Abstract

BACKGROUND

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) has gained popularity as a minimally invasive approach and is currently widely used to treat pancreatic cancer-associated pain. However, response to treatment is variable.

AIM

To identify the efficacy of EUS-CPN and explore determinants of pain response in EUS-CPN for pancreatic cancer-associated pain.

METHODS

A retrospective study of 58 patients with abdominal pain due to inoperable pancreatic cancer who underwent EUS-CPN were included. The efficacy for palliation of pain was evaluated based on the visual analog scale pain score at 1 wk and 4 wk after EUS-CPN. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to explore predictors of pain response.

RESULTS

A good pain response was obtained in 74.1% and 67.2% of patients at 1 wk and 4 wk, respectively. Tumors located in the body/tail of the pancreas and patients receiving bilateral treatment were weakly associated with a good outcome. Multivariate analysis revealed patients with invisible ganglia and metastatic disease were significant factors for a negative response to EUS-CPN at 1 wk and 4 wk, respectively, particularly for invasion of the celiac plexus (odds ratio (OR) = 13.20, P = 0.003 for 1 wk and OR = 15.11, P = 0.001 for 4 wk). No severe adverse events were reported.

CONCLUSION

EUS-CPN is a safe and effective form of treatment for intractable pancreatic cancer-associated pain. Invisible ganglia, distant metastasis, and invasion of the celiac plexus were predictors of less effective response in EUS-CPN for pancreatic cancer-related pain. For these patients, efficacy warrants attention.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound, Celiac plexus neurolysis, Pancreatic cancer, Pain, Predictor

Core Tip: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) is widely used to treat pancreatic cancer-associated pain. However, response to treatment is variable. The procedure is not always effective, is often variable, and yields transient results. The data on determinants of pain relief response following EUS-CPN are limited and still need to undergo further exploration. Our study found that invisible ganglia, presence of distant metastases, and celiac plexus invasion were considered to be significantly negative variables. The strongest predictor of response was celiac plexus invasion. Moreover, tumors located at the body/tail predicted a better response than those with tumors at the pancreatic head/neck.

INTRODUCTION

Up to 90% advanced pancreatic cancer patients experience difficult-to-control pain syndromes[1]. Conventionally, pain is alleviated using a three-step analgesic ladder approach beginning with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents followed by escalating doses of opiates[2]. However, pain is always refractory in some cases, posing a challenge to the physician. A high dose of such drugs still cannot provide adequate analgesia, especially for those patients experiencing intolerable drug-related side effects that can markedly reduce survival. In these patients, interventional pain techniques may be indicated.

In endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN), a neurolytic agent disrupts the pain signal transductions from the afferent nerves to the spinal cord, and it has been widely applied as a minimally invasive approach. This procedure is able to decrease significantly the daily usage of morphine medications and relieve pain. The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommends EUS-CPN for treatment of severe cancer-associated pain[3]. Varied studies have reported that over 80% of patients achieved sustainable pain relief after treatment, and many even to the time of death[4,5].

However, the procedure is not always effective, is often variable, and has transient results. Subsequent studies showed the proportion of patients benefiting from pain amelioration is quite variable at 50% to 80%[6-8]. Optimization of treatment outcomes for the technique of neurolysis involves direct injection into the celiac ganglia, broad injection to involve the area around the superior mesenteric artery, and bilateral vs unilateral injection; lesion characteristics for optimization have been reported as well, but findings are controversial[7,9-12]. EUS-CPN is not recommended for patients suspected of having unfavorable outcomes. Moreover, the data on determinants of pain relief response following EUS-CPN are limited and still need to undergo further exploration. In this study, we attempt to summarize the predictive factors for response to EUS-CPN in pancreatic cancer with the goal of providing rational selection of the therapeutic strategies to alleviate pancreatic cancer-associated pain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

A total of 58 patients who were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and underwent EUS-CPN over a 4-year period (from January 2015 to December 2018) were included in this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients over the age of 18 years; (2) Complete information; (3) Presence of unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer; (4) No receiving any palliative chemotherapy or radiation therapy; (5) No bleeding tendency (international normalized ratio ≤ 1.5 or platelet count ≥ 50,000 × 109/L); (6) No esophageal or gastric varices; and (7) Enduring abdominal or back pain due to confirmed pancreatic malignancy diagnosed by EUS guided fine-needle aspiration/ biopsy or percutaneous biopsy. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (IORG No: IORG0003571). All patients signed informed consent for EUS operation, and data were anonymized and de-identified.

Endoscopic procedure in EUS-CPN

Patients were hydrated with 500-1000 mL saline solution during the procedure to minimize the risk of hypotension. They were placed in the left lateral decubitus position, and propofol was administered for deep sedation. Vital signs were continuously monitored with an automated non-invasive blood pressure mea-surement, electrocardiogram, and pulse oximetry.

EUS-CPN was performed by using the Olympus processor EU-ME2 with a linear array endoscopic ultrasonography (GF-UCT 260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). By tracing the aorta under real-time EUS guidance, the base of the celiac artery was identified. Celiac ganglia could be visualized between the celiac artery and the left adrenal gland. Typically for CPN unilateral injection, an Echo Tip 22-gauge needle (Cook Medical, Inc., Winston-Salem, NC, United States) primed with normal saline solution was inserted into the operating channel, affixed to the hub, and placed adjacent to the base of the celiac trunk at its origin from the aorta. In cases with bilateral injection, the same procedure was done, but injections were done at both sides of the celiac trunk with clockwise and counter-clockwise rotation (half of the dehydrated 98% absolute alcohol was injected in each side)[13,14]. After confirming no backflow of blood occurred, the celiac plexus injection by dehydrated 98% absolute alcohol was directly applied. A dense hyperechoic cloud was usually seen in the area of injection, and the injection was continued until spilling to the periganglionic space (Supplemental material). Whether a bilateral injection was carried out depended on the locations of intervening vessels, the tumor status, and invasion of the celiac plexus or not. Tumors extending to the para-aortic region from the level of the celiac axis to the origin of SMA were considered invasive of the celiac plexus. No antibiotics were administered before or post-CPN. All procedures were performed by a single endosonographer.

Pain scores

Pain intensity was evaluated by telephone interview and done objectively using a continuous visual analog scale (VAS), with 0 as no pain and 10 as worst possible pain. Detailed instructions explaining how to assess the VAS were read and the patients then informed the best VAS score that reflected their pain status. Good pain relief was defined as a decrease in the pain score by ≥ 3 or a ≥ 30% reduction in baseline pain without any increase in the narcotic daily dosing[15]. If the patients had no pain improvement or markedly increased pain or required additional doses of narcotic agents 1 wk after the procedure, the procedure was considered to be a failure.

Outcomes measures

Primary outcomes included the efficacy of EUS-CPN and the difference in pain control by VAS was compared. Pain management was evaluated at 1 wk and 4 wk after the CPN procedure. Secondary outcomes included analgesia requirement and adverse events. To minimize subjective variations in the evaluation of outcomes, the same authorized staff who was unaware of the detailed endoscopic procedures collected the outcomes of all patients.

Data collection

To analyze all possible factors that could affect the determinants of pain response in patients undergoing EUS-CPN for abdominal pain caused by pancreatic cancer, the following data were collected for each patient: Information regarding tumor characteristics (i.e. size, location, vascular invasion, and distant metastasis), procedure details (including procedure method, dehydrated alcohol dose, visible or invisible ganglia, and intra-procedural heart rate change), the incidence of adverse events, and the dose of morphine medications administered before and after the assignment intervention. Heart rate change was defined as a decrease of ≥ 5 beats for ≥ 10 s during alcohol injection. Other covariates, including demographics (i.e. age, gender, initial VAS score), symptom (i.e. abdominal pain concomitant with jaundice and presence of ascites), were also collected.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as counts and percentages. Continuous variable results were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Associations among various categorical variables were constructed by Pearson’s chi-squared test, and non-categorical variables were analyzed by t tests. Subsequently, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were carried out to examine potential predictors of pain response to the CPN procedure. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software20.0 (SPSS, Armonk, NY, United States). Values were considered to be statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.05 (two-sided).

RESULTS

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

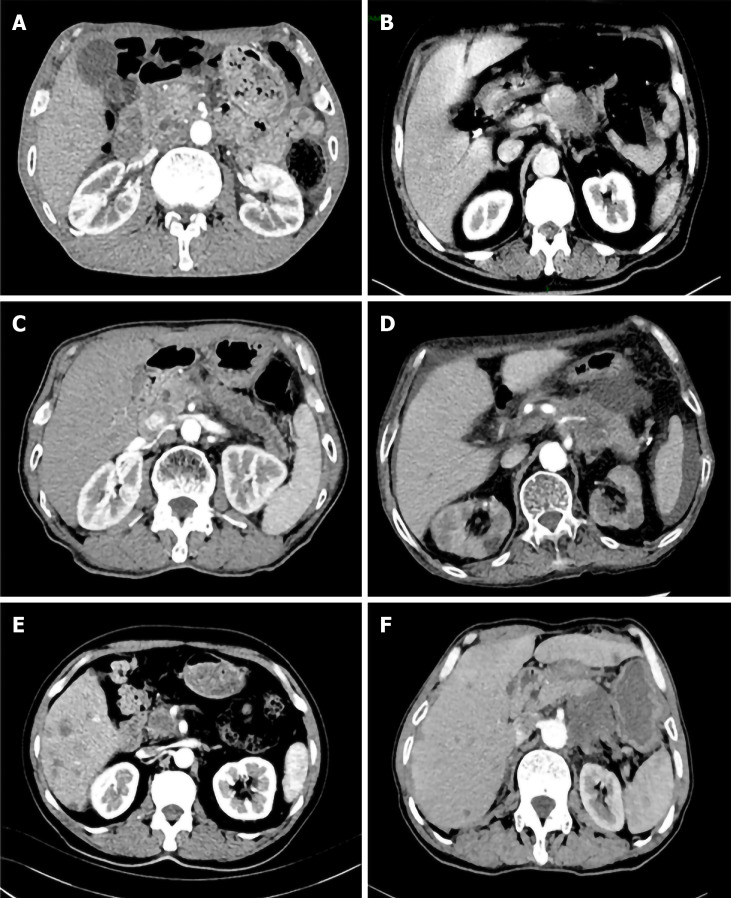

A total of 58 patients with abdominal pain due to inoperable pancreatic cancer who underwent EUS-CPN were included. These cases consisted of 33 men and 25 women with a mean age of 67 years (range: 54-73 years). Predominant distribution of tumor location in pancreas was located in the body/tail (69.0%), and mean tumor diameter was 44.3 mm (range: 24-100 mm). Fifty-one patients were referred for initial evaluation of suspected pancreatic cancer and were first confirmed via EUS-fine needle aspiration (FNA) before undergoing EUS-CPN in the same session. The seven remaining patients had been previously diagnosed with pancreatic malignancy and were referred to our center for palliation with EUS-CPN only. The 51 patients had malignant tumors histologically confirmed by EUS-FNA of pancreas (n = 36), enlarged lymph nodes (n = 8), and liver metastases (n = 3) or ascites cytology (n = 4). Of the entire group of patients, visible pre-procedural celiac ganglia were present in 42 patients (72.4%) during the EUS session. Direct invasion of the celiac plexus was detected in 16 (27.6%) patients, whereas 26 (44.8%) patients had distant metastasis. The patient clinical demographics, disease, and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who underwent endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis [n (%), n = 58]

|

Independent variables

|

Total number

|

| Age in yr, range (mean) | 54–73 (67) |

| Gender, female/male | 25/33 |

| Symptom | |

| Abdominal pain concomitant with jaundice Tumor largest dimension in mm, range (mean) | 6 (10.3) |

| Ascites, slight or mild | 24–100 (44.3) |

| Tumor location | 4 (6.9) |

| Pancreatic head/neck | |

| Pancreatic body/tail | 18 (31.0) |

| Initial VAS score, range (mean) | 40 (69.0) |

| Tramadol use before EUS-CPN | 6-10 (8) |

| Dose in mg, range (mean) | 51 (87.9) |

| Ganglia visualized | 0-240 (40) |

| Invasion of celiac plexus | 42 (72.4) |

| Distant metastasis | 16 (27.6) |

| Injected alcohol dose in mL, range (mean) | 26 (44.8) |

| Procedure method | 5–20 (10) |

| Unilateral | |

| Bilateral | 33 (56.9) |

| Intra-procedural decrease in heart rate | 25 (43.1) |

| decrease of ≥ 5 beats for ≥ 10 s | |

| 48 (82.8) |

EUS-CPN: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis; VAS: Visual analog scale.

Figure 1.

Varied pancreatic lesions are shown by contrast-enhanced computed tomography image. A: The lesion was located in head/neck of pancreas; B: The lesion was located in body/tail of pancreas; C: Pancreatic head lesion was associated with celiac trunk and celiac plexus invasion; D: The image showed a pancreatic body/tail invading the celiac plexus; E: Pancreatic head/neck lesion was accompanied with hepatic metastasis; F: Pancreatic body/tail lesion was accompanied with hepatic metastasis.

Efficacy for palliation of pain after EUS-CPN

With regard to therapeutic effect, the mean dose of alcohol injection was 10 mL (range: 5-20 mL). The mean initial VAS score was 8, and 51 patients (87.9%) were already taking narcotic analgesics prior to EUS-CPN. The tramadol dose used was 50 mg per time (range: 0–300). The rates of good pain response, defined as a drop of VAS score by ≥ 3 points in pain scale with subjective pain improvements without additional narcotics, were 74.1% and 67.2% of patients at 1 wk and 4 wk after EUS-guided neurolysis, respectively. The other patients were regarded as treatment failures, because either the pain was not better by ≥ 3 points from the baseline VAS score or they were feeling not better and increased their dose of tramadol medication after EUS-CPN. In the successful-treatment group, there was clearly a persistent treatment effect where pain relief lasted for 1–16 wk (until death in eight patients). Overall, there was a significant reduction in pain score from a mean of 8.2 at baseline to 4.4 at 1 wk (P = 0.004) and to 4.9 at 4 wk (P = 0.012) in all patients.

Predictors associated with pain response after EUS-CPN

To assess the predictive factors for pain response at 1 wk and 4 wk in patients who underwent EUS-CPN, variable data between the successful-treatment and the insufficient groups were compared. At 1 wk, tumors located in the body/tail of the pancreas and patients receiving bilateral procedure were weakly associated with a good response, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.094; P = 0.087, respectively) (Table 2). However, invisible ganglia and presence of distant metastasis were significant negative predictive factors in the univariable analysis [odds ratio (OR) = 3.574, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.80-14.24, P = 0.003; OR = 5.940, 95%CI: 1.31-11.82, P = 0.015]. Moreover, invasion of the celiac plexus was significantly associated with a poor pain response (OR = 7.922, P = 0.001). When these factors were subjected to multivariable logistic regression analysis, invisible ganglia, presence of distant metastases, and celiac plexus invasion were identified as significant negative independent pain response factors to EUS-CPN (Table 3). The other factors age, gender, symptom, tumor size, presence of ascites, and initial pain scores did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 2). Furthermore, neither the pre-intervention tramadol dose use nor injected alcohol dose correlated with the outcome of EUS-CPN. Finally, there was no statistical difference in response to diagnosis between patients who were presenting for initial evaluation by EUS-FNA and those who already had a biopsy-proven pancreatic cancer.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis of variables associated with pain response after 1 wk in the enrolled cohort of 58 patients

|

Independent variables

|

OR

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| Age in yr | 1.084 | 0.60-3.88 | 0.212 |

| Gender, female/male | 1.39 | 0.43-3.79 | 0.64 |

| Symptom | |||

| Abdominal pain concomitant with jaundice | 1.29 | 0.53–3.26 | 0.581 |

| Tumor largest dimension | 1.32 | 0.45-4.69 | 0.665 |

| Ascites | 1.772 | 0.59–6.84 | 0.437 |

| Tumor location | |||

| Pancreatic head/neck | 2.071 | 0.60-7.09 | 0.232 |

| Pancreatic body/tail | 0.617 | 0.65-10.40 | 0.094 |

| Initial VAS score | 2.231 | 0.76-5.41 | 0.132 |

| Tramadol use before EUS-CPN | 1.339 | 0.54-15.39 | 0.327 |

| Invisible ganglia | 3.574 | 1.80-14.24 | 0.003 |

| Invasion of celiac plexus | 7.922 | 2.24-25.93 | 0.001 |

| Distant metastasis | 5.94 | 1.31–11.82 | 0.015 |

| Injected alcohol dose | 3.825 | 1.12–13.42 | 0.437 |

| Procedure method | |||

| Unilateral | 1.677 | 0.84–11.48 | 0.591 |

| Bilateral | 0.489 | 0.11–1.12 | 0.087 |

| Intra-procedural decrease in heart rate | 1.011 | 0.91–2.08 | 0.933 |

OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; EUS-CPN: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis; VAS: Visual analogue scale.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis for predictors affecting pain response after 1 wk by endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis

|

Independent variables

|

OR

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| Ganglia invisible | 4.9 | 2.25-17.91 | 0.011 |

| Invasion of celiac plexus | 13.2 | 3.02-46.27 | 0.003 |

| Distant metastasis | 6.84 | 2.34–19.15 | 0.022 |

Summarizes the results of the multivariate analyses of the predictive factors associated with pain relief by EUS-CPN. The only independent predictive factors that achieved statistical significance in the univariate analysis were included. CI: Confidence interval; EUS-CPN: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis; OR: Odds ratio.

Similarly, at 4 wk, invisible ganglia, presence of distant metastases, and celiac plexus invasion were significant negative predictive factors in univariable analysis (P = 0.003, P = 0.009 and P = 0.001, respectively) (Table 4). At multivariate regression analysis of potential predictors, invisible ganglia, presence of distant metastases, and celiac plexus invasion were associated with a bad pain response (P = 0.037, P = 0.019 and P = 0.001, respectively). The strongest predictor of response was celiac plexus invasion, which yielded a 15-fold higher chance of response for those patients compared with those without celiac plexus invasion (Table 5).

Table 4.

Univariable analysis of variables associated with pain response after 4 wk in the enrolled cohort of 58 patients

| Independent variables | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age in yr | 1.091 | 0.63-3.94 | 0.209 |

| Gender, female/male | 1.124 | 0.47-3.99 | 0.532 |

| Symptom | |||

| Abdominal pain concomitant with | 1.384 | 0.43–4.82 | 0.618 |

| jaundice | 1.496 | 0.32-5.92 | 0.701 |

| Tumor largest dimension | 1.921 | 0.79–9.34 | 0.408 |

| Ascites | |||

| Tumor location | 3.59 | 0.40-10.06 | 0.184 |

| Pancreatic head/neck | 0.42 | 0.15-12.77 | 0.082 |

| Pancreatic body/tail | 2.93 | 0.42-8.17 | 0.101 |

| Initial VAS score | 2.91 | 0.24-19.40 | 0.149 |

| Tramadol use before EUS-CPN | 4.02 | 1.62-13.27 | 0.003 |

| Invisible ganglia | 8.84 | 2.11-23.32 | 0.001 |

| Invasion of celiac plexus | 7.83 | 1.81–15.77 | 0.009 |

| Distant metastasis | 4.90 | 1.32–17.91 | 0.394 |

| Injected alcohol dose | |||

| Procedure method | 2.87 | 0.44–17.41 | 0.502 |

| Unilateral | 0.54 | 0.16–1.99 | 0.093 |

| Bilateral | 0.94 | 0.42–3.12 | 0.858 |

| Intra-procedural decrease in heart rate |

CI: Confidence interval; EUS-CPN: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis; OR: Odds ratio; VAS: Visual analogue scale.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis for predictors affecting pain response after 4 wk by endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis

| Independent variables | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Invisible ganglia | 5.85 | 2.66-22.73 | 0.037 |

| Invasion of celiac plexus | 15.11 | 4.01-51.22 | 0.001 |

| Distant metastasis | 8.59 | 2.16–27.02 | 0.019 |

Summarizes the results of the multivariate analyses of the predictive factors associated with pain relief by EUS-CPN. The only independent predictive factors that achieved statistical significance in the univariate analysis were included. CI: Confidence interval; EUS-CPN: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis; OR: Odds ratio.

Complication after EUS-CPN

Complications occurred in 10.3% of enrolled patients. No serious adverse events including ischemic, inebriation, and acute paraplegia related to EUS-CPN occurred. Most of the complications were minor and transitory self-limited and included hypotension (1.7%), increase of pain (5.2%), and transient loose stools (3.4%).

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic cancer is often associated with intense and refractory pain. EUS-CPN was demonstrated to be safe and significantly improved pain control in 88% of patients with pancreatic cancer[16]. However, subsequent studies showed substantial variation in the proportion of patients experiencing pain relief[17]. This wide range is mainly attributable to differences in the characteristics of patients and the lack of standardized operation. For these reasons, it is difficult to compare the efficacy rate of EUS-CPN. Therefore, the current study was designed to analyze potential factors influencing EUS-CPN efficacy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Our data revealed that patients with invisible ganglia, distant metastasis, and invasion of the celiac plexus were predictors of less effective response in EUS-guided neurolysis for pancreatic cancer-related pain.

Our results demonstrated that invisible ganglia, presence of distant metastases, and celiac plexus invasion were significant negative variables at 1 wk and 4 wk after EUS-CPN by univariable analysis and multivariate regression analysis. The strongest predictor of response was celiac plexus invasion, which may be related to perineural invasion of pancreatic nerves by tumor cells. Direct invasion of the ganglia or plexus may result in patients with pain not mediated by the celiac plexus[1]. In fact, FNA of the celiac ganglia has confirmed invasion by malignant cells in some patients with pancreatic cancer[18]. The reason also may be that cancer invasion restricts the spread of neurolytic solution and limits the subsequent pain relief[19]. Iwata et al[20] also suggested that EUS-CPN seems to be less effective in patients with direct invasion of the celiac plexus.

There are mixed findings regarding bilateral or unilateral approach, and a recent meta-analysis showed that the short-term analgesic effect and general risk of bilateral EUS-CPN are comparable with those of unilateral EUS-CPN[9]. There were no differences in onset or duration of pain relief when either one or two injections were used[13,14,21]. In our cohort patients, the bilateral method was associated with a good pain response but no statistical significance (P = 0.087). With regard to the dose of alcohol used in EUS-CPN, the amount of alcohol used in EUS-CPN ranged from 2 mL to 20 mL[22-24]. Our results found that there was no difference in the dose of alcohol used in EUS-CPN, which is consistent with the results described by Leblanc et al[25]. Leblanc et al[25] indicated that similar clinical outcomes were seen in the 10 mL and 20 mL alcohol groups with respect to overall pain relief, weekly pain scores, onset of pain relief, and proportion of complete responders.

However, according to our data, tumors located at the body/tail predicted a better response than those with tumors at the pancreatic head/neck after 1 wk or 4 wk, although there were no significant differences (P = 0.094 and P = 0.082 L, respectively). This is in contrast to previous literature reports[26]. Ascunce et al[1] reported that tumors located outside the head of the pancreas were weakly associated with a good response. Rykowski et al[27] also reported that the posterior transcutaneous CPN technique was more effective in tumors involving the pancreatic head than in those affecting the body and tail of the pancreas. On the other hand, our finding was inconsistent with a previous study on heart rate change. Recently, Bang et al[28] discussed a direct correlation between the increase in heart rate during alcohol injection and treatment outcomes. They found that during EUS-CPN, the heart rate change cohort had significantly better adjusted scores for pain, financial difficulties, weight loss, and satisfaction with body image. Especially, a rise in heart rate during alcohol injection appeared to signal successful targeting of the celiac plexus and may be a simple predictor of treatment outcome. However, during alcohol injection in our cohort, the intra-procedural heart rate was decreased in ≥ 80% of patients. The heart rate always decreased when the alcohol was injected into the celiac plexus, and it returned to baseline level after several seconds.

Certainly, the present study has its inherent limitations that should be considered. First, the study is retrospective and the samples of patients are relatively small, suggesting restricted application of the results. A second limitation is the difficulty in measuring pain score, which was variable and a subjective measure. Finally, we failed to supply any results beyond 4 wk, because over time the efficacy of CPN decreased. Also, beyond 4 wk to 16 wk, there were fewer patients for analyzing these data. Therefore, we did not include these patients who received treatment more than 4 wk in the study (data not shown). We also could not compare the survival of patients who did CPN and those who did not. In order to evaluate objectively the significance of these parameters, a large group of multicenter, prospective, randomized trials are required.

CONCLUSION

Our study found that EUS-CPN is a safe and effective form of treatment for intractable pancreatic cancer-associated pain. EUS-CPN seems to be less effective in patients with invisible ganglia, distant metastasis, and direct invasion of the celiac plexus. For these patients, additional attention should be paid to efficacy.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) is widely used to treat pancreatic cancer-associated pain.

Research motivation

Response to the treatment of EUS-CPN is variable.

Research objectives

To explore determinants of pain response in EUS-CPN for pancreatic cancer-associated pain.

Research methods

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to explore predictors of pain response.

Research results

Invisible ganglia, metastatic disease, and invasion of the celiac plexus were identified as significant factors for a negative response to EUS-CPN. No severe adverse events were reported.

Research conclusions

Invisible ganglia, distant metastasis, and invasion of the celiac plexus were predictors of less effective response in EUS-CPN for pancreatic cancer-related pain. For these patients, attention should be given regarding efficacy.

Research perspectives

These findings could be helpful to endoscopists or oncologists to develop an appropriate treatment scheme for pain management in pancreatic cancer patients.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (IORG No: IORG0003571).

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: July 4, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Article in press: November 12, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kozarek RA, Thandassery RB S-Editor: Liu M (Part-Time Editor) L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Chao-Qun Han, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Xue-Lian Tang, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Qin Zhang, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Chi Nie, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Jun Liu, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Zhen Ding, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China. 2017xh0122@hust.edu.cn.

Data sharing statement

Dataset available from the corresponding author at 271914799@qq.com.

References

- 1.Ascunce G, Ribeiro A, Reis I, Rocha-Lima C, Sleeman D, Merchan J, Levi J. EUS visualization and direct celiac ganglia neurolysis predicts better pain relief in patients with pancreatic malignancy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minaga K, Takenaka M, Kamata K, Yoshikawa T, Nakai A, Omoto S, Miyata T, Yamao K, Imai H, Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Kudo M. Alleviating Pancreatic Cancer-Associated Pain Using Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Neurolysis. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10:50. doi: 10.3390/cancers10020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, Asbun H, Bain A, Behrman SW, Benson AB, Binder E, Cardin DB, Cha C, Chiorean EG, Chung V, Czito B, Dillhoff M, Dotan E, Ferrone CR, Hardacre J, Hawkins WG, Herman J, Ko AH, Komanduri S, Koong A, LoConte N, Lowy AM, Moravek C, Nakakura EK, O'Reilly EM, Obando J, Reddy S, Scaife C, Thayer S, Weekes CD, Wolff RA, Wolpin BM, Burns J, Darlow S. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:1028–1061. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg E, Carr DB, Chalmers TC. Neurolytic celiac plexus block for treatment of cancer pain: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:290–295. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagels W, Pease N, Bekkering G, Cools F, Dobbels P. Celiac plexus neurolysis for abdominal cancer pain: a systematic review. Pain Med. 2013;14:1140–1163. doi: 10.1111/pme.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy MJ, Gleeson FC, Topazian MD, Fujii-Lau LL, Enders FT, Larson JJ, Mara K, Abu Dayyeh BK, Alberts SR, Hallemeier CL, Iyer PG, Kendrick ML, Mauck WD, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Rajan E, Takahashi N, Vege SS, Wang KK, Chari ST. Combined Celiac Ganglia and Plexus Neurolysis Shortens Survival, Without Benefit, vs Plexus Neurolysis Alone. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 728-738. :e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koulouris AI, Banim P, Hart AR. Pain in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer: Prevalence, Mechanisms, Management and Future Developments. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:861–870. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4488-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda I, Wang HP. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block and neurolysis. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:455–462. doi: 10.1111/den.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu F, Dong J, Tang Y, Huang H, Liu H, Song L, Zhang K. Bilateral vs. unilateral endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for abdominal pain management in patients with pancreatic malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:353–359. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyse JM, Battat R, Sun S, Saftoiu A, Siddiqui AA, Leong AT, Arturo Arias BL, Fabbri C, Adler DG, Santo E, Kalaitzakis E, Artifon E, Mishra G, Okasha HH, Poley JW, Guo J, Vila JJ, Lee LS, Sharma M, Bhutani MS, Giovannini M, Kitano M, Eloubeidi MA, Khashab MA, Nguyen NQ, Saxena P, Vilmann P, Fusaroli P, Garg PK, Ho S, Mukai S, Carrara S, Sridhar S, Lakhtakia S, Rana SS, Dhir V, Sahai AV. Practice guidelines for endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:369–375. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_97_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyse JM, Carone M, Paquin SC, Usatii M, Sahai AV. Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of early endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis to prevent pain progression in patients with newly diagnosed, painful, inoperable pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3541–3546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doi S, Yasuda I, Kawakami H, Hayashi T, Hisai H, Irisawa A, Mukai T, Katanuma A, Kubota K, Ohnishi T, Ryozawa S, Hara K, Itoi T, Hanada K, Yamao K. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac ganglia neurolysis vs. celiac plexus neurolysis: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2013;45:362–369. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Téllez-Ávila FI, Romano-Munive AF, Herrera-Esquivel Jde J, Ramírez-Luna MA. Central is as effective as bilateral endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Endosc Ultrasound. 2013;2:153–156. doi: 10.7178/eus.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBlanc JK, Al-Haddad M, McHenry L, Sherman S, Juan M, McGreevy K, Johnson C, Howard TJ, Lillemoe KD, DeWitt J. A prospective, randomized study of EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for pancreatic cancer: one injection or two? Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1300–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Si-Jie H, Wei-Jia X, Yang D, Lie Y, Feng Y, Yong-Jian J, Ji L, Chen J, Liang Z, De-Liang F. How to improve the efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis in pain management in patients with pancreatic cancer: analysis in a single center. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:31–35. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiersema MJ, Wiersema LM. Endosonography-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:656–662. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puli SR, Reddy JB, Bechtold ML, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for pain due to chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer pain: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2330–2337. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy MJ, Topazian M, Keeney G, Clain JE, Gleeson F, Rajan E, Wang KK, Wiersema MJ, Farnell M, Chari S. Preoperative diagnosis of extrapancreatic neural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1479–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Cicco M, Matovic M, Bortolussi R, Coran F, Fantin D, Fabiani F, Caserta M, Santantonio C, Fracasso A. Celiac plexus block: injectate spread and pain relief in patients with regional anatomic distortions. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:561–565. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwata K, Yasuda I, Enya M, Mukai T, Nakashima M, Doi S, Iwashita T, Tomita E, Moriwaki H. Predictive factors for pain relief after endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:140–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahai AV, Lemelin V, Lam E, Paquin SC. Central vs. bilateral endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block or neurolysis: a comparative study of short-term effectiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:326–329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Wiersema MJ, Clain JE, Rajan E, Wang KK, de la Mora JG, Gleeson FC, Pearson RK, Pelaez MC, Petersen BT, Vege SS, Chari ST. Initial evaluation of the efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided direct Ganglia neurolysis and block. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Kamata K, Komaki T, Imai H, Chikugo T, Takeyama Y, Kudo M. EUS-guided broad plexus neurolysis over the superior mesenteric artery using a 25-gauge needle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2599–2606. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunaratnam NT, Sarma AV, Norton ID, Wiersema MJ. A prospective study of EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for pancreatic cancer pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:316–324. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leblanc JK, Rawl S, Juan M, Johnson C, Kroenke K, McHenry L, Sherman S, McGreevy K, Al-Haddad M, Dewitt J. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Celiac Plexus Neurolysis in Pancreatic Cancer: A Prospective Pilot Study of Safety Using 10 mL vs 20 mL Alcohol. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2013;2013:327036. doi: 10.1155/2013/327036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minaga K, Kitano M, Sakamoto H, Miyata T, Imai H, Yamao K, Kamata K, Omoto S, Kadosaka K, Sakurai T, Nishida N, Chiba Y, Kudo M. Predictors of pain response in patients undergoing endoscopic ultrasound-guided neurolysis for abdominal pain caused by pancreatic cancer. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:483–494. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16644248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rykowski JJ, Hilgier M. Efficacy of neurolytic celiac plexus block in varying locations of pancreatic cancer: influence on pain relief. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:347–354. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bang JY, Hasan MK, Sutton B, Holt BA, Navaneethan U, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Intraprocedural increase in heart rate during EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis: Clinically relevant or just a physiologic change? Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:773–779.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available from the corresponding author at 271914799@qq.com.