Abstract

Purpose

Galactokinase (GALK1) deficiency is a rare hereditary galactose metabolism disorder. Beyond cataract, the phenotypic spectrum is questionable. Data from affected patients included in the Galactosemias Network registry were collected to better characterize the phenotype.

Methods

Observational study collecting medical data of 53 not previously reported GALK1 deficient patients from 17 centers in 11 countries from December 2014 to April 2020.

Results

Neonatal or childhood cataract was reported in 15 and 4 patients respectively. The occurrence of neonatal hypoglycemia and infection were comparable with the general population, whereas bleeding diathesis (8.1% versus 2.17–5.9%) and encephalopathy (3.9% versus 0.3%) were reported more often. Elevated transaminases were seen in 25.5%. Cognitive delay was reported in 5 patients. Urinary galactitol was elevated in all patients at diagnosis; five showed unexpected Gal-1-P increase. Most patients showed enzyme activities ≤1%. Eleven different genotypes were described, including six unpublished variants. The majority was homozygous for NM_000154.1:c.82C>A (p.Pro28Thr). Thirty-five patients were diagnosed following newborn screening, which was clearly beneficial.

Conclusion

The phenotype of GALK1 deficiency may include neonatal elevation of transaminases, bleeding diathesis, and encephalopathy in addition to cataract. Potential complications beyond the neonatal period are not systematically surveyed and a better delineation is needed.

Keywords: galactokinase 1 deficiency, cataract; galactosemias registry, GALK1 gene variants; neonatal complications

INTRODUCTION

Hereditary galactosemias are a group of disorders caused by genetic defects in galactose metabolism. Galactosemia type II (OMIM 230200), also known as galactokinase (GALK1; EC 2.7.1.6) deficiency, has a worldwide incidence of 1:1,000,000,1 although it can be higher in regions with a founder effect. However, since many newborn screening (NBS) programs do not detect GALK1 deficiency, this incidence is probably an underestimation. The first description dates back to 1933 when Fanconi2 described a patient with cataract associated with milk ingestion, a condition he termed galactose diabetes. It was in 1965 that Gitzelmann3 discovered that this patient suffered from GALK1 deficiency.8

Two galactokinase-like genes can be distinguished. GALK1 (OMIM *604313), located on chromosome 17q24, encodes galactokinase and is involved in galactose metabolism. GALK2 (OMIM *137028), located on chromosome 15q21.1-q21.2, encodes N-acetylgalactosamine kinase (EC 2.7.1.157) and is not primarily involved in galactose metabolism.4 Galactokinase is part of the GHMP superfamily of structurally similar proteins, which comprises mostly small molecule kinase enzymes. The abbreviation GHMP refers to the involved kinases: galactokinase, homoserine kinase, mevalonate kinase, and phosphomevalonate kinase.5 Kinetically, human galactokinase follows an ordered ternary complex mechanism, with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding first. The human enzyme is intolerant to many single amino acid substitutions. This is important in the molecular pathology of GALK1 deficiency.6,7 Variants in the GALK1 gene are associated with GALK1 deficiency and, at present, the mutational spectrum comprises more than 30 variants. The most frequent disease-causing variants are the founder variant NM_000154.1:c.82C>A (p.Pro28Thr), common in the Roma population, and the Osaka variant NM_000154.1:c.593C>T (p.Ala198Val), common in the Japanese and Korean populations.6

In human metabolism, galactose is essential for the galactosylation of complex molecules. In addition to the dietary source, there is endogenous production that mainly occurs from the turnover of glycoconjugates.8 Galactose is mainly processed through the Leloir pathway, in which the first enzyme GALK1 catalyzes the conversion of α-d-galactose to α-d-galactose-1-phosphate (Gal-1-P) at the expense of ATP. In erythrocytes of healthy controls the range of the GALK1 activity measured by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS assays) is 1.0–2.7 μmol·(g Hgb)−1·hr−1, with a mean GALK1 activity of 1.8 ± 0.43 μmol·(g Hgb)−1·hr−1.9

GALK1 deficient patients are biochemically characterized by hypergalactosemia and elevated values of galactitol and galactonic acid resulting from the activation of the reductive and oxidative pathways of galactose disposal. In GALK1 deficient patients these galactitol levels can rise to 2500 mmol/mol creatinine prior to diet therapy. After introduction of the diet, the urinary galactitol values significantly decrease.10,11

Bilateral cataract, characterized by central lens opacities with the appearance of an oil droplet, seems to be the only consistent manifestation in patients with GALK1 deficiency. Accumulation of galactitol, due to the conversion of excess galactose by aldose reductase, is responsible for the development of cataracts.12 In the presence of hypergalactosemia, high amounts of galactose are transported to the lens cells. Aldose reductase is abundantly present in the epithelial cells, located at the anterior side of the lens.13 Subsequently, high levels of galactose are reduced to galactitol, creating an osmotic phenomenon with lens swelling, lysis, and sugar cataracts as the result.14 Using their mouse model, Ai et al.12 showed the link between the development of cataract and the level of aldose reductase in lens cells. GALK1 knockout mice did not develop cataract when fed a galactose diet due to absent expression of aldose reductase in the lens cells. However, after introduction of the human aldose reductase transgene, these knockout mice developed cataract within the first day of life.12 In humans, cataracts can be resolved by dietary restriction of galactose if the diet is initiated before the second month of life. If the diet is not timely instituted and vision impairment has already occurred, surgical intervention is needed.15

In addition to cataracts, neonatal complications such as hepatosplenomegaly, hypoglycemia, and failure to thrive have been reported. Pseudotumor cerebri has also been described and its development is related to the accumulation of galactitol in the brain cells with subsequent cerebral edema as result.16 Other manifestations, such as intellectual disability and developmental delay, have been reported.10,17 It is arguable whether other manifestations are the result of GALK1 deficiency or related to other genetic, epigenetic, or environmental factors. However, these findings have raised questions about the true phenotypic spectrum of this entity. In an effort to gather more data internationally and survey the occurrence of other symptoms in addition to cataract, the GalNet registry data were used. This registry was created in 2014 by the members of the Galactosemia Network (GalNet, www.galactosemianetwork.org).18 In this study, we present the data of 53 previously unpublished patients from different countries, aiming to characterize the phenotypic spectrum and the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of this entity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

The international network for the galactosemias (GalNet), established in 2012, has developed an online registry (https://ecrf.ctcm.nl/macro/) that includes patients with the different galactosemias from several countries as described in Rubio-Gozalbo et al.19 It was established in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and following General Data Protection Regulation. The local ethics committee of the coordinating center (Maastricht University Medical Center) approved the study (application number METC 13–4–121.6/ab), which was subsequently approved by participating partners. All patients or their authorized representatives gave written consent.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Between December 2014 and April 2020, data of patients with established GALK1 deficiency were collected. In total, 53 patients were included. GALK1 deficiency was defined as GALK1 enzyme activity below 20% of reference value and/or GALK1 disease-causing variants.

Predicted structural effects on GALK1 enzyme

Changes in protein stability of unpublished variants were estimated in silico using PredictSNP.20

Statistical analysis

Data for analysis were exported from the original database in MACRO to SPSS. Medians and ranges for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables were calculated with descriptive analyses. All clinical outcomes were classified as absent or present to calculate the associations between clinical outcomes and variables using Fisher’s exact test; p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For some variables, p values with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are described. Because of the high amount of missing data, the valid number, defined as the number of available data per variable, was used for expressing the statistical findings in percentages. These missing data were a consequence of the retrospective nature of data collection or due to the young age of patients, which hampered evaluation of long-term follow-up. The results of the statistical analyses may be biased, when >10% of the data were missing.21

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

A total of 53 patients, not previously reported in the literature, and originating from 11 countries and 17 different centers, were included in this study (Table 1). The gender was not equally distributed (64.2% male and 35.8% female), with a median age of 10.4 years (range: 1–35). Most patients were Caucasian. In total, 35 patients were diagnosed following NBS (Table S1). Although more patients with GALK1 deficiency are known at several centers, they could not be included due to loss of follow-up (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participating countries and centers.

| Country | Center | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Countries and centers with number of included GALK1 deficient patients | ||

| Austria | Medizinische Universität Wien, Vienna | 6 |

| Universitätsklink für Pädiatrie, Tirol Kliniken GmbH, Innsbruck | 3 | |

| University Children’s Hospital, Parcelsus Medical University, Salzburg | 1 | |

| Belgium | University Hospital Ghent | 1 |

| University Hospital Leuven | 2 | |

| Queen Fabiola Children’s University Hospital | 2 | |

| France | Hôpital Antoine Béclère, Clamart | 1 |

| Germany | Clinic for Pediatric Kidney, Liver and Metabolic Diseasesa | 15 |

| Greece | Agia Sofia Children’s Hospitala | 1 |

| Ireland | National Centre for Inherited Metabolic Disorders | 1 |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam Medical Center | 2 |

| Portugal | Hospital Santa Maria Lisboa | 3 |

| Spain | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago | 5 |

| Hospital Sant Joan de Déu | 5 | |

| Switzerland | Inselspital, University Hospital, Bern | 1 |

| USA | Boston Children’s Hospital | 1 |

| Children’s Hospital of Philadelphiaa | 3 | |

| Total | 53 | |

| Country and center(s) with GALK1 deficient patients not included in article | ||

| Croatia | Klinički bolnički centar Zagreb | 2 |

| Ireland | Temple Street Children’s University Hospital | 1 |

| Netherlands | Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam | 1 |

| Maastricht University Medical Center | 1 | |

| University Medical Center Groningen | 1 | |

| Spain | Hospital Clinic de Barcelona | 1 |

| Total | 7 | |

aCenter to be included in GalNet Registry.

Phenotypic spectrum

Cataract

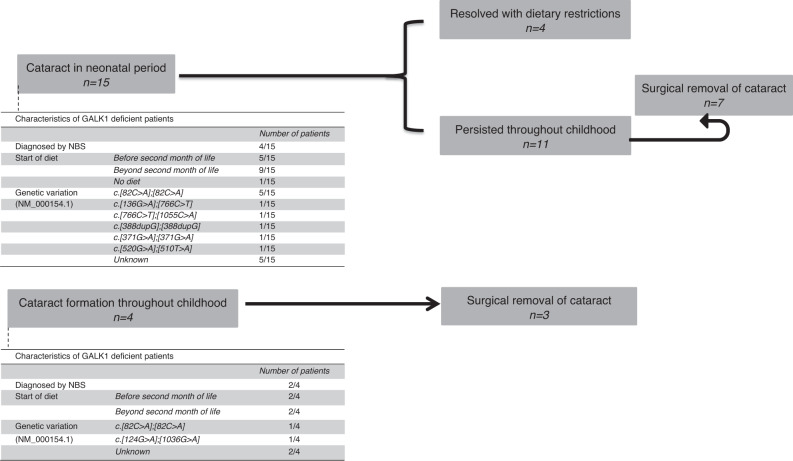

Fifteen of the reported 53 patients (28.3%) showed cataract in the neonatal period; in 1 patient it was not clear whether the cataract was present neonatally. Neonatal cataract that persisted throughout childhood was reported in 11 of these 15 patients and in 7 of them surgical removal was performed. In the other patients, neonatal cataract resolved with dietary restrictions. The occurrence of neonatal cataract was significantly lower in patients with initiation of diet within the first two months of life (p < 0.001) and was less frequently reported in patients diagnosed by NBS (p < 0.001). New lenticular changes in childhood were reported in 4 patients and in 3 of them surgical removal of the cataract was performed because of impaired vision (Table S1, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Cataract formation in study population.

A total of 15 patients were reported with cataract in the neonatal period. Characteristics of the patients with neonatal cataract are shown in the figure above. In 4 patients, cataract resolved after initiation of dietary restrictions. In the other 11 patients, the cataract persisted through childhood and in 7 patients surgical removal was performed. Cataract formation throughout childhood was reported in 4 patients; surgical removal was performed in 3. NBS newborn screening.

Neonatal illness

In the registry, acute neonatal illness was defined as having one of the following symptoms or findings: elevated transaminases (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] or aspartate aminotransferase [AST] > 30 U/L), bleeding diathesis (abnormal prothrombin time [PT] and/or activated partial thromboplastin time [APTT]), encephalopathy (depressed consciousness with or without neurological signs), clinical signs of infection, and/or hypoglycemia (glucose < 2.6 mmol/L). The different parameters were not reported in all 53 patients. The given numbers refer to the patients in which the specific parameter was assessed. The most common sign in the neonatal period was the elevated transaminases in 12 of the 47 (25.5%) patients. In addition, 3 of the reported 37 (8.1%) showed bleeding diathesis, 2 of the reported 51 (3.9%) patients showed encephalopathy, 1 of the reported 50 (2.0%) patients showed signs of infection, and 2 of the reported 47 (4.3%) showed hypoglycemia (Table S1).

Neurological and cognitive complications

Developmental delay was assessed in 47 patients, of whom 3 suffered from cognitive developmental delay, 2 suffered from motor developmental delay, and 2 from developmental delay on both domains. Of these 7 patients in whom developmental delay was reported, three suffered from acute neonatal illness. In 4 patients with developmental delay, cataract was reported. Three of the 4 patients with cataract developed the cataract in the neonatal period; the other was reported with lenticular changes during childhood (Table S1). No significant association was found between the occurrence of cataract and the presence of developmental delay. The occurrence of developmental delay was less frequently reported in patients diagnosed following NBS (p = 0.029, but not significant after Bonferroni).

Language delay was present in 3 of the 34 patients (8.8%) in whom language delay was assessed. Three of the reported 40 patients (7.5%) suffered from speech disorders. In addition, other symptoms such as movement disorders including tremor, dystonia, ataxia, and general motor abnormalities; microcephaly; and psychiatric disorders such as attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder and anxiety disorder were reported in some patients (Table S1).

Female gonads

In 8 of 19 female patients, gonadal follow-up was reported. One of them showed delayed puberty and 7 of the 8 patients had a spontaneous puberty. No primary ovarian insufficiency was reported (Table S1).

Bone health

Vitamin D levels, calcium intake, physical activity, and fractures were included in the electronic case report form (eCRF). In 13 patients the vitamin D levels were assessed. Vitamin D levels between 50 and 75 nmol/L were defined as insufficient and levels below 50 nmol/L were defined as deficient. Vitamin D deficiency was reported in 9 patients, vitamin D insufficiency in 2 patients, and normal vitamin D levels were seen in 2 patients. Among the 45 patients in whom the usage of supplements was reported, 1 patient only used calcium supplements, 15 patients only used vitamin D supplements, and 11 patients used both calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Recommended physical activity was defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) as 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity per day for children and 150 minutes per week for adults. The physical activity was assessed in 20 patients; it was sufficient in 14 and insufficient in 6. Bone fractures were not reported in any of the 23 patients.

Metabolites

Data on urinary galactitol concentrations were available in 18 patients, with the most recent galactitol values reported in 13 patients. Ten of these 13 patients showed elevated levels (Table S1). In 23 patients, information about total galactose in blood at diagnosis was available and showed an increased total galactose. Surprisingly, increased Gal-1-P values during the neonatal period were reported in 5 patients, returning to normal beyond the neonatal period. In patients 4, 18, and 41 the Gal-1-P values were 14.0, 13.8, and 24.2 mg/dL respectively (reference: <10.0 mg/dL) and in patients 14 and 15 they were 0.20 and 0.30 µmol/g Hb respectively (reference: <0.05 µmol/g Hb) (Table S1).

Enzymatic measurements and genotype

In 29 patients the GALK1 gene (NM_000154.1) variant was reported. The genotypic spectrum revealed that 17 of 26 patients were homozygous for the most common variant NM_000154.1:c.82C>A (p.Pro28Thr). In 44 patients the enzyme activity was described: <1% in 27 patients, between 1% and 5% in 14 patients, and >10% in 3 patients (11.6%, 16.1%, and 18.0%). No statistically significant associations were found with enzyme activities <1% or ≥1% and clinical outcomes neonatal cataract (p = 0.082; OR 0.176 [0.029–1.051]), any sign of acute neonatal illness (p = 0.480; OR 2.074 [0.463–9.291]) and motor or mental or both developmental delay (p = 0.668; OR 0.619 [0.108–3.539]).

The most common genotype NM_000154.1:c.[82C>A];[82C>A] was associated with an enzyme activity between 0% and 3%. The genetic variants NM_000154.1:c.[1144C>T];[1144C>T] and NM_000154.1:c.[149G>T];[149G>T] were reported with enzyme activities of 0% and between 0% and 0.4%, respectively (Table S1).

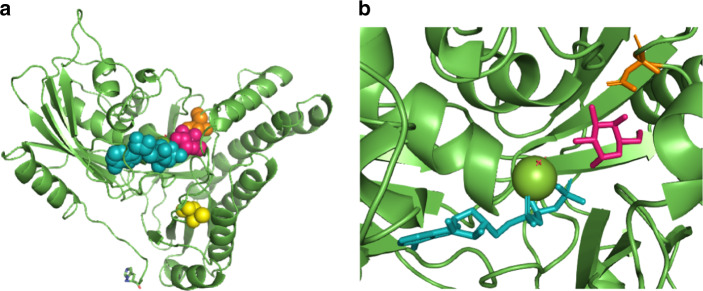

Six unpublished variants were reported, namely NM_000154.1:c.136G>A (p.Asp46Asn), NM_000154.1:c.1055C>A (p.Thr352Lys), NM_000154.1:c.700del (p.Ser234Alafs*30), NM_000154.1:c.[(?_945-7)_(*64_?)del], NM_000154.1:c.388dupG (p.Val130Gly*73), and NM_000154.1:c.510T>A (p.Cys170Ter). These unpublished variants are all rated likely pathogenic when following the criteria of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). They are all absent from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD; https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) in homozygous state, all affect highly conserved regions of the GALK1 gene, and are predicted to affect function by MutationTaster. Two of the novel genetic variants result in amino acid changes in GALK1, namely p.Asp46Asn and p.Thr352Lys (Fig. 2a). Asp46 forms part of the active site of human GALK1 where it binds galactose through C3-OH and C4-OH (Fig. 2b).5 Previous work has shown that alteration of Asp46 to alanine results in soluble, but catalytically inactive, GALK1.22 In silico prediction using PredictSNP suggested that this unpublished change in residue 46, aspartic acid to asparagine, is destabilizing (87% expected accuracy). This, combined with likely weaker binding to galactose, explains the loss of activity observed in patients. Thr352 forms part of a ß-sheet structure that has previously been implicated in controlling the specificity and activity of GALK1.23 However, no experimental studies on this residue have been reported. PredictSNP suggests that this change, threonine to lysine, is also destabilizing (87% expected accuracy). The effects of the deletions are harder to predict. Most likely, they either result in truncated, misfolded, inactive protein, or no protein at all due to nonsense mediated (messenger RNA [mRNA]) decay.

Fig. 2. The location of the two new disease-associated point variants in the human GALK1 structure.

(a) The three-dimensional structure of human GALK1 is shown in green. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (cyan) and galactose (hot pink) are shown bound in the active site. The two affected residues are shown: Asp46 (orange) and Thr352 (yellow). (b) A close-up of the active site showing how Asp46 binds, and helps orientate, the galactose molecule through C3-OH and C4-OH. The structure is based on PDB: 1WUU with gaps filled, selenomethionines converted to methionines, and AMP; PNP to ATP.5,40 Images created with PyMol.

Diet

In total, 39 patients initiated the galactose-restricted diet within the first two months of life, 12 patients beyond the second month of life, and 1 patient did not follow a diet. Data on 1 patient are missing. Thirty-five patients in whom diet was initiated within the second month of age were diagnosed following NBS (p < 0.001).

In total, 50 patients followed a galactose-restricted diet. Among these 50 patients, 12 of them were also restricted from nondairy galactose sources, defined as a strict diet.

DISCUSSION

Cataract is the constant finding in GALK1 deficiency. Other symptoms in addition to cataract were reported in the described population.

Phenotypic spectrum

In this study population, 19 of 53 patients showed cataract formation. Six of them were diagnosed with NBS and in 7 patients the diet was introduced before the second month of life (Fig. 1). Despite the introduction of a galactose-restricted diet, 4 patients developed cataract throughout childhood. This could be explained by poor diet compliance, since a galactose-restricted diet is important in preventing the development or progression of cataract. In the study population, hypoglycemia was reported in 4.3% and the presence of infection was reported in 2.0%, both comparable with the general population (5–15% and 4% respectively24,25). The occurrence of bleeding diathesis and encephalopathy in our study population were 8.1% and 3.9% respectively, thus higher than in the general population (2.17–5.9% and 0.3% respectively26,27). The data of this study showed that in 7 of the 47 patients (14.9%) with follow-up, cognitive, and/or motor developmental delay was reported. Vitrikas et al.28 described that the general prevalence of cognitive developmental delay was 1–1.5%. This information was derived from children receiving services in the United States and had been established through multiple tests (Ages and Stages Questionnaire, the Language Development Survey, and the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory). Regarding the data of our study population, 5 of the 47 patients (10.6%) were reported to have mental developmental delays. This information was based on the positive answer by the treating physician to the question in the registry, cognitive developmental delay, present or absent. No data on testing were reported. However, 2 of the 5 patients followed regular education, one followed special education while siblings followed regular education. In the other 2 patients the type of education was unknown (Table S1). Nevertheless, a difference of 10% between the GALK1 deficient patients and the general population warrants further investigation based on uniform guidelines with comparable instruments to assess the presence of cognitive developmental delay in GALK1 deficient patients.

Timson et al. described a correlation between the phenotypic spectrum of GALK1 deficiency and the biochemical consequences of specific variants. Hereby, the GALK1 phenotype was divided in three subtypes: severe, defined as the development of cataract in the newborn period; intermediate, defined as developing cataract during childhood; and mild, defined as increased cataract risk in middle age.29 Genetic variants leading to protein variants related to the severe phenotype were associated with misfolding of the GALK1 protein, since those variants produced insoluble proteins on recombinant expression in Escherichia coli (E. coli). Homozygosity for NM_000154.1:c.82C>A (p.Pro28Thr) was the most reported genotype in the study population, and this variant falls within the spectrum of a severe phenotype. On the other hand, genetic variants associated with intermediate phenotype produced soluble proteins in E. coli and showed altered kinetic aspects. A reduced turnover number was noticed in the variant NM_000154.1:c.1036G>A (p.Gly346Ser).29 Genetic variants associated with the mild phenotype are likely a genetic factor for age-related cataracts, such as the Osaka variant.30

Different variants might also lead to deficiency in different tissues. In GALK1 deficiency the occurrence of a Philadelphia variant has been described. Individuals with this variant are typically asymptomatic and show normal GALK1 activity in leukocytes and reduced GALK1 activity in erythrocytes.31 A similar phenomenon is known in classic galactosemia wherein the missense GALT variant NM_000155.3:c.404C>T (p.Ser135Leu) results in absent GALT activity in erythrocytes and 10% residual activity in other tissues as liver and leukocytes.32 In this GALT variant long-term complications are uncommon.

Other genetic, epigenetic, or environmental factors may be involved in the occurrence of other symptoms in addition to cataract in GALK1 deficient patients. These findings strongly encourage additional investigations in the future to unequivocally link or exclude these other signs and symptoms to GALK1 deficiency.

Metabolites

In general, metabolites are of enormous value for the diagnosis and for monitoring the impact of the galactose-restricted diet in galactosemias.

Hennermann et al.10 showed that initiation of diet resulted in significant decrease of urinary galactitol, without normalization of the values, in contrast to the galactose concentrations in blood that normalize with initiation of diet. Regarding our study population, normalization of urinary galactitol occurred in 2 of 18 patients for whom galactitol values were reported, indicating that urinary galactitol does not normalize in the majority of the patients after start of the diet.

A surprising finding was the reported increase of Gal-1-P value in 5 patients, returning to normal beyond the neonatal period. Theoretically, the occurrence of an elevated Gal-1-P in GALK1 deficiency seems to be unlikely. Pyhtila et al.33 also described this finding in GALK1 deficient patients screened with NBS, but related the elevated Gal-1-P to other causes that influenced liver function or the circulation rather than galactosemia. Total galactose assays were known for their nonspecificity since they measure free galactose along with galactose contributed from Gal-1-P through its reaction with alkaline phosphatase. Tandem mass spectrometry (TMS) is not capable of differentiating between different hexose monophosphates (HMP) without the use of chromatographic separation.34 Currently, more sensitive TMS with higher specificity is used for galactosemia screening that measures Gal-1-P instead of HMP with fewer false positive results. Regarding the Gal-1-P values of the above 5 patients, it is possible that these measured values were false positive due to the measurement of other sugar phosphates rather than Gal-1-P. In 3 patients, the method used to assess the Gal-1-P concentration was not described. In 1 patient the colorimetric method was employed and in the other patient, the two-step fluorometric assay. In both tests, Gal-1-P is converted to galactose. However, other sugar phosphates beside Gal-1-P can be a substrate for alkaline phosphatase, which could then lead to false positive results.35,36

Theoretically, patients with severe GALK1 deficiency on an unrestricted diet might have massive elevations in plasma and tissue galactose leading to the formation of other phosphorylated galactose compounds in hematopoietic cells thus leading to a false positive result with methodology that fails to exclusively measure Gal-1-P.

In addition to technical issues, other mechanisms might be involved. Interestingly, Gal-1-P in the neonatal period normalizing in the post neonatal period has also been described in several galactose mutarotase (GALM) deficient patients. GALM catalyzes the conversion of β-d-galactose to α-d-galactose, which enters the Leloir pathway.37

Factors influencing clinical outcome

In several countries, screening for GALK1 deficiency is implemented in the NBS program. The first GALK1 deficient patient diagnosed following NBS was described by Thalhammer et al.38 Our study showed that patients diagnosed following NBS had an early onset of a galactose-restricted diet and decreased incidence of development of cataract.

The current treatment of GALK1 deficiency consists of a lifelong galactose-restricted diet, which is recommended to prevent lenticular changes or progression of cataract later in life.15 In general, in case of severe progressed cataract, the lens could be replaced by intraocular lens implantations fabricated with polymethylmetacrylate (PMMA).13 After surgery, diet is still recommended to prevent development of secondary cataract. In addition, there is insufficient evidence that no other symptoms are related to GALK1 deficiency.

Follow-up

The data from this study showed that in 7 of the 47 patients with follow-up, developmental complications were reported. Follow-up in gonadal and bone complications were missing in the majority of the patients. Vitamin D levels assessed in only 13 patients, whose values indicated vitamin D deficiency, which is a common global health problem and therefore not necessarily related to the diet in GALK1 deficiency. Gonadal follow-up was reported in only 8 female patients and appeared normal.

The lack of follow-up in most patients exemplifies the need for guidelines on diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Our recommended clinical guideline for the management of GALK1 deficient patients would include genetic and enzymatic measurements, as well as awareness of the occurrence of neonatal complications. Periodic dietary, ophthalmological, bone, gonadal (female), and brain follow-up would also be included. The gonadal follow-up aims to identify primary ovarian insufficiency. In the brain follow-up, developmental and behavioral assessment, as well as neurological examination using validated measurements would be performed. Evaluating bone health, including assessment of calcium and vitamin D intake, physical activity, and DXA measurements would be necessary. When patients develop symptoms other than cataract, additional investigations are recommended to exclude other genetic conditions related to these symptoms. Deep phenotyping of patients with GALK1 deficiency may improve our understanding and truly clarify the phenotypic spectrum related to this entity.

Future treatments

Since aldose reductase plays a key role in the development of sugar cataracts in GALK1 deficiency, aldose reductase inhibitors could be considered as a potential therapeutic strategy.39 The inhibition of aldose reductase prevents the accumulation of galactitol as an osmotically significant polyol, and theoretically could prevent cataracts and pseudotumor cerebri in infancy. However, aldose reductase inhibitors may not address other manifestations of the disease.

Treatments to restore GALK1 enzyme activity such as pharmacological chaperones, GALK1 mRNA, and others might also be possibilities in the future.

Study limitations

The study was limited by the low prevalence of this disease, loss of follow-up in many patients, the retrospective nature of data collection, as well as nonstandardized laboratory methods and follow-up of patients in many countries.

Conclusion

We describe the phenotypic features of 53 patients with GALK1 deficiency among whom six unpublished GALK1 variants were identified. The phenotypic spectrum of GALK1 deficiency can include neonatal elevation of transaminases, bleeding diathesis, and encephalopathy in addition to cataract. NBS with timely onset of the galactose-restricted diet was beneficial for the development of cataract. A surprising phenomenon was the reported elevation of Gal-1-P values, which might be due to methodological factors (false positives) or other hexokinase activities. Potential complications beyond the neonatal period have not been systematically surveyed and additional work-up to unequivocally link other sign and symptoms to the GALK1 deficiency is missing, leaving the impact of GALK1 deficiency questionable and indicating a need to improve diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of these patients.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Crushell, C. De Laet, A. Nuoffer, and N. Vanhoutvin for their help in entering data in the GalNet registry. We thank R. Vos for his help in the statistical analysis. We thank R. Dalgleish for his help in validating the descriptions of the DNA variants. This work was financially supported by several foundations. A grant from The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NOW) to M.E.R.-G. financed the GalNet meeting to discuss the registry. The Dutch Galactosemia Research foundation, European Galactosemia Society and Metakids grants to M.E.R.-G. financially supported the development, implementation, maintenance, and analysis of the GalNet registry. The coordinating center did the data entry of all galactosemia patients for 6 of the 7 participating Dutch centers and was financially supported by a Stofwisselkracht grant to M.E.R.-G. Stofwisselkracht and Metakids grant to M.E.R.-G. financially supported the analysis and interpretation of the data. A national Health Research Board (HRB) grant to E.P.T. financed the development of the registry in Ireland. Data entry for the patients from Switzerland was financially supported by a grand from the Batzebär foundation of the University Hospital Bern to M.G. and by the Galactosämie Schweiz patient organization. Data entry for the patients from Spain was financed by the Spanish Galactosemia foundation. eCRFs development for data entry: M.E.R.-G., A.M.B., E.P.T., M.G., G.T.B. Implementation and Coordination of registry: M.E.R.-G. Financial support grant writing for design, implementation, maintenance of the registry: M.E.R.-G. Those responsible for obtaining ethical approval at the different centers, informed consent from patients, collecting medical data and entry of the data: M.E.R.-G., B.D., A.M.D., U.M., D.M., M.L.C., A.E., C.F., N.J.P., M.M.L.S.-P., I.A.R., S.S.B., A.M.B., D.C., D.D., M.G., I.K., P.L., A.S., P.V., S.B.W., E.P.T., D.J.T., G.T.B.. Curation of data: M.E.R.-G. Data analysis and interpretation: M.E.R.-G., B.D. Manuscript writing: M.E.R.-G., B.D., D.D., D.J.T., G.T.B. Manuscript editing and final approval: all authors.

Disclosure

A.M.B. has been a member of advisory boards for Nutricia and Biomarin and has received a speaking fee. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Shared senior authors: David J. Timson, Gerard T. Berry

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/11/2020

The original online PDF version of the Article presented Figure 2 in monochrome. It now appears in colour in both the PDF and HTML versions of the Article. The original HTML version of the Article did not acknowledge its publication under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. The HTML version of the Article has now been updated.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41436-020-00942-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Kalaydjieva L, Perez-Lezaun A, Angelicheva D, et al. A founder mutation in the GK1 gene is responsible for galactokinase deficiency in Roma (Gypsies) Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1299–1307. doi: 10.1086/302611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanconi G. Marked galactose intolerance (galactose diabetes) in a child with neuronbromatosis Eecklinghausen. Jahrb Kinderheilkd. 1933;138:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gitzelmann R. Deficiency of erythrocyte galactokinase in a patient with galactose diabetes. Lancet. 1965;2:670–671. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(65)90400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timson DJ. The molecular basis of galactosemia—past, present and future. Gene. 2016;589:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thoden JB, Timson DJ, Reece RJ, Holden HM. Molecular structure of human galactokinase: implications for type II galactosemia. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9662–9670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sneha P, Ebrahimi EA, Ghazala SA, et al. Structural analysis of missense mutations in galactokinase 1 (GALK1) leading to galactosemia type-2. J Biol Chem. 2018;119:7585–7598. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jójárt B, Szori M, Izsák R, et al. The effect of a Pro28Thr point mutation on the local structure and stability of human galactokinase enzyme-a theoretical study. J Mol Model. 2011;17:2639–2649. doi: 10.1007/s00894-011-0958-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gitzelmann R, Steinmann B. Galactosemia: how does long-term treatment change the outcome. Enzyme. 1984;32:37–46. doi: 10.1159/000469448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Ptolemy AS, Harmonay L, Kellogg M, Berry GT. Ultra fast and sensitive liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry based assay for galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase and galactokinase deficiencies. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;102:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennermann JB, Schadewaldt P, Vetter B, Shin YS, Monch E, Klein J. Features and outcome of galactokinase deficiency in children diagnosed by newborn screening. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fridovich-Keil JL, Walter JH. Galactosemia. In: Valle D, Beaudet A, Vogelstein B, Kinzler BW, Antonarakis SE, Ballabio A, Scriver CR, editors, The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (9th ed.), Chapter 72. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

- 12.Ai Y, Zheng Z, O’Brien-Jenkins A, et al. A mouse model of galactose-induced cataracts. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1821–1827. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.12.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khurana A. Comprehensive ophthalmology. 4th ed. New Delhi: New Age International; 2007.

- 14.Kinoshita JH. Cataracts in galactosemia. The Jonas S. Friedenwald Memorial Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol. 1965;4:786–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stambolian D. Galactose and cataract. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32:333–349. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huttenlocher PR, Hillman RE, Hsia YE. Pseudotumor cerebri in galactosemia. J Pediatr. 1970;76:902–905. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(70)80373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosch AM, Bakker HD, van Gennip AH, van Kempen JV, Wanders RJ, Wijburg FA. Clinical features of galactokinase deficiency: a review of the literature. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2002;25:629–634. doi: 10.1023/A:1022875629436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubio-Gozalbo ME, Bosch AM, Burlina A, Berry GT, Treacy EP, Steering Committee on behalf of all Galactosemia Network representatives. The galactosemia network (GalNet) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40:169–170. doi: 10.1007/s10545-016-9989-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubio-Gozalbo ME, Haskovic M, Bosch AM, et al. The natural history of classic galactosemia: lessons from the GalNet registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:86. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendl J, Stourac J, Salanda O, et al. PredictSNP: robust and accurate consensus classifier for prediction of disease-related mutations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett DA. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25:464–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Timson DJ, Reece RJ. Sugar recognition by human galactokinase. BMC Biochem. 2003;4:16–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kristiansson H, Timson DJ. Increased promiscuity of human galactokinase following alteration of a single amino acid residue distant from the active site. Chembiochem. 2011;12:2081–2087. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hay WW, Jr, Raju TN, Higgins RD, Kalhan SC, Devaskar SU. Knowledge gaps and research needs for understanding and treating neonatal hypoglycemia: workshop report from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. J Pediatr. 2009;155:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha A, Yokoe D, Platt R. Epidemiology of neonatal infections: experience during and after hospitalization. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:244–251. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000055060.32226.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasbaoui BE, Karboubi L, Benjelloun BS. Newborn haemorrhagic disorders: about 30 Cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:150. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.150.13159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aslam S, Strickland T, Molloy EJ. Neonatal encephalopathy: need for recognition of multiple etiologies for optimal management. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:142. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vitrikas K, Savard D, Bucaj M. Developmental delay: when and how to screen. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timson DJ, Reece RJ. Functional analysis of disease-causing mutations in human galactokinase. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1767–1774. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okano Y, Asada M, Fujimoto A, et al. A genetic factor for age-related cataract: identification and characterization of a novel galactokinase variant, “Osaka,” in Asians. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1036–1042. doi: 10.1086/319512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soni T, Brivet M, Moatti N, Lemonnier A. The Philadelphia variant of galactokinase in human erythrocytes: physicochemical and catalytic properties. Clin Chim Acta. 1988;175:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(88)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai K, Langley SD, Singh RH, Dembure PP, Hjelm LN, Elsas LJ., 2nd A prevalent mutation for galactosemia among black Americans. J Pediatr. 1996;128:89–95. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyhtila BM, Shaw KA, Neumann SE, Fridovich-Keil JL. Newborn screening for galactosemia in the United States: looking back, looking around, and looking ahead. JIMD Rep. 2015;15:79–93. doi: 10.1007/8904_2014_302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen AS. Including classical galactosaemia in the expanded newborn screening panel using tandem mass spectrometry for galactose-1-phosphate. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2019;5:19. doi: 10.3390/ijns5020019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diepenbrock F, Heckler R, Schickling H, Engelhard T, Bock D, Sander J. Colorimetric determination of galactose and galactose-1-phosphate from dried blood. Clin Biochem. 1992;25:37–39. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(92)80043-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gitzelmann R. Estimation of galactose-I-phosphate in erythrocytes: a rapid and simple enzymatic method. Clin Chim Acta. 1969;26:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(69)90385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wada Y, Kikuchi A, Arai-Ichinoi N, et al. Biallelic GALM pathogenic variants cause a novel type of galactosemia. Genet Med. 2019;21:1286–1294. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thalhammer O, Gitzelmann R, Pantlitschko M. Hypergalactosemia and galactosuria due to galactokinase deficiency in a newborn. Pediatrics. 1968;42:441–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kador PF. The role of aldose reductase in the development of diabetic complications. Med Res Rev. 1988;8:325–352. doi: 10.1002/med.2610080302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAuley M, Huang M, Timson DJ. Insight into the mechanism of galactokinase: Role of a critical glutamate residue and helix/coil transitions. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins and Proteomics. 2017;1865:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.