Abstract

Background and Aims

Facilitation is an important ecological process for plant community structure and functional composition. Although direct facilitation has accrued most of the evidence so far, indirect facilitation is ubiquitous in nature and it has an enormous potential to explain community structuring. In this study, we assess the effect of direct and indirect facilitation on community productivity via taxonomic and functional diversity.

Methods

In an alpine community on the Tibetan Plateau, we manipulated the presence of the shrub Dasiphora fruticosa and graminoids in a fenced meadow and a grazed meadow to quantify the effects of direct and indirect facilitation. We measured four plant traits: height, lateral spread, specific leaf area (SLA) and leaf dry matter content (LDMC) of forbs; calculated two metrics of functional diversity [range of trait and community-weighted mean (CWM) of trait]; and assessed the responses of functional diversity to shrub facilitation. We used structural equation modelling to explore how shrubs directly and indirectly drove community productivity via taxonomic diversity and functional diversity.

Key Results

We found stronger effects from herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation than direct facilitation on productivity and taxonomic diversity, regardless of the presence of graminoids. For functional diversity, the range and CWM of height and SLA, rather than lateral spread and LDMC, generally increased due to direct and indirect facilitation. Moreover, we found that the range of traits played a primary role over taxonomic diversity and CWM of traits in terms of shrub effects on community productivity.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that the mechanism of shrub direct and indirect facilitation of community productivity in this alpine community is expanding the realized niche (i.e. expanding range of traits). Our findings indicate that facilitators might increase trait dispersion in the local community, which could alleviate the effect of environmental filters on trait values in harsh environments, thereby contributing to ecosystem functioning.

Keywords: Community productivity, community-weighted mean, Dasiphora fruticosa, direct facilitation, functional diversity, indirect facilitation, trait range

INTRODUCTION

Plant community structure and composition have traditionally been shown to be substantially influenced by negative plant–plant interactions, i.e. competition (Grime, 1974; Tilman, 1982). Over the last two decades, the importance of positive interactions (i.e. facilitation) for community response has been well established (Callaway et al., 2002; McIntire and Fajardo, 2014). For instance, in alpine meadows, facilitation increases community richness and Shannon diversity (Cavieres et al., 2014, 2016) by alleviating stressful conditions, which has been widely reported (Bruno et al., 2003; Brooker et al., 2008). Moreover, facilitation has been shown to affect the functional diversity (a functional component of biodiversity that concerns the distribution of species in a functional space; Rosenfeld, 2002; Petchey and Gaston, 2006) of plant communities (Butterfield and Callaway, 2013), particularly by alleviating stressful conditions, and thus facilitation can expand the realized niche of associated species (Bulleri et al., 2016). For example, at an alpine site in Australia, Ballantyne and Pickering (2015) found that the nurse shrub Epacris gunnii supported more species that were taller and had larger leaves than those from open areas. Liancourt et al. (2005) showed in calcareous grasslands that competitive species were more facilitated than stress-tolerant species. This is because competitive species with greater heights and leaf areas have a greater ability to tolerate shading by neighbours and thus obtain a greater benefit from physical stress alleviation. These results suggest that nurse plants may support understorey communities, including species with specific traits and functional strategies (Dolezal et al., 2019). Although we have begun to understand the role of facilitation for, on the one hand, taxonomic diversity and, on the other hand, functional diversity, whether and how facilitation affects productivity via changes in taxonomic diversity and functional diversity of a plant community are still poorly understood.

Facilitation can be divided into two types: direct facilitation and indirect facilitation. The former refers to a neighbouring plant directly improving the performance of a target plant community by ameliorating environmental conditions, while the latter refers to direct interactions among species via shared plant competitors (e.g. competition release; Levine, 1999; Xiao and Michalet, 2013) or an animal (e.g. associational resistance; Callaway et al., 2005), with important consequences for community composition and diversity (Aschehoug and Callaway, 2015). Schöb et al. (2012) showed that the direct facilitation of the alpine cushion species Arenaria tetraquetra altered the functional diversity of its associated communities, particularly through a trait range expansion of lateral spread, specific leaf area (SLA) and leaf dry matter content (LDMC) due to relaxation of the environmental filter. Levine (1999) argued that indirect facilitation among plant species due to competition release is more likely to occur when the different partners compete for different resources or interfere through different mechanisms. Since the ability to acquire different resources within plant communities is related to specific traits and the functional strategies of particular species, in comparison with direct facilitation, indirect facilitation due to competition release might be expected to alter functional diversity in different ways. Additionally, the effects of herbivores differ from the effects of a plant competitor. Thus, indirect facilitation due to protection against grazing may alter the functional diversity of plant communities in a different way from indirect facilitation due to competition release (Callaway et al., 2005; Anthelme and Michalet, 2009; Danet et al., 2018). For example, the former type of indirect facilitation may favour tall species more likely to be eaten by herbivores (Danet et al., 2017), whereas the latter type may favour species with exploitative strategies (e.g. high SLA) demanding increasing resources, as shown by Pagès et al. (2003) in forest communities. Overall, different alterations in functional diversity by the different types of facilitation may translate into different effects on community productivity.

To assess how direct and indirect facilitation of a dominant shrub species affects the productivity of an alpine plant community through changes in taxonomic diversity and functional diversity, we conducted an experiment in an alpine meadow dominated by the shrub Dasiphora fruticosa (L.) Rydb. (family: Rosaceae) on the eastern Tibetan Plateau (China). Michalet et al. (2015a) have shown in a similar ecosystem located in the sub-alpine belt that forb species had contrasting responses to both direct and indirect effects (due to the presence of graminoids) of D. fruticosa that ultimately influenced community composition. Additionally, Wang et al. (2019) assessed, at the alpine belt and under ungrazed conditions, how the direct and indirect (due to the presence of graminoids) effects of D. fruticosa on forb species might be predicted from forb species trait values. However, none of these studies assessed how direct and indirect facilitation of D. fruticosa affects the productivity of forb communities through changes in taxonomic diversity and functional diversity. Such information may improve our understanding of the role of a dominant shrub in mediating the biodiversity–productivity relationship and may also enable the prediction of how a given plant community will respond to shrub colonization during successional changes.

In this study, we manipulated the presence of D. fruticosa in the presence and absence of graminoids and in both fenced and grazed meadows to assess variation in forb productivity across treatments. We used forb biomass as a proxy of plant community productivity since relative differences in biomass across treatments within our system were due to differences in productivity We also quantified the taxonomic diversity and functional diversity of the forb communities and used structural equation modelling (SEM) to answer the following questions. (1) Is indirect facilitation (graminoid-mediated, herbivore-mediated and graminoid–herbivore-mediated) more important than direct facilitation for forb community biomass and taxonomic diversity (i.e. richness and Shannon diversity)? (2) Do shrubs directly or indirectly affect the functional diversity of forb communities? (3) How do shrubs directly and indirectly impact community productivity via changes in taxonomic diversity and functional diversity?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site

Our experiment was conducted at the Research Station of the Alpine Meadow and Wetland Ecosystems of Lanzhou University (Azi Branch Station) in Maqu (101°51′E, 33°40′N), Gansu, China. The experimental site is located in a relatively flat alpine meadow of the eastern Tibetan Plateau at 3500 m above sea level. The climate is continental, with a mean monthly temperature ranging from –10 °C in January to 11.7 °C in July and a mean annual temperature of 1.2 °C. The annual precipitation (620 mm) measured over the last 35 years falls mainly during the short, cool summer. The vegetation in this area includes the shrub D. fruticosa, grasses and sedges (hereafter ‘graminoids’), mainly Kobresia capillifolia, Elymus nutans, Agrostis hugoniana, Agrostis trinii, Festuca ovina and Poa poophagorum, associated with a high number of forb species. The study area has been exposed to continuous overgrazing by yaks at a density of 1.6 head hm–2 since 1999, with a low density of other small mammals, such as Ochotona curzoniae and Marmota spp.

Experimental design

An area (35 × 35 m) in the alpine meadow including >250 shrub individuals of D. fruticosa was fenced with barbed wire in 2014. In early June 2015, we randomly selected 60 shrubs of similar size (Supplementary data Table S1) inside and outside the fenced meadow. These shrubs in each meadow (i.e. fenced and grazed) were randomly assigned to one of four treatments: shrub with graminoids (control plots), shrub without graminoids, without shrub with graminoids, and without shrub without graminoids. All initial dead plant material was removed from the plots. There was no re-sprouting of shrubs that were removed during the experiment, but the above-ground parts of the graminoids were removed every 2 weeks. We left the roots of the graminoids in the ground, as the effects of the roots of the graminoids can be considered minimal when their canopy is removed, and removing roots may create strong confounding effects due to disturbance. At the end of the growing season (the end of August 2015), the above-ground parts of every forb were collected in 30 × 30 cm quadrats placed in the centre of each shrub and oven-dried for 3 d at 80 °C before weighing, and this material was used to calculate the relative interaction index and community-weighted mean (CWM) of each trait.

Our study site was located at a relatively even meadow colonized by D. fruticosa. Although we know that focusing on a limited study area (35 × 35 m in fenced and grazed meadows) might result in potential limitations in the representativeness of our sampling, replicating the whole field enclosure was not possible in our study.

Biotic interaction indices

The relative interaction index (RII) was used to quantify the effects of D. fruticosa and graminoids on forbs (Armas et al., 2004):

where X+N and X-N are the three indices (i.e. biomass, richness and Shannon diversity) of the forb community in the presence or absence of dominant neighbours (N; i.e. shrubs or graminoids), respectively. Note that all the biomass (i.e. biomass of leaves for SLA and all species in each plot) from the plots were used to calculate the RII. The index is symmetrical around 0 (no significant interaction) and varies between +1 (facilitation) and –1 (competition).

To quantify the direct and indirect effects of the shrubs on the three indices of the forb community, four RIIs with different ecological meanings (i.e. direct facilitation of the shrub, graminoid-mediated indirect facilitation, herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation and graminoid- and herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation) were calculated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Formulae and ecological meanings of the four RIIs, their type (i.e. direct or indirect RIIs), name and calculation according to the formula of Armas et al. (2004), as the relative difference in the performances of forbs between treatments.

| Type | Name | Calculations | Ecological meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct RII | RIIShrub | Shrub without graminoids and without shrub without graminoids (Fenced) | Direct facilitation of the shrub |

| Indirect RII | RIIShrub + gram | Shrub with graminoids and without shrub with graminoids (Fenced) | Graminoid-mediated indirect facilitation |

| Indirect RII | RIIShrub + herbi | Shrub without graminoids and without shrub without graminoids (Grazed) | Herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation |

| Indirect RII | RIIShrub + gram + herbi | Shrub with graminoids and without shrub with graminoids (Grazed) | Graminoid and herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation |

Functional traits

Four functional traits characterizing both plant stature and the leaf economic spectrum were used to assess forb functional diversity, as these traits have been shown to be strongly relevant to addressing the effects of plant–plant interactions on plant strategies (also shown in the Introduction), and these traits were plant height (cm), lateral spread (cm), SLA (the ratio of leaf area to dry mass, cm2 g–1) and LDMC (the ratio of leaf dry mass to leaf fresh mass, g g–1). Plant height (extreme reproductive boundary) was the distance between the extended upper boundary of the plant and the ground level when an individual was straightened. Plant lateral spread (cm) was determined as the maximum diameter of an individual or ramet in the case of clonal plants, which were very rare. For calculating SLA and LDMC, one mature and healthy leaf per individual was selected to measure the fresh weight as well as leaf area (LA, cm2) by using ImageJ software within 6 h (Abramoff et al., 2004). Then, dry weight was quantified after drying for 3 d at 80 °C in an oven. We measured all traits on three individuals of each species, excluding species with fewer than three individuals in each plot.

Functional diversity was indicated by the range and CWM of each trait in our study. In each plot, two limits (lower and upper) of the trait distribution values were used to calculate trait range (upper limit minus lower limit) in each forb community, while the CWM of each trait was calculated in each forb community according to Lavorel et al. (2008).

where pi is the relative abundance of species i (i = 1, 2, …, S) and xi is the mean trait value for species i.

Statistical analyses

Non-parametric 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) of RIIs were calculated by bootstrap sampling with 999 iterations (Kirby and Gerlanc, 2013). An RII is statistically significant when the boot-strapped 95 % CI does not overlap zero (i.e. positive or negative RIIs) and is statistically distinct from other RIIs when the 95 % CI does not overlap, indicating an indirect effect due to the presence of graminoids following Michalet et al. (2015b). We used one-sample t-tests to test for significant shrub effects (i.e. difference between treatments from zero value) on the range and CWM of each trait. A significant sample t-test on the range and CWM of a trait indicated a range expansion or contraction and a CWM shift, respectively.

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was applied to assess how taxonomic diversity and functional diversity mediated the effects of the shrubs on community productivity in the fenced and grazed plots, separately. We chose to run SEM only on plots without graminoids and for the shrub effect for simplification and because the addition of graminoids weakly affected both taxonomic diversity and forb traits, particularly in the grazed plots, compared with the much stronger effects of the shrub and grazing treatments.

We conducted SEM analyses according to an a priori model (Supplementary data Fig. S1) with the following premises: we hypothesized that (1) the presence of shrub D. fruticosa could affect taxonomic diversity (i.e. richness and Shannon diversity) and functional diversity (i.e. range and CWM of traits) by ameliorating the environment and offsetting the environmental filter (Schöb et al., 2012); and (2) shrubs either directly or indirectly could affect the community’s biomass via changes in taxonomic diversity and functional diversity (i.e. diversity–productivity relationship; Tilman et al., 1997).

We used a combination of the Bollen–Stine bootstrapping test and comparative fit index (CFI) to assess the goodness of fit of the SEM. A non-significant Bollen–Stine bootstrapping test and CFI >0.90 indicated a good fit of the model to the data (Kline, 2011).

All data were analysed using R software, ver. 3.3.3 (R Core Team, 2017). CI was calculated with the ‘bootES’ package (Kirby and Gerlanc, 2013), CWM was calculated with the ‘FD’ package (Laliberté et al., 2014) and SEM was performed with the ‘lavaan’ package (Rosseel, 2012).

RESULTS

Importance of indirect facilitation due to the shrub canopy (objective 1)

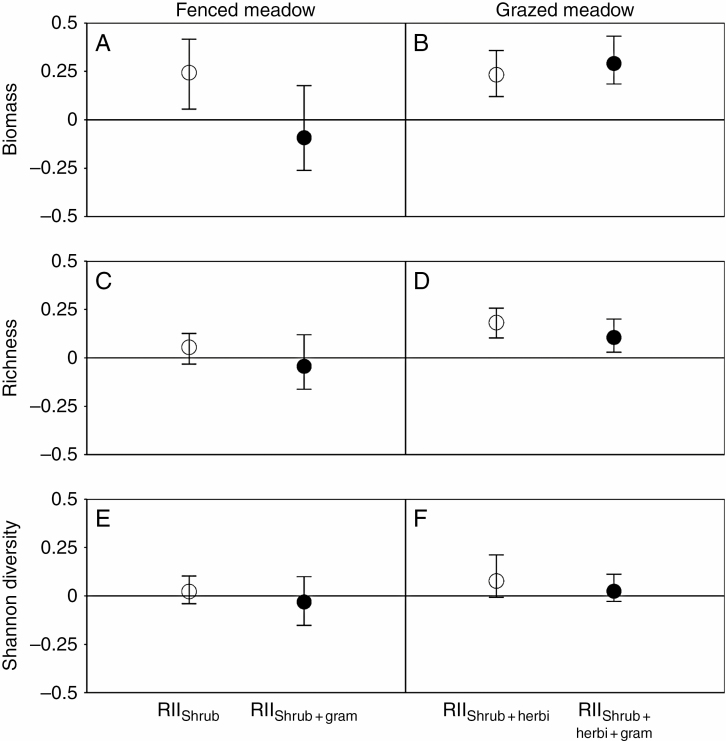

In the fenced meadow, the biomass of the forbs was increased (i.e. positive RIIShrub) by the shrubs, i.e. evidence of direct facilitation (Fig. 1A). However, there was no significant graminoid-mediated indirect facilitation (i.e. neutral RIIShrub + gram; Fig. 1A). In the grazed meadow, the shrubs also increased the biomass of the forbs in the absence of graminoids, i.e. evidence of herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation (i.e. positive RIIShrub + herbi; Fig. 1B). The presence of graminoids had no effect on the indirect RII for biomass in the grazed meadow (i.e. RIIShrub + herbi + gram; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Four RIIs for forb biomass (A and B), richness (C and D) and Shannon diversity (E and F) in the fenced and grazed meadows, respectively. An RII is statistically significant when the bootstrapped 95 % CI does not overlap the solid line of zero, and is statistically distinct from other RIIs when the 95 % CI does not overlap.

For richness, neither direct nor indirect RIIs were significantly different from zero in the fenced meadow (Fig. 1C). In contrast, in the grazed meadow, positive shrub effects on richness were observed in the absence of graminoids, as was observed for biomass, i.e. evidence of herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation (Fig. 1D). The presence of graminoids had no effect on the indirect RII for richness in the grazed meadow (Fig. 1D).

Forb Shannon diversity was not affected by the presence of shrubs and graminoids in the fenced meadow; it slightly increased but was still not significant due to the presence of the shrubs in the grazed meadow (Fig. 1E, F).

Direct and indirect shrub effects on forb traits (objective 2)

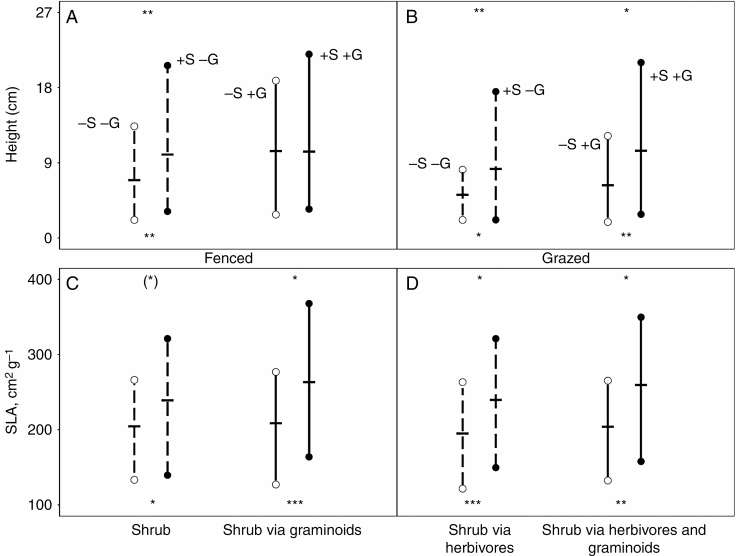

There were strong effects of shrubs on the height and SLA of the forb communities, both with and without graminoids (Fig. 2), whereas lateral spread and LDMC were less affected by shrubs and graminoids (Supplementary data Fig. S2). In the fenced meadow, the range and CWM of height and SLA both increased under the direct effects of the shrubs (Fig. 2A, C), consistent with the direct facilitation observed for biomass (Fig. 1A). In contrast, in the presence of graminoids, shrub effects were only observed for SLA, and mostly for CWM, but not for height, and this latter result was consistent with the non-significant RIIShrub + gram for biomass formerly observed in the fenced meadow (Fig. 1A). In contrast, in the grazed meadow, the presence of shrubs, regardless of the presence of graminoids, expanded the range and increased the CWM of height (Fig. 2B), which was consistent with the strong indirect facilitation of shrubs observed for biomass and richness in the presence of herbivores, regardless of the presence of graminoids (Fig. 1B, D). The same effects of shrubs were observed, both with and without graminoids, for the range and CWM of SLA (Fig. 2D). Overall, the effects of shrubs on lateral spread were very weak, whereas those for LDMC were similar to those observed for SLA in the grazed meadow (Supplementary data Fig. S2a, b).

Fig. 2.

Mean trait range (n = 15; vertical line) and CWM (n = 15; horizontal lines) of height (A and B) and specific leaf area (SLA; C and D) in the absence (open circle) and presence (filled circle) of shrubs in the fenced (A and C) and grazed meadows (B and D). Direct shrub effects and shrub effects via herbivores (i.e. without graminoids) on trait range and CWM are shown by differences between dashed lines, whereas shrub effects via graminoids and shrub effects via herbivores and graminoids are indicated by differences between solid lines. Asterisks at the bottom of each set of lines indicate significant changes in the CWM of the trait due to the effects of the shrub from t-tests, and ‘+’ at the top of each set of lines indicates significant changes in trait range due to the effects of the shrub from t-tests. (*)/(+), P < 0.1; */+, P < 0.05; **/++, P < 0.01; ***/+++, P < 0.001. Treatments for assessing shrub effects are shown, ‘–S –G’, without shrub without graminoids; ‘+S –G’, with shrub without graminoids; ‘–S +G’, without shrub with graminoids; ‘+S +G’, with shrub with graminoids.

Mediating role of functional diversity in shrub facilitation effects (objective 3)

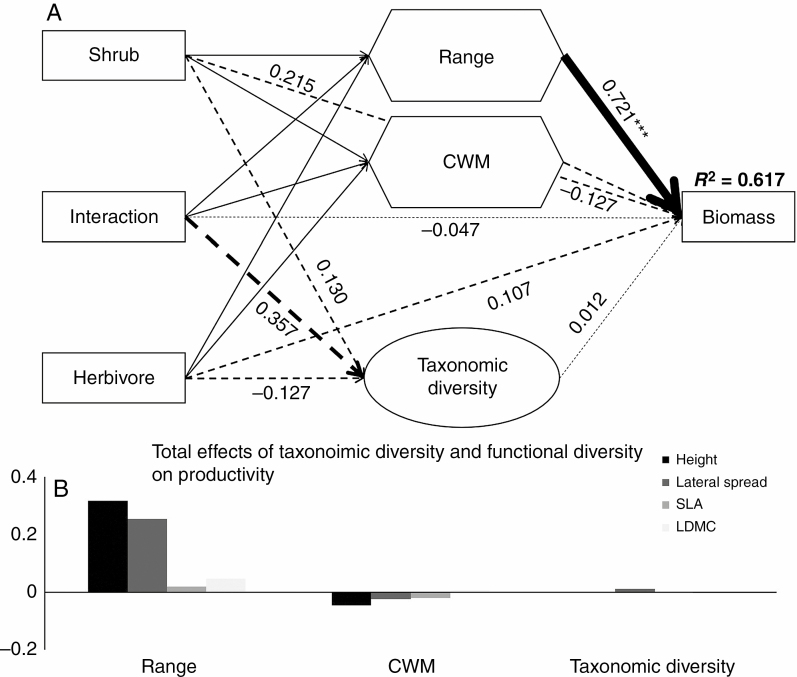

The SEM assessing the influences of shrubs and herbivores and their interaction on community biomass explained 61.7 % of the variation (Fig. 3). When including both direct and indirect effects, the range of traits was the most important driver controlling community biomass in our study (Fig. 3). Interestingly, neither shrubs, herbivores nor their interactions directly affected community biomass, whereas they indirectly affected community biomass via a range of traits (Fig. 1; Supplementary data Table S2). Specifically, shrubs showed consistently positive effects on community biomass by increasing the range of traits, particularly height and lateral spread (Supplementary data Table S2), indicating that there were consistently positive effects of direct and herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation on community biomass. In contrast, herbivores and interactions only had limited impacts on community biomass (Fig. 3A; Supplementary data Table S2). Overall, the total effects from the SEM indicated that the range of traits was more important than the taxonomic diversity and CWM of traits in explaining changes in biomass due to shrub facilitation (Fig. 3B). Specifically, the larger the trait range was, the better the biomass of the forb community.

Fig. 3.

Structural equation modelling of the shrub (A) by herbivore effects and total (B) effects of range and CWM of each trait (in the absence of graminoids) on the biomass of forb communities. d.f. = 35, PBollen-Stine Bootstrap = 0.213, CFI = 0.923. Rectangular boxes are treatment variables, range (a composite variable of height range, lateral spread range, SLA range and LDMC range) and CWM (a composite variable of CWMheight, CWMlateral spread, CWMSLA and CMWLDMC) in hexagons are composite variables, and the ellipse is a latent variable that is indicated by richness and Shannon diversity of the forb community. Black solid arrows indicate a significant effect (at the level P < 0.05), and black dashed arrows indicate a non-significant effect (at the level P > 0.05). Values associated with solid arrows represent standardized path coefficients, which are also indicated by arrow width. Detailed effects of shrubs, herbivores and their interactions on the two composite variables are shown in Supplementary data Table S2. R2 values associated with response variables indicate the proportion of explained variation by relationship with other variables. ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

In response to our first question, we found that the predominant effect of the shrub D. fruticosa on forb community productivity was positive and indirect through a reduction in the negative effects of herbivory, regardless of the presence of graminoids. In response to our second question, in the absence of herbivores, we found strong effects of facilitation on height and SLA. In the presence of herbivores, the effect of facilitation on these two traits was strongly positive, both with and without graminoids. In response to our third question, we found that changes in the functional diversity of forbs mediated the direct and herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation of shrubs on forb community productivity. Specifically, the range of traits played a more important role than the taxonomic diversity and CWM of traits in explaining the effects of shrub facilitation on forb community productivity.

Importance of indirect facilitation of shrubs against grazers (question 1)

In herbaceous systems, indirect facilitation by protection against grazing has been shown to be more important than direct facilitation in productive communities, such as in the grazed meadows of mountain and sub-alpine belts from temperate climates (Callaway et al., 2005, 2007; Schöb et al., 2010; but see evidence of indirect facilitation in several unfertile dry systems in Soliveres et al., 2011; Verwijmeren et al., 2019). In contrast, in high alpine communities, as in our study, direct facilitation is the dominant interaction, and evidence of indirect facilitation by protection against grazing is rare; to date, it has only been documented in tropical peatlands (Danet et al., 2017, 2018). This scenario is consistent with the model of Bertness and Callaway (1994), which predicts that the frequency of indirect facilitation should increase with community productivity due to increasing grazing pressure and, conversely, that the intensity of direct facilitation should increase with increasing physical stress and physical disturbance (but see Anthelme and Michalet, 2009). In our system, the higher importance of herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation than direct facilitation found for biomass, richness and Shannon diversity was probably due to the high specificity of the Tibetan Plateau, with very deep soils originating from aeolian silt deposition increasing soil fertility and thus grazing disturbance (Lehmkuhl et al., 2000). In contrast, soils are very shallow, and productivity is very low in alpine systems on other continents (Kikvidze et al., 2011).

In the absence of herbivores, there was also direct facilitation of the shrubs on forb biomass only, but the presence of graminoids reduced this effect. This negative indirect effect disappeared in the grazed meadow because graminoids facilitated the forbs in the opening of the fenced meadow only (total forb biomass: 6.44 g in ‘without shrub with graminoids’ treatment vs. 3.43 g in ‘without shrub without graminoids’ treatment). Overall, only weak indirect effects were observed for biomass in the fenced meadow, while there was no significant graminoid effect for either forb richness or composition in the two meadows. Wang et al. (2019) also found weakly significant indirect facilitation due to competition release at the same site in the fenced meadow, while they did not assess interactions in the grazed meadow.

Direct and indirect shrub effects on forb traits (question 2)

In the fenced meadow, a positive direct effect of the shrubs on the functional diversity of the forb community was observed for both the range and CWM of three traits, i.e. height, SLA and lateral spread. Schöb et al. (2012) found that the presence of short alpine cushion nurse species increased CWM and expanded the trait range of SLA and decreased the LDMC of understorey species, probably through an amelioration of soil resources, in particular water availability, at their Mediterranean alpine site. In our study, increases in CWM and expansions of trait ranges of the forb community are more likely to have been due to an amelioration of atmospheric water stress and a decrease in photoinhibition with decreasing light intensity below the canopy of the shrub (Germino et al., 2002; Anthelme and Michalet, 2009). Although light competition is known to also increase the height and SLA of shaded plants (Reich et al., 1998), light competition is unlikely to have induced these changes in functional diversity in our system since facilitation also occurred for the biomass of the forbs. Additionally, the effect of facilitation is generally stronger for understorey species which are tall and have large leaf size (Falster and Westoby, 2003; Liancourt et al., 2005; Rolhauser and Pucheta, 2016) because the cost of shading for light is lower and its benefit for stress mitigation is higher for stress-intolerant competitive species sensuGrime (1974); species of this strategy are thus very likely to have increased in abundance below the shrubs. The positive effect of the shrubs on height disappeared in the fenced plots in the presence of graminoids, which suggests that the effect of graminoids on light and microclimate was similar in the absence of shrubs to the effect of shrubs without graminoids. In contrast, this effect remains for SLA, which suggests that graminoids did not increase the SLA of forbs in the absence of shrubs.

In the grazed meadow, the effect of shrubs on the range and CWM of height and SLA of forbs was strong and consistent, regardless of the presence of graminoids. The higher strength of these effects on functional diversity in the grazed meadow than in the fenced meadow was likely to be due to higher shrub protection against grazing for tall plants with palatable leaves than for other species strategies (Callaway et al., 2005; Danet et al., 2018). The absence of indirect effects due to the addition of graminoids showed that in contrast to the fenced meadow, graminoids had no protective effect on forb height in the absence of shrubs.

Different roles of taxonomic diversity and functional diversity in shrub facilitation effects (question 3)

Changes in the taxonomic diversity and functional diversity of forbs mediated the direct and herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation of shrubs on community productivity. These results are novel since, to our knowledge, the mediating role of taxonomic diversity and functional diversity in facilitative effects on community productivity has been addressed only for the traits of the benefactors, particularly at the intraspecific level, but not for the traits of the understorey species (Schöb et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2018). There has also been an increase in interest in better understanding the role of the main ecological filters of community assembly, such as biotic interactions and environmental conditions, in driving the functional diversity of plant communities (De Bello et al., 2012; Le Bagousse-Pinguet et al., 2017; Danet et al., 2018). However, to our knowledge, no study has assessed the entire chain of relationships existing between direct and indirect interactions of community dominants, the taxonomic diversity and functional diversity of species and community productivity.

In our study, the range of traits was more important than the taxonomic diversity and CWM of traits in driving forb community productivity. Specifically, direct and herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation of shrubs on community productivity was mainly due to the expansion of the range of all traits. This result indicates that the higher biomass of the community resulted from a larger range of traits, which can be explained by the alleviation of environmental filters and expansion of the realized niche (Bruno et al., 2003) because, in comparison with the control, shrubs protected more species/individuals with higher trait values. Moreover, the large contribution of the range of height and lateral spread to community response indicates that the effect of facilitation on community response was mainly due to the recruitment of competitive species. Although we know that the best candidates for facilitation are competitive species (Liancourt et al., 2005), this is the first study to show how facilitation impacts the understorey community by recruiting competitive species. Overall, our results indicated that the impacts of facilitation on community productivity mainly resulted from alleviating environmental filters and supporting competitive species, as shown by the higher mediated effects of range than of the CWM of traits and the large contribution of height and lateral spread in our study; thus, our study substantially contributes to revealing the mechanism of facilitation.

Conclusions

Our study revealed the effect of direct and indirect shrub facilitation on the understorey community. Specifically, herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation increased community productivity, richness, range and CWM of height, and SLA. Although direct facilitation also increased community productivity, range and CWM of height, and SLA, the strength of direct facilitation was generally weaker than that of herbivore-mediated indirect facilitation. More importantly, we found that shrub facilitation affected understorey species’ productivity by changing functional diversity, i.e. mainly expanding the range of traits. Our findings have important consequences on how we think environmental filters act on the dispersion of functional trait values when facilitation exists, i.e. the effects of an environmental filter on functional trait values (i.e. convergence) might be alleviated by facilitators in the local community as a result of the expansion of the realized niche of the facilitated species (i.e. divergence). Moreover, the effect of facilitators on trait values can affect ecosystem functioning, i.e. the expanded realized niche of facilitated species contributes to increasing community productivity in harsh environments.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: mean shrub size in eight treatments. Table S2: standardized path coefficients and corresponding P-values of the SEM. Figure S1: a priori SEM model evaluating shrub by herbivore effects on forb community response via range and CWM of four traits in this study. Figure S2: mean trait range and CWM of lateral spread and leaf dry matter content in the absence and presence of shrubs in the fenced and grazed meadows.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Research Station of Alpine Meadow and Wetland Ecosystems of Lanzhou University for permission to use their site. Author contributions: X.W. and RM conceived and designed the experiments; G.D., X.Z. and S.X. helped with the design; X.W. and L.M. performed the experiments; X.W. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; R.M., S.C. and S.X. helped revise the manuscript; and all authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication. Conflict of interest: the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors declare no competing financial and non-financial interests.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41830321, 31870412, 32071532, 31670435, 31670437, 41671038, 31770448) and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) Program (2019QZKK0302).

LITERATURE CITED

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. 2004. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International 11: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Anthelme F, Michalet R. 2009. Grass-to-tree facilitation in an arid grazed environment (Aïr Mountains, Sahara). Basic Applied Ecology 10: 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Armas C, Ordiales R, Pugnaire FI. 2004. Measuring plant interactions: a new comparative index. Ecology 85: 2682–2686. [Google Scholar]

- Aschehoug ET, Callaway RM. 2015. Diversity increases indirect interactions, attenuates the intensity of competition, and promotes coexistence. The American Naturalist 186: 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne M, Pickering CM. 2015. Shrub facilitation is an important driver of alpine plant community diversity and functional composition. Biodiversity and Conservation 24: 1859–1875. [Google Scholar]

- de Bello F, Price JN, Münkemüller T, et al. 2012. Functional species pool framework to test for biotic effects on community assembly. Ecology 93: 2263–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertness MD, Callaway R. 1994. Positive interactions in communities. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 9: 191–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RW, Maestre FT, Callaway RM, et al. 2008. Facilitation in plant communities: the past, the present, and the future. Journal of Ecology 96: 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno JF, Stachowicz JJ, Bertness MD. 2003. Inclusion of facilitation into ecological theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18: 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bulleri F, Bruno JF, Silliman BR, Stachowicz JJ. 2016. Facilitation and the niche: implications for coexistence, range shifts and ecosystem functioning. Functional Ecology 30: 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield BJ, Callaway RM. 2013. A functional comparative approach to facilitation and its context dependence. Functional Ecology 27: 907–917. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM, Brooker RW, Choler P, et al. 2002. Positive interactions among alpine plants increase with stress. Nature 417: 844–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM, Kikodze D, Chiboshvili M, Khetsuriani L. 2005. Unpalatable plants protect neighbors from grazing and increase plant community diversity. Ecology 86: 1856–1862. [Google Scholar]

- Cavieres LA, Brooker RW, Butterfield BJ, et al. 2014. Facilitative plant interactions and climate simultaneously drive alpine plant diversity. Ecology Letters 17: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavieres LA, Hernández-Fuentes C, Sierra-Almeida A, Kikvidze Z. 2016. Facilitation among plants as an insurance policy for diversity in Alpine communities. Functional Ecology 30: 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Danet A, Anthelme F, Gross N, Kéfi S. 2018. Effects of indirect facilitation on functional diversity, dominance and niche differentiation in tropical alpine communities. Journal of Vegetation Science 29: 835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Danet A, Kéfi S, Meneses RI, Anthelme F. 2017. Nurse species and indirect facilitation through grazing drive plant community functional traits in tropical alpine peatlands. Ecology and Evolution 7: 11265–11276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal J, Dvorsky M, Kopecky M, et al. 2019. Functionally distinct assembly of vascular plants colonizing alpine cushions suggests their vulnerability to climate change. Annals of Botany 123: 569–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falster DS, Westoby M. 2003. Plant height and evolutionary games. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18: 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Germino MJ, Smith WK, Resor AC. 2002. Conifer seedling distribution and survival in an alpine-treeline ecotone. Plant Ecology 162: 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. 1974. Vegetation classification by reference to strategies. Nature 250: 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Michalet R, Chen S, et al. 2018. Phenotypic effects of the nurse Thylacospermum caespitosum on dependent plant species along regional climate stress gradients. Oikos 127: 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kikvidze Z, Michalet R, Brooker RW, et al. 2011. Climatic drivers of plant–plant interactions and diversity in alpine communities. Alpine Botany 121: 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Gerlanc D. 2013. BootES: an R package for bootstrap confidence intervals on effect sizes. Behavior Research Methods 45: 905–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. 2011. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté E, Legendre P, Shipley B. 2014. FD: measuring functional diversity from multiple traits, and other tools for functional ecology. R package version 1.0-12.

- Lavorel S, Grigulis K, McIntyre S, et al. 2008. Assessing functional diversity in the field – methodology matters! Functional Ecology 22: 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bagousse-Pinguet Y, Gross N, Maestre FT, et al. 2017. Testing the environmental filtering concept in global drylands. Journal of Ecology 105: 1058–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmkuhl F, Klinge M, Rees-Jones J, Rhodes EJ. 2000. Late Quaternary aeolian sedimentation in central and south-eastern Tibet. Quaternary International 68–71: 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM. 1999. Indirect facilitation: evidence and predictions from a riparian community. Ecology 80: 1762–1769. [Google Scholar]

- Liancourt P, Callaway RM, Michalet R. 2005. Stress tolerance and competitive-response ability determine the outcome of biotic interactions. Ecology 86: 1611–1618. [Google Scholar]

- McIntire EJ, Fajardo A. 2014. Facilitation as a ubiquitous driver of biodiversity. New Phytologist 201: 403–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalet R, Chen SY, An ZL, et al. 2015. a Communities: are they groups of hidden interactions? Journal of Vegetation Science 26: 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Michalet R, Brooker RW, Lortie CJ, Maalouf JP, Pugnaire FI. 2015b Disentangling direct and indirect effects of a legume shrub on its understorey community. Oikos 124: 1251–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès JP, Pache G, Joud D, Magnan N, Michalet R. 2003. Direct and indirect effects of shade on four forest tree seedlings in the French Alps. Ecology 84: 2741–2750. [Google Scholar]

- Petchey OL, Gaston KJ. 2006. Functional diversity: back to basics and looking forward. Ecology Letters 9: 741–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reich PB, Walters MB, Tjoelker MG, Vanderklein D, Buschena C. 1998. Photosynthesis and respiration rates depend on leaf and root morphology and nitrogen concentration in nine boreal tree species differing in relative growth rate. Functional Ecology 12: 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Rolhauser AG, Pucheta E. 2016. Annual plant functional traits explain shrub facilitation in a desert community. Journal of Vegetation Science 27: 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld JS. 2002. Functional redundancy in ecology and conservation. Oikos 98: 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. 2012. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48: 1–36 [Google Scholar]

- Schöb C, Kammer PM, Kikvidze Z, Choler P, Von Felten S, Veit H. 2010. Counterbalancing effects of competition for resources and facilitation against grazing in alpine snowbed communities. Oikos 119: 1571–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Schöb C, Butterfield BJ, Pugnaire FI. 2012. Foundation species influence trait-based community assembly. New Phytologist 196: 824–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöb C, Armas C, Guler M, Prieto I, Pugnaire FI. 2013. Variability in functional traits mediates plant interactions along stress gradients. Journal of Ecology 101: 753–762. [Google Scholar]

- Smit C, Vandenberghe C, den Ouden J, Müller-Schärer H. 2007. Nurse plants, tree saplings and grazing pressure: changes in facilitation along a biotic environmental gradient. Oecologia 152: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliveres S, García-Palacios P, Castillo-Monroy AP, Maestre FT, Escudero A, Valladares F. 2011. Temporal dynamics of herbivory and water availability interactively modulate the outcome of a grass–shrub interaction in a semi-arid ecosystem. Oikos 120: 710–719. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D. 1982. Resource competition and community structure. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D, Lehman CL, Thomson KT. 1997. Plant diversity and ecosystem productivity: theoretical considerations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 94: 1857–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwijmeren M, Smit C, Bautista S, Wassen MJ, Rietkerk M. 2019. Combined grazing and drought stress alter the outcome of nurse: beneficiary interactions in a semi-arid ecosystem. Ecosystems 22: 1295–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Michalet R, Liu Z, et al. 2019. Stature of dependent forbs is more related to the direct and indirect above- and below-ground effects of a subalpine shrub than are foliage traits. Journal of Vegetation Science 30: 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Michalet R. 2013. Do indirect interactions always contribute to net indirect facilitation?. Ecological Modelling 268: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.