Keywords: acute renal injury, chronic renal injury, ischemia-reperfusion injury, reactive oxygen species, small proline-rich region 2f

Abstract

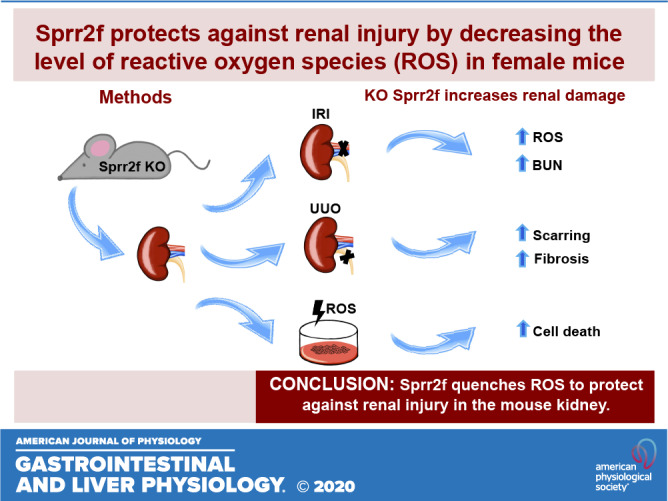

Renal injury leads to chronic kidney disease, with which women are not only more likely to be diagnosed than men but have poorer outcomes as well. We have previously shown that expression of small proline-rich region 2f (Sprr2f), a member of the small proline-rich region (Sprr) gene family, is increased several hundredfold after renal injury using a unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) mouse model. To better understand the role of Sprr2f in renal injury, we generated a Sprr2f knockout (Sprr2f-KO) mouse model using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Sprr2f-KO female mice showed greater renal damage after UUO compared with wild-type (Sprr2f-WT) animals, as evidenced by higher hydroxyproline levels and denser collagen staining, indicating a protective role of Sprr2f during renal injury. Gene expression profiling by RNA sequencing identified 162 genes whose expression levels were significantly different between day 0 and day 5 after UUO in Sprr2f-KO mice. Of the 162 genes, 121 genes were upregulated after UUO and enriched with those involved in oxidation-reduction, a phenomenon not observed in Sprr2f-WT animals, suggesting a protective role of Sprr2f in UUO through defense against oxidative damage. Consistently, bilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury resulted in higher serum blood urea nitrogen levels and higher tissue reactive oxygen species in Sprr2f-KO compared with Sprr2f-WT female mice. Moreover, cultured renal epithelial cells from Sprr2f-KO female mice showed lower viability after oxidative damage induced by menadione compared with Sprr2f-WT cells that could be rescued by supplementation with reduced glutathione, suggesting that Sprr2f induction after renal damage acts as a defense against reactive oxygen species.

INTRODUCTION

Renal fibrosis (RF), characterized by the excessive accumulation of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix, is the hallmark of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (10, 52). RF occurring after either acute or chronic kidney injuries is accompanied by glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, tubulointerstitial inflammation, and irreversible loss of parenchymal cells (10, 13). The worldwide incident rate of CKD is estimated at 9.1% and increasing (14, 26). CKD is associated with an increased risk of cardiac and all-cause mortality and costs the United States health care system an estimated $50 billion annually (26, 27, 37). Therefore, strategies for reducing or even preventing RF after renal injury are of utmost importance. Despite a host of promising experimental data, currently available strategies only ameliorate or delay the progression of CKD but do not reverse fibrosis (25, 32). Better understanding of the mechanisms underlying renal injury-induced RF and transition to CKD will provide insights into the development of novel effective therapies that improve patient outcomes.

Studies using genomic approaches have shown that renal injury from acute kidney injury (AKI) such as ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) or chronic kidney injury such as unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) generates a stereotyped response of several thousand transcripts, some of which are changed dramatically (46–48). Several of the most highly upregulated transcripts, such as lipocalin 2 and kidney injury molecule-1, encode for proteins that have been tested in a variety of clinical contexts as biomarkers of renal damage and have been shown to have important functional roles in promoting or protecting against renal damage (44, 49, 51). We and others have identified a small proline-rich region (Sprr) gene, Sprr2f, as one of the most highly upregulated transcripts after IRI- or UUO-induced renal injury (9, 40, 44, 46–48). Specifically, Sprr2f expression, which is very low at baseline, is increased by >400-fold within 24–48 h of UUO and remains elevated 28 days after obstruction with renal damage, whereas a rapid decrease of Sprr2f level was observed with 24 h of transient UUO, where there is no long-term renal compromise (47). Sprr2f is also upregulated in congenital models of urinary obstruction, and increased transcript levels can be found in the urine of children undergoing surgery for ureteropelvic junction obstruction compared with nonobstructed controls (5, 47). In addition, two recent studies by Chang-Panesso et al. (9) and Su et al. (40) demonstrated that transcript levels of Sprr2f were increased 350- and 479-fold after 24 h of IRI, respectively, and returned to baseline levels by 14 days. Moreover, Sprr2f transcript expression was detected throughout the cortex in specific tubular segments that were dilated on day 2 after IRI by in situ hybridization, which may represent localized tubular damage, whereas it was completely absent at baseline (9). However, whether Sprr2f plays a significant role in renal injury is unknown.

Sprr2f is a member of a highly homologous family of genes that are expressed in a wide variety of tissues, and individual family members show tissue-specific expression patterns (8, 33, 39). For example, Sprr2f is highly expressed in the kidney, uterus, esophagus, and bladder and is absent from other tissues where Sprr1/2 family members are expressed (15). Like Sprr2f, other family members are specifically induced in response to tissue injury. For instance, Sprr2a is induced dramatically in bile duct epithelial cells in response to ligation of the bile duct (33). In the skin, SPRR proteins have been shown to cross-link the structural proteins loricrin and involucrin to contribute to keratinization, forming a strong impermeable barrier (8, 41). Sprr genes are induced by exposure to ultraviolet radiation and the carcinogens 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbo1-13-acetate (TPA) or nitroquinoline 1 oxide (8, 41). SPRR2 proteins have also been shown to protect against reactive oxygen species (ROS) in keratinocytes (43), suggesting that Sprr2f may play a protective role in renal injury, possibly through neutralizing ROS. To test this hypothesis, we generated Sprr2f knockout (Sprr2f-KO) mice and compared the responses of these mice to IRI and UUO to wild-type (Sprr2f-WT) mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse experiments.

For all experiments, mice were 8–12 wk old and were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Animal Care Facility of Stanford University. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Stanford University (protocol no. 30864).

Generation of Sprr2f promoter Cre with ZsGreen1 reporter mice.

The Tg(Sprr2f-cre)1Dcas transgenic (Tg) mouse in an FVB background was obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA). Generation of this mouse, which has a 5.5-kb promotor sequence from the Sprr2f gene upstream of Cre, has been previously described in detail (15). Mice were genotyped to confirm the presence if the transgene using previously described methods (15). The Tg(Sprr2f-cre)1Dcas mouse was crossed with a C57/BL6 Ai6-ZsGreen1 reporter mouse purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 007906) to generate a mouse in which cells that express Sprr2f during development were permanently labeled fluorescently.

Generation of Sprr2f-KO mice.

C57/BL6 mice harboring a 1258-bp deletion spanning Sprr2f corresponding to genomic position chr3:92,365,187-92,366,442, were obtained by cytoplasmic coinjection of Cas9 mRNA and single guide (sg)RNAs into C57/BL6 zygotes using established methods (3, 38). The sgRNA sequences used to target Sprr2f exon 2, respectively, were gRNA1 5′-AGACAGGCAGTCTCGAGTTC-3′ and gRNA2 5′-GGGGAAGAGTACTTTCTATG-3′. The resulting mosaic founders were analyzed for editing at the top five algorithm-predicted off-targets, as previously described (3). Mosaic founders without off-targets were bred to WT C57/BL6 mates to generate F1 heterozygous progeny for subsequent intercrossing. Mice were backcrossed 5–10 generations to a C57/BL6 background and cross-bred to generate mice homozygous for deletion of the coding region of the Sprr2f gene.

For genotyping, DNA was prepared by digesting tissue samples at 55°C overnight in DirectPCR Mouse Tail Lysis Reagent (Viagen Biotech, Los Angeles, CA) with 25 µL of proteinase K 20 mg/mL (Invitrogen) per 1 mL of tail lysis buffer. PCRs included tail DNA (1 µL), H2O (9 µL), 10 µM (1.25 µL) primers (forward 5′-CATGGGATGAATGGTGTCTATCT-3′ and reverse 5′-GGCACTTGAATGCCTGAATATC-3′) and 12.5 µL of LongAmp Taq 2× Master Mix (New England Biolabs) to a total volume of 25 µL. PCR was carried out at 94°C for 30 s, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 65°C for 90 s, and then 65°C for 10 min. Following PCR, samples were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide (0.5 µg/mL).

Unilateral ureteral obstruction.

Surgically induced UUO was generated by applying a nontraumatic microvascular clamp on the left ureter in 8- to 12-wk-old C57/BL6 Sprr2f-KO and Sprr2-WT female mice as prevously described (46, 47). Sham-operated mice underwent laparotomy and ureteral mobilization without clamping. Left kidneys were harvested 0, 5, and 14 days after obstruction. They were bisected and one half was fixed in formalin overnight for subsequent sectioning and the other half was freezed quickly on crushed dry ice before being transfererd to a −80°C freezer for RNA isolation.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury.

C57/BL6 Sprr2f-KO and Sprr2f-WT female mice weighing 22–25 g (12 wk old) were subjected to acute kidney injury by performance of bilateral IRI. Briefly, the kidneys were exposed through a midline abdominal incision. The right and left renal pedicles were clamped sequentially by placement an atraumatic microserrafine clamp (Fine Science Tools, Cambridge, UK). Complete ischemia was indicated by color change of the kidney from red to dark purple in a few seconds. After 24 min of ischemia, the microserrafine clamps were released from each renal pedicle to allow reperfusion. Sham-operated mice were subjected to laparotomy and renal pedicle dissection without clamping of the vessels. Mice were anesthetized and euthanized by cervical dislocation 24 h after sham surgery (n = 3) or IRI (n = 10) on Sprr2f-WT mice and Sprr2f-KO mice. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and analyzed for blood urea nitrogen (BUN) by the Diagnostic Laboratory in the Animal Care Facility at Stanford University. The left kidneys were harvested and bisected and processed as described above.

RNA sequencing for gene expression.

Total RNA was isolated from fresh-frozen kidney tissues of Sprr2f-KO mice at day 0 (n = 4) and day 5 (n = 3) after UUO by using an Allprep DNA/RNA minikit (Qiagen) and analyzed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) for quality control. Total RNA was delivered to Novogene for next-generation sequencing. Briefly, libraries were constructed with a PrepX mRNA library kit (WaferGen) and sequenced to 50 bp using a TruSeq SBS kit on the Illumina Hiseq system. Raw sequencing reads were aligned to the Ensembl GRCm38.p6 reference genome using STAR (17), and gene counts were calculated using HTSeq (2). Transcript counts were normalized to the total of all transcripts detected in each sample, of which 98% corresponded to protein coding genes. Differentially expressed genes were found with a t test on log-transformed data, with statistical significance determined by the Bonferroni-Holm method (family-wise error rate < 0.05). Only protein coding genes (n = 21,933) with expression above 10 transcripts per million were used for differential expression. Gene expression data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession no. GSE153010).

Hydroxyproline assay.

Collagen content from frozen kidney tissues of Sprr2f-WT mice at day 0 (n = 2) and day 14 (n = 11) and of Sprr2f-KO mice at day 0 (n = 2) and day 14 (n = 12) after UUO was determined by measuring hydroxyproline using a modified assay based on hydrochloric acid (HCl) in Ehrlich's solution (12). Briefly, kidney tissues were homogenized in 1 mL water for 30 s using a handheld homogenizer, and solid components were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid. After baking at 110°C overnight in HCl, samples were reconstituted in water, and hydroxyproline content was measured using a colorimetric chloramine T assay (Sigma).

Tissue histology.

Kidney tissues were harvested, fixed in 10% formalin overnight, and embedded in paraffin. For fluorescence imaging of the Tg(Sprr2f-cre)1Dcas × C57/BL6 Ai6-ZsGreen1 mouse kidney samples, samples were sectioned at 5 μm thickness and photographed with a Nikon E800 fluorescence microscope (excitation: 496 nm and emission: 506 nm). Adjacent sections were dewaxed and rehydrated and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For visualization of collagen in Sprr2f-WT and Sprr2f-KO mice undergoing UUO at day 0 and day 14 (n = 2 in each group), formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded 5-μm sections were dewaxed and rehydrated followed by staining with picrosirius red (Sigma).

Tissue dihydroethidium assay.

Superoxide production was assessed histologically in kidneys from Sprr2f-KO mice (n = 2) and Sprr2f-WT mice (n = 2) after IRI by measuring dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescence. Frozen kidney tissues from mice undergoing IRI were embedded in OCT compound, cryostat sectioned at 8 μm thick, thaw mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, and stored at −80°C. Samples were washed with PBS, stained with 1 mM DHE for 30 min, and then coverslipped with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlington, CA). Slides were visualized immediately with a Leica SP8 confocal fluorescent microscope (excitation: 500–530 nm and emission: 590–620 nm). Total blue and red fluorescence in each of 35 fields per section was quantified at ×40 magnification using imageJ. The degree of DHE staining was normalized to DAPI staining for each field for comparison between samples.

Isolation and culture of renal epithelial cells.

Kidneys from Sprr2f-KO and Sprr2f-WT female mice were excised, and the capsules were removed. They were then minced with scissors into pieces 2 mm3 in size and digested in 10 mL of DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 0.5 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma). The cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 30 min in an orbital shaker (200–250 rpm), gently vortexed for 30 s, and passed through a 40-μm cell strainer. Cells were resuspended in 10 mL PBS with 0.3% EDTA to stop the collagenase activity and then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 min to form a pellet. The cell pellet was resuspended in renal epithelial cell medium (RMEM; 5% FBS, 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor, 5 μg/mL insulin, 0.5 μg/mL epinephrine, 36 ng/mL hydrocortisone, 5 μg/mL transferrin, and 4 pg/mL triiodo-l-thyronine) as previously described (11). Cells were trypsinized after the third passage and used for subsequent experiments.

Menadione treatment and Cyquant cell proliferation assays.

Renal epithelial cells from Sprr2f WT mice (n = 6) and Sprr2f KO mice (n = 7) were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 20,000 cells/well in renal epithelial cell medium. After 24 h, medium was replaced with one of three conditions with quadruplicates for each condition: 1) renal epithelial cell medium as control, 2) 20 µM menadione, or 3) 20 µM menadione with 2 mM reduced glutathione. Media were removed after another 24 h, and the plates were frozen and stored at −80°C. A Cyquant Cell Proliferation Assay (Invitrogen) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the results were tabulated.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad software (version 6.0, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All data are presented as means ± SE, and statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed paired t test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sprr2f expression in genitourinary tissues.

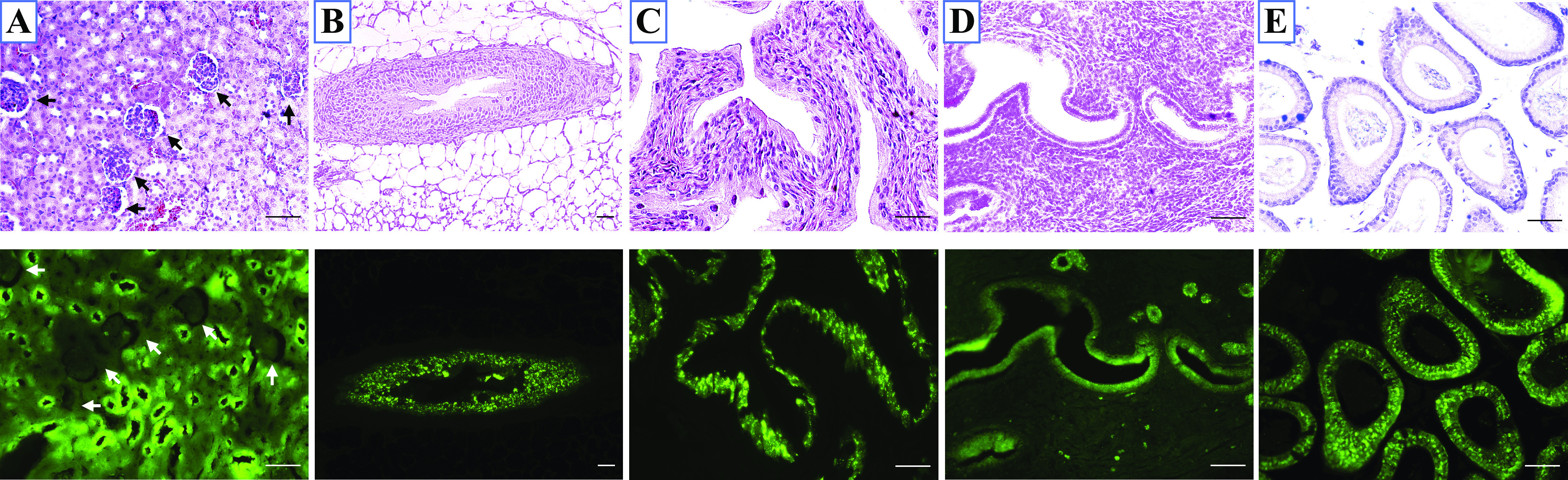

To better delineate tissue-based expression of Sprr2f in mouse genitourinary tissues, the Tg(Sprr2f-cre)1Dcas transgenic mouse was crossed with an Ai6-ZsGreen1 reporter mouse. In the resulting female and male mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the Sprr2f promoter, GFP was diffusely expressed in all cells of the nephron and the transitional epithelium of the renal pelvis but not in the glomerulus (Fig. 1A). Abundant GFP was also observed in the ureteral transitional epithelium (Fig. 1B) and bladder (Fig. 1C) in both female and male mice. Consistent with the previously reported expression pattern of Sprr2f, it was detected in the endometrium of female mice (Fig. 1D) (15). In the male mouse, the epididymal epithelium showed GFP expression (Fig. 1E), whereas the testes, all prostate lobes, seminal vesicles, and coagulating glands were entirely negative (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Small proline-rich region 2f (Sprr2f) expression in genitourinary tissues. Representative photomicrographs (magnification: ×20) of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (top) and Zs-Green fluorescent reporter show Sprr2f expression from the same section (bottom). Green fluorescent protein driven by the Sprr2f promoter was observed in all epithelial cells of the kidney (A), ureter (B), and bladder (C) in both male and female mice. It was also seen in the endometrium (D) of female mice and the epididymal epithelium of male mice (E). Scale bar = 50 μm.

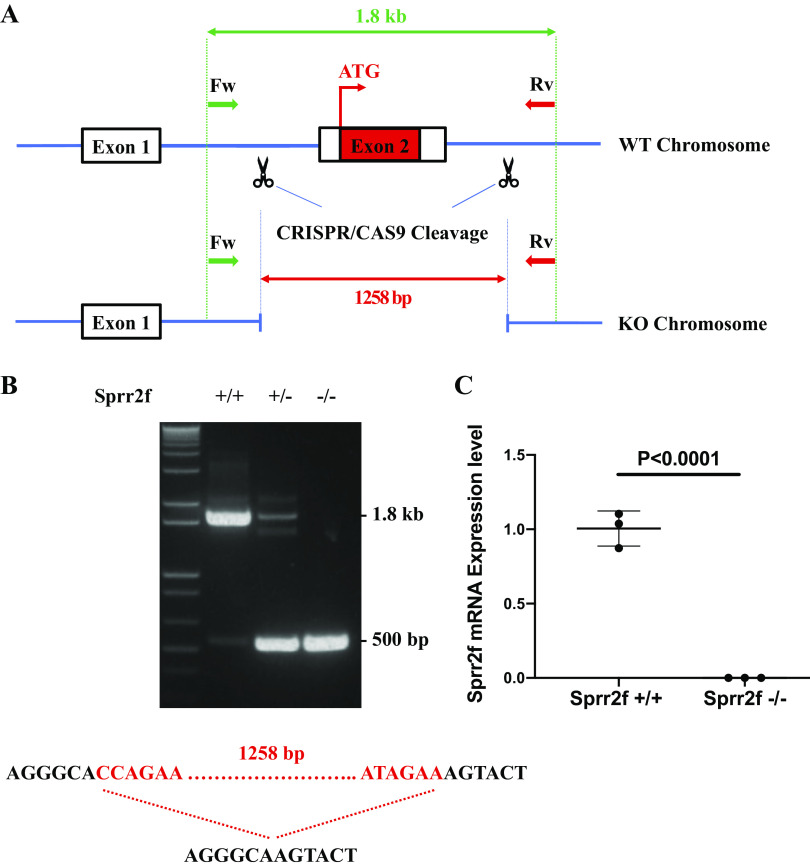

Generation of a Sprr2f-KO mouse model.

To understand the function of Sprr2f in renal injury, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to delete the second exon of the Sprr2f gene locus, generating a Sprr2f-KO mouse model. The resulting deletion of 1,258 bp encompassed the entire coding sequence of the protein SPRR2F because, like all other Sprr2 genes, Sprr2f has two exons with exon 1 noncoding (Fig. 2A). The deletion was confirmed by Sanger sequencing, and all animals were genotyped by PCR with primers that bracketed the deletion (Fig. 2B). Loss of expression of Sprr2f RNA was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2C). The mice appeared normal, with no differences in weight or growth compared with wild-type mice (data not shown). No histological abnormalities were observed across all sampled tissues (data not shown). Sprr2f-KO mice also displayed normal fertility and produced normal litter sizes with similar distributions of male and female progeny.

Fig. 2.

CRISPR/Cas9 strategy and genotyping for small proline-rich region 2f (Sprr2f) knockout (KO) mice. A: Sprr2f exon 2 was targeted for deletion (coding exons shown as solid black bars; noncoding exons shown as blue lines). Forward primer (Fw) labeled by green arrows and reverse (Rv) primer labeled by red arrows were used for validation and genotyping. B: PCR genotyping of wild-type (WT) Sprr2f+/+, heterozygous Sprr2f+/−, and homozygous KO Sprr2f−/− mice. C: Sprr2f mRNA expression in wild-type Sprr2f+/+ (n = 3) and homozygous KO Sprr2f−/− kidneys (n = 3) were validated by quantitative RT-PCR.

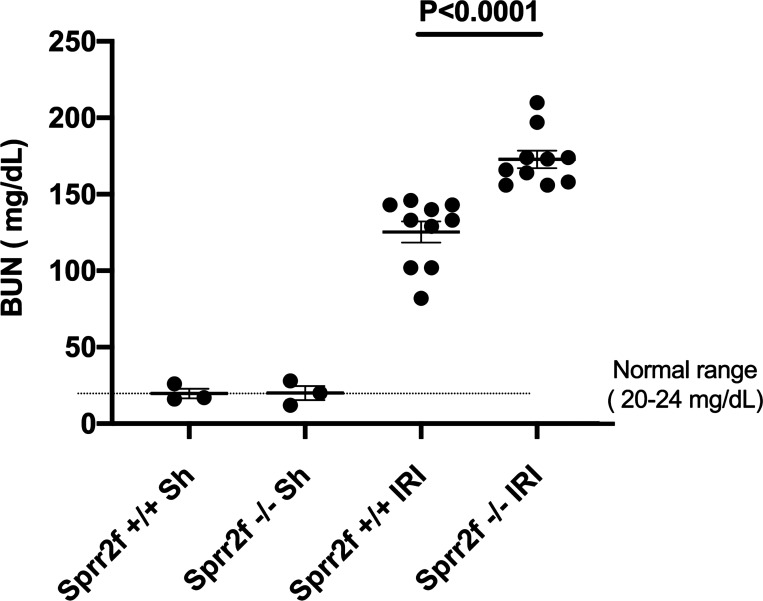

Sprr2f-KO mice show greater AKI after IRI.

Sprr2f transcript levels have been reported to increase from nearly undetectable levels to very high levels after IRI of the kidney, particularly in the cortex and corticomedullary junction (47). We evaluated whether Sprr2f protected against AKI by performing bilateral IRI on Sprr2f-WT and Sprr2f-KO mice. As shown in Fig. 3, whereas baseline plasma BUN levels were identical between Sprr2f-WT and Sprr2f-KO mice, BUN levels were dramatically increased 24 h after IRI in both Sprr2f-WT and Sprr2f-KO mice, as expected. In addition, the average BUN level in Sprr2f-KO mice, i.e., 172.8 mg/dL, was significantly higher than that in Sprr2f-WT mice, i.e., 125.3 mg/dL, representing a 37.9% increase (P < 0.0001). These results demonstrated that Sprr2f knockout confers greater renal damage in the IRI model of AKI, indicating a protective role of Sprr2f during acute AKI.

Fig. 3.

Small proline-rich region 2f knockout (Sprr2f-KO) mice display greater acute kidney injury after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were measured 24 h after sham operation (n = 3) or IRI (n = 10) in wild-type (Sprr2f-WT) and Sprr2f-KO mice. BUN levels were dramatically increased after IRI in both Sprr2f-WT and Sprr2f-KO mice. Mean BUN levels in Sprr2f-KO mice were significantly higher than in Sprr2f-WT mice.

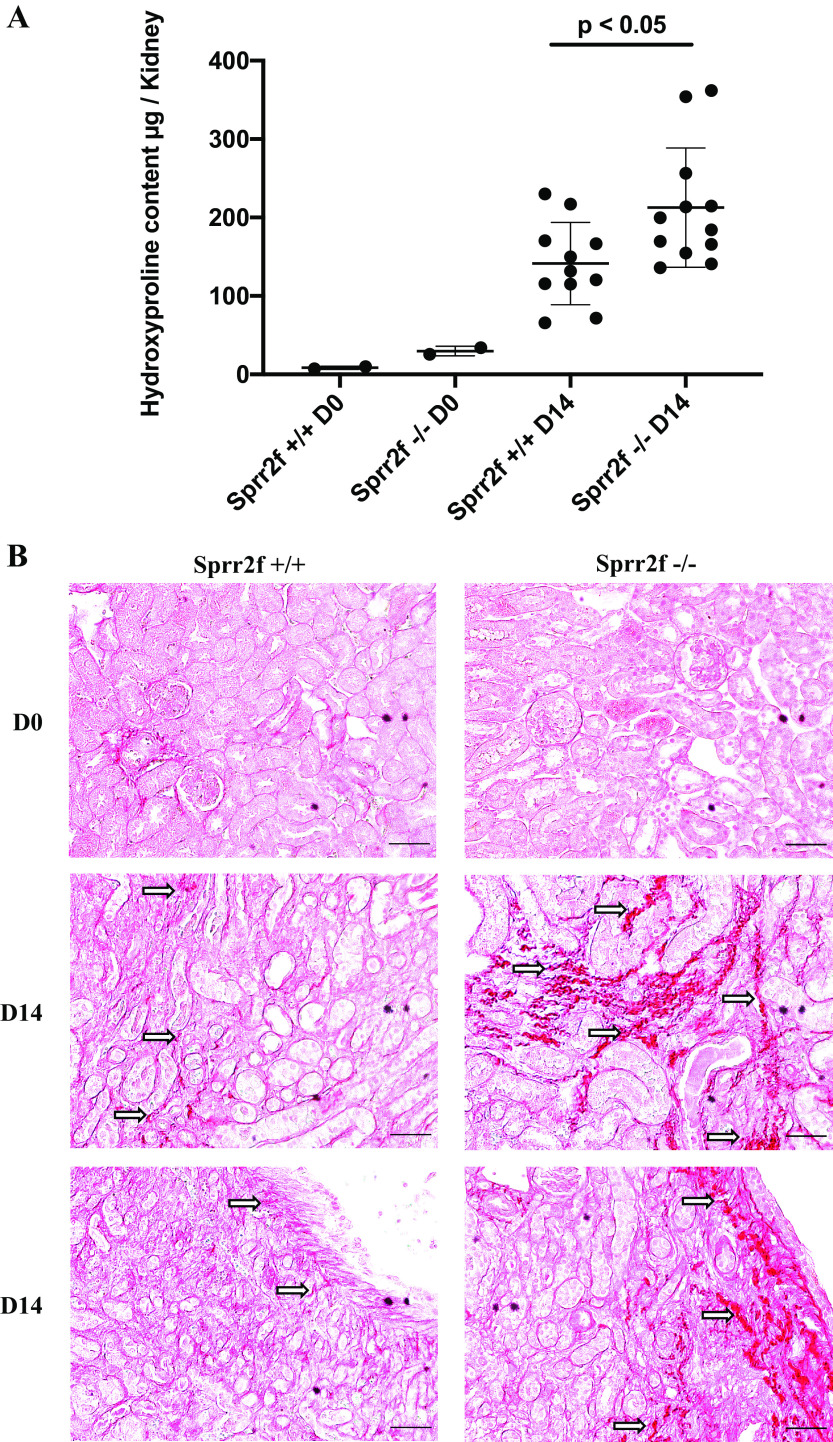

Sprr2f-KO mice show greater degree of fibrosis formation after UUO.

To determine the functional role of Sprr2f in response to chronic renal injury, we performed UUO on the left kidney of Sprr2f-KO and Sprr2f-WT female mice. Kidneys were harvested at time 0 and after 14 days of obstruction. Hydroxyproline levels as a measure of collagen content in the kidney tissues were determined to evaluate the degree of fibrosis. Hydroxyproline levels in Sprr2f-KO kidneys were significantly higher (213 vs. 148 μg/kidney, P < 0.05) compared with those in Sprr2f-WT kidneys after 14 days of UUO (Fig. 4A). Even after exclusion of the two highest outliers in the Sprr2f-KO group, hydroxyproline levels remained significantly higher in Sprr2f-KO mice compared with controls (P < 0.05). In addition, kidneys from Sprr2f-KO mice showed greater picrosirius red staining of collagen fibers compared with Sprr2f-WT mice at 14 days of UUO (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrated that Sprr2f functions to suppress RF in chronic renal injury after UUO in mice.

Fig. 4.

Unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) induces greater renal fibrosis in small proline-rich region 2f knockout (Sprr2f-KO) mice compared with wild-type (Sprr2f-WT) mice. A: no significant difference in hydroxyproline levels in kidney tissues harvested from Sprr2f-WT (n = 2) and Sprr2f-KO (n = 2) mice at day 0 (D0), whereas a significant increase in hydroxyproline content in Sprr2f-KO mice (n = 11) compared with Sprr2f-WT mice (n = 12, *P = 0.022) was observed at day 14 (D14) after UUO. B: representative images of picrosirius red staining of kidney sections of Sprr2f-WT and Sprr2f-KO mice at D0 and D14 (n = 2 in each group) after UUO (magnification: ×20). Arrows indicate collagen fibers stained in dark red. Scale bar = 50 μm.

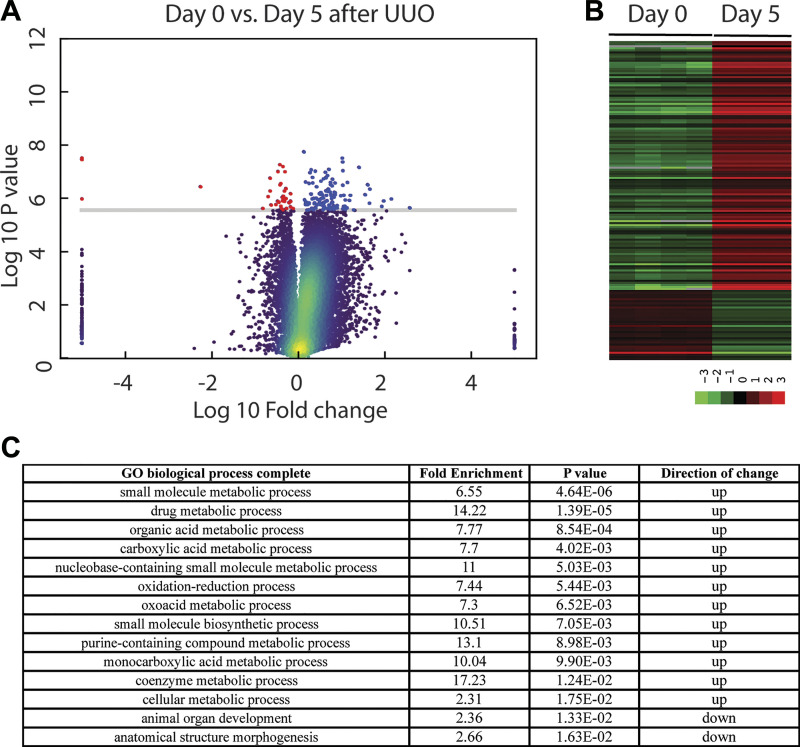

Genes involved in oxidation-reduction were upregulated in Sprr2f-KO mice after UUO.

To identify genes that are differentially expressed in Sprr2f-KO mice after UUO, we performed gene expression profiling by RNA sequencing on kidney tissues harvested from Sprr2f-KO mice at time 0 (n = 4) and after 5 days (n = 3), a time known to show dramatic changes in gene expression (47). Compared with day 0, expression levels of 162 genes were significantly changed, with 121 genes upregulated and 41 genes downregulated 5 days after obstruction (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Table S1 in the Supplemental Material, available online at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12551900.v1). As shown in the volcano plot (Fig. 5A), expression levels of these genes showed a wide range of changes, and the changes were consistent across samples in the same group depicted in the heat map (Fig. 5B). Enrichment analysis using the PANTHER classification system (29, 30) identified 12 and 2 pathways enriched in genes that are upregulated or downregulated after UUO, respectively (Fig. 5C). All of the 12 pathways enriched in the genes upregulated after UUO are related to metabolism such as drug metabolic process, consistent with a profound role of kidney as a major clearance organ of the body responsible for the elimination of many xenobiotics and prescription drugs (4). Interestingly, one of the top pathways related to metabolism enriched in genes upregulated by UUO was oxidation-reduction, suggesting a potential role of oxidative stress in renal damage after UUO in Sprr2f-KO animals. This phenotype was not observed in Sprr2f-WT animals after UUO in our previous gene expression profiling study (47), suggesting that Sprr2f function is sufficient to protect the kidney from oxidative damage after UUO in Sprr2f-WT animals.

Fig. 5.

Gene expression profiling of small proline-rich region 2f knockout (Sprr2f-KO) mice after unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). A: volcano plot of gene expression profiles of Sprr2f-KO mice at day 0 (n = 4) and day 5 (n = 3) after UUO. Genes significantly upregulated (blue dots) or downregulated (red dots) were identified by the Bonferroni-Holm method (family-wise error rate < 0.05). The y-axis is −log10; P value, representing the negative log of unadjusted P value at base 10; the x-axis is log10 fold, representing the negative log of fold change at base 10. The cutoff line on P value on the y-axis is P < 0.05. B: heatmap of genes differential expressed at day 0 and day 5 after UUO. C: pathways enriched in differentially expressed genes after UUO identified using PANTHER classification system were ranked by adjusted P value.

Sprr2f protects against ROS in vitro and in vivo.

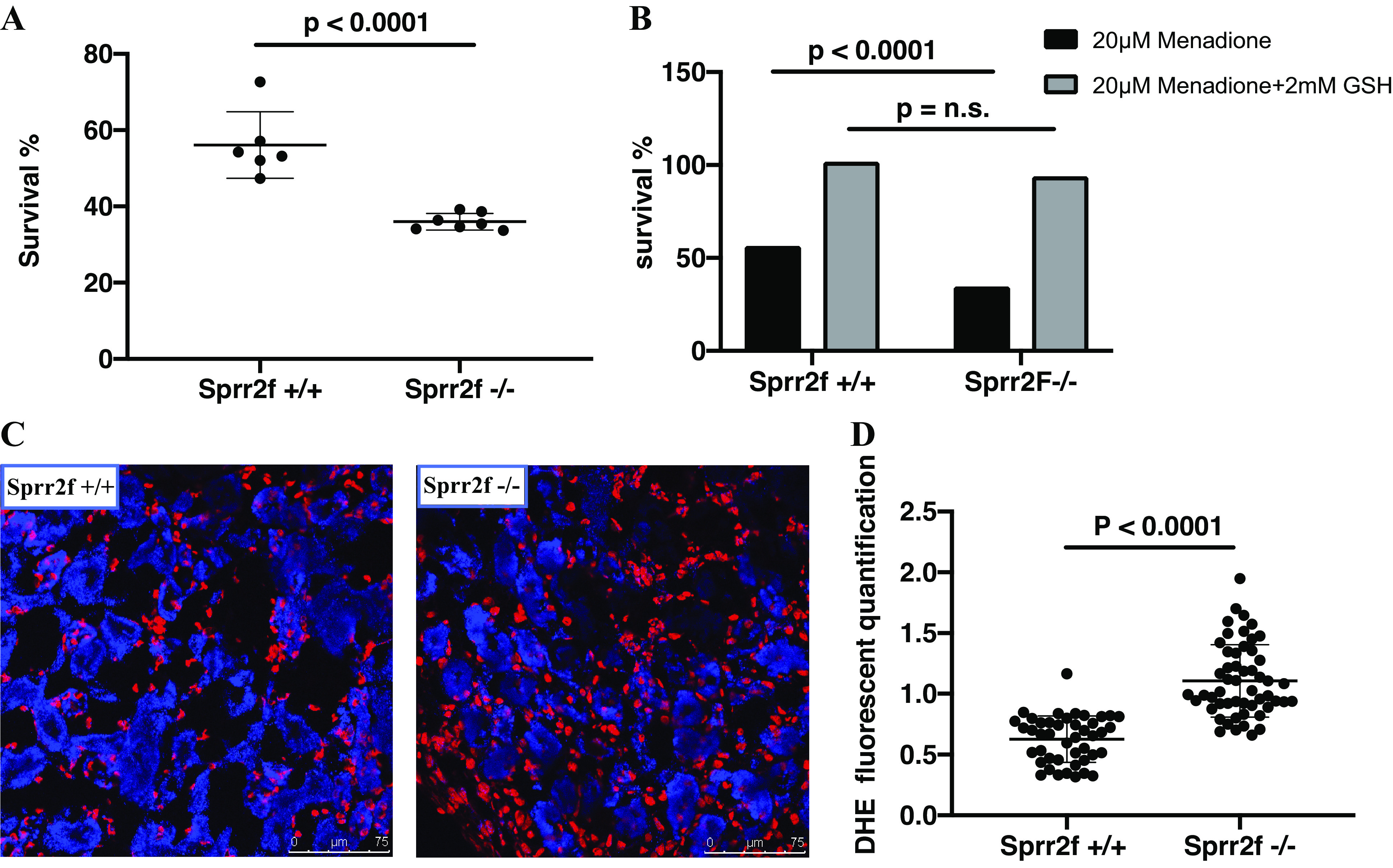

To validate the role of oxidative stress in Sprr2f-mediated protection against renal injury, we determined the effects of menadione, a mitochondrial decoupling agent known to increase intracellular ROS, on the viability of renal epithelial cells cultured from Sprr2f-KO and Sprr2f-WT mice. Cells from six (Sprr2f-WT) and seven (Sprr2f-KO) independent mice in each group were treated with 20 μM menadione, and cell viability was measured after 24 h. Sprr2f-KO cells had significantly lower rates of survival, at 36% compared with 56% of Sprr2f-WT cells (P < 0.0001; Fig. 6A). The effects of menadione on renal epithelial cell viability were rescued by glutathione (GSH), a known antioxidant capable of preventing damage to important cellular components caused by ROS. In the presence of 2 mM GSH, neither Sprr2f-WT nor Sprr2f-KO cells showed significant decreases in the percentage of surviving cells after menadione treatment (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that Sprr2f functions to protect against ROS-induced cell death in renal epithelial cells in vitro.

Fig. 6.

Small proline-rich region 2f (Sprr2f) protects against reactive oxygen species in vitro and in vivo. A: renal epithelial cells from wild-type Sprr2f+/+ mice (n = 6) and knockout (KO) Sprr2f−/− mice (n = 7) were treated for 24 h with 20 µM menadione. The percentage of live cells was determined by a Cyquant cell proliferation assay. Cells from KO Sprr2f−/− mice showed significantly lower survival compared with cells from wild-type Sprr2f+/+ mice. B: pretreatment of cells with GSH rescued renal epithelial cells from menadione-induced cell death in both wild-type Sprr2f+/+ and KO Sprr2f−/− mice. No significant difference was observed between pretreated Sprr2f+/+ and KO Sprr2f−/− mice in response to menadione. n.s., Not significant. C: representative dihydroethidium (DHE) staining in kidneys from wild-type Sprr2f+/+ (n = 2) and KO Sprr2f−/− (n = 2) 24 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). Scale bar = 75 μm. D: quantification of the DHE signal normalized against the DAPI signal showed significantly higher DHE levels in Sprr2f−/− mice (53 image fields) compared with Sprr2f+/+ mice (44 image fields).

To determine the effects of Sprr2f inactivation on ROS levels in vivo, we quantified ROS levels in kidney tissues 24 h after IRI using fluoroprobe DHE staining. The signal intensity of DHE fluorescence was measured in 35 independent fields for each kidney section using ImageJ and normalized against the nuclear DAPI fluorescence signal. DHE fluorescence was significantly higher in Sprr2f-KO mice compared with Sprr2f-WT mice (Fig. 6C), demonstrating that Sprr2f deficiency is associated with higher ROS levels in vivo. These results suggest that Sprr2f may protect ROS-induced renal injury during IRI in kidney epithelial cells in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Expression of Sprr2f was upregulated as early as a few hours after UUO and maintained at a high level at least 1 wk after UUO (47), suggesting that it is one of the early response genes to renal damage and may play an important role in regulating the process. In acute and chronic kidney injury models, loss of Sprr2f leads to increased renal damage, demonstrating that the significant induction of Sprr2f expression following kidney injury is critical to protecting against injury-induced renal loss. Absent expression of Sprr2f is associated with increased levels of ROS in the kidney following IRI, and cells lacking Sprr2f show lower viability after ROS-mediated damage that can be rescued by reduced glutathione, an antioxidant. Therefore, Sprr2f functions to dampen damage due to ROS in renal injury, likely from postinjury inflammation.

In addition to their well-described role in cross-linking proteins to generate the tough impermeable barrier characterizing skin keratinization, SPRR proteins in the skin have been shown to quench ROS, particularly due to oxidative stresses such as wound healing and ultraviolet radiation exposure (43). While this convenient marriage of functions of SPRR proteins is logical for a protein expressed constitutively in the skin, SPRR proteins, and in particular the Sprr2 family, appear to be used in diverse tissues as an inducible defense against ROS damage. The coding sequences of SPRR2 proteins are highly conserved across the gene families and are enriched free radical quenching cysteine, proline, and histidine (8, 23, 34, 43). Sprr2 gene regulatory regions, however, differ significantly across family members, providing for tissue-specific responses to injury (39). In nearly all cases, tissue-specific induction of Sprr2 genes shares a common theme of inflammation and ROS-mediated damage. For example, Sprr2a is markedly induced in biliary epithelial cells after ligation of the bile duct and in inflammatory liver disease (16, 33). It is also induced in gastrointestinal epithelial cells by a variety of infectious agents (20, 22, 31). Sprr2a and Sprr2b are induced in cardiac stress and cardiac ischemia (7, 35), while several Sprr gene family members are induced in the lung in response to viral infections, cytokine exposure, parasitic egg challenge, and smoke exposure (18, 36, 45, 50, 53). Therefore, induction of Sprr2f in the kidney reflects a general mechanism of defense that appears to be directed at modulating damage to normal tissues arising from the release of ROS.

ROS have long been known to play an important role in renal damage from diverse causes. Likewise, ROS have documented roles in mediating damage in IRI and UUO in model systems (24). Despite this, antioxidant therapies have had mixed success in treating or preventing renal damage in model systems and clinically (6, 21, 42). It is unclear why Sprr2f and selected therapeutic strategies appear to be able to prevent renal damage, but it is interesting to note that Sprr2f transcript induction measured by RNA in situ hybridization appears to be patchy in tubules throughout the kidney (9), a finding our laboratory has replicated. Since ROS have known roles in regulating regional blood flow in the kidney, it is possible that this induction regulates or is in response to local changes in perfusion (1). Regardless, Sprr2f expression, although local, appears to have widespread effects in the kidney, since global ROS appear to be increased in the Sprr2f-KO mouse. How local expression of Sprr2f mediates global changes in ROS remains to be elucidated.

It is possible that Sprr2f serves other roles in the response to renal injury. At baseline, Sprr2f is expressed at extremely low levels in the kidney; however, in the transgenic Tg(Sprr2f-cre)1Dcas/Ai6-ZsGreen1 mouse, all kidney cells were marked, implying that Sprr2f had been expressed at some time earlier in life. Exploration of GUDMAP data demonstrates that Sprr2f transcripts are expressed in the renal tubules of embryonic day 15.5 mice and in nephron progenitors in single-cell RNA sequencing data from human samples (19, 28). Thus, it is possible that Sprr2f, in addition to quenching ROS, participates in tubular cell regeneration. In cardiac cells, Sprr2b has been shown to stimulate accumulation of mouse double minute 2 and the subsequent degradation of p53, leading to proliferation of pathogenic fibroblasts (7). We observed no differences in proliferation of epithelial cells or fibroblasts cultured from Sprr2f-WT and Sprr2f-KO mouse kidneys, although we did not interrogate whether p53 levels differed in these cells. Additional work will be necessary to understand whether Sprr2f has additional roles in protecting against renal injury.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01DK101736 (to J.D.B.) and T32DK00735736 (to A.C.-Y.W.). Fluorescent imaging was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health Office of the Director Grant 1S10OD01058001A1.

DISCLAIMERS

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.H., A.W., B.W., H.Z., and J.D.B. conceived and designed research; K.H., A.W., B.W., M.H., H.Z., and J.D.B. performed experiments; K.H., A.W., B.W., M.H., H.Z., and J.D.B. analyzed data; K.H., A.W., B.W., H.Z., and J.D.B. interpreted results of experiments; K.H., M.H. and H.Z. prepared figures; K.H., M.H., H.Z., and J.D.B. drafted manuscript; K.H., M.H., H.Z., and J.D.B. edited and revised manuscript; K.H. and J.D.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. G. Edward Marti (Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Stanford University) for assistance in gene expression analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksu U, Demirci C, Ince C. The pathogenesis of acute kidney injury and the toxic triangle of oxygen, reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide. Contrib Nephrol 174: 119–128, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000329249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: 166–169, 2015. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson KR, Haeussler M, Watanabe C, Janakiraman V, Lund J, Modrusan Z, Stinson J, Bei Q, Buechler A, Yu C, Thamminana SR, Tam L, Sowick MA, Alcantar T, O’Neil N, Li J, Ta L, Lima L, Roose-Girma M, Rairdan X, Durinck S, Warming S. CRISPR off-target analysis in genetically engineered rats and mice. Nat Methods 15: 512–514, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0011-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajaj P, Chowdhury SK, Yucha R, Kelly EJ, Xiao G. Emerging kidney models to investigate metabolism, transport, and toxicity of drugs and xenobiotics. Drug Metab Dispos 46: 1692–1702, 2018. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.082958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becknell B, Carpenter AR, Allen JL, Wilhide ME, Ingraham SE, Hains DS, McHugh KM. Molecular basis of renal adaptation in a murine model of congenital obstructive nephropathy. PLoS One 8: e72762, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonventre JV, Zuk A. Ischemic acute renal failure: an inflammatory disease? Kidney Int 66: 480–485, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke RM, Lighthouse JK, Quijada P, Dirkx RA Jr, Rosenberg A, Moravec CS, Alexis JD, Small EM. Small proline-rich protein 2B drives stress-dependent p53 degradation and fibroblast proliferation in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: E3436–E3445, 2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717423115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabral A, Voskamp P, Cleton-Jansen AM, South A, Nizetic D, Backendorf C. Structural organization and regulation of the small proline-rich family of cornified envelope precursors suggest a role in adaptive barrier function. J Biol Chem 276: 19231–19237, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang-Panesso M, Kadyrov FF, Lalli M, Wu H, Ikeda S, Kefaloyianni E, Abdelmageed MM, Herrlich A, Kobayashi A, Humphreys BD. FOXM1 drives proximal tubule proliferation during repair from acute ischemic kidney injury. J Clin Invest 129: 5501–5517, 2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI125519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen PS, Li YP, Ni HF. Morphology and evaluation of renal fibrosis. Adv Exp Med Biol 1165: 17–36, 2019. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung SD, Alavi N, Livingston D, Hiller S, Taub M. Characterization of primary rabbit kidney cultures that express proximal tubule functions in a hormonally defined medium. J Cell Biol 95: 118–126, 1982. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cissell DD, Link JM, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. A modified hydroxyproline assay based on hydrochloric acid in Ehrlich’s solution accurately measures tissue collagen content. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 23: 243–250, 2017. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2017.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int 81: 442–448, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collaboration GBDCKD; GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration . Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395: 709–733, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contreras CM, Akbay EA, Gallardo TD, Haynie JM, Sharma S, Tagao O, Bardeesy N, Takahashi M, Settleman J, Wong KK, Castrillon DH. Lkb1 inactivation is sufficient to drive endometrial cancers that are aggressive yet highly responsive to mTOR inhibitor monotherapy. Dis Model Mech 3: 181–193, 2010. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demetris AJ, Specht S, Nozaki I, Lunz JG III, Stolz DB, Murase N, Wu T. Small proline-rich proteins (SPRR) function as SH3 domain ligands, increase resistance to injury and are associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cholangiocytes. J Hepatol 48: 276–288, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29: 15–21, 2013. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domachowske JB, Bonville CA, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF. Differential expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes in vivo in response to pathogenic and nonpathogenic pneumovirus infections. J Infect Dis 186: 8–14, 2002. doi: 10.1086/341082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding SD, Armit C, Armstrong J, Brennan J, Cheng Y, Haggarty B, Houghton D, Lloyd-MacGilp S, Pi X, Roochun Y, Sharghi M, Tindal C, McMahon AP, Gottesman B, Little MH, Georgas K, Aronow BJ, Potter SS, Brunskill EW, Southard-Smith EM, Mendelsohn C, Baldock RA, Davies JA, Davidson D. The GUDMAP database−an online resource for genitourinary research. Development 138: 2845–2853, 2011. doi: 10.1242/dev.063594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science 291: 881–884, 2001. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Seok YM, Jung KJ, Park KM. Reactive oxygen species/oxidative stress contributes to progression of kidney fibrosis following transient ischemic injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F461–F470, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90735.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knight PA, Pemberton AD, Robertson KA, Roy DJ, Wright SH, Miller HR. Expression profiling reveals novel innate and inflammatory responses in the jejunal epithelial compartment during infection with Trichinella spiralis. Infect Immun 72: 6076–6086, 2004. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6076-6086.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan N, Dickman MB, Becker DF. Proline modulates the intracellular redox environment and protects mammalian cells against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 44: 671–681, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu BC, Tang TT, Lv LL, Lan HY. Renal tubule injury: a driving force toward chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 93: 568–579, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F, Zhuang S. New therapies for the treatment of renal fibrosis. Adv Exp Med Biol 1165: 625–659, 2019. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv JC, Zhang LX. Prevalence and disease burden of chronic kidney disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 1165: 3–15, 2019. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCullough K, Sharma P, Ali T, Khan I, Smith WC, MacLeod A, Black C. Measuring the population burden of chronic kidney disease: a systematic literature review of the estimated prevalence of impaired kidney function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1812–1821, 2012. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMahon AP, Aronow BJ, Davidson DR, Davies JA, Gaido KW, Grimmond S, Lessard JL, Little MH, Potter SS, Wilder EL, Zhang P; GUDMAP project . GUDMAP: the genitourinary developmental molecular anatomy project. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 667–671, 2008. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Casagrande JT, Thomas PD. Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat Protoc 8: 1551–1566, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Huang X, Ebert D, Mills C, Guo X, Thomas PD. Protocol Update for large-scale genome and gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system (v.14.0). Nat Protoc 14: 703–721, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0128-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueller A, O’Rourke J, Grimm J, Guillemin K, Dixon MF, Lee A, Falkow S. Distinct gene expression profiles characterize the histopathological stages of disease in Helicobacter-induced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 1292–1297, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242741699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nastase MV, Zeng-Brouwers J, Wygrecka M, Schaefer L. Targeting renal fibrosis: mechanisms and drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 129: 295–307, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nozaki I, Lunz JG III, Specht S, Stolz DB, Taguchi K, Subbotin VM, Murase N, Demetris AJ. Small proline-rich proteins 2 are noncoordinately upregulated by IL-6/STAT3 signaling after bile duct ligation. Lab Invest 85: 109–123, 2005. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel S, Kartasova T, Segre JA. Mouse Sprr locus: a tandem array of coordinately regulated genes. Mamm Genome 14: 140–148, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-2205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pradervand S, Yasukawa H, Muller OG, Kjekshus H, Nakamura T, St Amand TR, Yajima T, Matsumura K, Duplain H, Iwatate M, Woodard S, Pedrazzini T, Ross J, Firsov D, Rossier BC, Hoshijima M, Chien KR. Small proline-rich protein 1A is a gp130 pathway- and stress-inducible cardioprotective protein. EMBO J 23: 4517–4525, 2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandler NG, Mentink-Kane MM, Cheever AW, Wynn TA. Global gene expression profiles during acute pathogen-induced pulmonary inflammation reveal divergent roles for Th1 and Th2 responses in tissue repair. J Immunol 171: 3655–3667, 2003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LY, Albertus P, Ayanian J, Balkrishnan R, Bragg-Gresham J, Cao J, Chen JL, Cope E, Dharmarajan S, Dietrich X, Eckard A, Eggers PW, Gaber C, Gillen D, Gipson D, Gu H, Hailpern SM, Hall YN, Han Y, He K, Hebert H, Helmuth M, Herman W, Heung M, Hutton D, Jacobsen SJ, Ji N, Jin Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kapke A, Katz R, Kovesdy CP, Kurtz V, Lavalee D, Li Y, Lu Y, McCullough K, Molnar MZ, Montez-Rath M, Morgenstern H, Mu Q, Mukhopadhyay P, Nallamothu B, Nguyen DV, Norris KC, O’Hare AM, Obi Y, Pearson J, Pisoni R, Plattner B, Port FK, Potukuchi P, Rao P, Ratkowiak K, Ravel V, Ray D, Rhee CM, Schaubel DE, Selewski DT, Shaw S, Shi J, Shieu M, Sim JJ, Song P, Soohoo M, Steffick D, Streja E, Tamura MK, Tentori F, Tilea A, Tong L, Turf M, Wang D, Wang M, Woodside K, Wyncott A, Xin X, Zang W, Zepel L, Zhang S, Zho H, Hirth RA, Shahinian V. US Renal Data System 2016 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 69, Suppl 1: A7–A8, 2017. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh P, Schimenti JC, Bolcun-Filas E. A mouse geneticist’s practical guide to CRISPR applications. Genetics 199: 1–15, 2015. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.169771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song HJ, Poy G, Darwiche N, Lichti U, Kuroki T, Steinert PM, Kartasova T. Mouse Sprr2 genes: a clustered family of genes showing differential expression in epithelial tissues. Genomics 55: 28–42, 1999. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su M, Hu X, Lin J, Zhang L, Sun W, Zhang J, Tian Y, Qiu W. Identification of candidate genes involved in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. DNA Cell Biol 38: 256–262, 2019. doi: 10.1089/dna.2018.4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tesfaigzi J, Carlson DM. Expression, regulation, and function of the SPR family of proteins. A review. Cell Biochem Biophys 30: 243–265, 1999. doi: 10.1007/BF02738069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomsa AM, Alexa AL, Junie ML, Rachisan AL, Ciumarnean L. Oxidative stress as a potential target in acute kidney injury. PeerJ 7: e8046, 2019. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermeij WP, Backendorf C. Skin cornification proteins provide global link between ROS detoxification and cell migration during wound healing. PLoS One 5: e11957, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viau A, El Karoui K, Laouari D, Burtin M, Nguyen C, Mori K, Pillebout E, Berger T, Mak TW, Knebelmann B, Friedlander G, Barasch J, Terzi F. Lipocalin 2 is essential for chronic kidney disease progression in mice and humans. J Clin Invest 120: 4065–4076, 2010. doi: 10.1172/JCI42004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vos JB, Datson NA, van Kampen AH, Luyf AC, Verhoosel RM, Zeeuwen PL, Olthuis D, Rabe KF, Schalkwijk J, Hiemstra PS. A molecular signature of epithelial host defense: comparative gene expression analysis of cultured bronchial epithelial cells and keratinocytes. BMC Genomics 7: 9, 2006. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu B, Brooks JD. Gene expression changes induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction in mice. J Urol 188: 1033–1041, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu B, Gong X, Kennedy WA, Brooks JD. Identification of transcripts associated with renal damage due to ureteral obstruction as candidate urinary biomarkers. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F16–F26, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00382.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu H, Lai CF, Chang-Panesso M, Humphreys BD. Proximal tubule translational profiling during kidney fibrosis reveals proinflammatory and long noncoding RNA expression patterns with sexual dimorphism. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 23–38, 2020. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019040337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang L, Brooks CR, Xiao S, Sabbisetti V, Yeung MY, Hsiao LL, Ichimura T, Kuchroo V, Bonventre JV. KIM-1-mediated phagocytosis reduces acute injury to the kidney. J Clin Invest 125: 1620–1636, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI75417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoneda K, Chang MM, Chmiel K, Chen Y, Wu R. Application of high-density DNA microarray to study smoke- and hydrogen peroxide-induced injury and repair in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 14, Suppl 3: S284–S289, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000078023.30954.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu L, Zhou L, Li Q, Li S, Luo X, Zhang C, Wu B, Brooks JD, Sun H. Elevated urinary lipocalin-2, interleukin-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 levels in children with congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. J Pediatr Urol 15: 44.e1−44.e7, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan Q, Tan RJ, Liu Y. Myofibroblast in kidney fibrosis: origin, activation, and regulation. Adv Exp Med Biol 1165: 253–283, 2019. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimmermann N, Doepker MP, Witte DP, Stringer KF, Fulkerson PC, Pope SM, Brandt EB, Mishra A, King NE, Nikolaidis NM, Wills-Karp M, Finkelman FD, Rothenberg ME. Expression and regulation of small proline-rich protein 2 in allergic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 428–435, 2005. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0269OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]