Abstract

Background:

Tuberculosis preventive treatment (TPT) is a critical intervention to reduce tuberculosis mortality among people living with HIV (PLHIV). To facilitate scale-up of TPT among PLHIV, the Nigeria Ministry of Health and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Nigeria, supported by US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief implementing partners, launched a TPT-focused technical assistance strategy in high-volume antiretroviral treatment (ART) sites during 2018.

Setting:

Nigeria has an estimated 1.9 million PLHIV, representing the second largest national burden of PLHIV in the world, and an estimated 53% of PLHIV are on ART.

Methods:

In 50 high-volume ART sites, we assessed readiness for TPT scale-up through use of a standardized tool across the following 5 areas: clinical training, community education, patient management, commodities and logistics management, and recording and reporting. We deployed a site-level continuous quality improvement strategy to facilitate TPT scale-up. Implementing partners rapidly disseminated best practices from these sites to across all CDC-supported sites and reported aggregate data on monthly TPT initiations.

Results:

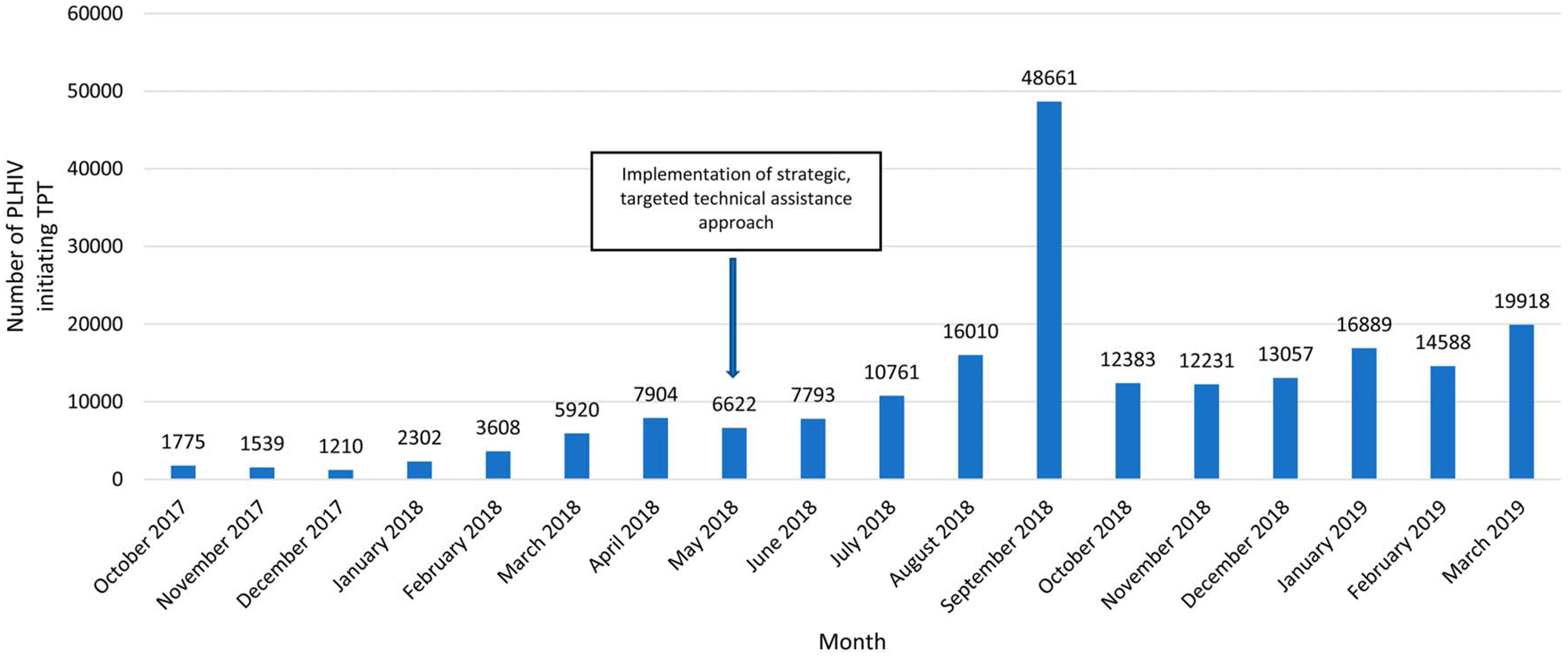

Through this targeted assistance and rapid dissemination of best practices to all other sites, the number of PLHIV who initiated TPT across all CDC-supported sites increased from 6622 in May 2018, when the approach was implemented, to 48,661 in September 2018. Gains in monthly TPT initiations were sustained through March 2019.

Conclusions:

Use of a standardized tool for assessing readiness for TPT scale-up provided a “checklist” of potential barriers to TPT scale-up to address at each site. The quality improvement approach allowed each site to design a specific plan to achieve desired TPT scale-up, and best practices were implemented concurrently at other, smaller sites. The approach could assist scale-up of TPT among PLHIV in other countries.

Keywords: tuberculosis, HIV, quality improvement, Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

Nigeria, with an estimated 1.9 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) in 2018, represents the second largest national burden of PLHIV in the world.1 Among all PLHIV, an estimated 53% were on antiretroviral treatment (ART) in 2018,1 and of those on ART, 807,094 were supported by funding from the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).2 Of those supported by PEPFAR, 491,995 (61%) were supported through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated there were 429,000 incident cases of tuberculosis (TB) disease, including 53,000 among PLHIV, and 32,000 estimated TB deaths among PLHIV in Nigeria.3 Addressing TB disease incidence and mortality among PLHIV in Nigeria requires improvements in TB disease detection, diagnosis, and treatment, but focusing only on these activities does not address treatment of TB infection. Reducing morbidity and mortality of TB disease among PLHIV in Nigeria depends, in part, on ensuring access to TB preventive treatment (TPT) among this population.

TPT is a critical intervention in reducing the development of TB disease among PLHIV. Although ART reduces the incidence of TB disease among PLHIV, incidence is reduced further, independent of ART, when a one-time, standardized course of TPT is also given.4–7 Following WHO recommendations, Nigeria adopted TPT as the standard of care for PLHIV in its HIV guidelines in 2015, yet implementation and scale-up of TPT in HIV treatment clinics in Nigeria has been slow; only an estimated 39% of PLHIV newly enrolled in HIV care received TPT in 2017.8

Initial barriers to scale-up included administrative and logistic barriers. In Nigeria, HIV program implementation policy is made by the National AIDS/Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) Control Program within the Federal Ministry of Health, whereas procurement of medication for ART sites is performed by a national integrated HIV commodities partner funded through PEPFAR. TB policy and procurement of TB medication, including isoniazid (INH), the medication most widely used in Nigeria for TPT, are performed by the National TB and Leprosy Control Program, with funding through the Global Fund. HIV care and ART are delivered in dedicated ART sites in public and private facilities by staff supported by local and international nongovernment implementing partners (IPs) of US government agencies, including CDC, the US Agency for International Development, and the Department of Defense, with funding from PEPFAR. TB care and treatment are delivered in dedicated TB treatment sites, which may or may not be colocated with ART sites. Although this structure, in which different agencies were in charge of different parts of TPT policy and delivery, posed administrative and logistic barriers to TPT drug delivery to PLHIV in ART sites, these barriers were addressed through integration of INH procurement and delivery into the national ART Logistics Management and Information System.9 Once those barriers were removed, there remained the challenge of getting TPT into widespread clinical use in HIV care.

In the PEPFAR model of HIV programming, to implement or expand an intervention in HIV care, the US CDC country offices provide guidance and focused technical assistance to IPs, who then implement initiatives and disseminate best practices to all supported sites. Programmatic implementation of the intervention is then measured in aggregate across all CDC-supported sites.

Following this model, to facilitate programmatic scale-up of TPT in clinical practice among PLHIV nationally, the CDC Nigeria, supported by PEPFAR, its 4 treatment delivery IPs, and Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health staff launched a targeted technical assistance strategy during May to September 2018 focused on understanding and removing barriers to TPT uptake in CDC-supported high-volume ART sites, with the intention that best practices from these sites would be adopted in other, smaller sites. Their experience in this endeavor provides lessons that could assist scale-up of TPT among PLHIV in other countries.

APPROACH

The approach to scaling up TPT for PLHIV in CDC-supported sites in Nigeria undertaken during 2018 consisted of the deployment of strategic, targeted technical assistance to increase TPT initiations in the 50 highest volume ART sites supported by the CDC. These 50 sites represented 4% of all CDC-supported sites nationally but were the treatment sites for 46% of all CDC-supported PLHIV on ART. In each of these 50 sites, CDC staff and the IP supporting the site assessed readiness for TPT scale-up through the application of a standardized “TPT clinical site readiness tool.” This tool included a checklist of necessary standardized training materials, job aids, and monitoring and evaluation forms; a questionnaire for clinicians and program managers about TPT policies; and an abbreviated review of deidentified TPT registers. This tool focused on program components across 5 key intervention areas as follows: clinical training, community education, patient management, commodities and logistics management, and monitoring and evaluation activities, including recording and reporting.10 The use of this tool identified site-level barriers to evaluation for TPT eligibility, TPT offer, and TPT initiation among PLHIV receiving care at these sites. IPs, with ongoing support from CDC staff, then deployed a site-level continuous quality improvement strategy to facilitate TPT scale-up, which included shared discussion and generation of root causes of identified barriers, development and implementation of change ideas to address root causes, and iterative review of data to demonstrate effectiveness of interventions to scale-up TPT. This strategy allowed CDC staff and IPs to document best practices for TPT scale-up and rapidly disseminate them to other ART sites, even concurrent to scale-up in the 50 largest sites; in this programmatic initiative, improvements in TPT implementation were intended across all CDC-supported sites. Data reviewed included indicators of numbers of PLHIV with clinic visits, number eligible for TPT initiation, and number initiating TPT. These data were collected by IP staff using 2 nationally standardized forms: a patient-level form within an individual’s medical file and a site-level TPT register. Data on TPT initiations were reported in aggregate across all CDC-supported sites to CDC on a monthly basis.

Because this activity consisted of monitoring and improvement of a public health program with deidentified data and no perceived ethical risk to patients, no informed consent was obtained. This public health program activity review was covered under a nonresearch determination from the CDC Center for Global Health.

Barriers to TPT scale-up were site specific, and therefore, the interventions varied (Table 1). Interventions to address gaps in clinical training, community education, and patient management included sensitization of clinicians through direct mentorship and education sessions on the benefits of TPT, the components of effective TPT pretreatment counseling, and the importance of management of adherence and of any TPT-related adverse event.

TABLE 1.

Example Barriers and Interventions in TPT Scale-Up Among PLHIV in CDC-Supported Sites—Nigeria, 2018–2019

| Section(s) of Tool | Example Barrier Identified | Example Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical training, community education, and patient management | Clinician concerns about effectiveness of TPT, potential resistance to FNH, and TPT-related adverse events | Sensitization of clinicians through direct mentorship and education sessions on benefits of TPT, effective TPT pretreatment counseling, management of adherence, and TPT-related adverse events |

| Community education | Lack of TPT demand from patients | Demand creation through convening patient education seminars in the waiting room on clinic days |

| Patient management | Lack of clinician prescribing of TPT | Periodic audit of all medical files of PLHIV seeking care to note eligibility for TPT |

| Periodic reviews of patient-level TPT form and site-level TPT register | ||

| Dissemination of TPT algorithms and job aids Use of a checklist to identify TPT eligibility, adverse events, and outcome | ||

| Commodities and logistics management | Forecasting and ordering of INH for TPT based on historic use rather than planned scale-up | Kitting of INH for each PLHIV initiating TPT to ensure supply |

| Linking TPT pickup with ART pickup to forecast numbers of TPT courses needed | ||

| Recording and reporting TPT initiations | Inconsistent recording or use of nonstandard indicators |

Dissemination and training on correctly filling nationally standardized TPT monitoring and evaluation tools |

Interventions to improve demand creation, a component of the community education section of the tool, included convening patient education seminars in the waiting room on clinic days. Interventions at sites to improve clinician prescribing, a component of the patient management section of the tool, included a periodic audit of all medical files of PLHIV receiving care at the site to note eligibility for TPT and attaching a colored label to the files as a clinician “alert.” It also included ensuring that each PLHIV seeking care was assessed for prescription of TPT at each visit using periodic reviews by IP staff of the patient-level TPT form in the medical file and the site-level TPT register, disseminating TPT administration algorithms and job aids, and using a checklist to identify patients’ TPT eligibility or contraindications, any adverse events, and outcomes.

Interventions to address gaps in commodities and logistics management included training for ART site pharmacists and logisticians on appropriate forecasting of quantification and requisition of INH. Forecasting was based on the principles of ensuring availability of a full six-month course for PLHIV initiating TPT using a kitting system (ie, counting and name tagging all medication for a single complete six-month course at initiation) and of linking patient TPT pickup with ART pickup.

Finally, interventions to address gaps in recording and reporting included dissemination of and training on correctly filling nationally standardized TPT monitoring and evaluation tools, consisting of a patient-level form within an individual’s medical file and a site-level TPT register. Both of these tools included documentation of screening for TB disease, contraindications for TPT, subsequent assessment of eligibility for TPT, and documentation for assessing critical monitoring components while the patient is on TPT: development of presumptive TB disease, adverse events, and outcome.

To document overall progress of the scale-up effort, monthly aggregate site-level TPT register data, all sites supported by each IP, were aggregated to give total TPT initiations by month across all CDC-supported sites.

RESULTS

After implementing this targeted assistance and quality improvement approach to scale-up TPT among PLHIV in Nigeria during 2018 and as best practices for TPT scale-up in clinical care were disseminated to all other CDC-supported sites by IPs, the number of PLHIV who initiated a course of INH for TPT across all CDC-supported ART sites increased from 1775 in October 2017 to 6622 in May 2018, the month of introduction of this approach, to 48,661 in September 2018, the end of the PEPFAR fiscal year (Fig. 1). The cumulative number of PLHIV initiating TPT during PEPFAR fiscal year 2018, from October 2017 to September 2018, was 114,105, with 89,847 (79%) initiating during the period of the described intervention. The highest number of TPT initiations was in September 2018, the last month of the PEPFAR fiscal year. The number of TPT initiations was sustained across the subsequent 6 months, with 89,066 PLHIV initiating TPT across all CDC-supported sites during October 2018 to March 2019. The calculated median monthly number of TPT initiations during October 2018 to March 2019 was 13,823, higher than the calculated median monthly number of TPT initiations of 9333 during April 2018 to September 2018. During the period October 2017 to March 2019, the total PLHIV initiating TPT were 203,171. The 203,171 PLHIV initiating TPT during October 2017 to March 2019 represented a TPT coverage of 45% of the 454,663 total PLHIV on ART supported by the CDC through PEPFAR in March 2019.2

FIGURE 1.

Number of PLHIV initiating TPT across all ART sites supported by CDC, by month—Nigeria, October 2017–March 2019.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of this targeted approach with concurrent dissemination of best practices to other, smaller CDC-supported sites facilitated the rapid scale-up of TPT among PLHIV receiving care across all CDC-supported sites in Nigeria. The number of monthly TPT initiations increased steadily during May to September 2018; then was sustained at a consistent level during October 2018 to March 2019, at a median monthly value higher than that of the preceding 6 months, indicating improvements in TPT implementation in care initially, followed by routine implementation in care thereafter. The outlier in number of monthly initiations was in September 2018; of note, this coincides with the end of the PEPFAR fiscal year, when IPs do a final audit of interventions and ensure full implementation of quality improvement initiatives, including repeat data reviews, in preparation for annual reporting. Thus, this high number of TPT initiations in 1 month may be attributed to increased supervision of clinical care to ensure all eligible PLHIV were offered TPT that month or recording and reporting of backlogged TPT initiations from previous months that had not previously been reported.

Use of a standardized tool for assessing readiness for TPT scale-up provided a “checklist” of potential barriers to TPT scale-up that could then be catalogued, prioritized, and addressed at each site. Training on standardized TPT monitoring and evaluation tools allowed improved data completeness and validity on important national TPT outcome indicators of initiations and completions.

Importantly, the focus on the 50 highest-volume ART sites allowed CDC staff providing technical assistance to give extensive support during initial contact with those sites, and the fact that IPs then concurrently brought best practices from those sites to other, smaller sites provided a “force multiplier” effect of that technical assistance. An important limitation in this initiative is that because we examined data in aggregate across all CDC-supported sites, rather than only in the 50 sites receiving focused technical assistance, we cannot say if gains in these 50 sites themselves drove the increase in TPT initiation seen collectively across all CDC-supported sites.

The programmatic quality improvement approach used here allowed site staff to participate in generation of change ideas, and it allowed each site to design a specific improvement plan that could change over the course of time. This approach of combining focused initial attention on high-volume sites with an agency-wide quality improvement approach has now been used for other HIV/TB services in CDC-supported sites in Nigeria and by other PEPFAR agencies in Nigeria.11 It could be used in other low-resource settings to facilitate implementation and scale-up of TPT.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. Country Factsheets: Nigeria. 2020. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/nigeria. Accessed July 12, 2020.

- 2.PEPFAR. PEPFAR Panorama: OU Results Nigeria. 2018. Available at: https://pepfar-panorama.org/PEPFARlanding. Accessed July 21, 2020.

- 3.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019: Country Profiles. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/tb19_Report_country_profiles_15October2019.pdf?ua=1. Accessed July 12, 2020.

- 4.Ayele HT, Mourik MS, Debray TP, et al. Isoniazid prophylactic therapy for the prevention of tuberculosis in HIV infected adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badje A, Moh R, Gabillard D, et al. Effect of isoniazid preventive therapy on risk of death in West African, HIV-infected adults with high CD4 cell counts: long-term follow-up of the Temprano ANRS 12136 trial. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5:e1080–e1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group; Danel C, Moh R, et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:808–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pathmanathan I, Ahmedov S, Pevzner E, et al. TB preventive therapy for people living with HIV: key considerations for scale-up in resource-limited settings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22:596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Profile: Nigeria. 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 9.Odume B, Meribe SC, Odusote T, et al. Taking tuberculosis preventive therapy implementation to national scale: the Nigerian PEPFAR program experience. Public Health Action. 2020;10:7–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PEPFAR. PEPFAR Solutions: TB Preventive Treatment (TPT) Implementation Tools. 2020. Available at: https://www.pepfarsolutions.org/tools-2/2018/9/25/tpt-implementation-tools. Accessed July 12, 2020.

- 11.Meribe SC, Adamu Y, Adebayo-Abikoye E, et al. Sustaining tuberculosis preventive therapy scale-up through direct supportive supervision. Public Health Action. 2020;10:60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]