Abstract

Alternative splicing (AS) leads to transcriptome diversity in eukaryotic cells and is one of the key regulators driving cellular differentiation. Although AS is of crucial importance for normal hematopoiesis and hematopoietic malignancies, its role in early hematopoietic development is still largely unknown. Here, by using high‐throughput transcriptomic analyses, we show that pervasive and dynamic AS takes place during hematopoietic development of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). We identify a splicing factor switch that occurs during the differentiation of mesodermal cells to endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). Perturbation of this switch selectively impairs the emergence of EPCs and hemogenic endothelial progenitor cells (HEPs). Mechanistically, an EPC‐induced alternative spliced isoform of NUMB dictates EPC specification by controlling NOTCH signaling. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the splicing factor SRSF2 regulates splicing of the EPC‐induced NUMB isoform, and the SRSF2‐NUMB‐NOTCH splicing axis regulates EPC generation. The identification of this splicing factor switch provides a new molecular mechanism to control cell fate and lineage specification.

Keywords: alternative splicing, NOTCH signaling, NUMB, splicing factor switch, SRSF2

Subject Categories: Chromatin, Epigenetics, Genomics & Functional Genomics; Haematology; Regenerative Medicine

Alternative splicing leads to transcriptome diversity and drives cellular differentiation. During hematopoietic stem cell differentiation, a splicing factor switch reshapes the transcriptome, thereby instructing the generation of endothelial progenitors.

Introduction

Alternative splicing (AS) is a pervasive post‐transcriptional process in eukaryotes, occurring in approximately 92–94% of human multi‐exon genes (Wang et al, 2008). AS of pre‐mRNA generates multiple isoforms that robustly amplify the complexity and flexibility of the genome and considerably enhance the diversity of transcriptomes. Distinct splicing isoforms produce functionally equivalent or divergent proteins (Baralle & Giudice, 2017) that are often expressed in a tight spatial/temporal manner and execute diverse physiological roles to modulate lineage differentiation and organismal development (Barbosa‐Morais et al, 2012; Yang et al, 2016). As ~ 15% of disease‐causing mutations are located within splice sites and greater than 20% of missense mutations lie within predicted splicing elements (Singh & Cooper, 2012), splicing aberrations cause or contribute to a variety of diseases.

The hematopoietic system is a particularly instructive model for delineating AS. AS has been characterized in hematopoietic stem cells generation (HSCs; Chen et al, 2014; Goldstein et al, 2017), erythropoiesis (Pimentel et al, 2014; Edwards et al, 2016), granulopoiesis (Wong et al, 2013), megakaryopoiesis (Edwards et al, 2016), and monocyte‐to‐macrophage differentiation (Liu et al, 2018a). During erythroid (Pimentel et al, 2016) and granulocytic maturation (Wong et al, 2013), intron retention controls differentiation by sequestering transcripts with retained introns in the nucleus, which regulates the timing of protein translation. In addition, alternatively spliced protein isoforms have been reported to have lineage‐ and differentiation‐stage‐specific roles in hematopoiesis. Ikaros (IKZF1) is a key transcription factor that regulates lymphopoiesis and myelopoiesis (Yoshida et al, 2006). Its major isoform, Ikaros‐1, is required for lymphoid and erythroid cell fate decisions (Yoshida et al, 2006), whereas its minor isoform, Ikaros‐X, is expressed predominantly in granulocytes and monocytes (Payne et al, 2003). In addition, distinct Lamin B1 (Wong et al, 2013) and NFIB isoforms (Chen et al, 2014) uniquely influence granulocytic and megakaryocytic differentiation, respectively. Furthermore, AS of MDM4 (Yu et al, 2019), RUNX1 (Komeno et al, 2014), and HMGA2 (Cesana et al, 2018) regulates HSC maintenance, homeostasis, and developmental stage‐specific transcriptional programs, respectively. Mutations of genes encoding core spliceosome proteins and auxiliary regulatory splicing factors, such as SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2, are frequently detected in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome, leukemia, and clonal hematopoiesis (Yoshida et al, 2011; Saez et al, 2017; Sperling et al, 2017; Hodson et al, 2019). Although AS has important physiological and pathological functions in hematopoiesis, the extent of its involvement in regulating embryonic hematopoiesis is largely unclear.

During ontogeny, hematopoietic cells originate from the lateral plate mesoderm and lateral plate mesoderm differentiate into hemogenic endothelial (HE) cells, which undergo endothelial‐to‐hematopoietic transition (EHT) and subsequently generate hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Transcription factors, such as RUNX1 (Lacaud et al, 2002; Chen et al, 2009; Gao et al, 2018), GATA2 (Johnson et al, 2012; Lim et al, 2012; de Pater et al, 2013; Gao et al, 2013; Kang et al, 2018; Zhou et al, 2019), SCL/TAL1 (Porcher et al, 2017), GFI1 and GFI1B (Thambyrajah et al, 2016), MEIS2 (Wang et al, 2018b), and MEIS1 (Wang et al, 2018a), orchestrate hematopoietic development. Studies in zebrafish have demonstrated that spliceosomal mutants (sf3b1 (De La Garza et al, 2016), u2af1 (Danilova et al, 2010), prpf8 (Keightley et al, 2013)) greatly impair hematopoietic development. However, many questions remain unanswered regarding the role of AS in human hematopoietic development. An exception is RUNX1, which is essential for EHT (North et al, 1999; Lacaud et al, 2002; Chen et al, 2009; Lancrin et al, 2009; Kissa & Herbomel, 2010). An alternative isoform of RUNX1a increases hematopoietic differentiation and multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution in a transplantation model when overexpressed in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) (Challen & Goodell, 2010; Ran et al, 2013; Lie et al, 2018).

In this study, we established the AS profile during human embryonic stem cell (hESC)‐based hematopoietic differentiation. These analyses revealed a splicing factor switch that occurs during endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) generation. The disruption of splicing severely blocked the splicing factor switch and selectively attenuated the emergence of EPCs and hemogenic endothelial progenitor cells (HEPs), while having little impact on the production of mesoderm cells or HSPCs. Mechanistically, an EPC‐induced NUMB isoform was markedly downregulated with the perturbation of the splicing pattern, which altered NOTCH signaling. Finally, we provide evidence for a SRSF2‐NUMB‐NOTCH axis that controls EPC specification.

Results

Dynamic alternative splicing program of human hematopoietic development from ESCs

The differentiation of hESCs to hematopoietic cells occurs in a sequential manner (Wang et al, 2018a; Wang et al, 2018b; Wang et al, 2020). This process involves exit from a pluripotent state and generation of lateral plate mesoderm cells (APLNR+) at day 2. APLNR+ cells are capable of differentiating into the hematopoietic lineage (Choi et al, 2012). At day 5, CD31+CD34+ endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) (Ramos‐Mejia et al, 2014; Xie et al, 2015) and CD31+CD34+CD73− hemogenic endothelial progenitor cells (HEPs) (Ditadi et al, 2015) are formed from APLNR+ cells, and CD43+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are generated by day 8 (Fig 1A). To determine the kinetics of transcriptome remodeling during hematopoietic development, we conducted RNA sequencing (RNA‐Seq) with hESCs, FACS‐purified APLNR+ mesoderm cells, CD31+CD34+ EPCs, and CD43+ HSPCs at various differentiation stages (Figs 1A and EV1A). This analysis yielded an average of 88 million unique reads per sample, which was sufficient to detect low‐abundant transcripts and low‐frequency AS events.

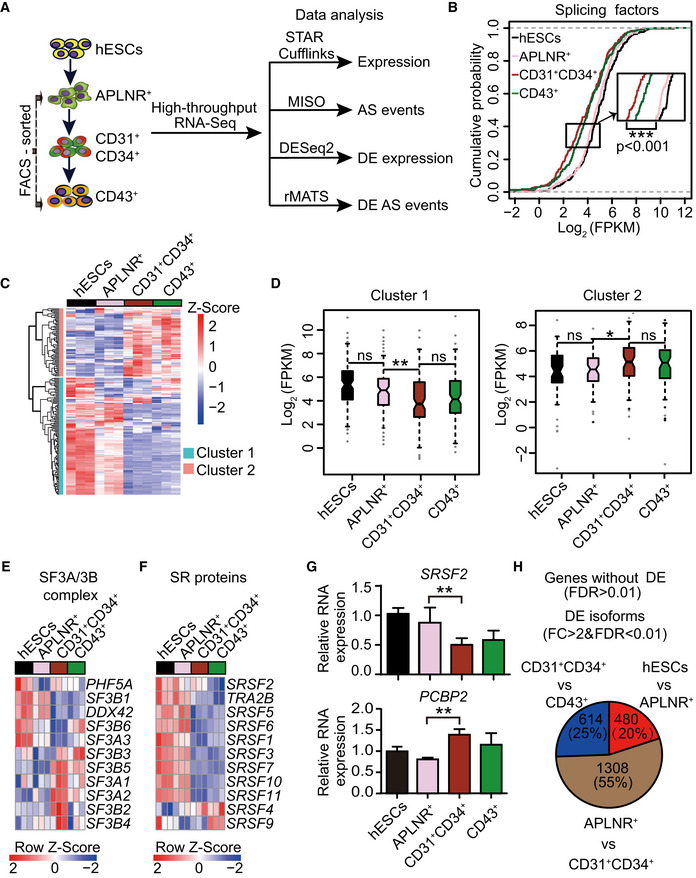

Figure 1. The dynamic alternative splicing program during hESC hematopoietic differentiation.

-

ASchematic representation of the strategies for fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) and transcriptomic analyses. During hematopoietic differentiation, human embryonic stem cells (hESCs, H1) on day 0, FACS‐purified lateral plate mesodermal APLNR+ cells on day 2, purified CD31+CD34+ endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) on day 5, and purified CD43+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) on day 8 were collected for RNA‐Seq, respectively. STAR Cufflinks, MISO, DESeq2, and rMATS were used to analyze the expression abundance of genes and transcripts, alternative splicing events, differentially expressed genes and transcripts, and differential splicing events, respectively. n = 3 technical replicates.

-

BCumulative distribution curves of Log2(FPKM) of splicing factors (n = 235) in hESCs APLNR+, CD31+CD34+, and CD43+ cells. The upper and lower dotted lines represent cumulative scores of 1 and 0, respectively. n = 3 technical replicates. The P‐value was calculated by a two‐tailed Wilcoxon signed‐rank test.

-

CThe heatmap illustrates the expression scaled by row of components within the major spliceosomal machinery (n = 182) using unsupervised hierarchical clustering. The heatmap was scaled with Z‐Score using the log2(FPKM) expression of components within the major spliceosomal machinery. n = 3 technical replicates.

-

DThe boxplots depict the expression of splicing factors in cluster 1 (n = 115) and cluster 2 (n = 67) identified in (C) at distinct differentiation stages. The central band indicates the median level of expression. Boxes present 25%‐75% of genes expression. The whiskers indicate the lowest and highest points within 1.5 × the interquartile. n = 3 technical replicates. P‐values were calculated by a two‐tailed Wilcoxon signed‐rank test.

-

E, FThe heatmap shows the dynamic expression of genes in the SF3A/3B complex (E) and SR family (F) at each indicated differentiation stage. Both heatmaps were scaled by row. The heatmaps were scaled with Z‐Score using the log2(FPKM) expression of indicated components. n = 3 technical replicates.

-

GThe mRNA expression of splicing regulator SRSF2 and splicing factor PCBP2 during hematopoietic differentiation was measured by RT–qPCR. The ACTB gene was used as a control. Results given are mean ± standard deviation (SD). P‐values were determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. n ≥ 3 biological replicates.

-

HThe number of differentially expressed transcripts at the isoform level (fold change (FC) > 2 & FDR < 0.01), but not at the gene level (FDR > 0.01), by comparing two consecutive differentiation stages (hESC vs APLNR+ cells, APLNR+ cells vs CD31+CD34+ cells, and CD31+CD34+ cells vs CD43+ cells).

Data information: * presents P < 0.05. ** presents P < 0.01. *** presents P < 0.001.

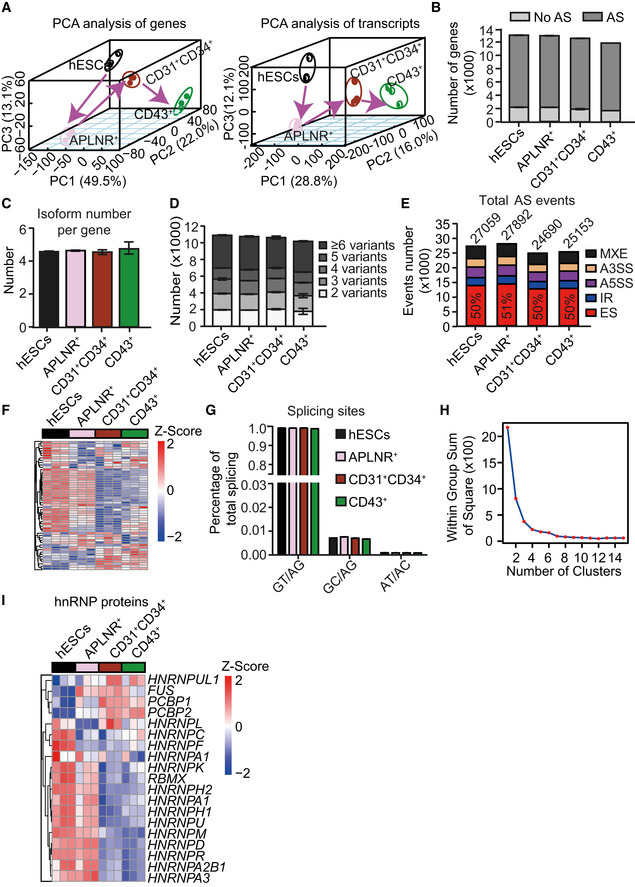

Figure EV1. Pervasive and dynamic alternative splicing occurs during human hematopoietic differentiation induced from hESCs.

- Principal component analysis (PCA) of genes (left) and transcripts (right) in highly purified cells at various differentiation stages, including ESCs, APLNR+ cells, CD31+CD34+ cells, and CD43+ cells during hematopoietic differentiation induction from hESCs.

- Widespread occurrence (> 85% of expressed genes) of alternative splicing in expressed genes (FPKM> 1 in at least one differentiation stage) at distinct differentiation stages during hematopoietic development.

- Average number of isoforms per gene at each differentiation stage.

- Analysis of isoform variants within each expressing gene at distinct differentiation stages.

- Number and frequency of five major splicing events at distinct differentiation stages, including mutually exclusive exon (MXE), alternative 5′ splicing (A5SS), alternative 3′ splicing (A3SS), intron retention (IR), and exon skipping (ES). The cutoff of splicing event of an expressed gene is 0.05 < PSI < 0.95.

- Heatmap showing the genes within the minor spliceosomal machinery (n = 52) at the indicated stages. The heatmap was row normalized. The heatmap was scaled with Z‐Score using the log2(FPKM) expression of indicated components within the minor spliceosomal machinery.

- Frequency of splicing site at different differentiation stages.

- The elbow plot assessing the potential clusters of the dynamic splicing factors expression in the heatmap of Fig 1 (C).

- Heatmap showing the genes in the hnRNP family at the indicated stages. The heatmap was row normalized. The heatmap was scaled with Z‐Score using the log2(FPKM) expression of indicated genes..

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD.For all panels n = 3 technical replicates.

We selected genes with expression level > 1 fragment per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM) in at least one differentiation stage for all RNA‐Seq analysis. This analysis revealed widespread AS (> 85% of expressed genes) during hematopoietic development (Fig EV1B). Each expressed gene had an average of 4.6 isoforms (Fig EV1C), and ~ 36% of them possessed > 6 isoforms (Fig EV1D) during differentiation. To dissect splicing patterns underlying the isoform diversity, we analyzed the frequency of five major splicing events: the mutually exclusive exons (MXE), alternative 5′ splicing site (A5SS), alternative 3′ splicing site (A3SS), intron retention (IR), and exon skipping (ES) (Fig EV1E). ES was the most prevalent, which comprised approximately half (mean ~ 50 ± 1%) of the splicing events detected (Fig EV1E). While the overall frequency of splicing events decreased when APLNR+ cells differentiated into EPCs (27,892 vs. 24,690; Fig EV1E), the proportion of each splicing event remained relatively constant throughout differentiation (Fig EV1E). Thus, a robust AS program occurs during human hematopoietic development.

A splicing factor switch occurs during EPC generation

Appropriate splicing requires the tight regulation of the spliceosome, a mega‐dalton complex consisting of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins and hundreds of auxiliary proteins known as splicing factors (Jurica & Moore, 2003). There are two types of splicing machines: the major and minor spliceosome. The major spliceosome utilizes the more common U2 splice site (GU‐AG) and accounts for most of the splicing events, while the minor spliceosome is used to splice the less frequent U12‐type “minor” introns (AU‐AC) (Sharp & Burge, 1997).

To illustrate the dynamic expression of spliceosome components during hematopoietic differentiation, we plotted the expression of all expressed splicing factors at distinct differentiation stages (Fig 1B and Dataset EV1). We found that splicing factor expression levels were reduced significantly during the differentiation of APLNR+ mesoderm cells to EPCs (Fig 1B and Dataset EV1). In contrast, their expression remained constant during the transition from hESCs to APLNR+ cells and from EPCs to HSPCs (Fig 1B and Dataset EV1).

We analyzed the expression of splicing factors at the level of individual genes. Analysis of heatmaps illustrating every expressed component of the major and minor spliceosome revealed a splicing factor switch in both major and minor spliceosomes during the mesoderm to EPC transition (Figs 1C and EV1F). Because the major spliceosome is responsible for > 99% of the splicing events during hematopoietic development (Fig EV1G), we focused on it hereafter. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering segregated the splicing factors of the major spliceosome into two primary clusters (Fig 1C), in accord with the elbow analysis (Fig EV1H), a method to calculate and propose the optimal number of clusters (Bholowalia & Kumar, 2014). Splicing factors in cluster 1 (n = 115, ~70%) were downregulated significantly (median level: 36.4–18.2, P = 0.002) during the production of EPCs from APLNR+ cells. In contrast, those in cluster 2 (n = 67, ~30%) were upregulated significantly (median level: 23.6–35, P = 0.02) (Fig 1D).

We analyzed expression of the constitutive components in each splicing subcomplex (e.g., SF3A/B and U2AF) and the key splicing regulators, including the SR proteins that contain a domain with serine/arginine repeats and hnRNPs. There was a switch in expression of the family members within the specific splicing subcomplex during the production of EPCs from mesoderm cells (Figs 1E and F, and EV1I). In the SF3A/B subcomplex, SF3B1 expression decreased rapidly, while other components, including SF3B2, SF3B3, SF3B4, and SF3B5, were upregulated (Fig 1E). A similar switch occurred for the SR proteins and hnRNPs during EPC generation (Figs 1F and EV1I). RT–qPCR analysis verified the dynamic expression pattern of individual genes, including SRSF2 and PCBP2 (Fig 1G).

Concomitant with the splicing factor switch, the highest frequency of transcripts differentially expressed at the isoform, but not the gene, level was detected during mesoderm to EPC transition. We identified 1,308 differentially expressed isoforms during the conversion of APLNR+ cells to EPCs in comparison with 480 during hESC differentiation to APLNR+ cells and 614 from EPCs to HSPCs (Fig 1H). In summary, these results reveal that splicing factor expression is tightly controlled during hematopoietic differentiation.

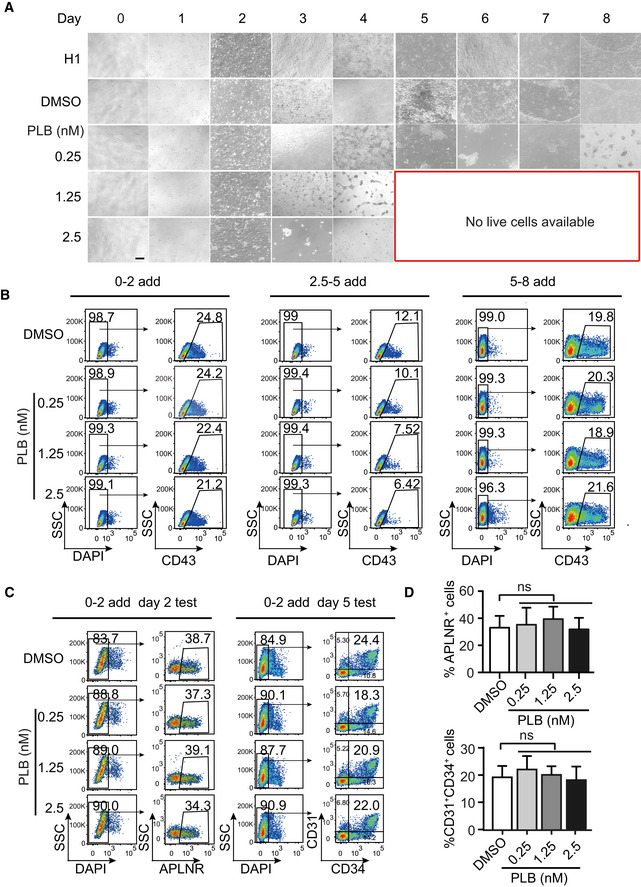

Inhibition of splicing selectively disrupts the generation of EPCs and HEPs

To unveil the function of splicing in hematopoietic development, we treated the cells with pladienolide B (PLB), a natural product that inhibits the spliceosome by targeting SF3B1 (Kotake et al, 2007). However, the administration of PLB throughout the entire hematopoietic differentiation process, even at a low dose (0.25 nM), was cytotoxic and induced cell death (Fig EV2A). Thus, we added PLB in a stage‐specific manner using a wide range of doses (Fig 2A).

Figure EV2. Effects of long and short PLB treatment on hematopoietic differentiation.

- The morphological alterations of cells treated without (DMSO control) or with various amount of PLB throughout the hematopoietic differentiation. Scale bar = 20 μm.

- Representative FACS plots illustrating the CD43+ HSPCs without or with PLB treatment at the indicated concentrations and treatment periods.

- Representative FACS plots showing the frequency of APLNR+ cells on day 2 of differentiation and CD31+CD34+ EPCs on day 5 without or with PLB treatment from day 0 to 2 at the indicated concentrations.

- The bar graph showing the percentage of APLNR+ cells and CD31+CD34+ EPCs of (C). Results given are mean ± SD. P‐values were calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. ns represents no significant difference. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates.

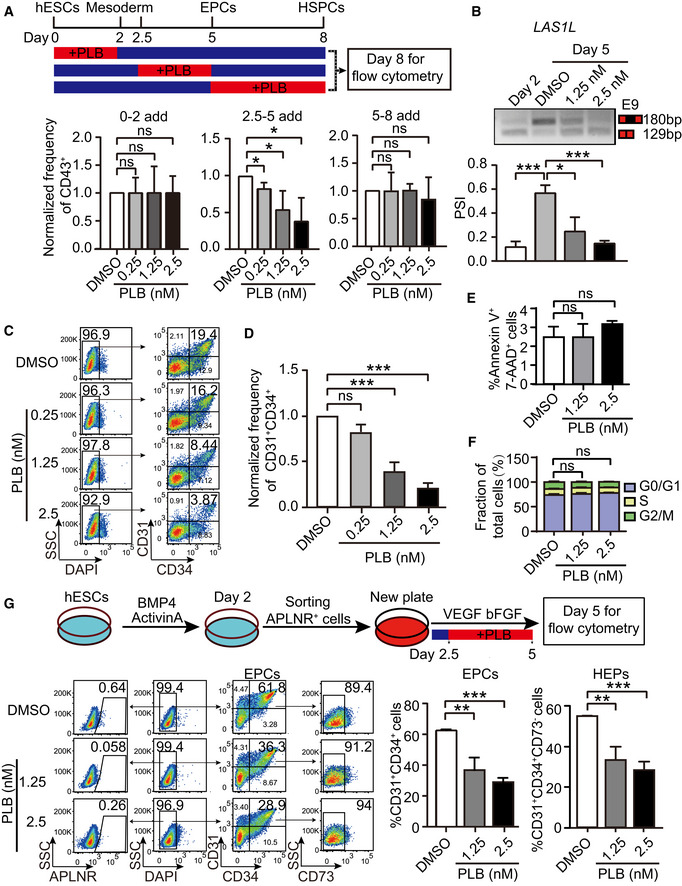

Figure 2. Inhibition of splicing disrupts EPC and HEP generation.

- The upper schematic illustrates the stage‐specific supplementation of splicing inhibitor PLB and on day 8 CD43+ HSPCs were examined by flow cytometry. The bottom bar graph showing the normalized frequency of CD43+ cells to DMSO control under distinct PLB treatment windows. P‐values were calculated by one‐way followed by Dunnett’s test.

- The top panel is a representative RT–PCR electropherogram depicting the inclusion or exclusion LAS1L exon 9 in cells at day 2 as well as cells at day 5 without or with PLB treatment with indicated concentrations, respectively. The quantification of percent spliced‐in (PSI) was presented in the bottom bar graph. P‐values were calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test.

- The representative FACS plots show the generation of CD31+CD34+ EPCs at day 5 of differentiation upon PLB treatment from day 2.5 to 5.

- The frequency of CD31+CD34+ EPCs with PLB treatment in (C) was normalized to DMSO control. P‐values were calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test.

- Cell apoptotic level assessed using Annexin V and 7‐AAD at day 5 of differentiation by flow cytometry. The cells were treated with or without PLB from day 2.5 to 5.

- The proportion of G0/G1, S, and G2/M cells at day 5 of differentiation treated with or without PLB from day 2.5 to 5. The cell cycle was determined by flow cytometry with propidium iodide staining.

- The experimental schematic (upper panel). APLNR+ cells on day 2 were FACS‐purified and treated with various dosages of PLB from day 2.5 to 5 during hematopoietic differentiation. On day 5, the generation of CD31+CD34+ EPCs and CD31+CD34+CD73− HEPs was assessed. The representative FACS plots showed the frequency of APLNR+ cells, CD31+CD34+ EPCs, and CD31+CD34+CD73− HEPs without or with PLB treatment. The bar graphs show the percentage of CD31+CD34+ EPCs and CD31+CD34+CD73− HEPs without or with PLB treatment.

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD. P‐values were determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test in (E), (F), and (G). ns represents no significant difference, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates.

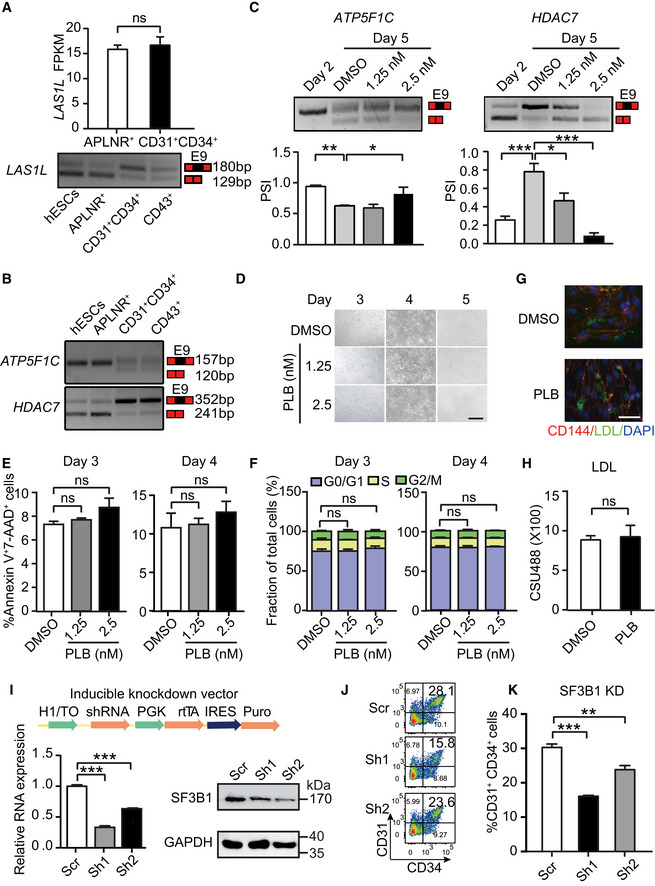

Consistent with the bioinformatics analysis demonstrating the splicing factor switch during the mesoderm to EPC transition, the addition of PLB from day 2.5 to 5 diminished the output of CD43+ HSPCs (Figs 2A and EV2B). Conversely, inhibition of splicing with PLB from day 0 to 2 or from day 5 to 8 did not influence HSPC generation (Figs 2A and EV2B). We did not detect significant defects in mesodermal APLNR+ cell specification and EPC generation during the treatment from day 0 to 2 (Fig EV2C and D). In addition, the impact of PLB on splicing was confirmed by RT–PCR using genes exhibiting alternative isoform usage during the conversion of APLNR+ cells to EPCs, such as LAS1L, ATP5F1C, and HDAC7 (Figs 2B and EV3A–C).

Figure EV3. Short PLB treatment exhibits minor cytotoxic effects.

- Expression of LAS1L in day 2‐differentiated APLNR+ cells and day 5‐differentiated CD31+CD34+ cells by RNA‐Seq. The bottom panel showing the inclusion/exclusion of LAS1L exon 9 during hematopoietic differentiation by RT–PCR.

- The inclusion/exclusion of exon 9 of ATP5F1C and HDAC7 detecting by RT–PCR during hematopoietic differentiation.

- The top panel is a representative RT–PCR electropherogram showing the inclusion or exclusion of exon 9 in ATP5F1C (left) and HDAC7 (right) in cells at days 2 and 5 without or with PLB treatment at indicated concentrations, respectively. The quantification of PSI is presented in the bottom bar graph. P‐values were calculated by one‐way followed by Dunnett’s test.

- The cellular morphology on days 3, 4, and 5 during hematopoietic differentiation after treatment with 1.25 or 2.5 nM PLB from day 2.5 to 5. Scale bar = 40 μm.

- Cellular apoptosis assessed using Annexin V and 7‐AAD at days 3 and 4 of differentiation by flow cytometry, with or without PLB treatment from day 2.5 to 5.

- The proportion of G0/G1, S, and G2/M cells at days 3 and 4 of differentiation, with or without PLB treatment from day 2.5 to 5, respectively. The cell cycle was determined using propidium iodide staining by flow cytometry.

- Immunofluorescent staining depicting low‐density lipoprotein (AcLDL) uptake from FACS‐sorted CD31+ cells without (DMSO) or with PLB (1.25 nM) treatment. CD144, LDL, and DAPI were stained (upper) by red, green, and blue, respectively. Scale bar = 40 μm.

- The bar graph showing the quantification of the LDL fluorescent intensity by the Volocity 3D image analysis software.

- The schematic illustrating the DOX‐inducible knockdown system with expression of SF3B1 shRNAs. The knockdown of SF3B1 was confirmed by RT–qPCR (left) and Western blotting (right) after inducing with DOX.

- The representative FACS plots of CD31+CD34+ EPCs after SF3B1 depletion at day 5 of differentiation.

- The percentage of CD31+CD34+ EPCs after SF3B1 depletion at day 5 of differentiation.

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD. P‐values were determined by Student’s t‐test in (A), (E), (F), (H), (I), and (K). ns represents no significant difference. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Pladienolide B treatment from day 2.5 to 5 inhibited EPC specification in a dose‐dependent manner. At 2.5 nM, EPC specification was reduced by about 5‐fold (mean 18.8 vs. 4.4%, P < 0.001, Fig 2C and D). The reduced EPC production did not reflect increased apoptosis or decreased proliferation (Figs 2E and F, and EV3D–F). Low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake assay in EPCs demonstrated no apparent difference in LDL uptake capacity, suggesting maintenance of normal cellular function of EPCs (Fig EV3G and H). Thus, inhibition of splicing impairs EPC production, independent of apoptosis or proliferation.

Since PLB inhibits splicing via targeting splicing factor SF3B1, we used a shRNA‐based genetic approach to reduce SF3B1 expression (Fig EV3I). Using a doxycycline (DOX)‐inducible knockdown system, reducing SF3B1 expression during hematopoietic differentiation (1 μg/ml DOX treatment from day 2.5 to 5) decreased generation of CD31+CD34+ EPCs, recapitulating the inhibitory effect of PLB (Fig EV3J and K).

We tested whether the reduced generation of EPCs results from impaired differentiation potential of APLNR+ cells. We sorted day 2‐differentiated APLNR+ cells and induced hematopoietic differentiation, with or without PLB treatment, from day 2.5 to 5 (Fig 2G). Generation of EPCs decreased from 61.5 to 28.7% at 2.5 nM PLB treatment (P < 0.001, Fig 2G). The generation of CD31+CD34+CD73− HEPs also decreased in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig 2G). Since APLNR+ cells were barely detectable at day 5 of differentiation, the decreased generation of EPCs and HEPs likely reflected the defective production of EPCs from APLNR+ cells upon splicing inhibition (Fig 2G).

Thus, inhibition of splicing reduces the generation of EPCs and HEPs, but not APLNR+ cells or HSPCs, suggesting that the generation of EPCs and HEPs is most susceptible to the splicing defects.

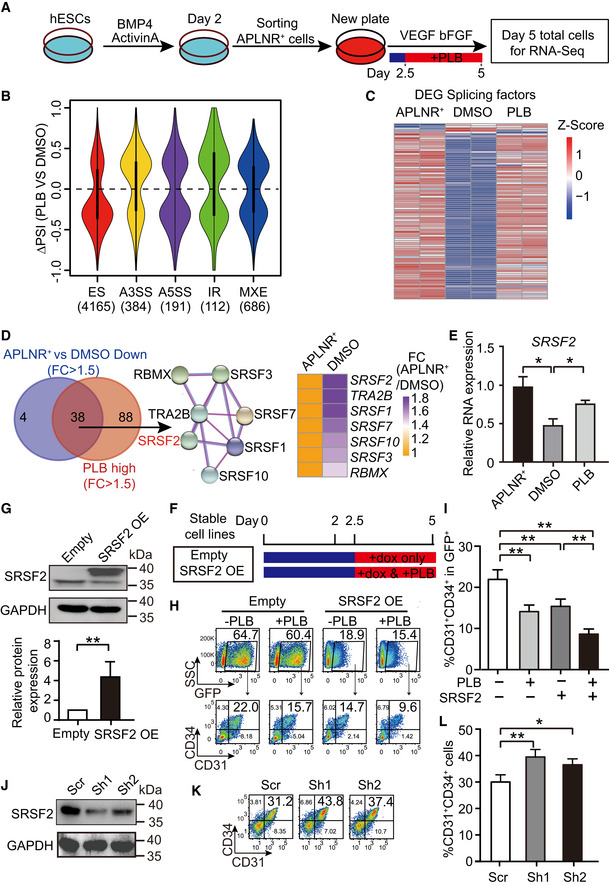

Disruption of the splicing factor switch inhibits EPC and HEP specification

We evaluated the potential link between the splicing factor switch and impaired EPC generation. To this end, APLNR+ cells at day 2 were sorted and hematopoietic differentiation was induced, with or without PLB (2.5 nM) from day 2.5 to 5. The day 2‐APLNR+ cells, day 5‐DMSO‐treated cells, and day 5‐PLB‐treated cells were harvested, and RNA‐Seq was conducted (Fig 3A). To confirm whether PLB treatment perturbs splicing events and leads to the alterations in splicing subtypes, we analyzed the differential splicing events with genes FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage and delta percent spliced‐in (PSI) > 0.2 and FDR < 0.05 (Figs 3B and EV4A). We found an aberrant splicing pattern induced by PLB was similar to that described in myeloid cells with SF3B1 mutant (Sf3b1 +/K700E) (Obeng et al, 2016), including an increased frequency of A3SS (Fig 3B).

Figure 3. Disruption of the splicing factor switch impacts EPC specification.

- The schematic depicting experimental strategy for RNA‐Seq. APLNR+ cells on day 2 were FACS‐purified and treated with 1.25 nM or 2.5 nM PLB from day 2.5 to 5 during hematopoietic differentiation. Then, the day 2‐purified APLNR+ cells, day 5‐differentiated cells with or without PLB treatment were harvested for RNA‐Seq. n = 2 technical replicates.

- The violin plot represents distributions of statistically significant ΔPSI for different types of splicing events by comparison of PLB‐treated cells vs DMSO control. The number of differential splicing events regulated by 2.5 nM PLB is denoted in brackets. we analyzed the differential splicing events with genes FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage. Among them, the cutoffs of PSI > 0.2 and FDR < 0.05 were used to define differential splicing events. The dotted line indicates ΔPSI = 0.

- The heatmap shows the expression of differentially expressed splicing factors in APLNR+ cells, day 5‐differentiated cells treated with DMSO or 2.5 nM PLB. The differentially expressed splicing factors were defined as fold change of FPKM > 1.5 between APLNR+ cells and DMSO‐treated cells. The heatmap was scaled with Z‐Score using the log2(FPKM) expression of differentially expressed splicing factors. n = 2 technical replicates.

- The Venn diagram presents the intersection between highly expressed genes in APLNR+ cells (APLNR+ cells vs. DMSO‐treated cells; FC > 1.5) and highly expressed genes in PLB on day 5 (PLB‐treated cells vs DMSO; FC > 1.5). The STRING diagram (middle) shows the protein interaction networks among the 38 candidates. The heatmap on the right illustrates the fold change of 7 splicing regulators between APLNR+ and DMSO‐treated cells.

- RT–qPCR showing the mRNA level of SRSF2 in APLNR+ cells and day 5‐differentiated cells without or with 2.5 nM PLB treatment. The SRSF2 expression was normalized to that in APLNR+ cells. The ACTB gene was used as a control. P‐values were determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test.

- Schematic of experimental design. During hematopoietic differentiation, stable cell lines harboring SRSF2 expression vector and its corresponding empty vector control were treated with DOX alone or in combination with 1.25 nM PLB from day 2.5 to 5. The cells were harvested for analysis on day 5 of differentiation.

- The Western blotting illustrates the overexpression of SRSF2 in sorted GFP+ cells on day 5 during differentiation, which were induced with DOX from day 2.5 to 5. GAPDH was used as the loading control. The bar graph presents the quantification of SRSF2 protein expression. The P‐value was determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test.

- The representative FACS plots show the frequency of CD31+CD34+ EPCs in the GFP+ population at day 5 with 1.25 nM PLB supplementation or SRSF2 exogenous expression alone or their combinational treatment from day 2.5, as described in (G).

- The bar graph represents the percentage of CD31+CD34+ cells from (H). P‐values were calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

- The Western blotting shows the depletion of SRSF2 in the DOX‐inducible knockdown system. GAPDH acts as the loading control.

- The representative FACS plots show the frequency of CD31+CD34+ EPCs at day 5 with or without SRSF2 depletion by administration of DOX from day 2.5 to 5.

- The bar graph representing the percentage of CD31+CD34+ cells from (K). P‐values were determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test.

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates unless stated otherwise.

Source data are available online for this figure.

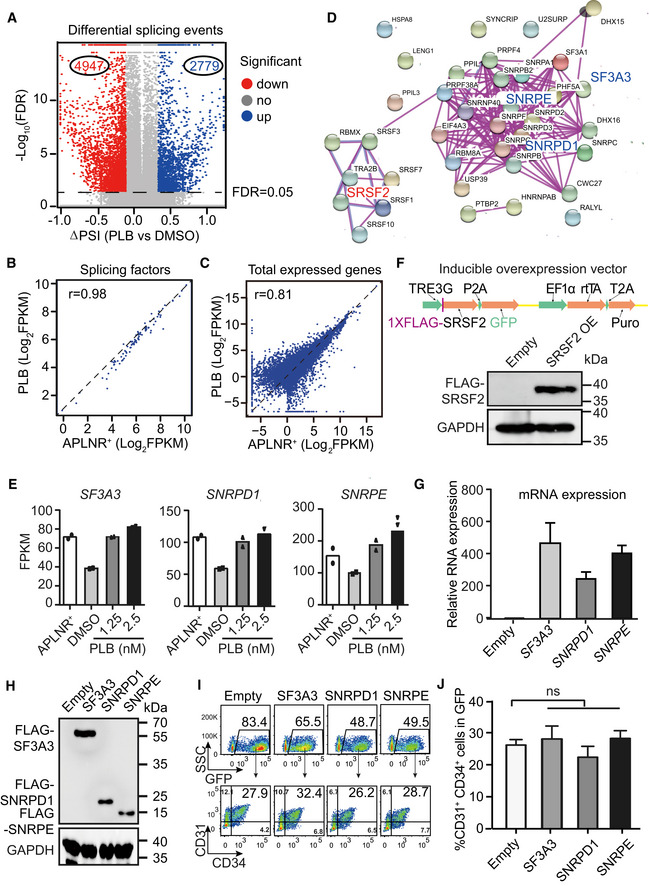

Figure EV4. Effects of ectopic expression of constitutive splicing factors on human hematopoietic differentiation.

-

AVolcano plot shows the differential splicing events regulated by PLB treated from day 2.5 to 5. The dotted line denotes FDR = 0.05.

-

B, CThe scatter plot showing the correlation of splicing factors form Fig 3c (B) and all expressed genes (C) between day 2‐APLNR+ cells and day 5‐PLB‐treated cells. r refers to the correlation coefficient.

-

DThe protein–protein interaction network of 38 intersected splicing factors (Fig 3D) (STRING: https://string‐db.org/).

-

EThe mRNA expression of SF3A3, SNRPD1, and SNRPE in day 2‐APLNR+ cells, day 5‐DMSO–treated, and day 5‐PLB‐treated cells. N = 2 technical replicates.

-

FThe upper panel illustrates the DOX‐inducible overexpression system. Western blotting confirmed the SRSF2 overexpression upon DOX induction with anti‐FLAG antibody. GAPDH was used as the loading control.

-

GRT–qPCR assay of the relative mRNA expression of SF3A3, SNRPD1, and SNRPE after overexpression upon DOX induction. The ACTB gene was used as a control. Data were normalized to the mRNA level of empty vector controls cells.

-

HWestern blotting showing the protein expression of SF3A3, SNRPD1, and SNRPE after overexpression with anti‐FLAG antibody. The GAPDH gene was used as a control.

-

IRepresentative FACS plots of CD31+CD34+ cells in SF3A3, SNRPD1, and SNRPE overexpressed (GFP+) cells.

-

JStatistical analysis of the frequency of CD31+CD34+ in SF3A3, SNRPD1, and SNRPE overexpressed (GFP+) cells.

Data information: P‐values were calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. ns represents no significant difference. Results given are mean ± SD.. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates unless stated otherwise

Source data are available online for this figure.

Interestingly, PLB administration blocked the splicing factor switch and altered the expression pattern to closely resemble that of APLNR+ cells (Fig 3C). The expression correlation coefficient (r) of these splicing factors and all expressed genes between APLNR+ and PLB‐treated cells was 0.98 and 0.81, respectively (Fig EV4B and C). To determine the molecular mechanism underlying the impairment of EPC production, we identified differentially expressed splicing factors (FC > 1.5) by overlapping the highly expressed splicing factors in APLNR+ cells (DMSO‐treated EPCs vs. APLNR+ cells) and the highly expressed splicing factors in PLB‐treated cells (PLB‐ vs. DMSO‐treated EPCs; Fig 3D). This approach revealed 38 splicing factors. We used the protein–protein interaction network (STRING; Szklarczyk et al, 2019, https://string‐db.org) to analyze these factors (Fig EV4D) and discovered connecting nodes that included the constitutive components SNRPD1, SNRPE, and SF3A3 of the spliceosome and the splicing regulator SRSF2. Their dynamic expression pattern during hematopoietic differentiation, with or without PLB treatment, was further confirmed (Figs 3E and EV4E).

To ask whether dysregulation of splicing factors is deleterious to EPCs, we established hESC lines stably overexpressing the splicing factors SNRPD1, SNRPE, SF3A3, and SRSF2, using a DOX‐based inducible overexpression system with GFP as an indicator (Fig EV4F, G, and H). These cell lines, and the corresponding empty vector controls, were induced to undergo hematopoietic differentiation. At day 2.5, the cells were treated with 1 μg/ml DOX with or without 1.25 nM PLB until day 5 of differentiation (Fig 3F). At day 5, we FACS‐sorted GFP+ cells and confirmed the SRSF2 overexpression after DOX induction (Fig 3G). SRSF2 overexpression recapitulated the decrease in CD31+CD34+ EPC generation detected with PLB treatment (Fig 3H and I). However, the ectopic expression of other splicing components, such as SNPRD1, SNRPE, and SF3A3, had little impact on the generation of EPCs (Fig EV4G–J).

To further analyze the role of SRSF2 in CD31+CD34+ cell generation, we established DOX‐inducible SRSF2 knockdown stable hESC lines, using a strategy similar to that described for knockdown of SF3B1 (Fig EV3I). The reduced expression of SRSF2 was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig 3J). The cells were differentiated toward the hematopoietic lineage and DOX was added from day 2.5 to 5 to induce SRSF2 knockdown. At day 5 of differentiation, decreased SRSF2 expression enhanced CD31+CD34+ generation, in contrast to the impaired CD31+CD34+ generation with SRSF2 overexpression (Fig 3K and L). In summary, inhibition of the splicing factor switch contributes to impaired EPC formation.

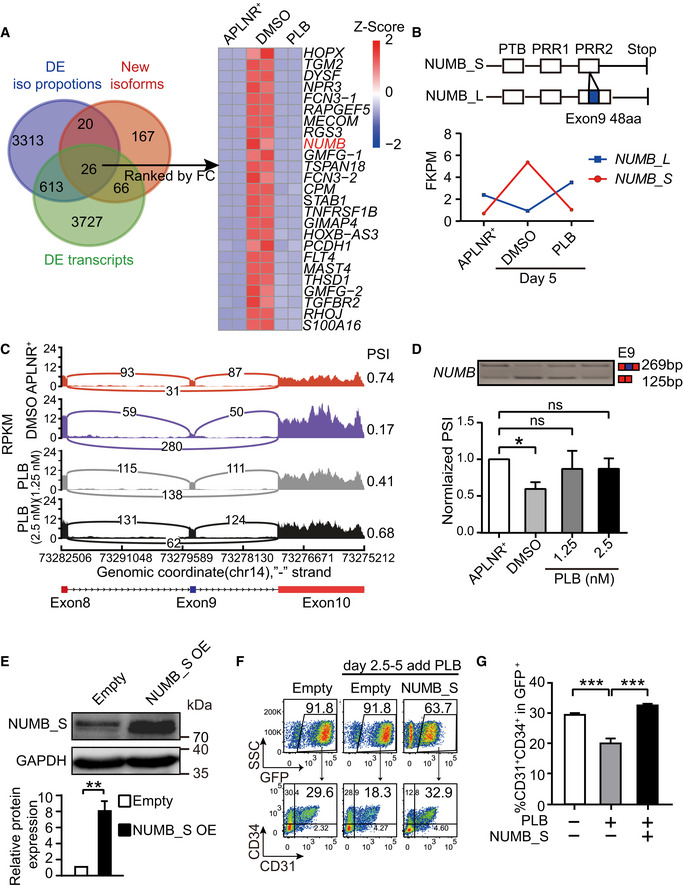

Dysregulation of alternative splicing of NUMB impairs EPC generation

To unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying EPC regulation by splicing, we analyzed genes with highly expressed isoforms (FPKM > 5) emerged during EPC generation (Fig 4A, pink circle). Additionally, genes exhibiting isoform proportion changes (delta iso > 0.15; blue circle; see Materials and Methods) or genes with differentially expressed isoforms (FC > 10 & FDR < 0.05; green circle) after PLB treatment (PLB vs DMSO) were filtered (Fig 4A). Their intersection revealed 26 candidate isoforms (from 24 genes) (Fig 4A), including NUMB, known for its roles in cell fate decisions (Yan, 2010). NUMB expression peaked in EPCs during hematopoietic development (Fig EV5A). NUMB exhibits multiple alternative splice variants that differ in the length of the phosphotyrosine‐binding (PTB) domain and proline‐rich region (PRR) domain (Verdi et al, 1999). The inclusion (long isoform) or exclusion (short isoform) of part of the PRR domain (a 48 amino acid‐encoded exon 9) generates two commonly studied isoforms (Yan, 2010). The dominantly expressed isoform in APLNR+ mesoderm cells contained exon 9 (the long isoform of NUMB, referred to as NUMB_L), whereas during EPC specification, a NUMB isoform lacking exon 9 emerged (the short isoform of NUMB, referred to as NUMB_S). The generation of NUMB_S was compromised by inhibiting splicing (Fig 4B). Sashimi plot and RT–PCR analysis revealed that PLB interfered with NUMB splicing to preferentially yield NUMB_L isoform (Fig 4C and D).

Figure 4. Linking alternative splicing of NUMB to EPC generation.

- The Venn diagram showing genes with significantly isoform changes. Pink circle represents genes with highly expressed isoform (FPKM > 5) that emerged during EPC generation. Blue circle represents genes exhibiting isoform proportion changes (delta iso > 0.15) after PLB treatment (PLB vs DMSO). Green circle represents genes with differentially expressed isoforms (FC > 10 and FDR < 0.05) after PLB treatment (PLB vs DMSO). The heatmap shows the expression of the overlapped genes ranked by FC when compared between DMSO vs PLB‐treated cells. The heatmap was scaled with Z‐Score using the log2(FPKM) expression of isoforms of indicated genes. n = 2 technical replicates

- The schematic representation (top) indicates the isoform structure of NUMB_L and NUMB_S. The bottom curve reflects the expression of NUMB isoforms in day 2‐APLNR+ cells, day 5‐DMSO‐treated, and day 5‐PLB (2.5 nM)‐treated cells.

- A Sashimi plot to visualize the mapping of RNA‐Seq reads at the exon 11‐13 loci of NUMB in day 2‐APLNR+ cells, day 5‐DMSO‐treated, and day 5‐PLB‐treated cells.

- The top panel is one representative RT–PCR electropherogram showing the inclusion/exclusion of NUMB exon 9 in day 2‐APLNR+, day 5‐DMSO‐treated, and day 5‐PLB‐treated cells. The expected isoforms are indicated on the right with exon 9 in blue and constant exons in red. At the bottom is a statistical bar graph of normalized PSI obtained from the RT–PCR electropherogram. P‐values were calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test.

- Western blotting showing NUMB_S overexpression in sorted GFP+ cells on day 5 during differentiation induced by DOX from day 2.5 to 5. GAPDH was used as the loading control. The bar graph presents the quantification of NUMB_S protein expression. The P‐value was determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test.

- The representative FACS plots show the frequency of CD31+CD34+ EPCs in the GFP+ population at day 5 with 1.25 nM PLB supplementation alone or in combination with NUMB_S ectopic expression from day 2.5.

- The bar graph denotes the percentage of CD31+CD34+ in GFP+ cells as described in (F). P‐values were determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test.

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD. ns represents no significant difference, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

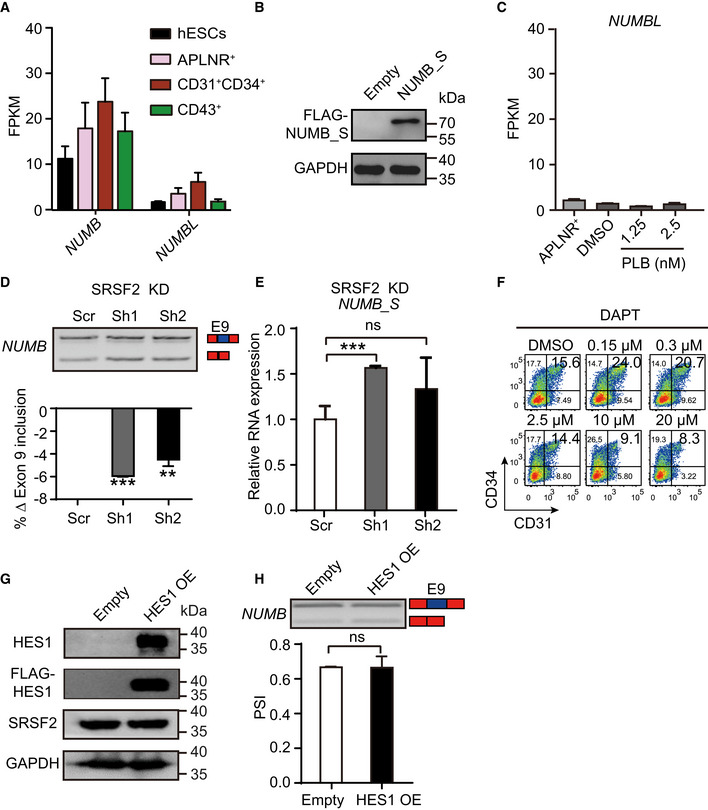

Figure EV5. NUMB Expression and its splicing regulation.

- Expression of NUMB and its family member NUMBLIKE (NUMBL) during human hematopoietic development by RNA‐Seq.

- Western blotting showing NUMB‐S overexpression upon DOX induction with anti‐FLAG antibody. The GAPDH gene was used as a loading control.

- Expression of NUMBL in day 2‐APLNR+ cells, day 5‐DMSO–treated, and day 5‐PLB‐treated cells.

- The upper panel is a representative RT–PCR electropherogram showing the inclusion or exclusion of NUMB exon 9 in SRSF2 depleted cells on day 5 of differentiation. The bar graph showing the changes of exon 9 inclusion obtained from the RT–PCR electropherogram.

- RT–qPCR measuring the expression of NUMB‐S in SRSF2 depleted cells on day 5 of differentiation.

- The representative FACS plots of CD31+CD34+ cells at day 5 of differentiation after treatment with DMSO and NOTCH inhibitor DAPT at various concentrations from day 2.5 to 5.

- Western blotting showing the expression of HES1 (detected by endogenous HES1 antibody as well as anti‐FLAG antibody) and SRSF2 in 293T cells. GADPH acts as a loading control.

- The splicing of NUMB exon 9 after HES1 overexpression. The top panel is a representative RT–PCR electropherogram showing the inclusion or exclusion of NUMB exon 9 without or with HES1 overexpression. The quantification is presented in the bottom bar graph.

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD. P‐values were determined by unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test in (D), (E), and (H). ns represents no significant difference. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To test whether the EPC‐specific isoform of NUMB_S regulates EPC generation, we established a NUMB_S stable overexpression cell line controlled by a DOX‐inducible system as described for SRSF2 (Fig EV4F). NUMB_S overexpression was confirmed by Western blotting with anti‐FLAG antibody (Fig EV5B). This NUMB_S stable cell line and a control cell line (empty vector) were induced to undergo hematopoietic differentiation, and the differentiated cells were treated with DOX (1 μg/ml) with or without PLB (1.25 nM) from day 2.5 to 5. At day 5 of differentiation, we FACS‐sorted GFP+ cells and confirmed the NUMB_S expression (Fig 4E). PLB‐induced defects in EPC generation were rescued by ectopic NUMB_S expression (Fig 4F and G). Thus, the alternative isoform of NUMB has an important role in EPC generation. Although NUMB and its homolog NUMBLIKE (NUMBL) share a similar expression pattern and execute redundant functions in multiple tissues, such as neuronal differentiation (Verdi et al, 1999) and erythroid development (Bresciani et al, 2010), NUMBL expression in hematopoietic differentiation was low and unaffected by PLB (Fig EV5A and C), indicating that NUMB and NUMBL are not likely to function redundantly during human hematopoietic differentiation.

SRSF2 regulates NUMB alternative splicing

We demonstrated that SRSF2 was downregulated during EPC generation (Fig 3D and E). Inhibition of splicing with decreased generation of EPCs (Fig 2D and G) and sustained high level of SRSF2 (Fig 3D and E). Ectopic expression of SRSF2 during EPCs generation recapitulated the reduced generation of EPCs obtained with PLB treatment (Fig 3H and I). NUMB_S overexpression rescued defective EPC induction resulting from splicing inhibition (Fig 4F and G). These results led us to test whether SRSF2 regulates NUMB splicing to control EPC generation.

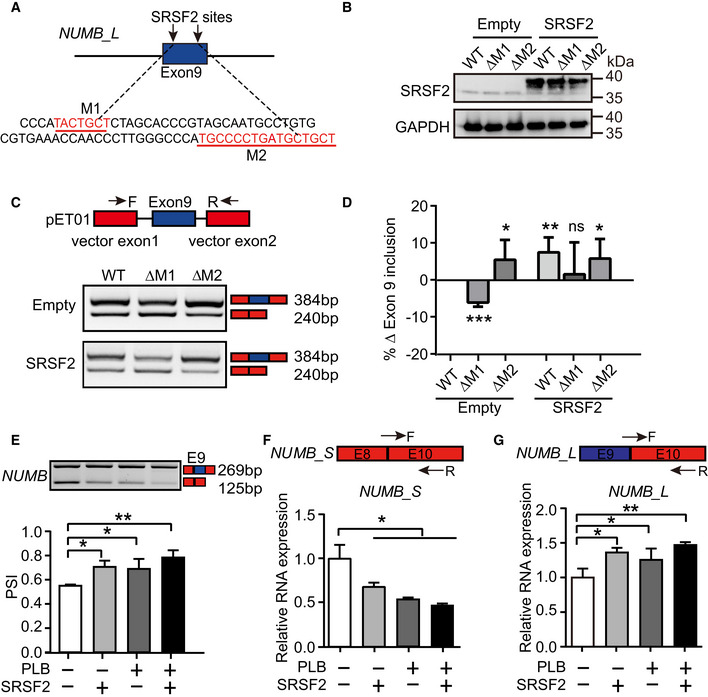

To determine whether SRSF2 regulates the alternative splicing of NUMB, we performed splicing motif prediction in NUMB exon 9 using RBPmap (Paz et al, 2014). Motif analysis revealed two putative SRSF2 binding motifs (M1 and M2) in exon 9 (labeled as red nucleotides; Fig 5A). To analyze whether SRSF2 regulates NUMB exon 9 splicing via these motifs, we performed a minigene splicing reporter assay (Rajendran et al, 2016). Three NUMB reporter plasmids (wild type (WT), M1 deletion (ΔM1), and M2 deletion (ΔM2)) were generated using sequences 540 nucleotides upstream and 507 nucleotides downstream of NUMB exon 9 and cloned into the reporter vector. Co‐transfection of SRSF2 overexpression plasmid with each NUMB reporter into 293T cells revealed that SRSF2 promoted the generation of NUMB_L isoform via M1 but not M2 (Fig 5B, C and D).

Figure 5. Splicing factor SRSF2 modulates NUMB exon 9 splicing.

-

AThe putative SRSF2 binding motifs on NUMB exon 9 (labeled as red), predicted by RBPmap. M1 refers to motif 1 and M2 refers to motif 2.

-

BWestern blotting showing the overexpression of SRSF2 in 293T cells, which was co‐transfected with NUMB reporters of WT, ΔM1, or ΔM2. ΔM1 or ΔM2 represents plasmid deleting corresponding binding site.

-

CA minigene splicing reporter assay showing SRSF2 promoted the generation of NUMB_L isoform via M1 but not M2. The upper panel indicating the pET01 vector that contains two constitutive NUMB exons. The representative RT–PCR electropherogram showing the expression of NUMB_L and NUMB_S isoforms in WT, ΔM1, or ΔM2 transfected 293T cells with or without SRSF2 overexpression, respectively.

-

DThe bar graph showing the normalized exon 9 inclusion from the RT–PCR electropherogram of (C) to the WT control cells. P‐values were determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test.

-

EOn day 5 of hematopoietic differentiation, the inclusion or exclusion of NUMB exon 9 were detected by RT–PCR with 1.25 nM PLB supplementation or SRSF2 exogenous expression alone or their combinational treatment from day 2.5. The bar graph showing the signaling intensity of each specific band from the RT–PCR electropherogram.

-

F, GThe top panel depicts the location of specific primers targeting NUMB_S and NUMB_L isoform. The bottom bar graph showing the expression of NUMB_S and NUMB_L in cells on day 5 of differentiation with 1.25 nM PLB supplementation or SRSF2 exogenous expression alone or their combinational treatment from day 2.5 with RT–qPCR.

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD. P‐values were calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test in (E), (F), and (G). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

During hematopoietic differentiation, the SRSF2 stably overexpressed cells and corresponding control (empty vector) cells were treated with DOX from day 2.5 to 5 with or without 1.25 nM PLB. On day 5, ectopic expression of SRSF2 or/and PLB administration promoted the inclusion of NUMB exon 9 (Fig 5E). PLB treatment or/and SRSF2 overexpression reduced the level of NUMB_S transcripts (Fig 5E and F) and induced a concomitant increase of NUMB_L transcripts in EPCs (Fig 5E and G). Upon decreased SRSF2 expression, we detected the decreased inclusion of NUMB exon 9 (Fig EV5D) and elevated NUMB_S expression (Fig EV5E). Thus, SRSF2 regulates NUMB exon 9 alternative splicing.

NUMB alternative splicing impacts NOTCH activity during EPC generation

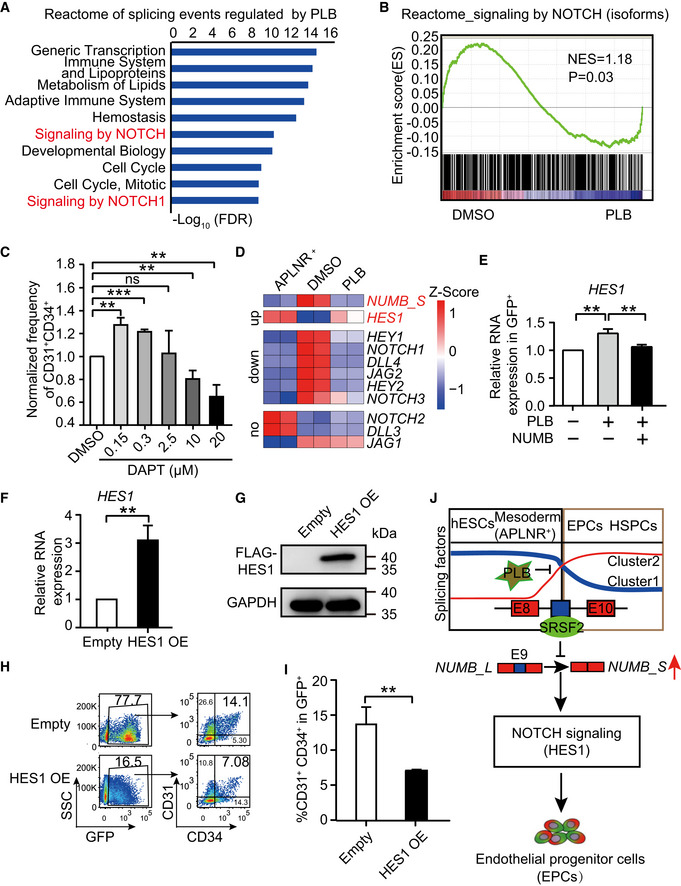

As NUMB is an endogenous NOTCH antagonist (Guo et al, 1996; Spana & Doe, 1996; McGill & McGlade, 2003), we investigated the relationship between NUMB AS and NOTCH signaling in EPC regulation. We conducted gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of genes containing the differential splicing events from the aforementioned RNA‐Seq data in PLB‐treated EPCs (Fig 3A). Among the top enriched GO terms, NOTCH signaling was strongly associated with differential splicing events (Fig 6A), consistent with gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; Fig 6B).

Figure 6. NUMB alternative splicing impacts NOTCH activity during EPC generation.

- The top 10 Reactome terms enriched from differential splicing events regulated by PLB. To define the differential splicing events, genes with FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage were selected. Among them, the differential splicing events were identified by the double cutoffs of delta PSI > 0.2 and FDR < 0.05.

- GSEA analysis of NOTCH signaling in isoform level between DMSO control and 2.5 nM of PLB‐treated cells.

- The bar graph representing the percentage of CD31+CD34+ cells at day 5 of differentiation after treatment with DMSO and various concentrations of DAPT starting from day 2.5.

- The heatmap plotting the expression of NUMB_S and the key components in NOTCH signaling in day 2‐APLNR+ cells, day 5‐DMSO–treated, and day 5‐PLB‐treated cells (2.5 nM), respectively. The NOTCH components were divided into groups of upregulated, downregulated, and unchanged by comparison between DMSO‐ and PLB‐treated cells. The heatmap was scaled with Z‐Score using the log2(FPKM) expression of indicated genes. n = 2 technical replicates

- RT–qPCR assay showing the expression of HES1 mRNA in the GFP+ cells on day 5 of differentiation with 1.25 nM PLB supplementation alone or in combination with NUMB_S ectopic expression from day 2.5.

- RT–qPCR analysis confirmed the overexpression of HES1 mRNA after DOX induction. The ACTB gene was used as a control. The data were normalized to the mRNA level in empty vector control cells.

- Western blotting showing the level of HES1 overexpression after DOX induction. The GAPDH gene was used as a loading control.

- The representative FACS plots indicating the generation of CD31+CD34+ EPCs on day 5 of differentiation with or without HES1 overexpression. DOX was treated from day 2.5 to 5 to induce HES1 overexpression.

- Statistical analysis of the percentage of CD31+CD34+ EPCs of (H).

- A hypothetical model. During hematopoietic differentiation from hESCs, a splicing factor switch occurs during the transition from mesoderm APLNR+ cells to EPCs. Concomitant with the switch of components in the splicing machinery, the splicing regulator SRSF2 is downregulated, leading to the enrichment of an EPC‐induced NUMB_S isoform. Alternative splicing of NUMB controls NOTCH activity, probably by suppressing HES1 expression and, ultimately, regulates EPC specification. The blue and red colors represent the two switching clusters within splicing factors during hematopoietic differentiation.

Data information: Results given are mean ± SD. P‐values were determined by an unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test in (C), (E), (F), and (I). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All experiments were conducted for at least 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To test whether NOTCH signaling controls EPC generation, we added DAPT, a commonly used γ‐secretase inhibitor that prevents NOTCH receptor activation, to the mesodermal cells at day 2.5 of differentiation. We found EPC generation was highly sensitive to DAPT treatment. The lower dose (0.15 and 0.3 μM) of inhibitor promoted EPC generation, while the higher dose repressed it, suggesting that the precise regulation of NOTCH signaling is required for EPC formation (Figs 6C and EV5F).

To identify the gene(s) in the NOTCH signaling pathway that may be linked to NUMB_S, we examined components of the NOTCH signaling pathway, including downstream transcription factors HES1, HEY1, and HEY2, NOTCH receptors NOTCH1‐4, NOTCH ligand DLL1‐2, and JAG1‐2. A number of these components were upregulated during EPC generation and downregulated after PLB treatment (Fig 6D). NUMB_S and the NOTCH transcription factor HES1 negatively correlated (Fig 6D and E). With the induction of the NUMB_S isoform during EPC generation, HES1 expression was reduced (Fig 6D). Treatment of cells with 1.25 nM PLB from day 2.5 to 5 during hematopoietic differentiation, NUMB_S was decreased due to aberrant splicing, while HES1 expression was elevated in CD31+CD34+ EPCs on day 5 of differentiation (Fig 6D and E). Moreover, the combined induction of NUMB_S and the inhibition of splicing with PLB restored HES1 expression to its normal level (Fig 6E). These results suggest that HES1 might function downstream of NUMB_S, directly or indirectly.

To test whether NUMB_S regulates NOTCH signaling by targeting HES1, we induced HES1 overexpression during hematopoietic differentiation from day 2.5 to 5 (Fig 6F and G). HES1 overexpression severely abolished EPC generation, thus phenocopying the results obtained with PLB treatment (Fig 6H and I). When HES1 was overexpressed in 293T cells, there was no apparent change of SRSF2 expression and NUMB splicing (Fig EV5G and H). Thus, the NUMB_S isoform controls NOTCH signaling and EPC differentiation.

Discussion

Using a hPSC‐based model to address the role of RNA processing in hematopoietic development, we discovered a splicing factor switch involved in the differentiation of mesoderm cells into EPCs (Fig 6J). Splicing inhibition perturbed this switch and decreased EPC generation. A mechanistically important consequence of aberrant splicing factor expression involved disrupted NUMB splicing. An EPC‐inducing NUMB isoform was significantly decreased, which resulted in downregulation of NOTCH activity and inhibited EPC specification (Fig 6J). Because the generation of EPC is an essential step from embryonic mesoderm to HSPCs during hematopoietic development, AS establishes the post‐transcriptional regulatory network as an important component of the hematopoietic differentiation program.

HSC transplantation is the only curative therapeutic strategy for various hematological malignancies. However, the broad application of HSC transplantation is limited due to the unavailability of matching HSCs. Although in vitro induction of HSCs from PSCs represents a promising approach for the generation of transplantable HSCs, hPSC‐derived HSCs exhibiting transplantable ability have been restricted to genetically modified HEPs (Sugimura et al, 2017). Thus, deciphering the molecular mechanisms that govern the generation and function of EPCs and HEPs remains a critical problem.

Our analysis of AS during hESC‐based hematopoietic differentiation uncovered a splicing factor switch occurring from the mesodermal APLNR+ cells to EPC generation. This switch was crucial for the establishment of the EPC‐specific transcriptome. Our analysis revealed the dynamic expression of spliceosome subcomplex components and provided evidence for the developmental stage‐specific expression of splicing factors. Thus, the splicing factor switch may generate new isoforms or alter the proportion of existing isoforms (e.g., NUMB_L and NUMB_S isoform) to facilitate lineage commitment. We propose that the stage‐specific splicing factor alteration may be common and functionally critical in diverse developmental processes. Not all developmental stages were equally sensitive to splicing inhibition. For example, splicing inhibition during ESC differentiation to mesoderm cells or EPC differentiation to HSPCs had only minor detrimental effects. EPC generation was uniquely susceptible to splicing inhibition due to the block of the splicing factor switch.

The adaptor protein NUMB is a key determinant of cell fate (Yan, 2010). NUMB modulates the primitive erythroid lineage development in both zebrafish (Bresciani et al, 2010) and mESC‐derived hematopoietic differentiation system (Cheng et al, 2008). However, how NUMB affects early hematopoietic development is not resolved. We demonstrated that NUMB regulates EPC generation by controlling NOTCH signaling in an isoform‐specific manner. In APLNR+ cells, NUMB is expressed predominantly as the exon‐9‐included NUMB_L isoform. During APLNR+ mesoderm differentiation into EPCs, NUMB_S is induced. Prior studies reported that NUMB_L is expressed in immature progenitor cells, whereas NUMB_S is expressed in more differentiated cells during neural or retinal development (Verdi et al, 1999; Dooley et al, 2003; Toriya et al, 2006; Bani‐Yaghoub et al, 2007; Rajendran et al, 2016). NUMB_L and NUMB_S isoforms have distinct roles in regulating cellular functions. Overexpression of NUMB_S in progenitor cells promotes proliferation, while ectopic expression of NUMB_L stimulates differentiation (Verdi et al, 1999; Dooley et al, 2003; Toriya et al, 2006; Bani‐Yaghoub et al, 2007; Rajendran et al, 2016). In our study, as overexpression of the NUMB_S isoform rescued EPC defects caused by PLB, the regulatory network governed by NUMB_S is important for EPC generation.

NUMB contains a highly conserved phosphotyrosine‐binding domain (PTB) in the N terminus and proline‐rich region domains (PRR) at the C terminus (Verdi et al, 1999). The C‐terminal PRR containing a putative Src homology 3’ binding site is involved in signal transduction (Gulino et al, 2010). Alternative exon 9 encodes a part of the PRR. The regulation of alternative exon 9 splicing has been reported by splicing factors and RNA binding proteins, e.g., SRSF1 and PTBP1 (Rajendran et al, 2016), SRSF3 (Ke et al, 2018), RBM10 (Bechara et al, 2013), RBM4 (Tarn et al, 2016), RBFOX2, and SRPK2 (Lu et al, 2015) in a variety of cells including 293T, breast cancer, lung cancer, neuronal, and hepatocellular carcinoma cells, respectively. During hESC hematopoietic differentiation, SRSF1 and SRSF3 shared a similar expression pattern as SRSF2, which was reduced from APLNR+ to CD31+CD34+ cells (Fig 1F). After PLB treatment, SRSF1 and SRSF3 sustained at high level (Fig 3D). Besides SRSF2, SRSF1, and SRSF3 might be important splicing regulators for NUMB during hematopoietic differentiation, which needs further investigations.

NOTCH signaling, especially NOTCH1, is essential for EHT (Zhang et al, 2015). NOTCH1 inactivation blocks EHT and abrogates HSC generation (Kumano et al, 2003). However, HSC maturation and development become NOTCH‐independent in the AGM (Souilhol et al, 2016). NOTCH signaling strength controls endothelial or hematopoietic lineage choice during hematopoietic development (Lee et al, 2013; Ayllon et al, 2015; Uenishi et al, 2018). NOTCH‐mediated arterialization of EPCs is essential for establishing the definitive hematopoietic program from hPSCs (Uenishi et al, 2018). Nevertheless, the contribution of NOTCH signaling to fate determination within mesoderm APLNR+ cells is still unclear. Analyses of hematopoiesis in early zebrafish embryos have shown that NOTCH signaling influences the development of endothelial and primitive erythroid cells from the lateral plate mesoderm cells (Lee et al, 2009; Chun et al, 2011). NOTCH signaling may increase primitive erythrocyte output at the expense of endothelial cells (Lee et al, 2009) and/or promote of endothelial precursor proliferation within the lateral plate mesoderm (Chun et al, 2011). We demonstrated that NOTCH activation is one of the key mechanisms governing EPC generation. The level of NOTCH activity is crucial for EPC generation, as attenuating its activity via inhibitor, or elevating its activity, through HES1 overexpression, impairs EPC generation from the lateral plate mesoderm progenitor cells. The fate determination of lateral mesoderm cells might therefore require the precise control of NOTCH signaling activity. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the control of NOTCH activity and EPC differentiation involves a balance of NUMB long and short isoforms.

Our global analysis of AS during hematopoiesis uncovered a new post‐transcriptional regulatory mechanism involving an SRSF2‐NUMB‐NOTCH axis that modulates EPC and HEP differentiation. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying EPC and HEP fate determination has potential to lead to the development of hPSC‐derived transplantable HSCs with utility in regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

hESCs monolayer hematopoietic differentiation system

The human ESC line (H1) was purchased from ATCC (#15570). Before inducing differentiation, hESCs colonies were pretreated with accutase (cat# A1110501, Invitrogen) to yield a single cell suspension. From this suspension, 3.5 × 104 cells were plated in each well of growth factors reduced (GFR) Matrigel‐coated 12‐well plates (cat# 354230, Corning) and cultured in mTESR1 media (cat# 85852, Stem cell) containing 10 μM of Y27632 (cat# 688000, Calbiochem) for 24 h. mTESR1 medium was then changed to mTESR1 medium without select factors (cat# 05892, Stem cell) with a supplement of 50 ng/ml of Activin A (cat# 120‐14‐1000, Peprotech) and 40 ng/ml of BMP4 (cat# 120‐05ET‐1000, Peprotech) and kept for two days to induce the APLNR+ lateral plate mesoderm. Next, 50 ng/ml of bFGF (cat# 100‐18B‐100, Peprotech) and 40 ng/ml of VEGF (cat# 100‐20‐100, Peprotech) were added to the mTESR1 medium without select factors from day 3 to 8 to induce CD31+CD34+ EPCs on day 5 and CD43+ HSPCs on day 8.

Fluorescence‐activated cell sorting assay

The cells were dissected into single cells, washed, and resuspended in ice‐cold phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) with 2% FBS (Cat# 10270, Gibco). For each assay, 1 × 105 cells were suspended in 100 μl of PBS with 2% FBS and stained with 0.2 μg of conjugated antibody at 4°C for 30 min in the dark (Liu et al, 2018b). The primary antibodies used for flow cytometry were as follows: PE cyanine 7 Mouse IgG1 (cat# 25‐4714‐42, eBioscience), APC Mouse IgG3 (cat#1C007A, R&D), PE IgG1 (cat# 555719, BD Bioscience), CD31 (cat# 555446, BD Biosciences), CD34 (cat# 555824, BD Biosciences), h‐APJ (cat# FAB856A, R&D), CD73 (cat# 561258, BD Biosciences), and CD43 (cat# 560978, eBioscience). Cells were then washed once and resuspended in 300 μl of pre‐chilled PBS containing 2% FBS. Before subjected to flow‐cytometric analysis, the cells were incubated with DAPI for 5 min and analyzed on a FACS CANTO II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed with FlowJo version 10.

Cell cycle and apoptosis assay

For cell cycle analysis, cells were dissected into single cells by accutase and washed once with PBS. Next, they were labeled with an APC‐conjugated CD31 antibody at 4ºC for 20 min in the dark. After washing, the cells were suspended in 500 μl of PBS to which was added 5 ml of cold ethanol (−20ºC) with repeated pipetting and incubated at 4ºC overnight. The next day, the cells were washed with 2 ml of cold PBS supplemented with 1% BSA (Cat# A1595, Sigma) twice and incubated with 200 μl of staining buffer containing 20 μl of PI solution (0.5 mg/ml), 20 μl of RNase A (10 mg/ml), 160 μl PBS supplemented with 1% BSA, and 0.1% Triton X‐100 at 37ºC in the dark for 45 min.

For apoptotic analysis, 1 × 105 single cells were incubated with 1 μl of Annexin V in 100 μl of binding buffer for 10–15 min at room temperature. Then, 10 μl of 7‐AAD was added to each tube and kept for 5 min. The CANTO II flow cytometer was used to test the samples and data analysis was performed by FlowJo (version 10).

Endothelial cell culture and LDL uptake assay

During hematopoietic differentiation, cells were treated with DMSO or 1.25 nM PLB from day 2.5. At day 5, FACS‐purified CD31+ cells were plated on a collagen‐coated‐6‐well plate (1 × 105 cells per well) in EBM‐2 (cat# CC‐3156, Lonza) media supplemented with 15% KnockOut Serum Replacement (cat# 10828028, Thermo Fisher), 5 ng/ml of EGF, 5 ng/ml of FGF‐2, 10 ng/ml of IGF‐1, 10 ng/ml of VEGF, 1 μg/ml of hydrocortisone (cat# H0888, Sigma), 1 IU/ml of heparin (cat# H3149‐500KU‐9, Sigma), and 20 μg/ml of L‐ascorbic acid (cat# A8960‐5G, Sigma). After cultured for additional 5 days, cells were dissected into single cells for the acetylated low‐density lipoprotein (AcLDL, cat# L23380, Invitrogen) uptake assay. Cells were incubated with 10 ng/ml of Alexa 488‐conjugated AcLDL (cat# 1848459, Invitrogen) for an additional 12 h and then fixed for immunofluorescence with anti‐CD144 antibody (cat# 561567, BD Biosciences). The LDL fluorescence intensity was measured with Volocity 3D image analysis software.

Real‐time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol™ (cat# 15596018, Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using TransScript II One‐Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (cat#N10613, TransGen Biotech) to with 500 ng of total RNA. RT–qPCR was performed using the SYBR green master mix kit (cat# A25742, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the assay was conducted with the QuantStudio®5 Real‐Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The primers used are listed in Table EV1.

Establishing inducible overexpression stable hESC lines

SRSF2, SF3A3, SNRPD1, SNRPE, NUMB‐S, and HES1 cDNAs were amplified from H1 cDNA or purchased from company (BGI, China). They were cloned into the tet‐on inducible piggybac transposon expression vector (Yusa et al, 2011), co‐expressing the GFP (P2A GFP) and possessing puromycin resistance. The plasmids were co‐transfected with transposase to H1 with the Lipofectamine Stem reagent (cat# L3000015, Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty‐four hours after transfection, 1 μg/ml puromycin was added to the culture media for selection for approximately 10 days until nearly no dead cells observed. The cells were induced by 1 μg/ml DOX for 2.5 days to assess GFP expression. The GFP+ cells reaching ~ 90% were referred as stable cell lines, and the expression of target genes was measured by Western blotting. The primers used are listed in Table EV1.

Establishing inducible knockdown stable hESC lines

The SF3B1 and SRSF2 shRNAs and a scrambled shRNA (Scr) were cloned into a DOX‐inducible lentiviral pLKO‐Tet‐On vector (Wiederschain et al, 2009) with puromycin resistance and packaged in 293T cells. H1 cells, which were pre‐seeded as single cells onto Matrigel‐coated plates at the density of 1 × 105 cells/ml for 24 h, were infected by the lentiviral particles with 8 μg/ml polybrene. The infected cells were selected with 0.3 μg/ml puromycin for 21 consecutive days until nearly no dead cells observed. Then, the cells were induced by 1 μg/ml DOX for 2.5 days to examine the target gene expression by Western blotting. The primers used are listed in Table EV1.

Western blotting

Each group of 1 × 105 cells was lysed with 100 μl NP40 buffer containing protease inhibitor and 1 mM of DTT (cat# 18064‐071, Invitrogen). Fifteen to thirty microliters of protein solution were resolved by SDS–PAGE (cat# CW0027, CWBIO), transferred to nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes, and probed with primary antibodies. The primary antibodies used for Western blotting were as follows: anti‐SRSF2 (cat# PA5‐62086, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti‐HES1 (cat# ab71559, Abcam), anti‐NUMB (cat# A9352, ABclonal), anti‐SF3B1 (27684‐1‐AP, ProteinTech), anti‐GAPDH (cat# AP0063, Bioworld), and anti‐FLAG (cat# F1804, Sigma). HRP‐conjugated anti‐rabbit (cat# NA934V, GE) and anti‐mouse (cat# NA931V, GE) secondary antibodies were used and membranes were incubated with the Western ECL Substrate (cat# WBKLS0500, Millipore). Signals were detected using a ChemiDoc Imaging system (Bio‐Rad).

Minigene reporter assay

We constructed a truncated NUMB reporter, encompassing a genomic fragment from 540 nucleotides upstream to 507 nucleotides downstream of NUMB exon 9. This reporter plasmid was then cloned into an ExonTrap pET01 vector (a generous gift from Dr. Jingyi Hui, Chinese Academy of Sciences) which contains two constitutive exons, as reported previously (Rajendran et al, 2016). Meanwhile, we also constructed two mutant NUMB reporters by deleting each putative binding site, respectively. 293T cells were seeded in a 12‐well plate with 3 × 105 cells/well for 24 h before transfection. Then, pET01 reporter, harboring plasmid of wild‐type NUMB exon 9 (WT) or mutants, were co‐transfected with or without SRSF2 overexpression vector into the pre‐seeded 293T cells. After 12–16 h of transfection, the cells were treated with 1 μg/ml DOX to induce SRSF2 expression. The cells were harvested for RNA extraction after 36 h of DOX induction. Upon reverse transcription, the cDNA was amplified by PCR with specific primer loading in pET01 reporter vector, followed by electrophoresis. Finally, the intensity of the band from each lane was quantified with ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, cat# BL539A, Biosharp) at room temperature for 20 min. After washing with PBS, they were permeabilized by 0.2% PBT (Triton X‐100 + PBS) for 15 min. Then, the cells were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h before incubation with primary antibodies in a ratio of 1:200 at 4ºC overnight. The next day, after incubation with secondary antibodies followed by incubation with DAPI (cat# D9542, Sigma), the cells were ready for detection under a microscope.

RNA‐Seq

Total RNAs were extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Cat# 15596026). Library construction and data processing were performed by BGI (Beijing, China). The RNA integrity was measured by Agilent 2100 and rRNAs were removed with Epicenter Ribo‐ZeroTM Kit (Epicenter). The remaining RNAs were fragmented (250–300 bp) and reverse transcribed using random hexamers. Followed by purification, terminal repair, polyadenylation, adapter ligation, size selection, and degradation of second‐strand U‐contained cDNA, the strand‐specific cDNA library was generated. The cDNA was sequenced with an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform and 101 bp paired‐end reads were generated.

Quantification of gene and isoform expression

The human reference genome (version: GRCh38/hg38) and gene model (GTF file, GENCODE version 27) were obtained from https://www.gencodegenes.org/. Reads were aligned to the genome using STAR (version 2.5.3) with default settings. The resulting BAM file containing aligned reads were then taken as input for Cufflinks (version 2.2.1) to quantify gene and isoform expression with default settings. The expression level was measured by fragment per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM). We selected genes with FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage for all RNA‐Seq analysis.

Alternative splicing analysis

Percent spliced‐in (PSI) was used to quantify alternative splicing events. MISO (version 0.5.4) was used with default settings to calculate PSI of splicing events for each sample. The genes with FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage were filtered for further analysis. Among them, splicing events with PSI between 0.05 and 0.95 were used for differential splicing events analysis by rMATS (version 4.0.2) with default settings. The significantly differential splicing events were identified with delta PSI > 0.2 and FDR < 0.05.

Isoform proportion, which is calculated as the expression of an individual isoform to the sum of all isoforms belonging to the same gene, is a metric to quantify the activity of splicing at the isoform level (Monlong et al, 2014). To investigate isoform proportion between two consecutive stages, genes with FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage were selected. For these genes, isoforms with FPKM > 0.2 were retained for further analysis. Delta isoform proportion > 0.15 was considered significantly differential.

DESeq2 (version 1.20.0; Love et al, 2014) with default settings was used to identify differentially expressed genes and isoforms between two consecutive differentiation stages. The genes with FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage were considered and the raw count data was used as input.

Gene set associated with splicing

Splicing factors were collected from splicing‐related GO terms from Reactome and PathCards database. Among them, there were 235 splicing factors expressed with FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage, which were used for the splicing factor expression analysis. The components in major and minor spliceosome were similarly collected in Reactome and PathCards database. The expression of splicing factors, components in major spliceosome, and components in minor spliceosome during hematopoietic differentiation are listed in the Dataset EV1.

Cluster analysis

Heatmaps were generated using the R package Pheatmap (version 3.5.0). In hierarchical clustering, Euclidean distance was used to calculate the distance between genes, and complete linkage was used as the agglomeration method.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was conducted by the GSEA software (version 3.0) from the Broad Institute (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). To generate the input isoform expression matrix, isoforms (FPKM > 0.2) from genes with FPKM > 1 in at least one differentiation stage were selected. The numbers of permutations were set to 1000. All P‐values were corrected for multiple testing and the threshold for significant enrichment is set to FDR < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as mean ± SD except where indicated otherwise. For multiple comparisons, we performed one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test or Tukey’s test to determine statistical significance, as indicated in figure legends. For analysis shown in the boxplot graph, we performed two‐tailed Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. For others, we performed two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. For Bioinformatics analysis with multiple testing, the threshold for significant enrichment is set to FDR < 0.05.

Author contributions

YL, DW, HW, and XH performed all the experiments with help from YW, BRW, CX, JG, JL, JT, MW, PS, SR, FM. YL performed bioinformatics analysis with help from H‐DL. All authors were involved in the interpretation of data. LS and JZ conceived and supervised the project and wrote the manuscript with the help from EHB, YL, DW, and HW.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Dataset EV1

Source Data for Expanded View and Appendix

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Source Data for Figure 6

Acknowledgements

We thank all members in Dr. Shi’s and Dr. Zhou’s labs for their insightful discussions during the course of this work. This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China Stem Cell and Translational Research (grant number 2016YFA0102300, 2017YFA0103100 and 2017YFA0103102); CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (grant number 2016‐I2M‐1‐018, 2016‐I2M‐3‐002 and 2017‐12M‐1‐015); Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (grant number 81870089, 81530008, 31671541, 81700105, and 81890990).

EMBO Reports (2021) 22: e50535.

Contributor Information

Jiaxi Zhou, Email: zhoujx@ihcams.ac.cn.

Lihong Shi, Email: shilihongxys@ihcams.ac.cn.

Data availability

RNA‐Seq data are deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession GSE134907 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE134907) and GSE146147 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE146147).

References

- Ayllon V, Bueno C, Ramos‐Mejia V, Navarro‐Montero O, Prieto C, Real PJ, Romero T, Garcia‐Leon MJ, Toribio ML, Bigas A et al (2015) The Notch ligand DLL4 specifically marks human hematoendothelial progenitors and regulates their hematopoietic fate. Leukemia 29: 1741–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bani‐Yaghoub M, Kubu CJ, Cowling R, Rochira J, Nikopoulos GN, Bellum S, Verdi JM (2007) A switch in numb isoforms is a critical step in cortical development. Dev Dyn 236: 696–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baralle FE, Giudice J (2017) Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18: 437–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa‐Morais NL, Irimia M, Pan Q, Xiong HY, Gueroussov S, Lee LJ, Slobodeniuc V, Kutter C, Watt S, Colak R et al (2012) The evolutionary landscape of alternative splicing in vertebrate species. Science 338: 1587–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara EG, Sebestyén E, Bernardis I, Eyras E, Valcárcel J (2013) RBM5, 6, and 10 differentially regulate NUMB alternative splicing to control cancer cell proliferation. Mol Cell 52: 720–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bholowalia P, Kumar A (2014) EBK‐means: a clustering technique based on elbow method and K‐means in WSN. Int J Comput Applications 105: 17–24 [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani E, Confalonieri S, Cermenati S, Cimbro S, Foglia E, Beltrame M, Di Fiore PP, Cotelli F (2010) Zebrafish numb and numblike are involved in primitive erythrocyte differentiation. PLoS One 5: e14296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesana M, Guo MH, Cacchiarelli D, Wahlster L, Barragan J, Doulatov S, Vo LT, Salvatori B, Trapnell C, Clement K et al (2018) A CLK3‐HMGA2 alternative splicing axis impacts human hematopoietic stem cell molecular identity throughout development. Cell Stem Cell 22: 575–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challen GA, Goodell MA (2010) Runx1 isoforms show differential expression patterns during hematopoietic development but have similar functional effects in adult hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol 38: 403–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Kostadima M, Martens JHA, Canu G, Garcia SP, Turro E, Downes K, Macaulay IC, Bielczyk‐Maczynska E, Coe S et al (2014) Transcriptional diversity during lineage commitment of human blood progenitors. Science 345: 1251033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, Zeigler BM, Dzierzak E, Speck NA (2009) Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature 457: 887–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Huber TL, Chen VC, Gadue P, Keller GM (2008) Numb mediates the interaction between Wnt and Notch to modulate primitive erythropoietic specification from the hemangioblast. Development 135: 3447–3458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K‐D, Vodyanik MA, Togarrati PP, Suknuntha K, Kumar A, Samarjeet F, Probasco MD, Tian S, Stewart R, Thomson JA et al (2012) Identification of the hemogenic endothelial progenitor and its direct precursor in human pluripotent stem cell differentiation cultures. Cell Rep 2: 553–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun CZ, Remadevi I, Schupp MO, Samant GV, Pramanik K, Wilkinson GA, Ramchandran R (2011) Fli+ etsrp+ hemato‐vascular progenitor cells proliferate at the lateral plate mesoderm during vasculogenesis in zebrafish. PLoS One 6: e14732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilova N, Kumagai A, Lin J (2010) p53 upregulation is a frequent response to deficiency of cell‐essential genes. PLoS One 5: e15938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Garza A, Cameron RC, Nik S, Payne SG, Bowman TV (2016) Spliceosomal component Sf3b1 is essential for hematopoietic differentiation in zebrafish. Exp Hematol 44: 826–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pater E, Kaimakis P, Vink CS, Yokomizo T, Yamada‐Inagawa T, van der Linden R, Kartalaei PS, Camper SA, Speck N, Dzierzak E (2013) Gata2 is required for HSC generation and survival. J Exp Med 210: 2843–2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditadi A, Sturgeon CM, Tober J, Awong G, Kennedy M, Yzaguirre AD, Azzola L, Ng ES, Stanley EG, French DL et al (2015) Human definitive haemogenic endothelium and arterial vascular endothelium represent distinct lineages. Nat Cell Biol 17: 580–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]