Abstract

The exact frequency and clinical determinants of spontaneous conversion (SCV) in patients with symptomatic recent-onset AF are unclear. The aim of this systematic review is to provide an overview of the frequency and determinants of SCV of AF in patients presenting at the emergency department. A comprehensive literature search for studies about SCV in patients presenting to the emergency department with AF resulted in 25 articles – 12 randomised controlled trials and 13 observational studies. SCV rates range between 9–83% and determinants of SCV also varied between studies. The most important determinants of SCV included short duration of AF (<24 or <48 hours), low number of episodes, normal atrial dimensions and absence of previous heart disease. The large variation in SCV rate and determinants of SCV was related to differences in duration of the observation period, inclusion and exclusion criteria and in variables used in the prediction models.

Keywords: Spontaneous conversion, AF, determinants, systematic review, emergency care

In patients presenting at the emergency department (ED) with symptomatic recent-onset AF, immediate restoration of sinus rhythm by pharmacological cardioversion (PCV) or electrical cardioversion (ECV) is frequently performed.[1,2] Nevertheless, most of these patients convert spontaneously to sinus rhythm without the need of additional interventions.[3–7] Several studies have indicated that rate control to manage symptoms and waiting for spontaneous conversion (SCV) to sinus rhythm is a reasonable alternative for the acute treatment of patients with recent-onset haemodynamically stable AF.[4,8]

ECV is a relatively expensive procedure and, dependent on local protocols, requires the involvement of nurses, an anaesthesiologist and a cardiologist or emergency physician. Point-of-care identification of patients with recent-onset AF who will convert spontaneously after presentation and therefore qualify for a wait-and-see approach would lower the number of PCV and ECV procedures performed in the ED setting and therefore reduce healthcare costs.

The exact frequency as well as clinical predictors of SCV to sinus rhythm in patients with symptomatic recent-onset AF are unclear. Appropriate selection of patients with a high likelihood of SCV is key to the wait-andsee approach. The present review focuses on the frequency and determinants of SCV of AF in patients presenting at the ED.

Methods

Search Methods and Study Selection

A literature search was performed to identify all articles published in English that discussed SCV to sinus rhythm in patients presenting to the ED with AF. A Boolean search of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library was performed using the phrases “spontaneous conversion”, “SCV”, “self-terminating”, “self terminating”, “wait-and-see”, “wait and see” AND “atrial fibrillation”, “AF”, “AFib” AND “recent onset”, “recent-onset”, “acute”, “paroxysmal”, “first detected”, “first-detected”. The reference lists of included articles were reviewed to identify additional articles. All original articles were included if they discussed SCV to sinus rhythm in patients presenting to the ED with AF. There were no exclusion criteria. We focused on patients who presented to the ED rather than the regular outpatient or clinical department, since this is a clinically identifiable group of patients for whom unnecessary future ED visits and cardioversion may by avoided by knowing their SCV characteristics. The literature search and screening for eligibility were performed by two of the authors (NAHAP and ANLH) independently and any disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached.

Outcome and Data Collection

The primary outcome was the SCV rate. Secondary outcomes were determinants for SCV and adverse events. Data on study design, patient characteristics, intervention and treatment were extracted.

Quality Assessment

All included articles were independently assessed for the risk of bias by the two reviewers using the Cochrane tool to assess the risk of bias for randomised controlled trials (RCT) and the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for the nonrandomised studies.[9,10] Inclusion of consecutive patients was considered to be a relevant confounding domain for the primary outcome. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Definitions

For the purpose of this review, conversion was defined as spontaneous if the patient converted to sinus rhythm without active cardioversion (either PCV or ECV), with rate control and/or placebo medication allowed. If patients were treated with placebo, digoxin, beta blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and converted to sinus rhythm, it was considered SCV for this review. The reported time until evaluation of the rhythm was used as observation time. If not reported it was considered to have no standardised observation time. Determinants of SCV were accumulated if the studies performed an analysis for determinants of SCV.

Results

Screening and Included Studies

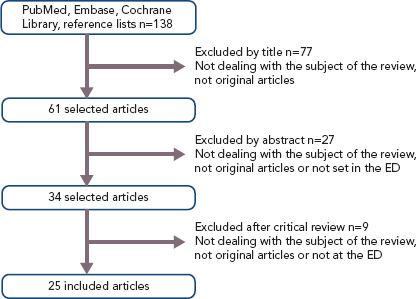

A comprehensive literature search identified 138 potentially relevant articles. After screening of title and abstract, exclusion of duplicates and critical review of the full text, 25 articles were included in this systematic review (Figure 1). Of the 25 included articles, 12 were RCTs, seven were prospective observational cohort studies and six were retrospective observational cohort studies. An overview of abstracted data from included studies is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1: Flow Chart of Literature Search.

Table 1: Overview of Abstracted Data from Included Studies.

| Study, Country | Centres (n)/Patients (n) | Study Design, Intervention | Setting/Observation Time | Included | SCV rate n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | |||||

| Falk et al. 1987,[24] US | 1/36 | RCT, oral digoxin versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 18 h observation | New-onset AF seen in the ED or on the wards (duration <7 days) | 17/36 (47.2%) |

| Capucci et al. 1992,[17] Italy | 1/62 | RCT, oral flecainide versus IV amiodaron versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 8 h observation | Recent-onset AF (<7 days) | 10/21 (48%) |

| Capucci et al. 1994,[15] Italy | 1/181 | RCT, oral propafenone versus oral flecainide versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 8 h observation | Recent-onset AF (<7 days) (if AF >72 h only if chronically anticoagulated) | 24/62 (39%) |

| Bellandi et al. 1996,[20] Italy | 1/182 | RCT, IV propafenone versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 24 h observation | Paroxysmal AF lasting >30 min but <7 days | 27/84 (32%) |

| Galve et al. 1996,[21] Spain | 1/100 | RCT, IV amiodaron versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 24 h observation | Recent-onset AF (<7 days) | 30/50 (60%) |

| DAAF trial 1997,[18] Sweden | 13/239 | RCT, IV digoxin versus IV placebo | ED/hospitalised, 16 h observation | Recent-onset AF (<7 days) | 116/239 (48.5%) |

| Azpitarte et al. 1997,[22] Spain | 1/55 | RCT, oral propafenone versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 24 h observation | All patients with acute AF presenting at the ED | 19/26 (73%) |

| Boriani et al. 1997,[16] Italy | 3/240 | RCT, oral propafenone versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 8 h observation | Recent-onset AF (<7 days) (if AF >72 h only if chronically anticoagulated) | 45/121(37.2%) |

| Cotter et al. 1999,[7] Israel | 1/100 | RCT, IV amiodaron versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 24 h observation | Paroxysmal AF <48 h and at least one previous episode of paroxysmal AF | 32/50 (64%) |

| Hohnloser et al. 2004,[14] Germany | 34/201 | RCT, IV tedisamil versus placebo | ED/hospitalised, 2.5 h observation | Symptomatic AF or AFL of 3–48 h duration, BP >90 mmHg systolic and BP <105 mmHg diastolic. | 4/46 (8.7%) |

| Hassan et al. 2007,[23] US | 2/50 | RCT IV diltiazem versus IV esmolol | ED 24h observation (time after drug infusion) | New-onset or paroxysmal AF and a rapid ventricular rate (>100 BPM over 10 min) | 20/50 (40%) |

| Pluymaekers et al. 2019,[8] the Netherlands | 15/437 | RCT, early cardioversion versus wait-and-see | ED 48h observation | Haemodynamic stable, symptomatic patients with AF <36h | 150/218 (69%) |

| Non-RCTs | |||||

| Danias et al. 1998,[3] US | 2/356 | Prospective | ED/hospitalised, observation 4.6 days (time to CV 1.7 days) | AF <72 h | 242/356 (68%) |

| Dell’Orfano et al. 1999,[25] US | 1/114 | Retrospective | ED <48 h observation | Primary diagnosis of AF, documentation of the arrhythmia by single-channel or 12-lead ECG | 57/114 (50%) |

| Mattioli et al. 2000,[28] Italy | 1/140 | Prospective | ED/hospitalised, 48 h observation | Ione AF with a clinically estimated duration of <6 h | 108/140 (77.1%) |

| Mattioli et al. 2005,[27] Italy | 1/116 | Prospective, case control | ED 48 h after onset of symptoms | Haemodynamically stable patients, hospitalised for an acute episode of lone AF (<6 h onset of symptoms) | 72/116 (62.1%) |

| Geleris et al. 2001,[6] Greece | 1/153 | Prospective ED 24 h observation | Consecutive patients with recent onset AF (< 24 h) | 109/153 (71.2%) | |

| Dixon et al. 2005,[26] US | 1/135 | Retrospective | ED/hospitalised, in general monitoring up to 48 h | Primary diagnosis of AF (essential reason for hospital admission) | 71/135 (52.6%) |

| Doyle et al. 2011,[4] Australia | 1/35 | Prospective, wait-and-see | ED 48 h wait-and-see | Patients with stable acute AF <48 h | 22/35 (62.9%) |

| Perrea et al. 2011,[12] Greece | 1/141 | Retrospective pilot study: SCV, amiodaron | ED no observation time | AF at the time of presentation (<48 h) | 28/141 (19.6%) |

| Scheuermeyer et al. 2012,[11] Canada | 2/927 | Retrospective | ED no observation time | Consecutive patients with AF | 121/927 (13.1%) |

| Lindberg et al. 2012,[5] Denmark | 1/374 | Retrospective ED <48 h observation | Consecutive patients admitted to hospital with first onset AF | 203/374 (54%) | |

| Vinson et al. 2012,[13] US | 3/206 | Prospective | ED no observation, small subgroup 48 h wait-and-see | Recent-onset AF (<48 h) | 59/206 (28.6%) 11/16 (68.8%) WAS |

| Choudhary et al. 2013,[19] Sweden | 1/148 | Retrospective | ED SCV <18 h after symptom onset | Patients with paroxysmal AF <48 h | 48/148 (32.4%) |

| Abadie et al. 2019,[29] US | 1/157 | Prospective | ED 30–90 days observation | Low-to-moderate risk AF patient | 48h 98/157 (63%), 30 days 113/136 (83%) |

AFL = atrial flutter; BP = blood pressure; CV = conversion; ED = emergency department; RCT = randomised controlled trial, SCV = spontaneous conversion; WAS = wait-and-see approach.

Quality Assessment

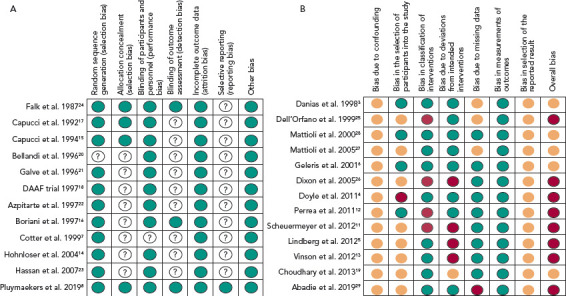

Four of the 12 RCTs were multicentre clinical trials, nine trials compared acute cardioversion with placebo/rate control, two trials compared rate control versus placebo and one trial compared two different rate control strategies. A complete overview of assessment of risk of bias for the RCTs are reported in Figure 2a and Supplementary Material Table 1.

Figure 2: Risk of Bias Assessment.

A: Overview of risk of bias assessment for the randomised controlled trials. Green circles represent a low risk of bias. For white circles with question marks, the risk of bias could not be established. B: Overview of risk of bias assessment for the observational studies. Green circles represent a low risk of bias, orange circles an intermediate risk of bias, red circles a high risk of bias.

An overview of the risk of bias assessment for the observational studies is reported in Figure 2b and Supplementary Material Table 2. Eight studies were assessed to have a serious risk of bias and five a moderate risk of bias.

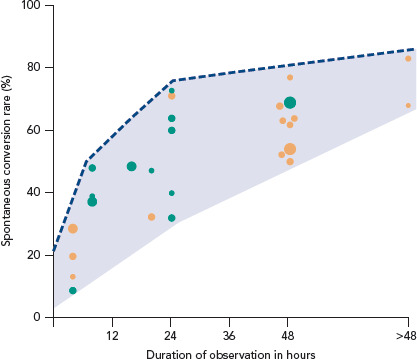

Spontaneous Conversion After a Short Observation Period

Early SCV (<2.5 hours) was described in four studies and conversion rates ranged from 8.7–28.6% (Figure 3).[11–14] The mean age was 64 years and 41% were women. The main difference between the studies was the duration of the onset of symptoms. Perrea et al., Vinson et al. and Hohnloser et al. included only patients with an onset of symptoms <48 hours.[12–14] Scheuermeyer et al. included all patients with AF irrespective of the time of symptom onset.[11] An overview of inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown in Supplementary Material Table 3.

Figure 3: Spontaneous Conversion Rate for Different Periods of Observation Times.

Randomised controlled trials = green; observational studies = orange. The diameter of the circle represents the size of the population included in the trial.

Spontaneous Conversion After a Long Observation Period

Three trials reported a SCV rate at 8 hours ranging from 37–48%. Two were RCTs which compared oral propafenone versus placebo and one trial compared oral flecainide to IV amiodarone and placebo.[15–17] Those trials were comparable regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria and patient characteristics (mean age 58, 58.5 and 60 years; and mean AF duration 28, 30.5 and 35 hours).

A longer observation period of up to 24 hours was described by nine trials and SCV rates varied in those trials from 32–73%.[6,7,18–24] Seven studies were RCTs and two were observational. Baseline characteristics were similar among all these studies, with a mean age of 64 years and on average 47% of patients being women. Notably, inclusion criteria differed with respect to the duration of onset of symptoms at presentation, ranging from <24 hours up to 7 days.

A higher SCV rate (52–77%) was reported in the studies with a long observation period of up to 48 hours (mean age 63 years, 38% women).[4,5,8,13,25–28] In two observational studies the observation period extended beyond 48 hours. Danias et al. reported an SCV rate of 68% after a median observation time of 4.6 days.[3] Abadie et al. reported a SCV rate of 63% at 48 hours and up to 83% after 30 days (Figure 3).[29]

Determinants of Spontaneous Conversion

Determinants of SCV varied among studies (Table 2). Only one study reported on determinants of early SCV, therefore no comparison was made between early and late SCV determinants. Perrea et al. reported a formula ([heart rate/systolic blood pressure] + 0.1 × number of past AF episodes) to determine the likelihood of SCV.[12] Using this formula, a cut-off value of 1.3 was found to have a sensitivity of 78.6% and specificity of 77.9% for predicting SCV.

Table 2: Determinants of Spontaneous Conversion.

| Author, Country | Determinants of SCV |

|---|---|

| Galve et al. 1996,[21] Spain | Absence of congestive heart failure and history of SVT, smaller left atrial size |

| Boriani et al. 1997,[16] Italy | Patients without heart disease (defined as the absence of cardiac abnormalities other than AF)* |

| Cotter et al. 1999,[7] Israel | (Univariable) left atrial size <45 mm, EF >45% and no significant mitral regurgitation |

| Non-RCT | |

| Danias et al. 1998,[3] US | Duration of AF <24 h |

| Dell’Orfano et al. 1999,[25] US | Duration of AF <48 h |

| Mattioli et al. 2000,[28] Italy | Onset AF during sleep, elevated ANP |

| Mattioli et al. 2005,[27] Italy | Patients with acute stress showed the highest probability of SCV followed by patients with Type A behaviour |

| Geleris et al. 2001,[6] Greece | Left atrial dimension (univariable) |

| Perrea et al. 2011,[12] Greece | [HR/systolic blood pressure] + 0.1 × number of past AF episodes |

| Lindberg et al. 2012,[5] Denmark | Duration of AF <48 h |

| Choudhary et al. 2013,[19] Sweden | AFR <350 fpm, presence of IHD and first-ever episode of AF |

*Boriani et al. reported in the same population divided by age, patients with age <60 years as predictor for SCV.35 We excluded studies that did not report on determinants of SCV. AFR = atrial fibrillatory rate; ANP = atrial natriuretic peptide; EF = ejection fraction; fpm = fibrillations per minute; HR = heart rate; IHD = ischaemic heart disease; SCV = spontaneous conversion; SVT = supraventricular tachycardia (previous atrial arrhythmias).

Duration of the AF episode at presentation at the ED appeared to be an important determinant for SCV in three studies. Dell’Orfano et al. and Lindberg et al. reported a higher likelihood of SCV in patients with AF duration <48 hours. Danias et al. reported a higher SCV rate in patients with AF duration <24 hours. Apart from episode duration, first episode of AF, absence of previous supraventricular arrhythmias and normal left atrial dimensions were found to be important determinants of SCV.[6,7,19,21]

Patients without heart failure or underlying heart disease also had a higher SCV rate.[7,16,23] Remarkably, Choudhary et al. reported a higher SCV rate in patients with ischaemic heart disease.[19] Also in this study, a lower AF rate was associated with a higher SCV rate. Mattioli et al. compared personality, socio-economic factors and acute stress in patients with SCV to a matched control group. Patients with acute stress or a type A behaviour pattern had the highest probability of SCV; coffee consumption and a high BMI reduced the SCV rate. Of note, multivariate analyses to determine independent determinants of SCV were not performed in every study and the strategy to include variables in the prediction models varied between studies.

Adverse Events and Thromboembolic Complications

Adverse events were mainly reported in the RCTs and in only two observational studies.[4,7,8,13–18,20–23] An overview of reported adverse events is in Supplementary Material Table 3. Overall adverse events were higher in the cardioversion group compared to the rate control/placebo groups (Supplementary Material Table 4). Reported adverse events in the rate control and placebo group were sustained atrial flutter/tachycardia, pauses >2 seconds and/or bradycardia, vomiting, hypotension and, in one case, heart failure. In the Digitalis in Acute AF (DAAF) trial, one patient in the digoxin group experienced circulatory distress due to previously undiagnosed hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.[18] Hohnloser et al. reported ventricular tachycardia in 2% of cases in the placebo group but no further details were provided.[14] Cotter et al. reported a small non-Q wave MI 24 hours after admission in one patient.[7]

Only six studies (two RCTs and four observational) reported on thromboembolic or bleeding complications, which rarely occurred. Lindberg et al. and Doyle et al. did not observe thromboembolic complications.[4,5] Cotter et al. reported one transient ischaemic attack 10 hours after admission while the patient was in AF.[7] Stroke risk scores, such as CHADS-VASc or CHADS, were not available at the time of this trial and therefore not known for this patient.[30,31] Scheuermeyer et al. reported two strokes within 30 days; a 59-year-old man on rate control medication and known to have a history of diabetes, hypertension and treated with warfarin presented at day 27 with a stroke due to bleeding (international normalised ratio = 4.1).[11] The other was an 82-year-old man, in whom no specific AF treatment was performed and who had a stroke 24 days after visiting the ED. This patient was not on anticoagulant treatment due to a high perceived bleeding risk.

Vinson et al. reported two strokes within 48 hours of the ED visit; neither patient was on anticoagulation therapy. In one patient, anticoagulation was withheld after successful ECV because of previous haemorrhagic complications and one stroke patient underwent rate control during the ED visit but refused anticoagulation treatment.[13] In the Rate Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion Trial 7–Acute Cardioversion Versus Wait and See (RACE 7 ACWAS trial), two patients had cerebral embolism.[8] One occurred 5 days after SCV while on anticoagulation treatment since the previous ED visit, the other stroke occurred 10 days after ECV in a patient who had begun taking anticoagulation treatment during the ED visit.

Discussion

This systematic review provides an overview of the frequency and determinants of SCV of AF in patients presenting at the ED. SCV rates ranged widely between 9–83% depending on the duration of the observation period, and differences in the inclusion and exclusion criteria, such as including first-detected versus all-comers or excluding patients on antiarrhythmic drugs or digoxin. Predictors of SCV also varied between studies. The most important determinants of SCV include short duration of AF (<24 or <48 hours versus longer duration at ED presentation, although that was not supported by all studies), low episode number (first-detected AF versus recurrent AF or previous supraventricular arrhythmias), normal atrial dimensions and absence of previous heart failure or other underlying heart diseases.[3,5,25] Notably, variation between studies concerning predicting factors may also relate to relatively small patient numbers per study and different strategies when including specific variables in the prediction models.

Many patients presenting at the ED with recent-onset AF may convert spontaneously if a sufficiently long observation period is used. The majority of SCVs occur within the first 24–48 hours of observation in patients with relatively short duration of symptoms at the time of presentation. Presumably this finding relates to the intrinsic patientspecific pattern of self-terminating symptomatic AF in patients reporting to the ED, i.e. long enough to cause symptoms and to be still present at the ED, yet self-terminating. This pattern of AF was recently reported as the ‘legato’ (rather than ‘staccato’) type of paroxysmal AF which in the majority of patients lasts hours.[32] Patients with a long legato pattern of a day to a few days of AF are in the minority and responsible for non-spontaneous conversions seen in the ED setting.[3,5,25] From the current data we cannot tell whether patients with ‘early’ SCV have a different risk factor profile or different mechanism of termination compared to patients with ‘late’ SCV.[32] More studies with continuous or intense longitudinal rhythm monitoring are needed to investigate whether those subtypes of recent-onset AF indeed exist and differ in pathophysiology, underlying risk factors, mechanism of termination or even prognosis.

The duration until SCV was assessed variably, some studies taking the symptom onset into account whereas others started measuring from the beginning of the observation period (often from presentation at the ED), all until the time-point of documented SR. This may have contributed to the observed variance in SCV rates. For instance, Mattioli et al. reported a SCV rate of 77% within 48 hours and included only patients with first-onset AF and a symptom onset <6 hours. This stringent selection of patients could explain the higher conversion rate compared to the 52.6% reported by Dixon et al. and 54% reported by Lindberg et al.[5,26] The latter studies included patients with first-onset AF regardless of the duration of AF with the inherent chance to also include a significant subset of patients with longer lasting episodes, in turn responsible for non-conversion even after long observation times up until 48 hours. Whether a more exact documentation of the actual AF duration (e.g. by continuous rhythm monitoring or using the onset of symptoms as a surrogate of AF onset) would reveal a more detailed classification of the AF subtype, and whether this will explain the variance in SCV rates warrants further study.

None of the studies provided data on patient-reported self-termination or on a previously recognised pattern of SCV in those who had experienced SCVs of symptomatic AF in the past. Many patients with recent-onset AF are likely to have experienced previous selftermination and will experience self-termination in the future. Knowing that the pattern may be quite constant, such information could quite robustly guide the choice between early cardioversion and a wait-and-see approach.

The majority of the included studies evaluated SCV during a hospitalised observation period and did not report safety concerns. Only three studies evaluated a wait-and-see approach which included sending patients home while still in AF.[4,8,29] Although those studies were not powered to assess safety, complications were infrequent and similar when compared to active cardioversion.[8] Regardless of the choice of rate or rhythm control for the acute management, early diagnostics and treatment of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular risk factors is an important component of AF management and can help to maintain sinus rhythm and reduce AF burden. A wait-and-see approach may enhance systematic identification of risk factors and concomitant conditions, since it shifts the focus away from acute rhythm control strategies.

A better refinement of determinants of SCV and a categorical classification of patients in different subtypes of recent-onset AF will be crucial to allow a personalised guidance of a wait-and-see approach, which may be a good alternative to acute cardioversion in the management of recent-onset AF. This wait-and-see approach consisting of reassurance and pharmacological rate control at home, reduces the heart rate and complaints of AF, which may improve haemodynamics and enhance atrial electrophysiology and, in turn, enhance conversion to sinus rhythm. Note that in patients with AF >48 hours and considered for an elective cardioversion, SCV can still occur, which can improve characterisation of patients concerning their AF being (non-)selfterminating.[33] This improved patient characterisation can guide personalised future long-term rhythm control therapies such as pill-inthe-pocket therapy or ablation therapy. Besides this, a better identification of patients with (early) SCV can reduce future visits to the ED. Patients can experience that their arrhythmia terminates spontaneously which can improve self-management in case of recurrent episode of AF, and it also reduces overtreatment. During a short-term follow-up of 4 weeks in patients with recent-onset AF, no difference was seen between early cardioversion and a wait-and-see approach in terms of recurrent episodes of AF, time to first recurrence and quality of life. No data is available on the long-term effects and the progression of atrial substrate.

Conclusion

There is a large variation in SCV rate, duration until SCV and determinants of SCV reported in the literature mainly due to differences in duration of the observation period, differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria and different variables used in the prediction models. Future studies are needed to investigate the optimal waiting period in a wait-and-see approach, to define different subtypes of recent-onset AF and to assess the long-term consequences of a wait-and-see approach on the progression of atrial remodelling.

Clinical Perspective

Many patients presenting at the emergency department with recent-onset AF convert spontaneously to sinus rhythm.

Spontaneous conversion (SCV) rates range widely between 9–83%, with higher reported rates with short fibrillation duration, low episode number, normal atrial size, and absence of underlying cardiovascular disease on admission, as well as a longer waiting time until active cardioversion.

Appropriate selection of patients with a high likelihood of early SCV is key to a wait-and-see approach and may help to avoid acute intervention and therefore lower healthcare costs.

Future studies should investigate the optimal waiting time in a wait-and-see approach, evaluate the usefulness of an algorithm for prediction of early conversion incorporating categorical subtypes of recent-onset AF, and assess consequences of a wait-and-see approach for progression of atrial remodelling.

Supplementary file

References

- 1.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893–962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillatio. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e1–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danias P, Caulfield T, Weigner M, Silverman DWM. Likelihood of spontaneous conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:588–92. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00534-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle B, Reeves M. “Wait and see” approach to the emergency department cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation. Emerg Med Int. 2011;2011:545023. doi: 10.1155/2011/545023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindberg S, Hansen S, Nielsen T. Spontaneous conversion of first onset atrial fibrillation. Intern Med J. 2012;42:1195–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geleris P, Stavrati A, Afthonidis H et al. Spontaneous conversion to sinus rhythm of recent (within 24 hours) atrial fibrillation. J Cardiol. 2001;37:103–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotter G, Blatt A, Kaluski E et al. Conversion of recent onset paroxysmal atrial fibrillation to normal sinus rhythm: the effect of no treatment and high-dose amiodarone. A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:1833–42. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pluymaekers NAHA, Dudink EAMP, Luermans JGLM et al. Early or delayed cardioversion in recent-onset atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med. 2019;380:1499–508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Glasgow: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011

- 10.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheuermeyer FX, Grafstein E, Stenstrom R et al. Thirty-day and 1-year outcomes of emergency department patients with atrial fibrillation and no acute underlying medical cause. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:755–65e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perrea DN, Ekmektzoglou KA, Vlachos IS et al. A formula for the stratified selection of patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in the emergency setting: a retrospective pilot study. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinson DR, Hoehn T, Graber DJ, Williams TM. Managing emergency department patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hohnloser SH, Dorian P, Straub M et al. Safety and efficacy of intravenously administered tedisamil for rapid conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capucci A, Boriani G, Botto GL et al. Conversion of recentonset atrial fibrillation by a single oral loading dose of propafenone or flecainide. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:503–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90915-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boriani G, Biffi M, Capucci A et al. Oral propafenone to convert recent-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with and without underlying heart disease. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:621–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capucci A, Lenzi T, Boriani G et al. Effectiveness of loading oral flecainide for converting recent-onset atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm in patients without organic heart disease or with only systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)91392-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Intravenous digoxin in acute atrial fibrillation. Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled multicentre trial in 239 patients. The Digitalis in Acute Atrial Fibrillation (DAAF) Trial Group. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:649–54. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choudhary MB, Holmqvist F, Carlson J et al. Low atrial fibrillatory rate is associated with spontaneous conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2013;15:1445–52. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellandi F, Dabizzi RP, Cantini F et al. Intravenous propafenone: efficacy and safety in the conversion to sinus rhythm of recent onset atrial fibrillation – a single-blind placebocontrolled study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1996;10:153–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00823593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galve E, Rius T, Ballester R et al. Intravenous amiodarone in treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized, controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1079–82. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azpitarte J, Alvarez M, Baun O et al. Value of single oral loading dose of propafenone in converting recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1649–54. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan S, Slim AM, Kamalakannan D et al. Conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm during treatment with intravenous esmolol or diltiazem: a prospective, randomized comparison. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2007;12:227–31. doi: 10.1177/1074248407303792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falk RH, Knowlton AA, Bernard SA et al. Digoxin for converting recent-onset atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. A randomized, double-blinded trial. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:503–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-4-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dell’Orfano JT, Patel H, Wolbrette DL et al. Acute treatment of atrial fibrillation: spontaneous conversion rates and cost of care. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:788–90. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00993-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixon BJ, Bracha Y, Loecke SW et al. Principal atrial fibrillation discharges by the new ACC/AHA/ESC classification. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1877–81. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattioli AV, Bonatti S, Zennaro M, Mattioli G. The relationship between personality, socio-economic factors, acute life stress and the development, spontaneous conversion and recurrences of acute lone atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2005;7:211–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattioli AV, Vivoli D, Borella P, Mattioli G. Clinical, echocardiographic, and hormonal factors influencing spontaneous conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:351–2. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)00933-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abadie BQ, Hansen B, Walker J et al. Likelihood of spontaneous cardioversion of atrial fibrillation using a conservative management strategy among patients presenting to the emergency department. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:1534–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gage BF, Walraven Cv, Pearce L et al. Selecting patients with atrial fibrillation for anticoagulation. Circulation. 2004;110:2287–92. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145172.55640.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wineinger NE, Barrett PM, Zhang Y et al. Identification of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation subtypes in over 13,000 individuals. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein AL, Grimm RA, Murray RD et al. Use of transesophageal echocardiography to guide cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1411–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boriani G, Biffi M, Capucci A et al. Oral loading with propafenone: a placebo-controlled study in elderly and nonelderly patients with recent onset atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:2465–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1998.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.