edwards S., Tadesse M., Hedberg I., editors. Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Volume 2, Part 2: Canellaceae to Euphorbiaceae. Addis Ababa, Ethopia: The National Herbarium; 1995. pp. 265–380. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryding O. Lamiaceae. In: Hedberg I., Kelbessa E., Edwards S., Demissew S., Persson E., editors. Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Volume 5: Gentianaceae to Cyclocheilaceae. Addis Ababa, Ethopia: The National Herbarium; 2006. pp. 516–604. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yirga G., Teferi M., Brhane G., Amare S. Plants used in ethnoveterinary practices in Medebay-Zana district, Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2012;6:433–438. doi: 10.5897/jmpr11.1133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teklay A. Traditional medicinal plants for ethnoveterinary medicine used in kilte Awulaelo district, Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia. Advancement in Medicinal Plant Research. 2015;3:137–150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Usmane A., Birhanu T., Redwan M., Sado E., Abera D. Survey of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants at selected districts of Harari Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal. 2016;20(1):1–22. doi: 10.4314/evj.v20i1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lulekal E., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E., Van Damme P. Ethnoveterinary plants of Ankober district, North Shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2014;10(1):p. 21. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giday M., Teklehaymanot T. Ethnobotanical study of plants used in management of livestock health problems by Afar people of Ada’ar District, Afar Regional State, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2013;9(1):p. 8. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gedif T., Hahn H.-J. The use of medicinal plants in self-care in rural central Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;87(2-3):155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lulekal E., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E., Van Damme P. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used for human ailments in Ankober district, North Shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2013;9(1):p. 63. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teklehaymanot T. Ethnobotanical study of knowledge and medicinal plants use by the people in Dek Island in Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;124(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Ethnoveterinary data were stored in a computer available at Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology (ALIPB). Readers may request ALIPB for permission to get access to the data.