Abstract.

Delayed parasite clearance time observed in Southeast Asia provided the first evidence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to artemisinins. The ex vivo ring-stage survival assay (RSA) mimics parasite exposure to pharmacologically relevant artemisinin concentrations. Mutations in the C-terminal propeller domain of the putative kelch protein Pf3D7_1343700 (K13) are associated with artemisinin resistance. Variations in the pfmdr1 gene are associated with reduced susceptibility to the artemisinin partner drugs mefloquine (MQ) and lumefantrine (LF). To clarify the unknown landscape of artemisinin resistance in Colombia, 71 patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria were enrolled in a non-randomized observational study in three endemic localities in 2014–2015. Each patient’s parasite isolate was assessed for ex vivo RSA, K13-propeller mutations, pfmdr1 copy number, and pfmdr1 mutations at codons 86, 184, 1034, 1042, and 1246, associated with reduced susceptibility, and 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for other antimalarial drugs. Ex vivo RSAs were successful in 56% (40/71) of samples, and nine isolates showed survival rates > 1%. All isolates had wild-type K13-propeller sequences. All isolates harbored either of two pfmdr1 haplotypes, NFSDD (79.3%) and NFSDY (20.7%), and 7.1% of isolates had > 1 pfmdr1 gene. In vitro IC50 assays showed that variable proportions of isolates had decreased susceptibility to chloroquine (52.4%, > 100 nM), amodiaquine (31.2%, > 30 nM), MQ (34.3%, > 30 nM), and LF (3.2%, > 10 nM). In this study, we report ex vivo RSA and K13 data on P. falciparum isolates from Colombia. The identification of isolates with increased ex vivo RSA rates in the absence of K13-propeller mutations and no positivity at day three requires further investigation.

INTRODUCTION

The WHO reported an estimated 79,000 cases of malaria, 60% of which were caused by Plasmodium falciparum, in Colombia during 2015, when this study was performed.1 Approximately 21% of the Colombian population lives in malaria-endemic regions. Most of the cases occur in the Pacific coast region, including the states of Nariño, Cauca, Valle del Cauca, and Chocó, as well as the Amazon region in the eastern plains of the country, and rural areas alongside the Cauca River in Antioquia State.2,3 Malaria is an occupationally acquired disease in Colombia, with increased prevalence in adult populations (aged 14–64 years) and gold-mining areas.3–5 Colombia has been considered a hotspot for emergence of antimalarial resistance. Indeed, the first cases of chloroquine (CQ) and sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance in the Americas were reported in Colombia in the 1960s.6,7 Uncomplicated falciparum malaria is currently treated in Colombia with artemether–lumefantrine (AL) as first-line therapy. This combination, used in the country since 2006, has shown efficacy rates > 95% in different endemic areas.8–11 However, it is important to emphasize that circulating P. falciparum parasites have previously shown a propensity to develop drug resistance.

Ex vivo susceptibility assays are recommended as a surveillance tool to monitor the antimalarial drug responses of P. falciparum isolates.12–16 In Colombia, several ex vivo and in vitro susceptibility assays have identified circulating P. falciparum isolates resistant to CQ (> 100 nM) and decreased susceptibility to the artemisinin partner drugs AQ (> 30 nM) and MQ (> 30 nM), but highly susceptible to lumefantrine (LF, < 10 nM) and dihydroartemisinin (DHA, < 10 nM), at least in the 10 years after implementation of artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) in the same malaria-endemic areas of Colombia where this study was performed (Supplemental Table S1). One important consideration is that evaluating ex vivo P. falciparum susceptibility to artemisinin derivatives using the conventional 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) assay does not distinguish sensitive and resistant parasites; however, Witkowski et al.17 recently developed a new protocol to adequately evaluate artemisinin susceptibility.

Delayed parasite clearance time observed in Southeast Asia provided the first evidence of P. falciparum resistance to artemisinins.18,19 The ex vivo ring-stage survival assay (RSA) mimics parasite exposure to pharmacologically relevant concentrations of artemisinin that are achieved with standard treatment regimens. At present, the RSA0–3h (which uses 0- to 3-hour ring-stage parasites) is the tool of choice to monitor the in vitro responses of P. falciparum to artemisinin and its derivatives.20 The RSA0–3h discriminates artemisinin-resistant from artemisinin-sensitive parasites that show survival rates > 1% and ≤ 1%, respectively.20,21 At the molecular level, several mutations in the C-terminal propeller domain of the putative kelch protein PF3D7_1343700 are associated with artemisinin resistance.22 In addition, pfmdr1 gene amplification and mutations are associated with reduced susceptibility to MQ and LF, two ACT partner drugs formerly and currently used in Colombia.23,24 Few studies have evaluated pfkelch-propeller mutations and pfmdr1 variants of P. falciparum isolates in Colombia (Supplemental Table S1). Here, we have used recently developed methods to explore the current antimalarial susceptibility of P. falciparum isolates in patients with uncomplicated malaria in Colombia.

METHODOLOGY

Study sites and patients.

This study was conducted in three malaria-endemic sites in the states of Nariño, Choco, and Antioquia (Pacific coast and Cauca River regions). Patients diagnosed with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria at local healthcare centers were consented to voluntarily participate in the study from September 2014 to May 2015 if they met the following criteria: ≥ 7 years old, parasite density ≥ 2,000 parasites/µL, and no evidence of CQ in the urine as determined by a negative Saker-Solomons test. A sample of whole blood (9.0 mL) was drawn from each enrolled patient before treatment. All patients were treated with AL, the standard-of-care antimalarial therapy (six doses of 1.4–4 mg/kg artemether and 10–16 mg/kg LF, dosed according to age, over 3 days), and encouraged to return to clinic on day 3 of treatment for further clinical evaluation. Only the first dose of treatment was supervised. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Universidad de Antioquia. In the field, ex vivo susceptibility tests were carried out in all the samples that were P. falciparum positive by microscopy. Then, only those parasite samples confirmed to be P. falciparum by nested PCR (nPCR) were used in ex vivo and molecular association analysis.

Microscopic parasite detection and count.

Thick smears were air-dried at room temperature for 30 minutes, then dehemoglobinized with methylene blue and stained for 10 minutes with 5% Giemsa prepared in 3 mL of phosphate-buffered saline. Parasitemia was calculated by counting 200 leukocytes per slide, with a population reference value of 8,000 leukocytes/mm3. Slides were considered negative after counting 500 leukocytes or covering around 200 high-power fields. All the slides had a second blind reading by an expert technician at the reference laboratory in Medellín. A third reading was performed in case of discrepancies between the microscopic results or with the molecular test.

Ex vivo RSA.

Ex vivo RSAs were performed according to the published protocols of Witkowski et al.20,25 In brief, whole blood samples were washed twice with RPMI cell culture media and centrifuged to remove leukocytes and plasma, and then resuspended to 2% hematocrit using RPMI supplemented with 10% Albumax II. Parasite preparations were then exposed to either 700 nM DHA or 0.1% DMSO for 6 hours at 37°C under a gas mixture of 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2. After this initial incubation, DHA and DMSO were washed away twice using RPMI. Samples were then resuspended in drug-free Albumax II–supplemented RPMI and further incubated for 66 hours. After a total of 72 hours of incubation, thin-smear slides were fixed in methanol and then stained with 10% Giemsa in 0.4% NaCl following Witkowski et al.20,25 protocols. Parasitemia was calculated as the number of viable parasites counted in 10,000 red blood cells by thin-smear microscopy. Two well-trained laboratory technicians determined parasitemia independently. Ring-stage survival assay percentage was calculated as follows: (parasitemia DHA/parasitemia DMSO) × 100. All antimalarial compounds used in this study were provided by the Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN) from validated stocks.

Ex vivo IC50 assay.

A 96-well culture plate was prepared for IC50 assays by adding serial dilutions of antimalarial compounds in Albumax II–free RPMI according to standard concentrations recommended by the WWARN: 12.5 nM–1,600 nM CQ, 2.5 nM–320 nM AQ, 1 nM–128 nM LF, and 0.25 nM–32 nM DHA.26 Parasite isolates were prepared according to WWARN recommendations, adjusting the samples to 1.5% hematocrit suspension and keeping parasitemia as original in the samples, with a range of 500–17,000 parasites/µL.27 Two hundred µL of suspension were added to each well of the pre-dosed 96-well culture plate. The plate was incubated for 72 hours at 37°C under a gas mixture of 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2, and parasite growth was then determined by quantifying histidine-rich protein II by ELISA, as previously described.27–29 For quality control, P. falciparum reference strains, 3D7 (CQ-sensitive) and FCR3 (CQ-resistant), were evaluated for each batch of pre-dosed plates30; 50% inhibitory concentration calculations and analysis were performed using the WWARN in vitro analysis and reporting tool (IVART).31 Only IVART core assays were analyzed.

DNA extraction.

Whole blood DNA was extracted from dried filter paper blood spots using the QIAamp DNA Minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Nested PCR to detect parasite infection.

To confirm P. falciparum infection on day 0 and day 3 follow-up, nPCR was carried out as described,32 with minor modifications on primer annealing temperature and number of cycles. The following primers were used: Rplu6 5′-TTA AAA TTG TTG CAG TTA AAA CG-3′ and Rplu5 5′-CCT GTT GTT GCC TTA AAC TTC-3′ to amplify DNA from Plasmodium spp. in the primary PCR; and rFAL1 5′-TTA ACC TGG TTT GGG AAA ACC AA ATA TAT T-3′ and rFAL2 5′-ACA CAA TGA ACT CAA TCA TGA CTA CCC GTC-3′ to detect P. falciparum, or rVIV1 5′-CGC TTC TAG CTT AAT CCA CAT AAC TGA TAC-3′ and rVIV2 5′-ACT TCC AAG CCG AAG CAA AGA AAG TCC TTA-3′ to detect Plasmodium vivax in the nPCR. The master mix reaction contained 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dNTPs, 0.125 µM primers, and 0.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Nested PCR to amplify the entire K13-propeller domain.

We developed a novel PCR method to amplify the entire K13-propeller domain.33 The primary PCR primers (FWD) 5′-GGG AAA ATC TAA ACA ATC AAG TAA TGT G-3′ and (REV) 5′-GGG AAT CTG GTG GTA ACA GC-3′ amplified the expected 2,364-bp product under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 52°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 2.5 minutes; and final extension at 65°C for 5 minutes. The nPCR primers (FWD) 5′-TTA TAA AAT GTG CAT GAA AAT AAA TAT TAA AGA AG-3′ and (REV) 5′-CTT CTT AAG AAA TCC TTA ACR ATA CCC-3′ amplified the expected 1068-bp product under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 50°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 1 minute; and final extension at 65°C for 5 minutes. Platinum® PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as the master mix and was supplemented with 300 nM of each primer. Final volumes for primary and nPCRs were 16.5 µL (15 µL master mix + 1.5 µL DNA template) and 33 µL (30 µL master mix + 3 µL DNA template), respectively.

Sequencing the K13-propeller domain.

PCR-amplified products were sent to Macrogen (Rockville, MD) for double-stranded sequencing of the entire K13-propeller domain, using primers (FWD) 5′-TTA TAA AAT GTG CAT GAA AAT AAA TAT TAA AGA AG-3′ and (REV) 5′-GCC TTG TTG AAA GAA GCA GA3-3′ at 5 µM concentrations each. For sequence analysis, ambiguous end sequences were trimmed and assembled against the P. falciparum 3D7 K13-propeller domain using Sequencher software version 5.1 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI). By using our new set of primers, we improved the coverage of the complete C-terminal end of the K13-propeller domain.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) to estimate pfmdr1 copy number.

Pfmdr1 copy number was estimated as described,34 in a 20-μL reaction volume containing 2–8 μL DNA template, 20 μL SensiFast SYBR Green I (Bioline, Taunton, MA), and 300 nM primers (FWD) 5′-CAA GTG AGT TCA GGA ATT GGT AC-3′ and (REV) 5′-GCC TCT TCT ATA ATG GAC ATG G-3′ for the pfmdr1 gene. In the same reaction, primers (FWD) 5′-AGG ACA ATA TGG ACA CTC CGA T-3′ and (REV) 5′-TTT CAG CTA TGG CTT CAT CAA A-3′ were used to amplify the P. falciparum lactate dehydrogenase (ldh) gene as a control for a single-copy gene. Amplifications were carried out in 96-well plates (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using a CFX real-time PCR machine (Bio-Rad). Conditions for qPCR were 95°C for 15 minutes, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds. The cycle threshold (CT) was manually set to the level reflecting the best kinetic PCR parameters, and melting curves were analyzed. Relative copy number was estimated based on the ΔΔ CT method (2ΔΔct), as ([CTmdr1 – CTldh]sample – [CTmdr1 – CTldh]3D7).

Each reaction was carried out in triplicate, and the 3D7 and Dd2 P. falciparum reference strains were used to calibrate one and two pfmdr1 copies, respectively. Assays with a SD > 25% were repeated. Samples with 1.69–2.49 values were deemed to have two copies; 2.50–3.49, three copies; 3.50–4.49, four copies; 4.50–5.49, five copies; and 5.50–6.49, six copies, as previously described.34 Samples showing multiple pfmdr1 copies were tested again in an independent assay, and the measurement with a lower SD was chosen for analysis. Validated assays, in which pfmdr1 copy values of the 3D7 strain were normalized to 1, ranged from 1.80 to 2.25 for the Dd2 strain.

PCR amplification and sequencing of pfmdr1.

A PCR was set up to amplify a large 3,870-bp region of pfmdr1. The primary PCR primers (FWD) 5′-ACA AAA AGA GTA CCG CTG AAT TAT TTA G-3′ and (REV) 5′-GTC CAC CTG ATA AGC TTT TAC CAT ATG-3′ amplified the expected 3,870-bp product under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 52°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 4 minutes; and final extension at 65°C for 10 minutes. Then, two nPCRs were performed to amplify two shorter fragments.33 To capture SNPs at codons 86 and 184, the nested primers (FWD) 5′-CCG TTT AAA TGT TTA ACC TGC ACA AC-3′ and (REV) 5′-GCC TCT TCT ATA ATG GAC ATG GTA TTG-3′ amplified the expected 578-bp product under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 52°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 1 minute; and final extension at 65°C for 5 minutes. To capture SNPs at codons 1032, 1042, and 1246, the nested primers (FWD) 5′-TTT AAA GAT CCA AGT TTT TTA ATA CAG GAA GC-3′ and (REV) 5′-CTT ACT AAC ACG TTT AAC ATC TTC CAA TG-3′ amplified the expected 924-bp product under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 54°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 1.5 minutes; and final extension at 65°C for 5 minutes. The primary and nPCR volumes contained Platinum® PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen) and were set up in a final volume of 15 μL and 30 μL, respectively, and containing 1.5 μL genomic DNA (primary PCR) or 3 μL primary PCR product (nPCR). For sequencing the upstream fragment, the primers (FWD) 5′-GCT GTA TTA ATC AGG AGG AAC ATT ACC-3′ and (REV) 5′-CAA ACA TAA ATT AAC GGA AAA ACG CAA G-3′ were used. To sequence the downstream fragment, the primers (FWD) 5′-AAG CTA TTG ATT ATA AAA ATA AAG GAC AAA AAA GAA G-3′ and (REV) 5′-GGA CAT ATT AAA TAA CAT GGG TTC TTG AC-3′ were used. Sequences were analyzed using Sequencher version 5.1 software. Samples with low quality were resequenced using an increased amount of template DNA.

Statistical analysis.

Raw data were organized using Microsoft Excel. Comparison between two groups as RSA data between microscopist and antimalarial IC50 values per pair of antimalarial drugs were tested using the Mann–Whitney U test. To compare more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s posttest to find out the different one were used. Spearman’s test was used to find any correlation per pair of antimalarial drugs. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). P-values < 0.5 were deemed significant.

RESULTS

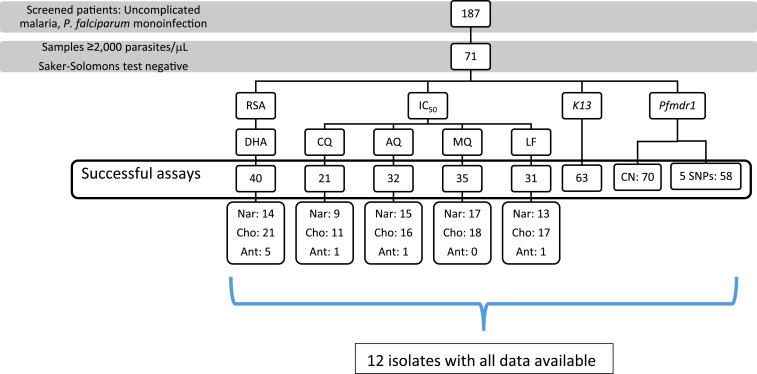

A total of 187 patients were screened for this study, and 71 were enrolled for susceptibility assays (Figure 1). Thirty-eight percent (27/71) were women. The median age was 25 (IQR: 18–35) years, and the median parasitemia was 3,400 (IQR: 2,000–6,828) parasites/μL. All patients were queried for CQ self-medication in the last month and tested by the Saker-Solomon test.35 Only patients with a negative result were enrolled for susceptibility assays. Ten patients were excluded because of a positive Saker-Solomon test.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

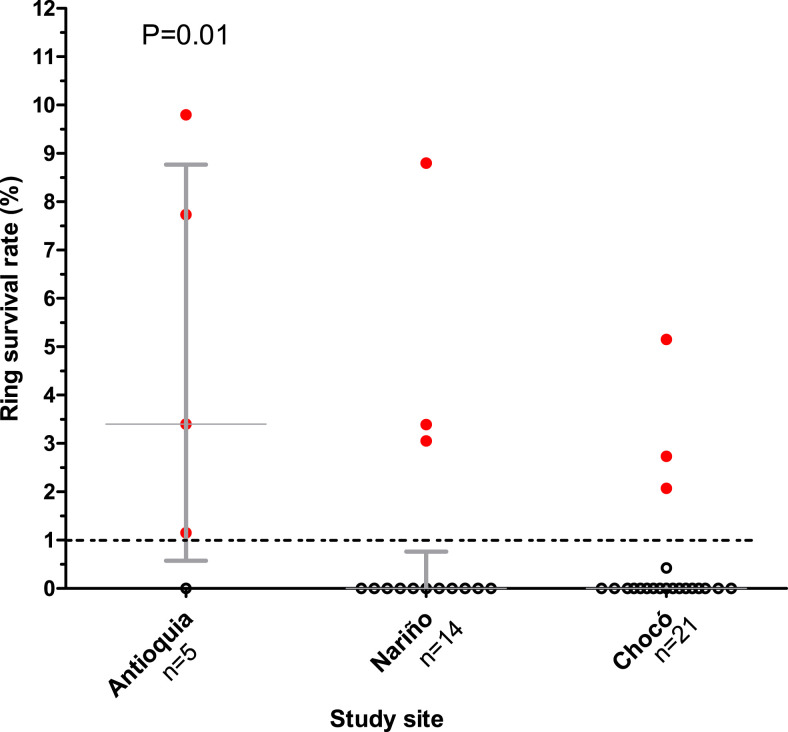

Ex vivo ring survival rates of P. falciparum isolates from three endemic areas in Colombia.

Isolates were collected from patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in the states of Nariño (n = 14), Choco (n = 21), and Antioquia (n = 5) (Figure 1). Forty of 71 samples (56.3%) were successfully evaluated by the RSA method. The median ring survival percentages were 0.0% for the Nariño (IQR: 0.0–0.6) and Chocó (IQR: 0.0–0.0) isolates, and 2.9% (IQR: 1.1–9.9, microscopist 1) and 3.9% (IQR: 0.0–7.6, microscopist 2) for the Antioquia isolates. There were no significant differences (Mann–Whitney U test P = 0.67) between the values obtained by both microscopists at each study site. No > 20% discrepancy between two microscopists was observed (range 0.7–10.2%). Therefore, we used the observations with the lowest IQR data for the analysis. Nine isolates had ring survival percentages > 1% (Figure 2). The highest ring survival percentages were found in isolates from Antioquia state (median 2.9% [IQR: 1.1–9.9]) and were significantly different from the survival rates of both Chocó and Nariño isolates (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ex vivo ring survival rates according to the study site. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

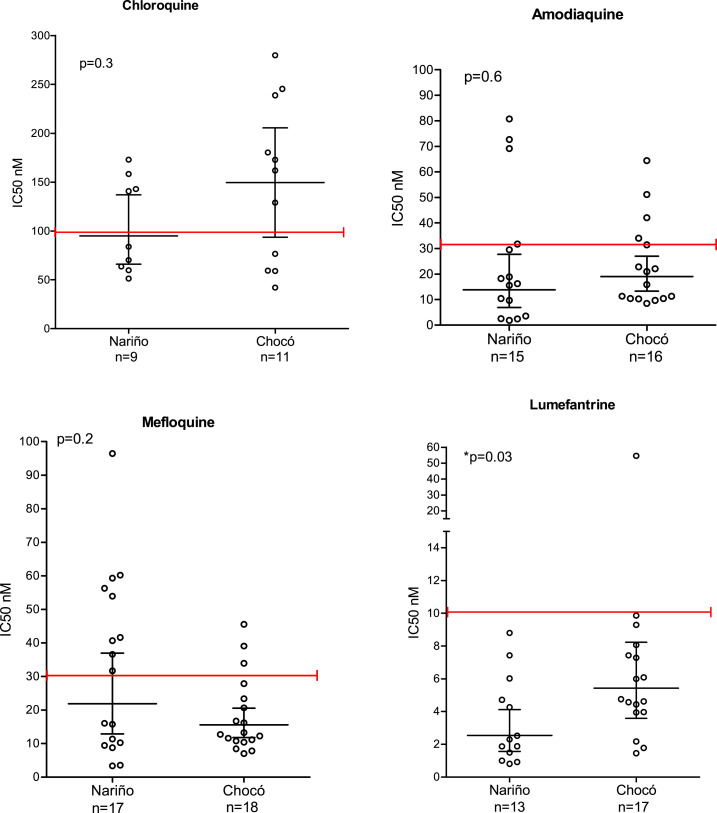

Fifty % inhibitory concentration values for CQ, AQ, MQ, and LF.

The percentages of interpretable assays for each antimalarial according to the core IVART platform were as follows: CQ 29.6% (21/71), AQ 45% (32/71), MQ 49.3% (35/71), and LF 43.7% (31/71) (Figure 1). The three batches of pre-dosed plates used in this study passed quality control, with P. falciparum strains 3D7 (CQ-sensitive) and FCR3 (CQ-resistant) showing CQ IC50 values < 15 nM and > 100 nM, respectively.

The geometric mean IC50 (95% CI) values for each antimalarial drug were as follows: CQ 109.8 nM (84.69–142.6), AQ 15.3 nM (10.6–22.2), MQ 18.4 nM (13.8–24.4), and LF 3.7 nM (2.7–5.2) (Figure 3). We found that 31.2% of isolates were resistant to AQ (> 30 nM), 34.3% to MQ (> 30 nM), and 3.2% to LF (> 10 nM). Interestingly, 52.4% of isolates were resistant to CQ (> 100 nM), although this drug has not been used to treat P. falciparum malaria in Colombia since 2000.36,37 Because of the limited number of samples, results from Antioquia were excluded from the analysis by state. No significant differences were found in antimalarial geometric mean IC50 values between Chocó and Nariño isolates, except for LF IC50 values (5.4 nM versus 2.5 nM, respectively; Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.03) (Figure 3). CQ and AQ geometric mean IC50 values tended to be higher for Chocó isolates, whereas the MQ geometric mean IC50 value tended to be higher for Nariño isolates. When analyzing the whole data set, significant positive correlations were observed for AQ–MQ (Spearman r2 = 0.76) and LF–MQ (Spearman r2 = 0.59) IC50 comparisons (Supplemental Table S3).

Figure 3.

Comparisons of antimalarial 50% inhibitory concentration values according to the study site. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Isolates with ring survival rates > 1% showed no differences in susceptibility to other antimalarials.

No significant differences were found when comparing the geometric mean IC50 values of different antimalarial drugs according to the ring survival rate (> 1% versus ≤ 1%). However, CQ IC50 values tended to be higher in isolates with ring survival percentage > 1% (Supplemental Table S4).

Mutant pfmdr1 alleles are present in P. falciparum isolates from different regions in Colombia.

Pfmdr1 gene copy number was successfully determined in 98.6% of samples (70/71). A single pfmdr1 copy was found in 92.9% (65/70) of samples, whereas two copies were present in 1.4% (1/70), three copies in 4.3% (3/70), and six copies in 1.4% (1/70). Regarding pfmdr1 SNPs, wild-type 86N was found in 100% (71/71), mutant 184F in 92.9% (66/71), wild-type 1034S in 91.5% (65/71), mutant 1042D in 92.9% (66/71), and mutant 1246Y in 16.9% (12/71) of samples; mutant 1034C and wild-type 1042C alleles were not found. We determined all 5 pfmdr1 SNPs for 81.7% (58/71) of samples, of which 79.3% (46/58) had double mutation NFSDD and 20.7% (12/58) had triple mutation NFSDY. Although the antimalarial IC50 values between NFSDD and NFSDY isolates were not significantly different, NFSDY isolates tended to have higher geometric mean IC50 values for all antimalarial drugs than NFSDD isolates (Supplemental Table S5).

The Pfkelch propeller was successfully sequenced in 88.7% (63/71) of isolates and were found to be wild type for mutations associated with artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia. Also, no other mutations previously reported in the Pfkelch propeller were found in our samples.

Parasitemia at day 3 posttreatment with AL.

Follow-up on day 3 after treatment was completed for 73.3% (52/71) of patients, all of whom had no asexual parasitemia detected by microscopy.

DISCUSSION

Ex vivo susceptibility assays and molecular marker screening are effective methods to monitor antimalarial resistance when efficacy studies are not possible. The WHO recommends performing efficacy studies for antimalarial treatment regimens every 3 years in endemic areas and complementary ex vivo or in vitro parasite susceptibility studies when possible.13 In Colombia, AL has been used as first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria since 2006.

We could freshly obtain 71 parasite isolates from uncomplicated malaria cases with confirmed P. falciparum mono-infection. Patients were passively recruited from three of the more endemic areas for malaria in Colombia. Together, the states of Chocó, Antioquia, and Nariño report about 90% of national cases annually. Ex vivo assays require some infrastructure (e.g., stable electricity) and well-trained personnel, which represent important challenges in remote endemic areas. Although surveying for changes in the prevalence of molecular markers associated with decreased antimalarial susceptibility has been suggested as an alternative tool to monitor variation in susceptibility patterns, neither ex vivo assays nor molecular markers can replace efficacy studies.13 Thus, this study represents an exploratory evaluation of the current status of artemisinin susceptibility in the three most epidemiologically relevant areas of Colombia.

We acknowledge some limitations regarding RSA assays. For example, 44.3% of assays were unsuccessful because of biological or technical issues such as lack of parasite growth, reduced quality of thin blood slides, and culture contamination. Regarding biological issues, there is evidence that resistance-associated mutations could cause impaired in vitro growth because of decreased fitness of resistant parasites.38 In addition, lack of growth in around 40% of fresh isolates has been previously found in Cambodian38 and Colombian15 studies. In other studies, intrinsic parasite properties seem to be more related to culture adaptation than to technical conditions, such as media supplements or parasitemia levels.39,40

In this study, no significant difference in parasitemia counts between two microscopists was found, even though the intrinsic subjectivity associated with light microscopy evaluations can be considerable. Regarding the initial parasitemia level, no statistical difference among the samples with unsuccessful and successful RSA was found (4,575 versus 5,808 parasites/µL, respectively). Morphological changes were evaluated as Witkowski et al.20 reported previously. Although automated and more objective methods to count parasitemia can eliminate this subjectivity, a good correlation between microscopy and flow cytometry has been described25,41; these technical conditions are not available in most endemic areas.

The in vitro RSA along with the day three positivity percentage, K13 mutations, and in vivo efficacy studies is the current method to evaluate artemisinin resistance. We observed a median 0.0% of ring survival percentage, as determined by two independent microscopists, among 40 successful assays. This study provides baseline ex vivo ring survival percentages for P. falciparum susceptibility to artemisinin derivatives, which could be used for future comparisons in Colombia. We had to change some ex vivo RSA conditions to evaluate higher numbers of isolates. For example, we had to decrease the parasitemia count inclusion criterion to 2,000 parasites/μL because finding samples with ≥ 10,000 parasites/μL, as Witkowski recommended, is practically impossible in Colombian field settings. Decreasing the parasitemia cutoff could have affected parasite growth in culture as well as microscopist performance in parasite counting. Therefore, this finding needs to be interpreted carefully because we found a few isolates with survival percentages > 1%. It is important to mention that for Asian settings, RSA rates greater than 1% suggest suspected artemisinin resistance. However, there are not enough data for RSA rates in parasites from South America, where this cutoff could vary. As we could not repeat the RSA on corresponding culture-adapted isolates, we could not confirm that the nine isolates with RSA rates > 1% are resistant to artemisinin. Thus, continued surveillance for decreased P. falciparum response to artemisinin will be challenging and will likely require confirmatory efficacy studies as well.

Our study followed WWARN recommendations and protocols to carry out ex vivo and in vitro assays. We took advantage of the statistical program IVART42 to analyze all antimalarial IC50 values. This program aims to standardize the quality control for input data and the parameters to perform IC50 calculations, enabling users to generate values that are comparable among study sites. The Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network suggests using the 3D7 P. falciparum strain as a standard reference for variation between laboratories settings.31,42,43 In this study, we performed quality control of pre-dosed plates using both the 3D7 strain (CQ-sensitive) and FCR-3 strain (CQ-resistant). We obtained a proportion of interpretable IC50 values for the different antimalarials evaluated, ranging from 21/71 for CQ to 35/71 for MQ. Several factors can produce erroneous measurements in this in vitro assay, including parasitemia level, low growth rate, and lack of curve adjustment (no core IC50 data). Indeed, only 12 isolates had successful RSA, IC50, pfmdr1, and pfkelch13 data (Supplemental Table S2), revealing a relatively low success rate of these in vitro assays under our field conditions.

We reviewed and compiled IC50 data previously published for the antimalarials of interest, reported in the same areas where we sampled parasites (Supplemental Table S1). Although we could confirm that > 50% of parasite isolates in our sample set remain CQ resistant (IC50 > 100 nM), their CQ IC50 values seem to have decreased in recent years (Supplemental Table S1). This scenario could be explained by the withdrawal of CQ for P. falciparum treatment since 2006, and, on the other hand, by continued self-medication with CQ (a common practice in endemic areas of Colombia44) and the fact that P. vivax, which co-circulates in the same areas as P. falciparum, is still treated with CQ.

Regarding ACT partner drugs such as AQ, MQ, and LF, we confirmed that most P. falciparum isolates from the Pacific region of Colombia (Nariño, Chocó) remain sensitive to these drugs (Figure 3), and the treatment is still efficacious in our country as previous studies have reported.10,11 Significant correlations between antimalarial drugs have been previously reported; for example, a significant positive correlation between MQ and LF IC50 values was found in a study in Senegal.45 That correlation has been associated with a similar mechanism of action for both antimalarial drugs, involving disruption of iron metabolism.46,47

This study screened for K13-propeller mutations in P. falciparum isolates from Colombia and found no mutations associated with ART resistance in Southeast Asia in our sample set. Our results are consistent with a global study of K13 mutations, where none were found among 14,037 parasite samples collected from 1997 to 2014 in different malaria-endemic areas from South America,48 and recent studies of Colombian isolates.10,33,49 However, Chenet et al.50 reported the independent emergence of C580Y mutant isolates from Guyana in 2010. This is very concerning given the increasing migration routes through the Amazon region, associated with illegal activities such as gold mining in Venezuela, Brazil, and Colombia.50 Unfortunately, at the time we tested for K13 mutations in our samples, the R561H K13 African mutation had not yet been identified.51

Although K13 molecular marker data suggest that no artemisinin resistance is yet present in Colombia, it is important to consider other possible reasons for the absence of K13-propeller mutations in this study, such as low genetic diversity in circulating parasites, impairment of parasite biological fitness by mutations that are not passed to the next generation, and as-yet-undetectable mutations. In addition, it is unclear if Colombian isolates have a permissive genome (previous mutation in other genes) that favors the emergence of artemisinin resistance mutations as described for Cambodian isolates.52–54

Our study found 7.1% (5/70) of isolates had multiple (maximum 6) copies of pfmdr1. Our findings are consistent with those of a recent study that found 32% of isolates had > 1 copy of pfmdr1.10 Amplification of pfmdr1 has been strongly associated with increased risk for therapeutic failures in a recent study in South Asian settings.23,55,56 Although no ex vivo susceptibility data were obtained from multi-copy pfmdr1 isolates in our study, mainly due to lack of ex vivo growth in culture, the circulation of multi-copy pfmdr1 isolates in Colombia should be managed carefully because of the strong association with higher IC50 values for artemisinin partner drugs (e.g., MQ and LF).34,55,57 Pfmdr1 mutations at positions 86, 184, 1034, 1042, and 1246 have been associated with increased IC50 values for the ACT partner drugs MQ and LF. However, in South America, the correlation between mutant alleles and IC50 values has not been clearly defined because of low genetic diversity and poor study quality.58–60

We found a higher frequency of the double-mutant pfmdr1 haplotype NFSDD (79.3%), also previously reported in isolates from the Colombian Pacific coast by Echeverry et al.61 In addition, we found that 20.7% of isolates had the triple-mutant haplotype NFSDY, which is common in South America but rare in Africa.62 Such triple-mutant isolates have been associated with higher IC50 values for different antimalarial drugs, which is consistent with our findings.43,63 A recent study showed that the parasite population circulating in the Pacific coast region of Colombia has very low genetic diversity, suggesting that a high probability of sampling the same clone during a single year could explain our finding of only 2 pfmdr1 haplotypes.64 Although not statistically significant, the IC50 values for LF seem to be increasing slightly over the years. For example, LF IC50 was 2.7 nM in 2008, 7.7 nM in 2013,10 and 3.7 nM in 2015 (this study).

The unexpected identification of P. falciparum isolates from Colombia with increased ex vivo RSA rates should be managed with care, because, although none of the isolates carried K13-propeller mutations associated with artemisinin resistance, they did carry increased pfmdr1 copy number. Therefore, continual surveillance for emergence of resistance to artemisinin and its partner drugs should be mandatory in Colombia and neighboring countries. Controlled efficacy studies in patients receiving AL are urgently needed in the country.

Supplemental tables

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the patients and their families for participating and making this study possible, and government organizations in the field: Divino Niño Hospital in Nariño, Ismael Roldan Hospital in Chocó, and Nuestra Señora del Carmen Hospital in Antioquia.

Note: Supplemental tables appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization , 2016. World Malaria Report 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colombia INdSd 2015, Boletin Epidemiologico Semana 52, 35–37.

- 3.Castellanos A, Chaparro-Narváez P, Morales-Plaza CD, Alzate A, Padilla J, Arévalo M, Herrera S, 2016. Malaria in gold-mining areas in Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 111: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arévalo-Herrera M, Lopez-Perez M, Medina L, Moreno A, Gutierrez JB, Herrera S, 2015. Clinical profile of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections in low and unstable malaria transmission settings of Colombia. Malar J 14: 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaparro-Narváez PE, Lopez-Perez M, Rengifo LM, Padilla J, Herrera S, Arévalo-Herrera M, 2016. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of complicated malaria in Colombia, 2007–2013. Malar J 15: 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore DV, Lanier JE, 1961. Observations on two Plasmodium falciparum infections with an abnormal response to chloroquine. Am J Trop Med Hyg 10: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osorio LE, Giraldo LE, Grajales LF, Arriaga AL, Andrade AL, Ruebush TK, Barat LM, 1999. Assessment of therapeutic response of Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in an area of low malaria transmission in Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 61: 968–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatz C, et al. 2018. Treatment of acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria with artemether-lumefantrine in nonimmune populations: a safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78: 241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrasquilla G, Barón C, Monsell EM, Cousin M, Walter V, Lefèvre G, Sander O, Fisher LM, 2012. Randomized, prospective, three-arm study to confirm the auditory safety and efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine in Colombian patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 86: 75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aponte S, Guerra Á, Álvarez-Larrotta C, Bernal SD, Restrepo C, González C, Yasnot MF, Knudson-Ospina A, 2017. Baseline in vivo, ex vivo and molecular responses of Plasmodium falciparum to artemether and lumefantrine in three endemic zones for malaria in Colombia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 111: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivera MJ, et al. 2020. Artemether-lumefantrine efficacy for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Choco, Colombia after 8 years as first-line treatment. Am J Trop Med Hyg 102: 1056–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdul-Ghani R, Al-Maktari MT, Al-Shibani LA, Allam AF, 2014. A better resolution for integrating methods for monitoring Plasmodium falciparum resistance to antimalarial drugs. Acta Trop 137: 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO , 2010. WHO, Global Report on Antimalarial Drug Efficacy and Drug Resistance: 2000–2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Restrepo-Pineda E, Arango E, Maestre A, Do Rosário VE, Cravo P, 2008. Studies on antimalarial drug susceptibility in Colombia, in relation to Pfmdr1 and Pfcrt. Parasitology 135: 547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aponte SL, et al. 2011. Sentinel network for monitoring in vitro susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to antimalarial drugs in Colombia: a proof of concept. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 106 (Suppl 1): 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arango E, Carmona-Fonseca J, Blair S, 2008. In vitro susceptibility of Colombian Plasmodium falciparum isolates to different antimalarial drugs. Biomedica 28: 213–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witkowski B, et al. 2013. Reduced artemisinin susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum ring stages in western Cambodia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57: 914–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dondorp AM, et al. 2009. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 361: 455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairhurst RM, Dondorp AM, 2016. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Microbiol Spectr 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witkowski B, et al. 2013. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis 13: 1043–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amaratunga C, Witkowski B, Dek D, Try V, Khim N, Miotto O, Ménard D, Fairhurst RM, 2014. Plasmodium falciparum founder populations in western Cambodia have reduced artemisinin sensitivity in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58: 4935–4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ariey F, et al. 2014. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 505: 50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phyo AP, et al. 2016. Declining efficacy of artemisinin combination therapy against P. falciparum malaria on the Thai-Myanmar border (2003–2013): the role of parasite genetic factors. Clin Infect Dis 63: 784–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarning J, Rijken MJ, McGready R, Phyo AP, Hanpithakpong W, Day NP, White NJ, Nosten F, Lindegardh N, 2012. Population pharmacokinetics of dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine in pregnant and nonpregnant women with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56: 1997–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witkowski B, Menard D, Amaratunga C, Fairhurst RM, 2014. Ring‐stage Survival Assays (RSA) to Evaluate the In‐vitro and Ex‐vivo Susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to Artemisinins Health. [Google Scholar]

- 26.WWARN , 2011. In Vitro Module, W., Preparation of Predosed Plates. WWARN Procedure. [Google Scholar]

- 27.WWARN , 2011. In Vitro Module, W., Estimation of Plasmodium falciparum Drug Susceptibility Ex Vivo by HRP2. WWARN Procedure. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noedl H, Attlmayr B, Wernsdorfer WH, Kollaritsch H, Miller RS, 2004. A histidine-rich protein 2-based malaria drug sensitivity assay for field use. Am J Trop Med Hyg 71: 711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noedl H, Bronnert J, Yingyuen K, Attlmayr B, Kollaritsch H, Fukuda M, 2005. Simple histidine-rich protein 2 double-site sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for use in malaria drug sensitivity testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49: 3575–3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rathod PK, McErlean T, Lee PC, 1997. Variations in frequencies of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 9389–9393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WWARN , 2011. In Vitro Module, W. In Vitro Module: Data Management and Statistical Analysis Plan (DMSAP) Versión 1.1 2013. Available at: invitro@wwarn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN, 1993. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol 61: 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montenegro M, Neal AT, Posada M, De Las Salas B, Lopera-Mesa TM, Fairhurst RM, Tobon-Castaño A, 2017. K13-propeller alleles, Mdr1 polymorphism, and drug effectiveness at day 3 after artemether-lumefantrine treatment for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Colombia, 2014–2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61: e01036-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim P, et al. 2013. Ex vivo susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to antimalarial drugs in western, northern, and eastern Cambodia, 2011–2012: association with molecular markers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57: 5277–5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mount DL, Nahlen BL, Patchen LC, Churchill FC, 1989. Adaptations of the Saker-Solomons test: simple, reliable colorimetric field assays for chloroquine and its metabolites in urine. Bull World Health Organ 67: 295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osorio L, Pérez LeP, González IJ, 2007. Assessment of the efficacy of antimalarial drugs in Tarapacá, in the Colombian Amazon basin. Biomedica 27: 133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pérez MA, Cortés LJ, Guerra AP, Knudson A, Usta C, Nicholls RS, 2008. Efficacy of the amodiaquine+sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine combination and of chloroquine for the treatment of malaria in Córdoba, Colombia, 2006. Biomedica 28: 148–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaorattanakawee S, et al. 2015. Attenuation of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro drug resistance phenotype following culture adaptation compared to fresh clinical isolates in Cambodia. Malar J 14: 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White J, et al. 2016. In vitro adaptation of Plasmodium falciparum reveal variations in cultivability. Malar J 15: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Claessens A, Affara M, Assefa SA, Kwiatkowski DP, Conway DJ, 2017. Culture adaptation of malaria parasites selects for convergent loss-of-function mutants. Sci Rep 7: 41303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amaratunga C, Neal AT, Fairhurst RM, 2014. Flow cytometry-based analysis of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in the ring-stage survival assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58: 4938–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wirjanata G, et al. 2016. Analysis of ex vivo drug response data of Plasmodium clinical isolates: the pros and cons of different computer programs and online platforms. Malar J 15: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodrow CJ, et al. 2013. High-throughput analysis of antimalarial susceptibility data by the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN) in vitro analysis and reporting tool. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57: 3121–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diaz G, Lasso AM, Murillo C, Montenegro LM, Echeverry DF, 2019. Evidence of self-medication with chloroquine before consultation for malaria in the southern pacific Coast Region of Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 100: 66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fall B, et al. 2011. Ex vivo susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Dakar, Senegal, to seven standard anti-malarial drugs. Malar J 10: 310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basco LK, Bickii J, Ringwald P, 1998. In vitro activity of lumefantrine (benflumetol) against clinical isolates of Plasmodium falciparum in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42: 2347–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson DW, Langer C, Goodman CD, McFadden GI, Beeson JG, 2013. Defining the timing of action of antimalarial drugs against Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57: 1455–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ménard D, et al. 2016. A Worldwide map of Plasmodium falciparum K13-propeller polymorphisms. N Engl J Med 374: 2453–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knudson A, et al. 2020. Spatio-temporal dynamics of Plasmodium falciparum transmission within a spatial unit on the Colombian Pacific Coast. Sci Rep 10: 3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chenet SM, et al. 2016. Independent emergence of the Plasmodium falciparum kelch propeller domain mutant allele C580Y in Guyana. J Infect Dis 213: 1472–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uwimana A, et al. 2020. Emergence and clonal expansion of in vitro artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H mutant parasites in Rwanda. Nat Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Conway DJ, 2007. Molecular epidemiology of malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev 20: 188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sibley CH, 2015. Infectious diseases. Understanding artemisinin resistance. Science 347: 373–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MalariaGEN Plasmodium falciparum Community Project , 2016. Genomic epidemiology of artemisinin resistant malaria. Elife 5: e08714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veiga MI, Ferreira PE, Jörnhagen L, Malmberg M, Kone A, Schmidt BA, Petzold M, Björkman A, Nosten F, Gil JP, 2011. Novel polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum ABC transporter genes are associated with major ACT antimalarial drug resistance. PLoS One 6: e20212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Price RN, et al. 2006. Molecular and pharmacological determinants of the therapeutic response to artemether-lumefantrine in multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Clin Infect Dis 42: 1570–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phompradit P, Muhamad P, Wisedpanichkij R, Chaijaroenkul W, Na-Bangchang K, 2014. Four years’ monitoring of in vitro sensitivity and candidate molecular markers of resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate-mefloquine combination in the Thai-Myanmar border. Malar J 13: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mita T, Tanabe K, Kita K, 2009. Spread and evolution of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance. Parasitol Int 58: 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montoya P, Tobón A, Blair S, Carmona J, Maestre A, 2007. Polymorphisms of the pfmdr1 gene in field samples of Plasmodium falciparum and their association with therapeutic response to antimalarial drugs and severe malaria in Colombia. Biomedica 27: 204–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le Bras J, Durand R, 2003. The mechanisms of resistance to antimalarial drugs in Plasmodium falciparum. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 17: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Echeverry DF, Holmgren G, Murillo C, Higuita JC, Björkman A, Gil JP, Osorio L, 2007. Short report: polymorphisms in the pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes of Plasmodium falciparum and in vitro susceptibility to amodiaquine and desethylamodiaquine. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77: 1034–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valderramos SG, Fidock DA, 2006. Transporters involved in resistance to antimalarial drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27: 594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Veiga MI, Dhingra SK, Henrich PP, Straimer J, Gnädig N, Uhlemann AC, Martin RE, Lehane AM, Fidock DA, 2016. Globally prevalent PfMDR1 mutations modulate Plasmodium falciparum susceptibility to artemisinin-based combination therapies. Nat Commun 7: 11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Echeverry DF, Nair S, Osorio L, Menon S, Murillo C, Anderso TJ, 2013. Long term persistence of clonal malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum lineages in the Colombian Pacific region. BMC Genet 14: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.