Abstract

Objective:

To explore the relationship between tumor size and response to combined anti-vascular targeted therapy using the anti-angiogenesis inhibitor, bevacizumab, and the tubulin-binding vascular disrupting agent, fosbretabulin.

Methods:

An exploratory, post-hoc analysis of the randomized phase II trial, Gynecologic Oncology Group-0186I, was performed. One hundred and seven patients with recurrent ovarian carcinoma, treated with up to 3 prior regimens, were randomized to bevacizumab 15 mg/kg body weight with or without intravenous fosbretabulin 60 mg/m2 body surface area every 21 days until progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary analysis favored the combination (HR 0.69; 95% CI, 0.47–1.00; p=0.049) [Monk BJ, et al J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2279–86]. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the treatment effect in various subpopulations.

Results:

With extended follow-up, the median PFS for bevacizumab plus fosbretabulin was 7.6 months as compared to 4.8 months with bevacizumab alone (HR 0.74; 90% CI, 0.54–1.02). Overall survival was similar in the experimental and control arms (25.2 vs 24.4 mos, respectively, HR 0.85;90% CI, 0.59–1.22; p=0.461). Eighty-one patients had measurable disease and median tumor size was 5.7 cm. In the ≤5.7 cm subgroup, the HR for progression or death was 0.77 (90% CI 0.45–1.31). Patients with tumors >5.7cm (n=40) had a HR for progression or death of 0.55; 90% CI, 0.32–0.96; p=0.075).

Conclusions:

Although no significant survival benefit was observed, the trend showing a reduced HR for progression or death with increasing tumor size when fosbretabulin is added to bevacizumab compared to bevacizumab alone warrants further study.

Keywords: fosbretabulin, vascular disrupting agent, bevacizumab, ovarian cancer

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic cancer among women in the United States, with 21,750 new cases and approximately 13,940 deaths due to disease expected to occur in 2020.1 The vast majority of patients with advanced disease achieve complete clinical remission following cytoreductive surgery and adjuvant platinum-and-taxane based systemic chemotherapy. Unfortunately, as a result of acquired drug resistance and lack of effective maintenance therapy for the majority of patients, most patients suffer disease recurrence. Available therapies in the recurrent setting, even for women with platinum-sensitive disease, are unlikely to cure patients, with most studies reporting 10-year disease-specific survival to be less than 10%. Newer, active and tolerable combinations are required.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has emerged as a validated target in advanced ovarian carcinoma. The fully humanized monoclonal antibody, bevacizumab, inhibits tumor angiogenesis by sequestering the VEGF-A ligand and preventing its interaction with the VEGF receptor (VEGFR). Nine phase III randomized trials of anti-angiogenesis therapy employing five different drugs and exploiting two distinct pro-angiogenic pathways, have met their primary endpoints by significantly improving progression-free survival (PFS) in women with newly diagnosed or recurrent platinum sensitive and platinum resistant ovarian carcinoma.2–11 Bevacizumab was studied in five of these trials.3,4,7,8,10 The United States Food and Drug Administration approved the combination of chemotherapy plus bevacizumab for patients with platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive ovarian carcinoma in 2014 and 2016, respectively. On June 13, 2018 the label for bevacizumab was expanded to also include frontline and maintenance therapy for women with newly diagnosed advanced disease based on the PFS endpoint from Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Protocol 0218. This regulatory milestone needs to be set against a backdrop of no overall survival (OS) advantage,12 the absence of a predictive biomarker for bevacizumab use, and potential for significant adverse events, including gastrointestinal wall disruption. Accordingly, an important clinical research priority is to clarify the role of anti-angiogenesis therapy in ovarian cancer.

Unlike bevacizumab and small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors that exert their effects along the VEGF-dependent axis and prevent neovascularization at the tumor perimeter, tubulin-binding vascular disruptive agents (VDAs) such as fosbretabulin target existing tumor vasculature.13 Due to lack of pericyte coverage, the tumor blood supply is fragile and leaky, requiring tubulin to provide an endoskeleton to ‘shape’ the vasculature. Fosbretabulin engages tubulin causing the endothelial cells to assume a spherical conformation.14 This leads to blood vessel congestion and occlusion, greatly reduced blood flow, and ultimately irreversible ischemia and tumor cell necrosis in the central core due to cessation of blood flow.14 When combined with anti-angiogenesis therapy such as bevacizumab, the ongoing cellular necrosis within the tumor is accompanied by prevention of vessel regrowth at the tumor rim or perimeter.

Nathan et al reported the safety and tolerability of bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) plus fosbretabulin (63 mg/m2) every 14 days.14 In the open-label, randomized phase II trial, GOG-0186I (NCT01305213), women with recurrent ovarian cancer were treated with bevacizumab with and without fosbretabulin.15 As reported in the primary publication, treatment with the combination reduced the hazard of progression by 31%.15 We sought to study the hypothesis that combined targeted anti-vascular therapy would have its greatest impact on bulky disease which is characterized by an existing, relatively dense vascular network.

METHODS

Patients eligible for enrollment on GOG-0186I included those 18 years or older with GOG performance status of 0 or 1 measurable disease per RECIST 1.1 or detectable persistent or recurrent EOC, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma with documented disease progression after one prior platinum-based chemotherapeutic regimen and no more than two additional cytotoxic regimens for management of recurrent or persistent cancer. Patients with either platinum-sensitive (platinum-free interval (PFI) > 182 days) or platinum-resistant (PFI ≤ 182 days) disease were eligible.15 Anti-angiogenic therapy was permitted as part of primary therapy only. PFS was the primary endpoint. Patients were stratified by presence or absence of measurable disease, prior use of bevacizumab, and most recent platinum-free interval (> 365 days vs. > 182 days ≤ 365 days, vs. ≤ 182 days). Laboratory parameters required for eligibility can be found in the GOG-0186I master protocol available at www.gynecologicvoncology-online.net.

Bevacizumab was administered at 15 mg/kg as a continuous intravenous (IV) infusion once every three weeks. Patients randomly assigned to fosbretabulin received 60 mg/m2 IV over 10 minutes on day 1 of each cycle after bevacizumab. Before fosbretabulin was administered, all patients received oral or IV dexamethasone (8 mg) and oral acetaminophen (650 mg) one hour before infusion. Details concerning anaphylaxis precautions, management of infusion reactions, management of hypertension, and dose modifications can be found in the GOG-0186I master protocol

As reported in the original publication, the study enrolled 103 evaluable patients and the first intention-to-treat analysis was triggered after observing 88 PFS events. Following a data cutoff on March 3, 2014, it was reported that adding fosbretabulin to bevacizumab appeared to prolong PFS compared with bevacizumab alone (median PFS 4.8 mos for bevacizumab alone vs 7.3 mos for bevacizumab plus fosbretabulin; HR 0.69; two-sided 90% CI, 0.47–1.00; 1-sided p=0.049).15 Details concerning adverse events, including hypertension (grade >3) which was more commonly observed in the combination arm (35% vs 20%), may also be found in the primary manuscript.15

With extended follow-up, the database was locked again in February 2017 for these ancillary analyses. Interestingly, in GOG-186I, there was a non-significant trend for more patients with measurable disease to respond to the combination of bevacizumab plus fosbretabulin. Because measurable disease encompasses “bulky tumors” and there is no clear definition of what constitutes bulky disease, we examined the hypothesis further by studying tumor size. All measurable lesions up to a maximum of two lesions per organ and five lesions in total, representative of all involved organs, were identified as target lesions and recorded and measured at baseline. RECIST version 1.1 was used to evaluate the clinical endpoints.

To avoid the data to appear highly skewed when tumor size is evaluated as a continuous variable, we chose to dichotomize tumor size. Through dichotomization we avoided the potential for a few influential cases to overwhelm the analysis and cause misrepresentation of the general findings. Furthermore, it is easier to convey the potential impact of a specific variable on PFS if the data is aggregated in groups.

The sum of the longest diameter (SLD) at baseline was used to analyze the groups of patients above and below the median baseline SLD. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan Meier method and a Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the effect of treatment within each population.16,17

RESULTS

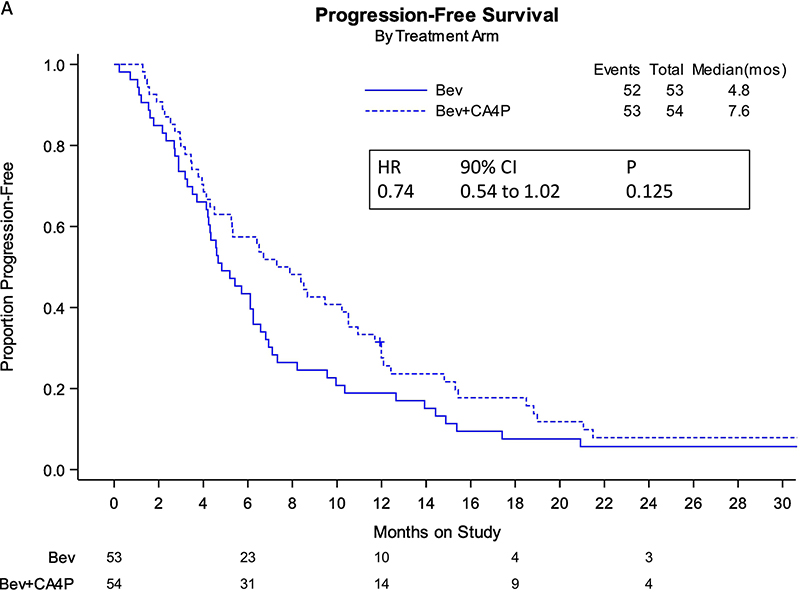

Nearly three years following the initial analysis, 105 PFS events had occurred. For the intention-to-treat study population, relative to single-agent bevacizumab, the addition of fosbretabulin to bevacizumab was associated with nearly a 3-month improvement in median PFS (7.6 vs 4.8 mos; HR 0.74; 90% CI, 0.54–1.02; 2-sided p=0.125, and one-sided p=0.063) (primary endpoint, Figure 1A). Following 84 deaths, there was no survival advantage conferred by the combined targeted antivascular regimen relative to bevacizumab alone (secondary endpoint, Figure 1B). Table 1 compare the schanges in median PFS and in OS between the two treatment arms of GOG-0186I.

FIGURE 1:

Panel A. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting progression-free survival (PFS) by intention-to-treat with extended follow-up (entire study population).

Panel B. Kaplan-Maier curves depicting overall survival (OS) curves by intention-to-treat with extended follow-up (entire study population).

Bev: bevacizumab; CA4P: fosbretabulin; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; mos: months

Table 1.

Comparison of Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival analyses in GOG-0186I.

| Populations Studied | N | Δ Median PFS* | HR | P |

| ITT study population (March 2014) | 107 | 2.5 | 0.69 | 0.098 |

| Platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer | 80 | 1.5 | 0.67 | 0.139 |

| Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer | 27 | 3.3 | 0.57 | 0.010 |

| ITT study population (February 2017) | 107 | 2.8 | 0.74 | 0.125 |

| Platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer | 80 | 1.9 | 0.84 | 0.436 |

| Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer | 26** | 3.2 | 0.49 | 0.091 |

| Measurable disease February 2017 | 81 | 3.7 | 0.65 | 0.057 |

| Tumor size ≤ median (5.7 cm SLD) | 40 | 2.2 | 0.77 | 0.418 |

| Tumor size > median (5.7 cm SLD) | 41 | 6.2 | 0.55 | 0.075 |

| Populations Studied | N | Δ Median OS* | HR | P |

| ITT study population (April 2015)** | 107 | 2.6 | 0.85 | n/a |

| ITT study population (February 2017) | 107 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.461 |

| Platinum sensitive ovarian cancer | 80 | −1.9 | 0.826 | 0.532 |

| Platinum resistant ovarian cancer | 26*** | 1.2 | 0.802 | 0.581 |

| Measurable disease (February 2017) | 81 | 6.6 | 0.80 | 0.391 |

| Tumor size ≤ median (5.7 cm SLD) | 40 | −10.8 | 1.245 | 0.626 |

| Tumor size > median (5.7 cm SLD) | 41 | 10.1 | 0.521 | 0.095 |

denotes the change in median months progresssion-free or median months alive between the bevacizumab and bevacizumab plus fosbretabulin treatment arms in GOG-0186I; the single asterisk next to Median OS.

an earlier analysis of overall survival was performed during April 2015

in the updated analysis one patient who had originally been classified as having platinum-resistant disease was reclassified to having indeterminate platinum status and therefore not included in the February 2017 analysis of platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant cohorts

PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; ITT: intent to treat analysis; Δ: change; HR: hazard ratio; SLD: single longest diameter; P values listed are 2-sided

Among patients determined to be platinum-sensitive (n=80), the improvement in median PFS (8.1 vs 6.2 mos) did not reach statistical significance for the combination regimen compared to bevacizumab alone (Figure 2A). However, among the 26 women with platinum-resistant relapse, a potential 3.2 month improvement in median PFS was associated with administration of bevacizumab plus fosbretabulin (HR 0.49; 90% CI, 0.24–0.98) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2:

Panel A. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting progression-free survival (PFS) by intention-to-treat of the platinum-sensitive subpopulation.

Panel B. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting progression-free survival (PFS) by intention-to-treat of the platinum-resistant subpopulation.

Bev: bevacizumab; CA4P: fosbretabulin; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; mos: months

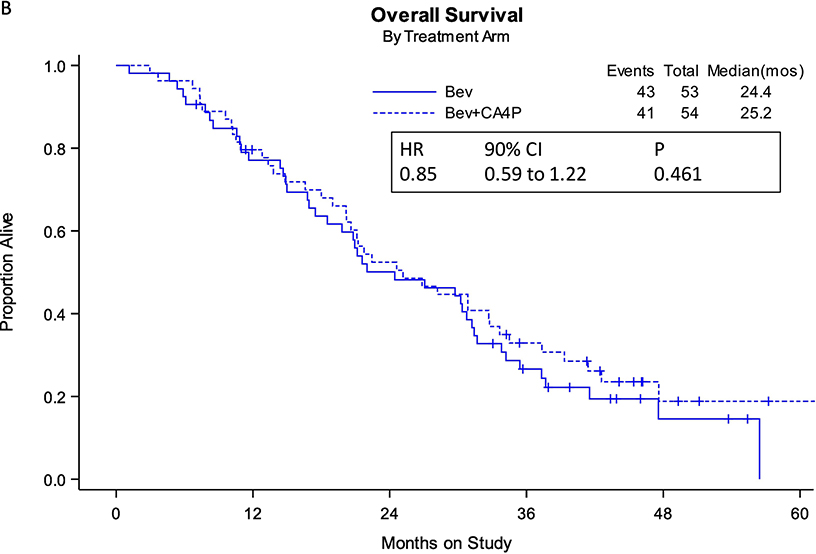

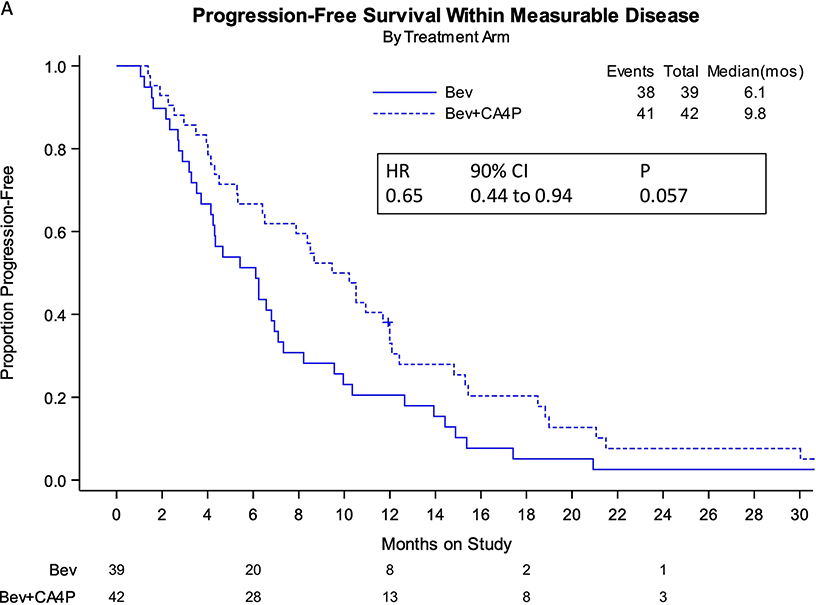

Eighty-one women with measurable disease, as defined by RESIST 1.1 criteria, were studied for treatment effect on the PFS endpoint. The incorporation of fosbretabulin with bevacizumab reduced the hazard of progression by 40% (9.8 vs 6.1 mos; HR 0.65; 90% CI, 0.44–0.94; 2-sided p=0.057) (Figure 3A). Treatment with the combination was associated with an approximate 6.6 month longer median survival in women with measurable disease, but this was not statistically significant (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3:

Panel A. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting progression-free survival (PFS) by intention-to-treat for patients with measureable disease.

Panel B. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting overall survival (OS) by intention-to-treat for patients with measureable disease.

Bev: bevacizumab; CA4P: fosbretabulin; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; mos: months

The median baseline tumor size for the entire study population was 5.7 cm (n=81, range = 1–19.3 cm, standard deviation of 4.3, skewness of 0.89). Patients with a maximal tumor size less than or equal to the median had a non-significant trend favoring improved PFS with the combination regimen (9.1 vs. 6.9 months) (Figure 4A). Those with bulky disease (i.e. maximal tumor diameter greater than the median) treated with bevacizumab and fosbretabulin experienced a six-month improvement in median PFS (10.5 vs 4.3 mos; HR 0.55; 90% CI, 0.32–0.96) (Figure 4B). For the smaller tumor sizes, the objective response rate was 43% regardless of treatment. For tumors > 5.7 cm, the objective response rate was 15% for patients treated on the bevacizumab alone arm, and 35% for those treated with the combination regimen (Table 2). These observations are consistent with the PFS findings.

FIGURE 4:

Panel A. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting progression-free survival (PFS) by intention-to-treat for patients with tumor size less than or equal to the median 5.7 cm.

Panel B. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting progression-free survival (PFS) by intention-to-treat for patients with tumor size greater than the median 5.7cm.

Bev: bevacizumab; CA4P: fosbretabulin; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; mos: months

Table 2:

Objective response rates (RR) for tumors according to tumor size and treatment regimen.

| Tumor Size | Bevacizumab N (%) | Bevacizumab + Fosbretabulin N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | RR | N | % | RR | |

| ≤5.7 cm | 19 | 17.8 | 43% | 22 | 20.6 | 43% |

| >5.7 cm | 20 | 18.7 | 15% | 20 | 18.7 | 35% |

Additonal clinical biomarkers were studied to determine whether any associations with clinical endpoints were manifest. Regarding cell type, 85% of the population had high grade serous tumors and therefore with other histologic types appearing at relatively low frequency, the analyses were not informative. Similarly, when considering site of disease, we encountered a similar situation with too few numbers when metastases were assigned to the vagina, pelvis, abdomen, liver and lung.

DISCUSSION

The current post-hoc analysis suggests that the near 3-month improvement in median PFS attributed to the addition of fosbretabulin to anti-angiogenic therapy is sustained over extended follow-up in this population of women with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. The effect is particularly striking in the platinum-resistant subpopulation. A precedent for the observations observed in GOG-0186I can be found in preclinical studies.

Inglis et al studied the tubulin-targeting VDA, BNC105, in animal models of breast and renal cell carcinoma.18 BNC105-induced hypoxia led to upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha, GLUT-1, and the VEGF signaling axis. When the VDA was combined with bevacizumab, tumor vascular recovery was significantly hindered. When BNC106 was administered alone or together with the VEGFR1–3 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, pazopanib, a significant increase in animal survival was achieved with the combination (p<0.0001).18 Siemann and Shi studied treatment of human clear cell carcinomas that had been established in nude mice.19 The animals received bevacizumab alone, a tumor VDA alone, or a combination of bevacizumab and tumor VDA. Treatment with the combination delayed tumor growth by 18 days as compared with six to eight days with a monotherapy. Finally, Nguyen et al reported prolonged survival of mice with colorectal cancer liver metastasis with a combination of the VDA, OXi4503, and the antiangiogenic agent, sunitinib.19

Another noteworthy observation in our exploratory analyses was an improved hazard of progression seen with increasing tumor size. This feature may be unique to VDAs and essentially represents the “inverse” of the volume-response relationship associated with conventional therapeutic modalities. Our observations are consistent with those reported by others.

Using a rhabdomyosarcoma rat model, Landuyt et al evaluated the effect of a single intraperitoneal injection of fosbretabulin (25 mg/kg) on tumor growth.21 For very large tumors, the differential growth delay was 17.6-fold stronger than what was measured for very small tumors.21 Using digital subtraction angiography and microsurgical cannulation of a major tumor draining vessel, the investigators discovered that tumor growth delay was related to extensive breakdown of existing tumor vasculature within 3–6 hours of drug administration.21 In a recent exploratory analysis of a randomized phase 3 trial in patients with non-small-cell lung carcinoma treated with docetaxel with and without the VDA plinabulin, Bazhenova, et al reported a survival benefit among patients with lung lesions > 3 cm.22

The distinct physiologic targets of anti-vascular drug classes may inform the clinical ramifications. Due to their preventative action or new vessel growth, anti-angiogenic drugs may require prolonged (e.g., 30-minute infusion) and chronic administration, and are likely to be most effective in patients with asymptomatic low-volume metastatic disease.14 In contrast, VDAs, when given acutely over 10 minutes, have more immediate action and should be particularly effective against larger tumor burdens.14

Although the antivascular chemotherapy-free doublet studied in GOG-0186I did not impact survival, inability to control for post-progression therapy continues to hinder efforts to demonstrate a survival advantage in what is essentially a chemosensitive disease. Through the availability of poly (ADP ribose) polymerase inhibitors for recurrent disease23–29 and clinical trials studying immune checkpoint inhibitors30 and novel combinations31–33 the therapeutic arena continues to evolve. Setting aside broad assumptions concerning tumor biology and potential for cumulative toxicities, an emergent clinical landscape becomes gradually discernible amidst discordant populations engaged in current studies. This fragmented model can be aligned, and while specific areas are necessarily obscured by indeterminacy, we may still speculate on feasible clinical benchmarks and hypothesize on viable combinations. While careful patient selection and management of blood pressure prior to and after fosbretabulin administration is likely to mitigate cardiovascular manifestations,34 these effects may also be circumvented with the nanoparticle drug delivery vehicles for tubulin inhibitors currently in development.35

Although the initial results of GOG-186I demonstrating a PFS benefit attributed to the experimental regimen were considered binding, there was an interest in re-evaluating the clinical endpoints with extended follow-up. It should be recognized, however, that the current observations are based on a post-hoc analysis of the study. Additional limitations include the use of dichotomized variables for tumor size. Although our rationale to use the median tumor size was justified to prevent outliers to overwhelm the analyses, there is still the potential for lost information and possible underestimation of variation in outcome between patients treated on the control arm and combined regimen arm.

Our observations concerning bulky disease also warrant additional study and offer the potential to broaden the therapeutic window even further. Patients rendered suboptimally debulked may respond to regimens that include combined targeted anti-vascular therapy. Additionally, patients with platinum-resistant recurrent disease remain at high risk as a consequence of aggressive tumor biology and/or suboptimal surgery at diagnosis. This population may be more likely to have large volume (i.e., bulky) metastases that would lend itself to dual anti-vascular blockade with bevacizumab plus fosbretabulin. It remains unclear whether the poorer efficacy observed in small volume disease is a spurious finding due to the exploratory nature of this analysis or perhaps reflects lack of sufficient tumor substrate given the distinct tumor domains bevacizumab and fosbretabulin target.It is interesting that the activity of anti-angigenesis therapy (including the label for bevacizujmab in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer) appears to be predicated on measureable disease (eg., suboptimal FIGO stage III and FIGO stage IV cancer). This is consistent with the activity of bevacizumab in other tumnor types and this phenomenon may be driving the PFS and objective response rate in bulky tumors when fosbretabulin is added.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Forest Plot generated when using a model to evaluate tumor size as a continuous variable. The data was broken down into Quartiles:

Q1 (≤2.6 cm): HR 0.910; 90% CI, 0.428-1.937

Q2 (>2.6 cm to ≤5.7 cm): HR 0.479; 90% CI, 0.209-1.094

Q3 (>5.7 cm up to ≤9 cm): HR 0.511, 90% CI, 0.221-1.182

Q4 (> 9 cm): HR 0.638; 90% CI, 0.297-1.375

Based on this analysis it appears that patients benefit with larger tumor size with only the 1st quartile having less effectiveness. All the upper bounds are above 1 so nothing is “significant” when studying tumor size as a continuous variable and this is expected. The sample sizes continue to get smaller with the finer grained analysis and therefore power gets considerable smaller leading to insignificant results.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Tumor vascular disrupting agents represent a novel anti-vascular strategy

Combined vascular disrupting agent plus anti-angiogenesis therapy may have activity in bulky, recurrent ovarian carcinoma

The combination appears to be tolerable in the subpopulations studied.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to NRG Oncology (1 U10 CA180822) and NRG Operations (U10CA180868) and UG1CA189867 (NCORP).

The following NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions participated in this study: University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Women and Infants Hospital, Washington University School of Medicine, University of California Medical Center at Irvine-Orange Campus, Saint Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Indiana University Hospital/Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center, Colorado Cancer Research Program NCORP, Duke University Medical Center, University of California at Los Angeles Health System, Delaware Christiana Care CCOP, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Women’s Cancer Center of Nevada, University of Chicago, The Hospital of Central Connecticut, Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Mississippi Medical Center, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care, Yale University, Georgia Center for Oncology Research and Education (CORE), Saint Vincent Hospital, Greenville Health System Cancer Institute/Greenville CCOP and Rush University Medical Center.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Krishnansu Tewari is a Steering Committee member for FOCUS trial with honorarium of $1000.

Dr. Coleman reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from Merck, personal fees from Tesaro, personal fees from Medivation, grants and personal fees from Clovis, personal fees from Gamamab, grants and personal fees from Genmab, grants and personal fees from Roche/Genentech, grants and personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Agenus, personal fees from Regeneron, personal fees from OncoQuest, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Aghajanian reports personal fees from Tesaro, personal fees from Immunogen, grants and personal fees from Clovis, personal fees from Mateon Therapeutics, grants from Genentech, grants from AbbVie, grants from Astra Zeneca, grants from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from Eisai/Merck, personal fees from Mersana Therapeutics, personal fees from Roche, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Mannel reports grants from The GOG/NRG NCI cooperative group system, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Tesaro, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Powell reports personal fees from Tesaro, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Roche/ Genentech, personal fees from Clovis Oncology, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, personal fees from Eisai, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Randall reports grants from Gynecologic Oncology Group, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Genentech/Roche, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Monk reports personal fees from Abbvie, personal fees from Advaxis, personal fees from Agenus, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Aravive, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Asymmetric Therapeutics, personal fees from Boston Biomedical, personal fees from ChemoCare, personal fees from ChemoID, personal fees from Circulogene, personal fees from Clovis, personal fees from Conjupro, personal fees from Easai, personal fees from Geistlich, personal fees from Genmab/Seattle Genetics, personal fees from GOG Foundation, personal fees from ImmunoGen, personal fees from Immunomedics, personal fees from Incyte, personal fees from Janssen/Johnson&Johnson, personal fees from Laekna Health Care, personal fees from Mateon (formally Oxigene), personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Mersana, personal fees from Myriad, personal fees from Nucana, personal fees from Oncomed, personal fees from Oncoquest, personal fees from Oncosec, personal fees from Perthera, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Precision Oncology, personal fees from Puma, personal fees from Regeneron, personal fees from Roche/Genentech, personal fees from Samumed, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Tesaro/GSK, personal fees from VBL, personal fees from Vigeo, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

All other co-authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eskander RN, Tewari KS. Incorporation of anti-angiogenesis therapy in the management of advanced ovarian carcinoma – Mechanistics, review of phase III randomized clinical trials, and regulatory implications. Gynecol Oncol 2014;1132:496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer, et al. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2484–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.du Bois A, Kristensen G, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Standard first-line chemotherapy with or without nintedanib for advanced ovarian cancer (AGO-OVAR 12): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.du Bois A, Floquet A, Kim JW, et al. Incorporation of pazopanib in maintenance therapy of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2039–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman RL, Brady MF, Herzog TJ, et al. A phase III randomized controlled clinical trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or in combination with bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab and secondary cytoreductive surgery in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian, peritoneal primary and fallopian tube cancer (Gynecologic Oncology Group 0213). Gynecol Oncol 2015;137:3–4 (abstr #3). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledermann JA, Embleton AC, Raja F, et al. Cediranib in patients with relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (ICON 6): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;387:1066–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monk BJ, Poveda A, Vergote I, et al. Anti-angiopoietin therapy with trebananib for recurrent ovarian cancer (TRINOVA-1): a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo- controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tewari KS, Burger RA, Enserro D, et al. Final overall survival of a randomized trial of bevacizumab for primary treatment of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019/37:2317–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siemann DW, Bibby MC, Dark GG, et al. Differentiation and definition of vascular-targeted therapies. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11(2 Pt 1): 416–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathan P, Zweifel M, Padhani AR, et al. Phase I trial of combretastatin A4 phosphate (CA4P) in combination with bevacizumab in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:3428–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monk BJ, Sill MW, Walker JL, et al. Randomized phase II evaluation of bevacizumab versus bevacizumab plus CA4P in recurrent ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal carcinoma: An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2279–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantel N Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep 1966;50:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc [B] 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inglis DJ, Lavranos TC, Beaumont DM, et al. The vascular disrupting agent BNC105 potentiates the efficacy of VEGF and mTOR inhibitors in renal and breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2014;15:1552–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siemann DW, Shi W. Dual targeting of tumor vasculature: combining Avastin and vascular disrupting agents (CA4P or OXi4503). Anticancer Res 2008;28:2027–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen L, Fifis T, Christophi C. Vascular disruptive agent OXi4503 and anti-angiogenic agent sunitinib combination treatment prolong survival of mice with CRC liver metastasis. BMC Cancer 2016;16:533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landuyt W, Verdoes O, Darius DO, et al. Vascular targeting of solid tumours: a major ‘inverse’ volume-response relationship following combrestatin A-4 phosphate treatment of rat rhabdomyosarcomas. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36:1833–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bazhenova L, Lee G, Mikrut W, Huang L. Randomized phase 3 trial of docetaxel plus plinabulin compared to docetaxel in advanced non-small cell lung cancer with at least 1 large lung lesion. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:S555. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1382–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA 1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:244–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt AM, et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med Epub 2016. October 7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kristeleit R, Shapiro GI, Burris HA et al. A phase I-II study of the oral PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with germline BRCA 1/2-mutated ovarian carcinoma or other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4095–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, et al. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international, multicenter, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA 1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1274–84.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL 3): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:1949–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore KN, Secord AA, Geller MA, et al. Niraparib monotherapy for late-line treatment of ovarian cancer (QUADRA): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:636–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaillard SL, Secord AA, Monk BJ. The role of immune checkpoint inhibition in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract 2016;3:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedlander M, Meniawy T, Markman B, et al. A phase 1b study of the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody BGB-A317 (A317) in combination with the PARP inhibitor BGB-290 (290) in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(suppl; abstr 3013). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konstantinopoulos PA, Munster P, Forero-Torez A, et al. TOPACIO: Preliminary activity and safety in patients (pts) with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROC) in a phase 1/2 study of niraparib in combination with pembrolizumab. 2018. Annual Meeting, Society of Gynecologic Oncology, New Orleans, LA, LBA-3 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drew Y, de Jonge M, Hong SH, et al. An open-label, phase II basket study of olaparib and durvalumab (MEDIOLA): Results in germline BRCA-mutated (gBRCAm) platinum-sensitive relapsed (PSR) ovarian cancer (OC). 2018. Annual Meeting, Society of Gynecologic Oncology, New Orleans, LA, LBA-4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grisham R, Ky B, Tewari KS, et al. Clinical trial experience with CA4P anticancer therapy: focus on efficacy, cardiovascular adverse events, and hypertension management. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract 2018;5:1 doi: 10.1186/s40661-017-0058-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee S, Hwang D-J, Li W, Miller DD. Current advances of tubulin inhibitors in nanoparticle drug delivery and vascular disruption/angiogenesis. Molecules 2016;21:E1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Forest Plot generated when using a model to evaluate tumor size as a continuous variable. The data was broken down into Quartiles:

Q1 (≤2.6 cm): HR 0.910; 90% CI, 0.428-1.937

Q2 (>2.6 cm to ≤5.7 cm): HR 0.479; 90% CI, 0.209-1.094

Q3 (>5.7 cm up to ≤9 cm): HR 0.511, 90% CI, 0.221-1.182

Q4 (> 9 cm): HR 0.638; 90% CI, 0.297-1.375

Based on this analysis it appears that patients benefit with larger tumor size with only the 1st quartile having less effectiveness. All the upper bounds are above 1 so nothing is “significant” when studying tumor size as a continuous variable and this is expected. The sample sizes continue to get smaller with the finer grained analysis and therefore power gets considerable smaller leading to insignificant results.