Abstract

The incidence, severity, and mortality of ongoing coronavirus infectious disease 19 (COVID-19) is greater in men compared with women, but the underlying factors contributing to this sex difference are still being explored. In the current study, using primary isolated human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells from normal males versus females as a model, we explored the effect of estrogen versus testosterone in modulating the expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a cell entry point for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Using confocal imaging, we found that ACE2 is expressed in human ASM. Furthermore, Western analysis of ASM cell lysates showed significantly lower ACE2 expression in females compared with males at baseline. In addition, ASM cells exposed to estrogen and testosterone for 24 h showed that testosterone significantly upregulates ACE2 expression in both males and females, whereas estrogen downregulates ACE2, albeit not significant compared with vehicle. These intrinsic and sex steroids induced differences may help explain sex differences in COVID-19.

Keywords: airway smooth muscle, estrogen, SARS-CoV-2, sex difference, testosterone

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the recently discovered severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) strain, a member of the family of coronaviruses that caused ailments such as the common cold to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and SARS-CoV-induced acute respiratory syndrome (2). The lung is a critical target organ in COVID-19 with the virus amplifying itself using host cells and eventually destroying lung structural cells leading to respiratory distress and its sequelae (2). The main point of cellular entry for SARS-CoV-2 is via SARS-CoV-2 spike protein 1 (S1)-bound angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) (25, 40, 41). Thus, mechanisms that regulate cellular ACE2 expression and functionality have the potential to influence the progression and outcomes of COVID-19.

Emerging clinical and epidemiological evidence suggests sex/gender disparities in the incidence and severity of COVID-19 and its associated mortality (8, 10, 14, 19, 20, 23, 29, 34, 35). While the incidence is influenced by many underlying factors, severity and mortality are clearly higher in males compared with females (1), which may reflect intrinsic sex differences or more intriguingly a potential role of sex steroids in the pathophysiology of COVID-19. Accumulating evidence suggests that sex steroid levels are altered in COVID-19 patients (13, 26) but their functional significance is not clear. Here, sex steroid effects on structural cells are likely important in the context of chronic sequelae of COVID-19 leading to chronic lung disease. The relevance of these cell types lies in the potential for SARS-CoV-2 to target and damage epithelial layers with subsequent influences on underlying mesenchymal cells [airway smooth muscle (ASM), fibroblasts], leading to altered airway reactivity, inflammation, and fibrosis towards long-term sequelae. A recent study in normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells reported that estrogen downregulates ACE2 mRNA (36). However, to date, no studies have explored ACE2 in ASM cells, or the influence of sex steroids in the context of COVID-19 pathophysiology.

Our hypothesis is that sex steroids such as estrogen and testosterone influence airway ACE2 expression, thereby contributing to the observed sex differences in COVID-19. In this report, using human ASM from males versus females, we show that 1) ACE2 is expressed in human ASM; 2) ACE2 has lower baseline expression in ASM of females compared with males; and 3) estrogen downregulates ACE2 expression, whereas testosterone upregulates ACE2 in human ASM cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemical and reagents.

Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS), Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with F-12 (DMEM/F12), trypsin EDTA and antibiotic-antimycotic were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was procured from Millipore-Sigma (Burlington, MA). 17β-Estradiol (E2) and testosterone (Tes) were procured from Tocris (Bristol, UK). Anti-ACE2 antibody (cat no. sc-390851) was procured from Santacruz Biotech (cat no. sc-390851, Dallas, TX) and Novus Biologicals (cat no. NBP2-67692, Colorado). Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (cat no. G043) was obtained from Applied Biological Materials (Richmond, BC, Canada).

Tissue and cells.

Acquisition of human lung samples and the isolation and culturing of human ASM cells have been previously described (5, 6, 22, 28, 30, 32). Briefly, third- to sixth-generation human bronchi were obtained from lung specimens incidental to patient thoracic surgeries at Mayo Clinic (focal, noninfectious indications; typically lobectomies, rarely pneumonectomies). Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of lung tissue were used for immunofluorescence studies. ASM cells were enzymatically dissociated and maintained under standard conditions of 37°C (5% CO2, 95% air) and serum deprived for 24 h before experimentation. The initial review of patient histories with complete de-identification of samples for storage and subsequent usage was approved by Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained. We used ASM samples from both males and females and limited the culturing to <5 passages to conserve smooth muscle phenotype.

Immunofluorescence.

Standard techniques were applied to 5 μm thick lung sections. Briefly, sections were baked, processed for antigen retrieval with citrate buffer and rehydrated, permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, blocked with 10% goat serum, and exposed to antibodies against ACE2 and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Secondary antibodies were AlexaFluor-488 for ACE2 and AlexaFluor-555 for α-SMA, respectively, with DAPI counterstain for nuclei. Super-resolution Z-stack images were captured using a Zeiss confocal microscope.

Cell treatments.

Serum-deprived human ASM cells were exposed to vehicle, E2 [1 nM (5, 7)], and Tes (10 nM (22),) in DMEM/F12 (FBS free) for 24 h followed by protein collection for Western analyses (4, 5, 22).

Western analysis.

Previously described standard techniques were used (4, 5, 22). Total protein content was measured using DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad) and a minimum of 25 µg equivalent protein from each group was loaded in 4–15% gradient gels (Criterion Gel System; Bio-Rad), followed by transfer to 0.22 µm PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Turbo), blocking with 5% BSA, and overnight exposure to ACE2 (Santacruz Biotech) and β-actin primary antibodies. Bands were detected on Li-Cor Odyssey CLx system using LiCOR near-red conjugated anti-mouse-800 secondary antibodies. Densitometric analysis was performed using Image Studio software. The data are represented as ACE2/β-actin expression.

Statistical analysis.

For each group, a minimum of 4–12 independent patient samples with a minimum of two repeats for each experiment were done. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test as applicable using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data are expressed as minimum to maximum with center line depicting mean and statistical significance tested at P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

ACE2 expression in human lung tissue.

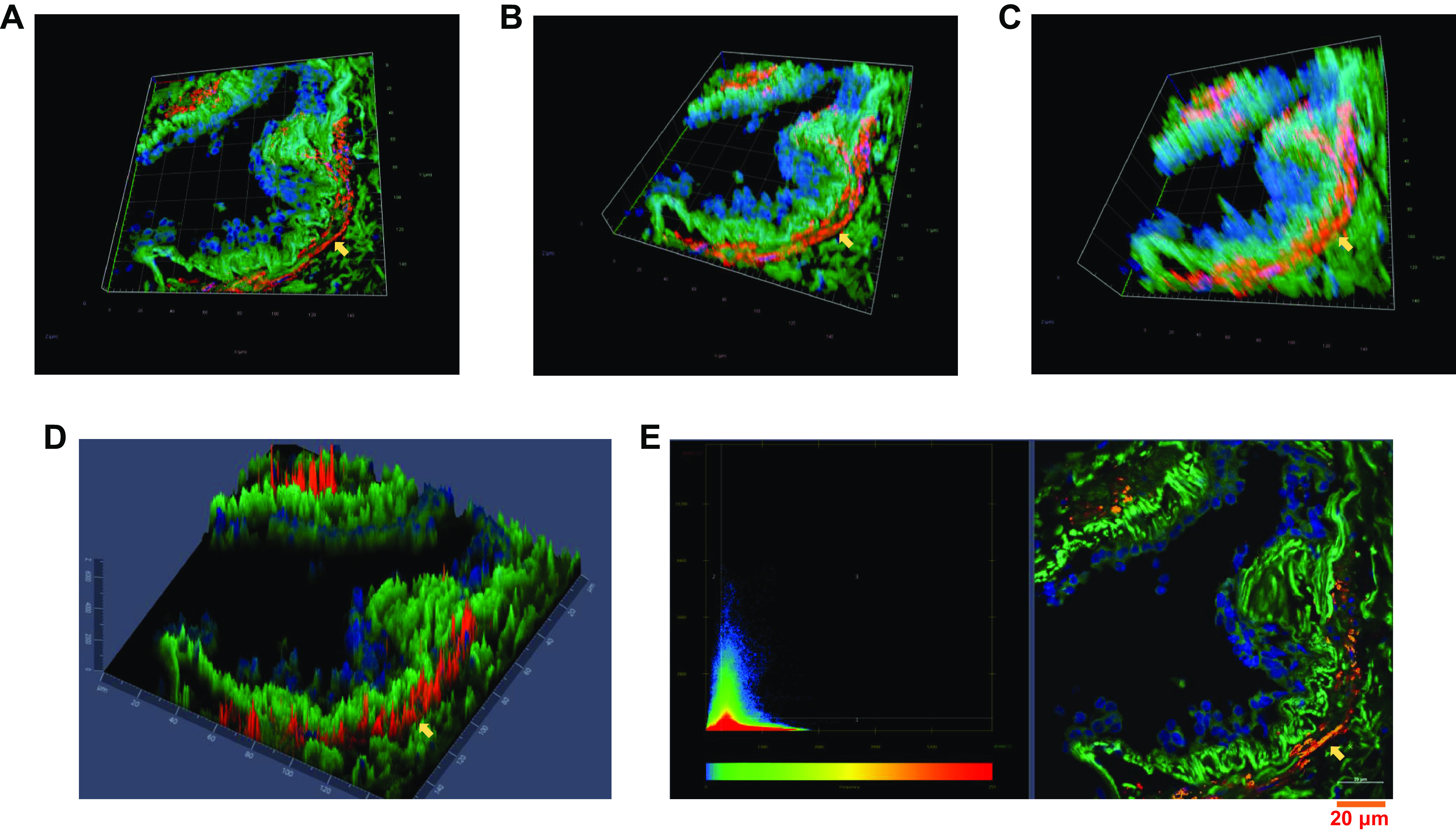

In human lung sections, ACE2 was found to be expressed across different lung cell types as shown in Z-stacked three-dimensional immunofluorescence images (Fig. 1, A, B, C, and D). We found ACE2 to be substantially colocalized with α-SMA (Fig. 1E), indicating that human ASM expresses ACE2.

Fig. 1.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is expressed in human airway tissue as indicated by immunofluorescence study. Panels showing various angles of three-dimensional (3D) Z-stack images (A, B, and C) and 2.5D image showing intensity of each fluorophore in independent pixels (D). Colocalization of ACE2 (green, AF-488) in airway smooth muscle (ASM) using α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, red, AF-555) as an ASM-specific marker, where colocalization can be seen as yellow pixels in the scatterplot (E). DAPI was used to stain nucleus (blue). Yellow arrow indicates ACE2 expression in ASM. Representative images of n = 5 independent patient samples.

ACE2 expression with respect to sex.

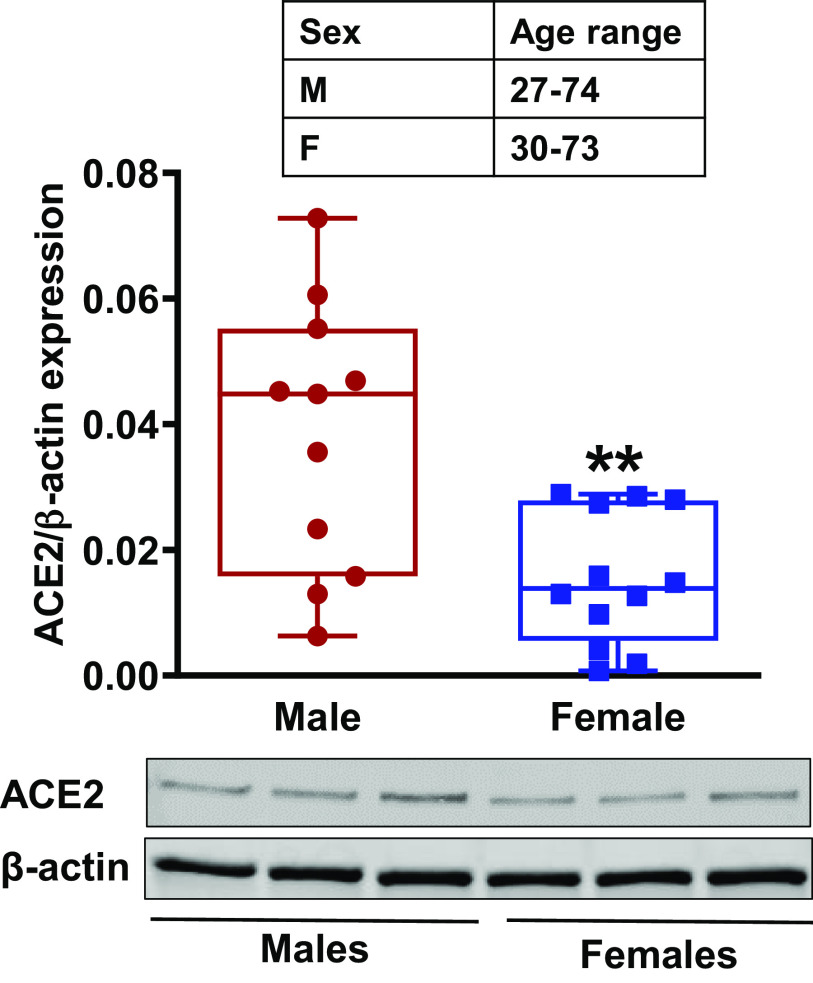

Western analysis of primary human ASM cell lysates from normal males and females indicated a significantly (P < 0.01) lower baseline expression of ACE2 in females compared with males (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Sex/gender differences in angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in primary human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells from males and females. Data represented as minimum to maximum of n = 12 for females and n = 11 males and analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t test. **P < 0.01 versus males.

Effect of sex steroids on ASM ACE2 expression.

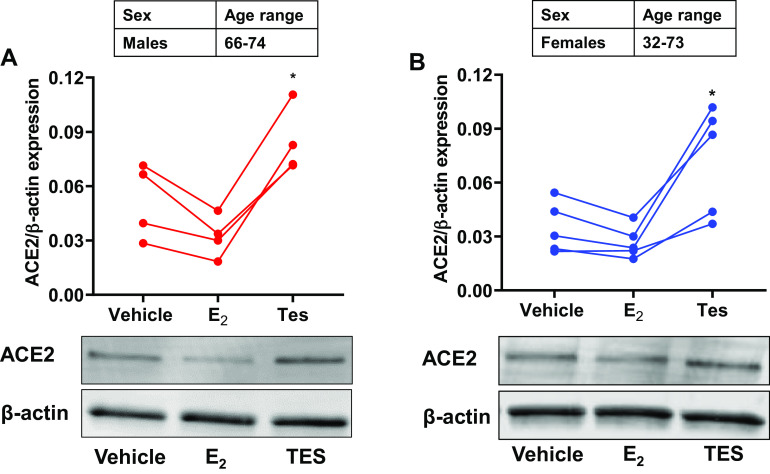

In lysates of human ASM cells exposed to vehicle, E2 or Tes, we found that E2 exposure resulted in slightly downregulated ACE2 expression in both males and females, although this was not statistically significant. Interestingly, Tes exposed human ASM cells from males and females showed significantly upregulated (P < 0.05 for males and females) ACE2 expression compared with respective vehicles (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of sex-steroids, estrogen (E2, 1 nM for 24 h) and testosterone (Tes, 10 nM for 24 h) on angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in nonasthmatic male (A) and female (B) human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells. Data represented as line plots for n = 4 males and n = 5 females and analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05 versus vehicle.

DISCUSSION

As the global death toll due to the novel coronavirus mounts, there is increasing evidence that the incidence and severity of COVID-19 and associated mortality are all greater in men compared with women. Whether these clinical observations reflect intrinsic sex differences in organ-level or whole-body responsiveness to the virus (potentially complicated by comorbidities) or whether sex steroids play a modulatory role is not clear. Given emerging evidence for differences in sex steroid levels in COVID-19 patients (8, 10, 14, 19, 20, 23, 29, 34, 35), we explored whether sex steroids (estrogen and testosterone) modulate specific aspects of SARS-CoV-2 functionality, focusing on ACE2 expression in the lung, the critical target organ of the virus. We focused on the airway, appreciating the fact that following initial infection, progressive involvement of structural cells of the airway can contribute to long-term sequelae of viral infection. While the epithelium is the primary entry point for SARS-CoV-2, following initial infection and cellular damage, the underlying ASM is likely the subsequent target and thus needs to be explored. While some studies have reported the effect of estrogen on ACE2 expression in other cell types (36), there have not been any studies in the airway, or on the role of estrogen and testosterone in regulating ASM ACE2 expression.

Multiple groups, including our own, have shown a role for sex steroids, especially estrogen (3–5, 12, 15–17, 21, 22, 31, 33, 37–39) and testosterone (11, 18, 22, 24, 27) in regulating the pathophysiology of lung diseases such as asthma or COPD as well as the known sex differences in these conditions (9). In this regard, sex steroids can differentially influence the expression and functionality of multiple signaling pathways in lung cells including ASM, contributing to altered airway reactivity and remodeling. In this novel study, we report that ACE2 is expressed in human ASM. Furthermore, our Western data from cell lysates of female patients show downregulated baseline ACE2 expression compared with males, which may reflect elevated circulating estradiol concentrations in females. Our data in ASM are also consistent with the recent report of lower baseline ACE2 mRNA in airway epithelial cells and the blunting effect of estrogen at supraphysiological concentration (36). Perhaps more interestingly, Tes exposure significantly upregulated ACE2 expression in human ASM cells. Here, it is important to note that E2 and Tes concentrations used in our study are physiological (4, 5, 7, 22, 38, 39). Furthermore, we have previously reported that both male and female human ASM expresses estrogen receptor isoforms (alpha and beta) as well as the androgen receptor (6, 22). Thus, while there is an understandable focus on the “protective” role of estrogens, it is possible that circulating Tes in males in fact contributes to elevated ACE2 expression, thereby increasing susceptibility for SARS-CoV-2. What is not known is the mechanisms by which Tes could upregulate ACE2, and whether such effects also occur in other cell types, particularly epithelium. Conversely, the mechanisms underlying an inhibitory role for estradiol may be important to understand towards approaches to blunt ACE2 expression and reduce viral infectivity.

In conclusion, our novel findings suggest a differential role for male versus female sex steroids in a key aspect of COVID-19 pathophysiology: ACE2 expression in ASM cells. Although not a focus of this report, it may be worthwhile to explore whether factors such as age, and local sex steroid metabolism further influence differential ACE2 expression based on sex. Our data set the stage to understand whether sex steroids also differentially influence downstream aspects of SARS-CoV-2 functionality in terms of viral entry and intracellular expansion.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL123494, R01-HL123494-02S1, R01-HL146705 (to V.S), R01‐HL088029 (to Y.S.P.), and R01‐HL142061 (to C.M.P. and Y.S.P.). The authors also acknowledge the Confocal Microscopy Core Facility under the Dakota Cancer Collaborative on Translational Activity (supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant U54GM128729).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.S.R.K., N.S.A., C.M.P., Y.S.P., and V.S. conceived and designed research; R.S.R.K., N.A.B., and N.S.A. performed experiments; R.S.R.K., N.A.B., and N.S.A. analyzed data; R.S.R.K., N.A.B., N.S.A. and V.S. interpreted results of experiments; R.S.R.K., N.A.B., and N.S.A. prepared figures; R.S.R.K., N.A.B., and N.S.A. drafted manuscript; C.M.P., Y.S.P., and V.S. edited and revised manuscript; R.S.R.K., N.A.B., N.S.A., C.M.P., Y.S.P., and V.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Daily updates of totals by week and state (Online). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm [24 July 2020].

- 2.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (Online). https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses [24 July 2020].

- 3.Ambhore NS, Kalidhindi RSR, Loganathan J, Sathish V. Role of differential estrogen receptor activation in airway hyperreactivity and remodeling in a murine model of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 61: 469–480, 2019. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0321OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambhore NS, Kalidhindi RSR, Pabelick CM, Hawse JR, Prakash YS, Sathish V. Differential estrogen-receptor activation regulates extracellular matrix deposition in human airway smooth muscle remodeling via NF-κB pathway. FASEB J 33: 13935–13950, 2019. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901340R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambhore NS, Katragadda R, Raju Kalidhindi RS, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Sathish V. Estrogen receptor beta signaling inhibits PDGF induced human airway smooth muscle proliferation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 476: 37–47, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aravamudan B, Goorhouse KJ, Unnikrishnan G, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Hawse JR, Prakash YS, Sathish V. Differential expression of estrogen receptor variants in response to inflammation signals in human airway smooth muscle. J Cell Physiol 232: 1754–1760, 2017. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhallamudi S, Connell J, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Sathish V. Estrogen receptors differentially regulate intracellular calcium handling in human nonasthmatic and asthmatic airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 318: L112–L124, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00206.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhopal R. Covid-19 worldwide: we need precise data by age group and sex urgently. BMJ 369: m1366, 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borkar NA, Sathish V. Sex steroids and their influence in lung disease across the lifespan Sex-Based Differences in Lung Physiology, edited by Silveyra P, Xenia T. New York: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai H. Sex difference and smoking predisposition in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med 8: e20, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30117-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbajal-García A, Reyes-García J, Casas-Hernández MF, Flores-Soto E, Díaz-Hernández V, Solís-Chagoyán H, Sommer B, Montaño LM. Testosterone augments β2 adrenergic receptor genomic transcription increasing salbutamol relaxation in airway smooth muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol 510: 110801, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cephus JY, Gandhi VD, Shah R, Brooke Davis J, Fuseini H, Yung JA, Zhang J, Kita H, Polosukhin VV, Zhou W, Newcomb DC. Estrogen receptor-α signaling increases allergen-induced IL-33 release and airway inflammation. Allergy all. 14491, 2020. doi: 10.1111/all.14491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Channappanavar R, Fett C, Mack M, Ten Eyck PP, Meyerholz DK, Perlman S. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Immunol 198: 4046–4053, 2017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maleki Dana P, Sadoughi F, Hallajzadeh J, Asemi Z, Mansournia MA, Yousefi B, Momen-Heravi M. An insight into the sex differences in COVID-19 patients: what are the possible causes? Prehosp Disaster Med 35: 438–441, 2020. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X20000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuentes N, Cabello N, Nicoleau M, Chroneos ZC, Silveyra P. Modulation of the lung inflammatory response to ozone by the estrous cycle. Physiol Rep 7: e14026, 2019. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuentes N, Nicoleau M, Cabello N, Montes D, Zomorodi N, Chroneos ZC, Silveyra P. 17β-Estradiol affects lung function and inflammation following ozone exposure in a sex-specific manner. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 317: L702–L716, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00176.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuseini H, Cephus JY, Wu P, Davis JB, Contreras DC, Gandhi VD, Rathmell JC, Newcomb DC. ERα signaling increased IL-17A production in Th17 cells by upregulating IL-23R expression, mitochondrial respiration, and proliferation. Front Immunol 10: 2740, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuseini H, Yung JA, Cephus JY, Zhang J, Goleniewska K, Polosukhin VV, Peebles RS Jr, Newcomb DC. Testosterone decreases house dust mite-induced type 2 and IL-17A-mediated airway inflammation. J Immunol 201: 1843–1854, 2018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffith DM, Sharma G, Holliday CS, Enyia OK, Valliere M, Semlow AR, Stewart EC, Blumenthal RS. Men and COVID-19: a biopsychosocial approach to understanding sex differences in mortality and recommendations for practice and policy interventions (Online). https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2020/20_0247.htmhttps://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2020/20_0247.htm, 2020. [3 August 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Jin JM, Bai P, He W, Wu F, Liu XF, Han DM, Liu S, Yang JK. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: Focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health 8: 152, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalidhindi RSR, Ambhore NS, Bhallamudi S, Loganathan J, Sathish V. Role of estrogen receptors α and β in a murine model of asthma: exacerbated airway hyperresponsiveness and remodeling in ERβ knockout mice. Front Pharmacol 10: 1499, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalidhindi RSR, Katragadda R, Beauchamp KL, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Sathish V. Androgen receptor-mediated regulation of intracellular calcium in human airway smooth muscle cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 53: 215–228, 2019. doi: 10.33594/000000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein SL, Dhakal S, Ursin RL, Deshpande S, Sandberg K, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Biological sex impacts COVID-19 outcomes. PLoS Pathog 16: e1008570, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kouloumenta V, Hatziefthimiou A, Paraskeva E, Gourgoulianis K, Molyvdas PA. Non-genomic effect of testosterone on airway smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 149: 1083–1091, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, Choe H, Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426: 450–454, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma L, Xie W, Li D, Shi L, Mao Y, Xiong Y, Zhang Y, Zhang M. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection upon male gonadal function: a single center-based study (Preprint). medRxiv 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26259. [DOI]

- 27.Montaño LM, Flores-Soto E, Reyes-García J, Díaz-Hernández V, Carbajal-García A, Campuzano-González E, Ramírez-Salinas GL, Velasco-Velázquez MA, Sommer B. Testosterone induces hyporesponsiveness by interfering with IP3 receptors in guinea pig airway smooth muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol 473: 17–30, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pabelick CM, Ay B, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Effects of volatile anesthetics on store-operated Ca2+ influx in airway smooth muscle. Anesthesiology 101: 373–380, 2004. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park MD. Sex Differences in Immune Responses in COVID-19. New York: Nature Publishing Group, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakash YS, Sathish V, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Sieck GC. Asthma and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reuptake in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L794, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00237.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sathish V, Freeman MR, Long E, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Cigarette smoke and estrogen signaling in human airway smooth muscle. Cell Physiol Biochem 36: 1101–1115, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000430282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sathish V, Leblebici F, Kip SN, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reuptake in porcine airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L787–L796, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00461.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sathish V, Martin YN, Prakash YS. Sex steroid signaling: implications for lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther 150: 94–108, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma G, Volgman AS, Michos ED. Sex differences in mortality from COVID-19 pandemic: are men vulnerable and women protected? JACC Case Rep 2: 1407–1410, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein RA. COVID-19: Risk groups, mechanistic insights and challenges. Int J Clin Pract. 2020. In press. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stelzig KE, Canepa-Escaro F, Schiliro M, Berdnikovs S, Prakash YS, Chiarella SE. Estrogen regulates the expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in differentiated airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 318: L1280–L1281, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00153.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Townsend EA, Miller VM, Prakash YS. Sex differences and sex steroids in lung health and disease. Endocr Rev 33: 1–47, 2012. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Townsend EA, Sathish V, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Estrogen effects on human airway smooth muscle involve cAMP and protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L923–L928, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00023.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Townsend EA, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Rapid effects of estrogen on intracellular Ca2+ regulation in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L521–L530, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00287.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 181: 281–292.e6, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367: 1444–1448, 2020. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]