Key Points

Question

Is there an association between dietary niacin intake and the risk of new-onset hypertension?

Findings

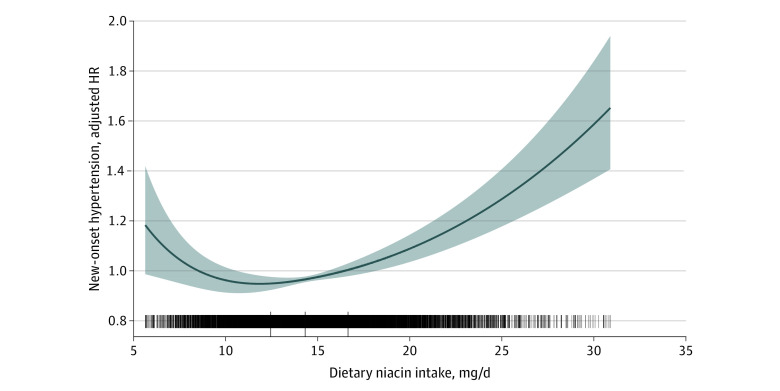

In this nationwide cohort study, a J-shaped association was found between dietary niacin intake and new-onset hypertension in Chinese adults, with an inflection point at about 15.6 mg/d and minimal risk between 14.3 and 16.7 mg/d of dietary niacin intake.

Meaning

The results of this study provide evidence that maintaining optimal dietary niacin intake levels may support the primary prevention of hypertension.

This cohort study of a large nationwide database of Chinese adults assesses the association between dietary niacin intake and the risk of new-onset hypertension.

Abstract

Importance

The relationship of dietary niacin intake with the risk of hypertension remains unknown.

Objective

To determine the prospective association between dietary niacin intake and new-onset hypertension, and examine factors that may modify the association among Chinese adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nationwide cohort study of 12 243 Chinese adults used dietary intake data from 7 rounds of the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Dietary intake was measured by 3 consecutive 24-hour dietary recalls from participants in combination with a weighing inventory taken over the same 3 days at the household level. Statistical analysis was conducted from May 2020 to August 2020.

Exposures

Dietary intake.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The study outcome was new-onset hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure 140 mm Hg or greater and/or diastolic blood pressure 90 mm Hg or greater, diagnosis by physician, or current antihypertensive treatment during the follow-up.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the study population was 41.2 (14.2) years, and 5728 (46.8%) of participants were men. The mean (SD) dietary niacin intake level was 14.8 (4.1) mg/d. A total of 4306 participants developed new-onset hypertension during a median (interquartile range) follow-up duration of 6.1 (3.6-11.3) years. When dietary niacin was assessed in quartiles, the lowest risk of new-onset hypertension was found in participants in quartile 3 (14.3 to <16.7 mg/d; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) compared with those in quartile 1 (<12.4 mg/d). Consistently in the threshold analysis, for every 1 mg/d increase in dietary niacin, there was a 2% decrease in new-onset hypertension (adjusted HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00) in those with dietary niacin intake less than 15.6 mg/d, and a 3% increase in new-onset hypertension (adjusted HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.04) in participants with dietary niacin 15.6 mg/d or greater. Based on these results, there was a J-shaped association between dietary niacin intake and new-onset hypertension in the general population of Chinese adults, with an inflection point at 15.6 mg/d and a minimal risk at 14.3 to 16.7 mg/d (quartile 3) of dietary niacin intake.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this study provide some evidence for maintaining the optimal dietary niacin intake levels for the primary prevention of hypertension.

Introduction

Hypertension is a leading cause of noncommunicable diseases, mortality, and disability worldwide.1,2,3 Approximately one-third of the adult population, or more than 300 million people, had hypertension in China between 2014 and 2015.4,5 Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify high-risk individuals and develop effective primary prevention strategies to reverse the rapidly rising trend of hypertension.

Niacin, also known as nicotinic acid or vitamin B3, is a vitamin precursor of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and is therefore essential for energy metabolism and redox reactions.6 Studies have shown that niacin supplementation may regulate abnormal lipid metabolism, improve endothelial function, and have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.7 Nevertheless, excessive niacin is also engaged in numerous pathologies, including insulin resistance and elevated homocysteine (HCY) levels.8,9 Several randomized clinical trials have assessed the effect of niacin supplementation on blood pressure (BP), but the results were inconsistent.10,11,12,13,14,15 Of note, these trials mainly examined the effects of relatively high niacin supplementation in high-risk populations rather than the effects of dietary niacin derived from foods in general populations. The dietary sources of niacin mainly include cereals and cereal products, meat and meat products, and vegetables.16 However, to date, research on the association between dietary niacin intake and hypertension is limited, and the prospective association between dietary niacin intake and incident hypertension risk remains unknown in the general population.

To address these knowledge gaps, our present study aimed to investigate the prospective association between dietary niacin intake and the risk of new-onset hypertension and to examine factors that may modify the association in the general population using data from the nationwide China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS).

Methods

Study Design and Population

Details on the study design and major results of the CHNS have been described previously.17,18,19 In brief, the CHNS is an ongoing multipurpose longitudinal open cohort study established in 1989, with follow up scheduled for every 2 to 4 years. A multistage, random cluster approach was used to sample the study population from 9 provinces (Heilongjiang [enrolled in 1997], Liaoning, Shandong, Henan, Jiangsu, Hubei, Hunan, Guizhou, and Guangxi) and 3 of China’s largest autonomous cities (Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing [all enrolled in 2011]). The CHNS rounds were conducted in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011, and 2015. By 2011, the CHNS included 12 provinces and autonomous cities and 288 communities; the provinces included in the CHNS constituted 47% of China’s population.20

We conducted a prospective cohort study based on 7 rounds of the CHNS data from 1997 to 2015. We first excluded participants who were pregnant, younger than 18 years, or with missing BP data. Among the remaining participants, those who were surveyed in at least 2 study rounds (15 774 participants; 61 612 person-waves) were included, and the first survey round was considered as baseline. The included population did not differ in most of the baseline characteristics from those not included (14 888 person-waves) (eFigure 1, eTable 1 in the Supplement). Of the 15 774 participants, we further excluded participants with hypertension (defined as having systolic blood pressure [SBP] ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure [DBP] ≥90 mm Hg, previous diagnosis by physician, or currently receiving antihypertensive treatment) at the time of the first survey. Furthermore, participants with missing dietary niacin data or with extreme dietary energy data (for men, >8000 or <800 kcal/d; women, >6000 or <600 kcal/d) were also excluded. Overall, a total of 12 243 participants were enrolled in the final analysis (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

The institutional review boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety, and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention approved the study. Each CHNS participant provided their written informed consent. The data, as well as study materials that support the findings of this study, are available at the CHNS website.21 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Dietary Nutrient Intakes

Both individual and household-level dietary data in the CHNS were collected by trained nutritionists through face-to-face interviews in each survey round. Individual diet was repeatedly assessed by 3 consecutive 24-hour dietary recalls at the individual level in combination with a weighing inventory over the same 3 days at the household level.22 The 3 consecutive days were randomly allocated from Monday to Sunday and are almost equally balanced across the 7 days of the week for each sampling unit. Nutrient intakes were calculated using the China food composition tables. Specifically, our analysis did not include the dietary data from the 1989, 1991, or 1993 waves because the food codes in those data sets did not match the food codes in the composition tables (the matching codes were not publicly released). The accuracy of 24-hour dietary recall designed to assess energy and nutrient intake has been validated.22 In the analyses, 3-day average intakes of dietary macronutrients and micronutrients in each round were calculated.

In this study, we evaluated the energy-adjusted nutrient intake for dietary niacin using residual method.23 Cumulative intake values of each nutrient were calculated for each participant using all results up to the last visit prior to the date of new-onset hypertension (or all results for participants without new-onset hypertension) to represent long-term dietary intake and minimize within-person variation.

Blood Pressure Measurements

Seated blood pressure measurements were obtained by trained research staff after the patients had rested for 5 minutes using a mercury manometer, following the standard method and with appropriately sized cuffs at each follow-up survey. Triplicate measurements on the same arm were taken in a quiet and bright room. The mean SBP and DBP of the 3 independent measures were used in analysis.

Assessment of Covariates

Information on age, sex, urban or rural residence, region, education level (eg, illiteracy, primary school, middle school, and ≥high school), occupation (eg, farmer, worker, unemployed, and others), and smoking and drinking status were obtained from the questionnaires at each follow-up survey. Smoking was defined by whether participants had ever smoked cigarettes (including hand-rolled or device-rolled), and drinking was defined by whether participants had ever drunk beer or any other alcoholic beverage. Height, weight, and waist and hip circumference were measured following a standard procedure with calibrated equipment. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

The questionnaire on physician-diagnosed hypertension and antihypertensive treatment included the following questions: “(1) Has a doctor ever told you that you suffer from high blood pressure? If yes, (2) for how many years have you had it? and (3) are you currently taking anti-hypertension drugs?” In China, the clinical diagnosis and treatment of hypertension were mainly according to the Chinese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension (1999, 2005, 2010, and 2018 versions). In all versions, hypertension was defined as a clinical SBP of 140 mm Hg or greater and/or DBP 90 mm Hg or greater without the use of antihypertensive medications. Overall, all the physicians used the same criteria for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of hypertension during the follow-up period.

Study Outcome

The study outcome was new-onset hypertension, defined as mean SBP≥140 mm Hg and/or mean DBP≥90 mm Hg, diagnosis by physician, or current antihypertensive treatment during the follow-up. When a participant was first identified with new-onset hypertension in a follow-up survey, the middle date between this and the nearest survey before was used to calculate the follow-up time. For those free of hypertension in all follow-up surveys, the last survey date was used to calculate the follow-up time.

Statistical Analysis

We assumed that the annual incident hypertension rate of Chinese adults with low dietary niacin was about 6% (with a type I error rate of .05), and so an enrollment of approximately 3000 participants in each group stratified by dietary niacin intake (eg, low, medium, high) would be necessary to provide more than 80% power to observe hazard ratios (HRs) of 1.2 or more for the comparison between low and high vs medium dietary niacin group during a follow-up period of about 6 years. Thus, a sample size of about 10 000 would be required.

Statistical analysis was conducted from May 25, 2020, to August 6, 2020. The population characteristics are presented as mean (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables by quartiles of dietary niacin. The differences in population characteristics were compared using ANOVA tests or χ2 tests.

The association of dietary niacin intake with new-onset hypertension were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models before and after adjustments for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, SBP, DBP, region, education, and occupation, as well as energy intake and sodium to potassium (Na/K) intake ratio. Threshold analysis in the association of dietary niacin intake with the study outcome was conducted with a 2-piecewise Cox regression model using a smoothing function. The threshold level (ie, inflection point) was determined using a likelihood-ratio test and bootstrap resampling methods.

Furthermore, possible modifications of the association between dietary niacin and new-onset hypertension were evaluated for the following variables: age (<40 [median] vs ≥40 years), sex, BMI (<25 vs ≥25), waist to hip ratio (<0.85 [median] vs ≥0.85), smoking status, drinking status, SBP (<120 vs ≥120 mm Hg), sodium to potassium intake ratio (<2.8 [median] vs ≥2.8), potassium (<1.4 [tertile 1] vs ≥1.4 g/d), sodium (<3.7 [tertile 1] vs ≥3.7 g/d), fat (<70.9 [median] vs ≥70.9 g/d), protein (<65.4 [median] vs ≥65.4 g/d), carbohydrate (<305.9 [median] vs ≥305.9 g/d), energy (<2162.0 [median] vs ≥2162.0 Kcal/d), fruit intake (0 vs >0 g/d) and vegetable intake (<356.4 [median] vs ≥356.4 g/d), residence (urban vs rural), and education level (≤primary school vs ≥middle school). Heterogeneity across subgroups was assessed by Cox proportional hazards models, and interactions between subgroups and dietary niacin intake were examined by likelihood ratio testing.

A 2-tailed P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant in all analyses. R software, version 3.6.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing) was used for all data analyses.

Results

Study Participants and Baseline Characteristics

Our study included 12 243 participants with complete dietary niacin intake measurements from the CHNS (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The mean (SD) age of the study population was 41.2 (14.2) years, and 5728 (46.8%) of the participants were men. The mean (SD) and median (interquartile range [IQR]) of dietary niacin intake were 14.8 (4.1) and 14.3 (12.4-16.7) mg/d (to convert niacin to μmol/d, multiply by 8.123), respectively. Baseline characteristics of study participants are presented by quartiles of dietary niacin in Table 1. Participants with higher dietary niacin intake had lower BMI, SBP, and DBP; lower percentages of residence in east and central regions; higher percentages of urban residence, higher education levels, and higher intake of fat, protein, potassium, and fruit and vegetables; lower intake of energy, carbohydrates, and sodium; and a lower sodium to potassium intake ratio. They were also younger and more likely to be men, smokers, and drinkers and less likely to be farmers (Table 1).

Table 1. Population Characteristics by Quartiles of Dietary Niacin Intake.

| Variable | Participants, No. (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (<12.4 mg/d) (n = 3061) | Q2 (12.4 to <14.3 mg/d) (n = 3060) | Q3 (14.3 to <16.7 mg/d) (n = 3061) | Q4 (≥16.7 mg/d) (n = 3061) | ||

| Men | 1340 (43.8) | 1317 (43.0) | 1399 (45.7) | 1672 (54.6) | <.001 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 41.5 (14.6) | 42.0 (14.3) | 40.7 (14.0) | 40.5 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | |||||

| Systolic | 114.5 (11.3) | 113.8 (11.5) | 113.1 (11.5) | 114.2 (11.4) | <.001 |

| Diastolic | 74.3 (7.9) | 74.3 (7.9) | 73.6 (7.8) | 74.4 (7.8) | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22.7 (3.1) | 22.2 (3.0) | 22.2 (3.0) | 22.5 (3.1) | <.001 |

| Waist to hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Smoking status | 882 (28.9) | 853 (28.1) | 920 (30.2) | 1053 (34.5) | <.001 |

| Drinking status | 972 (32.1) | 931 (30.9) | 1019 (33.7) | 1242 (40.9) | <.001 |

| Urban residence | 926 (30.3) | 940 (30.7) | 1170 (38.2) | 1379 (45.1) | <.001 |

| Region | |||||

| East and central | 2187 (71.4) | 1505 (49.2) | 1398 (45.7) | 1421 (46.4) | <.001 |

| Northeast and north | 525 (17.2) | 779 (25.5) | 614 (20.1) | 571 (18.7) | |

| Southwest and south | 349 (11.4) | 776 (25.4) | 1049 (34.3) | 1069 (34.9) | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Farmer | 1231 (40.8) | 1328 (44.0) | 1097 (36.0) | 728 (24.0) | <.001 |

| Worker | 333 (11.0) | 304 (10.1) | 382 (12.6) | 441 (14.5) | |

| Unemployed | 819 (27.2) | 721 (23.9) | 719 (23.6) | 790 (26.0) | |

| Other | 631 (20.9) | 668 (22.1) | 845 (27.8) | 1076 (35.5) | |

| Education | |||||

| Illiteracy | 684 (22.8) | 644 (21.6) | 517 (17.2) | 369 (12.2) | <.001 |

| Primary school | 604 (20.2) | 637 (21.4) | 599 (19.9) | 503 (16.6) | |

| Middle school | 1021 (34.1) | 995 (33.4) | 992 (33.0) | 1008 (33.3) | |

| ≥High school | 685 (22.9) | 705 (23.6) | 902 (30.0) | 1143 (37.8) | |

| Self-report diabetes | 35 (1.2) | 35 (1.2) | 37 (1.2) | 47 (1.6) | .47 |

| Dietary intake | |||||

| Energy, mean (SD), Kcal/d | 2276.2 (578.7) | 2162.7 (519.8) | 2120.6 (485.7) | 2207.0 (566.2) | <.001 |

| Fat, mean (SD), g/d | 75.6 (32.6) | 69.5 (28.7) | 72.7 (27.1) | 80.9 (30.4) | <.001 |

| Carbohydrate, mean (SD), g/d | 334.9 (110.4) | 321.8 (101.3) | 301.1 (94.4) | 292.7 (100.7) | <.001 |

| Protein, mean (SD), g/d | 64.1 (18.7) | 62.6 (17.1) | 65.4 (15.8) | 77.0 (24.5) | <.001 |

| Sodium, mean (SD), g/d | 5.5 (3.3) | 5.0 (3.1) | 4.7 (2.6) | 4.9 (3.0) | <.001 |

| Potassium, mean (SD), g/d | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.9 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Na:K ratio | 3.8 (2.5) | 3.3 (2.1) | 3.0 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.8) | <.001 |

| Vegetables, mean (SD), g/d | 329.0 (138.1) | 361.3 (138.4) | 385.9 (144.4) | 418.9 (185.3) | <.001 |

| Fruit intake | 1201 (39.2) | 1354 (44.2) | 1510 (49.3) | 1543 (50.4) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); Na:K, sodium to potassium.

SI conversion factor: To convert niacin to μmol/d, multiply by 8.123.

Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and New-Onset Hypertension

During a median (IQR) follow-up of 6.1 years (3.6-11.3 years), 4306 (45.0 per 1000 person-years) participants developed new-onset hypertension. Of these, 834 (19.4%) were diagnosed with hypertension by a physician, 533 (12.4%) reported use of antihypertensive treatment during follow-up, and 3955 (91.8%) had a new-onset mean SBP of 140 mm Hg or greater and/or a mean DBP of 90 mm Hg or greater during follow-up. Some of the patients met at least 2 of the 3 criteria.

Overall, the association between dietary niacin and new-onset hypertension followed a J-shape (Figure 1). Accordingly, when dietary niacin intake was assessed in quartiles and compared with quartile 1 (<12.4 mg/d), the risk of new-onset hypertension was lower for quartile 2 (12.4 to <14.3 mg/d: HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-0.97; P = .01), quartile 3 (14.3 to <16.7 mg/d: HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.64-0.76; P < .001), and quartile 4 (≥16.7 mg/d: HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-1.00; P = .05) (Table 2). The lowest risk of new-onset hypertension was found in those in quartile 3. When combining quartiles in further exploratory analysis, a significantly higher risk of new-onset hypertension was found among participants in quartiles 1 and 2 (<14.3 mg/d: adjusted HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.09-1.28; P < .001) and in quartile 4 (≥16.7 mg/d: adjusted HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.20-1.44) compared with those in quartile 3 (14.3 to <16.7 mg/d) (Table 2).

Figure 1. Dietary Niacin Intake and the Risk of New-Onset Hypertension.

The shaded area indicates 95% confidence intervals for adjusted hazard ratios (HR). The model was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, region, education, and occupation, as well as energy intake and sodium to potassium intake ratio.

Table 2. Dietary Niacin Intake and the Risk of New-Onset Hypertension Stratified by Quartiles and Combined Quartiles.

| Niacin intake, mg/d | Participants, No. | Events, No. (rate)a | Crude model | Adjusted modelb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Quartiles | ||||||

| Q1 (<12.4) | 3061 | 1188 (51.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Q2 (12.4 to <14.3) | 3060 | 1166 (46.6) | 0.90 (0.83-0.97) | .009 | 0.95 (0.87-1.04) | .27 |

| Q3 (14.3 to <16.7) | 3061 | 952 (36.2) | 0.70 (0.64-0.76) | <.001 | 0.83 (0.75-0.90) | <.001 |

| Q4 (≥16.7) | 3061 | 998 (47.0) | 0.92 (0.85-1.00) | .05 | 1.08 (0.99-1.19) | .09 |

| Categories | ||||||

| Q1-2 (<14.3) | 6121 | 2354 (49.0) | 1.36 (1.26-1.47) | <.001 | 1.18 (1.09-1.28) | <.001 |

| Q3 (14.3 to <16.7) | 3061 | 952 (36.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Q4 (≥16.7) | 3061 | 998 (47.0) | 1.32 (1.21-1.44) | <.001 | 1.31 (1.20-1.44) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; Q, quartile.

SI conversion factor: To convert niacin to μmol/d, multiply by 8.123.

Incident rate is presented per 1000 person-years of follow-up.

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, region, education, and occupation, as well as energy intake and sodium to potassium intake ratio.

Consistently in the threshold analysis, for every 1 mg/d increase in dietary niacin there was a 2% decrease in new-onset hypertension (adjusted HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00) in participants with dietary niacin less than 15.6 mg/d, and a 3% increase in new-onset hypertension (adjusted HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.04) in participants with dietary niacin 15.6 mg/d or greater (Table 3).

Table 3. Threshold Analyses of Dietary Niacin Intake on New-Onset Hypertension Using 2-Piecewise Regression Models.

| Niacin intake, mg/d | Crude model | Niacin intake, mg/d | Adjusted modela | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| <16.0 | 0.95 (0.93-0.96) | <.001 | <15.6 | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | .04 |

| ≥16.0 | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | <.001 | ≥15.6 | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

SI conversion factor: To convert niacin to μmol/d, multiply by 8.123.

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, region, education, and occupation, as well as energy intake and sodium to potassium intake ratio.

Moreover, further adjustments for waist to hip ratio, drinking status, sodium, and fruit and vegetable intake (eTable 2 in the Supplement), or excluding participants from the 3 autonomous cities (eTable 3 in the Supplement) did not substantially alter the association between dietary niacin and new-onset hypertension. Similar trends were also found for different components of new-onset hypertension, including hypertension diagnosed by a physician and participants who were using antihypertensive treatment during follow-up, and participants with mean SBP 140 mm Hg or greater and/or mean DBP of 90 mm Hg or greater during follow-up (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Stratified Analyses by Additional Factors

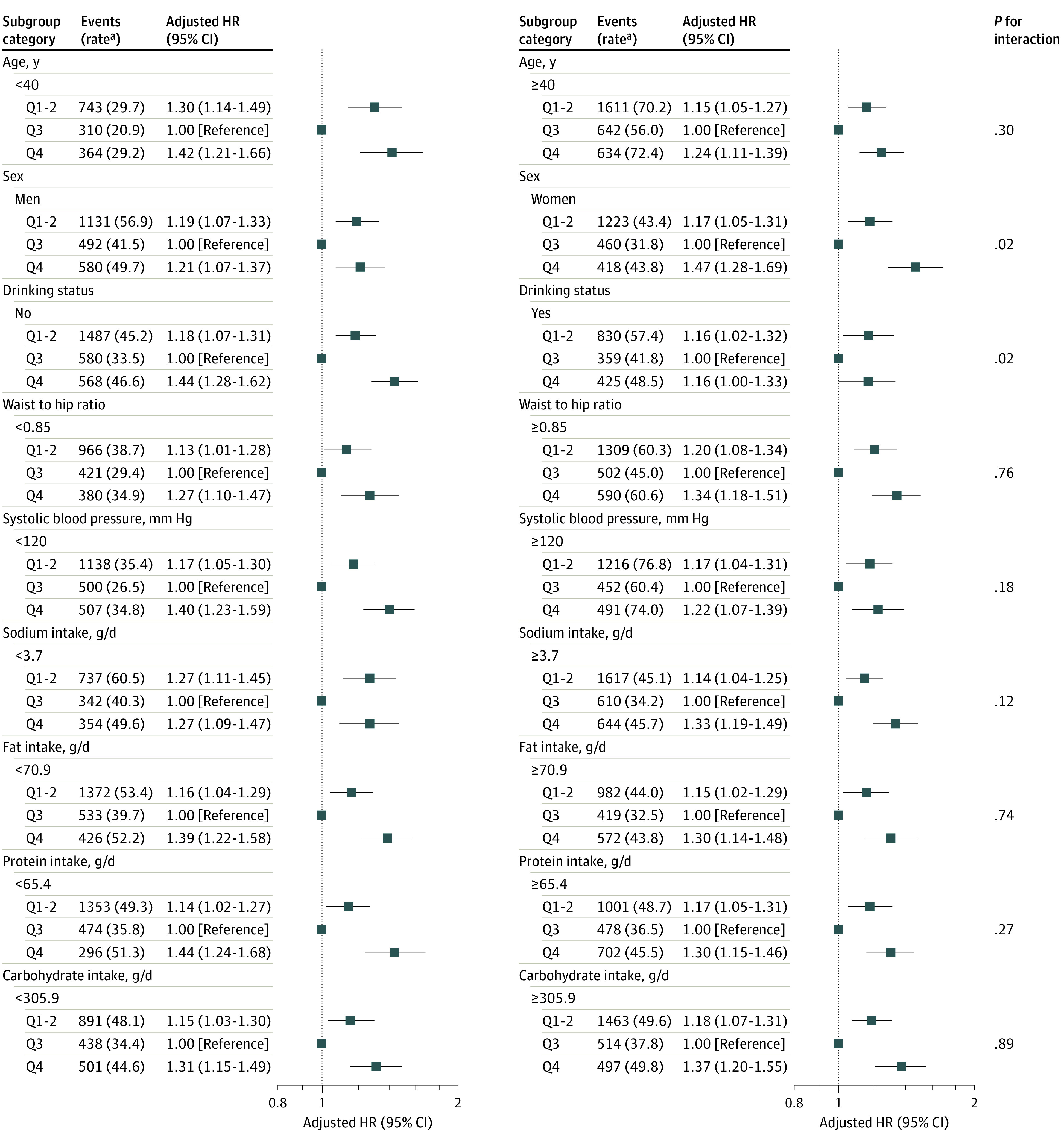

We performed further stratified analyses to assess the association between dietary niacin (quartile 1-2 vs quartile 3 vs quartile 4) and the risk of new-onset hypertension in various subgroups (Figure 2; eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Overall, the J-shaped association between dietary niacin intake and new-onset hypertension was observed in all subgroups.

Figure 2. Stratified Analyses by Potential Modifiers of the Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and New-Onset Hypertension.

aIncident rate is presented per 1000 person-years of follow-up.

The model was adjusted, if not stratified, for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, region, education, and occupation, as well as energy intake and sodium to potassium intake ratio.

None of the variables, including age, sex, BMI, waist/hip ratio, smoking status, drinking status, SBP, sodium to potassium intake ratio, potassium, sodium, fat, protein, carbohydrate, energy, fruit and vegetable intake, residence, and education level significantly modified the association between dietary niacin and new-onset hypertension (Figure 2; eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Although the P values for interactions for sex, drinking status, and vegetable intake were lower than .05, these results may not have significant clinical implications given multiple testing and similar directionality of the associations (Figure 2; eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this large, national, longitudinal cohort study among general Chinese adults, we found a J-shaped association between dietary niacin intake and new-onset hypertension, with an inflection point at approximately 15.6 mg/d and minimal risk at 14.3 to 16.7 mg/d of dietary niacin.

The acute and chronic effects of niacin on blood pressure have been evaluated in several previous trials, which have reported inconsistent results.10,11,12,13,14,15 The original Coronary Drug Project revealed that no significant changes in BP were found in men with previous myocardial infarction over 5 to 8.5 years of niacin treatment (3.0 g/d).10 However, a post hoc analysis of the data in patients with metabolic syndrome found that treatment with niacin was associated with a reduction in BP of approximately 2 to 3 mm Hg compared with placebo at treatment year 1.11 At the same time, Kelly et al14 found that short-term niacin treatment (ie, 500 mg daily for 7 days, then 1 g daily for a further 7 days) did not significantly affect SBP or DBP. An 8-week niacin titration (1 g/d for 4 weeks, 2g/d for the remaining 4 weeks) study of 412 dyslipidemic patients also showed no significant change in BP from baseline.12 Nevertheless, Gadegbeku et al15 reported that acute niacin administration (1.4 g infusion for 60 min) may lower BP in patients with hypertension, but not in normotensive patients. Data from a longer and larger (ie, 24 wk with 1613 participants) study suggested that, compared with placebo, niacin therapy (1 g/d for 4 weeks, then 2 g/d for 20 weeks) in patients with dyslipidemia significantly decreased BP at both 4 and 24 weeks.13 Overall, these studies indicated that the association between niacin supplementation and BP remains uncertain. Of note, all of these studies focused on relatively high levels of niacin supplementation and did not have detailed information about dietary niacin intake. Although it is reported that nutrients obtained from foods and supplements may confer different health effects,24 to date the association between dietary niacin intake and hypertension has not been thoroughly investigated. The CHNS study provides an opportunity to evaluate the dose-response association between dietary niacin intake and the risk of new-onset hypertension in the general population, with comprehensive adjustments for a number of known covariables and a series of subgroup analyses.

Our study provides some new insights. First, among participants with dietary niacin of less than 15.6 mg/d, the risk of new-onset hypertension significantly decreased with the increment of dietary niacin intake. Niacin has been widely used clinically to regulate abnormalities in lipid/lipoprotein metabolism. Some studies have found that niacin alone or in combination can slow or reverse the progression of atherosclerosis in patients with hypercholesterolemia.25,26 Endothelial dysfunction is considered to be the initial phase in the development of arterial hypertension and atherosclerosis.27 Niacin has been shown to promote the production of endothelial nitric oxide, increase vasodilation, and improve endothelial dysfunction.28,29 Moreover, niacin also reduces endothelial oxidative stress via increasing the cellular content of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reducing glutathione, and inhibiting reactive oxygen species generation in endothelial cells.30,31 Additionally, niacin can reduce the release of inflammatory markers such as lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and high sensitivity C-reactive protein.32,33 Taken together, a plausible biological explanation for the niacin-hypertension association we observed may be that niacin can regulate abnormal lipid metabolism, improve endothelial function, and has potentially antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.7 However, further research on this mechanism is needed.

Second, the risk of new-onset hypertension significantly increased with the increment of dietary niacin intake in participants with dietary niacin of 15.6 mg/d or greater. Elevated HCY and insulin resistance may impair endothelial function and are identified as important risk factors for hypertension.34,35 It was reported that an increased nicotinamide load resulted in a significant increase in pulse pressure, which might be related to the fact that high niacin intake depletes the methyl pool, increases HCY generation and betaine consumption, and inhibits catecholamine degradation.9,36 In addition, a previous study found that treatment with niacin was related to increased insulin resistance as well.14

Of note, Table 1 shows that participants with lower dietary niacin (quartile 1 and 2) were older and had higher SBP and DBP levels, lower percentages of residence in urban and southern regions, and a higher sodium to potassium intake ratio. All these variables may partly explain the increased hypertension risk in participants with lower dietary niacin in the crude model in Table 2. As expected, with the increase of these variables in the adjusted models, the HR (ie, quartile 1-2 vs quartile 3) decreased gradually. We speculated that the change between the crude and adjusted models may be in part accounted for by the joint effect of these baseline characteristics. However, our results should be further confirmed in more studies.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, because this is an observational analysis, residual confounding cannot be completely eliminated, although data were adjusted for a series of confounders. Second, the biosynthesis of niacin from tryptophan was not included in our analysis. In general, 60 mg of tryptophan is equivalent to 1 mg of niacin through de novo synthesis.37 Nevertheless, this biosynthesis process does not occur in all tissues.38 In our stratified analysis, protein intake did not significantly modify the association between dietary niacin intake and new-onset hypertension. Third, we have no detailed information on dietary supplement use. However, data from the 2010–2012 China Nutrition and Health Surveillance study, a nationally representative cross-sectional study covering all 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, showed that only 0.71%, 0.06%, and 0.2% of the Chinese population reported using nutrient supplements, multivitamins, and vitamin B supplements, respectively.39 Because of the low proportion of nutrient supplementation, especially vitamin B, we speculate that our findings may not be substantially changed by dietary supplement use. Fourth, because only 53 participants reported the use of special dietary patterns for the treatment of diabetes, and we lack information on circulating cholesterol levels in the present study, we could not examine the modifying effect of different dietary patterns and hypercholesterolemia. Other information was limited in our data source; the CHNS did not include clinic-based blood pressure measurements, and although the CHNS took place in different provinces and municipal cities that vary substantially in geography, economic development, public resources, and health indicators, the study participants could not represent the population of provinces or cities that were not included in the survey. Fifth, compared with those not included in the analysis, participants included seemed to be older and have a lower education level. However, all these variables were included in the regression models, and the stratified analysis further showed that age and education level did not materially modify the results. Sixth, our study was conducted among Chinese living in China—whether the observed findings can be extrapolated to other populations needs further investigation. Therefore, our results should be regarded as hypothesis generating. Further confirmation of our findings in more studies is essential.

Conclusions

In summary, our study found a J-shaped association between dietary niacin intake and new-onset hypertension in the general population of Chinese adults, with an inflection point at about 15.6 mg/d and minimal risk observed at 14.3 to 16.7 mg/d of dietary niacin. If further confirmed, our data provide evidence for maintaining the optimal dietary niacin intake levels for the primary prevention of hypertension.

eFigure 1. Flow Chart of the Participants

eFigure 2. Stratified Analyses by Potential Effect Modifiers for the Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake (Quartile 1-2 vs. Quartile 3 vs. Quartile 4) and New-Onset Hypertension

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Included and Excluded Participants

eTable 2. The Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and the Risk of New-Onset Hypertension With Further Adjustment for Waist/Hip Ratio, Drinking Status, Sodium, Fruits and Vegetables Intake

eTable 3. The Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and the Risk of New-Onset Hypertension With Exclusion of Participants From the Three Autonomous Cities

eTable 4. The Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and Different Components of New-Onset Hypertension

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1923-1994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Zhou H, Liu M, et al. Association of visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure and first stroke risk in hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease. J Hypertens. 2020;38(4):610-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin X, Huo Y. H-Type hypertension, stroke and diabetes in China: opportunities for primary prevention. J Diabetes. 2016;8(1):38-40. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewington S, Lacey B, Clarke R, et al. ; China Kadoorie Biobank Consortium . The burden of hypertension and associated risk for cardiovascular mortality in China. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):524-532. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Yang L, Wang L, et al. Burden of hypertension in China: a nationally representative survey of 174 621 adults. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:516-523. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkland JB. Niacin status, NAD distribution and ADP-ribose metabolism. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(1):3-11. doi: 10.2174/138161209787185823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeman M, Vecka M, Perlík F, et al. Pleiotropic effects of niacin: current possibilities for its clinical use. Acta Pharm. 2016;66(4):449-469. doi: 10.1515/acph-2016-0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poynten AM, Gan SK, Kriketos AD, et al. Nicotinic acid-induced insulin resistance is related to increased circulating fatty acids and fat oxidation but not muscle lipid content. Metabolism. 2003;52(6):699-704. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(03)00030-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun WP, Li D, Lun YZ, et al. Excess nicotinamide inhibits methylation-mediated degradation of catecholamines in normotensives and hypertensives. Hypertens Res. 2012;35(2):180-185. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coronary Drug Project Research Group Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231(4):360-381. doi: 10.1001/jama.1975.03240160024021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canner PL, Furberg CD, McGovern ME. Benefits of niacin in patients with versus without the metabolic syndrome and healed myocardial infarction (from the Coronary Drug Project). Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(4):477-479. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.08.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paolini JF, Mitchel YB, Reyes R, et al. Effects of laropiprant on nicotinic acid-induced flushing in patients with dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(5):625-630. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bays HE, Maccubbin D, Meehan AG, Kuznetsova O, Mitchel YB, Paolini JF. Blood pressure-lowering effects of extended-release niacin alone and extended-release niacin/laropiprant combination: a post hoc analysis of a 24-week, placebo-controlled trial in dyslipidemic patients. Clin Ther. 2009;31(1):115-122. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly JJ, Lawson JA, Campbell LV, et al. Effects of nicotinic acid on insulin sensitivity and blood pressure in healthy subjects. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14(9):567-572. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gadegbeku CA, Dhandayuthapani A, Shrayyef MZ, Egan BM. Hemodynamic effects of nicotinic acid infusion in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16(1):67-71. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(02)03196-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Zhang B, Wang HJ, et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with dietary intake of thiamine, riboflavin, and niacin among Chinese adults in 2015. Biomed Environ Sci. 2020;33(9):660-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popkin BM, Du S, Zhai F, Zhang B. Cohort profile: the China Health and Nutrition Survey—monitoring and understanding socioeconomic and health change in China, 1989-2011. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(6):1435-1440. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Wang DD, Ley SH, et al. Time trends of dietary and lifestyle factors and their potential impact on diabetes burden in China. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(12):1685-1694. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin B, Viera AJ, Muntner P, et al. Visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure is related to late-life cognitive decline. Hypertension. 2016;68(1):106-113. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang B, Zhai FY, Du SF, Popkin BM. The China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1989-2011. Obes Rev. 2014;15(suppl 1):2-7. doi: 10.1111/obr.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.China Health and Nutrition Survey. UNC Carolina Population project Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/china

- 22.Zhai F, Guo X, Popkin B, et al. Evaluation of the 24-hour individual recall method in China. Food Nutr Bull. 1996;17 (2): 1-7. doi: 10.1177/156482659601700209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willett W, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(1):17-27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang FF, Barr SI, McNulty H, Li D, Blumberg JB. Health effects of vitamin and mineral supplements. BMJ. 2020;369:m2511. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers CD, Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Niacin therapy in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15(6):659-665. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200412000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown BG, Zhao XQ, Chait A, et al. Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(22):1583-1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen B, Lu Y, Chen Y, Cheng J. The role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress-induced endothelial injuries. J Endocrinol. 2015;225(3):R83-R99. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahebkar A. Effect of niacin on endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Vasc Med. 2014;19(1):54-66. doi: 10.1177/1358863X13515766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu BJ, Yan L, Charlton F, Witting P, Barter PJ, Rye KA. Evidence that niacin inhibits acute vascular inflammation and improves endothelial dysfunction independent of changes in plasma lipids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(5):968-975. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganji SH, Qin S, Zhang L, Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Niacin inhibits vascular oxidative stress, redox-sensitive genes, and monocyte adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202(1):68-75. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamoud S, Kaplan M, Meilin E, et al. Niacin administration significantly reduces oxidative stress in patients with hypercholesterolemia and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345(3):195-199. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182548c28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thoenes M, Oguchi A, Nagamia S, et al. The effects of extended-release niacin on carotid intimal media thickness, endothelial function and inflammatory markers in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(11):1942-1948. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuvin JT, Dave DM, Sliney KA, et al. Effects of extended-release niacin on lipoprotein particle size, distribution, and inflammatory markers in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(6):743-745. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao M, Wang X, He M, et al. Homocysteine and stroke risk: modifying effect of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and folic acid intervention. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1183-1190. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Maio R, et al. Endothelial dysfunction, ADMA and insulin resistance in essential hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142(3):236-241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun WP, Zhai MZ, Li D, et al. Comparison of the effects of nicotinic acid and nicotinamide degradation on plasma betaine and choline levels. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(4):1136-1142. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deen CPJ, van der Veen A, van Faassen M, et al. Urinary excretion of N1-methylnicotinamide, as a biomarker of niacin status, and mortality in renal transplant recipients. J Clin Med. 2019;8(11):1948. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogan KL, Brenner C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:115-130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong W, Liu A, Yao Y, et al. Nutrient supplement use among the Chinese population: a cross-sectional study of the 2010-2012 China Nutrition and Health Surveillance. Nutrients. 2018; 10: 1733. doi: 10.3390/nu10111733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flow Chart of the Participants

eFigure 2. Stratified Analyses by Potential Effect Modifiers for the Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake (Quartile 1-2 vs. Quartile 3 vs. Quartile 4) and New-Onset Hypertension

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Included and Excluded Participants

eTable 2. The Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and the Risk of New-Onset Hypertension With Further Adjustment for Waist/Hip Ratio, Drinking Status, Sodium, Fruits and Vegetables Intake

eTable 3. The Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and the Risk of New-Onset Hypertension With Exclusion of Participants From the Three Autonomous Cities

eTable 4. The Association Between Dietary Niacin Intake and Different Components of New-Onset Hypertension