Abstract

Chikungunya virus can be transmitted perinatally leading to serious neurological sequelae. We report the longitudinal evolution of the brain magnetic resonance imaging aspects of three cases of mother-to-child Chikungunya virus transmission. The first magnetic resonance imaging scan presented brain cavitations, with or without corpus callosum diffusion restriction. Follow-up scans showed reduction in the volume of cavitations, with resolution of the restricted diffusion. However, one patient presented with a normal brain magnetic resonance image, despite the delay in neurocognitive development.

Keywords: Chikungunya virus, perinatal transmission, brain MRI, encephalitis

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), whose transmission is primarily vector borne, has re-emerged as a public health threat in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas over the past 15 years.1,2 While less frequent than spread by mosquito vectors, CHIKV can also be transmitted from mother to child, usually during labour. Vertical transmission was first demonstrated during the 2005–2006 outbreak on Réunion Island, France, with a series of neonatal complications, including fever, irritability, hyperalgesia syndrome, limb oedema, cutaneous rashes, sepsis, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation and encephalitis, which can result in lifelong neurological consequences.3,4

Although lesions in brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of patients with neonatal encephalitis due to CHIKV have previously been described,5 a description of the long-term evolution of these findings is important for a better understanding of the longitudinal clinical evolution of the disease and is still lacking in the literature.

In this article, we describe the evolution of brain MRI findings in three cases of perinatal encephalitis due to CHIKV infection.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review board. All subjects’ legal guardians provided written informed consent for study participation.

Pregnant women were screened for CHIKV infection if they presented with typical symptoms during pregnancy, notably in the peripartum period. A diagnosis of maternal CHIKV infection was based on the presence of serum anti-CHIKV immunoglobulin M (IgM), performed by IgM antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Mac-ELISA), and/or serum detection of the viral genome by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR). The diagnosis of neonatal CHIKV infection was defined as the detection of anti-CHIKV IgM and/or the viral genome in serum or cerebrospinal fluid. The diagnosis of mother-to-child transmission was defined as CHIKV infection confirmed in the mother during the perinatal period as well as CHIKV infection diagnosed in her newborn during the first 21 days of life. All participants were also tested for Zika, dengue, toxoplasmosis, hepatitis B, cytomegalovirus, rubella, herpes, syphilis and HIV.

All brain MRIs were performed using a 1.5 Tesla scanner (Avanto or Aera; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The MRI protocol included sagittal T1-weighted images (repetition time (TR) 1400 ms; echo time (TE) 7.3 ms; field of view (FOV) 220 mm; matrix 320 × 60; section thickness 4 mm with a 20% gap; flip angle 150°), axial T1-weighted images (TR 464 ms; TE 17 ms; FOV 220 mm; matrix 256 × 60; section thickness 4 mm with a 20% gap; flip angle 90°); axial and coronal T2-weighted images (TR 3890 ms; TE 110 ms; FOV 220 mm; matrix 320 × 60; section thickness 4 mm with a 20% gap; flip angle 150°); axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (TR 9000 ms; TE 90 ms; FOV 220 mm; matrix 256 × 70; section thickness 4 mm with a 20% gap; flip angle 150°; inversion time 2500 ms), diffusion-weighted imaging (b0 0 and b1 1000 s/mm2; TR 5400 ms; TE 103 ms; FOV 210 mm; slices thickness 4 mm, with a 20% gap; EPI factor 163); phase encoding direction: anterior to posterior, with apparent diffusion coefficient map calculation; and axial T2*-weighted images (TR 520 ms; TE 26 ms; FOV 220 mm; matrix 320 × 60; section thickness 4 mm with a 20% gap; flip angle 20°).

Case reports

We performed longitudinal follow-up of brain MRIs in three neonates with perinatally acquired CHIKV infection. Each of the participants underwent two brain MRIs. All mothers reported characteristic symptoms of CHIKV infection in the peripartum period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and follow-up MRI characteristics of three patients with mother-to-child perinatal CHIKV encephalitis.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonate sex | Female | Female | Female |

| Gestational age at the onset of maternal symptoms | 36 weeks | 37 weeks | 38 weeks |

| Mother’s symptoms | Fever and disseminated cutaneous rash | Fever and arthralgia | Fever and cutaneous rash |

| CHIKV diagnosis method in the mother | Positive IgM for CHIKV in the blood | RT–PCR positive for CHIKV in the blood | RT–PCR positive for CHIKV in the blood |

| Delivery | Caesarean | Caesarean | Vaginal |

| Gestational age at birth | 36 Weeks | 38 Weeks | 38 Weeks |

| Neonate age at symptoms onset | 4 Days | 5 Days | 6 Days |

| Neonate age at first MRI | 17 Days | 30 Days | 25 Days |

| First MRI findings | Restricted diffusion in the entire corpus callosum, centrum semiovale and corona radiata cavitations, associated with subcortical lesions | Subcortical cavitations in the frontal and parietal lobes, suggestive of perivascular distribution, without restricted diffusion | Discrete focus of haemorrhage in the right parietal lobe, with normal myelination for age |

| Follow-up MRI findings (time interval between the MRIs) | Regressed restricted diffusion in the corpus callosum, the cavitations in the semioval centre and corona radiata had shrunk, the subcortical lesions resolved, and the lateral ventricles had increased (2.5 months) | Cavitations had shrunk, presenting with perilesional areas with hyperintensities on T2-weighted imaging and FLAIR (1 year and 4 months) | Persistence of the focus of haemorrhage. Cerebral myelination evolved normally (10 months) |

CHIKV: Chikungunya virus; FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; IgM: immunoglobulin M; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; RT–PCR: reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Case 1

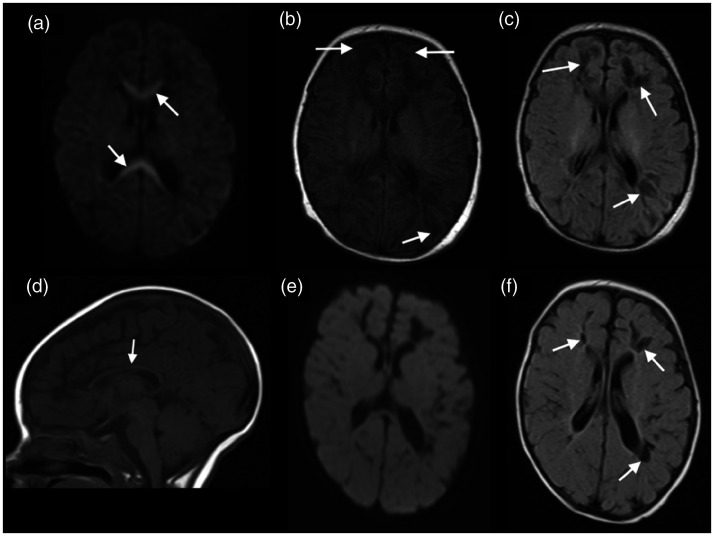

A 4-day-old neonate presented with a reduced level of consciousness and convulsions. Complete blood count showed severe thrombocytopenia. Brain MRI on the 17th day of life showed areas of restricted diffusion in the entire corpus callosum, associated with cavitations in the frontal and parietal lobes, as well as subcortical white matter lesions with hypointense signal in T1-weighted imaging and FLAIR and hyperintense signal in T2-weighted imaging. A follow-up brain MRI, in the 3rd month of life demonstrated that the diffusion in the corpus callosum had returned to normal, but the corpus callosum had thinned, the frontoparietal cavitations had shrunk, presenting a perivascular distribution, the subcortical lesions had resolved and the volume of the lateral ventricles had increased (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 17-day-old neonate with Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) showed restricted diffusion in the corpus callosum (arrows in (a)), associated with subcortical vasogenic oedema, on T1-weighted imaging (arrows in (b)), and cavitations in the frontal and parietal lobes, suggesting a perivascular distribution better seen on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (arrows in (c)). Follow-up brain MRI, in the 3rd month of life demonstrated thinning of the corpus callosum (arrow in (d)), without restricted diffusion (e) and that the cavitations had shrunk and the subcortical lesions had improved (arrows in (f)).

Case 2

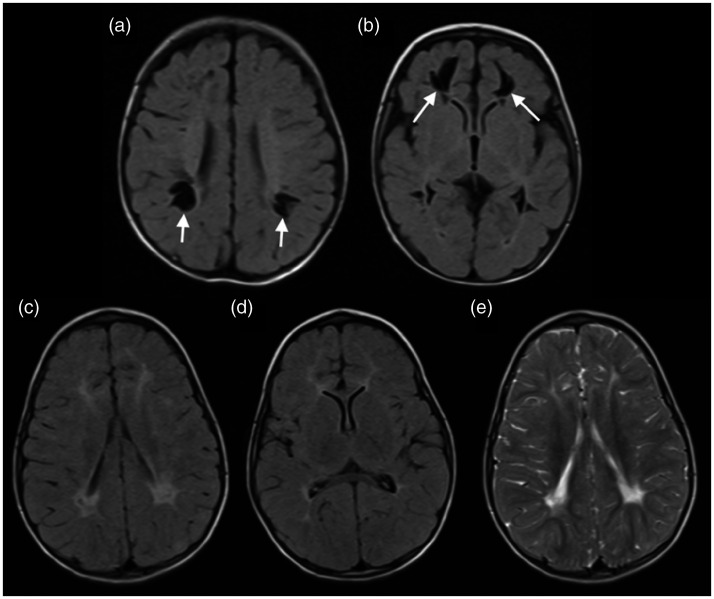

A 5-day-old neonate presented with fever and reduced level of consciousness. A brain MRI on the 30th day of life demonstrated white matter cavitations in the frontal and parietal lobes, also suggestive of perivascular distribution, without areas of restricted diffusion, associated with corpus callosum thinning. A follow-up brain MRI at 17 months of age showed that the cavitations had shrunk, presenting with perilesional areas with hyperintense signal on T2-weighted imaging and FLAIR, suggesting gliosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 30-day-old neonate with Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) demonstrated white matter cavitations in the frontal and parietal lobes, suggestive of perivascular distribution in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (arrows in (a) and (b)). Follow-up MRI, 1.5 years later, showed that the cavitations had shrunk, presenting with perilesional areas with hyperintense signal on FLAIR ((c) and (d)) and T2-weighted imaging (e).

Case 3

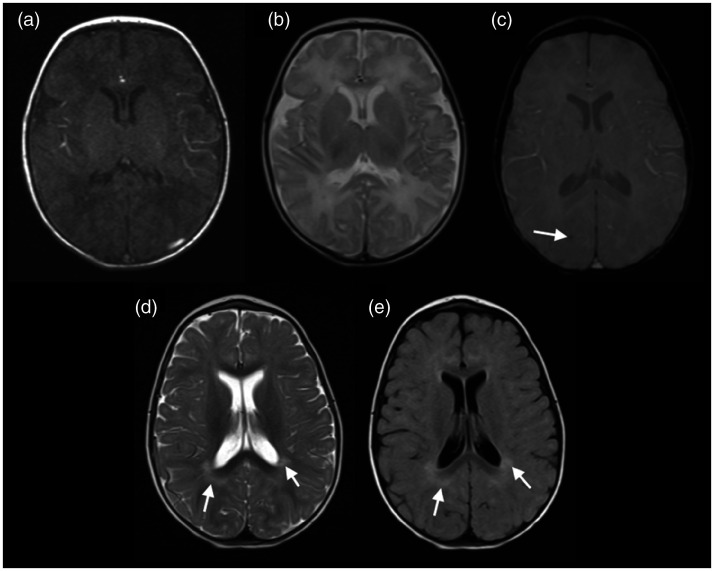

A 6-day-old neonate presented with fever and difficulty feeding. Brain MRI on the 25th day of life demonstrated only a discrete focus of haemorrhage in the right parietal lobe on T2*-weighted imaging, with normal myelination for age. A follow-up brain MRI at 11 months of age showed persistence of the focus of haemorrhage, and that cerebral myelination had evolved normally (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 25-day-old neonate with Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection demonstrated a normal myelination for age in T1 and T2-weighted imaging ((a) and (b)) and a discrete focus of haemorrhage in the right parietal lobe on T2*-weighted imaging (arrow in (c)). Follow-up brain MRI, at almost 1 year of age, showing only areas of terminal myelination (arrows in (d) and (e)). Despite having an unremarkable brain MRI, the patient’s neurocognitive development was delayed.

All neonates had normal prenatal exams and were born asymptomatic, without complications. All participants tested negative for syphilis, HIV, herpes, Zika, dengue, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B and rubella. Blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid samples of the neonates tested positive for CHIKV by RT–PCR. By the second brain MRI, all patients exhibited neurocognitive development delay.

The delivery room and neonatal units were well insulated, air-conditioned and mosquito-free. In addition, none of our participants showed any evidence of mosquito bites.

Gestational age at the onset of maternal symptoms, gestational age at birth, neonate age at symptom onset and MRI features are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

In this study, we reported the longitudinal evolution of brain lesions detected by MRI in three confirmed cases of mother-to-child CHIKV transmission. All participants were born asymptomatic and developed symptoms in the first days of life. Follow-up scans showed a reduction in the volume of cavitations, with or without a T2 hyperintensity in the surrounding brain parenchyma. In the patient who initially presented with corpus callosum-restricted diffusion, this finding had resolved at follow-up 2.5 months later.

Previous studies have documented neurocognitive sequelae in neonates who acquired CHIKV through vertical transmission. About half of such symptomatic neonates have neurocognitive development delay.4 Gérardin et al.6 demonstrated that perinatally infected children had moderate or severe global developmental delay more frequently than controls by their second birthday. Among vertically infected children, 73.9% had neurodevelopmental deficits, particularly in coordination and language.6 Laoprasopwattana et al.7 compared pregnancies in which the mother either tested negative for CHIKV or was positive early in gestation, and reported no adverse infant outcomes. The absence of adverse events in their cohort may be attributable to the fact that none of the pregnant women had CHIKV infection immediately before delivery. In the current study, all women were symptomatic during delivery, and the three neonates presented characteristic symptoms of CHIKV infection in the first week of life, along with neurocognitive development delay during subsequent follow-up. The overall risk of symptomatic neonatal CHIKV infection is estimated to be 50% in cases of intrapartum maternal infection, whereas mothers with antepartum infections do not transmit.4

Previous authors have demonstrated that brain MRIs of children with perinatally acquired CHIKV infection exhibit three patterns, depending on the disease stage and/or severity.5,8,9 In the early phase, one can see white matter-restricted diffusion, with a perivascular distribution and in the corpus callosum; in the subacute phase, MRI demonstrates vasogenic oedema, which can regress or evolve towards cavitation; and the chronic phase, characterised by cavitations,8 which can shrink in the long-term follow-up. The first case presented here demonstrated a mixture of lesions in the first scan: restricted diffusion in the corpus callosum, which regressed in the second examination; subcortical frontoparietal lesions, which resolved in the second scan and likely represented vasogenic oedema; and cavitations, which had shrunk by the second scan. The second patient underwent the first MRI in the chronic phase of the disease, presenting with cavitations, with a perivascular distribution, without areas of restricted diffusion, which had also shrunk 17 months later. The third patient, despite presenting with delayed neurocognitive development, had an almost normal brain MRI, with only a haemorrhagic focus, which would not explain the chronic complications of perinatal CHIKV infection, suggesting that the brain injury caused by the infection is more extensive than shown by MRI. Therefore, although previous studies have shown the presence of restricted diffusion and brain cavitations in the white matter, including the corpus callosum, in the current study we demonstrated that, in the long term, these cavitations reduce in volume and that the lesions seen in brain MRI may not reflect the actual neuronal damage caused by the infection.

Other diseases can also cause lesions similar to those observed in patients with vertically transmitted CHIKV infection, such as hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy, and neonatal infection by herpes simplex virus, parechovirus, enterovirus and rotavirus.10 Necrosis secondary to hypoxic-ischaemic injury results in loss of periventricular white matter, passive ventriculomegaly with irregular margins and thinning of the corpus callosum. Cavitations represent end-stage disease.11 A previous experimental study with mouse models of CHIKV infection found that viral load was high in the choroid plexus, ependymal wall, leptomeninges and Virchow–Robin space cells, whereas there was no viral load in the brain parenchyma, suggesting that the blood–brain barrier was intact, and that the pathophysiology of CHIKV brain infection may have a vascular origin.12 This could explain the similarity of imaging findings between mother-to-child CHIKV infection lesions and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy.

In addition, it should be noted that distinguishing CHIKV perinatal infection from enterovirus, rotavirus and neonatal herpes simplex encephalitis by imaging studies alone may be impossible.10 Therefore, perinatal infection with CHIKV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of neonatal sepsis, when the mother was symptomatic in the peripartum period. Despite this, the MRI aspect of brain lesions secondary to mother-to-child CHIKV transmission is different from other congenital infections, such as cytomegalovirus, Zika, rubella and toxoplasmosis, which can cause microcephaly, cerebral calcifications and malformations of cortical development, which are not seen in CHIKV infection.13–15 In addition, it is important to be aware that on long-term follow-up, patients with perinatal CHIKV infection may experience neurocognitive sequelae and an absence of MRI-detected brain lesions.

Although the brain MRI aspect of perinatal CHIKV infection is not pathognomonic, all participants were born without complications and their symptoms began only days after birth. In addition, except for CHIKV infection near the delivery day, all the mothers had normal prenatal exams. Also, none of the neonates showed evidence of mosquito bites, and all tested positive for CHIKV infection and negative for other infections. Therefore, we can attribute the brain lesions to mother-to-child CHIKV transmission.

A limitation of this study is its small sample size. Furthermore, the three patients presented at different stages of the disease, with distinct imaging findings in the first scan. However, all participants had a confirmed diagnosis of vertically transmitted CHIKV infection, and other co-infections and peripartum complications were excluded.

Conclusion

The chronic complications of perinatally acquired CHIKV infection observed in longitudinal imaging studies resemble those of periventricular leukomalacia and other vertically transmitted infections. In addition, brain MRI may not demonstrate the true extent of lesions secondary to the infection.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: No funding was received for this study.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

ORCID iDs: Diogo Goulart Corrêa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4902-0021

References

- 1.Morrison CR, Plante KS, Heise MT. Chikungunya virus: current perspectives on a reemerging virus. Microbiol Spectr 2016; 4: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villamil-Gómez W, Alba-Silvera L, Menco-Ramos A, et al. Congenital Chikungunya virus infection in Sincelejo, Colombia: a case series. J Trop Pediatr 2015; 61: 386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritel X, Rollot O, Gerardin P, et al. Chikungunya virus infection during pregnancy, Reunion, France, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16: 418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contopoulos-Ioannidis D, Newman-Lindsay S, Chow C, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of Chikungunya virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12: e0006510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrêa DG, Freddi TAL, Werner H, et al. Brain MR imaging of patients with perinatal Chikungunya virus infection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020; 41: 174–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gérardin P, Sampériz S, Ramful D, et al. Neurocognitive outcome of children exposed to perinatal mother-to-child Chikungunya virus infection: the CHIMERE cohort study on Reunion Island. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8: e2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laoprasopwattana K, Suntharasaj T, Petmanee P, et al. Chikungunya and dengue virus infections during pregnancy: seroprevalence, seroincidence and maternalefetal transmission, southern Thailand, 2009–2010. Epidemiol Infect 2016; 144: 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gérardin P, Barau G, Michault A, et al. Multidisciplinary prospective study of mother-to-child Chikungunya virus infections on the island of La Réunion. PLoS Med 2008; 5: e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramful D, Carbonnier M, Pasquet M, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of Chikungunya virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007; 26: 811–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarma A, Hanzlik E, Krishnasarma R, et al. Human parechovirus meningoencephalitis: neuroimaging in the era of polymerase chain reaction-based testing. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019; 40: 1418–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bano S, Chaudhary V, Garga UC. Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a radiological review. J Pediatr Neurosci 2017; 12: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couderc T, Chrétien F, Schilte C, et al. A mouse model for Chikungunya: young age and inefficient type-I interferon signaling are risk factors for severe disease. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4: e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radaelli G, Lahorgue Nunes M, Bernardi Soder R, et al. Review of neuroimaging findings in congenital Zika virus syndrome and its relation to the time of infection. Neuroradiol J 2020; 33: 152–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreula CF, Marano G, Kambas I. Viral encephalitis. Rivista Neuroradiol 1997; 10: 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez TR, Datlow MD, Nidecker AE. Diffuse periventricular calcification and brain atrophy: a case of neonatal central nervous system cytomegalovirus infection. Neuroradiol J 2016; 29: 314–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]