Dear Editor,

The Adjunctive Glucocorticoid Therapy in Patients with Septic Shock (ADRENAL) trial investigators reported no treatment-related sex difference in mortality [1], but hydrocortisone treatment was more cost effective in women, compared to men [2]. Previous studies have reported differences in glucocorticoid responsiveness to endotoxin and stress between sexes [3]. To determine sex differences in response to hydrocortisone treatment in patients with septic shock, we conducted a sex-disaggregated analysis of the ADRENAL trial.

Outcomes included the recurrence of shock, the frequency and duration of mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital admissions and the receipt of blood transfusions at 90 days post-randomisation. Health-related quality-of-life was assessed at 6 months post-randomisation. Healthcare resource use and cost data were collected from administrative health records in a subset of patients (N = 1488) at 6 months post-randomisation.

We assessed outcomes in women and men separately using general linear models, logistic regression and Cox regression, respectively reported as mean differences, odds ratios (OR) and hazard ratios (HR). To compare treatment effects in women and men, we assessed differences in mean differences (DMD), ratio of odds ratios (ROR) or ratio of hazard ratios (RHR) and report p values for heterogeneity. We adjusted for clinically relevant variables (age, APACHE II score [4], treatment with renal replacement therapy) and variables that differed between women and men at baseline (Supplementary Methods).

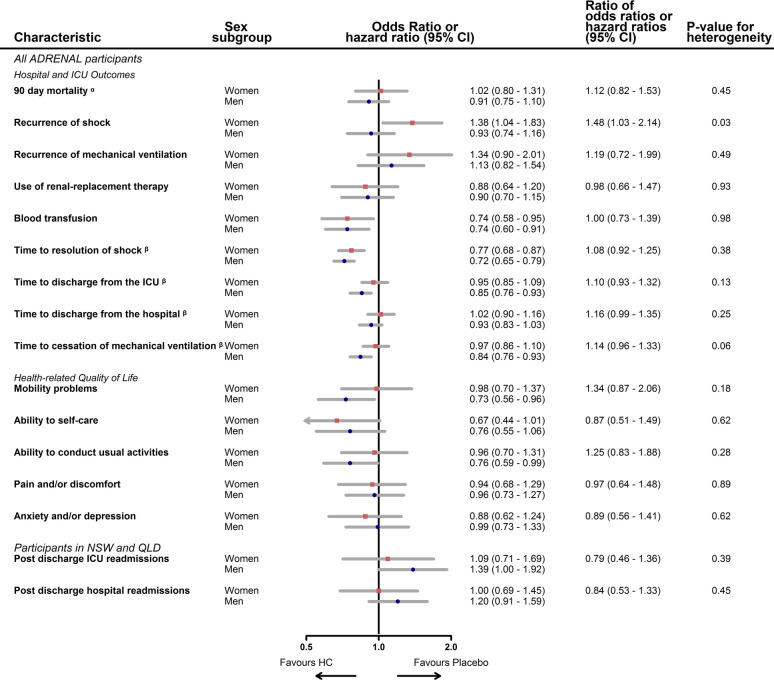

Of 3713 participants, 1454 (39%) were women (Supplementary Figure and Table 1). Hydrocortisone treatment increased the risk of shock recurrence in women but not in men (OR 1.38 versus 0.93; ROR 1.48; 95% CI 1.03, 2.14; p = 0.03). In men, but not in women, hydrocortisone treatment significantly decreased the time to ICU discharge (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.76, 0.93 versus 0.95; 95% CI 0.85, 1.09) and liberation from mechanical ventilation (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.76, 0.93 versus 0.97; 95% CI 0.86, 1.10), although the RHR were not significant (p = 0.13, p = 0.06, respectively). There were no sex differences, women compared to men, in the effect of hydrocortisone treatment on the recurrence of mechanical ventilation (ROR 1.19; 95% CI 0.72, 1.99; p = 0.49), receipt of blood transfusions (ROR 1.0; 95% CI 0.73, 1.39; p = 0.98) or treatment with renal replacement therapy (ROR 0.98; 95% CI 0.66, 1.47; p = 0.93). There were no sex differences in health-related quality-of-life, readmissions to hospital (ROR 0.84; 95% CI 0.53, 1.33; p = 0.44) or costs of hospital visits (DMD -€6527; 95% CI -€15,517, €2,468; p = 0.15) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Impact of hydrocortisone treatment on septic shock outcomes by sex

ICU intensive care unit; NSW New South Wales; QLD Queensland; HC hydrocortisone

a This is a sub-distribution Hazard ratio (sHR) and ratio of sub-distribution Hazard ratio

β In these time to event analyses the reciprocal sHR is displayed, reflecting the impact of hydrocortisone treatment on the outcome expressed in the forest plot. i.e. ratios > 1 favour placebo and < 1 favour hydrocortisone

In 22 trials assessing low-dose corticosteroids in patients with septic shock, corticosteroids significantly reduced the duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay [5]. In our analysis, this was true in men but not in women. Sex-related differences in the clinical presentation, course and outcomes of disease are well recognised in certain medical specialties [6]. The potential for sex differences in critically ill patients with sepsis is starkly illustrated by data from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In the RECOVERY trial that examined the effect of dexamethasone on patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), 36% of the recruited patients were women but only 27% of mechanically ventilated patients were women [7]. This raises important considerations for interpretation of results, where women and men may be more or less likely to acquire severe forms of disease and where treatment effects are dependent on disease severity, true effects in women and men may be masked if sex-disaggregated analyses are not performed in the appropriate subgroups.

The increased recurrence of shock in women treated with hydrocortisone may be due to sex differences in vascular responsiveness. Previous research has found women of reproductive age exhibit increased vascular responsiveness in the normal condition, and have a lower decrease in vascular responsiveness after traumatic shock, compared to men of a similar age [8]. Further research is needed to determine whether our finding is replicated, and explore possible mechanisms.

In the ADRENAL trial, hydrocortisone produced differential effects on some secondary outcomes in women and men. Routine consideration of the impact of trial results separately for women and men, including conducting sex-disaggregated analyses, is appropriate and important in large critical care trials.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Katie Harris, for her artistic skills and Professor Mark Woodward, for his generosity.

ADRENAL sex-disaggregated analysis steering committee: Severine Bompoint: The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia. Cheryl Carcel: The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia; University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Jeremy Cohen: The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia; University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Stephen Jan: The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia; University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. John Myburgh: The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia; University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; St George Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Sanne A.E. Peters: University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands; The George Institute for Global Health, Imperial College London, London, UK. Dorrilyn Rajbhandari: The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia.

Funding

The George Institute for Global Health, Global Women’s Health Program. The Australian College of Critical Care Nurses. NHMRC.

Compliance with Ethical Statement

Conflict of interest

There are no areas of conflict of interest in the study.

Ethical Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The members of the ADRENAL Investigators, sex-disaggregated analysis Steering Committee are listed in the Acknowledgements section.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kelly Thompson, Email: kthompson@georgeinstitute.org.

on behalf of the ADRENAL Investigators, sex-disaggregated analysis Steering Committee:

Severine Bompoint, Cheryl Carcel, Jeremy Cohen, Stephen Jan, John Myburgh, Sanne A. E. Peters, and Dorrilyn Rajbhandari

References

- 1.Venkatesh B, Finfer S, Cohen J, Rajbhandari D, Arabi Y, Bellomo R, et al. Adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):797–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson KJ, Taylor CB, Venkatesh B, Cohen J, Hammond NE, Jan S, et al. The cost-effectiveness of adjunctive corticosteroids for patients with septic shock. Crit Care Resusc. 2020;22(3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/S1441-2772(23)00386-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohleder N, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH, Engel R, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in glucocorticoid sensitivity of proinflammatory cytokine production after psychosocial stress. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(6):966–972. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200111000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–29. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rygård SL, Butler E, Granholm A, Møller MH, Cohen J, Finfer S, et al. Low-dose corticosteroids for adult patients with septic shock: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(7):1003–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millett ERC, Peters SAE, Woodward M. Sex differences in risk factors for myocardial infarction: cohort study of UK Biobank participants. BMJ. 2018;363:k4247. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Group TRC Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. New Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Xiao X, Zhang J, Zhu Y, Hu Y, Zang J, et al. Age and sex differences in vascular responsiveness in healthy and trauma patients: contribution of estrogen receptor-mediated Rho kinase and PKC pathways. Am J Physiol. 2014;306(8):H1105–H1115. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00645.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.