Significance Statement

Because current management of the rapid renal-function decline in AKI is merely supportive, deeper understanding of the AKI-perturbed molecular pathways is needed to identify targets with potential to lead to improved treatment. In a murine AKI model, the authors used single-cell RNA sequencing, single-molecule in situ hybridization, and protein expression analyses to create the first comprehensive renal cell type–specific transcriptional profiles for multiple AKI stages. Their findings revealed a marked nephrogenic signature and surprising mixed-identity cells (expressing markers of different cell types) in the injured renal tubules. Moreover, the authors identified potential pathologic epithelial-to-stromal crosstalk and several novel genes not previously implicated in AKI, and demonstrated that older onset age exacerbates the AKI outcome. This work provides a rich resource for examining the molecular genetics of AKI.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, single-cell, renal developmental genes, cellular crosstalk

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Current management of AKI, a potentially fatal disorder that can also initiate or exacerbate CKD, is merely supportive. Therefore, deeper understanding of the molecular pathways perturbed in AKI is needed to identify targets with potential to lead to improved treatment.

Methods

We performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) with the clinically relevant unilateral ischemia-reperfusion murine model of AKI at days 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, and 14 after AKI onset. Using real-time quantitative PCR, immunofluorescence, Western blotting, and both chromogenic and single-molecule in situ hybridizations, we validated AKI signatures in multiple experiments.

Results

Our findings show the time course of changing gene expression patterns for multiple AKI stages and all renal cell types. We observed elevated expression of crucial injury response factors—including kidney injury molecule-1 (Kim1), lipocalin 2 (Lcn2), and keratin 8 (Krt8)—and of several novel genes (Ahnak, Sh3bgrl3, and Col18a1) not previously examined in kidney pathologies. AKI induced proximal tubule dedifferentiation, with a pronounced nephrogenic signature represented by Sox4 and Cd24a. Moreover, AKI caused the formation of “mixed-identity cells” (expressing markers of different renal cell types) that are normally seen only during early kidney development. The injured tubules acquired a proinflammatory and profibrotic phenotype; moreover, AKI dramatically modified ligand-receptor crosstalk, with potential pathologic epithelial-to-stromal interactions. Advancing age in AKI onset was associated with maladaptive response and kidney fibrosis.

Conclusions

The scRNA-seq, comprehensive, cell-specific profiles provide a valuable resource for examining molecular pathways that are perturbed in AKI. The results fully define AKI-associated dedifferentiation programs, potential pathologic ligand-receptor crosstalk, novel genes, and the improved injury response in younger mice, and highlight potential targets of kidney injury.

AKI is a group of syndromes characterized by abrupt renal-function decline associated with pronounced mortality, comorbidities in other organs, and increasing hospitalization trends.1–4 Moreover, AKI episodes can initiate or exacerbate CKD, a debilitating condition with limited therapeutic options, which could progress to ESKD.5–7 Thus, examining the molecular targets underlying early AKI response is paramount for treatment development.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a powerful, unbiased approach to dissect cell-specific transcriptome changes in the developing and adult kidney, both human and murine.–17 A recent scRNA-seq report delineated the transcriptional signatures of resident renal macrophages in multiple species.18 Several studies revealed the cell-specific gene expression changes defining renal pathologies, including diabetic kidney disease and allograft rejection.19–21 Bulk RNA-seq examined AKI progression and renal fibrosis22,23; however, scRNA-seq might help identify cell-specific molecular targets of AKI.

This study aimed to create a comprehensive atlas of single-cell transcriptional changes of AKI response in the clinically relevant unilateral ischemia/reperfusion (UIR) model, inducing severe renal injury without significant mortality.24–26 The observed transcriptional changes were reproduced using specific gene and protein expression analyses. We report potential novel AKI markers, mixed identities, and a profibrotic phenotype in the injured tubules. Consistent with a recent report, we observed a widespread proinflammatory phenotype in multiple injured tubular segments.27 Moreover, we revealed potential AKI-induced, epithelial-to-stromal crosstalk, which supports the role of proximal tubules in orchestrating fibrosis.28 We also examined the age effect on AKI response, finding that younger mice recover whereas the older mice develop fibrosis after identical UIR.

Methods

Animals

The Institutional Care and Use Committee of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center reviewed and approved all animal procedures used in this study. UIR26,29 was induced via atraumatic left renal pedicle clamping for 30 minutes at 37°C in 4-week-old, male, Swiss-Webster (CFW) mice, and the kidneys were harvested at day 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, and 14 after the UIR (n=1 per day 1, 2, and 4; n=2 per day 7, 11, and 14) for scRNA-seq and histologic verification. As we and others30,31 observed, the contralateral kidney, although not injured directly, undergoes the compensatory changes, including proteo-metabolomic compensation for the injured kidney. Thus, kidneys harvested from the naive mice of the same strain and age were used as controls. Validations were performed on an additional set of animals treated with the identical UIR procedure (n=3–6 per group). For examining the effects of age on the AKI outcome, the equivalent UIR was induced in the 10-week-old, male, Swiss-Webster mice, and the kidneys were harvested at UIR day 1, 7, and 14 (n=4 per group).

Single-Cell Suspension Preparation and scRNA-seq Procedure

The 4-week-old, male, CFW mice treated with the UIR procedure were intraperitoneally injected with 100 μl heparin (100 U/ml), anesthetized in an isoflurane chamber, and euthanized via exsanguination followed by cervical dislocation at day 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, and 14 after the UIR (n=1–2 per group). The kidneys were perfused with ice-cold Dulbecco PBS (DPBS) via the aorta before harvesting to remove red blood cells (RBCs), and the left (injured) and the right (contralateral) kidneys from the UIR-treated mice were collected along with the control kidneys obtained from the naive mice. The kidneys were placed on ice-cold DPBS, decapsulated, bisected lengthwise, and sliced coronally. The cortical regions were then finely minced with a sterile razor blade until tissue was homogenous and clumps were broken down, and 65 mg of the minced tissue was placed in 2 ml digestion buffer containing 3 mg/ml Collagenase Type 2 (Worthington), 1.5 mg/ml ProNase E (P6911; Sigma), 62.5 U/ml DNAse (A3778; Applichem), and 5 mM calcium chloride made up in DPBS. The digest mix was incubated in a 37°C water bath for 20 minutes with vigorous trituration with a 1 ml pipet every 2 minutes. Aliquots (5 µl) were taken every 5 minutes and visualized using a microscope to ensure adequate digestion. After 20 minutes, the digest mix was added to two 1.5 ml low-adhesion tubes and was then incubated in a thermomixer for 5 minutes at 37°C while shaking at 1400 RPM. The digest mix was subsequently added to a 70-µM filter (130-098-462; Miltenyi) stacked on a 30-µM filter (130-098-458; Miltenyi) on a 50-ml conical tube. The filters were rinsed with 10 ml PBS/BSA 0.01% and the flow through was then transferred to a 15-ml conical tube. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 350 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 100 µl PBS/BSA. The cells were visualized and if >30% were RBC, the RBC lysis step was performed: 1 ml of RBC lysis buffer (R7757; Sigma) was added, the cells were triturated 20× with a 1-ml pipet, and the cells were then incubated for 2 minutes on ice. Ice-cold PBS/BSA (12 ml) was then added to dilute the RBC lysis buffer. If no RBC lysis was necessary, then 12 ml ice-cold PBS/BSA was added to the cells. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 350 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was then discarded, and the cells resuspended in 2 ml PBS/BSA. Cells were analyzed with a hemocytometer using trypan blue and the concentration was adjusted to 100,000 cells/ml for the droplet-based scRNA-seq procedure (DropSeq) based on a protocol from Macosko et al.12

The remaining tissue slices from each kidney were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS overnight (O/N) at 4°C, paraffin embedded for histologic assessment, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for the molecular analysis. The validation animals (n=3–4 per group) treated with the identical UIR protocol were harvested at the same time points (day 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, and 14), the kidney tissue was fixed in 4% PFA O/N at 4°C, and then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for the further analysis.

scRNA-seq Data Analysis

The generated cDNA libraries were quantified using an hsDNA chip and were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 using one flow cell (about 300 million reads) per sample. The raw fastqs were processed by aligning read2 to the mm10 genome using bowtie2-2.2.7 using the -k 1 option. The aligned reads were tagged with their corresponding unique molecular identifier and bar code from read1. Each aligned read was tagged with its gene name. An expression matrix was generated by counting the number of unique molecular identifiers per gene per cell. The total number of 54,730 cells was analyzed (control, 6736; day 1, 3574; day 2, 4110; day 4, 6415; day 7, 8772, day 11, 10,713; day 14, 14,410).

Cell-type clusters and markers genes were identified using the R version 3.6.1 library Seurat version 3.1.0.16,32 All clustering was unsupervised, without driver genes. The influence of the number of unique molecular identifiers was minimized by regression within the ScaleData function. Initial cell filtering selected cells that expressed >500 genes. Genes included in the analysis were expressed in a minimum of three cells. Only one read per cell was needed for a gene to be counted as expressed per cell. The resulting gene expression matrix was normalized to 10,000 molecules per cell and log transformed.12 Cells containing high percentages of mitochondrial, >30%, and hemoglobin genes, >0.025%, were filtered out. Genes with the highest variability among cells were used for principal component analysis. Cell clusters were determined by the Louvain algorithm by calculating k-nearest neighbors and constructing a shared nearest neighbor graph, with the most common resolution set at 0.7. Dimension reduction was performed using the Python implementation of Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), using significant principal components determined by JackStraw plot. Marker genes were determined for each cluster using the Wilcoxon rank sum test within the FindAllMarkers function, using genes expressed in a minimum of 10% of cells and a fold-change threshold of 1.3. Over/under clustering was verified via gene expression heatmaps. For the highly variable genes, the mean.var.plot selection method was used within the FindVariableFeature function, with the cutoffs for the mean at (0.0125,3) and dispersion (0.5,Inf), which resulted in approximately 2000 variable features.

The integrative, all-time-point analysis of renal cell populations was deposited to the interactive website (https://research.cchmc.org/PotterLab/scIRI/). The trajectory analysis was performed on the control and UIR day 1, 4, 7, and 14 single-cell suspensions using Monocle2.33 Heatmaps characterizing the mixed-identity-cells cluster were generated by comparing relative gene expression between the UIR day 1 renal cell populations (Figure 1F). To address the potential influence of multicelled droplets within the dataset, the DoubletDecon algorithm34 was used to filter out doublets. The original Seurat object from the day 1 UIR dataset was converted to the DoubletDecon format and processed using the mouse species, rhop set to 1.2, the number of synthetic doublets made set at 200, and only 50 set to false. This found 697 cells, called doublets. These doublets were removed from the dataset and the filtered cells were reprocessed as previously described. Even after doublet removal, the multilineage population remained. To address the potential ambient RNA influence, single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH; also known as RNAscope) was counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of DNA and nuclei content, which helped to identify the single cells exhibiting mixed transcriptional identities.

Figure 1.

scRNA-seq reveals proximal tubule dedifferentiation and mixed-identity cells in the ischemia reperfusion–induced AKI. (A) UIR procedure scheme 1. (B) The experimental timeline. (C) UMAP plots show the renal cell populations in the control and UIR day 1. UIR resulted in substantial reduction of mature proximal tubule population. (D) CISH validates the AKI-induced proximal tubule dedifferentiation. The differentiated proximal tubule marker Slc34a1 is abundantly expressed in the control kidney and dramatically reduced in UIR day 1, with some remaining expression in the outer cortex. Original magnification, control and UIR day 1, ×4; zoom into the outer cortex, ×40. (E) Kim1 (green), Aqp2 (red), Slc34a1 (purple) RNAscope. Similar to (D), RNAscope validates the reduced expression of Slc34a1 in UIR day 1 kidneys. Conversely, expression of the injury marker Kim1 is greatly increased at UIR day 1. Original magnification, control and UIR day 1, ×4; zoom, ×60. (F) Heatmap shows the relative marker gene expression in UIR day 1 renal cell types. Yellow color represents expression level above the mean, black color represents the mean, and purple/blue represents expression level below the mean. The heatmap shows genes elevated in renal cell populations relative to each other, based on the z-score. AKI induces the elevated ectopic gene expression in the UIR day 1 cell populations. Note the cluster of mixed-identity cells exhibiting particularly high stochastic expression of markers of many different mature cell types. Original magnification, 4×, 2500 μm; 40×, 100 μm; 60×, 25 μm. Related to Supplemental Figures 1–4 and Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Endoth, endothelial; CD, collecting duct; Interc, intercalated. (A) Reprinted from ref. 120, with permission from Elsevier.

Heatmaps characterizing the global injury–induced gene expression changes were generated by comparing genes elevated in the UIR day 1 and 4 “proximal tubules,” “injured proximal tubules” (“injured prox”), and “mixed-identity cells” to the normal proximal tubules. The separate heatmap was generated to demonstrate the injury-induced transcription factors, particularly renal developmental genes.

Putative signaling interactions between proximal tubules, injured proximal tubules, stromal cells, and mixed-identity cells were assessed. Potential receptor-ligand interactions were found by pairing a cell type expressing a ligand with a cell type expressing its receptor pair. A receptor or ligand was considered expressed in a cell type if it had an average normalized expression of >0.25. Receptor-ligand pairs were determined using the curated receptor-ligand database by the RIKEN FANTOM5 project.35 Receptor-ligand pairings for each cell type were visualized by a chord diagram using the R package circlize.36

Differential gene expression between control proximal tubules, injured proximal tubules, and mixed-identity cells was determined by Wilcoxon rank sum test within the Seurat FindMarkers function, using a log fold-change threshold of 0.5 and an adjusted P value cutoff of 0.01. Venn diagrams were prepared with the R package VennDiagram.37

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Gene expression changes identified by scRNA-seq were validated using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Three to six mice from the original scRNA-seq cohort and the additional validation cohort were used per each group. Total RNA was isolated from the homogenized whole-kidney lysates with RNA Stat-60 extraction reagent (CS-111; Amsbio) and purified using the GeneJET RNA purification kit (KO732; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cDNA was synthesized with the iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (1708841; Bio-Rad). qPCR was performed with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (4304437; Thermo Fisher Scientific) on the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR system. The details of the TaqMan primers are presented in Supplemental Table 1. The reported Ct values are the mean of two replicates of the same cDNA sample. The target-gene Ct values were normalized to the eukaryotic 18S ribosomal RNA endogenous control and presented as the fold change.

Western Blotting

We validated the RNA expression changes detected by the scRNA-seq with Western blots. Three to six mice from the original scRNA-seq cohort and the additional validation cohort were used per each group. Total protein was extracted from the homogenized whole-kidney lysates using the M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (78501; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with protease (78430; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and phosphatase (10 mM sodium orthovanadate) inhibitors. Protein (10 µg) was separated on 4%–12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, blocked with the Odyssey Blocking Buffer (927-40000; LI-COR), and incubated with the target-recognizing primary antibodies (AF1817, 0.25 µg/ml, kidney injury molecule-1 [Kim1], goat; R&D Systems; JM-3819-100, 0.5 µg/ml, lipocalin 2 [Lcn2], rabbit; MBL; AF114, 0.1 µg/ml, Cd45, goat; R&D Systems) O/N at 4°C. On the next day, the membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline with 0.02% Tween 20 and incubated with the secondary fluorescent antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) in the darkness. The target protein levels were normalized to the endogenous control (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, mouse, MAB374, 1:500; Millipore Sigma). The membranes were scanned on the LI-COR Odyssey CLx imaging system.

Chromogenic In Situ Hybridization

Chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) riboprobes were generated from the genomic DNA or cDNA with PCR and labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) using the DIG RNA Labeling Mix (11277073910; Roche) by in vitro transcription, and the primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Primer specificity was checked with Basic Local Alignment Search Tool analysis. PFA-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 6-µm kidney sections were subjected to the CISH protocol as previously described.38,39 On day 1, deparaffinated and dehydrated sections were incubated with Proteinase K (1 μg/ml) for 30 minutes at 37°C, fixed in 4% PFA for 30 minutes at RT, acetylated in 0.25% acetic anhydride, and hybridized for 14–16 hours at 70°C with the antisense riboprobes. Sense riboprobes were used for the negative controls. All day-1 procedures were performed in ribonuclease-free conditions. On the second day, sections underwent a series of saline sodium citrate buffer washes and were incubated with the anti-DIG-AP Fab fragments (11093274910, 1:1000; Roche) O/N at 4°C, followed by a series of posthybridization washes and color development with BM Purple (11442074001; Roche). Color-development time varied from several hours to 3–4 days, depending on the target gene expression levels. For the immunofluorescence (IF) colabeling, the protocol was modified by adding the primary antibody recognizing the target (EP1628Y, 1:100, keratin 8 [Krt8], rabbit; Abcam; sc-25,287, 1:50, Aqp1, mouse; Santa Cruz) to the anti-DIG-AP antibody mixture and incubating O/N at 4°C.40 The next day, the sections were incubated with the fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 hour at RT in darkness, followed by the posthybridization washes and color development, according to the CISH protocol. DAPI (62248, 1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) treatment for nuclei labeling was performed after the color development; the sections were mounted with Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium (H-1000; Vector Laboratories). For the double CISH/IF staining, treatment with the antisense riboprobe and secondary antibodies only was used as the negative control. For the immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, the sections were subjected to the endogenous peroxidase quenching, blocking, and primary antibody incubation (ab64064, 1:100, Cd24a, rat; Abcam) O/N at 4°C, followed by signal detection with the ImmPRESS reagent kit with DAB substrate.41 CISH and IHC images were obtained on the Nikon Ti2 wide-field microscope. RGB images of CISH/IHC were taken with an Andor Zyla 4.2 plus camera and a Lumencor LIDA RGB transmitted light source.

Single-Molecule Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (using RNAscope)

RNAscope probes were purchased from Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Inc. and are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. RNAscope was performed with the Multiplex Fluorescent V2 Assay (323100; Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Inc.) on freshly sectioned, PFA-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 6-µm kidney sections according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the deparaffinized and dehydrated kidney sections underwent the endogenous peroxidase quenching, heat-induced target retrieval, and protease digestion, followed by incubation with up to three target riboprobes for 2 hours at 40°C. All the aforementioned steps were performed in ribonuclease-free conditions. Next, tyramide signal amplification was performed, according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and conjugated to an Opal dye (PerkinElmer). The sections were treated with DAPI (62248, 1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and mounted with Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium (H-1000). The negative controls were treated with the signal amplification reagents, but no target riboprobes, and processed alongside the experimental sections.

Fluorescent Microscopy and Quantitative Image Analysis

The double CISH/IF imaging was performed on a Nikon A1R HD confocal Ti-E microscope using the galvanometric scanner. The CISH signal was captured both using a transmitted light detector, to detect absorption of photons by the chromogenic substrate, and as near-infrared fluorescence of the BM Purple, using a 647-nm laser for excitation and capturing fluorescence data >740 nm with a 740-nm, long-pass filter.42,43 Transmitted images of chromogenic substrate are shown in grayscale images and fluorescence of the color development reagent (BM Purple) is shown as color (cyan or magenta).

For the RNAscope, single-transcript quantification, Z-stacks of approximately 6 µm from multiple (nine to 12 per sample) focal planes were obtained on a 60× water immersion objective at Nyquist resolution on the Nikon Ti-E A1R HD confocal with the resonant scanner. The images were processed with NIS-Elements AR 5.2.00 artificial intelligence denoise algorithm (https://www.microscope.healthcare.nikon.com/products/confocal-microscopes/a1hd25-a1rhd25/nis-elements-ai) and stitched into the single image with the NIS-Elements AR stitching tool. All images within an experimental group were obtained with the same optical configuration. We first identified individual renal tubules based on the marker gene expression using the “manual surfaces” algorithm in Bitplane Imaris 9.3.1.44 We then identified the transcripts using the “spots” algorithm, with identical spot diameter and quality used for the experimental groups and the controls. To quantify the transcript number per tubule, we used the Matlab XT function “split spots into surfaces.” We normalized the obtained transcript number to the tubule volume and presented the average of all renal tubules (approximately 50–70 tubules) captured in the image.

Statistical Analyses and Reproducibility

The gene expression changes identified by scRNA-seq were reproduced in a separate cohort of experimental mice of the same strain, age, and sex, treated with the identical UIR procedure. Three to six mice per group were used for the qPCR and Western blot analysis. Data were presented as mean±SEM. To determine the statistical significance, P values were generated using one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni and Holm test with P<0.05 representing a statistically significant difference. The significance is shown compared with the control group. For the original RNAscope experiments, nine to 12 Z-stack images per animal were analyzed (n=1 animal per time point). For the additional RNAscope mixed-identity-cell validation, 12 Z-stacks per animal (n=3 controls, n=4 UIR day 1, n=2 UIR day 4, n=2 UIR day 14) were used to quantify Slc34a1; Uromodulin (Umod)–positive tubules. Transcript numbers were quantified using Bitplane Imaris 9.3.1. as described above; data were analyzed with t test or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni and Holm test when comparing the two or multiple conditions, respectively; P<0.05 represented a statistically significant difference. For the correlation analysis, R2 was obtained and analyzed with Pearson correlation test; P<0.05 represented a statistical significance. The Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of biologic processes was performed in the ToppGene Suite,45 with a P-value cutoff of 0.05. The gene clusters enriched in renal cell populations were generated with ToppCluster46 with Bonferroni correction and a P-value cutoff of 0.05. The ToppCluster analysis graph was generated with the Fruchterman–Reingold graph layout algorithm, showing individual genes associated with biologic processes enriched in the renal cell population of interest.

Results

scRNA-seq Reveals Proximal Tubule Dedifferentiation and Mixed-Identity Cells in the Ischemia Reperfusion–Induced AKI

scRNA-seq was carried out with the clinically relevant UIR model in Swiss-Webster, 4-week-old male mice at multiple AKI stages (Figure 1, A and B).8,12,16 Renal cell populations were identified using unsupervised clustering. UMAP plots16 demonstrated resulting cell clusters, including podocytes, proximal and distal tubules, loop of Henle, intercalated and principal collecting duct compartments, endothelial cells, pericytes, macrophages, T cells, and stromal/pericytes cells (Figure 1C, Supplemental Figure 1A).

AKI caused reduced expression of the mature proximal tubule marker Slc34a1, consistent with dedifferentiation47–49 and significant elevation of two clinically recognized tubular injury markers, Kim1 (also known as Havcr1)50 and Lcn251–54 (Figure 1C, Supplemental Figure 1, A and B). As we and others55–57 show, Kim1 is predominantly expressed in the injured prox, whereas Lcn2 labels the loop of Henle, distal tubule, and collecting ducts of UIR day 1. These findings were reproduced with CISH and FISH (RNAscope) on an independent validation cohort of 4-week-old UIR mice (Figure 1, D and E, Supplemental Figure 1C).

AKI also elicited the “cell cycle prox” cluster, upregulating cell cycle markers, such as Mki67 (Supplemental Figure 1B). Hematoxylin and eosin staining confirmed the pronounced AKI-induced tubular injury (Supplemental Figure 1D). Thus, we showed that the UIR model comprises all classic AKI features.58,59

Functional enrichment GO analysis45 of proximal tubules in UIR day 1 versus control showed the crucial downregulation of the proximal tubule homeostasis pathways, including transmembrane transport (Slc34a1, Aqp1, Lrp2, Slc7a13, Slc22a6), oxidation-reduction (Slc37a4, Slc25a2, Aco1, Aco2, Cyp2e1, Miox), and fatty acid catabolism (Acadl, Acadm, Cd36, Cpt1a, Crot, Slc27a2) (Supplemental Figure 1E, Supplemental Table 2).60,61 Conversely, AKI induced apoptotic processes (Acin1, Tnfrsf12a, Clusterin [Clu], Nfkbia, Lgals1, Ctsd), cell cycle regulation (Ccnd1, Ccnl1, Ctnnb1, Pcna), granulocyte activation and cytokine response (C3, S100a11, Lcn2, Cstb, Anxa2), and cellular response to oxygen (Mgst1, Gpx3, Aoc1) in the injured prox.

We noticed that AKI caused an elevated level of ectopic gene expression compared with the control, as shown by the heatmaps that demonstrate the relative marker gene expression in the UIR day 1 and normal renal cell populations (Figure 1F, Supplemental Figure 2A). Particularly, UIR day 1 exhibited a unique cluster located between proximal tubules, loop of Henle, distal tubule, and collecting duct on the UMAP, characterized by unexpected overlapping expression of the collecting duct marker Aquaporin 2 (Aqp2)62 and the loop of Henle marker Umod,63 along with both proximal (Kim1) and distal (Lcn2) nephron tubule segment injury markers (Supplemental Figure 2, B and C). These mixed-identity cells showed particularly elevated stochastic expression of many differentiated kidney cell type markers, including renal tubule segments (Aqp2, Slc12a3, Slc12a1), activated fibroblasts (Ctgf, Col1a2, Cald1),64–66 and immune cells (Ccl5, Lyz2) (Figure 1F). Doublet removal did not affect the presence and gene expression signature of this cluster, verifying the mixed transcriptional identity (Supplemental Figure 3, Supplemental Table 3). Moreover, this scRNA-seq finding was reproduced in two independent UIR animal cohorts using single-molecule-resolution FISH. RNAscope data revealed UIR induced increase of Umod, Aqp2, Slc12a3, and Slc12a1 transcripts in the Slc34a1-positive tubules, which was verified by Imaris quantification (Figure 2, A–C, Supplemental Figure 4A). Importantly, nuclear DAPI staining verified the presence of multiple renal tubule segment markers within the same cell (Figure 2A, yellow arrows). Quantitative analysis also revealed the significantly declined Slc34a1 expression in the UIR day 1; the experiment specificity was confirmed with the negative control (Supplemental Figure 4, B–E). The presence of Aqp2 transcripts in Slc34a1-positive tubules demonstrates the marked plasticity of adult injured cells, because the proximal tubule and the collecting duct arise from different developmental lineages.67,68

Figure 2.

AKI induces reactivation of the renal developmental program in the adult kidney. (A) Representative images of Umod (red), Slc34a1 (purple), and DAPI (blue) RNAscope. Note the ectopic expression of the loop of Henle marker gene Umod in the Slc34a1-positive tubules shown with the yellow pointers. Original magnification, ×60, 0.03 μm Nyquist zoom, scale 10 μm, maximal intensity projection from approximately 6-μm Z-stacks. (B and C) Imaris quantification of Umod and Aqp2 transcripts in the Slc34a1-positive UIR day 1 versus control tubules, 12 Z-stacks (50–70 tubules) per group, t test. ****P<0.0001. Data are presented as the transcript number normalized to the tubule volume. For Umod analysis, three control kidneys (12 Z-stacks per animal) and four UIR day 1 kidneys (12 Z-stacks per animal) from two independent batches were analyzed. (D and E) Feature plots show the elevated Cd24a and Sox4 expression in UIR day 1. (F) CISH shows the elevated Cd24a expression in the UIR day 1 renal tubules. Cortex, purple frames (left); medulla, black frames (right). Related to Supplemental Figures 2–4 and Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Original magnification, ×40. Scale, 100 μm.

AKI Induces Reactivation of the Renal Developmental Program in the Adult Kidney

In addition to the mixed identities, scRNA-seq identified elevated nephrogenic genes in the adult injured kidney. Particularly, AKI caused upregulation of Transcription Factor SRY-related HMG Box-4 (Sox4) (Figure 2D), which is strongly expressed in the developing kidney.69 However, Sox4 had not been previously reported in adult AKI. UIR-treated kidney also elevated Cd24a (Figure 2E), encoding a cell-surface sialoglycoprotein expressed in the uninduced metanephric mesenchyme during nephrogenesis.70 Human CD24 is also implicated in kidney development and tubular epithelial differentiation.71 We validated Cd24a elevation in both cortical and medullary tubules (Figure 2F). Notably, scRNA-seq showed that Sox4 and Cd24a were elevated in multiple tubular compartments, which recapitulates their developing kidney spatial-expression patterns.69,72,73

UIR day 2 showed persistent injury, with continued proximal tubule dedifferentiation, presence of mixed-identity cells, immune infiltration (Figure 3, A–C) and exacerbated tubular damage (Supplemental Figure 5A). Renal tubular injury persisted through UIR day 4 and 7; however, we observed signs of recovery, including increased Slc34a1 and reduced Kim1 levels (Figure 3, A–C). Consistent with the previous work,74 we observed that both time points exhibited a large immune infiltration, represented by macrophages and T cells (Figure 3A). The mixed-identity cells were no longer present at day 7; however, we identified the “dedifferentiated-prox” cluster, marked by the proximal tubular genes (Aqp1, Slc7a12, Cdh2)75–78 and a strong renal developmental signature, including crucial kidney induction regulators (Sprouty1, Nephronectin, Foxc1, Osr2, Notch2, Jag1) (Supplemental Table 4).72,73,79–83

Figure 3.

scRNA-seq reveals the transcriptional landscapes of AKI recovery. (A) UMAPs show renal cell populations in the UIR day 2, 4, 7, and 14. Day 11 is shown in Supplemental Figure 3, because it was very similar to day 14. (B) Slc34a1 CISH, UIR day 2, 4, 7, and 14. Slc34a1, a marker of differentiated proximal tubules, showed continued, severely reduced, expression at day 2, which steadily recovered by day 14. Original magnification, ×4; zoom into the cortex, ×40. (C) Kim1 (green), Aqp2 (red), Slc34a1 (purple), DAPI (blue) RNAscope, UIR day 2, 4, 7, and 14. The injury marker Kim1 showed strong expression at day 2, less expression at day 4, and very little expression at day 7, which returned to normal levels by day 14. Original magnification, ×4, zoom into the cortex, ×60. (D) UMAP shows the integrated, all-time-point analysis of change in renal cell populations over the AKI course. Note the colocalization of renal cell populations from UIR day 1 and 2, outlining the most prominent injury, and UIR day 11 and 14, which reflect AKI recovery and also colocalize with the control. Renal cell populations from the intermediate stages (UIR day 4 and 7) are localized between the “injured” and “recovered” groups. (E) Trajectory analysis of the control, UIR day 1, 4, 7, and 14 renal cell populations shows the transition from injured to recovered renal tubules. Numbers 1 and 2 represent the significant branch points of differentiation. Scale, ×4, 2500 μm; ×40, 100 μm; ×60, 25 μm. Related to Supplemental Figures 5–8 and Supplemental Tables 4 and 5.

Both scRNA-seq and RNAscope showed further recovery at UIR day 11 and 14, defined by restored Slc34a1 expression, absent Kim1-positive injured proximal tubules, and decreased immune infiltration (Figure 3, A–C, Supplemental Figure 5, B–D). Injury resolution was confirmed with hematoxylin and eosin staining and analysis of Slc34a1, Kim1, Lcn2, and immune cell marker Cd45 expression over the AKI course (Supplemental Figure 5, A and E–H). Consistent with the scRNA-seq findings, quantitative Imaris analysis showed the significant elevation of double Slc34a1; Umod–positive tubules at day 1 and 4, which resolved at day 14 (Supplemental Figure 6A). Although a small dedifferentiated-prox cluster was still present at UIR day 11, the kidney developmental signature was markedly weaker at this point (Supplemental Table 4); these cells were absent at UIR day 14. Similar to the control, UIR day 14 proximal tubules were enriched with transmembrane transport and metabolic pathways (Supplemental Figure 6B).

The integrative, all-time-point analysis revealed that UIR day 11 and 14 renal cell populations colocalize with the control, outlining the AKI recovery; whereas UIR day 4 and 7 are positioned between the recovered and the most injured (day 1 and 2) time points, highlighting the intermediate stages of AKI response (Figure 3D). The trajectory analysis showed the transition from injured to recovered stages over the AKI course (Figure 3E). Notably, integrated analysis demonstrated enrichment of renal developmental genes—including Cd24a, Sox4, Lhx1, Hes1, Pou3f3, and Hox genes—among the genes exhibiting significant expression level changes over the AKI course (Supplemental Figures 6C and 7A).84–88 Analysis of the UIR day 1 and 4 proximal-tubule and mixed-identity clusters, compared with the normal adult proximal tubules, identified injury-induced gene expression signature, enriched with the apoptotic (Acin1, Clu, Lgals1), proinflammatory (Kim1, Lcn2, S100a9, S100a8), profibrotic (Vimentin [Vim], Col18a1, Ezh2), and developmental (Npnt, Sox4, Ch24a, Aqp2) genes (Supplemental Figure 8, Supplemental Table 5). The comprehensive atlas of AKI-induced gene expression changes (shared at https://research.cchmc.org/PotterLab/scIRI/) allows for searching of the target gene spatiotemporal pattern and expression level, which might provide a valuable resource for the community.

Sox4 and Cd24a Label the Proximal and Distal Tubule Injury

Next, we examined the gene expression signature marking the proximal tubule injury over the AKI course. We performed differential analysis of genes elevated in the injured prox compared with control proximal tubules at UIR days 1, 2, 4, and 7, and identified 183 overlapping genes, including Cd24a and Sox4 (Figure 4A, Supplemental Table 6). The shared genes were also enriched with proinflammatory pathways, such as leukocyte activation and degranulation (Lcn2, Lgals1, Anxa2, S100a11, Cstb) and viral processes (Kim1, Ifi27, Cd74, Anxa2). Importantly, AKI induced a persistent IFN-response signature (Ifi27, Ifit2, Ifit3, Ifitm3, Ifi44), not only in the injured proximal tubules, but also in the collecting ducts and distal tubules (Supplemental Table 2). Differential analysis of the genes elevated in the mixed-identity cells over the control proximal tubules at UIR days 1, 2, and 4 identified 99 common genes, including Umod (loop of Henle) and Aqp2 (collecting duct) (Figure 4B, Supplemental Table 6). GO analysis revealed elevation of cytokine response (Ifi27, Ifitm3, Anxa2, Lcn2), vesicle fusion (Sparc, Tubb5, Tagln2, Lgals3), and regulation of programmed cell death (Clu, Nfkbia, Ubb, Pea15a, Lgals1, Ctsd) (Supplemental Figure 9A). Importantly, AKI elicited abundant Clu upregulation in many injured kidney compartments (Supplemental Table 2), which might play a protective role.89 Previous work90 reported urinary Clu as a kidney injury marker, along with cystatin C and β2-microglobulin, two other AKI-induced genes identified by scRNA-seq (Supplemental Tables 2 and 6). Notably, ToppCluster analysis46 of the genes shared by the mixed-identity cells at UIR day 1, 2, and 4 identified both Cd24a and Sox4 (Supplemental Figure 9B). pPCR performed on an independent animal cohort validated the injury-induced elevation of Cd24a and Sox4 shown by scRNA-seq, which reversed by UIR day 14 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Sox4 and Cd24a label the proximal and distal tubule injury. (A) Venn diagram shows the genes elevated in the injured prox at UIR day 1, 2, 4, and 7. Injured proximal tubule gene expression patterns were compared with control proximal tubule. Note 183 overlapping genes highlighted by the red box. (B) Venn diagram shows the genes elevated in the mixed-identity cells at UIR day 1, 2, and 4. Mixed-identity cell gene expression patterns were compared with control proximal tubule. A total of 99 genes overlapping between the time points are highlighted by the red box. (C) qPCR shows Sox4 and Cd24a expression over the AKI course. These nephrogenic genes showed significant elevation at days 1, 2, and 4. n=4–6 animals per group, analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. **P<0.01 compared with control. Scale, ×4, 2500 μm; ×40, 100 μm; ×60, 25 μm. (D) Feature plots show cells expressing Slc34a1 (green), Sox4 (red), and both (blue) in UIR day 4 versus control. In the control, very few proximal tubule cells expressed Sox4 (many with Slc34a1, blue dots). In UIR day 4, Sox4 was predominantly expressed by injured proximal tubules, showing an inverse relationship with Slc34a1. (E) RNAscope with Slc34a1 (pink), Sox4 (green), and Kim1 (white) probes, and DAPI (blue) in the UIR day 4. In the cortical region of the UIR day 4 kidney, the dedifferentiated proximal tubules, with reduced Slc34a1 expression, showed robust expression of Kim1 and Sox4. Original magnification, ×60, 0.14 μm/px Nyquist zoom, maximal intensity projection from Z-stack; scale, 50 μm. (F) Feature plots show Lcn2 (green), Cd24a (red), and Double (blue) positive cells in UIR day 1 versus control. Whereas Lcn2 and Cd24a showed very weak expression in the control kidney, UIR day 1 showed striking colocalization between Lcn2 and Cd24a in the distal tubule, loop of Henle, and collecting duct. Cd24a was also elevated in the injured proximal tubules and mixed-identity cells. The feature plots show gene expression without color gradient outlining the expression level. (G) RNAscope images show Lcn2 (green) and Cd24a (pink) colocalization at UIR day 1, white pointers. Cd24a is also elevated in Slc34a1-positive (cyan) proximal tubules. DAPI, blue. Original magnification, ×60, 0.21 μm/px Nyquist zoom, maximal intensity projection (MaxIP) from Z-stack; scale, 50 μm. Related to Supplemental Figures 9–12 and Supplemental Table 6.

We further examined the developmental gene expression in the adult injured kidney and found that Sox4 displayed a strong inverse relationship with Slc34a1 starting at UIR day 4, when the injury resolution begins (Figure 4D). Quantitative RNAscope analysis revealed Sox4 was abundantly enriched in the proximal tubules at UIR days 1 and 2; however, it was predominantly confined to the remaining Kim1-positive injured proximal tubules at UIR days 4 and 7, with a substantial difference between Sox4 transcript number in the Kim1- versus Slc34a1- enriched proximal tubules (Figure 4E, Supplemental Figure 9, C and D), demonstrating Sox4 labels proximal tubule dedifferentiation.

Next, we noticed the striking overlap between Cd24a and Lcn2 in the loop of Henle, distal tubule, and collecting duct of the UIR-treated kidney, with significant correlation between Cd24a and Lcn2 transcript numbers (Figure 4, F and G, Supplemental Figure 10, A and B). Previous work49 and we demonstrated the injured proximal tubules also upregulate Cd24a, which was validated with RNAscope (Supplemental Figure 10C). However, quantitative analysis revealed Cd24a is substantially more enriched in the Lcn2-positive tubules than in the Slc34a1-positive proximal tubules throughout the AKI response (Supplemental Figure 10D), demonstrating that Cd24a primarily marks distal nephron tubule injury in the adult kidney. Importantly, the injury-induced RNA expression changes predicted by scRNA-seq were reproduced on the protein level, as shown by Cd24a IHC (Supplemental Figure 11). Moreover, Western blotting demonstrated significant elevation of CD24 (human Cd24a homolog) in the human kidney biopsy specimens obtained from patients supported by dialysis, compared with those not on dialysis, highlighting the potential significance of reactivation of the injury-induced developmental program (Supplemental Figure 12).

Novel Gene Expression Signatures of AKI

scRNA-seq revealed AKI induces striking, widespread upregulation of several genes, including Clu and IFN response genes. Also, AKI caused extensive Spp1 (also known as Osteopontin) upregulation in tubular, stromal, and immune cells, which was validated with CISH (Figure 5, A and B). Consistent with previous work,91 we observed some normal Spp1 expression, mostly in the distal nephron tubule segment; however, UIR caused widespread Spp1 elevation in both medulla and cortex. Spp1 encodes a secreted phosphoprotein 1 (also known as Osteopontin) essential for bone metabolism and immune system activation, which is implicated in multiple renal pathologies, including diabetic nephropathy, allograft rejection, and renal cell carcinoma (RCC).92 We also observed the pronounced elevation of AKI-induced tubular cytokeratin (Krt7, Krt8, Krt18; Figure 5C, Supplemental Table 2), which is a known marker of epithelial cell stress and tumor progression.23,93,94 Particularly, Krt8 was shown to play a crucial role in RCC.95 Combined CISH and immunofluorescence revealed that Krt8 transcript elevation was accompanied by increased protein; moreover, some of the tubules exhibited expression of both injury markers (Supplemental Figure 13A). Both Krt8 and Spp1 remained upregulated at UIR day 4 and lowered to the normal levels by day 14 (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

AKI causes extensive Osteopontin and Keratin signaling in the injured kidney. (A) Feature plots show Spp1 expression in control and UIR day 1 cell populations. Color gradient outlines the expression intensity. (B) Spp1 CISH, control versus UIR day 1. Original magnification, ×4; zoom into the cortex, ×40. Scale, 100 μm. (C) Feature plots show Krt8 expression in control and UIR day 1 cell populations. Color gradient outlines the expression intensity. (D) Combined Spp1 CISH (cyan) and Krt8 Immunofluorescence (red) shows the injury-induced Spp1 and Krt8 elevation in UIR day 1 and 4, resolving by UIR day 14. scRNA-seq-predicted Krt8 elevation is reproduced on the protein level. DAPI (blue), UIR day 1. Original magnification, ×20. Scale, 200 μm. TD, transmitted detector shows the chromogenic Spp1 CISH signal. Related to Supplemental Figure 13.

Our dataset identified additional novel genes not previously implicated in kidney pathologies. Sh3bgrl3 encodes a SH3 domain-binding protein 1, associated with guanosine 5ʹ-triphophatase, oxidoreductase, and antiapoptotic activity.96 The control kidney exhibited very low levels of Sh3bgrl3, whereas it was highly enriched in all tubular segments in UIR day 1 (Figure 6, A and B). Ahnak encodes the neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK, involved in pathogenesis of Miyoshi muscular dystrophy97 and tumor metastasis via TGF-β–induced, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.98 Both scRNA-seq and CISH showed that Ahnak is present in the control podocytes, endothelium, and stroma with minor collecting duct expression, whereas UIR caused marked Ahnak elevation in multiple tubular and stromal compartments (Figure 6, A and B, Supplemental Figure 13B).

Figure 6.

scRNA-seq reveals novel gene expression signatures of AKI. (A) Feature plots show Sh3bgrl3 and Ahnak expression in UIR day 1 versus control. Note that although both genes are nearly absent in the control proximal tubules and moderately expressed in the control collecting duct, AKI induces their robust elevation in multiple tubular segments. (B) Sh3bgrl3 and Ahnak CISH, UIR day 1 versus control. Note that Ahnak, which is normally expressed mostly in the glomeruli and stroma, is substantially elevated in the injured renal tubules. Original magnification, zoom into the cortex, ×40. Scale, 100 μm. (C) Myh9 CISH shows robust elevation in UIR day 1 and 2, which steadily declines at day 4 and 7, with reversal to the normal levels by day 14. Note the intratubular (red arrows) and glomerular (black stars) Myh9 expression induced by AKI. Original magnification, ×4; scale, 2500 μm. Zoom into the cortex (black frames), ×40; scale, 100 μm. (D) Feature plots show Myh9 expression in UIR day 1 versus control. Note the elevation in all tubular segments. (E) Myh9 CISH (magenta), Aqp1 IF (green), DAPI (blue), control versus UIR day 1. White pointers show Myh9 within Aqp1-positive tubules. Original magnification, 60× Nyquist 0.07 px/μm zoom, scale 25 μm. (F) qPCR shows Myh9, Sh3bgrl3, and Ahnak expression over AKI course, four to six animals per group, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni and Holm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with the control. Related to Supplemental Figure 13.

AKI also caused elevation of Myh9, encoding a nonmuscle myosin involved in cell motility, shape maintenance, and cytokinesis (Figure 5C). As we and others99,100 show, normal adult kidney moderately expresses Myh9 in the glomeruli, endothelium, and stroma; Myh9 is essentially absent in normal proximal tubules (Figure 5D). However, AKI caused striking Myh9 elevation in all renal tubules and glomeruli at UIR days 1 and 2 (Figure 6, C and D). Combined CISH/immunofluorescence validated AKI-induced Myh9 elevation within Aqp1-positive proximal tubules, not detectable in the control (Figure 6E).

qPCR on the validation cohort reproduced scRNA-seq-predicted Sh3bgrl3, Ahnak, and Myh9 upregulation, revealing the significant injury-induced elevation at UIR days 1, 2, and 4, which reversed by day 14 (Figure 6F).

scRNA-seq Identified AKI-Induced Fibrotic Proximal Tubule Phenotype and Novel Epithelial-to-Stromal Interactions

Next, we examined how AKI affects cell-to-cell communication in the kidney. We paired the cells enriched with ligand to the cells enriched for the corresponding receptor. We found the control proximal and distal tubules and the stromal cells might interact via calmodulin (Calm1, Calm2, Calm3), growth factor (Egf, Fgf1, Hbegf, Vegfa, Mdk, Igfbp4), and lipid metabolism (Lpl, Lrpap1, Psap) signaling (Figure 7A, Supplemental Table 7). We also found the stromal cells might influence proximal tubules via collagen signaling, because the stromal cells were enriched with Col1a1/1a2, Col3a1, Col4a1/4a5, and Col18a1, while the proximal tubules expressed their receptors. Our data also highlights potential pericyte-to-proximal tubule interactions via collagen, nidogen (Nid1, Nid2), matrix metalloproteinase (Timp2), and calmodulin signaling.

Figure 7.

scRNA-seq identifies novel epithelial-to-stromal interactions in adult AKI. (A) Circos plot of ligand-receptor interactions between the proximal (brown) and distal (blue) tubules, the stromal cells (green), and the stromal/pericyte cells (purple) in the normal kidney. The populations producing the putative ligand are labeled; directions of predicted ligand-receptor interactions are shown with the sharp ends of the arrows. The names of all putative ligands and receptors with respect to the cell populations are available in Supplemental Figure 14 and Supplemental Table 7. (B) Circos plot of ligand-receptor interactions between the proximal tubules (brown), injured proximal tubules (red), mixed-identity cells (green), distal tubules (blue), and the stromal cells (teal) in the UIR day 4 kidney. The populations producing the putative ligand are labeled; black arrows show Vim-Cd44 (highlighted in blue), Col18a1-Gpc4, and Col18a1-Itgb1 (highlighted in black) ligand-receptor pairs. Note the dramatic increase in the number of potential interactions compared with the control, using the same filters. The names of all putative ligands and receptors with respect to the cell populations are available in Supplemental Figure 15 and Supplemental Table 7. (C) Representative RNAscope image of control proximal tubules, Vim (green), Col18a1 (red), Slc34a1 (purple). Original magnification, 60×, 0.05 μm/px Nyquist zoom, maximal intensity projection from the Z-stack. Scale, 25 μm. (D) Representative RNAscope image of UIR day 4 proximal tubule, Vim (green), Col18a1 (red), and Slc34a1 (purple). Note the elevated Vim and Col18a1 inside the proximal tubule exhibiting lowered Slc34a1 level. Original magnification, 60×, 0.05 μm/px Nyquist zoom, maximal intensity projection from the Z-stack. Scale, 25 μm. Related to Supplemental Figures 13–15, Supplemental Videos 1 and 2, and Supplemental Table 7.

We then examined UIR day 4 as an intermediate injury response time point. Ligand-to-receptor analysis revealed a dramatic increase in the interactions between renal cell populations, particularly extracellular matrix signaling by the injured epithelial cells (Figure 7B, Supplemental Table 7). We observed that injured proximal tubules and mixed-identity cells elevated Vim, an activated fibroblast marker associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and kidney fibrosis (Supplemental Figure 13C).28,101–103 Moreover, we found the Vim receptor encoding gene Cd44104 was expressed in the stromal cells, suggesting pathologic tubular-to-stromal crosstalk (Figure 7B, Supplemental Table 7). Cd44 was also enriched in the injured proximal tubules and mixed-identity populations, suggesting injured renal epithelial cells not only interact with stromal cells, but crosstalk with each other.

Interestingly, we observed that AKI induced increase of Col18a1, encoding an extracellular, nonfibrillar basement membrane collagen.105 We and others72,73 show that Col18a1 is normally present mostly in the glomerulus, with some weak expression in the collecting duct (Supplemental Figure 13C). We found remarkable Col18a1 elevation in the injured proximal and distal tubules and the mixed-identity cells; moreover, the Col18a1 receptor encoding genes Gpc4 and Itgb1 were enriched in stromal cells, highlighting another potential epithelial-to-stromal interaction pathway (Figure 7B). These observations were validated by the qPCR and RNAscope, which revealed marked Vim and Col18a1 upregulation within the Slc34a1-positive proximal tubules at UIR day 1, 2, and 4, which later returned to the normal interstitial and periglomerular expression pattern (Figure 7, C and D, Supplemental Figure 13, D–F, Supplemental Videos 1 and 2). Other factors involved in injury-induced epithelial-to-stromal crosstalk included collagens (Col4a1, Col4a3, Col4a4), Lcn2, Ifitm2, Lgals3bp, and Spp1. The complete lists of epithelial-to-stromal interactions are available in the Supplemental Figures 14 and 15 and Supplemental Table 7. The negative controls for used RNAscope probes are provided in Supplemental Figure 16.

Increased Onset Age Exacerbates AKI Outcome

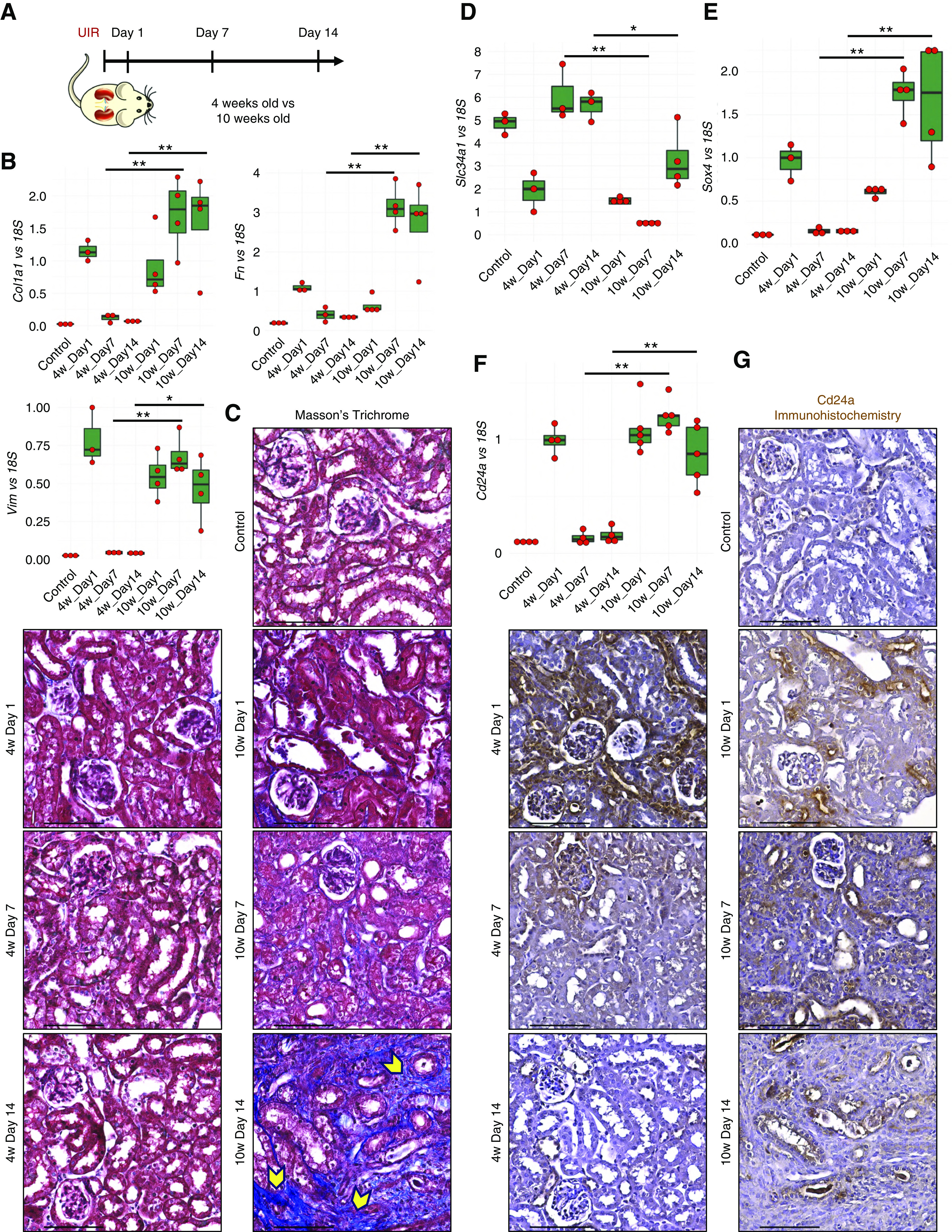

Next, we tested the effects of AKI onset age on the injury outcome.106–108 We induced identical UIR in 10-week-old, male, Swiss-Webster mice and revealed that, unlike the younger mice, they develop maladaptive AKI response, outlined by persistent proximal tubule dedifferentiation and unresolved Slc34a1 expression, fibrosis marker gene (Col1a1, Vim, Fn1) elevation, and extracellular matrix deposition by UIR day 14 (Figure 8, A–D). Notably, we observed that both Sox4 and Cd24a remained significantly elevated at UIR day 7 and 14 in the older animals compared with the younger ones (Figure 8, E and F). Moreover, Cd24a protein marked the injured renal tubules of the older mice throughout the AKI course, whereas it resolved in the younger animals by UIR day 14 (Figure 8G). Thus, we prove that AKI onset age defines whether the kidney undergoes repair or maladaptive remodeling, and that Sox4 and Cd24a levels might have a predictive value in determining the AKI outcome.

Figure 8.

Increasing onset age exacerbates AKI outcome. (A) Experimental outline. (B) qPCR shows the fibrosis markers Vim, Col1a1, and Fn1 expression over the AKI course, n=4–6 per group, t test, 4 weeks day 7 versus 10 weeks day 7, 4 weeks day 14 versus 10 weeks day 14. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (C) Masson trichrome staining shows fibrotic remodeling in the 10-week-old mice at UIR day 14. Note the abundant fibrotic remodeling (blue color on the Masson trichrome staining, yellow pointers) in the UIR day 14 of older mice, while UIR day 14 younger mice exhibit normal kidney histology. Original magnification, ×40. Scale, 100 μm. (D–F) qPCR shows Slc34a1, Sox4, and Cd24a expression over the AKI course, n=4–6 per group, t test, day 7, 4 weeks versus 10 weeks; day 14, 4 weeks versus 10 weeks. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (G) Cd24a IHC. Note persistent intratubular expression in the UIR 10-week-old mice, resolved in the UIR 4-week-old mice. Original magnification, zoom into the cortex, 40×. Scale, 100 μm. (A) The kidney image is reprinted from ref. 120, with permission from Elsevier.

Discussion

In this study, we used scRNA-seq to comprehensively characterize the changing gene expression patterns of all renal cell types after AKI, thereby providing a rich resource for further studies. Examining early AKI stages offers the benefit of detecting potentially reversible changes in the injured cells. Injured tubules showed dramatic dedifferentiation, including the elevation of renal developmental genes Sox4 and Cd24a. Of interest, Six2Cre;Sox4 mutants develop reduced nephron number and early ESKD.109–112 Further, Sox4 is implicated in numerous human malignancies, including RCC.112–114 Sox4 also drives the expression of embryonic genes in an epidermis wound model,115 suggesting similar function in AKI proximal tubule dedifferentiation. Whereas Sox4 expression marked the proximal tubule, the expression of the embryonic gene Cd24a116–118 marked distal nephron tubule segments. Importantly, CD24 elevation was detected in patients with CKD who were maintained on dialysis.

The scRNA-seq and RNAscope also identified the mixed-identity cells at multiple stages of AKI response. Cellular plasticity in the adult renal cells, particularly expression of the collecting duct marker Aqp2 in the Slc34a1-positive tubules, might indicate the significant AKI-induced dedifferentiation in the injured kidney, because normally it is only observed in early kidney development.9,13 To minimize the potential influence of doublets, the presence of mixed-identity cells was verified with the doublet removal analysis which did not affect the presence of this cluster. Moreover, the nuclear DAPI stain was used to identify the ectopic transcript expression within the single cells on the RNAscope data, thus minimizing the influence of ambient RNA on the analysis of injury-induced mixed identity.

scRNA-seq identified several genes previously not recognized in AKI, including a marked intratubular elevation of Ahnak, which is a downstream target of the uPA-nAChRα1 pathway associated with renal fibrosis.119 Intratubular elevation of Ahnak and other stromal genes—including Vim, Myh9, and Col18a1—showed the mesenchymal phenotype acquired by the injured epithelial cells. Moreover, the scRNA-seq showed a dramatic shift in ligand-receptor crosstalk in the UIR kidney, including potential pathologic epithelial-to-stromal interactions that could contribute to fibrosis.28

To ensure data reproducibility, we validated the scRNA-seq-identified transcriptional changes in multiple experiments, including single-molecule-sensitive FISH. The detected transcriptomic changes were also reproduced with protein expression analyses, proving the accompanying translational changes. Importantly, our dataset revealed elevation of several genes, including Cstb and S100a10, which were recently reported in the injured proximal tubules using translational profiling,27 thus crossvalidating the kidney injury signatures.

Increased AKI incidence and worsened outcomes are observed in older patients.106–108

In this study, we show that, whereas younger mice recover 2 weeks after UIR, the older mice develop maladaptive fibrotic remodeling, marked by persistent Sox4 and Cd24a elevation. Further study of the mechanisms behind the age-related differences in kidney injury recovery, and examining the AKI response in significantly advanced age, could lead to improved therapies that result in a youthful outcome in older patients.

Overall, this study reveals cell-specific transcriptional landscapes of AKI response, strengthening our understanding of AKI molecular genetics and highlighting potential cellular and molecular targets of kidney injury.

Disclosures

P. Devarajan has the patent “NGAL as a biomarker of kidney injury” licensed. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK120842 (to S. Potter) and P50DK096418 (to P. Devarajan), and an Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation Mallinckrodt Fellowship Award (to K. Drake).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of Dr. Jiang and Dr. Yutzey laboratories for CISH and FISH protocols; and the Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center Gene Expression Core, Confocal Imaging Core, and Veterinary Services Surgical Core members for assistance with imaging, scRNA-seq, and animal procedures.

Dr. Valeria Rudman-Melnick, Mr. Mike Adam, and Dr. S. Steven Potter prepared the manuscript; Dr. Valeria Rudman-Melnick assembled figures; Mr. Andrew Potter did kidney dissociation and scRNA-seq; Mr. Mike Adam analyzed the scRNA-seq data; Dr. Qing Ma and Dr. Valeria Rudman-Melnick induced UIR; Dr. Valeria Rudman-Melnick, Mr. Mike Adam, Dr. Prasad Devarajan, and Dr. S. Steven Potter developed experimental strategy and analyzed results; Dr. Valeria Rudman-Melnick, Mr. Saagar M. Chokshi, and Dr. Qing Ma did validation experiments; Dr. Meredith P. Schuh and Dr. J. Matthew Kofron provided guidance for imaging and RNAscope data analysis; and Dr. Keri A. Drake helped to cover the sequencing costs.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Data Sharing Statement

The scRNA-seq data were deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE139506. The integrative all-time-point analysis was deposited to https://research.cchmc.org/PotterLab/scIRI/. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. S. Steven Potter (Steve.Potter@cchmc.org).

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2020010052/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. UIR induced proximal tubule dedifferentiation, tubular damage and gene expression changes.

Supplemental Figure 2. AKI results in formation of the mixed identity cells in the adult kidney.

Supplemental Figure 3. Doublet removal does not affect the mixed identity cells presence.

Supplemental Figure 4. UIR induces quantitative changes in mixed identity and proximal tubular dedifferentiation.

Supplemental Figure 5. AKI persists through UIR day 4 and 7 and resolves by UIR day 14.

Supplemental Figure 6. AKI induced unique gene expression signatures in the injured proximal tubules and mixed identity cells.

Supplemental Figure 7. The integrated analysis reveals changes in transcription factor expression over AKI response.

Supplemental Figure 8. Injury induced gene expression analysis reveals enrichment of apoptotic, pro-fibrotic and developmental factors in the UIR induced proximal tubules and mixed identity cells.

Supplemental Figure 9. Sox4 labels proximal tubules dedifferentiation throughout the AKI course.

Supplemental Figure 10. Cd24a marks distal nephron tubule segment injury and correlates with Lcn2.

Supplemental Figure 11. UIR day 1 exhibits marked Cd24a protein elevation in the cortical and medullary tubules.

Supplemental Figure 12. Validation of AKI induced genes in the human kidney samples.

Supplemental Figure 13. Pro-fibrotic signaling in the injured kidney.

Supplemental Figure 14. Epithelial-to-stromal crosstalk in the normal kidney.

Supplemental Figure 15. Epithelial-to-stromal crosstalk in the UIR day 4.

Supplemental Figure 16. Negative controls for Sox4, Cd24a, Lcn2, Kim1, Slc34a1, Vim, Col18a1 RNAscope probes.

Supplemental Table 1. qPCR primers, riboprobes, CISH probe primer sequences.

Supplemental Table 2. UIR day 1 versus control gene expression analysis.

Supplemental Table 3. UIR day 1 marker gene after doublet removal.

Supplemental Table 4. The “dedifferenriated prox” UIR day 7 and 11 marker gene.

Supplemental Table 5. Analysis of AKI induced gene expression changes in the injured proximal tubules and mixed identity cells.

Supplemental Table 6. Differential analysis of genes elevated in the “injured prox” and “mixed identity cells” compared with the control over the AKI course.

Supplemental Table 7. Receptor-ligand interactions in control and UIR day 4 kidney.

Supplemental Video 1. RNAscope control proximal tubule, Vim (green), Col18a1 (red), Slc34a1 (purple), 60x Nyquist zoom 0.07 µm/px, scale 20 µm. Related to Figure 7.

Supplemental Video 2. RNAscope UIR day 1 proximal tubule, Vim (green), Col18a1 (red), Slc34a1 (purple), 60x Nyquist zoom 0.07 µm/px, scale 20 µm. Related to Figure 7. Note elevated Vim and Col18a1 in the Slc34a1 positive tubule.

References

- 1.Harding JL, Li Y, Burrows NR, Bullard KM, Pavkov ME: US trends in hospitalizations for dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury in people with versus without diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis 75: 897–907, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoste EAJ, Kellum JA, Selby NM, Zarbock A, Palevsky PM, Bagshaw SM, et al.: Global epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol 14: 607–625, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavkov ME, Harding JL, Burrows NR: Trends in hospitalizations for acute kidney injury — United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67: 289–293, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawhney S, Fraser SD: Epidemiology of AKI: Utilizing large databases to determine the burden of AKI. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 24: 194–204, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferenbach DA, Bonventre JV: Mechanisms of maladaptive repair after AKI leading to accelerated kidney ageing and CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 264–276, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu RK, Hsu CY: The role of acute kidney injury in chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 36: 283–292, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita K, Saritas T, Eiwaz MB, McClellan N, Coe I, Zhu W, et al.: The acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease transition in a mouse model of acute cardiorenal syndrome emphasizes the role of inflammation. Kidney Int 97: 95–105, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam M, Potter AS, Potter SS: Psychrophilic proteases dramatically reduce single-cell RNA-seq artifacts: A molecular atlas of kidney development. Development 144: 3625–3632, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunskill EW, Park JS, Chung E, Chen F, Magella B, Potter SS: Single cell dissection of early kidney development: Multilineage priming. Development 141: 3093–3101, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combes AN, Phipson B, Lawlor KT, Dorison A, Patrick R, Zappia L, et al. : Single cell analysis of the developing mouse kidney provides deeper insight into marker gene expression and ligand-receptor crosstalk [published correction appears in Development 146: dev182162, 2019 10.1242/dev.182162]. Development 146: dev178673, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochane M, van den Berg PR, Fan X, Bérenger-Currias N, Adegeest E, Bialecka M, et al.: Single-cell transcriptomics reveals gene expression dynamics of human fetal kidney development. PLoS Biol 17: e3000152, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, et al.: Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell 161: 1202–1214, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magella B, Adam M, Potter AS, Venkatasubramanian M, Chetal K, Hay SB, et al.: Cross-platform single cell analysis of kidney development shows stromal cells express Gdnf. Dev Biol 434: 36–47, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park J, Shrestha R, Qiu C, Kondo A, Huang S, Werth M, et al.: Single-cell transcriptomics of the mouse kidney reveals potential cellular targets of kidney disease. Science 360: 758–763, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ransick A, Lindström NO, Liu J, Zhu Q, Guo JJ, Alvarado GF, et al. : Single-cell profiling reveals sex, lineage, and regional diversity in the mouse kidney. Dev Cell 51: 399–413.e7, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM 3rd, et al. : Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177: 1888–1902.e21, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang P, Chen Y, Yong J, Cui Y, Wang R, Wen L, et al. : Dissecting the global dynamic molecular profiles of human fetal kidney development by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cell Rep 24: 3554–3567.e3, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman KA, Bentley MR, Lever JM, Li Z, Crossman DK, Song CJ, et al.: Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies candidate renal resident macrophage gene expression signatures across species. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 767–781, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu J, Akat KM, Sun Z, Zhang W, Schlondorff D, Liu Z, et al.: Single-cell RNA profiling of glomerular cells shows dynamic changes in experimental diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 533–545, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson PC, Wu H, Kirita Y, Uchimura K, Ledru N, Rennke HG, et al.: The single-cell transcriptomic landscape of early human diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 19619–19625, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu H, Malone AF, Donnelly EL, Kirita Y, Uchimura K, Ramakrishnan SM, et al.: Single-cell transcriptomics of a human kidney allograft biopsy specimen defines a diverse inflammatory response. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2069–2080, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craciun FL, Bijol V, Ajay AK, Rao P, Kumar RK, Hutchinson J, et al.: RNA sequencing identifies novel translational biomarkers of kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1702–1713, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Kumar S, Dolzhenko E, Alvarado GF, Guo J, Lu C, et al.: Molecular characterization of the transition from acute to chronic kidney injury following ischemia/reperfusion. JCI Insight 2: e94716, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bao YW, Yuan Y, Chen JH, Lin WQ: Kidney disease models: Tools to identify mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Zool Res 39: 72–86, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonventre JV: Primary proximal tubule injury leads to epithelial cell cycle arrest, fibrosis, vascular rarefaction, and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 4: 39–44, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Clef N, Verhulst A, D’Haese PC, Vervaet BA: Unilateral renal ischemia-reperfusion as a robust model for acute to chronic kidney injury in mice. PLoS One 11: e0152153, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu H, Lai CF, Chang-Panesso M, Humphreys BD: Proximal tubule translational profiling during kidney fibrosis reveals proinflammatory and long noncoding RNA expression patterns with sexual dimorphism. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 23–38, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphreys BD: Mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Annu Rev Physiol 80: 309–326, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L, Besschetnova TY, Brooks CR, Shah JV, Bonventre JV: Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med 16: 535–543, 1p following 143, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H, van Dullemen LFA, Akhtar MZ, Faro ML, Yu Z, Valli A, et al.: Proteo-metabolomics reveals compensation between ischemic and non-injured contralateral kidneys after reperfusion. Sci Rep 8: 8539, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang T, Zhang XM, Tarnawski L, Peleli M, Zhuge Z, Terrando N, et al.: Dietary nitrate attenuates renal ischemia-reperfusion injuries by modulation of immune responses and reduction of oxidative stress. Redox Biol 13: 320–330, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R: Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol 36: 411–420, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu X, Mao Q, Tang Y, Wang L, Chawla R, Pliner HA, et al.: Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat Methods 14: 979–982, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DePasquale EAK, Schnell DJ, Van Camp PJ, Valiente-Alandi I, Blaxall BC, Grimes HL, et al. : DoubletDecon: Deconvoluting doublets from single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Cell Rep 29: 1718–1727.e8, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lizio M, Harshbarger J, Shimoji H, Severin J, Kasukawa T, Sahin S, et al. ; FANTOM consortium : Gateways to the FANTOM5 promoter level mammalian expression atlas. Genome Biol 16: 22, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu Z, Gu L, Eils R, Schlesner M, Brors B: Circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 30: 2811–2812, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Boutros PC: VennDiagram: A package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 35, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lan Y, Kingsley PD, Cho ES, Jiang R: Osr2, a new mouse gene related to Drosophila odd-skipped, exhibits dynamic expression patterns during craniofacial, limb, and kidney development. Mech Dev 107: 175–179, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu J, Liu H, Lan Y, Aronow BJ, Kalinichenko VV, Jiang R: A Shh-Foxf-Fgf18-Shh molecular circuit regulating palate development. PLoS Genet 12: e1005769, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez ME: Combined in situ hybridization/immunohistochemistry (ISH/IH) on free-floating vibratome tissue sections. Bio Protoc 4: e1243, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chihanga T, Ruby HN, Ma Q, Bashir S, Devarajan P, Kennedy MA: NMR-based urine metabolic profiling and immunohistochemistry analysis of nephron changes in a mouse model of hypoxia-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1159–F1173, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schumacher JA, Zhao EJ, Kofron MJ, Sumanas S: Two-color fluorescent in situ hybridization using chromogenic substrates in zebrafish. Biotechniques 57: 254–256, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trinh le A, McCutchen MD, Bonner-Fraser M, Fraser SE, Bumm LA, McCauley DW: Fluorescent in situ hybridization employing the conventional NBT/BCIP chromogenic stain. Biotechniques 42: 756–759, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chhipa RR, Fan Q, Anderson J, Muraleedharan R, Huang Y, Ciraolo G, et al.: AMP kinase promotes glioblastoma bioenergetics and tumour growth. Nat Cell Biol 20: 823–835, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG: ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res 37: W305–W311, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaimal V, Bardes EE, Tabar SC, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ: ToppCluster: A multiple gene list feature analyzer for comparative enrichment clustering and network-based dissection of biological systems. Nucleic Acids Res 38: W96–W102, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonventre JV: Dedifferentiation and proliferation of surviving epithelial cells in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 14[Suppl 1]: S55–S61, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kramann R, Kusaba T, Humphreys BD: Who regenerates the kidney tubule? Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 903–910, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kusaba T, Lalli M, Kramann R, Kobayashi A, Humphreys BD: Differentiated kidney epithelial cells repair injured proximal tubule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 1527–1532, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khreba NA, Abdelsalam M, Wahab AM, Sanad M, Elhelaly R, Adel M, et al.: Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) as an early predictor for acute kidney injury in post-cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in open heart surgery patients. Int J Nephrol 2019: 6265307, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albert C, Albert A, Bellomo R, Kropf S, Devarajan P, Westphal S, et al.: Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin-guided risk assessment for major adverse kidney events after open-heart surgery. Biomarkers Med 12: 975–985, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devarajan P: Review: Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: A troponin-like biomarker for human acute kidney injury. Nephrology (Carlton) 15: 419–428, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singer E, Schrezenmeier EV, Elger A, Seelow ER, Krannich A, Luft FC, et al.: Urinary NGAL-positive acute kidney injury and poor long-term outcomes in hospitalized patients. Kidney Int Rep 1: 114–124, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varnell CD Jr., Goldstein SL, Devarajan P, Basu RK: Impact of near real-time urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin assessment on clinical practice. Kidney Int Rep 2: 1243–1249, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gauer S, Urbschat A, Gretz N, Hoffmann SC, Kränzlin B, Geiger H, et al.: Kidney injury molecule-1 is specifically expressed in cystically-transformed proximal tubules of the PKD/Mhm (cy/+) rat model of polycystic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci 17: 802, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt-Ott KM, Mori K, Li JY, Kalandadze A, Cohen DJ, Devarajan P, et al.: Dual action of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 407–413, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun WY, Bai B, Luo C, Yang K, Li D, Wu D, et al.: Lipocalin-2 derived from adipose tissue mediates aldosterone-induced renal injury. JCI Insight 3: e120196, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basile DP, Anderson MD, Sutton TA: Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury. Compr Physiol 2: 1303–1353, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kudose S, Hoshi M, Jain S, Gaut JP: Renal histopathologic findings associated with severity of clinical acute kidney injury. Am J Surg Pathol 42: 625–635, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, Ko YA, Han SH, Chinga F, et al.: Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med 21: 37–46, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]