Abstract

Introduction

The definitive diagnosis of neurocysticercosis continues to be challenging. We evaluate the role of newer magnetic resonance imaging techniques including constructive interference in steady state, susceptibility-weighted imaging, arterial spin labelling and magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis.

Aims and objectives

To study the utility of newer magnetic resonance imaging sequences in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis.

Patients and methods

Eighty-five consecutive patients with neurocysticercosis attending a tertiary care hospital and teaching centre in northern India were included in the study. The diagnosis of neurocysticercosis was made by the Del Brutto criteria. All patients received treatment according to standard guidelines and were followed at 3-month intervals. The following magnetic resonance sequences were performed at baseline: T1 and T2-weighted axial sequences; T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery axial sequences; diffusion-weighted imaging; susceptibility-weighted imaging; pre and post-contrast T1-weighted imaging; heavily T2-weighted thin sections (constructive interference in steady state); arterial spin labelling (n = 19); and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (n = 24).

Results

The mean (±SD) age was 29.4 ± 12.9 years and 76.5% were men. Seizures were the commonest symptom (89.4%) followed by headache (24.3%), encephalitis (9.4%) and raised intracranial pressure (9.4%). Scolex could be visualised in 43.7%, 55.5% and 61.2% of neurocysticercosis patients using conventional, susceptibility-weighted angiography and constructive interference in steady state imaging sequences, respectively. Susceptibility-weighted angiography and constructive interference in steady state images resulted in significantly higher (P < 0.01) visualisation of scolex compared to conventional sequences.

Conclusion

Newer magnetic resonance imaging modalities have a lot of promise for improving the radiological diagnosis of neurocysticercosis.

Keywords: Neurocysticercosis, conventional MRI, CISS, SWAN

Introduction

Neurocysticercosis continues to account for one-third of all epilepsy patients in developing countries including India.1–3 The diagnosis of neurocysticercosis is based on neuroimaging, either a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan or gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain.4 An inherent difficulty in radiological diagnosis is the remarkable heterogeneity of findings of neurocysticercosis in terms of number, size, character and location of cysts. Thus, conventional gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the brain often fails to provide a definitive diagnosis of neurocysticercosis.

Recently, new MRI techniques such as constructive interference in steady state (CISS) 3D, susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) and arterial spin labelling (ASL) have raised hopes of the better differentiation of neurocysticercosis from other causes of ring-enhancing lesions.5 Thus, we planned this prospective observational study to delineate the role of newer MRI sequences in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis.

Objectives

To study the sensitivity of newer MRI sequences including CISS 3D, SWI and ASL in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis in addition to conventional MRI sequences.

Patients and methods

This prospective observational study included 85 consecutive patients with neurocysticercosis attending a tertiary care hospital and teaching centre in northern India. The study period was from January 2016 to June 2017. The diagnosis of neurocysticercosis was made according to Del Brutto’s criteria.6 The patients were included irrespective of clinical manifestations of neurocysticercosis or treatment taken. All patients were treated and followed at 3-monthly intervals according to the consensus guidelines.7 Albendazole was used at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day for 10 days except in patients with contraindications to its use, along with corticosteroids. All cases underwent gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the brain at baseline. The following magnetic resonance sequences were carried out in all the patients: (a) T2-weighted axial sequences; (b) T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) axial sequences; (c) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI); (d) SWI; (e) pre and post-contrast T1-weighted imaging; (f) heavily T2-weighted thin sections (CISS); (g) ASL (n = 19); and (h) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) (n = 24). The magnetic resonance images were reviewed by a neuroradiology consultant (CKA) with 10 years’ experience. Only patients with ring-enhancing lesions (RELs) were included; that is, suspected neurocysticercosis in the vesicular, colloidal vesicular and granular nodular stages. MRI showing only calcified lesions was not included. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants before inclusion in the study.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS version 23.0. Measures of central tendency (mean and median) were calculated for all quantitative variables along with measures of dispersion (standard deviation (SD) and standard error). Qualitative variables were described as frequencies and proportions. Proportions were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, whichever was applicable. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographic profile

Mean ± SD age in the current study was 29.4 ± 12.9 years. Only two (2.3%) patients were over 60 years of age. The study group consisted of 65 (76.5%) men and 20 (23.5%) women. Seizures were the commonest symptom at presentation, seen in 76 (89.4%) patients followed by headache (n = 21, 24.7%), encephalitis (n = 8, 9.4%) and raised intracranial pressure (ICP) (n = 8, 9.4%). These as well as other clinical features are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the study group.

| Parameter | Value (n=85) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (±SD) age in years | 29.4 ± 12.9 | ||||

| (Age >60 years; n = 2) | |||||

| Male sex | 65 (76.5%) | ||||

| Symptom at presentation (n = 85) | |||||

| Seizures (GTCS-51, SPS-10; PGTCS-9; CPS-6) | 76 (89.4%) | ||||

| Encephalitis | 8 (9.4%) | ||||

| Cranial nerve involvement | 1 (1.2%) | ||||

| Headache | 21 (24.7%) | ||||

| Focal neurological deficits | 3 (3.5%) | ||||

| Raised intracranial pressure | 8 (9.4%) | ||||

| Drugs received | |||||

| AED (CBZ-63, LEV-22, CLB-23, PHT-3, PB-2, VPA-6; more than one AED 32) | 76 (89.4%) | ||||

| Steroids (oral + intravenous) | 82 (96.5%) | ||||

| Albendazole | 59 (69.4%) | ||||

| Methotrexate | 15 (17.6%) | ||||

| Clinical improvement at follow-up (n = 83) | |||||

| Improvement seen | 67 (80.7%) | ||||

| No improvement seen | 16 (19.3%) | ||||

| Taenia solium-related investigations | |||||

| Stool toutine for T solium ova/cyst (n = 85) | 0 | ||||

| Positive serum ELISA for cysticercal antibodies (n = 81) | 20 (24.7%) | ||||

| Influence of number of cysts on ELISA positivity | |||||

|

Number of cysts |

P value |

||||

|

Parameter |

1 |

2–10 |

11–50 |

>50 |

<0.0001 |

| Number of Patients | 37 | 15 | 10 | 19 | |

| ELISA positivity | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (89%) | |

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; SPS: simple partial seizures; GTCS: generalised tonic clonic seizures; PGTCS: partial with secondary generalised tonic clonic seizures; CPS: complex partial seizures; AED: antiepileptic drug; CBZ: carbamazepine; LEV: levetiracetam; CLB: clobazam; PHT: phenytoin; PB: phenobarbitone; VPA: valproate.

Management outcomes

Antiepileptic drugs were given in 89.4% (n = 76) of the patients (Table 1). Steroids either oral or intravenous were given in 96.5% (n = 82) of patients. Albendazole was given in a dose of 15 mg/kg daily for 10 days in all the patients (n = 59; 69.4%) except when it was contraindicated (n = 26; 24 >100 cysts in the brain; four intraocular cysts, two had both); 17.6% (n = 15) of patients had to be started on steroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate due to persistent inflammation.

Clinical improvement defined as the resolution of the presenting symptoms was seen in 80.7% (n = 67) and persistence of symptoms was seen in 19.3% (n = 16) of patients (Table 1).

MRI characteristics

Number of lesions: 39 (45.8%) patients had a single cyst, 13 (17.6%) had 2 to 10 cysts, 12 (14.1%) had 10–50 cysts while 19 (22.3%) patients had more than 50 cysts. The mean size of cyst (n = 80) was 5 mm or less in four (5%) patients, 6–10 mm in 49 (61.3%), 11–15 mm in 22 (27.5%) and 16–20 mm in three (3.8%) patients. Only two (2.4%) patients had a cyst size greater than 2 cm. The commonest site of neurocysticercosis was frontal lobe (71.8%) followed by parietal lobe (55.3%), temporal lobe (40%), occipital lobe (36.5%), thalamus (22.4%), basal ganglia (22.4%) and cerebellum (20%). Subarachnoid involvement (racemose forms) was seen in nine (10.6%) while hydrocephalus was observed in seven (8.2%) patients. Perilesional oedema was seen in 92.9% of patients. It was minimal in 15.7%, mild (within 2 cm) in 61.7%, gross (>2 cm but less than two lobes) in 14% and severe (more than two lobes) in two (2.4%) patients. Calcification was seen in 57.6% and some evidence of diffusion restriction was seen in 16.5% of patients. The MRI findings at presentation and follow-up have been highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging data of study population at presentation and follow-up.

| Number of cysticercal lesions | At presentation (n = 85) | At follow-up (n = 58) |

|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| 0 | None | 7 (10.2) |

| 1 | 39 (45.8) | 24 (40.7) |

| 2–10 | 15 (17.6) | 7 (11.9) |

| 11–50 | 12 (14.1) | 6 (10.2) |

| >50 | 19 (22.3) | 15 (25.4) |

|

Size of the cyst in mm | ||

| Size of the cyst | ||

| 0 | None | 7 (12.5) |

| 5 or less | 4 (5) | 4 (7.1) |

| 6–10 | 49 (61.3) | 37 (63.8) |

| 11–15 | 22 (27.5) | 9 (16.1) |

| 16–20 | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| 21–25 | 2 (2.5) | None |

|

Other magnetic resonance imaging findings | ||

| Finding | ||

| Presence of contrast enhancement | 82 (96.4) | 45 (77.6) |

| Perilesional oedema | 79 (92.9) | 31 (53.3) |

| Minimal rim of oedema | 13 (15.7) | 11 (19) |

| Mild rim of oedema (within 2 cm) | 52 (61.2) | 19 (32.8) |

| Gross oedema (beyond 2 cm but <2 lobes) | 12 (14.1) | 1 (1.7) |

| Oedema with hemisphere involved (>2 lobes) | 2 (2.4) | Nil |

| Presence of calcification | 49 (57.6) | 35 (60.3) |

| Presence of diffusion restriction | 14 (16.5) | NA |

| Magnetic resonance spectroscopy data (n = 25) | ||

| Choline/creatinine ratio <2 | 23 (96) | NA |

| Choline/NAA ratio <2 | 23 (96) | |

| Lipid lactate peak | 3 (12.5) | |

| Lactate peak | 2 (8.3) | |

| Alanine/succinate/pyruvate peaks | 0 | |

| Arterial spin labelling data | ||

| Hypoperfusion | 12 (63.2) | NA |

| Isoperfusion | 7 (36.8) | |

| Hyperperfusion | 0 | |

Visualisation of scolex with CISS and SWAN sequences and MRS and ASL observations

In the current study 80 patients underwent both conventional as well as newer MRI sequences (steady state acquisition (CISS) and susceptibility-weighted angiography (SWAN) sequences). Scolex could be visualised in 43.7%, 55.5% and 61.2% of neurocysticercosis patients using conventional, SWAN and CISS imaging sequences, respectively. When compared, both SWAN and CISS images (Table 3) resulted in significantly higher (P < 0.01) visualisation of scolex compared to conventional sequences. MRS sequences could be applied in 24 patients. Twenty-three (96%) patients had choline/creatine and choline/N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) ratios less than 2. Two (8.33%) patients had small lactate peaks while three (12.5%) had lipid lactate peaks, but all patients had morphology of neurocysticercosis. Alanine, succinate and pyruvate were not observed in any patient. Interpretable ASL sequences could be performed in 19 patients. Twelve (63.2%) patients had hypoperfusion and seven (36.8%) patients had isoperfusion.

Table 3.

Comparison of visualisation of scolex on conventional and SWAN and CISS magnetic resonance sequences.

| Visualisation of scolex | Conventional imaging sequences | SWAN sequences | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seen | 35 | 44 | <0.01 |

| Not seen | 45 | 36 | |

| CISS sequences | |||

| Seen | 35 | 49 | <0.01 |

| Not seen | 45 | 31 |

CISS: constructive interference in steady state; SWAN: susceptibility-weighted angiography.

Radiological resolution

In the current study, 58 patients underwent repeat MRI at follow-up. Out of these, 24 (41.4%) showed improvement in imaging findings including partial (n = 17; 29.3%) as well as complete (n = 7, 12.1%) resolution of cysts. In total, 34 (58.6%) patients did not reveal any change in radiological status (Table 4).

Table 4.

Influence of various clinical and radiological factors on radiological resolution (n = 58).

| Improvement in follow-up MRI | No improvement in follow-up MRI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 24) | (n = 34) | ||

| Seizures | |||

| Simple partial seizures | 05 | 2 | 0.14 |

| Complex partial seizures | 04 | 1 | 0.16 |

| Partial with secondary generalisation | 02 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Generalised tonic clonic | 13 | 19 | 0.58 |

| Presence of encephalitis | 00 | 6 | 0.037 |

| Cranial nerve involvement | 00 | 0 | – |

| Presence of headache | 04 | 11 | 0.226 |

| Presence of focal neurological deficits | 00 | 2 | 0.50 |

| Presence of raised ICP | 01 | 5 | 0.38 |

| Number of MRI lesions | |||

| 1 | 17 | 11 | <0.0001 |

| 2–10 | 07 | 3 | |

| 11–50 | 00 | 6 | |

| >50 | 00 | 14 | |

| Contrast enhancement on MRI | 24 | 32 | 0.50 |

| Presence of perilesional oedema | |||

| No oedema | 00 | 4 | 0.24 |

| Minimal oedema | 06 | 6 | |

| Mild oedema | 13 | 20 | |

| Gross oedema | 04 | 3 | |

| Hemispheric oedema | 01 | 0 | |

| Presence of calcification | 12 | 22 | 0.25 |

| Subarachnoid cysts | 00 | 6 | 0.03 |

| Intraventricular cysts | 00 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Extra CNS lesions | 00 | 8 | 0.01 |

| Hydrocephalus | 00 | 4 | 0.13 |

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; ICP: intracranial pressure; CNS: central nervous system.

Discussion

The mean age in the current study was 29.4 ± 12.9 years, with the majority (63.5%) of patients under 30 years of age. Thus, neurocysticercosis affects people in the prime of their age. The mean age in the current study is similar to other studies8–10 across the globe. The higher male to female ratio observed in the current study is also similar to that reported previously11,12 from the Indian subcontinent. The reason behind male predominance could be higher exposure to risk factors among men.

The clinical manifestations of neurocysticercosis are varied. Our patients had a myriad of symptoms including seizures, headache, focal neurological deficits in the form of paresis, ataxia and hearing loss, raised ICP and so on. These findings were also similar to those reported previously.13

Magnetic resonance characteristics

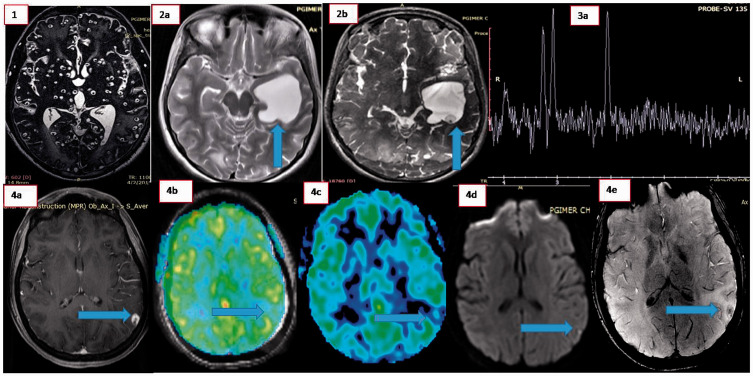

In the current study 39 patients (46%) had a single lesion and 46 (54%) had more than one lesion. A total of 19 patients (22%) had a severe disease burden (>50 lesions). This is in contrast to other studies,12,13 in which there was a much larger proportion of single lesions (94%). The most plausible reason for this difference could be a ‘referral bias’ due to the fact that ours is a tertiary care institute catering to patients with greater disease burden who are generally sicker and more difficult to manage than those with smaller disease burden as well as a shorter follow-up. The other characteristics of the lesions, including contrast enhancement, perilesional oedema and calcification, were in agreement with other studies.13-15 Some of the conventional imaging findings from our study are as highlighted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(1) Magnetic resonance imaging (constructive interference in steady state sequences) showing multiple neurocysticercosis. (2a) and (2b) Visualisation of scolex on constructive interference in steady state sequences (2b) while conventional T2-weighted imaging (2a) fails to reveal the same. (3a) Magnetic resonance spectroscopy showing lipid and lipid lactate peaks in a patient with neurocysticercosis. 4(a–c) Arterial spin labelling (ASL) in neurocysticercosis. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (4a) showing ring-enhancing lesion in left parietal region while ASL (4b) and superimposed T2-ASL (4c) images show relative hypoperfusion in the same region. (4d) Diffusion-weighted imaging showing evidence of diffusion restriction in scolex and (4e) evidence of blooming on susceptibility-weighted imaging in a patient with neurocysticercosis.

Role of advanced imaging techniques in diagnosis of neurocysticercosis

Tmhe current study documents clear superiority (P < 0.01) of 3D CISS and SWAN sequences in demonstrating scolex in neurocysticercosis lesions (61.2%% and 55.5%, respectively) compared to conventional sequences (43.7%). MRS sequences (n = 24) revealed choline/NAA ratios less than 2 in 96% of lesions signifying their benign nature. Five patients had small lactate peaks and lipid lactate peaks. Scolex could be visualised in all these patients confirming a diagnosis of neurocysticercosis. Thus, MRS alone cannot be used to diagnose a lesion as neurocysticercosis but can be used to support the existence of a benign lesion compared to a malignant lesion. The other findings of alanine, succinate, alanine and pyruvate peaks, which may be observed in racemose neurocysticercosis,15 were not seen in our cases. The reasons could be the relatively small size of the lesions leading to difficulty in voxel placement and reduced overall signal as well as less use of short TE sequences.

ASL (n = 19) revealed hypoperfusion in 12 (63.1%) and normal perfusion in seven (36.8%) patients. None of our cases had hyperperfusion, a property which may be used in differentiating neurocysticercosis from suspected malignant lesions. The likely reason for this observation is the fact that the parasite does not induce peripheral vascularity and inflammation sufficient to a degree to induce hyperperfusion.

Radiological follow-up

In the current study, overall improvement (complete resolution seven (12.1%) and partial improvement 17 (29.3%)) seen on radiological follow-up was less in comparison to other studies from eastern10 and southern India.15 The likely reason for these observations is: (a) a higher disease burden in the form of the number of lesions (27.5% and 16.1% rates of multiple lesions in previous studies (15 and 10, respectively) compared to the 51.7% rate of multiple lesions in the current study); and (b) the short duration of follow-up in the current study.

Finally, we conclude that advanced MRI techniques may increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing neurocysticercosis and hence may help in the avoidance of unnecessary diagnostic and therapeutic errors. Larger studies with greater sample sizes may help in establishing their role further.

Footnotes

Author contribution: Akash Batta: Collection and analysis of the data; Karthik Vinay Mahesh: Collection of data; Nandita Prabhat: Collection and analysis of data; Ritu Shree: Drafting and critical revision of manuscript; Manoj K Goyal: Analysis of data, writing of manuscript; Chirag K Ahuja: Collection of data, drafting of manuscript; Alex Rebello: Collection of data; Naresh Tandyala: Collection of data, statistical analysis; Abeer Goel: Collection of data, statistical analysis; Aditya Choudhary: Drafting the article, analysis of the data; manuscript preparation; Gunjan Goyal: Analysis and interpretation of the data; Manish Modi: Planning the study, supervision of study, revising the intellectual content, analysis or interpretation of the data; Paramjeet Singh: revision of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Karthik Vinay Mahesh https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7163-1190

Ritu Shree https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2437-5507

Manoj K Goyal https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7375-4215

References

- 1.Singh G, Bawa J, Chinna D, et al. Association between epilepsy and cysticercosis and toxocariasis: a population‐based case–control study in a slum in India. Epilepsia 2012; 53: 2203–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brutto OH, Santibáñez R, Idrovo L, et al. Epilepsy and neurocysticercosis in Atahualpa: a door‐to‐door survey in rural coastal Ecuador. Epilepsia 2005; 46: 583–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Brutto OH. Diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis, revisited. Pathogens Global Health 2012; 106: 299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Do Amaral LL, Ferreira RM, da Rocha AJ, et al. Neurocysticercosis: evaluation with advanced magnetic resonance techniques and atypical forms. Topics Magn Res Imag 2005; 16: 127–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soni N, Srindharan K, Kumar S, et al. Arterial spin labeling perfusion: prospective MR imaging in differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic intra-axial brain lesions. Neuroradiol J 2018; 31: 544–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia HH, Pretell EJ, Gilman RH, et al. A trial of antiparasitic treatment to reduce the rate of seizures due to cerebral cysticercosis. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García HH, Evans CAW, Nash TE, et al. Current consensus guidelines for treatment of neurocysticercosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15: 747–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpio A, Hauser WA. Prognosis for seizure recurrence in patients with newly diagnosed neurocysticercosis. Neurology 2002; 59: 1730–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaushal S, Rani A, Chopra SC, et al. Safety and efficacy of clobazam versus phenytoin-sodium in the antiepileptic drug treatment of solitary cysticercus granulomas. Neurol India 2006; 54: 157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharjee S, Biswas P, Mondal T. Clinical profile and follow-up of 51 pediatric neurocysticercosis cases: A study from Eastern India. Ann Ind Acad Neurol 2013; 16: 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raina SK, Razdan S, Pandita KK, et al. Active epilepsy as indicator of neurocysticercosis in rural northwest India. Epilepsy Res Treat 2012; 2012: article ID 802747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carabin H, Ndimubanzi PC, Budke CM, et al. Clinical manifestations associated with neurocysticercosis: a systematic review. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis 2011; 5: e1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patil TB, Paithankar MM. Clinico-radiological profile and treatment outcomes in neurocysticercosis: a study of 40 patients. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2010; 3: 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora BS, Dhamija K. Neurocysticercosis: clinical presentations, serology and radiological findings: experience in a teaching institution. Int J Res Med Sci 2016; 4: 519–523. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernández RD, Durán BB, Lujambio PS. Magnetic resonance imaging in neurocysticercosis. Top Magn Res Imag 2014; 23: 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]