Abstract

Background

Clinically, a distinction is made between types of rotator cuff tear, traumatic and non-traumatic, and this sub-classification currently informs the treatment pathway. It is currently recommended that patients with traumatic rotator cuff tears are fast tracked for surgical opinion. However, there is uncertainty about the most clinically and cost-effective intervention for patients with traumatic rotator cuff tears and further research is required.

SPeEDy will assess the feasibility of a fully powered, multi-centre randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test the hypothesis that, compared to surgical repair (and usual post-operative rehabilitation), a programme of physiotherapist-led exercise is not clinically inferior, but is more cost-effective for patients with traumatic rotator cuff tears.

Methods

SPeEDy is a two-arm, multi-centre pilot and feasibility RCT with integrated Quintet Recruitment Intervention (QRI) and further qualitative investigation of patient experience. A total of 76 patients with traumatic rotator cuff tears will be recruited from approximately eight UK NHS hospitals and randomly allocated to either surgical repair and usual post-operative rehabilitation or a programme of physiotherapist-led exercise. The QRI is a mixed-methods approach that includes data collection and analysis of screening logs, audio recordings of recruitment consultations, interviews with patients and clinicians involved in recruitment, and review of study documentation as a basis for developing action plans to address identified difficulties whilst recruitment to the RCT is underway. A further sample of patient participants will be purposively sampled from both intervention groups and interviewed to explore reasons for initial participation, treatment acceptability, reasons for non-completion of treatment, where relevant, and any reasons for treatment crossover.

Discussion

Research to date suggests that there is uncertainty regarding the most clinically and cost-effective interventions for patients with traumatic rotator cuff tears. There is a clear need for a high-quality, fully powered, RCT to better inform clinical practice. Prior to this, we first need to undertake a pilot and feasibility RCT to address current uncertainties about recruitment, retention and number of and reasons for treatment crossover.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04027205) – Registered on 19 July 2019. Available via

Keywords: Surgery, Physiotherapy, Exercise, Rotator cuff tear, Shoulder, Randomised controlled trial

Introduction

Background and rationale

Shoulder pain presents a significant personal, social and economic burden and impacts on work, ability to undertake leisure and household tasks and causes disturbed sleep [1]. Tears of the rotator cuff are regarded as a significant cause of shoulder pain and rates of surgery to repair the torn rotator cuff have risen approximately 200% over recent years across Europe and the USA [2–5]. In the UK NHS, 8838 surgical repairs of the rotator cuff were undertaken in 2018/2019 with approximately one-third undertaken for traumatic tears [6]. Depending on complexity, the cost of surgical repair ranges from £3676 to £6419 [7] meaning that direct NHS treatment costs alone range from £26.6 to £51.4 million annually, and £10.8 to £18.9 million specifically for traumatic rotator cuff tears.

Different treatment pathways are proposed in the current British Elbow & Shoulder Society and British Orthopaedic Association guidelines [8] for patients presenting with non-traumatic as opposed to traumatic rotator cuff tears. These guidelines recommend that patients with traumatic rotator cuff tears are fast tracked for surgical opinion. Three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 252) comparing surgery to non-surgical treatment for rotator cuff tears have been undertaken and synthesised in a systematic review (SR) [9]. The review concluded that, although the evidence is limited in terms of quality, current research suggests no difference in clinical outcomes at 1 year between surgery and non-surgical treatment. However, of the 252 patients included in the SR, only 40 (16%) were diagnosed with traumatic tears of the rotator cuff (24 randomised to surgery; 16 to physiotherapist-led exercise). Since the publication of this SR, one further RCT (n = 58) focusing specifically on traumatic rotator cuff tears has been published [10]. This RCT compared surgical repair with a programme of physiotherapist-led exercise for acute traumatic rotator cuff tears located mainly within supraspinatus [10]. At 12 months, there was no significant between-group difference in terms of shoulder pain and function. Re-tear was reported in 6.5% of participants undergoing repair and tear size progression greater than 5 mm in 29.2% of participants undergoing the programme of physiotherapist-led exercise [10]. Hence, there is uncertainty about optimal interventions for traumatic rotator cuff tears based on evidence from a limited number of patients and from RCTs with relatively short-term follow-up.

Despite this uncertainty from RCTs, other reasons for current guidelines recommending fast track for surgical opinion for people with traumatic rotator cuff tears include a concern that a delayed surgical repair is more technically challenging and that delay risks poorer clinical outcomes. Several non-randomised studies have evaluated the impact of time to surgery on clinical outcomes. Findings vary considerably with some recommending surgery within 4 months of symptom onset [11], some 6 months [12] and some 24 months [13], yet others conclude that time to surgery is not a critical factor [14]. Thus, there is considerable uncertainty and given that asymptomatic rotator cuff tears are very common, it is also difficult to attribute tears of the rotator cuff to recent trauma with confidence [15]. Imaging for shoulder pain following trauma may in fact be identifying an existing asymptomatic rotator cuff tear. Another reason proposed in support of current guidelines recommending fast track for surgical opinion relates to progression, i.e. the increasing size of a rotator cuff tear if not operated on [16]. It has been reported that 42 to 47% of symptomatic tears increase in size up to 100 months follow-up [16, 17] with the greatest rate of increase in those with full-thickness tears observed in 82% versus 26% of those with partial-thickness tears [17]. Hence, most full thickness and some partial-thickness rotator cuff tears do increase in size over time, but it is apparent that some do not and, importantly, surgery is not guaranteed to prevent progression and these increases in the size of tear are not consistently associated with poorer clinical outcome in terms of pain and function [17, 18]. To further highlight uncertainty in the management of rotator cuff tears, the UKUFF trial [1] reported a 40% re-tear or failed-healing rate following surgical repair of non-traumatic rotator cuff tears but the outcomes for these patients were not clinically significantly different from those patients who did not re-tear their rotator cuff. Similar findings have also been reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies (n = 861) [19]. This suggests that the tear might not be the only source of symptoms and surgical repair, in some circumstances, might be unwarranted. In situations where both the source of symptoms and the mechanism of action of surgery are questioned, a physiotherapist-led exercise might be a credible treatment option just as it currently is for patients with non-traumatic tears [20].

The above uncertainty and lack of evidence to inform decision-making provides the justification for the current research study.

Objectives

The aim of the SPeEDy study is to determine if it is feasible to conduct a future, substantive, multi-site RCT to test the hypothesis that physiotherapist-led exercise is not inferior to surgical repair of the rotator cuff in terms of clinical outcomes but is more cost-effective.

The following objectives are to:

Determine feasibility of recruiting patients

Determine feasibility of retaining participants, including response rates to questionnaires

Determine zone of clinical equipoise, including exploration of what patient characteristics (age, size, and location of rotator cuff tear etc.) influence whether clinicians are prepared to randomise patients or not

Determine proportion and reasons for treatment crossover

Estimate the number of potential and willing sites for the future main RCT

Identify barriers and facilitators to recruitment and retention

Determine participant satisfaction with the interventions

Determine the number and nature of adverse events

Trial design

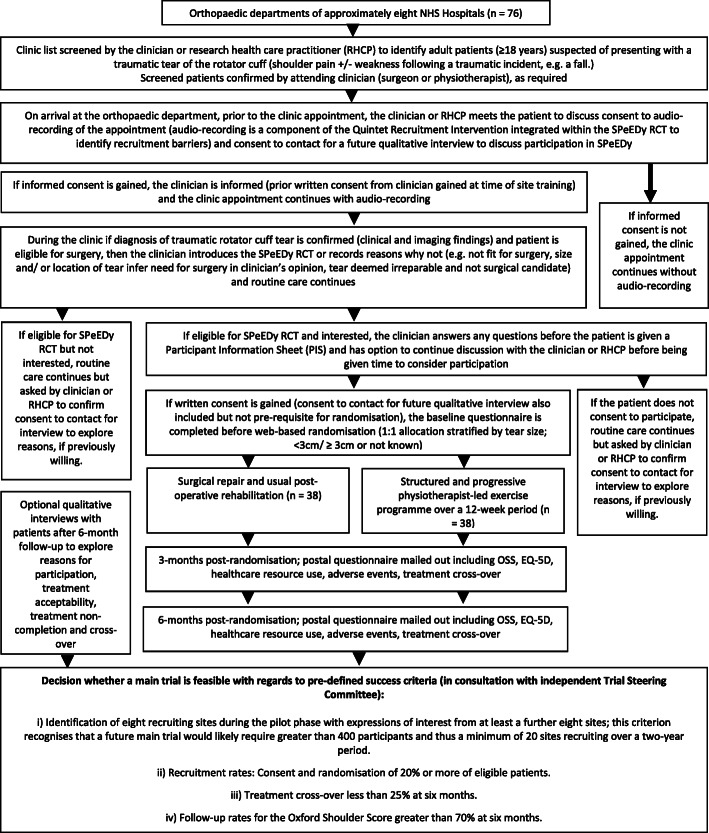

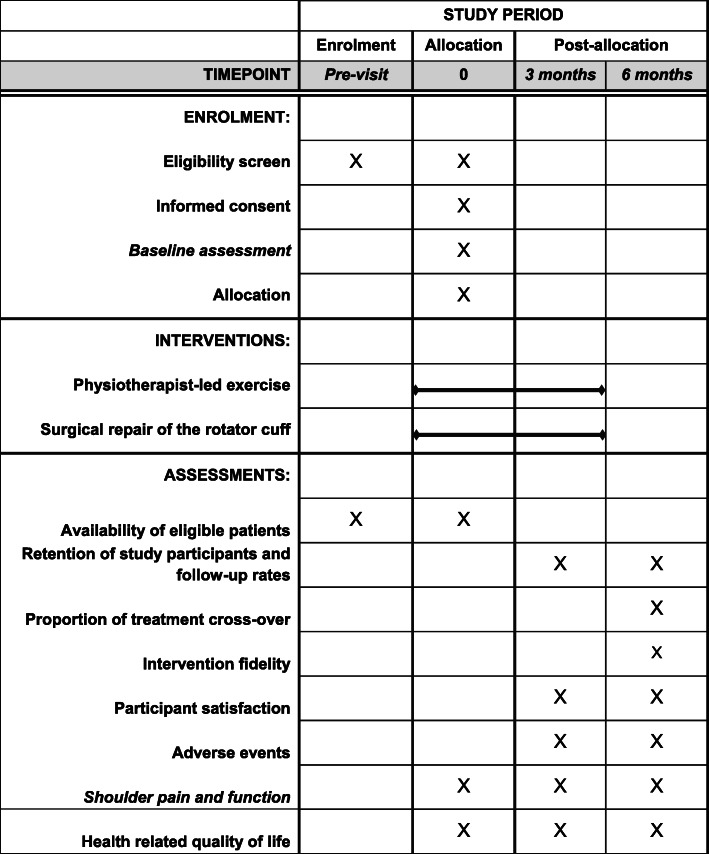

The SPeEDy study is a two-arm, multi-centre pilot and feasibility RCT (1:1 allocation ratio) with integrated Quintet Recruitment Intervention (QRI) and further qualitative investigation of patient experience (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Fig. 2.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments (SPIRIT Statement) [21]

Methods: Participants, interventions and outcomes

Study setting

Patients will be recruited from orthopaedic departments of the participating UK NHS hospitals. The study interventions will be delivered through their associated orthopaedic and physiotherapy services.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients (≥ 18 years)

Diagnosed with a symptomatic tear of the rotator cuff following a traumatic incident thought to be of sufficient force to induce a tear

Rotator cuff tear confirmed by diagnostic ultrasound or MRI scan undertaken as part of routine diagnostic workup

Eligible for rotator cuff repair surgery or a programme of physiotherapist-led exercise as determined by the attending clinician (surgeon or physiotherapist, where appropriate)

Able to return to the participating NHS hospital or associated orthopaedic and physiotherapy services (where physiotherapists have been trained in trial interventions) for post-operative rehabilitation or the programme of physiotherapist-led exercise

Able to understand English

Exclusion criteria

Not eligible for rotator cuff repair surgery or a programme of physiotherapist-led exercise as determined by the attending clinician (surgeon or physiotherapist, where appropriate)

Patients who are unable to give full informed consent

Who will take informed consent?

A local clinician or local research healthcare practitioner, who will have received appropriate training and is authorised on the trial delegation log, will support the process of informed consent. Interested and eligible patients will be required to provide written informed consent before participating (see reference below to optional Quintet Recruitment Intervention (QRI) and optional 6-month qualitative interviews). Written informed consent for the QRI will be sought at the time of attendance at the orthopaedic clinic. Consent for the RCT will be sought at the time of attendance at the orthopaedic clinic or other convenient time prior to the surgery if the patient requests more time to consider participation.

The RCT consent form indicates if the participant would like to be contacted for the purpose of the 6-month qualitative interviews. If the participant indicates yes, a researcher will contact the participant and if they agree to take part, a subsequent consent form will be signed.

Interventions

Explanation for the choice of comparators

Fast track for surgical opinion and surgical repair of the traumatic rotator cuff tear is the current standard of care and this will be compared with a programme of physiotherapist-led exercise, should this prove feasible during this pilot phase, testing the hypothesis that the latter is not clinically inferior to the standard of care but is more cost-effective.

Intervention description

Surgical repair plus usual post-operative rehabilitation

Surgical repair will be guided by the size and location of the tear and also surgeon preference, the details of which will be recorded on a specific case report form and reported accordingly. Similarly, the content of post-operative rehabilitation is variable across the UK but typically begins with a period of immobilisation using an arm sling for up to 6 weeks. After this period, rehabilitation progresses gradually with the aim of restoring movement, strength and function [22].

Structured and progressive physiotherapist-led exercise programme

The exercise programme is based on the principle of self-dosing with the aim of restoring functional capacity to a level acceptable to the individual participant. Exercise prescription is based on establishing the current functional capacity of the patient in relation to the most challenging shoulder movements and is supported over approximately six contact sessions with a physiotherapist across a 12-week period. The development process and resultant programme of physiotherapist-led exercise used in the SPeEDy study has been reported elsewhere in full [23].

Criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions

There are no special criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions.

Participants may choose to withdraw from the allocated intervention for any reason and continue a plan of treatment determined in consultation with their attending clinician.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions

Adherence to the physiotherapist-led exercise programme will be recorded in an exercise diary provided to the patient and monitored by the physiotherapist. No further strategies beyond usual encouragement will be used.

Relevant concomitant care permitted or prohibited during the trial

No special provisions.

Provisions for post-trial care

None beyond standard care within the NHS.

Outcomes

Feasibility outcomes

Numbers of patients screened, number eligible, number approached, number consenting, number randomised and number accepting allocation and reasons for patients not being eligible, approached or declining participation

Numbers of participants receiving and completing the allocated intervention

Follow-up response rates to questionnaires at 3 and 6 months post-randomisation (including Oxford Shoulder Score and EQ-5D-5L)

Determine reasons for not approaching potentially eligible patients and how this varies between clinicians

Numbers of participants receiving intervention (surgery or PT-led exercise) other than that which was allocated to determine proportion of participants who crossover

Numbers of sites agreeing to participate and numbers of additional sites who are interested in participating in the main trial

Participant satisfaction with the interventions on a five-point ordinal scale; very satisfied/satisfied/neutral/dissatisfied/very dissatisfied

Barriers and facilitators to recruitment, retention and treatment crossover (qualitative data; audio recording and individual interviews)

Clinical outcomes

Pain and disability assessed using the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) at baseline, 3 and 6 months post-randomisation by post with telephone call for minimum data collection if no response to reminder postal questionnaire

Health-related quality of life assessed using the EQ-5D-5L at baseline, 3 and 6 months post-randomisation by post with telephone call for minimum data collection if no response to reminder postal questionnaire

Days lost from work due to the shoulder problem at 3 and 6 months post-randomisation via postal questionnaire

Time taken to return to driving, if applicable, via questionnaire at 3 and 6 months post-randomisation via postal questionnaire

Number and type of adverse events for up to 6 months post-randomisation via patient self-report questionnaire or telephone Minimal Data Collection (MDC) at 3 and 6 months and via surgeon, physiotherapist or GP report

Self-report data relating to further healthcare resource use, including NHS- and private-borne service, and medication costs will also be collected.

Participant timeline

See s. 1 and 2.

Sample size

Randomising 76 participants will enable the 1-sided lower 90% confidence limit for the follow-up rate to be estimated within about 6% of the anticipated 80% level at 6 months. Further, a sample size of about 76, allowing for dropout, will be sufficient to allow precise calculation of estimates of standard deviation around the OSS for the main RCT [24].

Additionally, with reference to treatment crossover of less than 25% (principal concern relates to those randomised to the physiotherapist-led exercise programme crossing over to surgery), randomising 38 participants to the physiotherapist-led exercise programme enables precise 1-sided upper confidence limits (e.g. around 8% above the desired upper level of around 15% for a 90% upper confidence limit).

Recruitment

Potential participants will be identified when the diagnosis of symptomatic traumatic rotator cuff tear is made (sudden onset of shoulder pain and weakness following a traumatic incident with a tear confirmed by ultrasound or MRI) and surgery is considered a treatment option. The patient pathway is variable between sites but, typically, this diagnosis and identification of the two possible management options will be made by an orthopaedic surgeon, or physiotherapist, who will subsequently introduce the RCT to the patient. If the patient expresses interest, further discussion will ensue between the patient and the clinician or research healthcare practitioner (depending on availability) who will provide them with a study information pack, by hand or in the post, and follow this up with a discussion, face-to-face or over the telephone.

Assignment of interventions: Allocation

Sequence generation

Participants will be allocated on a 1:1 ratio, stratified by tear size (large tear ≥ 3 cm/small to medium sized tear < 3 cm/or not known), using mixed-block randomisation.

Concealment mechanism

Randomisation will be undertaken remotely using web-based randomisation to ensure allocation concealment provided by Derby Clinical Trials Support Unit.

Implementation

The participant will be informed of the allocation by the clinician or research healthcare practitioner, depending on availability, and will then access the interventions as per usual treatment pathways, including being placed on a waiting list for surgery or physiotherapy.

Assignment of interventions: Blinding

Who will be blinded

No measures to blind participants, clinicians, research team or oversight committees will be implemented.

Data collection and management

Plans for assessment and collection of outcomes

Local sites will complete screening logs and participants will complete the baseline questionnaire, including demographic data, the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) and EQ-5D-5L. The OSS is a 12-item shoulder-specific self-report measure of shoulder pain and function primarily for the assessment of outcome of shoulder surgery in RCTs [25]. The OSS is reliable, valid, responsive and acceptable to patients [1, 25, 26]. The items refer to the past 4 weeks with five ordinal response options scored from 0 to four, with four representing the best outcome. When the 12 items are summed, this produces an overall score ranging from 0 to 48, with 48 being the best outcome.

The EQ-5D-5L is a generic measure of health-related quality of life that provides a single index value for health status that can be used for the purpose of clinical and health economic evaluation [27]. The EQ-5D-5L consists of questions relating to five health domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), and respondents rate their degree of impairment using five response levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems) [27]. EQ-5D is the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE) preferred measure of health-related quality of life in adults.

Follow-up at 3 and 6 months post-randomisation will be via postal questionnaire.

Plans to promote participant retention and complete follow-up

Follow-up processes include reminders and MDC via telephone if questionnaires are not returned within 2 and 4 weeks respectively.

Data management

All participants are given an individual study number that will be used on all case report forms for that participant. Case report forms will be processed and stored securely.

Confidentiality

All collected information will be kept strictly confidential and will be stored in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and retained in accordance with the latest Directive on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and local policy.

Statistical methods

Statistical methods for primary and secondary outcomes

As this is a pilot and feasibility RCT, the main analysis will focus on process outcomes, including consent rate, retention rate and follow-up rates. Means and confidence intervals of the OSS will be calculated in order to inform the sample size calculation for the main RCT. Analysis will be undertaken using the IBM SPSS statistics package (https://www.ibm.com/uk-en/products/spss-statistics). A detailed data analysis plan will be agreed with the independent trial steering committee (TSC) before any analysis is undertaken.

The following success criteria will be used to decide on whether to proceed to developing a main RCT:

-

i)

Identification of eight recruiting sites during the pilot phase with expressions of interest from at least a further eight sites

-

ii)

Recruitment rates: Consent and randomisation of 20% or more of eligible patients

-

iii)

Treatment crossover less than 25%, of those randomised, at 6 months in each of the two treatment groups

-

iv)

Follow-up rates for the OSS greater than 70% at 6 months

Interim analyses

No interim analyses are planned.

Methods for additional analyses (e.g. subgroup analyses)

No additional analyses are planned.

Methods in analysis to handle protocol non-adherence and any statistical methods to handle missing data

The primary analysis will be intention to treat. However, an additional per-protocol analysis will be undertaken to account for any participants who did not receive the allocated intervention within the study period, with no account taken of protocol non-adherence beyond reporting of treatment crossover.

The Quintet recruitment intervention

RCTs can be challenging to recruit to, with clear obstacles including a lack of time and strong patient preferences, but also hidden challenges including tensions for clinicians and challenges around assuming a position of equipoise [28, 29]. However, without systematic evaluation, hidden challenges remain unknown and opportunities to change RCT processes, for example, study training and documentation, are lost to the potential detriment to the RCT. In recognition of this, the QRI will be integrated within the SPeEDy RCT to understand the challenges associated with recruitment and develop action plans to address these challenges rapidly whilst recruitment is underway.

The QRI is a mixed-methods approach that includes data collection and analysis of screening and eligibility logs, audio recordings of recruitment consultations (i.e. consultations during which recruitment to the RCT is discussed), individual interviews with patients and clinicians involved in recruitment, and review of study documentation as a basis for developing action plans to address identified difficulties whilst recruitment to the RCT is underway [30, 31]. It has been shown to facilitate recruitment to the most challenging RCTs, including orthopaedic RCTs [29, 32]. A targeted QRI, investigating recruiter information provision, patient responses to this information and recruitment performance across recruiters/sites, will be integrated within the SPeEDy RCT over the recruitment period to enable barriers to recruitment to be identified and any changes to the recruitment process to be made and re-evaluated.

In line with the SEAR (Screening, Eligibility, Approached, Randomised) framework [33], screening and eligibility logs will detail all patients screened (by the research healthcare practitioner (RHCP) and attending clinician) to identify how many are eligible, approached, accepting randomisation and the allocated intervention, alongside reasons not eligible, approached or accepting randomisation. These will be completed at the clinical site.

Clinic and recruitment appointments involving discussion of the SPeEDy RCT will be audio recorded and then subjected to targeted data extraction and transcription, focusing analysis on discussion of issues relevant to recruitment to the SPeEDy RCT, to investigate how recruiters present the study to patients and how patients respond.

In-depth, semi-structured interviews will be conducted, guided by topic guides with a purposive sample of patients and clinicians involved in identifying patients and RHCPs (responsible for explaining the trial and obtaining informed consent) from selected sites. Selection of sites will be determined by willingness to participate in the QRI and determined by relative recruitment performance, i.e. high and low-recruiting sites.

Given the responsive and iterative nature of the QRI, it is not realistic to pre-specify a required number of participants. But, we will aim to sample data from four out of the eight-hospital sites including six to 12 clinicians and 12‑20 patients or until saturation is reached. Data collection will be limited to the pre-specified maximum 9-month period. However, data collection will cease if no new themes emerge from the ongoing analysis prior to this time point.

Data from the screening and eligibility logs will be analysed descriptively to identify differences between sites and points in the recruitment pathway where patients at particular sites are ‘lost’ to recruitment. Findings from this analysis will guide sampling for audio recording of recruitment discussions and interviews.

Audio recordings of clinic and recruitment appointments will be analysed using thematic, content and targeted conversation analysis techniques with the aim of understanding the challenges to recruitment [34]. In tandem with this, data from individual interviews will be analysed using constant comparison techniques which involves detailed coding followed by comparison of emerging themes and codes within transcripts and across the dataset looking for shared or disparate views. Findings will be presented anonymously.

Study documentation, including PIS and consent forms and Trial Management Group (TMG)/Trial Steering Committee (TSC) meeting minutes, will be reviewed with reference to the findings from the interviews and recruitment appointments. Data from screening logs, audio recordings, interviews and study documentation will be triangulated to identify where findings are confirmed across data sources.

Upon completion of this analysis, an action plan will be generated to address factors that appear to be hindering recruitment. Previous reports of the outcome of the QRI have identified generic and study-specific barriers to recruitment which can be addressed through bespoke action plans [29]. Also in some instances, the QRI has provided clear reasons why recruitment to the RCT might not be achievable [29]. Once the action plan is agreed, where relevant, study documentation will be amended and further training offered to recruiters across all of the hospital sites. Post-implementation of the plan, a further evaluation of the recruitment process will be undertaken using feasibility outcome data described in this protocol.

Patient experience of trial participation

Following the 6-month follow-up point, a further sample of patient participants will be purposively sampled from both intervention groups and interviewed to explore reasons for initial participation, treatment acceptability, reasons for non-completion of treatment, where relevant, and any reasons for treatment crossover.

Patients will be purposefully sampled with respect to allocated group, change in pain and disability status according to the OSS, whether the allocated treatment was completed or not and in relation to treatment crossover. Patients will be able to decline participation in the interviews yet still be involved in the RCT.

The interviews will be based not only on semi-structured topic guides developed in relation to the pre-specified aims but also with our patient and public involvement group (approximately 30-min telephone interview). It is expected that approximately 20 patients will be sufficient to attain rich data. Telephone interviews will be conducted, audio recorded and transcribed ad verbatim.

As with the QRI qualitative data analysis, interviews will be analysed thematically.

Plans to give access to the full protocol, participant level-data and statistical code

The full protocol is available via clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04027205). In the first instance, further requests for data can be made via the corresponding author.

Oversight and monitoring

Composition of the coordinating centre and trial steering committee

The chief investigator (CL) is responsible for the conduct of the study and will be supported by the TMG comprising members of the research team.

An independent TSC will oversee the study and includes an independent chair and four further independent members comprising a statistician, lay and clinical representatives. The CI, senior statistician and Trial Manager will attend the TSC meetings and present and report progress. TSC meetings will be scheduled approximately annually.

Composition of the data monitoring committee, its role and reporting structure

Since this is a pilot RCT with no planned interim statistical analysis, a Data Monitoring Committee has not been formed and the TSC has agreed to take responsibility for reviewing the safety of the trial including advice regarding progression to a main RCT with reference to the pre-specified progression criteria.

Adverse event reporting and harms

Number and type of adverse events for up to 6 months post-randomisation will be collected via patient self-report questionnaire or telephone MDC at 3 and 6 months and via surgeon, physiotherapist or GP report.

Frequency and plans for auditing trial conduct

Independent TSC meetings will be scheduled approximately annually.

Plans for communicating important protocol amendments to relevant parties (e.g. trial participants, ethical committees)

Funders, sponsors and NHS Research & Development Offices will be notified routinely and appropriate approvals gained and communicated as required by them and by the study sponsor.

Dissemination plans

The results of the SPeEDy study will be published in peer-reviewed journals, presented at relevant conferences and disseminated to clinicians and patients, as appropriate.

Discussion

Despite a dearth of research evidence and uncertainty regarding the most clinical and cost-effective treatment interventions for patients with traumatic rotator cuff tears, current national guidelines suggest that people with suspected traumatic tears should seek urgent surgical opinion [8]. It remains unclear whether such an approach should be recommended in preference to, for example, non-surgical assessment and management. Recognising current uncertainties, SPeEDy has been developed as a pilot and feasibility RCT with integrated QRI and further qualitative interviews to investigate the barriers, and facilitators, to recruitment, intervention delivery and fidelity, and clinical equipoise from the perspectives of patients and clinicians. We expect recruitment to be challenging but there is a clear need for a high-quality, fully powered, RCT to compare surgery and usual post-operative rehabilitation versus a programme of physiotherapist-led exercise for a defined group of patients presenting with traumatic rotator cuff tears. This pilot and feasibility RCT will determine the feasibility of a fully powered RCT, including whether it is possible to recruit patients and retain participants in their allocated group.

Study status

The SPeEDy study (protocol version 1.0 dated 05 August 2019) opened to recruitment on 3 March 2020, and was scheduled to complete recruitment by 31 January 2021. However, recruitment was paused due to COVID-19 on 16 March 2020, re-opened on 3 August 2020, but then paused again on 4 October 2020, to enable transfer of the study sponsor.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of Stacey Lalande, Aidan O’Shea, Karen Larsen, Larry Koyoma, Laura Hedley, Elaine Wilmore, Ellie Richardson, Gordon Smith, James Roberts, Rachel Winstanley, Catrin Astbury, Lisa Pitt, Andrew Cuff and members of the Research User Group from the Primary Care Centre Versus Arthritis, Keele University who contributed to the development of the physiotherapist-led exercise intervention. This study is sponsored by University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust.

Authors’ contributions

CL, NEF and JW conceived of the study and were involved, alongside SBW, DB and AR in developing the design and protocol. CL secured funding for the study. CL drafted the manuscript and all other authors reviewed and provided feedback on drafts. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

CL is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Post-Doctoral Fellowship (PDF-2018-11-ST2-005) for this research project.

NEF was supported through an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-011-015) and is an NIHR Senior Investigator.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speaker and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and materials

Data required to support the protocol will be supplied on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been reviewed and a favourable opinion provided by the South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 19/SS/0098). All participants provide written consent to participate after receiving a full written and verbal explanation of the study’s aims, procedures and risks.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication is not applicable as there are no identifying images of other personal details of participants presented.

Competing interests

AR receives educational and research grants from DePuy J&J Ltd. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carr AJ, Cooper CD, Campbell MK, Rees JL, Moser J, Beard DJ, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of open and arthroscopic rotator cuff repair [the UK rotator cuff surgery (UKUFF) randomised trial] Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2015;19(80):1–217. doi: 10.3310/hta19800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ensor K, Kwon Y, DiBeneditto R, Zuckerman J, Rokito A. The rising incidence of rotator cuff repairs. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2013;22(12):1628–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paloneva J, Lepola V, Äärimaa V, Joukainen A, Ylinen J, Mattila VM. Increasing incidence of rotator cuff repairs--a nationwide registry study in Finland. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:189. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0639-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colvin A, Egorova N, Harrison A, Moskowitz A, Flatow E. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Jt Surg - Am. 2012;94(3):227–233. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maffulli N, Longo U. Conservative management for tendinopathy: is there enough scientific evidence? Rheumatology. 2008;47:390–391. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hospital Episode Statistics. Hospital admitted patient care activity [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 27]. Available from: Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2015-16.

- 7.NHS Improvement. 2019/20 National Tariff Workbook [Internet]. National tariff payment system. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/national-tariff/#h2-201920-national-tariff-payment-system.

- 8.Kulkarni R, Gibson J, Brownson P, Thomas M, Rangan A, Carr AJ, et al. BESS/BOA patient care pathways: subacromial shoulder pain. Shoulder Elb. 2015;7(2):135–143. doi: 10.1177/1758573215576456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryösä A, Laimi K, Äärimaa V, Lehtimäki K, Kukkonen J, Saltychev M. Surgery or conservative treatment for rotator cuff tear: a meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;8288(August):1–7. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1198431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranebo MC, Björnsson Hallgren HC, Holmgren T, Adolfsson LE. Surgery and physiotherapy were both successful in the treatment of small, acute, traumatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2020;29(3):459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen SA, Murphy TP. The timing of rotator cuff repair for the restoration of function. J Shoulder Elb Surg [Internet]. 2011;20(1):62–68. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2010.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Duncan NS, Booker SJ, Gooding BWT, Geoghegan J, Wallace WA, Manning PA. Surgery within 6 months of an acute rotator cuff tear significantly improves outcome. J Shoulder Elb Surg [Internet]. 2015;24(12):1876–1880. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2015.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Tan M, Lam PH, Le BT, Murrell GA. Trauma versus no trauma: an analysis of the effect of tear mechanism on tendon healing in 1300 consecutive patients after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;25(1):12–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Zhaeentan S, Von Heijne A, Stark A, Hagert E, Salomonsson B. Similar results comparing early and late surgery in open repair of traumatic rotator cuff tears. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(12):3899–3906. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teunis T, Lubberts B, Reilly B, Ring D. A systematic review and pooled analysis of the prevalence of rotator cuff disease with increasing age. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2014;23:1913–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto N, Mineta M, Kawakami J, Sano H, Itoi E. Risk factors for tear progression in symptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of 174 shoulders. Am J Sports Med 2017;45(11):2524–2531. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0363546517709780. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kim Y, Kim S, Bae S, Lee H, Jee WH, Park CK. Tear progression of symptomatic full - thickness and partial - thickness rotator cuff tears as measured by repeated MRI. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(17):2073–2080. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mall NA, Kim HM, Keener JD, Steger-May K, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, et al. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2010;92(16):2623–2633. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell RD, Knight JR, Mulligan E, Khazzam MS. Structural integrity after rotator cuff repair does not correlate with patient function and pain: a meta-analysis. J Bone Jt Surg 2014;96(4):265–271. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9355(14)74053-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Sealey P, Lewis J. Rotator cuff tears: is non-surgical management effective? Phys Ther Rev. 2016;3196(December):0. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10833196.2016.1271504.

- 21.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche P, Krleža-Jerić K, Hróbjartsson A, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:200–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Littlewood C, Bateman M. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: a survey of current UK practice. Shoulder Elb. 2015;7:193–204. doi: 10.1177/1758573215571679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Littlewood C, Astbury C, Bush H, Gibson J, Lalande S, Miller C, et al. Development of a physiotherapist-led exercise programme for traumatic tears of the rotator cuff for the SPeEDy study. Physiotherapy. 2020; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson J, Rogers K, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. The Oxford shoulder score revisited. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:119–123. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about shoulder surgery. J Bone Jt Surg. 1996;78:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Reenen M, Janssen B. EQ-5D-5L User guide basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/EQ-5D-5L_UserGuide_2015.pdf.

- 28.Rooshenas L, Elliott D, Wade J, Jepson M, Paramasivan S, Strong S, et al. Conveying equipoise during recruitment for clinical trials: qualitative synthesis of clinicians’ practices across six randomised controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):1–24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan JL, Rooshenas L, Jepson M, Elliott D, Wade J, Avery K, et al. Optimising recruitment and informed consent in randomised controlled trials: the development and implementation of the Quintet Recruitment Intervention (QRI). Trials. 2016;17(1):283. Available from: http://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-016-1391-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Wade J, Donovan JL, Athene Lane J, Neal DE, Hamdy FC. It’s not just what you say, it’s also how you say it: opening the “black box” of informed consent appointments in randomised controlled trials. Soc Sci Med 2009;68(11):2018–2028. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Wade J, Elliott D, Avery KNL, Gaunt D, Young GJ, Barnes R, et al. Informed consent in randomised controlled trials: development and preliminary evaluation of a measure of Participatory and Informed Consent (PIC) Trials. 2017;18(1):327. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2048-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beard DJ, Rees JL, Cook JA, Rombach I, Cooper C, Merritt N, et al. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain (CSAW): a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, three-group, randomised surgical trial. Lancet. 2017;6736(17):1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32457-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson C, Rooshenas L, Paramasivan S, Elliott D, Jepson M, Strong S, et al. Development of a framework to improve the process of recruitment to Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs): The SEAR (Screened, Eligible, Approached, Randomised) framework. Trials. 2017;Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.ten Have P. Doing conversation analysis: a practical guide. 2. London, UK: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data required to support the protocol will be supplied on request to the corresponding author.