Abstract

Background

High out-of-pocket health expenditure is a common problem in developing countries. The employed population, rather than the general population, can be considered the main contributor to healthcare financing in many developing countries. We investigated the feasibility of a parallel private health insurance package for the working population in Ulaanbaatar as a means toward universal health coverage in Mongolia.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used a purposive sampling method to collect primary data from workers in public and primary sectors in Ulaanbaatar. Willingness to pay (WTP) was evaluated using a contingent valuation method and a double-bounded dichotomous choice elicitation questionnaire. A final sample of 1657 workers was analyzed. Perceptions of current social health insurance were evaluated. To analyze WTP, we performed a 2-part model and computed the full marginal effects using both intensive and extensive margins. Disparities in WTP stratified by industry and gender were analyzed.

Results

Only < 40% of the participants were satisfied with the current mandatory social health insurance in Mongolia. Low quality of service was a major source of dissatisfaction. The predicted WTP for the parallel private health insurance for men and women was Mongolian Tugrik (₮)16,369 (p < 0.001) and ₮16,661 (p < 0.001), respectively, accounting for approximately 2.4% of the median or 1.7% of the average salary in the country. The highest predicted WTP was found for workers from the education industry (₮22,675, SE = 3346). Income and past or current medical expenditures were significantly associated with WTP.

Conclusion

To reduce out-of-pocket health expenditure among the working population in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, supplementary parallel health insurance is feasible given the predicted WTP. However, given high variations among different industries and sectors, different incentives may be required for participation.

Keywords: Social health insurance, Private health insurance, Willingness-to-pay, Contingent valuation, Universal coverage

Background

The achievement of universal health care (UHC) coverage, which is one of United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) [1] to reverse the impoverishing effects of out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditures, is a challenge faced by many developing countries, including Mongolia.

Mongolia introduced social health insurance (SHI) in 1994 to achieve UHC; it is compulsory for all public and private sector employees and voluntary for unemployed people. The type of contribution is income-based and is equal to 4% of the insurant’s monthly salary, which is equally shared between the employer and employee [2]. The SHI package, however, covers only limited inpatient and outpatient services in public and some contracted private health care providers [3]. The coverage provided by the Mongolian SHI is highly inadequate. In Mongolia, OOP expenditure accounted for 41% of the total health expenditure in 2011, causing a severe household financial burden [2].

Moreover, the Mongolian population relies heavily on private health care providers because of service delivery failures in the public sector, including complicated hospital admission practices, poor referral and appointment system, and long waiting times [4]. This high level of dissatisfaction with public health care services is common in developing countries [5]. Private health care providers are often perceived to offer better services, technology, and ease of access [6, 7]. A high utilization rate of private health care services exists among workers. However, these services are not fully covered by the existing SHI system in Mongolia, which can result in considerable and often unpredictable health care OOP expenditure [2, 8–10].

Studies on the use of private health insurance (PHI) as a means to achieve UHC are limited. Most previous studies have focused on the use of national or public health insurance programs as a means of achieving UHC [11]. However, PHI could play a positive role in improving health financing when it complements the existing SHI, especially when the SHI provides only limited coverage [12, 13].

In this study, we assessed the demand of PHI among workers from different industries in Mongolia by analyzing their willingness to pay (WTP) for PHI. Most of the previous studies investigating WTP for PHI have often focused on the general population. In the case of Mongolia, focusing on employees, instead of the general population, is a more feasible approach for several reasons. First, Mongolia has a very high proportion (65%) of working-age population (i.e., female and male citizens aged 15 to 55 or 60 years, respectively), which can be viewed as an enormous demographic window according to the 2018 National Statistical Office (NSO) Report [14]. Therefore, relying on the employed population to finance health care expenditure is considered more feasible. Notably, the employed population contributes the most to healthcare financing in several countries [13].

Second, Mongolia has successfully transitioned into a market-oriented economy since 1990. During the transition period, the employment rate decreased sharply from 87 to 62% until 2001 [15]. After the transition, the Mongolian economy started heavily exploiting its mineral deposits [16], shifting away from its previous considerable dependence on the agriculture sector, in which the employment rate was 40.3% in 2007 and decreased to 27.8% in 2014 [17]. These shifts exacerbated the existing disparities among workers from all industries. The traditional labor market is concentrated in the mining sector. Therefore, examining the WTP of employees from the different sectors is essential for determining the feasibility of the parallel health insurance system. Without sufficient insights into the WTP of employees from various industries (rather than the general population), establishing a well-functioning UHC/SHI system will be challenging. This may not be the case for countries where the government implements universal health insurance with mandatory enrollment, regardless of employment [18].

Third, Mongolia’s labor market is characterized by high mobility. High mobility and low tenure in the labor market can be addressed by the parallel PHI system, as it can be provided as a job incentive and can effectively attract talent from the labor market [19].

Our study assessed the Mongolian population’s current satisfaction levels with the mandatory SHI and analyzed the WTP for private parallel insurance across industries. This was an exploratory study of the working population in Mongolia. Considering the high gender employment inequality prevalent in Mongolia [15, 20, 21], we also tested any gender gaps in our estimates to highlight the gender disparities among employees in Mongolia.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional survey between July and September 2018 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. We used purposive sampling to collect data from 22 public and private companies from 11 industries in Ulaanbaatar: mining, processing, electricity, construction, wholesale and retail, transportation, information and communication, finance and insurance, public administration, education, and health care. A total of 83.3% of all employees in Ulaanbaatar work in these 11 industries, representing both the public and private sectors [22]. We aimed to involve the organizations that represent Mongolian industries based on their market share based on the advice of the Mongolian National Chamber of Commerce and Industry. The content validity of the questionnaire was examined by public health experts, statistical specialists, and professors from National Yang-Ming University (Taiwan) and Ach Medical University (Mongolia). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Yang-Ming University (YM107064E-2), Taipei, Taiwan, and by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ach Medical University (12/23), Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

The working population in Ulaanbaatar in 2018 was estimated by the NSO to be 555,350 people, with 303,544 men and 251,806 women. The sample size n for our study was determined using Slovin’s formula for a known population [23, 24]:

where N is the population size (555350), and e is the level of precision (set as 0.05). Considering the response rate and missing data, we assigned a higher number, and 1925 full-time employees from 11 industries, 18 private companies, and 4 public administrations agreed and accepted our invitation letters to participate in the study and completed the questionnaire (overall response rate = 86.1%). After excluding 268 individuals with missing data, we included 1657 participants.

Perception of the current social health insurance system

To determine the WTP questions for private health insurance, first, we obtained the participants’ perception of the current mandatory social health insurance system by using the following questions:

Are you satisfied with social health insurance? (Yes/No);

Please tick one best thing you like about social health insurance (premium/quality/level of convenience/other);

Please tick one worst thing you dislike about social health insurance (premium/quality/level of convenience/other);

What would you like to improve in the social health insurance system if you had a chance to do so? (service/quality/health care provider/premium/other)

WTP for parallel private health insurance

We used the contingent valuation (CV) method to examine the preferences of individuals to determine WTP [25, 26]. We used a double-bounded dichotomous choice elicitation questionnaire, as used in studies to determine WTP for private health insurance in low- and middle-income countries [25, 27].

Hypothetical private health insurance package

We proposed the following private health insurance package with total coverage of 5 times higher (Mongolian Tugrik [MNT or ₮] 10,000,000 or US$4167) than the present annual coverage by social health insurance. This amount was set after discussion with public health experts and health economists in Mongolia, who believe such an amount is required for reasonable financial protection. In the proposed package (explained below), the coverage would include the cost of health services and drugs not covered by SHI. We set the starting premium at ₮30,000 to exemplify future similar insurance products. The premium amount was equal to 5% of the median salary (₮670,300 in 2017 according to the NSO), which is a reasonable percentage based on Asian countries that have achieved UHC successfully [28]. The proposed package was laid out in the following manner:

How much would you pay for private medical insurance if such a product were available? Here, we assume that such private medical insurance will reimburse you up to ₮10,000,000 for hospitalization and other medical costs (e.g., outpatient, inpatient, drug costs, laboratory test) not covered by the current social health insurance. This amount can be used on yourself only and not transferable to your family members, who will each have to use a separate policy. Please look at the price of the premium below and tell us whether you will be willing to pay that amount of premium per month (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Willingness to pay flow diagram

Feasibility assessment

Our proposed package is aimed to be provided by private health insurance companies. Thus, the product must be profitable so that private companies would be willing to offer the product. After consultations with private insurance companies’ health insurance specialists, the premium and benefit package we offered was more competitive than the existing private insurance products in Mongolia. The offered package was thus deemed profitable after actuarial calculation.

Studies using a CV survey indicated that WTP that the respondents state on behalf of their households is not significantly different from their individual WTP [29]. However, it may vary depending on household and respondent’s characteristics, but the main factor is a clear description of the good in the WTP question [30]. The current social health insurance premium is set on an individual basis and not on a household basis, as in other countries [29, 31, 32]. We specifically made the package nontransferable to family members, as the objective of this package is to improve the health of the working population instead of the general population.

Similar to other studies on WTP for developing countries [25, 26], we set the initial premium as ₮30,000 (1 USD ≈ ₮2400 in 2018, which means approximately US$12 per month) and then subtracted and added ₮10,000 to the initial bid to estimate WTP.

Other covariates

We chose relevant covariates by using a model-building process. First, we selected relevant covariates from the literature and retained those with P < .2 as potential candidate covariates. As we wished to test gender differences, each covariate was interacted with the gender variable. We then discarded variables that were not statistically significant in any of the models (bivariate and 2-part model, explained later). However, we retained self-rated health despite its nonsignificance in any model because of its strong theoretical significance in the literature for the demand for health insurance [25, 27]. Covariates analyzed in this study included education level (primary/secondary, college, university, and postgraduate), monthly family income (<₮500,000, ₮500,000-₮1,000,000, ₮1,000,000-₮2 500,000, ₮2 500,000-₮4 500,000, and > ₮4 500,000), marital status (single, married, and other, where other is categorized as divorced/widowed/common law), proportion of income spent on medical expenditure (none, < 5%, 5–15%, 15–25, and > 25%), health habits (smoking and self-perceived adequacy of exercise), and satisfaction of social health insurance (yes/no). The question “Are you a current smoker?” had three response options: nonsmoker, past smoker, and current smoker. “Past smokers” were respondents who used to smoke but have quit; respondents who have never smoked were considered “nonsmokers.” Adequate exercise was measured using the question “Do you think you have adequate exercise each week?” (150 min of moderate activity or 75 min of aerobic activity per week was considered adequate exercise). We only used satisfaction of social health insurance in the models instead of all other perceptions on social health insurance due to high collinearity among these variables, and the model evaluation based on Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion suggested no additional model improvement when all 4 variables on perception were added.

Data quality

We worked with the Mongolian National Chamber of Commerce and Industry, which provided us with a reliable sampling frame. The pretest was performed twice among workers from different fields and professions to ensure that the respondents understood the questions accurately. Within each organization, at least one staff member was assigned by the company to facilitate data collection. Typically, the human resource officers were the staff members assigned to facilitate data collection because they would be more likely to understand the company culture and feasibility of the data collection process. To increase response quality and minimize missing data, we asked the Chief Executive Officers or managers of all organization to allow employees to complete the questionnaire at a particular time. We trained a professional research team from Ach Medical University to screen questionnaire responses before entering the data. Raw data were entered into computers by two independent individuals and were compared to ensure accurate data entry.

Statistical methods

Given that a WTP being zero would not indicate negative WTP (it is reasonable to assume the lowest value a person’s WTP can take is zero.), we performed a 2-part model with the dependent variable divided into an intensive margin and an extensive margin. The density of WTP denoted as gi(.) is defined as follows:

where yi is WTP for an individual I, f0 is the density of yi when yi = 0, fc is the conditional density of yi when yi > 0, x is a vector of covariates, and f0(0 ∣ yi = 0, xi) = 1.

We use logit for the first part and ordinary least squares (OLS) for the second part. Thus,

where α denotes the vector for the first-part logit model, and β is the vector of parameters for the second-part model. The full marginal effect of the covariates needs to consider both the extensive margin (effect of probability that WTP > 0, ie, willingness to participate in the program) and the intensive margin (effect on the mean of WTP conditional on WTP > 0). The full marginal effect can be solved with the derivative of E (yi|xi) using the chain rule as follows:

We retained interaction terms that were statistically significant in at least any part (logit and OLS) of the 2-part model and dropped the terms that were not significant to ensure that the model was parsimonious. All analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (version 15.0, StataCorp, TX, USA).

Results

Table 1 provides a comparison of the sample characteristics between genders. Willingness to participate in the first bit and satisfaction with the current social health insurance were not significantly different between genders. Most male and female participants were married. Approximately 12% of women spent > 25% of their income on medical expenditure, and the corresponding percentage was only 6.4% for men.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by gender

| Female (n = 799) | Male (n = 858) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n % | n % | ||||

| Age (Mean, SD) | 34.8 | 9.5 | 33.1 | 9.3 | < 0.001 |

| Willingness to participate in the first bid | 0.677 | ||||

| No | 509 | 63.7 | 555 | 64.69 | |

| Yes | 290 | 36.3 | 303 | 35.31 | |

| Industry | < 0.001 | ||||

| Mining and quarrying | 30 | 3.75 | 47 | 5.48 | |

| Processing industries | 198 | 24.78 | 223 | 25.99 | |

| Electricity | 59 | 7.38 | 113 | 13.17 | |

| Construction | 20 | 2.5 | 47 | 5.48 | |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 164 | 20.53 | 140 | 16.32 | |

| Transportation | 38 | 4.76 | 69 | 8.04 | |

| Information and communication | 61 | 7.63 | 74 | 8.62 | |

| Finance and insurance | 35 | 4.38 | 34 | 3.96 | |

| Public administration | 77 | 9.64 | 55 | 6.41 | |

| Education services | 61 | 7.63 | 28 | 3.26 | |

| Health care | 56 | 7.01 | 28 | 3.26 | |

| Total monthly family income | 0.013 | ||||

| < 500,000 | 81 | 10.14 | 78 | 9.09 | |

| 500,000-1,000,000 | 280 | 35.04 | 371 | 43.24 | |

| 1,000,000-2,500,000 | 358 | 44.81 | 323 | 37.65 | |

| 2,500,000-4,500,000 | 64 | 8.01 | 69 | 8.04 | |

| > 4,500,000 | 16 | 2 | 17 | 1.98 | |

| Satisfied with SHI | 0.097 | ||||

| No | 553 | 69.21 | 561 | 65.38 | |

| Yes | 246 | 30.79 | 297 | 34.62 | |

| Education | < 0.001 | ||||

| Primary / Secondary | 160 | 20.03 | 261 | 30.42 | |

| College | 67 | 8.39 | 95 | 11.07 | |

| University | 458 | 57.32 | 427 | 49.77 | |

| Postgraduate | 114 | 14.27 | 75 | 8.74 | |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Single | 222 | 27.78 | 194 | 22.61 | |

| Married | 487 | 60.95 | 608 | 70.86 | |

| Other | 90 | 11.26 | 56 | 6.53 | |

| Proportion of income spent on medical care | < 0.001 | ||||

| none | 261 | 32.67 | 424 | 49.42 | |

| < 5% | 144 | 18.02 | 159 | 18.53 | |

| 5–15% | 195 | 24.41 | 143 | 16.67 | |

| 15–25% | 106 | 13.27 | 77 | 8.97 | |

| > 25% | 93 | 11.64 | 55 | 6.41 | |

| Self-rated health | < 0.001 | ||||

| Very good | 41 | 5.13 | 98 | 11.42 | |

| Good | 394 | 49.31 | 468 | 54.55 | |

| Fair | 340 | 42.55 | 262 | 30.54 | |

| Poor | 21 | 2.63 | 26 | 3.03 | |

| Very poor | 3 | 0.38 | 4 | 0.47 | |

| Smoking status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Nonsmoker (base) | 656 | 82.1 | 305 | 35.55 | |

| Past smoker | 48 | 6.01 | 88 | 10.26 | |

| Current smoker | 95 | 11.89 | 465 | 54.2 | |

| Adequate exercise | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 565 | 70.71 | 453 | 52.8 | |

| Don’t know | 106 | 13.27 | 127 | 14.8 | |

| Yes | 128 | 16.02 | 278 | 32.4 | |

Perception of the current social health insurance

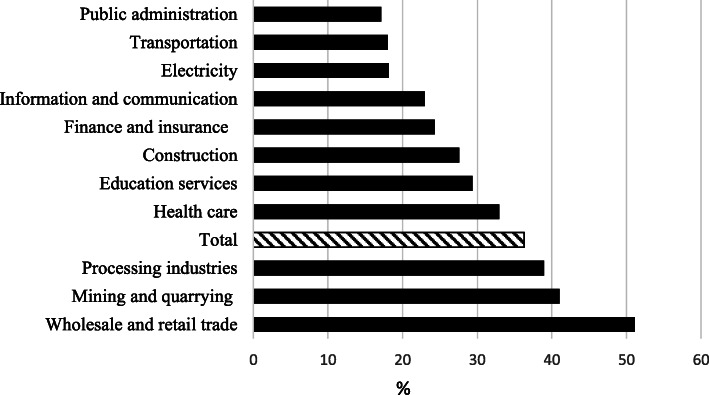

Figure 2 shows the percentage of satisfaction for the current social health insurance stratified by industry. Overall, < 40% of the participants were satisfied with the current system, but when the study population was stratified by industry, a wide range of satisfaction rate was observed, ranging from 17.1% in public administration to 51.1% in the wholesale and retail trade.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of the total participants (n = 1657) satisfied with the social health insurance stratified by industry

Regarding the most desirable aspect of social health insurance, “convenience and ease of access” ranked the highest at 34.27%, followed by “low premium” (29.8%). Only 15.1% of the respondents chose “service quality.” The remaining respondents chose “other” (not specified). Not surprisingly, 40.3% of the respondents selected “low quality” as the most undesirable aspect of the current social health insurance. Regarding the one aspect of social health insurance that the respondent wished to change, 38.1% responded “service,” and 23.22% responded “quality,” representing the top 2 categories of the responses. Table 2 shows perception of social health insurance by whether the subject is willing to participate in the first bid.

Table 2.

Perceptions on social health insurance by willingness to participate in the first bid

| Total | Willingness to participate in the first bid | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Are you satisfied with social health insurance? (n = 1657) | 0.003 | ||||||

| No | 1114 | 67.23 | 743 | 69.83 | 371 | 62.56 | |

| Yes | 543 | 32.77 | 321 | 30.17 | 222 | 37.44 | |

| Please tick one best thing you like about social health insurance (n = 1608) | 0.196 | ||||||

| Premium | 479 | 29.79 | 305 | 29.7 | 174 | 29.95 | |

| Service quality | 243 | 15.11 | 158 | 15.38 | 85 | 14.63 | |

| Convenient and easy access | 551 | 34.27 | 336 | 32.72 | 215 | 37.01 | |

| Other | 335 | 20.83 | 228 | 22.2 | 107 | 18.42 | |

| Please tick one worst thing you dislike about social health insurance (n = 1608) | 0.548 | ||||||

| Premium | 169 | 10.51 | 104 | 10.09 | 65 | 11.27 | |

| Service quality | 648 | 40.3 | 414 | 40.16 | 234 | 40.55 | |

| Convenient and easy access | 583 | 36.26 | 371 | 35.98 | 212 | 36.74 | |

| Other | 208 | 12.94 | 142 | 13.77 | 66 | 11.44 | |

| What would you like to improve in the social health insurance system if you had a chance to do so? (n = 1628) | 0.529 | ||||||

| Service | 620 | 38.08 | 400 | 38.39 | 220 | 37.54 | |

| Quality | 378 | 23.22 | 231 | 22.17 | 147 | 25.09 | |

| Price | 132 | 8.11 | 84 | 8.06 | 48 | 8.19 | |

| Health care provider | 376 | 23.1 | 242 | 23.22 | 134 | 22.87 | |

| Other | 122 | 7.49 | 85 | 8.16 | 37 | 6.31 | |

WTP for parallel private health insurance

Table 3 shows the estimates from the 2-part model. We present the log odds rather than the odds ratio (OR) for the logit part as the model involved interactions, rendering OR difficult to interpret. As expected, higher household income was associated with higher log odds of participation (P < .05). Medical expenditure of > 25% of one’s income was associated with higher WTP for participation (₮13,784, P < .05). Significant interactions were observed between gender and 3 variables—proportion of income spent on medical expenditure, smoking status, and exercise habits. These effects were more interpretable using marginal effects (Table 4).

Table 3.

Two-part model for WTP for the supplementary private health insurance

| First part logit | Second part OLS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participate | SE | WTP | SE | |||

| Age | −0.014 | 0.007 | * | 193 | 150 | |

| Sex (male) | −1.125 | 0.311 | *** | 9697 | 6383 | |

| Household income | 0.214 | 0.096 | * | 182 | 1855 | |

| Sex*household income | 0.248 | 0.132 | 1101 | 2538 | ||

| Industry | ||||||

| Mining and quarrying | ||||||

| Processing industries | 0.199 | 0.278 | 6992 | 5897 | ||

| Electricity | 0.477 | 0.313 | − 620 | 6538 | ||

| Construction | 0.909 | 0.367 | * | 6542 | 7281 | |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 0.559 | 0.292 | 12,768 | 6036 | * | |

| Transportation | 0.219 | 0.333 | 2543 | 7025 | ||

| Information and communication | 0.509 | 0.314 | − 3334 | 6528 | ||

| Finance and insurance | 0.966 | 0.358 | ** | 4586 | 6743 | |

| Public administration | −0.168 | 0.334 | − 898 | 7328 | ||

| Education services | 1.161 | 0.352 | ** | 2977 | 6906 | |

| Health care | 0.282 | 0.353 | 1867 | 7428 | ||

| Satisfied with SHI | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.416 | 0.122 | − 1426 | 2475 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Primary/ Secondary | ||||||

| College | −0.125 | 0.212 | 6543 | 4482 | ||

| University | 0.147 | 0.149 | − 1496 | 3114 | ||

| Postgraduate | 0.012 | 0.222 | − 2048 | 4595 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | ||||||

| Married | −0.102 | 0.139 | − 347 | 2776 | ||

| Other | −0.390 | 0.228 | 1232 | 4874 | ||

| Proportion of income spent on medical care | ||||||

| none | ||||||

| < 5% | 0.119 | 0.224 | 5549 | 4430 | ||

| 5–15% | −0.117 | 0.209 | 1202 | 4237 | ||

| 15–25% | −0.381 | 0.267 | − 3162 | 5700 | ||

| > 25% | −0.164 | 0.280 | 13,784 | 5869 | * | |

| Sex* Proportion of income spent on medical care | ||||||

| < 5%* Male | 0.123 | 0.305 | 2749 | 6040 | ||

| 5–15%* Male | 0.743 | 0.297 | * | − 1025 | 5936 | |

| 15–25%* Male | 1.324 | 0.374 | *** | 4576 | 7545 | |

| > 25%* Male | 0.351 | 0.433 | −13,080 | 9208 | ||

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Very good | ||||||

| Good | 0.007 | 0.206 | − 1860 | 4088 | ||

| Fair | −0.216 | 0.225 | 592 | 4525 | ||

| Poor | −0.499 | 0.412 | 2055 | 8869 | ||

| Very poor | 0.389 | 0.816 | −13,970 | 16,288 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | ||||||

| Past smoker | 0.488 | 0.323 | 8433 | 5829 | ||

| Current smoker | 0.153 | 0.241 | 265 | 4846 | ||

| Sex# Smoking status | ||||||

| Male* Past smoker | 0.091 | 0.416 | −15,871 | 7689 | * | |

| Male* Current smoker | −0.023 | 0.291 | − 9143 | 5870 | ||

| Adequate exercise | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Don’t know | −0.606 | 0.249 | * | 3478 | 5302 | |

| Yes | −0.143 | 0.217 | 4363 | 4417 | ||

| Sex* Adequate exercise | ||||||

| Male* Don’t know | 0.869 | 0.334 | ** | − 5121 | 6944 | |

| Male* Yes | 0.494 | 0.275 | − 5481 | 5546 | ||

| Constant term | −1.261 | 0.423 | * | 36,982 | 9141 | *** |

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001

Table 4.

Marginal effects

| Total | Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effect | SE | Marginal effect | SE | Marginal effect | SE | ||||

| Age | −66 | 86 | −64 | 89 | −74 | 88 | |||

| Sex (male) | 292 | 1628 | |||||||

| Household income | 3482 | 816 | *** | 2101 | 1145 | 4987 | 1130 | *** | |

| Industry | |||||||||

| Mining and quarrying (base) | |||||||||

| Processing industries | 3749 | 2743 | 3892 | 2830.9 | 3772 | 2817 | |||

| Electricity | 3654 | 3179 | 3691 | 3276 | 3882 | 3254 | |||

| Construction | 10,875 | 4368 | * | 11,063 | 4473 | * | 11,257 | 4480 | * |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 9597 | 3089 | ** | 9903 | 3173 | ** | 9719 | 3188 | ** |

| Transportation | 2519 | 3365 | 2589 | 3475 | 2591 | 3442 | |||

| Information, communication | 2894 | 3161 | 2878 | 3259 | 3167 | 3236 | |||

| Finance and insurance | 10,542 | 4127 | * | 10,684 | 4202 | * | 10,983 | 4251 | * |

| Public administration | − 1433 | 3079 | − 1469 | 3181 | − 1493 | 3152 | |||

| Education services | 11,718 | 4109 | ** | 11,799 | 4212 | ** | 12,306 | 4244 | ** |

| Health care | 2841 | 3630 | 2907 | 3738 | 2947 | 3723 | |||

| Satisfied with SHI | |||||||||

| No (base) | |||||||||

| Yes | 3429 | 1502 | * | 3456 | 1546 | * | 3628 | 1538 | * |

| Education | |||||||||

| Primary/ Secondary (base) | |||||||||

| College | 933 | 2586 | 1028 | 2667 | 824 | 2630 | |||

| University | 843 | 1777 | 829 | 1821 | 923 | 1811 | |||

| Postgraduate | − 598 | 2567 | − 634 | 2640 | − 573 | 2616 | |||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Never married (base) | |||||||||

| Married | − 1097 | 1687 | − 1115 | 1727 | − 1140 | 1724 | |||

| Other | − 3224 | 2600 | − 3259 | 2686 | − 3398 | 2650 | |||

| Proportion of income spent on medical care | |||||||||

| none | |||||||||

| < 5% (base) | 4227 | 1934 | * | 3418 | 2906 | 4981 | 2584 | ||

| 5–15% | 2751 | 1811 | − 626 | 2498 | 6079 | 2645 | * | ||

| 15–25% | 2975 | 2331 | − 4327 | 2866 | 10,004 | 3651 | ** | ||

| > 25% | 2548 | 2794 | 3371 | 3805 | 1909 | 3982 | |||

| Self-rated health | |||||||||

| very good (base) | |||||||||

| good | − 638 | 2537 | − 672 | 2605 | − 614 | 2587 | |||

| fair | − 1871 | 2749 | − 1891 | 2830 | − 1970 | 2797 | |||

| poor | − 4009 | 4580 | − 4062 | 4732 | − 4225 | 4660 | |||

| very poor | − 2515 | 9580 | − 2795 | 9816 | − 2134 | 9760 | |||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Nonsmoker (base) | |||||||||

| Past smoker | 5697 | 2829 | * | 8618 | 4627 | 3047 | 3386 | ||

| Current smoker | −186 | 1772 | 1527 | 2951 | − 1788 | 2016 | |||

| Adequate exercise | |||||||||

| No (base) | |||||||||

| Don’t know | − 1105 | 1850 | − 4350 | 2678 | 2014 | 2731 | |||

| Yes | 1632 | 1699 | 285 | 2737 | 3109 | 2152 | |||

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001

The final effect of each variable on WTP is better interpreted using marginal effects, as both the logit part on likelihood of participation and WTP for participation should be considered. Regarding marginal effects, household income had an overall positive effect on WTP (P < .001), and the marginal effect of income for men was higher than that for women. Being satisfied with social health insurance had a higher WTP by approximately ₮1500 (P < .05). As expected, a higher proportion of income spent on medical expenditure was associated with a higher WTP for both genders (P < .05). However, the marginal effects differed by gender: for men, but not for women, a medical expenditure of 5–25% of income had a positive marginal effect on WTP. Past smokers had a higher WTP by approximately ₮5700 than nonsmokers (P < .05). The predicted WTP for men and women was ₮16,369 (SE = 1196, P < .001) and ₮16,661 (SE = 1074, P < .001), respectively.

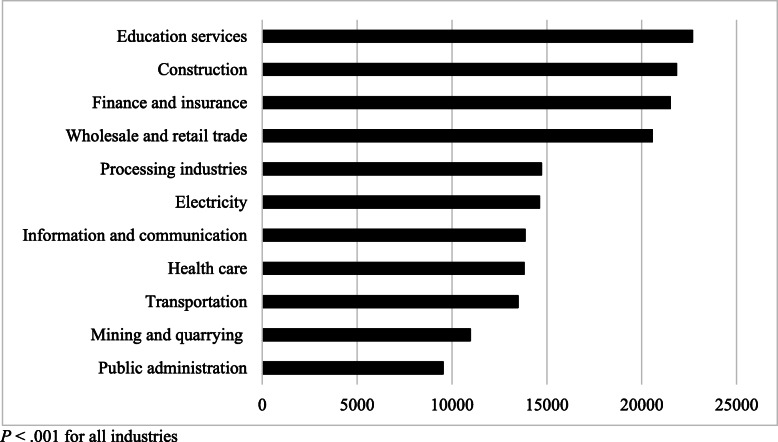

Variation by industry

From the 2-part model, willingness to participate in the first bid and WTP for participation varied by industry. Compared with the mining industry, the participants from the construction, finance, and education industries had significantly higher odds of willingness to participate. The participants from the wholesale industry had a higher WTP than those from the mining industry (P < .05).

Figure 3 shows the ranked predicted WTP given both willingness to participate and WTP for participation (P < .001 for all industries). The education industry had the highest predicted WTP ₮22,675 (SE = 3346), and the mining industry and public administration had the lowest.

Fig. 3.

Predicted WTP by industry. P < .001 for all industries

Discussion

This study is the first to highlight the possibility of introducing parallel PHI as a complement to the existing SHI system in Mongolia. Mongolia’s healthcare system has rarely been studied. We found that the proportion of workers satisfied with the current social health insurance system was almost equal to that of WTP for the supplementary private health insurance (31% vs. 35%). The predicted WTP for the parallel private health insurance for men and women was Mongolian Tugrik (₮)16,369 (p < 0.001) and ₮16,661 (p < 0.001), respectively. The highest predicted WTP was found for workers from the education industry (₮22,675, SE = 3346). Income and past or current medical expenditures were significantly associated with WTP.

The public versus private health care financing debate continues in academic and policy circles worldwide [33]. The role of private health insurance differs depending on the country’s wealth and health service development among low- and middle-income countries [34]. Similar hybrid financing systems exist in other countries. For example, in the United Kingdom, approximately 11% of people have had parallel private insurance [35]. Australia and Canada [33] also have similar systems. The results of previous studies in Mongolia have indicated high out-of-pocket expenditure [8, 9], which leads to an immense economic burden on households, leading to poverty [2, 36]. The social health insurance in Mongolia covers mostly inpatient care services, and the coverage is different among public and private health care providers. Services from public health care providers are relatively difficult to access and have inferior quality compared with services from private providers; thus, people are required to pay more for expensive private services. Waiting time is another factor that leads to the use of private health facilities, especially among workers, where time represents the opportunity costs of being sick [37, 38]. Private hospitals that are affiliated with social health insurance still rely heavily on out-of-pocket payments from patients (an average of US$27 per capita on out-of-pocket expenditure) [6, 22]. This amount is most likely unaffordable for an average Mongolian household, given that the average monthly household income was only US$451 in 2018 [22]. The option of financial protection mechanism is very limited and remains a formidable challenge, particularly in developing countries [39].

Empirical results from early studies suggest that demand for health insurance is affected by education [22] and income levels, and the male gender is associated with a higher willingness to pay (WTP) [23, 24]. This prompted us to investigate differences in WTP by gender in Mongolia during the transition period when women had a higher education level [25] but lower wage and fewer job opportunities than men [26]. There are large differences in earnings that cannot be explained by education and experience. The overall gender wage gaps are approximately 10% in all industries [20]. Additionally, early retirement, compared with men, has negative implications for women’s career progression [3]. Moreover, concerning SDG 5 by the United Nations, it is crucial to clarify the current situation on gender equality in Mongolia. Raising awareness of the gender imbalance, especially related to the education level, is essential for policymakers because this topic lies at the intersection of many fields, including education, health, and labor [40], and the position of women is different in different countries [21]. However, the difference between gender in the marginal effect in terms of WTP was not high. This may be because of the current gender imbalances in higher education (14.27% of women had postgraduate education level vs. 8.74% of men, which is also noted in a previous study [40]) and the wage level. By contrast, studies have indicated that men are more willing to pay for health insurance [25].

Income [27, 31], age [27], and medical expenditure burden [27, 31] are essential factors associated with WTP. In our study, the predicted WTP was the lowest in the public administration sector, probably due to the low average income in that sector compared with other industries. Public sector employees may already be enjoying some medical benefits from public health care providers because some government workers have access to specialized medical facilities that provide services only to them on a priority basis. The highest amount stated with the demand of WTP was among workers from education and finance and insurance sectors, which can be attributed to a higher level of education and knowledge of private health insurance [25–27]. We did not find age to be significantly associated with WTP. A previous study reported that WTP decreases with age [25]. This difference may be explained by the fact that the working population in Mongolia is relatively young; hence, the difference between age groups is less salient.

Respondents who were satisfied with the current social health insurance system were more willing to participate than those who were not. The satisfied respondents may have used the social health insurance system before, so they know the benefit of insurance and may plan to increase the service quality and access through the supplementary private health insurance. Health insurance may thus improve the quality of care provided by public health care facilities due to competition with private providers.

This study has some limitations. First, we included only workers from Ulaanbaatar, which may not be generalizable to the entire country. However, 41% of the entire working population lives in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar [22]. Thus, Ulaanbaatar would be the most reasonable place to start such a program in Mongolia. Another limitation can be interviewer bias, as respondents may have equated answering ‘Yes’ to the WTP question as participation and that they are obligated to pay, which can decrease participation in the first bid. This issue, however, is not unique to this study [25].

The Mongolian health care system is underfunded, and its service quality is low, particularly among public health care providers. Improving the health care system is the main priority of the Mongolian government. However, public health sector reform is difficult and time intensive, even in developed countries [41, 42]. In addition, in several Asian countries [43, 44], private health insurance industries are well developed despite efficient public health sectors. Reforming the public health sector however, remins an option.

Policymakers can discuss how to establish a more sustainable health insurance system in Mongolia. We suggest that first, the SHI package should be increased on the basis of the analysis of Mongolian population’s satisfaction, and the quality and access of public health care providers should be improved through competition with private health care providers, and second, public knowledge about the health insurance system should be increased, thus changing the predominantly negative attitude toward health insurance, and allowing private health insurance to complement mandatory social health insurance at the national level through appropriate policy. Because of similarities in the background of the postsocialist countries, our results may be useful for other such countries in the transition period and other developing low- and middle-income countries trying to achieve universal health care coverage. Appropriately managed private health insurance can play a positive role in improving access and equity of health care in developing countries and reducing the risk of poverty due to out-of-pocket health expenditure. In particular, to raise the value of health insurance, policymakers must understand the importance of improving the quality of health care services in Mongolia.

Conclusion

Our study is the first survey-based study for predicted WTP for PHI for the employed population in Mongolia. The employed population, rather than the general population, can be considered the main contributor of healthcare financing in many developing countries; therefore, information on their WTP for PHI is essential for determining the feasibility of the program. To reduce out-of-pocket health expenditure among the working population in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, supplementary parallel health insurance is feasible given that the predicted WTP is around 2.4% of the median salary. However, given high variations among different industries and sectors, different incentives may be required for participation.

Acknowledgments

None

Abbreviations

- UHC

Universal health coverage

- OOP

Out-of-pocket

- PHI

Private health insurance

- NSO

National Statistics Office

- WTP

Willingness to pay

- SDG

Sustainable Development Goals

- CV

Contingent valuation

- OR

Odds ratio

- SE

Standard error

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

OB collected the data, OB and CP analyzed the data. Both authors wrote and approved the manuscript together.

Funding

This study was supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant numbers: 109–2314-B-010-049-MY2). The funder has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to IRB regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written consents to participate were obtained from all participants in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Yang-Ming University (YM107064E-2), Taipei, Taiwan, and by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ach Medical University (12/23), Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tangcharoensathien V, Mills A, Palu T. Accelerating health equity: the key role of universal health coverage in the sustainable development goals. BMC Med. 2015;13:101. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0342-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorjdagva J, Batbaatar E, Svensson M, Dorjsuren B, Kauhanen J. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Mongolia. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:105. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0395-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dashzeveg C, Mathauer I, Enkhee E, Dorjsuren B, Tsilaajav T, Batbayar C. A health financing review of Mongolia with a focus on social health insurance: World Health Organization; 2011.

- 4.Tsevelvaanchig U, Narula IS, Gouda H, Hill PS. Regulating the for-profit private healthcare providers towards universal health coverage: a qualitative study of legal and organizational framework in Mongolia. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2018;33:185–201. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chimed-Ochir O. Patient satisfaction and service quality perception at district hospitals in Mongolia. Ritsumeikan J Asia Pacific Studies. 2012;31:16–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsevelvaanchig U. Regulating for-profit private health care providers in the context of universal health coverage: a case study from Mongolia. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsevelvaanchig U, Gouda H, Baker P, Hill PS. Role of emerging private hospitals in a post-soviet mixed health system: a mixed methods comparative study of private and public hospital inpatient care in Mongolia. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:476–486. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dugee O, Sugar B, Dorjsuren B, Mahal A. Economic impacts of chronic conditions in a country with high levels of population health coverage: lessons from Mongolia. Tropical Med Int Health. 2019;24:715–726. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dugee O, Palam E, Dorjsuren B, Mahal A. Who is bearing the financial burden of non-communicable diseases in Mongolia? J Glob Health. 2018;8:010415. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.010415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dugee O, Munaa E, Sakhiya A, Mahal A. Mongolia’s public spending on noncommunicable diseases is similar to the spending of higher-income countries. Health Aff. 2017;36:918–925. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erlangga D, Suhrcke M, Ali S, Bloor K. The impact of public health insurance on health care utilisation, financial protection and health status in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0219731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colombo F, Tapay N. Private health insurance in OECD countries: the benefits and costs for individuals and health systems. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekhri N, Savedoff W. Private health insurance: implications for developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:127–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gassmann F, Francois D, Zardo Trindade L. Improving labor market outcomes for poor and vulnerable groups in Mongolia. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batchuluun A, Dalkhjav B. Labor force participation and earnings in Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar: National University of Mongolia; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batchuluun A, Lin JY. An analysis of mining sector economics in Mongolia. Glob J Bus Res. 2010;4:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tudev O, Damba G. Insights of the Mongolian labor market. J Bus. 2015;3:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng T-M. Reflections on the 20th anniversary of Taiwan’s single-payer National Health Insurance System. Health Aff. 2015;34:502–510. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shatz HJ, Constant L, Arce FP, Robinson E, Beckman RL, Huang H, Glick P, Ghosh-Dastidar B. Improving the Mongolian labor market and enhancing opportunities for youth. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan T, Aslam M. Mongolia: gender disparities in labor markets and policy suggestions. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pastore F. The gender gap in early career in Mongolia. Int J Manpow. 2010;31(2):188–207.

- 22.NSO . Mongolian statistical information service. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oduniyi OS, Antwi MA, Tekana SS. Farmers’ willingness to pay for index-based livestock Insurance in the North West of South Africa. Climate. 2020;8:47. doi: 10.3390/cli8030047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basaza R, Kyasiimire EP, Namyalo PK, Kawooya A, Nnamulondo P, Alier KP. Willingness to pay for community health insurance among taxi drivers in Kampala City, Uganda: a contingent evaluation. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2019;12:133. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S184872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams R, Chou Y-J, Pu C. Willingness to participate and pay for a proposed national health insurance in St. Vincent and the grenadines: a cross-sectional contingent valuation approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:148. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0806-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jofre-Bonet M, Kamara J. Willingness to pay for health insurance in the informal sector of Sierra Leone. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0189915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nosratnejad S, Rashidian A, Dror DM. Systematic review of willingness to pay for health insurance in low and middle income countries. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yip W. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. 2019. Healthcare system challenges in Asia. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindhjem H, Navrud S. Asking for individual or household willingness to pay for environmental goods?: IIImplication for aggregate welfare measures. Environ Resour Econ. 2009;43:11–29. doi: 10.1007/s10640-009-9261-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delaney L, O’Toole F. Willingness to pay: individual or household? J Cult Econ. 2006;30:305–309. doi: 10.1007/s10824-006-9021-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimamura Y, Matsushima M, Yamada H, Nguyen M. Willingness-to-pay for family-based health insurance: findings from household and health facility surveys in Central Vietnam. Global J Health Sci. 2018;10:24. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v10n7p24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asgary A, Willis K, Taghvaei AA, Rafeian M. Estimating rural households’ willingness to pay for health insurance. Eur J Health Econ. 2004;5:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s10198-004-0233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buckley NJ, Cuff K, Hurley J, McLeod L, Nuscheler R, Cameron D. Willingness-to-pay for parallel private health insurance: evidence from a laboratory experiment. Can J Econ. 2012;45:137–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5982.2011.01690.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ying XH, Hu TW, Ren J, Chen W, Xu K, Huang JH. Demand for private health insurance in Chinese urban areas. Health Econ. 2007;16:1041–1050. doi: 10.1002/hec.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emmerson C, Frayne C, Goodman A. Should private medical insurance be subsidised? 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dorjdagva J, Batbaatar E, Svensson M, Dorjsuren B, Batmunkh B, Kauhanen J. Free and universal, but unequal utilization of primary health care in the rural and urban areas of Mongolia. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:73. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0572-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johar M, Jones G, Keane MP, Savage E, Stavrunova O. The demand for private health insurance: do waiting lists matter?–revisited: Economics Group, Nuffield College, University of Oxford; 2013.

- 38.Besley T, Hall J, Preston I. The demand for private health insurance: do waiting lists matter? J Public Econ. 1999;72:155–181. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(98)00108-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalal BS. Impact of out-of-pocket health care financing and health insurance utilization among the population: a systematic review. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adiya E. Gender equity in access to higher education in Mongolia: University of Pittsburgh; 2010.

- 41.McPake B, Mills A. What can we learn from international comparisons of health systems and health system reform? Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:811–820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berman P, Bossert T. A decade of health sector reform in developing countries: what have we learned. Washington: UNAID; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu T-C, Chen C-S. An analysis of private health insurance purchasing decisions with national health insurance in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:755–774. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeon B, Kwon S. Effect of private health insurance on health care utilization in a universal public insurance system: a case of South Korea. Health Policy. 2013;113:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to IRB regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.