Abstract

Significance.

Deficits of disparity divergence found with objective eye movement recordings may not be apparent with standard clinical measures of negative fusional vergence (NFV) in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency.

Purpose.

To determine whether NFV is normal in untreated children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency and whether NFV improves after vergence/accommodative therapy.

Methods.

This secondary analysis of NFV measures before and after office-based vergence/accommodative therapy reports changes in: 1) objective eye movement recording responses to 4° disparity divergence step stimuli from 12 children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency compared with 10 children with normal binocular vision (NBV) and 2) clinical NFV measures in 580 children successfully treated in three Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) studies.

Results.

At baseline, the CITT cohort’s mean NFV break (14.6±4.8Δ) and recovery (10.6±4.2Δ) values were significantly greater (P <.001) than normative values. The post-therapy mean improvements for blur, break, and recovery of 5.2∆, 7.2Δ, and 1.3∆, respectively, were statistically significant (P <.0001). Mean pre-therapy responses to 4° disparity divergence step stimuli were worse in the convergence insufficiency group compared with the NBV group for peak velocity (P<.001), time to peak velocity (P=.01), and response amplitude (P<.001). Post therapy, the convergence insufficiency group showed statistically significant improvements in mean peak velocity (11.63°/sec; 95% CI: 6.6—16.62), time to peak velocity (−0.12 sec; 95% CI: −0.19 to −0.05), and response amplitude (1.47°; 95% CI: 0.83—2.11), with measures no longer statistically different from the NBV cohort (P>.05).

Conclusions.

Despite clinical NFV measurements that appear greater than normal, children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency may have deficient NFV when measured with objective eye movement recordings. Both objective and clinical measures of NFV can be improved with vergence/accommodative therapy.

The view that positive fusional vergence (i.e., convergence amplitude) is deficient in patients with convergence insufficiency is well-accepted1–3 and is supported by studies using both clinical measures4–6 and objective vergence eye movement recordings.7–10

Negative fusional vergence ability (i.e., divergence amplitude) at near, however, is often assumed to be normal or of little consequence for patients with convergence insufficiency; thus, little attention has been given to this clinical measure. Nevertheless, the standard teaching is that negative fusional vergence therapy procedures be included as a component of the therapy protocol when treating patients with convergence insufficiency.2,3,11

Most convergence insufficiency treatment studies either have not reported negative fusional vergence measures12–23 or have only reported them before treatment.4–6 The recent Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) randomized clinical trials evaluating treatments for childhood convergence insufficiency have included negative fusional vergence therapy as a component of the therapy protocol;4–6, 17 however, the change in this visual function has not been reported. We have identified only two studies reporting improvements in negative fusional vergence after treatment for convergence insufficiency.24,25 Both study cohorts had negative fusional vergence measures within the normal range before treatment with mean post-therapy improvements within one standard deviation of the normal values,26,27 rendering the results not clinically meaningful.

In an effort to expand our knowledge regarding negative fusional vergence function in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency, we analyzed data from three prior randomized trials of children treated for symptomatic convergence insufficiency.4–6 These data provided us the opportunity to determine whether the clinical measures of near negative fusional vergence are normal or deficient in children with untreated symptomatic convergence insufficiency, and also to determine whether these measures improve after vergence/accommodative therapy. In addition, using objective eye movement recordings,10 we compared disparity divergence parameters in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency versus children with normal binocular vision before and after therapy, to determine whether objective measurement techniques can identify deficiencies in dynamic fusional divergence parameters.

METHODS

The data reported and analyzed herein are previously unreported measures of negative fusional vergence/disparity divergence at near obtained pre-and post-treatment from four published studies conducted by the authors.4–6, 10 While the terms negative fusional vergence, fusional divergence, and base-in vergence are used clinically, the terms disparity vergence or disparity divergence are typically used in the objective eye movement recording literature. In this paper, we use negative fusional vergence for clinical measures of divergence and disparity divergence when referring to measures made with objective eye movement recordings.

Of these four studies, the first three were randomized clinical trials of interventions for childhood convergence insufficiency that included an office-based vergence/accommodative therapy arm and standardized clinical measures of negative fusional vergence before and after therapy.4–6 We refer to the combined data from these three studies as the Clinical Measures Dataset.

In the fourth study of children with convergence insufficiency,10 both objective eye movement recording measures of disparity divergence and clinical fusional vergence measures, were obtained before and after office-based vergence/accommodative therapy. These same measures were also collected for a control group of children with normal binocular vision who received no treatment. We refer to the data from this study10 as the Objective Measures Dataset. The clinical measures from this dataset were not combined with those from the Clinical Measures Dataset.

These studies were supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health5,6,10 and the National Science Foundation.10 The tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed, and the institutional review boards of the participating institutions approved the protocol and consent documents. Parents and participants provided written informed consent and assent, respectively, and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization was obtained prior to study participation. The studies are registered with clinialtrials.gov as NCT03248336, NCT00347945, NCT00338611, and NCT02207517. Relevant portions of the study protocols are summarized below.

Therapy Protocol Implemented

The in-office vergence/accommodative therapy protocol used in all four studies was the same except that the duration of treatment was 16 weeks for the most recent trial6 and 12 weeks for the preceding 3 studies.4, 5, 10 Details of the standardized treatment protocol have been reported previously;5 vergence treatment consisted of traditional therapy techniques such as vectograms, Brock string, aperture rule trainer, lifesaver cards, eccentric circles, loose prisms, and computerized random-dot-based vergence therapy. While the emphasis of vergence therapy was to improve the amplitude and dynamics of positive fusional vergence, negative fusional vergence was also trained using the same procedures.

Clinical Measures of Negative Fusional Vergence

The clinical measurements of negative fusional vergence at near were collected identically in all studies using the prism bar vergence method described herein. The participant, wearing his or her optical correction, viewed a hand-held fixation target consisting of a vertical line of 20/30 letters at eye level on the participant’s midsagittal plane at a distance of 40 cm, while the examiner placed the 1 prism diopter (∆) base-in increment of a horizontal prism bar before one eye and then slowly (approximately 2∆/second) introduced increasing magnitudes of base-in prism (2∆ increments from 2∆ to 20∆, and 5∆ increments from 20∆ to 45∆). The participant was instructed to report when the letters became blurry or doubled, but to try to keep the letters single and clear for as long as possible. The examiner paused at each prism increment to confirm that the letters were “single and clear” and noted the prism magnitudes where the endpoints of blur and diplopia were reported. After diplopia was reported, the prism magnitude was increased by 5∆, and then slowly reduced in magnitude until single vision was reported; the prism magnitude for this endpoint was the “recovery” finding.

Clinical Measures Dataset

This dataset consists of the blur, break, and recovery values for negative fusional vergence at near that were measured by certified masked examiners using the aforementioned prism bar method pre- and post-therapy for the participants in the three CITT trials who were randomized to office-based vergence/accommodative therapy and had a successful outcome using the CITT composite convergence criterion.4–6 This success criterion requires that participants attain both a normal near point of convergence (<6 cm) and normal positive fusional vergence (passing Sheard’s criteria28 and a break finding >15Δ) at the end of the trial.

Objective Measures Dataset

Objective Measures of Disparity Divergence

An overview of the instrumentation (Figure 1), presentation of stimuli, and parameters evaluated for the objective vergence eye movement recordings are described herein, with complete details provided elsewhere.10 The infrared pupil/corneal reflection binocular eye tracker system, ISCAN RK-826PCI (Woburn, MA, USA), was used to objectively record horizontal vergence eye movements. This system is situated within a traditional haploscope configuration and uses an infrared emitter and two infrared cameras to objectively measure the centroid of the pupil to capture eye movement data at 240 frames per second. The presentation of visual stimuli for the left and right eye stimuli displays was synchronized with the objective eye movement response data acquisition using custom software.8, 10, 29 Calibration was conducted monocularly for each participant prior to data collection over the range of visual stimuli to be presented. The specific vergence positions for calibration were 12°, 10°, 8°, 6°, 4° and 2° to encompass the vergence eye movement response range.

Figure 1.

Haploscope instrument used to collect objective eye movement recordings.

Six different 4° and 6° symmetrical, step stimuli for convergence and for divergence were presented in pseudo random order (i.e., participant could not predict the order of stimulus presentation, but the sequence was fixed within the computer script so that an equal number of 4° and 6° step stimuli visual stimuli were presented). This mode of presentation reduces anticipatory cues known to influence temporal and dynamic properties of vergence eye movements.30–32 The target was a vertically oriented difference of Gaussians. The participant was instructed that when they experienced double vision, they were to try and regain single vision as quickly as possible. The presentation sequence was repeated 12 times, yielding a total of 144 intermixed divergence and convergence symmetrical step stimuli. Of the 144 divergence and convergence presentations, 96 were step stimuli of 4° and 48 were step stimuli of 6°. There were more 4° than 6° stimuli because responses to the larger 6° stimuli are more difficult to initiate. It was important to have stimuli of different magnitudes and direction to reduce the participant’s ability to predict the next stimulus and hence reduce anticipatory cues. However, we also wanted to optimize time, since many participants are unable to respond to 6° stimuli. The visual stimuli were presented at different initial vergence angles within the range of 2° to 12°. The initial vergence angles for the 4° symmetrical step stimuli to assess disparity divergence were 12°, 10°, 8° and 6° (4 stimuli defined by different initial vergence angles). The 6° symmetrical disparity divergence step stimuli began at 12° and 8° (2 stimuli defined by different initial vergence angles). Hence, there were 6 types of disparity divergence step responses recorded. Testing required approximately 20–25 minutes, and participants were provided opportunities to rest if needed. Only the disparity divergence data are presented in this report; the disparity convergence data have been reported elsewhere.10

Four objective disparity divergence parameters were analyzed (Figure 2): peak velocity (°/sec), time to peak velocity (sec), latency (sec), and response amplitude (°). Peak velocity is the highest velocity attained during the transient portion of the vergence movement. Time to peak velocity is the time from introduction of the stimulus target to the time that vergence reaches its peak velocity within the transient portion of the response. Latency is the time from the introduction of the stimulus target to the time when the average positional amplitude deviates 5% from the stimulus amplitude. The response amplitude is the magnitude of the final response in degrees.

Figure 2.

Vergence demand (plotted as angular position in degrees) as a function of time (seconds) is depicted by the blue trace, with the latency (orange arrow) and response amplitude (blue bracket) indicated. Vergence velocity (degrees/sec) plotted as a function of time is indicated by the green trace with the peak velocity (green arrow) indicated.

Masking

Examiners measuring negative fusional vergence were masked to treatment group assignment for the three randomized trials that comprise the clinical measures dataset. For the objective measures study, those who collected the data were not masked, but those who analyzed these data were masked to treatment group assignment.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance, and 95% confidence intervals (CI’s) were calculated for within- and between-group differences for the 4 objective vergence eye movement recording outcome measures and for the clinical measures of blur, break, and recovery. Statistical tests were performed on both small (<15) and large (>100) samples. For large sample tests, t tests were used. For differences involving small samples, non-parametric statistical tests were performed. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine if the median change in objective disparity divergence measures from pre- to post-vergence/accommodative therapy was significant, and the corresponding 95% CI was calculated using the bootstrap method.33 The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to determine if the median objective disparity divergence parameter in the group of participants with convergence insufficiency differed from the normal binocular vision group median, both before and after the participants with convergence insufficiency underwent treatment. The corresponding 95% CI was estimated using the Hodges-Lehmann method.34 To determine if the changes in objective measures were clinically meaningful, effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d, which was computed using the standard deviation (SD) estimates from a previous study of 118 children with normal binocular vision.35 For Cohen’s d, an effect size between 0.2 to 0.49 is considered small, between 0.5 to 0.79 is medium, and 0.8 or greater is large.36 If pre- and post- means do not differ by 0.2 or more standard deviations, the difference is considered clinically trivial, even if statistically significant.

For the pooled clinical measures dataset, we compared the mean fusional divergence break and recovery measures with normal values for prism bar vergence testing in children from a prior study.27 (We were unable to perform comparisons for blur measures because clinical norms are not available). The mean within-group change in negative fusional vergence after vergence/accommodative therapy was determined and we considered a change greater than one standard deviation (SD) from the mean to be clinically meaningful.

RESULTS

Clinical Measures Dataset

Of the 580 participants enrolled in the three randomized clinical trials, 201 were assigned to office-based vergence/accommodative therapy and met the CITT composite convergence outcome of success of attaining both a normal near point of convergence and normal near positive fusional vergence measures.5 For these 201 participants, the mean (SD) age was 11.1 (1.9) years and 122 (61%) were female.

The mean pre-therapy measurements for negative fusional vergence break and recovery findings for all 580 participants with convergence insufficiency and the post-therapy results for the 201 who met the CITT composite convergence success criterion are shown in Table 1. The mean (SD) baseline negative fusional vergence break of 14.6Δ (4.8Δ) and recovery of 10.6Δ (4.2Δ) found in our clinical measures cohort is significantly greater than the published normative values of 11.0Δ (3.0Δ) and 7.0Δ (3.0Δ), respectively (P <.0001 for both).27 In addition, both the mean break and recovery values are greater than 1 standard deviation from the mean, suggesting a clinically significant difference.

Table 1.

Disparity divergence parameters before and after office-based vergence/accommodative therapy for 4° symmetrical disparity divergence step stimuli

| Disparity Divergence Parameter* | Convergence Insufficiency Group vs. Normal Binocular Vision Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | Post-treatment | |||

| Median Difference (95% CI) |

P-gvalue | Median Difference (95% CI) |

P-value | |

| Peak Velocity (°/sec) | 9.08 (3.94, 13.78) | .0004 | −1.49 (−9.01, 4.72) | .41 |

| Time to Peak Velocity (sec) | −0.12 (−0.22, −0.03) | .01 | 0 (−0.05, 0.06) | .96 |

| Response Amplitude (°) | 1.45 (0.96, 1.96) | <.0001 | 0.08 (−0.36, 0.66) | .87 |

| Latency (sec) | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.05) | .57 | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.05) | .29 |

Measured by objective eye movement recordings; CI = confidence interval; ° = degrees; sec = seconds; °/sec=degrees per second; P values are for Wilcoxon rank-sum tests of the hypotheses of no mean group differences. The median differences and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are Hodges-Lehmann estimates.33

A statistically significant improvement occurred for all three components of negative fusional vergence after vergence/accommodative therapy, with mean improvements of 5.2∆ (95% CI: 4.5—6.0), 7.2Δ (95% CI: 6.2—8.2), and 1.3∆ (95% CI: 0.8—1.8) for blur, break, and recovery, respectively (all Ps <.0001). Because the mean improvement in the break measurement is greater than one standard deviation, this change is also clinically meaningful.

Objective Measures Dataset

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

Twenty-two children (age range of 12 to 17 years of age) were recruited from the Eye Institute of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University; 12 had symptomatic convergence insufficiency and 10 had normal binocular vision. The mean (SD) age at enrollment for the participants with convergence insufficiency was 13.1 (2.5) years and 14.2 (2.1) years in the normal binocular vision group.

Clinical Measures Pre- and Post-Vision Therapy

At baseline, the mean (SD) negative fusional vergence measures for break and recovery were 14.8Δ (6.5∆) and 10.2Δ (5.7∆), respectively, in the 12 participants with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. These findings were not statistically different from the measures for the participants in the clinical measures dataset. After treatment, the mean (SD) negative fusional vergence measures for break and recovery were 19.6Δ (6.1∆) and 15.4Δ (4.9∆), respectively.

Objective Eye Movement Recordings of Disparity Divergence Parameters: Pre- and Post-Treatment Measures for Participants with Convergence Insufficiency Compared with Untreated Participants with Normal Binocular Vision

Of the 12 participants with convergence insufficiency, 8 (67%) either could not fuse the 6° step stimuli or had excessive blinking or saccades during the transient portion of this vergence eye movement which prevented a meaningful analysis from being conducted for this stimuli. Thus, we only report the results for the 4° disparity divergence step stimuli.

Prior to treatment, statistically significant median group differences were present between the convergence insufficiency and normal binocular vision groups for peak velocity, time to peak velocity, and response amplitude for the 4° disparity divergence step stimuli. Latency was not significantly different between the groups (Table 2, Figures 3a to 3d). After the convergence insufficiency group completed vergence/accommodative therapy, no statistically significant differences (P>.05) were found between the two groups for any of the four fusional divergence parameters (Table 2, Figures 3a to 3d).

Table 2.

Mean Near Negative Fusional Vergence Measures (Prism Bar Method) for Children with Symptomatic CI: Normative Data36 Compared with Untreated Symptomatic CI and Clinical Cohort Post-Treatment.

| Negative Fusional Vergence | Normative Data† Mean (SD) |

Untreated Symptomatic CI* |

CI-Clinical Cohort Post-Treatment‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | ||

| Break (∆) | 11 (3) | 578 | 14.6 (4.8) | 199 | 22.1 (6.5) |

| Recovery (∆) | 7 (3) | 580 | 10.6 (4.2) | 200 | 12.3 (4.5) |

(∆)=prism diopters; SD=standard deviation; CI=convergence insufficiency

Normative data;

All participants from 3 CITT randomized clinical trials.

Present study clinical cohort who underwent vergence/accommodative therapy.

Figure 3.

Distributions of values from the objective measures dataset are summarized in separate boxplots for the participants with normal binocular vision (NBV), the convergence insufficiency participants at baseline (CI - Pre), and the convergence insufficiency participants after office-based vergence/accommodative therapy (CI - Post). (A) displays the data for peak velocity (°/sec), (B) for time to peak velocity (sec), (C) for response amplitude (°), and (D) for latency (sec). In these boxplots, the bottom and top of the box are the first and third quartiles, and the horizontal line within the box is the median. The ‘+’ indicates the mean. Whiskers are drawn to the most extreme data points within the upper or lower edge of the box plus 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). Responses outside the range of the whiskers are identified with stars.

Post-therapy, the convergence insufficiency group showed statistically significant improvements for the three disparity divergence parameters that were reduced at baseline. Median changes were 11.13°/sec (95% CI: 5.9—16.44 °/sec; P=.0005) for peak velocity, −0.11 sec (95% CI: −0.22 to −0.06 sec, P=.004) for time to peak velocity, and 1.52° (95% CI: 0.77—1.83°, P =.001) for response amplitude. The calculated effect sizes were 3.88 for peak velocity, 0.93 for time to peak velocity, and 2.45 for response amplitude. These effect sizes all exceed Cohen’s convention for a large (≥0.80) effect, suggesting a high level of clinical significance. The median change in latency was not statistically significant (P >.05).

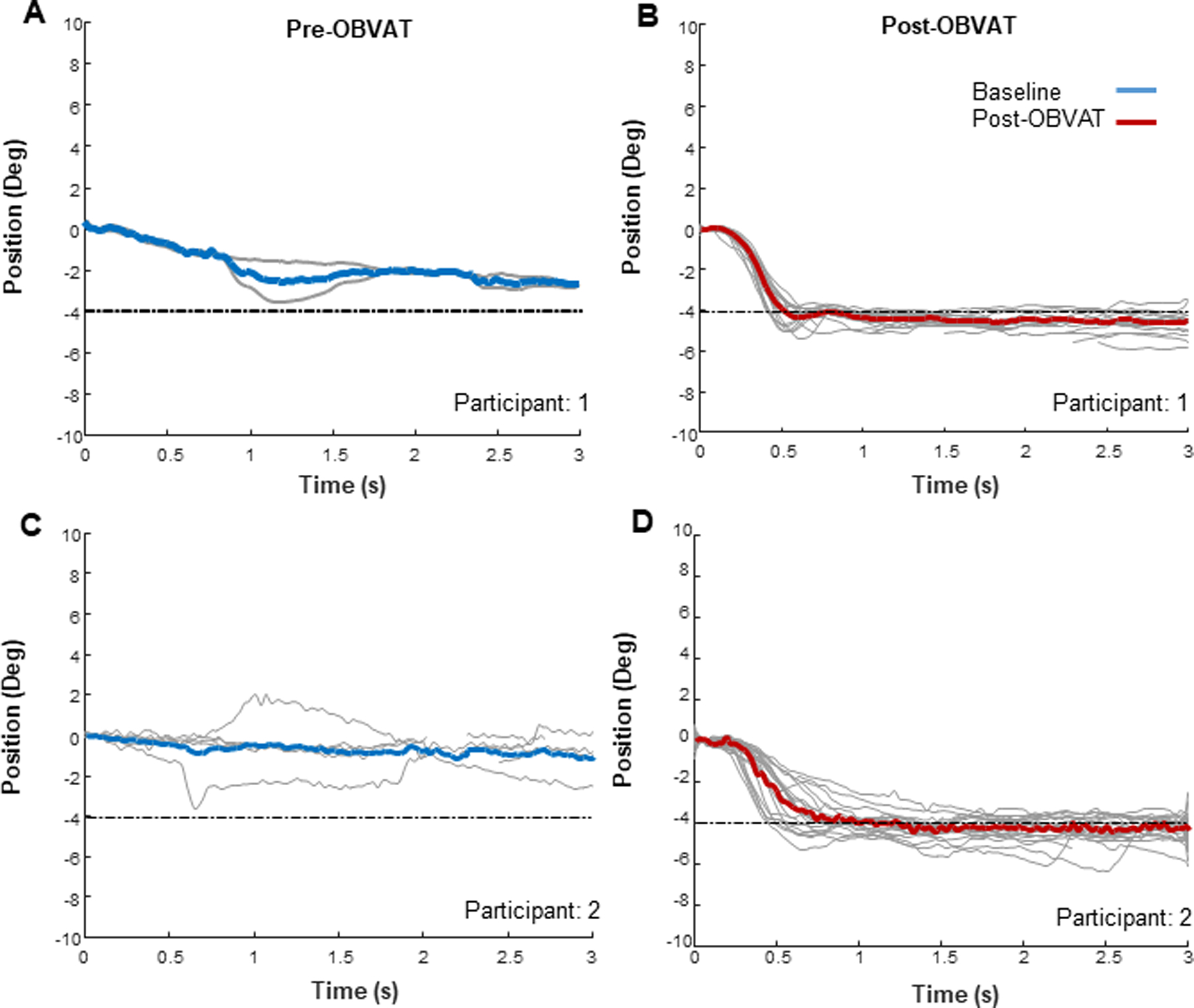

Figure 4 is an ensemble plot of multiple disparity divergence eye movements in response to symmetrical 4° disparity divergence step stimuli from a participant with normal binocular vision. This example of multiple divergence responses shows response amplitudes that are minimally different and closely match the stimulus amplitude. The solid red line is the averaged response.

Figure 4.

Ensemble of individual disparity divergence eye movements (grey traces) in degrees as a function of time (seconds) for a control participant with normal binocular vision. The average of the divergence responses is shown in red. Deg=degrees; S = seconds.

In contrast, 8 of 12 (66.7%) participants with convergence insufficiency had impaired disparity divergence responses before treatment. Figure 5 is an ensemble plot for two participants showing significant differences in their responses to the 4° disparity divergence step stimuli after completing vergence/accommodative therapy. Substantial impairment in disparity divergence is evident before treatment (5A and 5C), with Participant 1 demonstrating a poor response amplitude to the 4° disparity divergence step stimulus (5A). After treatment, Participant 1’s response amplitude is more accurate for the same stimulus (5B). Pre-therapy, Participant 2 was only able to generate a few disparity divergence responses from 72 presentations of the 4° disparity divergence step stimulus (5C). However, post-therapy (5D), this same participant executed many more disparity divergence responses, with a response amplitude that closely matched the 4° stimulus. The average of the responses generated pre- and post-therapy are plotted as the solid blue and solid red lines, respectively. Individual data points that were blinks have been omitted.

Figure 5.

Ensemble disparity divergence responses from Participant 1 before (A) and after (B) office-based vergence/accommodative therapy, and from Participant 2 before (C) and after (D) office-based vergence/accommodative therapy. Each gray trace is a single disparity divergence response. The blue trace and the red traces are the mean responses before and after therapy, respectively. Deg=degrees, s = seconds, OBVAT = office-based vergence accommodative therapy.

DISCUSSION

In a large cohort of school-age children with untreated symptomatic convergence insufficiency from three randomized trials, the mean negative fusional vergence measures at near were significantly greater than published norms. The same was true for the 12 children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency enrolled into the objective measures study; their mean negative fusional vergence amplitudes were nearly identical to the larger cohort (i.e., break/ recovery of 14.8∆/10.2∆ versus 14.6∆/10.6∆, respectively). In contrast, the median divergence parameters for peak velocity, time to peak velocity, and response amplitude measured by objective eye movement recordings for these 12 participants were significantly worse compared with normal controls, with two-thirds showing impaired disparity divergence responses before treatment. After treatment, not only did their clinical measures of negative fusional vergence improve, but these three disparity divergence parameters improved significantly and were no longer statistically different from the normal control group’s measures. Similarly, in the large clinical trial cohort, the mean clinical negative fusional vergence break measure showed a statistically significant improvement after therapy.

One might interpret these findings, improvements in clinical measures of negative fusional vergence and normalization of objective dynamic disparity divergence parameters, as providing support for the common clinical teaching that negative fusional vergence procedures should be incorporated into the vergence/accommodative therapy regimen for children with convergence insufficiency.2, 3, 11, 37 In fact, some have suggested that solely training positive fusional vergence may result in convergence excess (near esophoria or eso-fixation disparity with reduced negative fusional vergence) post therapy.3, 37, 38 We are not aware of any studies that have tested the veracity of this clinical impression. Furthermore, because both divergence and convergence therapy procedures were performed in all four studies, divergence therapy’s contribution to the successful outcomes for our participants is uncertain. We have not found any studies that have compared a therapy regimen of solely positive fusional vergence procedures with one comprised of both positive and negative fusional vergence procedures. Determining whether negative fusional therapy is integral to the successful treatment of symptomatic childhood convergence insufficiency using vergence/accommodative therapy and whether the absence of divergence therapy results in post-therapy esodeviations are worthy of further study.

Presumably, it is the targeted divergence therapy that leads to the clinically meaningful improvement found in the negative fusional vergence amplitude. In the few reports of increased negative fusional vergence after vision therapy for childhood convergence insufficiency,24,25,39 improvements were small and not clinically meaningful. Our clinical outcomes cohort demonstrated statistically significant improvements for all three negative fusional vergence endpoints (blur, break, recovery), with the most commonly measured break endpoint also being clinically significant. To our knowledge, our study is the first to document both a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in the negative fusional vergence break endpoint after vergence/accommodative therapy for children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. The relationship of this improvement in divergence ability to improved visual comfort or function in these children is unknown.

It was somewhat surprising to find that children with untreated symptomatic convergence insufficiency had clinical measures of negative fusional vergence that were significantly greater than the established norms. However, the children in our clinical convergence insufficiency cohort had a mean near exophoria of 9.9∆, compared with the of 0.4 exophoria of the normative comparison group.27 When base-in prism is introduced for an individual with exophoria, the prism initially reduces the convergence demand, rather than stimulating active divergence, and it is not until the base-in prism fully offsets the exodeviation that active negative fusional vergence is necessary to sustain fusion. Thus, the actual divergence amplitude is determined by subtracting the exodeviation magnitude from the measured negative fusional vergence blur (or diplopia if no blur) endpoint. In the present clinical study, subtracting the mean (9.8∆ exophoria) from the mean negative fusional vergence break of 14.6∆ results in an negative fusional vergence value that is less than the normative measure of 11∆.

In the objective-measures cohort, the objective eye movement recording assessments revealed anomalies of disparity divergence that were not evident based on the clinical measures of negative fusional vergence. The nature of these measurements may explain this incongruence. The clinical measurement of negative fusional vergence is a one-time, static measure of divergence amplitude, whereas the objective eye movement recordings also assess the latency and velocity of the vergence response, and the final data point is a compilation of 72 measurements. The role of fatigue with repeated measurements is unknown.

The clinical studies from which the data for these analyses were derived had a number of strengths including randomization, standardized measurements and treatment protocol, post-treatment negative fusional vergence assessments by masked examiners, a large sample size, and well-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. The primary strength of the objective measures study was the use of objective vergence eye movement recordings to document the different parameters of disparity divergence before and after treatment. In addition, the inclusion/exclusion criteria, clinical measures, and treatment protocol were identical to those implemented in the three clinical studies, and the analyses of the eye movement recordings were performed by a person masked to treatment group. We recognize that there are also limitations to our study. The lack of available normative values for the blur endpoint using the prism bar method to measure negative fusional vergence prevented us from determining the adequacy of this endpoint. The sample size for the objective eye movement recordings was modest; recordings from larger samples of normal children and children with convergence insufficiency would be beneficial. Furthermore, our study design does not allow us to determine to what extent the divergence therapy techniques contributed to the improvements found in the clinical and objective measures of divergence and to the successful treatment of convergence insufficiency. The study was also unable to address the relationship between improved divergence ability and better visual comfort or function in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that, on average, children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency have greater than normal clinical measures of near negative fusional vergence (when the magnitude of the phoria is not considered), despite exhibiting deficient disparity divergence as documented by objective measures of vergence eye movements. Both the clinical and the objective measures of disparity divergence improved after in-office vergence/accommodative therapy. Future studies investigating the treatment of convergence insufficiency or other binocular vision disorders should, when possible, include objective eye movement recordings of vergence to capture vergence deficiencies that might not be evident with standard clinical measures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by National Eye Institute grants U10 EY014713-01A2 and U10 EY014713-01A2 to MS, and NSF MRI CBET 1428425 to TLA and NIH 1R01EY023261 to TLA.

Footnotes

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trials (CITT) – Clinical Sites & Investigators

The clinical sites that participated in the CITT studies described in this paper are listed below. The investigators for each study can be found in the following publications:

Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments for Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:14–24.

CITT Study Group. Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments for Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1336–49.

CITT-ART Investigator Group. Treatment of Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children Enrolled in the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention & Reading Trial: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Optom Vis Sci 2019;96:825–35.

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial: Pilot Study 2003–2005

Pennsylvania College of Optometry, Southern California College of Optometry, State University of New York College of Optometry, The Ohio State University College of Optometry, Pacific University College of Optometry

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial 2004–2008

Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, State University of New York College of Optometry, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Optometry, NOVA Southeastern University College of Optometry, Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University, The Ohio State University College of Optometry, Southern California College of Optometry, University of California–San Diego Ratner Children’s Eye Center, Mayo Clinic Department of Ophthalmology (Rochester, MN)

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial: Attention and Reading Trial 2015–2019

State University of New York College of Optometry, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University, The Ohio State University College of Optometry, Southern California College of Optometry at Marshall B Ketchum University, Akron Children’s Hospital, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Optometry, NOVA Southeastern University College of Optometry, Advanced Vision Center, Schaumburg, IL

Contributor Information

Mitchell Scheiman, Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania.

Tara L. Alvarez, Department of Biomedical Engineering, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey.

Susan A. Cotter, Southern California College of Optometry at Marshall B. Ketchum University, Fullerton, California.

Marjean T. Kulp, The Ohio State University College of Optometry, Columbus, Ohio.

Loraine T. Sinnott, The Ohio State University College of Optometry, Columbus, Ohio.

Maureen D. Plaumann, The Ohio State University College of Optometry, Columbus, Ohio.

Jasleen Jhajj, Nova Southeastern University, College of Optometry, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida.

REFERENCES

- 1.von Noorden G Burian-Von Noorden’s Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility: Theory and Management of Strabismus, 6th ed. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin JR, Grisham JD, Borsting EJ. Binocular Anomalies: Theory, Testing and Therapy, 4th ed. Santa Ana, CA: Optometric Extension Program Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters-Kluwer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. A Randomized Trial of the Effectiveness of Treatments for Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments for Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1336–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CITT-ART Investigator Group. Treatment of Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children Enrolled in the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial–Attention & Reading Trial: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Optom Vis Sci 2019;96:825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarez TL, Vicci VR, Alkan Y, et al. Vision Therapy in Adults with Convergence Insufficiency: Clinical and Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measures. Optom Vis Sci 2010;87:985–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheiman MM, Talasan H, Mitchell GL, Alvarez TL. Objective Assessment of Vergence after Treatment of Concussion-Related CI: A Pilot Study. Optom Vis Sci 2017;94:74–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheiman M, Ciuffreda KJ, Thiagarajan P, et al. Objective Assessment of Vergence and Accommodation after Vision Therapy for Convergence Insufficiency in a Child: A Case Report. Optom Vis Perf 2014;2:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheiman M, Talasan H, Alvarez TL. Objective Assessment of Disparity Vergence after Treatment of Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Optom Vis Sci 2019;96:3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press LJ. Applied Concepts in Vision Therapy. Santa Ana, CA: Optometric Extension Program Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birnbaum MH, Soden R, Cohen AH. Efficacy of Vision Therapy for Convergence Insufficiency in an Adult Male Population. J Am Optom Assoc 1999;70:225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adler P Efficacy of Treatment for Convergence Insufficiency Using Vision Therapy. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2002;22:565–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen AH, Soden R. Effectiveness of Visual Therapy for Convergence Insufficiencies for an Adult Population. J Am Optom Assoc 1984;55:491–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serna A, Rogers DL, McGregor M, et al. Treatment of Convergence Insufficiency with a Home-Based Computer Orthoptic Exercise Program. JAAPOS 2011;15:140–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KM, Chun BY. Effectiveness of Home-Based Pencil Push-Ups (HBPP) for Patients with Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency. Korean J Ophthalmol 2011;25:185–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheiman MM, Hoover DL, Lazar EL, et al. Home-Based Therapy for Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93:1457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teitelbaum B, Pang Y, Krall J. Effectiveness of Base in Prism for Presbyopes with Convergence Insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci 2009;86:153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallaway M, Scheiman M, Malhotra K. The Effectiveness of Pencil Pushups Treatment for Convergence Insufficiency: A Pilot Study. Optom Vis Sci 2002;79:265–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin HS, Park SC, Maples WC. Effectiveness of Vision Therapy for Convergence Dysfunctions and Long-Term Stability after Vision Therapy. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2011;31:180–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momeni-Moghaddam H, Kundart J, Azimi A, Hassanyani F. The Effectiveness of Home-Based Pencil Push-up Therapy Versus Office-Based Therapy for the Treatment of Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Young Adults. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2015;22:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheiman M, Cotter S, Rouse M, et al. Randomised Clinical Trial of the Effectiveness of Base-in Prism Reading Glasses Versus Placebo Reading Glasses for Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:1318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Vision Therapy/Orthoptics Versus Pencil Pushups for the Treatment of Convergence Insufficiency in Young Adults. Optom Vis Sci 2005;82:583–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daum KM. Convergence Insufficiency. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1984;61:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang JU, Jang JY, Tai-Hyung K, Moon HW. Effectiveness of Vision Therapy in School Children with Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2017;12:187–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheiman M, Herzberg H, Frantz K, Margolies M. A Normative Study of Step Vergence in Elementary Schoolchildren. J Am Optom Assoc 1989;60:276–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez R, Perez MA, Garcia JA, Gonzalez MD. Statistical Normal Values of Visual Parameters That Characterize Binocular Function in Children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2004;24:528–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheard C Zones of Ocular Comfort. Am J Optom 1930;7:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Y, Kim EH, Alvarez TL. Visualeyes: A Modular Software System for Oculomotor Experimentation. JoVE 2011;49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alvarez TL, Bhavsar M, Semmlow JL, et al. Short-Term Predictive Changes in the Dynamics of Disparity Vergence Eye Movements. J Vis 2005;5:640–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarez TL, Alkan Y, Gohel S, et al. Functional Anatomy of Predictive Vergence and Saccade Eye Movements in Humans: A Functional MRI Investigation. Vision Res 2010;50:2163–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar AN, Han Y, Garbutt S, Leigh RJ. Properties of Anticipatory Vergence Responses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002;43:2626–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodges JL Jr, Lehmann EL. Hodges-Lehmann Estimators, Vol. 3 In: Kotz S, Johnson NL, Read CB, eds. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1983:463–5. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Namaeh M, Scheiman M, Yaramothu C, Alvarez TL. A Normative Study of Objective Measures of Disparity Vergence and Saccades in Children 9 to 17 Years Old. Optom Vis Sci 2020;97:416–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NH: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frantz KA. Understanding Convergence Insufficiency. Optom Management 1994:50–5.

- 38.Birnbaum MH. Optometric Management of Nearpoint Vision Disorders. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper J, Selenow A, Ciuffreda KJ, et al. Reduction of Asthenopia in Patients with Convergence Insufficiency after Fusional Vergence Training. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1983;60:982–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]