Abstract

Summary

This is a survey study concerning osteoporosis care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Respondents reported that osteoporosis care stagnated and lower quality of care was provided. This leads to the conclusion that standardization of osteoporosis care delivery in situations of crisis is needed.

Purpose

During the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was no guidance of professional societies or guidelines on the organization of osteoporosis care in case of such a crisis, and treatment relied on local ad hoc strategies. Experiences from the current pandemic need to be taken into account for the near future, and therefore, a national multidisciplinary survey was carried out in the Netherlands.

Methods

A survey of 17 questions concerning the continuation of bone mineral density measurements by Dual Energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), outpatient clinic visits, and prescription of medication was sent to physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants working in the field of osteoporosis.

Results

77 respondents finished the questionnaire, of whom 39 (50.6%) reported a decline in DXA-scanning and 36 (46.8%) no scanning at all during the pandemic. There was an increase in remote consultations for both new and control patient visits (n = 48, 62.3%; n = 62, 81.7% respectively). Lower quality of care regarding fracture prevention was reported by more than half of the respondents (n = 44, 57.1%). Treatment with intravenous bisphosphonates and denosumab was delayed according to 35 (45.4%) and 6 (6.3%) of the respondents, respectively.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, osteoporosis care almost completely arrested, especially because of the discontinuation of DXA-scanning and closing of outpatient clinics. More than half of the respondents reported a substantial lower quality of osteoporosis care during the COVID pandemic. To prevent an increase in fracture rates and a decrease in patient motivation, adherence and satisfaction, standardization of osteoporosis care delivery in situations of crisis is needed.

Keywords: Fractures, Osteoporosis, COVID-19, Fracture liaison service

Introduction

Global spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19) has placed health systems under pressure [1]. Due to the large numbers of acute hospital admissions and of patients requiring intensive care, hospitals needed to adapt rapidly [2]. Medical specialists and allied health professionals such as nurses, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) managing chronic diseases, including osteoporosis, were often assigned to other tasks or were asked to switch to remote care. As there has been no guidance of professional societies or guidelines on the organization of osteoporosis care in case of a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, treatment relied on local ad hoc organized strategies. Since osteoporosis care (prevention of fractures) is never acute, there is a fine line between postponing non-urgent elective activity whilst ensuring no harm is done. For example, postponing osteoporosis screening or treatments without losing the window of opportunity after a fracture or treatment window for a denosumab injection [3]. Furthermore, patients themselves might refrain from osteoporosis screening as potential screening candidates are within the COVID-19 ‘risk group’ in terms of age and often co-morbidity and might want to limit the amount of (hospital) visits and risk of contracting the virus.

In the (pre-COVID-19) Dutch guideline for osteoporosis, DXA-scanning as a screening tool for osteoporosis is advised both for patients aged 50 years and older presenting with a fracture and people aged over 60 years old with a high fracture risk [4].

In the aftermath of the pandemic, we are now faced with both postponed referrals and regular care which may have led to more complaints such as fractures. Furthermore, there is a reduction in the number of actual face-to-face contacts in outpatient clinics due to social distancing. Without a vaccine, we might be facing new peaks of COVID-19 infections which could paralyse regular non-emergency (osteoporosis) care again. Thus, current experiences from the pandemic need to be taken into account and translated into practice recommendations including digital health care solutions [5]. For that purpose, firstly, the quality and quantity of osteoporosis care provided during the COVID-19 pandemic must be evaluated. To do so within the Netherlands, a multidisciplinary questionnaire was sent to all health professionals taking care of patients with osteoporosis in the Netherlands during the first COVID-19 peak in the Netherlands between March and May 2020.

Methods

Participants

Physicians, fracture liaison service (FLS) nurses, nurse practitioners (NPs) or physician assistants (PAs) associated with the Dutch Society for Endocrinology, the Working Group Osteoporosis of The Dutch Society for Rheumatology, the Dutch Geriatrics Society, the Dutch Trauma Society and VF&O (Vallen, Fracturen & Osteoporose: the Dutch FLS Nurses/NP/PA association) were asked to participate in this survey. The invitation to participate in the online questionnaire was sent out as a separate e-mail, text message, via Twitter, Facebook or in the societies’ newsletters. A reminder was sent 4 weeks after the first call.

Questionnaire

A short questionnaire was drafted by the study group consisting of three endocrinologists, a rheumatologist, a trauma surgeon, a NP and a geriatrician. An electronic version was created with the program SurveyMonkey Inc® (San Mateo, California).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the respondents’ answers. Analyses were performed for all respondents and separately for physicians and nurses/NPs/PAs. Analyses were performed in SPSS version 25 (SPSS, IBM Corporation). All data are presented as numbers and percentages.

Results

Characteristics of respondents

In total, 85 healthcare providers completed the questionnaire between May 11 and May 26, 2020. Eight questionnaires were excluded because they were not completed by a physician, nurse, NP or PA. Among the 77 remaining participants were 33 (43%) physicians, 29 (38%) nurses, 15 (19.5%) NPs or PAs.

Regular osteoporosis care

Almost all respondents (n = 75, 97.4%) reported a decline in DXA-scanning during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 39 (50.6%) reporting fewer DXA-scans being performed and 36 (46.8%) reporting no DXA-scanning at all. Furthermore, consultation hours changed; as seen in Table 1, more than half of the respondents (n = 48, 62.3%) indicated that new patients were (video) called instead of the regular face-to-face consultation and almost a quarter (n = 18, 23.4%) indicated that appointments with new patient were cancelled. Sixty-two (81.7%) respondents reported that follow-up visits were scheduled as (video)call instead of a consultation at the outpatient clinic and 9 (11.8%) reported complete cancellation of consultations.

Table 1.

Responses regarding an online survey on osteoporosis care during the COVID-19 pandemic among physician and nonphysician professionals in the Netherlands

| Question | Answer | Total (n = 77) Nr (%) | Nonphysicians (n = 44)a Nr (%) | Physicians (n = 33) Nr (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular osteoporosis care | ||||

| DXA possible? | No | 36 (46.8) | 20 (45.5) | 16 (48.5) |

| Less than usual | 39 (50.6) | 22 (50) | 17 (51.5) | |

| No change since COVID-19 | 2 (2.6) | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Consultation new patients | No, all cancelled | 18 (23.4) | 15 (34.1) | 3 (9.1) |

| No newly planned appointments but those planned are continued | 6 (7.8) | 4 (9.1) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Yes, but remote | 48 (62.3) | 21 (47.7) | 27 (81.8) | |

| Yes, no change | 5 (6.5) | 4 (9.1) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Consultation control patients | No, all cancelled | 9 (11.8) | 8 (18.5) | 1 (3.0) |

| No newly planned appointments but those planned are continued | 2 (2.6) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Yes, but remote | 62 (81.7) | 31 (72.1) | 31 (94.0) | |

| Yes, no change | 3 (3.9) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) | ||||

| Patients presenting with fractures at the FLS | Are invited for a consultation as usual | 14 (18.2) | 9 (20.5) | 5 (15.2) |

| Are invited for remote consultation | 14 (18.2) | 6 (13.6) | 8 (24.2) | |

| End up on a waiting list and receive no information on osteoporosis screening. | 24 (31.2) | 14 (31.8) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Are provided with information on osteoporosis screening and receive an accompanying letter that they are called in within 3–4 months. | 13 (16.9) | 7 (15.9) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Are provided with information on osteoporosis screening and receive an accompanying letter that they have to report at the GP for screening. | 1 (1.2) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 11 (14.3) | 7 (15.9) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Management of patients presenting with a hip- or spine fracture during the COVID-19 pandemic | Not | 27 (36.0) | 16 (38.1) | 11 (33.4) |

| Unseen via prescription of oral bisphosphonate (or other medication) | 3 (4.0) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Via the treating orthopedist or traumatologist | 27 (36.0) | 16 (38.1) | 11 (33.4) | |

| After a call or video consultation WITHOUT additional diagnostics | 15 (20.0) | 7 (16.7) | 8 (24.2) | |

| After a call or video consultation WITH additional diagnostics | 18 (24.0) | 10 (23.8) | 8 (24.2) | |

| As usual | 12 (16.0) | 8 (19.0) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Management of patients with a high FRAX® or Garvan score | Not | 30 (41.7) | 19 (48.8) | 11 (33.4) |

| Unseen via prescription of oral bisphosphonate (or other medication) | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Via the treating orthopedist or traumatologist | 30 (41.7) | 19 (48.8) | 11 (33.4) | |

| After a call or video consultation WITHOUT additional diagnostics | 9 (12.5) | 5 (12.8) | 4 (12.1) | |

| After a call or video consultation WITH additional diagnostics | 15 (20.8) | 7 (17.9) | 8 (24.2) | |

| As usual | 16 (22.2) | 8 (20.5) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Patients who are worried to visit the hospital | Consultation remotely but delay start of treatment | 23 (30.7) | 12 (28.6) | 11 (33.3) |

| Consultation delayed for a longer period of time | 18 (24.0) | 12 (28.6) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Consultation remotely and start treatment (with major factures) | 24 (32.0) | 11 (26.2) | 13 (39.4) | |

| You do nothing and leave it to the patient | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Blood sampling elsewhere and plan treatment thereafter | 8 (10.7) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (9.1) | |

| You transfer it to the GP | 2 (2.6) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Treatment with bisphosphonates | ||||

| Continuation of treatment with intravenous Zoledronate (multiple answers could be provided) | I had to discontinue treatment | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| With delay | 35 (45.4) | 16 (39.0) | 19 (52.8) | |

| I transferred patients to oral bisphosphonate of denosumab at my initiative | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.6) | |

| I transferred patients to oral bisphosphonate of denosumab at their request | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| I make more use of home infusions | 5 (6.5) | 1 (24.4) | 4 (11.1) | |

| Unchanged, infusions in hospital are still continued | 15 (19.5) | 12 (29.3) | 3 (8.3) | |

| Unchanged, home infusions are still continued | 20 (26.0) | 12 (29.3) | 8 (22.2) | |

| Treatment with Denosumab | ||||

| Continuation of treatment with Denosumab (multiple answers could be provided) | I had to discontinue treatment | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| With 2–3 weeks delay injections in the hospital I had to discontinue treatment | 6 (6.3) | 3 (5.5) | 3 (7.1) | |

| I transferred patients to oral bisphosphonate at my initiative | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| I transferred patients to oral bisphosphonate at their request | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | |

| I transferred patients to intravenous bisphosphonate at my initiative | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | |

| I let patients self-inject during phone or video consultation | 8 (8.3) | 4 (7.4) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Unchanged, patients receive injections at the hospital or were already used to do self-injection at home | 32 (33.4) | 17 (31.5) | 15 (35.7) | |

| Unchanged, via GP | 47 (49.0) | 30 (55.6) | 17 (40.5) | |

| Quality of osteoporosis care during COVID-19 and reboot of care | ||||

| Lower quality of provided care concerning fracture prevention care than before the COVID-19 pandemic | No | 9 (11.7) | 5 (11.4) | 4 (12.1) |

| Yes | 44 (57.1) | 22 (50.0) | 22 (66.7) | |

| Maybe | 22 (28.6) | 16 (36.4) | 6 (18.2) | |

| I do not know | 2 (2.6) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Estimation of proportion of patients who are not referred | 0–10% | 9 (12.5) | 7 (17.9) | 2 (6.1) |

| 10–25% | 19 (26.4) | 11 (28.2) | 8 (24.2) | |

| 25–50% | 25 (34.7) | 12 (30.8) | 13 (39.4) | |

| 50–75% | 12 (16.7) | 6 (15.4) | 6 (18.2) | |

| >75% | 7 (9.7) | 3 (7.7) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Estimated time until consultation hours like before the COVID-19 pandemic will be resumed | Shorter than 8 weeks | 31 (40.8) | 18 (41.9) | 13 (39.4) |

| I think consultation hours will not be as before the pandemic | 7 (9.2) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (9.0) | |

| Longer than 8 weeks | 24 (31.6) | 9 (20.9) | 15 (45.5) | |

| I do not know | 14 (18.4) | 12 (27.9) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Estimation of proportion of patients not treated adequately in comparison with before the COVID-19 crisis | 0–10% | 15 (20.3) | 9 (22.0) | 6 (18.2) |

| 10–25% | 15 (20.3) | 6 (14.6) | 9 (27.3) | |

| 25–50% | 21 (28.4) | 15 (36.6) | 6 (18.2) | |

| 50–75% | 16 (21.6) | 8 (19.5) | 8 (24.2) | |

| >75% | 7 (9.4) | 3 (7.3) | 4 (12.1) | |

aNurses, nurse practitioners and physician assistants

Fracture liaison service (FLS)

Osteoporosis care for patients who presented with a fracture at the emergency room during the COVID-19 pandemic was affected as well. Fourteen (18.2%) respondents reported that these patients were contacted as usual, whereas another 14 (18.2%) indicated that the patients were screened for risk-factors during an intake before a(n) (call/video) appointment was planned. It is noteworthy that 24 (31.2%) respondents reported that patients were put on a waiting list and were not provided with information concerning osteoporosis screening. Another 13 (16.9%) respondents reported that patients were provided with information on osteoporosis screening and received an accompanying letter that they would be called in within 3–4 months.

Large differences concerning the treatment of patients with a hip or spine fracture were observed. Only a small minority of the respondents reported that osteoporosis care was continued according to the Dutch guideline (n = 12, 16.0%), whereas more than a third (n = 27, 36.0%) indicated that patients with hip or vertebral fractures remained untreated.

Thirty-three respondents (44.0%) reported that a call or video consultation took place, including 15 (20.0%) reporting this was not accompanied by the usual additional diagnostics (DXA scan and laboratory testing).

When patients were screened by taking a medical history and fracture risk assessment according to clinical risk factors, treatment was not always started despite high-risk profiles. With respect to the treatment of patients with a high FRAX® or Garvan score, 30 (41.7%) respondents reported that these patients were not treated. A video (call) consultation was reported by a third (24, 33.3%) but with usual additional diagnostics in only 12.5% (n = 9). Sixteen (22.2%) respondents reported that in patients with a high FRAX® or Garvan score, osteoporosis tests and treatment were done as usual.

It was also needed to deal with patients who were worried about the infection risk in the hospital or outside and did not want to visit the hospital. Delay of consultation was reported by 18 (24.0%) respondents and another 23 (30.7%) respondents informed patients via (video)call but postponed the start of treatment. Twenty-four (32.0%) reported the start of therapy for major fractures after the patients had firstly been informed by telephone or video consultation. A few respondents (n = 8, 10.7%) indicated that blood samples were taken outside the hospital or that osteoporosis care was transferred to the General Practitioner (GP) (n = 2, 2.6%).

Treatment with bisphosphonates

Regarding patients treated with intravenous Zoledronate, 15 (19.5%) respondents reported that treatment could be continued in the hospital and 20 respondents (26.0%) used home administration via a certified nurse. However, treatment was delayed according to 35 (45.4%) of the respondents. Switch of treatment from intravenous treatment to an oral bisphosphonate or Denosumab was only reported by 2 (2.6%) respondents.

Treatment with Denosumab

Forty-seven (49.0%) respondents reported that the subcutaneous injection with Denosumab was already administered via the GP. Thirty-two (33.4%) reported continuation of therapy, either in the hospital or at home by self-injection. Six (6.3%) respondents reported a delay of treatment in the hospital, whereas 8 (8.3%) respondents needed to change the administration of Denosumab acutely as patients needed to self-administer under telephone or video guidance. No patients were switched to other therapies and 1 (1.0%) respondent reported discontinuation of treatment.

Quality of osteoporosis care during COVID-19 and reboot of care

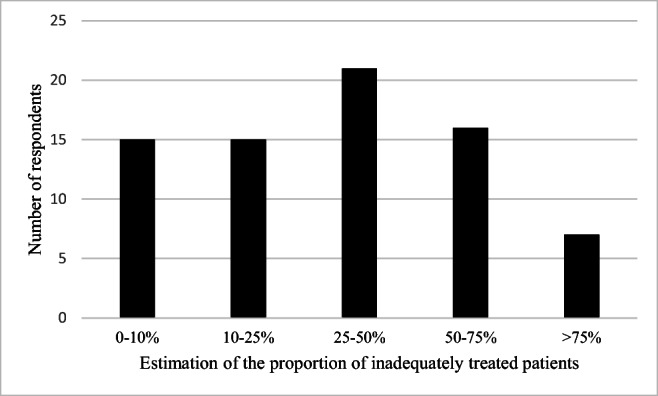

Respondents’ estimations of the proportion of patients that could not be treated adequately during the COVID-19 pandemic varied widely (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Estimation of the proportion of patients not treated adequately for (prevention of) osteoporosis in comparison with before the COVID-19 crisis. Number of respondents (n = 77)

More than half of the respondents (n = 44, 57.1%) felt that their quality of care regarding fracture prevention during the COVID pandemic was lower than before the pandemic.

When respondents were asked to estimate the percentage of patients who were not referred to them, varying rates were reported: 53 (73.6%) estimated that up to half of the patients were not referred to them, whereas 19 (26.4%) thought this was more than 50%.

The majority of the respondents (n = 31, 40.8%) expected to be able to restart the consultation hours as they did before the pandemic within 8 weeks; twenty-four (31.6%) respondents thought this would take longer than 8 weeks and a small proportion (n = 7, 9.2%), thought that the consultation hours would never be like before the pandemic.

Finally, in an open question, respondents were asked whether matters had not yet been addressed in the questionnaire. One issue was addressed by multiple respondents, namely that increase in waiting time at the osteoporosis consulting hours was mostly a result of DXA scans not being performed.

Discussion

We performed this survey on osteoporosis care during the COVID-19 pandemic among Dutch healthcare professionals to map the problems encountered during this period. To date, this is the first national multidisciplinary survey covering this topic. The number of respondents was relatively high (n = 77), given the fact that the Netherlands harbours approximately 70 FLS-es. Another strength of the current study is the fact that the data are derived from practitioners with various professional backgrounds providing osteoporosis care and prevention.

In the Netherlands, prevention and treatment for osteoporosis in new patient arrested and 57.1% of the respondents felt that they were providing care of insufficient quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Especially, the unavailability of DXA-scans resulted in a delay of treatment and screening as well as the closing of the outpatient clinics. Overall, osteoporosis care for follow-up patients could often, with delay and altered consultation hours often, be continued. For new patients who presented with a fracture, however, screening and therapy were delayed and sometimes not performed at all. This is unfavourable, because in the early phase after initial fracture, there is a high risk for new fracture [6].

For known patients with osteoporosis, discontinuation or significant delay of treatment was only seen in patients using intravenous bisphosphonates as they depend on hospital administration. This will, in most patients, not result in any harm if part of regular treatment. However, when given for prevention of rebound after treatment with denosumab this might be the case [7]. This was not specifically addressed in the questionnaire although many respondents indicated continuation of care as usual. Discontinuation or delay was reported for Denosumab-treated patients by 6 (6.3%) respondents, whereas 1 (1.0%) respondent indicated that patients were transferred to bisphosphonates. More precise data on this topic such as rebound fractures or time between injections are lacking as the questionnaire was not designed to address these in detail. Also, we did not cover Romosozumab as this particular agent is not yet approved for reimbursement in the Netherlands.

Until the COVID-19 pandemic, no guideline issuing organization or professional society prepared recommendations on how such a crisis should be handled in terms of ensuring deliverance of osteoporosis care. To date, several position papers have been issued but no real-life data have been presented [8–10].

This study did not observe major problems in continuing drug treatment but did demonstrate major issues regarding fracture prevention and osteoporosis treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic, as reflected by more untreated patients despite high FRAX® or Garvan score, the absence of DXA measurements and cancelled appointments. It seems unlikely that all these patients can be captured after a reboot of the FLS-es although the majority of respondents were rather optimistic about this. Since fragility fracture rates have not dropped during the COVID pandemic, it remains unclear if the suboptimal delivery of osteoporosis care during this substantial period of time will lead to more fractures in the future [11]. We should focus on the follow-up of new and known patients with an indication for treatment, and in general on the incidence rates of fractures in the coming years. For the Netherlands, it might be of use to explore the recently proposed addition to the FRAX® algorithm in the revision of the current guideline for Osteoporosis and fracture prevention in order to get treatment ongoing during a crisis in patients with the highest risk, as the current guideline holds a prominent place for DXA and as such many healthcare providers will not easily go pass this advice [12].

Alternative modes for care delivery were employed by respondents, such as telephone contacts and video consultations. In addition, some interventions, like subcutaneous injections were transferred to the GP. From the results of the current questionnaire, it remains unclear how large the proportion of patients is that did not receive denosumab, since no information was gathered on injections given by GPs. In order to evaluate whether the transfer of care was successful, it is important that patients should be registered appropriately so that they can be contacted after the crisis. Furthermore, it points out that a good communication system with the GP is an overlooked problem, at least in the Netherlands. With telemedicine being introduced in many more patients than before the COVID-19 pandemic, more studies on the quality of alternatives methods of provision of osteoporosis care should be performed, since the literature on the effectiveness of innovative modes of delivery is scarce [13]. Moreover, we observed differences between professions, as nonphysicians less frequently reported continuation of consultation hours via (video) call for new patients than physicians (n = 21, 47.7% vs n = 27, 81.8%, respectively) and more often reported cancellation of appointments with new patients (n = 15, 34.1% versus n = 3, 9.1%, respectively). As for control patients, the same trend was observed.

Unlike we expected, no striking differences in survey answers were observed between respondents from the southern provinces of the Netherlands, where COVID-19 incidence rates were higher, when compared to the other provinces.

This study has a number of limitations. As it was designed to address a multidisciplinary group in a rapid way, we restricted the questions to 17 so that the survey would take 5–6 min maximum to complete as we wanted to get as many responses as possible. The current number of respondents is sufficient to get an overview of changes of osteoporosis care in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, there might be selection bias, such as health professionals experiencing problems in care or professionals more dedicated to osteoporosis care being more likely to fill in the questionnaire. However, due to the high number of respondents and the variation in answers, we consider responses truly reflecting the situation with osteoporosis care.

The COVID-19 pandemic has initiated changes in our management of chronic, not acute care, which includes osteoporosis. Not only in the Netherlands but also globally, this is observed; the online FRAX tool has been accessed 58% less when compared to the previous year [14]. During the acute phase of the pandemic, we have postponed non-urgent elective consultations, tests and even therapeutic interventions. As we now enter the chronic phase of COVID-19, we need to make plans to mitigate the potential adverse effects and prepare a solid plan for future COVID-19 or other outbreaks locally or nationally. This can be done in many ways but starts by making plans for continuing outpatient clinics physically or remotely and ensuring basic screening and treatments. Furthermore, we should focus on better communication about treatments (starting and continuing) with patients, caregivers and GPs in order to enable them to take control in their (remote) treatments, especially as recent reports show worsened outcomes of patients with hip fractures and COVID-19 infections [15, 16]. Without active planning of this chronic but important care, we might face an increase in fracture rates and a decrease in patient compliance and satisfaction in the near future.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the members of the BONE group of the Dutch Society for Endocrinology, the Osteoporosis working group of the Dutch Society for Rheumatology, the Dutch Nurse/PA/NP society for osteoporosis and fracture prevention (Vallen, Fracturen & Osteoporose), the Dutch Society for Geriatrics and the Dutch Trauma Society for their responses.

Authors’ contributions

JJMP: analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

PvdB: composed the survey and commented on the manuscript.

JvdB: composed the survey and commented on the manuscript.

MHEV: composed the survey and commented on the manuscript.

GdK: commented on the manuscript.

WFL: composed the survey and commented on the manuscript.

EMW: commented on the manuscript.

MCZ: composed the survey and commented on the manuscript.

NMAD: designed the study, composed the survey, writing of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

JJMP: none. PvdB: none. JvdB: received in the past honoraria for lectures or advice from Amgen, Eli-Lilly and UCB and research funding by Eli-Lilly and Amgen. MHEV: received in the past honoraria for lectures or advice from Amgen, Eli-Lilly and UCB. GdK: none. WFL: received in the past honoraria for lectures or advice from Amgen, Eli-Lilly and UCB and research funding by Eli-Lilly and Amgen. EMW: received in the past honoraria for lectures or advice from Amgen, Shire and Lilly. MCZ: received in the past honoraria for lectures or advice from Amgen, Kyowa Kirin, Eli-Lilly, Shire, and UCB. NMAD: received in the past honoraria for lectures or advice from Amgen, Kyowa Kirin, Shire and UCB and research funding by UCB.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Jan 30] Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, Leung GM, Oshitani H, Fukuda K, Cook AR, Hsu LY, Shibuya K, Heymann D. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10227):848–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsourdi E, Langdahl B, Cohen-Solal M, Aubry-Rozier B, Eriksen EF, Guañabens N, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Ralston SH, Eastell R, Zillikens MC. Discontinuation of Denosumab therapy for osteoporosis: a systematic review and position statement by ECTS. Bone. 2017;105:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutch Guideline of osteoporosis and fracture prevention (Osteoporose en fractuurpreventie). https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/osteoporose_en_fractuurpreventie/osteoporose_en_fractuurpreventie_-_startpagina.html. Accessed 5 Nov 2020

- 5.Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Odén A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, de Laet C, Jönsson B. Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(3):175–179. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Makras P, Aubry-Rozier B, Kaouri S, Lamy O (2017) Clinical features of 24 patients with rebound-associated vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation: systematic review and additional cases. J Bone Miner Res 32(6):1291–1296 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Girgis CM, Clifton-Bligh RJ. Osteoporosis in the age of COVID-19. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(7):1189–1191. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05413-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gittoes NJ, Criseno S, Appelman-Dijkstra NM, Bollerslev J, Canalis E, Rejnmark L, Hassan-Smith Z. Endocrinology in the time of COVID-19: management of calcium metabolic disorders and osteoporosis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183(2):G57–G65. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu EW, Tsourdi E, Clarke BL, Bauer DC, Drake MT. Osteoporosis Management in the Era of COVID-19. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(6):1009–1013. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar Jain V, Lal H, Kumar Patralekh M, Vaishya R. Fracture management during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(Suppl 4):S431–S441. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanis JA, Harvey NC, McCloskey E, Bruyère O, Veronese N, Lorentzon M, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Adib G, al-Daghri N, Campusano C, Chandran M, Dawson-Hughes B, Javaid K, Jiwa F, Johansson H, Lee JK, Liu E, Messina D, Mkinsi O, Pinto D, Prieto-Alhambra D, Saag K, Xia W, Zakraoui L, Reginster JY. Algorithm for the management of patients at low, high and very high risk of osteoporotic fractures [published correction appears in Osteoporos Int. 2020 Apr;31(4):797-798] Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05176-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paskins Z, Crawford-Manning F, Bullock L, Jinks C. Identifying and managing osteoporosis before and after COVID-19: rise of the remote consultation? Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(9):1629–1632. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05465-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCloskey EV, Harvey NC, Johansson H et al (2020) Global impact of COVID-19 on non-communicable disease management: descriptive analysis of access to FRAX fracture risk online tool for prevention of osteoporotic fractures [published online ahead of print, 2020 Oct 14]. Osteoporos Int 1–8. 10.1007/s00198-020-05542-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Cheung ZB, Forsh DA. Early outcomes after hip fracture surgery in COVID-19 patients in New York City. J Orthop. 2020;21:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall AJ, Clement ND, Farrow L, IMPACT-Scot Study Group. MacLullich AMJ, Dall GF, Scott CEH, Jenkins PJ, White TO, Duckworth AD. IMPACT-Scot report on COVID-19 and hip fractures a multicentre study assessing mortality, predictors of early SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the effects of social lockdown on epidemiology. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B(8):2049–4394. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B9.BJJ-2020-1100.R1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]