Abstract

Novel COVID-19 is having far-reaching consequences worldwide. Security and security management are not immune from this influence. Building on the scientific literature, this article explores the mixed impact of this unexpected macro-level phenomenon and its consequences on violent extremism and terrorism in the West, in the short and in the medium to long term. The paper looks at the influence on extremist beliefs and attitudes and, moreover, it examines the effects on extremist behaviors, with an emphasis on terrorist activities, drawing on a model of terrorist attack cycle. The COVID-19 pandemic can be interpreted as a global natural experiment that offers insight into causal processes, in the interplay among societal, group, and individual factors.

Keywords: Violent extremism, Terrorism, COVID-19, Propaganda, Counterterrorism, Security

Novel COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019), first identified in China in December 2019, has officially resulted in a pandemic since March 2020. As is well known, it is having far-reaching consequences across the world: virtually every aspect of social life at national and international level has been affected by this unexpected macro-level phenomenon. Security and security management are not immune from this influence. Building on the existing literature, this article intends to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the risk of multiple waves over time, and its consequences on violent extremism and terrorism in the West (Europe, North America, and Australasia), in the short and in the medium to long term.

Before starting this exploration, a definitional clarification is required. Both violent extremism and terrorism are elusive and controversial concepts (see, for example, Schmid 2011; Berger 2018). For the purposes of this article, violent extremism refers to a spectrum of beliefs and values associated with the will to shape the political and social order, usually in the sense of a radical change, by unconditionally using violence against an out-group.1 Terrorism is instead a political strategy used by a non-state actor (Merari 1993).2 An act of terrorism can be interpreted as a deliberate act of violence against persons, committed by one or more individuals motivated by ideological motives, with the intention to coerce, intimidate, or convey some other message to an audience larger than the immediate victims violence represents (Vidino et al. 2017, p. 38).

Clearly, only a minority of violent extremists are actually engaged in terrorist violence. As McCauley and Moskalenko (2008, p. 417) noted, “[b]ecause terrorists are few in relation to all those who share their beliefs and feelings, the terrorists may be thought of as the apex of a pyramid. The base of the pyramid is composed of all who sympathize with the goals the terrorists say they are fighting for. […] From base to apex, higher levels of the pyramid are associated with decreased numbers but increased radicalization of beliefs, feelings, and behaviors.”

The article is divided into two main sections. The first section takes into account extremist beliefs and attitudes, examining both group pull factors and individual push factors. On the one hand, in the short time, the COVID-19 pandemic has led violent extremists to adjust their propaganda to the new context. For example, jihadists presented the virus as a divine punishment against disbelievers and right-wing extremists used the crisis to scapegoat populations or social categories accused of being responsible for the infection. On the other hand, the pandemic and its consequences could contribute to produce negative states of mind and grievances, associated to a sense of injustice, that tend to underlie various forms of violent extremism. The second section looks at extremist behaviors, with an emphasis on terrorist activities. Building on a model of “terrorist attack cycle” (Stratfor 2016), this part explores how the current pandemic can affect seven different phases of terrorist activities, from target selection to exploitation of violence, together with counterterrorism responses.

The article aims to suggest potential causal relations, in the interplay among three levels of analysis: the “macro” level (concerning societal factors), the “micro” level (concerning individual traits), and the “meso” level (concerning group characteristics). The discussion on these complex phenomena does not purport to be complete and exhaustive, nor could it be. At the time of writing, the actual evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences are not yet entirely clear. The main goal of this exploratory contribution is therefore to suggest possible trajectories in the evolution of violent extremism and terrorism in the West, drawing on the literature in this field.

Extremist beliefs and attitudes: from group propaganda to individual grievances

This section explores the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on extremist beliefs and attitudes, drawing on primary and secondary sources. It examines both group pull factors that support the appeal of violent extremism, on the one hand, and individual push factors that drive people to violent extremism, on the other hand (see Schmid 2013).

As regard “pull factors,” in the short term, violent extremists have quickly sought to exploit the current pandemic for propaganda purposes, at the meso level. In this field, jihadists, right-wing extremists, and left-wing and anarchist extremists have been highly responsive to the spread of the novel coronavirus infection.

Jihadists have attempted to promptly incorporate this new unexpected phenomenon into their usual narratives (cf. Halverson et al. 2011; Schmid 2015; Braddock and Horgan 2016; Mahood and Rane 2017) and themes, with different, sometimes even contradictory rhetorical strategies. As regard official propaganda produced and released by established organizations, the so-called Islamic State (IS), arguably the most influential jihadist organization in our age, initially adopted a wait-and-see approach: in particular, in a lengthy article published in Issue 220 of its Arabic-language weekly bulletin al-Naba’, published on February 06, 2020, IS cautioned that it was not appropriate to come to the conclusion that the spread of the virus was a punishment from God against China for persecution of Muslim Uyghurs (Al-Tamimi 2020). However, as Europe and Iran became epicenters of the disease around late February 2020, IS, as well as other jihadist organizations, presented it as a divine punishment against the disbelievers (and consequently a help for the “true” believers). They also encouraged to take advantage of this opportunity to attack enemies. For example, in the editorial of Issue 224 of al-Naba’ (5 March 2020), entitled “The Crusaders’ worst nightmare,” IS argued that its members and supporters had to exploit the adversaries’ weaknesses and show no mercy in trying to launch attacks (ICG 2020; Al-Tamimi 2020). The jihadist narrative changed again when the pandemic started to affect Muslim-majority countries: then, several jihadists, including armed groups such as IS and al-Qaeda, began saying that COVID-19 was sent as a wakeup call to humanity, including Muslims, to “return to God.” Al-Qaeda, for example, in a comment released on March 31, 2020, stated that the spread of the virus among Muslims was the result of their laxity in observing Islam (al-Lami 2020). Interestingly, in their official propaganda, jihadist organizations have thus far shown little interest in conspiracy theories. On the contrary, in Issue 227 of al-Naba’ (March 26, 2020), IS even ridiculed “ignorant” theories about the US or Chinese governments’ involvement in developing the virus. In doing so, IS wanted to assert that God alone, rather than man, controls this type of events (al-Lami 2020).

By contrast, in unofficial jihadist discourse, produced by sympathizers, particularly on the Web, conspiracy theories are not uncommon. In fact, several IS supporters have claimed that the virus was created in a lab or as part of a “Zionist” plot. In an interesting recent contribution, Daymon and Criezis (2020) analyzed pro-IS content produced in various languages by decentralized sympathizers on social networking and messaging platforms between January and April 2020. The authors found that conspiracies were among the most widespread narratives and themes, together with news updates on coronavirus by country, references to divine punishment, religious support and resources (such as discussions on prayer at home, reminders of faith, and references to religious scriptures), and “vindictive” content.

For their part, right-wing extremists, such as white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and neo-Fascists (cf. Bjørgo and Ravndal 2019), have promptly reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic with a range of narratives and themes (Comerford and Davey 2020; see also McNeil-Willson 2020). In general, their propaganda has opportunistically used the current pandemic to challenge authority, to mobilize sympathizers, sometimes even explicitly inciting violence, and to lash out against their usual enemies (Marone 2020). In particular, right-wing extremists have used COVID-19 to scapegoat populations or social categories accused of being responsible for the infection: for example, Chinese nationals or people of Asian origin, but also Jews and other religious or ethnic minority groups, or migrants (McNeil-Willson 2020, pp. 12–15), or even well-known “globalist” tycoons such as Bill Gates or George Soros. They have also adjusted their anti-government rhetoric to suggest that the state is using the pandemic as an opportunity to infringe on civil liberties (Comerford and Davey 2020; McNeil-Willson 2020, pp. 18–19).

In addition, right-wing extremists have often amplified a variety of conspiracy theories relating to the virus. Once again, in general, it is possible to find a connection between political extremism and conspiracy theories (see, for example, Van Prooijen et al. 2015). For example, some right-wing extremists have claimed that 5G telecommunication technology, which is currently being deployed in many countries in the West, would be the real cause of the Coronavirus disease. Furthermore, dozens of mobile phone masts have been damaged in the United Kingdom and in other Western countries since the outbreak of the Coronavirus emergency. While the actual perpetrators are not always known, there is no doubt that these acts have been at least welcomed and even encouraged by extreme-right activists, especially on online platforms, such as Telegram (Meleagrou-Hitchens and Crawford 2020). Furthermore, recent research has documented that belief in 5G COVID-19 conspiracy theories is positively associated with these violent responses, mediated by anger, especially for individuals highest in paranoia (Jolley and Paterson 2020, p. 636).

In comparison with jihadists and right-wing extremists, the reaction from left-wing and anarchist extremists has been less intense and dramatic (cf. Wither 2020) whilst remaining relevant. These groups and militants have seen in the current emergency a further opportunity to challenge political authority, especially in a phase of concentration of government power, and capitalism, especially when a seeming trade-off between public health and business has emerged in several Western countries (Marone 2020). In particular, several extremist publishers have authored texts of analysis and critique, including members of the global insurrectionary Informal Anarchist Federation (FAI) (see Marone 2015) and of far-left Greek armed group Revolutionary Struggle (see Kassimeris 2011). Online anarchist hubs have even reported on “clandestine, militant actions, noting that closures and quarantine are likely contributing to the motives of saboteurs and vandals” (Loadenthal 2020). For example, an official publication released by Belgium’s civilian intelligence agency VSSE in April 2020 noted that a “leftist anarchistic website […] launched a call to make use of the COVID-19 outbreak to commit acts of violence against police and penitentiary staff and to damage telecom infrastructure in order to inflict as much damage as possible to our society” (VSSE 2020, p. 7, emphasis in the original). Furthermore, insurrectionary anarchist groups claimed responsibility for acts of violence on property, mentioning the health crisis: for example, a Greek group set fire to vehicles in Thessaloniki in April 2020 (Loadenthal 2020).

In general, it is important to stress that in several Western countries, restrictions and difficulties in the movement of people have pushed several individuals to spend even more time on the internet (in particular, working from home or attending school remotely), at times in conditions of face-to-face isolation. This situation can have the effect of increasing the risks of online radicalization (e.g., see Malik 2020). In fact, it is well known that the internet can represent a fertile ground for violent extremism. The level of anonymity on the Web tends to create a disinhibition effect that can, in turn, foster increased hostility and polarization. Additionally, the attendance of online extremist channels can facilitate the isolation of the user from the surrounding context and the inclusion in closed “echo chambers” of like-minded people in which extremist beliefs and attitudes can be further reinforced and amplified (see, among others, Meleagrou-Hitchens et al. 2017). Interestingly, the first available analyses have shown an increase in extreme-right search traffic in the United States and in Canada during the pandemic (Moonshot 2020a, b).

When it comes to individual “push factors,” it can be assumed that in the West the COVID-19 emergency and its consequences could breed or exacerbate states of mind and grievances that tend to underlie various forms of violent extremism, at the micro level. In the short term, in the West the pandemic has already resulted in losses and traumas (such as the death of hundreds of thousands of people), disruption of daily life habits (including the risk of face-to-face isolation), psychological distress in several individuals, and, in general, high levels of uncertainty in different fields. As experts have noted, short-term psychological effects of the pandemic have included “aspecific and uncontrolled fears,” anxiety, frustration, boredom, and a pervasive sense of loneliness (e.g., Serafini et al. 2020, p. 2).

Furthermore, in the medium and long term, the economic, social, political, and cultural consequences of the pandemic at the macro level could create or reinforce a range of negative states of mind (see Koomen and Van Der Pligt 2015), including internally oriented emotions (such as fear) and, even more, externally oriented emotions (such as contempt, anger, resentment, and hate) (van den Bos 2020, p. 577), that could make a greater number of people more susceptible to extremist narratives, at the micro level. On an individual level, personal traumas, such as job loss, could produce uncertainty and distress.

In the existing literature, there are many indications that radicalization into violent extremism may be facilitated by high levels of uncertainty (in particular, Hogg and Blaylock 2012), actual or perceived personal losses (e.g., McCauley and Moskalenko 2011), frustration (e.g., Gambetta and Hertog 2017) and, at least according to some scholars (Pyszczynski et al. 2006), reminders of death; all these factors can be associated with the pandemic and its consequences (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 61). In general, as many scholars have pointed out, absolute deprivation, in terms of objective lack of resources and status, could be less relevant than relative deprivation, mediated by expectations and comparisons with one’s reference group (Gurr 1970).

Such negative states of mind can contribute to the emergence of relevant personal grievances, associated with an additional feeling of unfair treatment (see, among others, Van den Bos 2020). Research in violent extremism has argued that personal grievances are a common element in radicalization (e.g., Desmarais et al. 2017, p. 191), to such an extent that a number of interpretations include their adoption as a necessary element of violent extremism (Berger 2018, p. 127). For example, the oft-cited models proposed by McCauley and Moskalenko (2008, 2011, chapter 2) and by Hafez and Mullins (2015, pp. 961–964) include grievances as a key mechanism.

Clearly, not all personal grievances lead to violent extremism. Here, at the meso level, the role of extremist groups and organizations is often crucial. In general, they undertake to insert manifest or latent grievances in extremist narratives that construct a presumed crisis as a situation of unbearable injustice caused by a blameworthy out-group. In this respect, the pandemic and its negative consequences could offer ideal circumstances to step up radicalization and recruitment efforts. In fact, it is hard to think that such adverse conditions may not represent a potential opportunity for extremist groups that aim to offer their radical solution to a condition of presumed injustice. Furthermore, extremist groups are often well-structured groups with clear boundaries in which members interact and share group attributes and goals and have a common fate; these sort of groups (so-called “highly entitative groups”) are particularly effective at reducing personal uncertainty. Personal uncertainty, in turn, tends to increase group identification (Hogg and Blaylock 2012; van den Bos 2020, pp. 574–575).

Needless to say, in a given context, not all individuals will be equally vulnerable to the risk of radicalization into violent extremism. First, not all people have significant grievances, associated with a strong sense of injustice. Second, even though all extremists have grievances, not all people with grievances become extremists. Personal grievances have to be framed in political / ideological terms; hence the relevance of extremist propaganda and proselytism. In particular, following a well-known analytical framework from social movement studies (in particular, Benford and Snow 2000; see also Snow and Byrd 2007), three “core framing tasks” can be identified: “diagnostic” framing, concerning the construction of the supposed problem as an existential threat and the attribution of blame to the out-group, “prognostic” framing, concerning the articulation of a solution for change, and “motivational” framing, concerning the provision of motivations and incentives for action. As Berger (2018, p. 131) recently summarized, “[i]n essence, extremist ideologies weld grievances to a system of meaning in which they become both universal and personal, while insisting on hostile action to resolve the conflict. This toxic worldview can then be applied to help mobilize hostile action against specific individuals or entities associated with an out-group.”

In this process of radicalization into violent extremism, in addition to personal predisposing factors at the micro level (such as socio-demographic characteristics, psychological traits, or biographical experiences), the role of social networks at the meso level may be crucial. In fact, many studies have confirmed that social ties, including pre-existing personal relationships (such as kinship and friendship bonds) (e.g., Hafez 2016; Marone 2017), often play a major part (among others, Sageman 2004; della Porta 2013). On many occasions, “radicalization is, generally speaking, ‘about who you know’. It is a group phenomenon, which takes place among small clusters of individuals who influence and support each other” (Vidino et al. 2017, p. 83).

Against this background, environments and situations characterized by high levels of vulnerability could pose further risks (Marone 2020). For example, special attention should be paid to prisons, traditionally a crucial place for potential radicalization processes (among others, Silke 2014). Extremist messages can find a fertile ground in this special environment, which is already characterized by serious personal grievances, conditions of fragility and marginalization, and rigid institutional constraints and limitations. Furthermore, in this phase, prisoners have to deal with the fact that measures against the spread of infection, such as interpersonal distancing, may be, to say the least, complex.

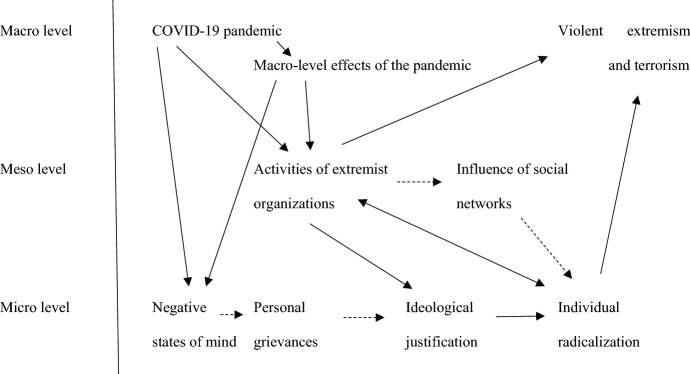

The diagram (Fig. 1) illustrates the dynamics outlined in this section, in the interplay among macro (societal), meso (group), and micro (individual) levels of analysis. This stylized framework should be understood merely as a preliminary analytical construct designed to explore the potential impact of the pandemic on violent extremism in the West. Actually, radicalization into violent extremism and terrorism tends to be a complex, multifactor, and nonlinear process (e.g., Hafez and Mullins 2015). In short, analytically, the pandemic at the macro level can have a relevant direct or indirect impact on both extremist groups and organizations at the meso level (for example, on their propaganda or on their operational skills) and individuals at the micro level (for example, on their personal states of mind). These meso-level and micro-level dynamics can in turn significantly influence macro-level developments, particularly, in terms of collective phenomena of violent extremism and terrorism.

Fig. 1.

A stylized framework of the impact of the COVID-19 on violent extremism and terrorism based on the interplay among the macro (societal), meso (group), and micro (individual) levels of analysis

Negative states of mind and grievances due to the COVID-19 crisis could push some individuals or groups of people to threaten or even carry out acts of politically motivated violence, even without a clear reference to a specific ideology. For example, on April 1, 2020, in Los Angeles, a train engineer, Eduardo M., was arrested for attempting to crash a locomotive into a military ship docked at the city’s port to assist the population during the pandemic. As the 44-year-old man confessed to the police, he believed the ship had suspicious purposes, even linked to an imaginary secret plan to bring down the national government during the emergency. Fortunately, no one was injured in the incident (US Department of Justice 2020b). This episode confirms that conspiracy theories may not always be harmless (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 62).

A case occurred in Canada is not less interesting. On July 2, 2020, Corey H., a 46-year-old military reservist, stormed the grounds of Rideau Hall (the official residence of the General Governor of Canada and the place where Prime Minister Justin Trudeau lives), in Ottawa, with multiple firearms. According to the information currently available (Stephenson and Connolly 2020), in a two-page letter, Corey H. explained that he had recently lost work and had financial issues. He also “described his fears that he would not be able to get back on his feet once the pandemic ends.” Here we can find negative feelings related to the COVID-19 pandemic (uncertainty and fear) that apparently exacerbate personal traumatic events (the loss of work and financial issues). Such strictly personal aspects are then combined with political/ideological motivations, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Corey H., in fact, wrote in the letter that he “feared the suspension of Parliament due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic was creating a lack of accountability for the government.” Furthermore, the man “feared the country was turning into a communist dictatorship under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.” At the time of writing, there are indications that Corey H. was interested in conspiracy theories (Ling 2020), including the well-known far-right QAnon conspiracy theory (see Amarasingam and Argentino 2020), but no evidence has emerged to suggest that he was a member of any extremist group (Thompson and Brewster 2020). However, existing research shows that even lone actors may be in touch with like-minded individuals online and/or offline or, at least, they may be embedded in, and motivated by, the rhetoric of larger extremists movements (Berntzen and Sandberg 2014, p. 760 ff.).

Extremist behaviors: terrorist activities

This section explores the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on extremist behaviors, with an emphasis on terrorist violence. In general, it is worth recalling that existing research has shown that committing an act of terrorism is a purposeful behavior that is usually guided by rationality. Terrorists tend to make cost–benefit decisions that are utility maximizing and likely to increase their probability of success, in a similar way as ordinary criminals do (Marchment and Gill 2020, p. 2).

First of all, restrictions imposed by the pandemic could push violent extremists to pay more attention to cyberterrorism.3 In the cognate field of cybercrime, for example, preliminary analyses found out an increase in the number of incidents in Western countries during the months with the strictest lockdown restrictions, as an effect of the displacement of crime opportunities from physical to online environments (Buil-Gil et al. 2020). However, in general, according to various scholars (e.g., Bernard 2017; see also Borghard and Lonergan 2019), so far terrorist organizations have shown neither the actual intention nor the capability to launch genuine cyberattacks that can result in physical harm to people. On the one hand, the intention to use these methods is not well documented (e.g., Bernard 2017). On the other hand, the undeniable experiences and skills of a few terrorist organizations, such as IS (e.g., Bernard 2017; see also Alexander and Clifford 2019), in the sphere of online propaganda and communication do not necessarily transfer to the ability to launch destructive cyberattacks (Marone 2019, p. 13). Nevertheless, it cannot be excluded that the constraints associated with the current pandemic may potentially lead aspiring terrorists to re-evaluate this option.

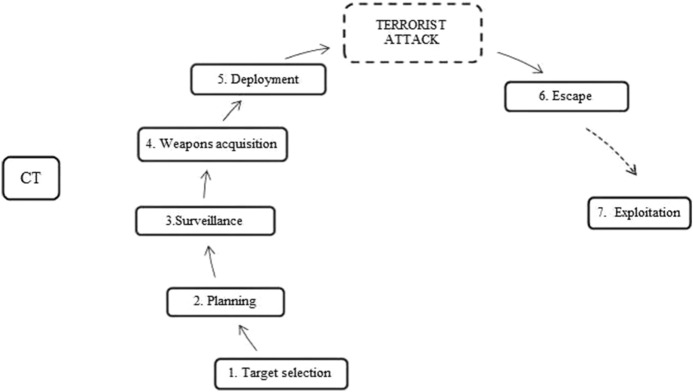

When it comes to conventional terrorism in the physical world, drawing on a model of “terrorist attack cycle” outlined by Stratfor (2016, p. 2), we can analytically distinguish seven main phases of terrorist violence: target selection, planning, surveillance, weapons acquisition, deployment, escape, and exploitation. In addition, we also take into account the role of counterterrorism (CT) (Fig. 2). Clearly, this model is an analytical construct: not all real terrorist attacks necessarily present all these seven phases, in this exact order. The section explores the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on each phase, especially in terms of short-term direct effects. In fact, since the pandemic and restrictive measures might have impact on terrorist activities and their modus operandi, it is important to think about such effects, to be able to outline future scenarios. The following considerations can generally be applied to terrorist acts inspired by different ideologies.

Fig. 2.

The seven phases of terrorist activities.

Source: author’s re-elaboration from Stratfor (2016)

Target selection

In general, terrorists tend to actively select areas and targets (e.g., Drake 1998; de la Calle and Sánchez-Cuenca 2006; Asal et al. 2009) in a way that minimizes effort and risks and maximizes rewards (Marchment and Gill 2020, p. 2). In the short term, the pandemic could alter this process (see Stern et al. 2020). As is well known, in recent years, jihadists, right-wing extremists, and left-wing and anarchist extremists have not hesitated to plan and carry out attacks on the civilian population (from the November 2015 attacks in Paris to the August 2019 mass shooting in El Paso, Texas, to mention just two examples). Against this background, in principle, countries under a national lockdown or with serious restrictions could offer a smaller number of easy targets for indiscriminate violence, particularly in closed public places or on public transport: large gatherings for concerts, sporting events, or other live performances (as in the jihadist attacks at the Bataclan, Paris, on November 13, 2015 and at the Manchester Arena on May 22, 2017), might be impossible, at least during the most acute phase of the coronavirus infection. Nevertheless, terrorist targets are of course still available, especially for small-scale attacks by lone actors or small cells. Consider, for example, the suspected jihadist attack in Romans-sur-Isère, France, on April 4, 2020, under the national lockdown: on that occasion, a 33-year-old refugee stabbed a few people, including two customers who were waiting in line outside a bakery; in total, two people died and five were injured (Marone 2020).

On the other hand, hospitals and medical personnel might become targets of terrorist violence. For example, on March 24, 2020, in the United States, a far-right sympathizer already known to authorities was shot dead during an FBI operation to arrest him on charges of planning an attack precisely on a hospital in the Kansas City area. Interestingly, the man had reportedly already been plotting an attack, but changed his target and his timing following the outbreak of COVID-19, because the medical center apparently could offer more casualties (BBC 2020). This type of threat is also perceived in Europe (Dearden 2020; Rising 2020). In general, it is worth mentioning that hospitals have already been targets of terrorism on many occasions. For example, according to Ganor and Halperin Wernli (2013), there were 103 terrorist attacks on hospitals in the period 1981–2013 in 43 countries, resulting in 775 casualties (see also Fischbacher-Smith and Fischbacher-Smith 2013).

Moreover, especially in countries with severe restrictions on the movement of ordinary citizens, there might be an increased focus on members of law enforcement. In this regard, it can be recalled that in France three police officers were injured when a driver deliberately rammed his car into them in the town of Colombes, on April 27, 2020, during the lockdown period. The perpetrator, a 29-year-old French citizen who was arrested on the spot, had pledged allegiance to the so-called Islamic State (Marone 2020).

Planning

All terrorist attacks require a stage of preparation of varying length and complexity (e.g., Gill et al. 2020; Torres-Soriano 2019). The pandemic can offer both constraints and opportunities for terrorist planners. As regard constraints, planning may require movement of people involved in the operation, for operational face-to-face meetings, the acquisition of weapons or other tasks, at least in the case of complex terrorist attacks. In the short term, the pandemic could make these movements more complicated and less frequent. In fact, apart from suicide bombers and highly motivated operatives, a part of the individuals involved in terrorist operations might be reluctant to expose themselves unnecessarily to infection (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 60). In any case, even committed violent extremists could be stopped by official movement restrictions. A potential real-world example of this scenario can be seen in the arrest of a Pakistani doctor, Muhammad Masood, in the United States, in March 2020. Between January and March 2020, this 28-year-old man made several extremist statements to others, including pledging his allegiance to IS’s leader, expressing his desire to travel to Syria to fight for the jihadist organization, and even conducting lone actor terrorist attacks in the US. In February 2020, Masood purchased a plane ticket from Chicago to Amman, Jordan, and from there he planned to travel to Syria. However, on March 16, 2020, his travel plans changed precisely because Jordan closed its borders to incoming travel due to the coronavirus emergency. Masood made a new plan to fly from Minneapolis to Los Angeles to meet up with an individual who he believed would assist him with travel via cargo ship to deliver him to IS territory. He was arrested on 19 March at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport for attempting to provide material support to IS (US Department of Justice 2020a).

When it comes to opportunities, in the short term, terrorists might utilize this unwanted “downtime” to plan and coordinate future attacks. This could include a wide array of hostile surveillance activities on the Web or through other electronic tools or even the risk that terrorist might use this time to improve their technical skills or other abilities (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 63).

Surveillance

Often attack planners conduct detailed surveillance of potential targets to determine what security measures are in place around the target and to assess whether they have the ability to get past them. They can go from pre-operation surveillance, before the operation is fully planned, to “dry runs” (e.g., O’Brien 2008; Stratfor 2016). Movement restrictions could affect in-person hostile ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) activities. Surveillance is key to counterterrorism, too, because it offers a fundamental opportunity to foil the attack by noting planner(s)’ actions (Stratfor 2016, pp. 2–4). Nevertheless, small-scale indiscriminate attacks by lone actors may require very little or no ISR. In general, in the short time, lockdown measures within countries and the closure of borders between countries should strengthen state control and monitoring capabilities.

Weapons acquisition

The weapons terrorist perpetrators use are generally crucial in defining the scale and scope of their operations (Jackson and Frelinger 2008, p. 583; see also Tishler 2018; Koehler-Derrick and Milton 2019). In the short term, the COVID-19 pandemic could offer new means for violence. Terrorists may try to use this virus as a weapon. This opportunity was soon imagined and recommended by violent extremists. For example, in May 2020, the sixth edition of Voice of Hind, a pro-Islamic State propaganda magazine, encouraged Muslims to become infected with the virus in order to spread it to security forces and disbelievers (Daymon and Criezis 2020, p. 31). For their part, on social networks, right-wing extremist groups in the United States have encouraged those of their followers who contracted COVID-19 to spread the disease to law enforcement, non-Whites, and Jews, for example, by spreading saliva on door handles at FBI offices or synagogues (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 65).

According to available information, these scenarios are not just a propaganda expedient. For example, on April 16, 2020, the Interior Ministry of Tunisia stated that an alleged member of a jihadist network and another man had been arrested in the southern part of the country as part of an investigation into a “terrorist plot” aimed at spreading the virus among security forces (Marone 2020). In addition to selective attacks, malicious actors could also intentionally spread SARS-CoV-2 in an indiscriminate manner, in order to prolong or reignite the pandemic on a large scale. At the time of writing, with the virus established in almost every country worldwide, such threats are unlikely to make an overwhelming difference on the ground. However, there could be a rhetorical benefit (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 65). In any case, the development of an effective and safe vaccine against the coronavirus and its administration to the population should close this window of opportunity.

In the medium to long term, the pandemic could also offer new ideas for reflection, with potentially more severe consequences. In fact, terrorists could draw inspiration from the COVID-19 pandemic and the disastrous effects it is creating to build biological weapons (Blum and Neumann 2020), despite all the technical and organizational difficulties associated with this ambition, at least in the absence of support from a state. Actually, highly pathogenic agents are hard to find, isolate, and spread (Blum and Neumann 2020). Thus, it is not surprising that only a relatively small portion of terrorists has been willing and able to engage in bioterrorism. Furthermore, most past cases have involved non-contagious agents such as Bacillus anthracis (the bacterium responsible for anthrax) and various biological toxins (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 64; see Binder and Ackerman 2019). Nevertheless, the inability of even highly developed countries, such as the United States, to effectively stop the spread of the virus have hardly gone unnoticed. Based on these experiences, particularly vicious terrorist groups might attempt to build new biological weapons to achieve their extremist goals (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 64).

In general, terrorists, that are accustomed to clandestinely struggle against a more powerful enemy in an asymmetric conflict, tend to be adaptive actors. Nevertheless, tactical innovations from scratch are not frequent in this field. As Silke and Filippidou (2020, p. 211) effectively noted, “[t]errorist groups demonstrate an apparent ability to develop and employ novel methods of attack. However, often these innovations do not always, or even usually, involve the introduction of new technologies or means, but can rather signify a different and original utilisation of existing means.”

Deployment

Once planning, training and weapons acquisition are complete, the attack team (or the perpetrator) can be deployed (e.g., Stratfor 2016). In the short term, the movement of perpetrators for the execution of attacks might be hampered, especially at the international level. For this reason, terrorists might decide to suspend their operations or at least to focus on close and known targets. These potential limitations might also indirectly influence the process of target selection. In fact, available empirical analyses on the distance traveled to commit terrorist attacks have shown that there is a trade-off between travel distance and the representative value of the target (Marchment and Gill 2020, p. 2): therefore, in countries with movement restrictions, terrorist might prefer low-value targets. This would be even more salient for lone actor terrorists who lack the resources and support of a group.

Moreover, COVID-19 might have an adverse effect on the security of a number of facilities in the West. While, in all likelihood, those guarding high-value targets (such as government buildings or diplomatic missions) remain on post during the pandemic, in other cases facilities might be left less secure than during normal undertakings because of operational or other limits (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 66).

Escape

Usually the execution of an act of terrorism is not over once the weapon is used for the attack. In fact, if perpetrators intend to stay at large, they have to find a way to exit the scene of the attack. For example, they will have to avoid security cameras, plan escape routes, or, for example, arrange getaway cars. Furthermore, they have to do so most likely under pressure, while running the risk of getting caught by the police, alerted after the attack. Clearly, this risk is higher when the terrorist operation requires that the perpetrators are physically present at the crime scene until the actual execution of the attack, as it happens when they make use of firearms or bladed weapons, as opposed to explosive devices with a timer or a remote detonator (van Dongen 2014, pp. 65–66). On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that in recent years several jihadist perpetrators (van Dongen 2017) engaged in genuine suicide missions (in which they sought death) or, more frequently, in “high-risk missions” (in which they did not plan to escape after the attack) (Gambetta 2005). Clearly, on such occasions, an exit plan is not required.

The COVID-19 pandemic could affect this phase in different ways. In countries under lockdown, it might be more difficult for perpetrators to blend into the population, since most ordinary citizens are required to stay home, while the presence of law enforcement in the streets may be massive. On the other hand, in countries where people can move without severe restrictions but are required or strongly advised to wear face masks, terrorists could take advantage of this unintentional opportunity to hide their identity. For example, it is interesting to recall that, before his arrest in Spain in April 2020, Abdel-Majed Abdel Bary, a high-level IS foreign fighter from Britain, was able to take advantage of the pandemic to remain in hiding in Andalusia: on the very rare occasions he left his house, the man always wore a face mask precisely “to avoid detection” (Spanish Ministry of the Interior 2020). Furthermore, at this stage, facial recognition systems have difficulties in identifying mask-wearing people (see McGee 2020).

Exploitation

For most terrorist groups, violence is not an end in itself but a means to reach their political ends. In the short term, the most obvious ends of violence deal with publicity. At least in the short term, the coronavirus crisis could affect the phase of exploitation as far as it could reduce the visibility of terrorist violence: in fact, in the ongoing situation the attention of the public in the world tends to be focused on the disease (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 65). Furthermore, the actual destructive capacity of terrorism, associated with any ideological orientation, pales in comparison to the impact of the pandemic in terms of victims and damages in the West and beyond. In this context, some terrorist groups might wait to take action until the threat posed by the pandemic appears to have shrunk (Silke 2020, p. 6). This in turn could temporarily reduce the risk of “copycat” effects, whereby some individuals are drawn to violent extremism and terrorism by the “noise around attacks” (Pantucci 2020, p. 2).

Counterterrorism (CT)

Violent extremists and terrorists could also benefit from the constraints and limitations that counterterrorism activities (among others, Crelinsten 2009) might suffer in this phase. In the short time, the COVID-19 pandemic could alter the traditional “cycle of intelligence” (e.g., Omand 2014) in intelligence services and law enforcement agencies. Collection might be undermined, especially when it comes to its classical HUMINT (human intelligence) component, based on the use of human sources (see Finley et al. 2020). Processing and analysis could also be affected; the emergency condition might reduce CT capabilities, for example with analysts teleworking or suffering personal stresses (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 66). Furthermore, the attention and energies of law enforcement agencies—and, at least in some Western countries, of a part of the military, too—might be partly diverted to new responsibilities and tasks related to the coronavirus crisis (Marone 2020). This potential vulnerability has been explicitly underlined by violent extremists in their propaganda; for example, in the editorial of Issue 226 of al-Naba’, published on March 19, 2020, IS emphasized that Western armies and security forces were “stretched to the maximum” in their support of government efforts to curb the spread of the virus (al-Lami 2020). Finally, in the medium to long term, the health crisis and the far-reaching consequences it is causing could even push governments to change their national security priorities, including in terms of fund allocation, potentially even to the detriment of the struggle against violent extremism (e.g., Pantucci 2020).

Conclusions

It is clear that the COVID-19 pandemic has established itself as a phenomenon of the greatest importance and could have huge implications and effects in the medium and long term, too. This unexpected macro-level phenomenon can represent a sort of global natural experiment in several fields. The article has explored its mixed impact on violent extremism and terrorism in the West.

The pandemic has had significant effects on all three levels of analysis (macro, meso, micro). In fact, it has already caused huge macro-level consequences, such as a severe global economic crisis, that in turn could potentially affect some radicalization pathways in the West (for example, job losses or other negative consequences of the economic crisis that could lead some individuals to accept extremist beliefs and even to participate in acts of violence). The pandemic can also influence the activities of extremist organizations and groups (for example, by leading them to adjust their propaganda or change their terrorist plans), at the meso level. And, finally, the pandemic can fuel individual attitudes and states of mind that tend to underlie various forms of violent extremism (for example, feelings of fear, uncertainty, and frustration) at the micro level.

Drawing on the existing literature, and without claiming to be exhaustive, our discussion can also suggest preliminary hypotheses that future empirical research based on available data will be able to robustly test (Ackerman and Peterson 2020, p. 60). As regard group pull factors, it will be interesting to analyze the evolution of extremist propaganda over time. In general, propaganda is a crucial aspect in violent extremism and terrorism and, unlike many other activities of these mainly clandestine phenomena, it is by definition clearly visible; thus, it is not surprising that it has attracted the attention of several scholars and experts, who have adopted different perspectives and methods in their works (e.g., Baele et al. 2019; Conway et al. 2019; Loadenthal 2017). Quantitative content analysis could verify a potential increase in the number of references to specific themes (such as divine punishment, in jihadist propaganda) and enemies (such as China and the Chinese people) related to COVID-19 that were arguably not central in the past. Content analysis could also take into consideration the use of rhetorical strategies such as conspiracy theories connected with the infectious disease.

Moreover, future research could investigate the actual influence of online radicalization after the coronavirus outbreak. First of all, as previously mentioned, at least in the short term, extremist search traffic could increase. Moreover, extremist online interactions could become even more relevant, at the expense of offline contacts. In general, as scholar and experts have noted, “evidence suggests that the digital sphere does not replace the real world in most instances” of radicalization into violent extremism; rather, “online and offline dynamics complement one another” (Meleagrou-Hitchens et al. 2017, p. 1248). However, at least during the most acute phases of the pandemic, online radicalization pathways could prevail.

Future scholarship could also verify the impact of the pandemic on extremist attitudes and beliefs in radicalization in the West. In general, this area of study can be complex and challenging; in particular, as a recent literature review on risk factors confirmed, “the preponderance of the scientific literature on terrorism is largely conceptual in nature, with a relatively limited number of empirical investigations” (Desmarais 2017, p. 195; see also Victoroff 2005). However, future analyses could focus on the relevance of individual pre-ideological negative states of mind due to the coronavirus crisis, such as feelings of frustration (see Hogg and Blaylock 2012, chapter 9; Jasko et al. 2017) and anger (see Horgan 2008, 84 ff.; Van Stekelenburg 2017), and, in particular, the influence of trigger events in personal life (for example, a trauma, a job loss, financial issues) (see also Kruglanki and Fishman 2009). Cases such as Corey H.’s incident, in which strictly personal states of mind and grievances are projected onto ideological motivations, could become even more frequent. Moreover, further empirical research on the effects of uncertainty (Hogg and Blaylock 2012) would be particularly welcome.

Finally, the pandemic and its direct consequences could have an impact on the characteristics of terrorist violence in the West (cf. Vidino et al. 2017; Nesser 2019; Ravndal et al. 2020; Marone 2015). In particular, future research could verify changes in target selection after the coronavirus outbreak. For example, on the one hand, in countries under a national lockdown or with serious restrictions, there might be a decrease in the number of indiscriminate attack plots on easy targets, particularly in closed public places or on public transport. On the other hand, hospitals and medical personnel might become targets of violence; especially in countries or areas with severe restrictions on the movement of ordinary citizens, there might be an increased focus on members of law enforcement; finally, political leaders who are responsible for the imposition of restrictive measures could attract the attention of ill-intentioned actors. When it comes to planning,4 it would be useful to test the hypothesis of a decrease in the number of conventional terrorist plots and attacks that require complex plans, face-to-face contacts among several operatives, and international trips, in countries or areas with severe restrictions. In addition, aspiring terrorists might attempt to use this virus as a weapon during the pandemic and, in the middle to long term, they could pay more attention and devote more energy to plans to build biological weapons, despite all the technical and organizational difficulties associated with this ambition.

At this stage, it can be argued that the ongoing crisis offers both constraints and opportunities for violent extremism and terrorism. For example, in the short time, lockdown measures can inhibit complex terrorist attacks, but at the same time they can amplify the influence of extremist propaganda, especially on the Web (Silke 2020). In general, since terrorists tend to be adaptive actors, it is necessary to maintain a strong focus on this threat. In conclusion, the direct impact of the pandemic on violent extremism and terrorism in the West certainly deserves attention; nevertheless, it should essentially come to an end with the administration of an effective and safe vaccine to the population. On the other hand, indirectly, the impact of its economic, social, political, and cultural consequences might be even more profound and lasting.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The in-group / out-group dichotomy was made popular by social psychologists Henri Tajfel and John C. Turner, pioneers of social identity theory, an influential approach in the study of intergroup dynamics (see, in particular, Tajfel and Turner 1979). In brief, an in-group is a social category or group with which an individual psychologically identifies strongly, while an out-group, conversely, is a social category or group with which an individual does not identify and which is excluded from the in-group. The dichotomy has been often used to study violent extremism. For example, according to Berger (2018, p. 46), “[v]iolent extremism is the belief that an in-group’s success or survival can never be separated from the need for violent action against an outgroup.”

The analysis of state terrorism or “state terror,” however relevant, is beyond the scope of this article. Cf. Stohl (2006).

The concept of cyberterrorism is elusive and problematic. In particular, among researchers “opinion [is] split as to whether an act must result in physical harm to people or property in order to qualify as an instance of cyberterrorism” (Macdonald et al. 2019, p. 9). In this article, in line with our definition of terrorism, the concept is associated with computer-based attacks that result in physical violence against people.

In general, it is worth mentioning that, while the study of terrorist plots is valuable (see Nesser 2019), unfortunately, empirical analysis on terrorist plans and decisions (e.g., Torres Soriano 2019) can be challenging, because of their clandestine nature.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ackerman, G., and H. Peterson. 2020. Terrorism and COVID-19: Actual and potential impacts. Perspectives on Terrorism 14 (3): 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, A., and B. Clifford. 2019. Doxing and defacements: Examining the Islamic state’s hacking capabilities. CTC Sentinel 12 (4): 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Lami, M. 2020. Jihadists see COVID-19 as an opportunity. The Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET). 1st June. https://gnet-research.org/2020/06/01/jihadists-see-covid-19-as-an-opportunity/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Al-Tamimi, A.J. 2020. Coronavirus and official Islamic state output: An analysis. The Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET). 15 April. https://gnet-research.org/2020/04/15/coronavirus-and-official-islamic-state-output-an-analysis/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Amarasingam, A., and M.-A. Argentino. 2020. The QAnon conspiracy theory: A security threat in the making? CTC Sentinel 13 (7): 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Asal, V.H., R.K. Rethemeyer, I. Anderson, A. Stein, J. Rizzo, and M. Rozea. 2009. The softest of targets: A study on terrorist target selection. Journal of Applied Security Research 4 (3): 258–278. [Google Scholar]

- Baele, S.J., K.A. Boyd, and T.G. Coan, eds. 2019. ISIS propaganda: A full-spectrum extremist message. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2020. Coronavirus: Man planning to bomb Missouri hospital killed, FBI says. BBC News, 26 March. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52045958. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Benford, R.D., and D.A. Snow. 2000. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–639. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J.M. 2018. Extremism. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R. 2017. These are not the terrorist groups you’re looking for: An assessment of the cyber capabilities of Islamic State. Journal of Cyber Policy 2 (2): 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Berntzen, L.E., and S. Sandberg. 2014. The collective nature of lone wolf terrorism: Anders Behring Breivik and the anti-Islamic social movement. Terrorism and Political Violence 26 (5): 759–779. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, M.K., and G.A. Ackerman. 2019. Pick your POICN: Introducing the profiles of incidents involving CBRN and non-state actors (POICN) database. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 10.1080/1057610X.2019.1577541. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørgo, T., and J.A. Ravndal. 2019. Extreme-right violence and terrorism: Concepts, patterns, and responses. ICCT Policy Brief. 23 September. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). https://icct.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Extreme-Right-Violence-and-Terrorism-Concepts-Patterns-and-Responses-4.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Blum, M.-M., and P.R. Neumann. 2020. Corona and bioterrorism: How serious is the threat? Commentary. War on the Rocks. 22 June, https://warontherocks.com/2020/06/corona-and-bioterrorism-how-serious-is-the-threat/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Borghard, D.E., and S.W. Lonergan. 2019. Cyber operations as imperfect tools of escalation. Strategic Studies Quarterly 13 (3): 122–145. [Google Scholar]

- Buil-Gil, D., F. Miró-Llinares, A. Moneva, S. Kemp, and N. Díaz-Castaño. 2020. Cybercrime and shifts in opportunities during COVID-19: A preliminary analysis in the UK. European Societies. 10.1080/14616696.2020.1804973. [Google Scholar]

- Comerford. M., and J. Davey. 2020. Comparing Jihadist and far-right extremist narratives on COVID-19. Global Network on Extremism & Technology, 27 April. https://gnet-research.org/2020/04/27/comparing-jihadist-and-far-right-extremist-narratives-on-covid-19/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Conway, M., R. Scrivens, and L. McNair. 2019. Right-wing extremists’ persistent online presence: History and contemporary trends. ICCT Research Paper. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). https://icct.nl/publication/right-wing-extremists-persistent-online-presence-history-and-contemporary-trends/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Crelinsten, R. 2009. Counterterrorism. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daymon, C., and M. Criezis. 2020. Pandemic narratives: pro-Islamic state media and the coronavirus. CTC Sentinel 13 (6): 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden, L. 2020. Coronavirus: Terror threat to hospitals as extremists call for attacks during lockdown. The Independent, 21 April, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/coronavirus-lockdown-hospitals-nhs-terror-threat-5g-conspiracy-theory-a9476066.html. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- De la Calle, L., and I. Sánchez-Cuenca. 2006. The production of terrorist violence: Analyzing target selection within the IRA and ETA, Estudio/Working Paper 2006/230, Madrid, Instituto Juan March.

- Della Porta, D. 2013. Clandestine political violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais, S.L., J. Simons-Rudolph, C.S. Brugh, E. Schilling, and C. Hoggan. 2017. The state of scientific knowledge regarding factors associated with terrorism. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management 4 (4): 180–209. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, C.J.M. 1998. The role of ideology in terrorists’ target selection. Terrorism and Political Violence 10 (2): 53–85. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, A., J. Mendez, and D. Priess. 2020. How do you spy when the world is shut down? Lawfare. 20 March. https://www.lawfareblog.com/how-do-you-spy-when-world-shut-down. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Fischbacher-Smith, D., and M. Fischbacher-Smith. 2013. The vulnerability of public spaces: Challenges for UK hospitals under the ‘new’ terrorist threat. Public Management Review 15 (3): 330–343. [Google Scholar]

- Gambetta, D., ed. 2005. Making sense of suicide missions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gambetta, D., and S. Hertog. 2017. Engineers of Jihad: The curious connection between violent extremism and education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ganor, B., and M. Halperin Wernli. 2013. Terrorist attacks against hospitals: Case studies. Working Paper. International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). http://www.ict.org.il/Article/77/Terrorist-Attacks-against-Hospitals-Case-Studies. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Gill, P., Z. Marchment, E. Corner, and N. Bouhana. 2020. Terrorist decision making in the context of risk, attack planning, and attack commission. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 43 (2): 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, T.R. 1970. Why men rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, M.M. 2016. The ties that bind: How terrorists exploit family bonds. CTC Sentinel 9 (2): 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, M., and C. Mullins. 2015. The radicalization puzzle: A theoretical synthesis of empirical approaches to homegrown extremism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38 (11): 958–975. [Google Scholar]

- Halverson, J., S. Corman, and H.L. Goodall. 2011. Master narratives of Islamist extremism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A., and D.L. Blaylock, eds. 2012. Extremism and the psychology of uncertainty. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan, J. 2008. From profiles to pathways and roots to routes: Perspectives from psychology on radicalization into terrorism. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618: 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- ICG. 2020. Contending with ISIS in the time of coronavirus. Commentary. International Crisis Group. 31 March. https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/contending-isis-time-coronavirus. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Jackson, B.A., and D.R. Frelinger. 2008. Rifling through the terrorists’ arsenal: Exploring groups’ weapon choices and technology strategies. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 31 (7): 583–604. [Google Scholar]

- Jasko, K., G. LaFree, and A. Kruglanski. 2017. Quest for significance and violent extremism: The case of domestic radicalization. Political Psychology 38 (5): 815–831. [Google Scholar]

- Jolley, D., and J.L. Paterson. 2020. Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. British Journal of Social Psychology 59 (3): 628–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassimeris, G. 2011. Greece’s new generation of terrorists: The revolutionary struggle. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 34 (3): 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler-Derrick, G., and D.J. Milton. 2019. Choose your weapon: The impact of strategic considerations and resource constraints on terrorist group weapon selection. Terrorism and Political Violence 31 (5): 909–928. [Google Scholar]

- Koomen, W., and J. Van Der Pligt. 2015. The psychology of radicalization and terrorism. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski, A.W., and S. Fishman. 2009. Psychological factors in terrorism and counterterrorism: Individual, group, and organizational levels of analysis. Social Issues and Policy Review 3 (1): 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, J. 2020. QAnon’s madness is turning Canadians into potential assassins: The sprawling conspiracy theory has mutated across borders. Foreign Policy. 13 July. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/13/qanon-canada-trudeau-conspiracy-theory/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Loadenthal, M. 2017. The politics of attack: Communiqués and insurrectionary violence. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loadenthal, M. 2020. The 2020 Pandemic and its effect on anarchist activity. In Extremism and terrorism in a time of pandemic, ed. F. Marone. Dossier. ISPI – Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 15 May. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/2020-pandemic-and-its-effect-anarchist-activity-26157. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Macdonald, S., L. Jarvis, and S.M. Lavis. 2019. Cyberterrorism today? Findings from a follow-on survey of researchers. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 10.1080/1057610X.2019.1696444. [Google Scholar]

- Mahood, S., and H. Rane. 2017. Islamist narratives in ISIS recruitment propaganda. The Journal of International Communication 23 (1): 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, N. 2020. Self-isolation might stop coronavirus, but it will speed the spread of extremism. Foreign Policy. 26 March. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/26/self-isolation-might-stop-coronavirus-but-spread-extremism/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Marchment, Z., and P. Gill. 2020. Spatial decision making of terrorist target selection: Introducing the TRACK framework. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 10.1080/1057610X.2020.1711588. [Google Scholar]

- Marone, F. 2015. The rise of insurrectionary anarchist terrorism in Italy. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 8 (3): 194–214. [Google Scholar]

- Marone, F. 2017. Ties that bind: Dynamics of group radicalisation in Italy’s Jihadists headed for Syria and Iraq. The International Spectator 52 (3): 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Marone, F. 2019. Violent extremism and the internet. In Digital Jihad: Online communication and violent extremism, ed. F. Marone, 10–25. Milan: ISPI – Italian Institute for International Political Studies. https://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/ispi-digitaljihad_web.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Marone, F. 2020. Terrorism and counterterrorism in a time of pandemic. In Extremism and terrorism in a time of pandemic, ed. F. Marone. Dossier. ISPI – Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 15 May. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/terrorism-and-counterterrorism-time-pandemic-26165. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- McCauley, C., and S. Moskalenko. 2008. Mechanisms of political radicalization: Pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence 20 (3): 415–433. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, C., and S. Moskalenko. 2011. Friction: How radicalization happens to them and us. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, L. 2020. We’re headed for a faceless future as masks become the norm. That’s a big security concern, experts say. CNN. 10 May. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/10/world/face-masks-security-intl-gbr/index.html. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- McNeil-Willson, R. 2020. Framing in times of crisis: Responses to COVID-19 amongst Far Right movements and organisations, ICCT Research Paper. June. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). https://icct.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Framing-in-times-of-crisis-Responses-to-COVID-19-amongst-Far-Right-movements-and-organisations.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Meleagrou-Hitchens, A., and B. Crawford. 2020. 5G and the far right: How extremists capitalise on coronavirus conspiracies. Global Network on Extremism & Technology (GNET). 21 April. https://gnet-research.org/2020/04/21/5g-and-the-far-right-how-extremists-capitalise-on-coronavirus-conspiracies/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Meleagrou-Hitchens, A., A. Alexander, and N. Kaderbhai. 2017. The impact of digital communications technology on radicalization and recruitment. International Affairs 93 (5): 1233–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Merari, A. 1993. Terrorism as a strategy of insurgency. Terrorism and Political Violence 5 (4): 213–251. [Google Scholar]

- Moonshot. 2020a. COVID-19: Searches for white supremacist content are increasing. Moonshot CVE. 14 April. http://moonshotcve.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Social-Distancing-and-White-Supremacist-Content_Moonshot.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Moonshot. 2020b. Covid-19: Increase in far-right searches in Canada. Moonshot CVE. 8 June. http://moonshotcve.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Canadian-Search-Traffic_Moonshot-CVE.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Nesser, P. 2019. Military interventions, Jihadi networks, and terrorist entrepreneurs: How the Islamic state terror wave rose so high in Europe. CTC Sentinel 12 (3): 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, K.A. 2008. Assessing hostile reconnaissance and terrorist intelligence activities: The case for a counter strategy. The RUSI Journal 153 (5): 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Omand, D. 2014. The cycle of intelligence. In Routledge companion to intelligence studies, ed. R. Dover, M.S. Goodman, and C. Hillebrand, 59–70. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pantucci, R. 2020. Key questions for counter-terrorism post-COVID-19. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 12 (3): 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski, T., A. Abdollahi, S. Solomon, J. Greenberg, F. Cohen, and D. Weise. 2006. Mortality salience, martyrdom, and military might: The great Satan versus the axis of evil. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 32 (4): 525–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal, A.S., S. Lygren, A.R. Jupskås, and T. Bjørgo. 2020. RTV trend Report 2020: Right-wing terrorism and violence in Western Europe, 1990 - 2019. C-REX Research Report. Center for Research on Extremism (C-REX). https://www.sv.uio.no/c-rex/english/topics/online-resources/rtv-dataset/index.html. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Rising, D. 2020. EU official warns of extremists exploiting virus outbreak. AP News, 13 May. https://apnews.com/b7775b649b945bb548f097d65cd3d2d6. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Sageman, M. 2004. Understanding terror networks. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, A.P., ed. 2011. The Routledge handbook of terrorism research. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, A.P. 2013. Radicalisation, de-radicalisation, counter-radicalisation: A conceptual discussion and literature review. ICCT Research Paper. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). https://icct.nl/publication/radicalisation-de-radicalisation-counter-radicalisation-a-conceptual-discussion-and-literature-review/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Schmid, A.P. 2015. Challenging the Narrative of the ‘Islamic State’. ICCT Research Paper. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). http://icct.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ICCT-Schmid-Challenging-the-Narrative-of-the-Islamic-State-June2015.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Serafini, G., B. Parmigiani, A. Amerio, A. Aguglia, L. Sher, and M. Amore. 2020. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2: 89. 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silke, A. 2020. COVID-19 and terrorism: Assessing the short-and long-term impacts. Commentary. Pool Re and Cranfield University. 7 May. https://www.cranfield.ac.uk/press/news-2020/covid19-and-terrorism-assessing-the-short-and-longterm-impacts. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Silke, A., ed. 2014. Prisons, terrorism and extremism: Critical issues in management, radicalisation and reform. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silke, A., and A. Filippidou. 2020. What drives terrorist innovation? Lessons from Black September and Munich 1972. Security Journal 33 (2): 210–227. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, D.A., and S. Byrd. 2007. Ideology, framing processes, and Islamic terrorist movements. Mobilization: An International Quarterly Review 12 (1): 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Ministry of the Interior. 2020. La Policía Nacional detiene en Almería a uno de los Foreign Terrorist Fighters de DAESH más buscados de Europa [The National Police detain one of the most wanted DAESH Foreign Terrorist Fighters in Europe in Almería]. Ministerio del Interior, Policía Nacional, 21 April. http://www.interior.gob.es/web/interior/noticias/detalle/-/journal_content/56_INSTANCE_1YSSI3xiWuPH/10180/11777022. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Stephenson, M., and A. Connolly. 2020. Alleged Rideau Hall intruder cited need for wake-up call in letter: sources. Global News. 7 July. https://globalnews.ca/news/7149667/corey-hurren-rideau-hall-incident-letter/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Stern, S., J. Ware, and N. Harrington. 2020. Terrorist targeting in the age of coronavirus. International Counter-Terrorism Review 1: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stohl, M. 2006. The state as terrorist: Insights and implications. Democracy and Security 2 (1): 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Stratfor. 2016. Understanding the terrorist attack cycle and its vulnerabilities. Report. Stratfor. https://lp.stratfor.com/terrorist-attack-cycle-threat-lens-report. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Tajfel, H., and J.C. Turner. 1979. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The social psychology of intergroup relations, ed. W.G. Austin and S. Worchel, 33–47. Monterey: Brooks-Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E., and M. Brewster. 2020. Rangers group facing probe over reservist's far-right ties touted role in watching for 'illegal immigrants'. CBC News, 9 September. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/rangers-army-immigration-militias-1.5715795. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

- Tishler, N.A. 2018. Trends in terrorists’ weapons adoption and the study thereof. International Studies Review 20 (3): 368–394. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Soriano, M.R. 2019. How do terrorists choose their targets for an attack? The view from inside an independent cell. Terrorism and Political Violence. 10.1080/09546553.2019.1613983. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Justice. 2020a. Pakistani doctor charged with attempting to provide material support to ISIS. The United States Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 19 March. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/pakistani-doctor-charged-attempting-provide-material-support-isis. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- US Department of Justice. 2020b. Train operator at port of Los Angeles charged with derailing locomotive near U.S. Navy’s hospital ship mercy. The United States Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 1 April. https://www.justice.gov/usao-cdca/pr/train-operator-port-los-angeles-charged-derailing-locomotive-near-us-navy-s-hospital. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Van den Bos, K. 2020. Unfairness and radicalization. Annual Review of Psychology 71: 563–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen, T. 2014. The lengths terrorists go to: Perpetrator characteristics and the complexity of Jihadist terrorist attacks in Europe, 2004–2011. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 6 (1): 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen, T. 2017. The fate of the perpetrator in the Jihadist modus operandi: Suicide attacks and non-suicide attacks in the West, 2004–2017. ICCT Research Paper. December. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). https://icct.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/VanDongen-The-Fate-of-the-Perpetrator-December2017.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Van Prooijen, J.W., A.P. Krouwel, and T.V. Pollet. 2015. Political extremism predicts belief in conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science 6 (5): 570–578. [Google Scholar]

- Van Stekelenburg, J. 2017. Radicalization and violent emotions. PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (4): 936–939. [Google Scholar]

- Victoroff, J. 2005. The mind of the terrorist: A review and critique of psychological approaches. Journal of Conflict Resolution 49 (1): 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vidino, L., F. Marone, and E. Entenmann. 2017. Fear thy neighbor: Radicalization and jihadist attacks in the West. Milan: ISPI – Program on Extremism at George Washington University – ICCT-The Hague.

- VSSE. 2020. The hidden danger behind COVID-19. Document in English. Veiligheid van de Staat - Sûreté de l’État (VSSE). 21 April. https://vsse.be/fr/le-danger-cache-derriere-le-covid-19. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Wither, J.K. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A preliminary assessment of the impact on terrorism in Western States. Occasional Paper. April 2020. George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/occasional-papers/covid-19-pandemic-preliminary-assessment-impact-terrorism-western-states. Accessed 14 July 2020.