Abstract

Background:

Exosomes isolated from plasma of lung transplant recipients (LTxRs) with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) contain human leukocyte antigens and lung self-antigens (SAgs), K-alpha 1 Tubulin (Kα1T) and Collagen-V (Col-V). The aim was to determine the use of circulating exosomes with lung SAgs as a biomarker for BOS.

Methods:

Circulating exosomes were isolated retrospectively from plasma, at diagnosis of BOS, at 6 and 12 months prior to the diagnosis (N=41) and stable (time matched controls) (N=30) from LTxRs at two transplant centers by ultracentrifugation. Exosomes were validated using Nanosight and lung SAgs (Kα1T and Col-V) detected by immunoblot and semi-quantitated using ImageJ software.

Results:

Circulating exosomes from BOS and stable LTxRs demonstrated 61–181nm vesicles with markers Alix and CD9. Exosomes from LTxRs with BOS (N=21) showed increased levels of lung SAgs compared to stable (N=10). A validation study using two separate cohorts of LTxRs with BOS and stable (time-matched controls) from two centers also demonstrated significantly increased lung SAgs containing exosomes at 6 and 12 months prior to BOS.

Conclusion:

Circulating exosomes isolated from LTxRs with BOS demonstrated increased levels of lung SAgs (Kα1T and Col-V) 12 months prior to the diagnosis (100% specificity and 90% sensitivity) indicating that circulating exosomes with lung SAgs can be used as a non-invasive biomarker for identifying LTxRs at risk for BOS.

Introduction

The development of chronic rejection following solid organ transplantation is a major barrier for continued function of the transplanted organ. Once chronic rejection develops, there are no treatment options available to reverse the process. Among transplanted organs, chronic rejection is most common following human lung transplantation (LTx), where the five year incidence is approximately 50% and nearly 90% develop chronic rejection within 10 years.1 Lung allograft failure, due to chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), is the leading cause of death beyond the first year after transplantation.2 Approximately 70% of patients with CLAD have bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS),3, 4 a fibrotic obliteration of respiratory and membranous bronchioles.5–7 Histologic confirmation of BOS is often difficult because surgical lung biopsy is invasive and carries unacceptable risk. In addition, the sensitivity of transbronchial lung biopsy is poor because of the limited sample size and the patchy involvement of respiratory and membranous bronchioles.8 Therefore, BOS, diagnosed and staged according to changes in spirometry, was developed as clinical surrogate for obliterative bronchiolitis.6, 7 Nonetheless, it is recognized that changes in spirometry are downstream of the pathogenic injury that results in the small airway fibrosis. Although a decrement in small airway forced expiratory flow (FEF25–75%) may presage the decrement in forced expiratory volume (FEV1), this lacks specificity for BOS.7, 9 It has been reported that bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and its cell transcriptome may serve as biomarker for BOS.10, 11 Thus, there is a clinical need for a biomarker that predicts the development of BOS at an early stage to enhance monitoring and provide an opportunity for intervention.

Our laboratory demonstrated that circulating exosomes isolated from plasma and BAL from LTx recipients (LTxRs) with BOS are from the donor and have donor human leukocyte antigens and expressed Kα1Tubulin (Kα1T) and Collagen type V (Col-V), the prototypic lung self-antigens (SAgs).12, 13 Another report have shown the presence of exosomes in BAL of LTxRs with acute and chronic rejection.14 Therefore, we hypothesized that detection of circulating exosomes containing lung SAgs prior to the diagnosis of BOS would serve as a biomarker for identifying LTxRs at risk for BOS.

Methods

Sample collection

Seventy-one LTxRs were selected from Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) and University of Washington, Seattle (UW). This is a retrospective study based on collected plasma samples and clinical information. We obtained institutional review board approval from all centers and consent from all subjects for this study. Among these, 41 were diagnosed with BOS, 30 did not have BOS (control/stable group). For the discovery cohorts, 21 samples with BOS and 10 stable (time matched control) were used. For the validation cohorts, plasma from 20 BOS LTxRs and 20 stable/control LTxRs from WUSM and UW (10 from each) was collected at 6 and 12 months and at the time of BOS after LTx. All the plasma collected for LTxRs with BOS were time matched with the stable/control LTxRs.

We diagnosed BOS according to the standard ISHLT criteria.15, 16 Specifically, our clinical approach to allograft dysfunction includes a thorough evaluation of potential causes (e.g., acute cellular rejection, infection, antibody-mediated rejection, bronchostenosis) including a history and physical exam, imaging studies, nasopharyngeal swab for the detection of respiratory viruses, DSA test, and bronchoscopy with BAL and transbronchial lung biopsies. We then confirm the diagnosis of CLAD in cases where there is a persistent ≥ 20% decline in FEV1 without an alternative explanation for more than 3 months. CLAD phenotype was based on forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1, and the presence or absence of radiographic infiltrates on imaging. In this cohort study, we did not have sufficient total lung capacity measurements as this has not been part of our routine follow-up of patients. Thus, we excluded restrictive allograft syndrome by using FVC, FEV1/FVC ratio, and chest imaging. We treated cases where we identified an alternate explanation for allograft dysfunction (e.g., appropriate antibiotics for a bacterial bronchitis) and only made a diagnosis of CLAD if there was a persistent ≥ 20% decline in FEV1 in spite of appropriate therapy for more than 3 months.

Isolation of exosomes

Circulating exosomes were isolated from plasma using ultracentrifugation as described previously.12 Plasma (1ml) was centrifuged at 2000g for 30 min then 10000g for 40 min at 4°C, supernatant was diluted with PBS and centrifuged at 100000g for 120 mins at 4°C. When there was plasma less than 100μl, total exosomes isolation kit was used as described by manufacturer (Invitrogen) with modifications including passing through a 0.2μm filter. Comparison of these two approaches provided similar results in Nanosight and lung SAg measurements. Exosome pellet was suspended in PBS and concentration of protein was analyzed using BCA. Isolated exosomes were subjected to Nanosight NS300 instrument (Malvern Instruments, UK) to analyze size distribution. Exosomes were diluted in PBS (1:50 dilution), their size was verified and the exosomes used in this study had the range between 40–200nm.

Western blot analysis

To analyze the presence of lung SAgs in exosomes, we performed western blot. 10μg of protein was used for SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membrane. Antibodies (Abs) to SAgs, anti-rabbit Col-V (Abcam) and anti-rabbit Kα1T (Santa Cruz) IgG were used to detect protein. Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as secondary Abs. Blot was developed using enhanced chemiluminescent detection kit. J Image Software (NIH) used for densitometry of the signal band.

Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis

Results obtained for the fold change from the Western blot analysis for lung SAgs containing exosomes, ROC determination was performed by GraphPad Prism version 7 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA). The cut off values were determined from the discovery cohort for lung SAgs with 21 patients with BOS and 10 stable control (time matched control LTxRs) at 6 and 12 months prior to clinical diagnosis of BOS. The validation cohort was from 20 BOS LTxRs and 20 control LTxRs from WUSM and UW (10 from each center) at 6 and 12 months before development of BOS after LTx.

Statistical analysis

Optical density of exosome containing lung SAgs was quantitated using ImageJ software. The optical density of SAgs were normalized with exosome specific marker Alix and CD9 and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The relative OD values for SAgs between BOS and stable LTxRs were compared using unpaired and paired non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. The two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare normalized level of each antigen between patients diagnosed with chronic rejection and patients with stable/control condition at 6 and 12 months. Bonferroni correction was utilized to adjust for multiple comparisons, so significance level of 0.0125 was used for each test (two antigens and two time points). The same procedure was repeated for the validation data. GraphPad Prism version 7 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA) was used to perform the analysis.

Results

Clinical data of LTxRs

LTxR demographics and laboratory data of the discovery cohort (n=31) were collected from patient charts. BOS was diagnosed according to International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines.17 Patient demographics including age, gender, ethnicity, and underlying diagnosis were not significantly different between LTxRs with BOS and stable (time matched controls) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Discovery Studies: Demographic of Lung Transplant Recipients

| Characteristics | Stable (years) 2000–2015 |

BOS (years) 2002–2015 |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 21 |

| Sex (N and %) | ||

| - Male | 7 (70%) | 15 (71.4%) |

| - Female | 3 (30%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| - Age (Y) Mean ± SD | 53.8 ± 8.0 | 50.7 ± 14.1 |

| Ethnicity (N and %) | ||

| - Caucasians | 10 (100%) | 21 (100%) |

| - Black | 0 | 0 |

| - Bilateral Transplat | 10 | 21 |

| Disease (N and %) | ||

| - Cystic Fibrosis | 2 (10%) | 8 (31%) |

| - IPF | 3 (50%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| - COPD | 4 (30%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| - BOS | 0 | 1 (4.8%) |

| - Interstitial lung disease | 0 | 1 (4.8%) |

| - MCTD | 1 (10%) | 0 |

Definitions of abbreviations: IPF: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BOS: Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease

Size distribution and characterization of exosomes

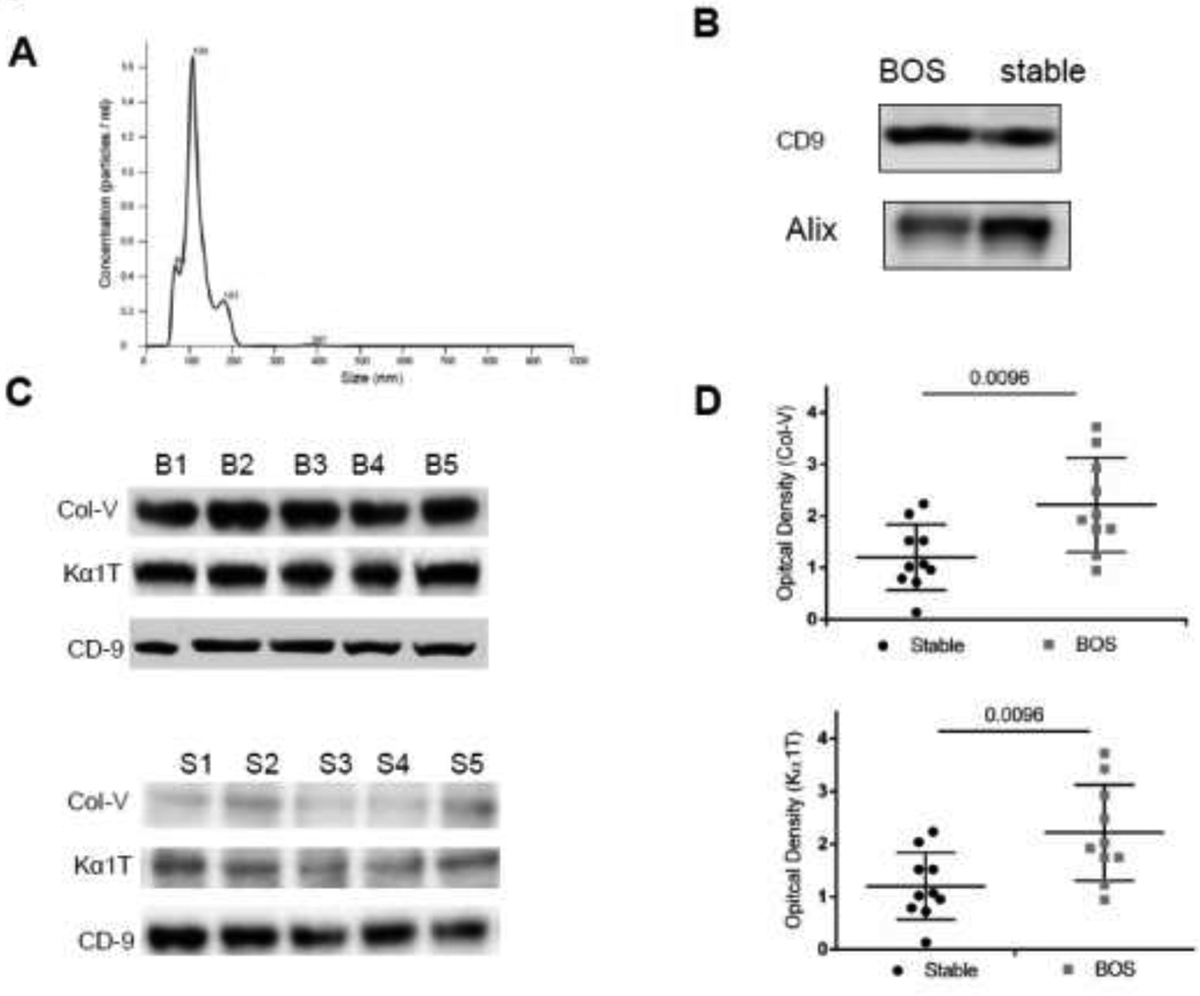

Size distribution of isolated exosomes from LTxRs was carried out using Nanosight NS300. As shown in figure 1A, the vesicles size used in this study ranged from 61–181nm, compatible with exosomes as described in a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles.18 Western blot analysis also showed the presence of exosome markers Alix and CD9 (figure 1B). These results confirm that the isolated vesicles are exosomes.

Figure 1:

(A) Exosomes were isolated from plasma by ultracentrifugation, diluted in PBS and subjected to NanosightNS300 analysis and results demonstrated that the extracellular vesicles has size of 60–200 nM. Similar results were also obtained using the modified kit method. (B) Western blot analysis showed presence of exosomes markers CD9, Alix in exosomes isolated from plasma of stable and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) patients. (C) Exosomes isolated from plasma from a different center (UW) at the time of BOS diagnosis contain Collagen V (Col-V) and Kα1 Tubulin (Kα1T): Exosomes were isolated from plasma of lung transplant recipients (LTxRs) from University of Washington (different center) diagnosed with BOS (n=10) and stable (time match control) (n=10) and subjected to western blot analysis for the detection of lung self-antigens. Western blot analysis of representative 5 BOS and 5 stable showed: increased amount of Col-V and Kα1T in exosomes derived from BOS LTxRs but not in stable. Representation depicts 5 out of 10 LTxRs from BOS (top) and stable (bottom). (D) Semi quantification by densitometry showed significant increase in optical density for Col-V (top) and Kα1T (bottom) in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) lung transplant recipients when compared with stable.

Increased levels of circulating exosomes with lung SAgs in LTxRs diagnosed with BOS

Previous studies demonstrated that exosomes isolated from the LTxRs with BOS contained lung SAgs (Col-V, Kα1T).12, 19 To confirm our earlier findings, we isolated exosomes from plasma of LTxRs with BOS from a different LTx center (UW) and observed similar results, ie, circulating exosomes from BOS LTxRs contained increased levels of Col-V (2.09±1.06 vs 1.17±0.66, p=0.0096; 1.79 fold) and Kα1T (2.10±1.16vs1.19±0.67, p=0.0096; 1.76 fold) in comparison to stable (time matched controls) (figure 1D). Western blot from 5 BOS and 5 stable are given in figure 1C. This result corroborates our previous findings.12, 19

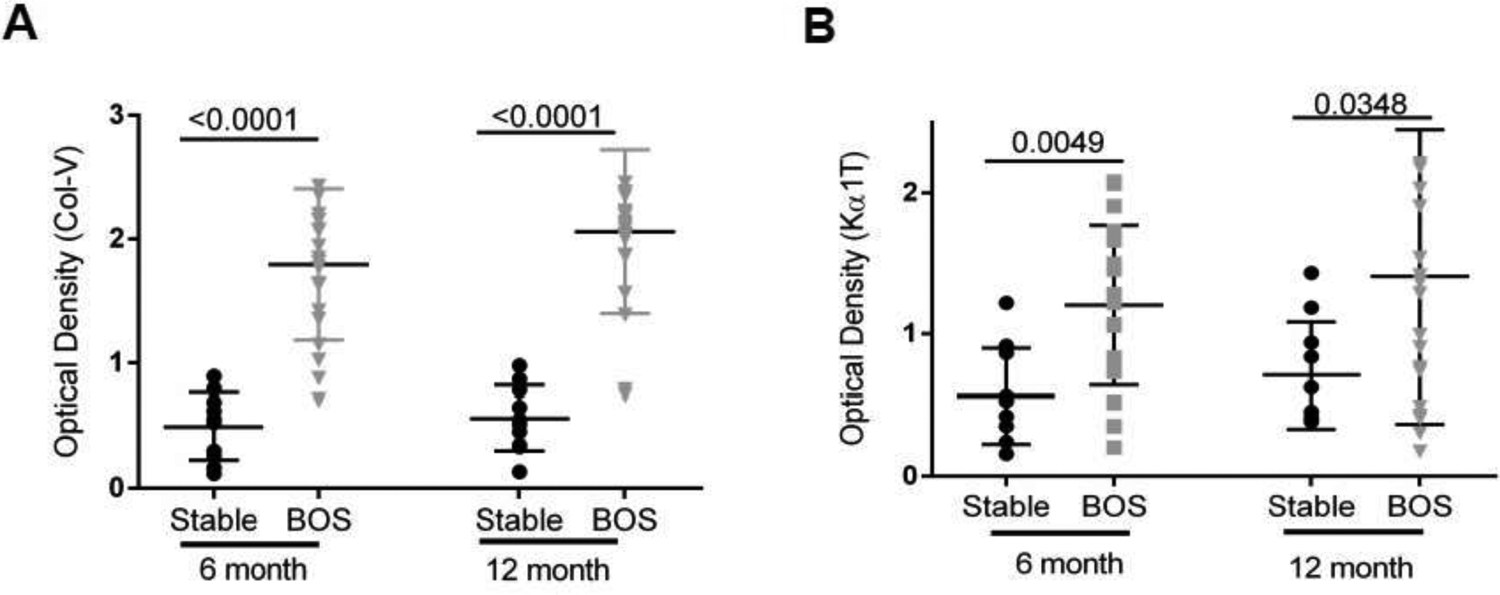

Detection of circulating exosomes with lung SAg, Col-V, 12 months prior to the diagnosis of BOS

To determine whether circulating exosomes were detectable prior to the clinical diagnosis of BOS, we isolated exosomes from plasma collected from 21 LTxRs with BOS and 10 stable (time matched control LTxRs) at 6 and 12 months prior to the diagnosis of BOS (“discovery cohort”). Western blot results shown in figure S1A demonstrate that exosomes from LTxRs contained significantly higher levels of Col-V at 6 and 12 months prior to BOS. Semi-quantitation by densitometry demonstrated significantly higher levels of lung SAgs at 6 months (1.79±0.59 vs 0.49±0.27, p<0.0001; 3.65 fold) and 12 months (2.06±0.65 vs 0.56±0.26, p<0.0001; 3.67 fold) in the exosomes isolated from LTxRs with BOS compared to matched stable (figure 2A). We also assessed the amount of Kα1T in exosomes using western blot (.figure S1B). Results of semi-quantitation of the gels demonstrate that exosomes from LTxRs with BOS contained significantly increased levels of Kα1T (figure 2B) compared to stable, both at 6 months (1.20±0.55 vs 0.56±0.34, p=0.0049; 2.14 fold) and 12 months (1.41±1.02vs 0.71±0.37, p=0.0348; 1.99 fold) prior to BOS. These results demonstrate that circulating exosomes containing significantly increased levels of both lung SAgs (Kα1T, Col-V) are present in LTxRs with BOS compared to stable (time matched controls) up to 12 months before the diagnosis of BOS.

Figure 2:

Analysis of exosomes isolated from circulation of 21 BOS LTxR and 10 time matched stable LTxR (Discovery Cohort) (A). Semi-quantification by densitometry revealed significant increase in Col-V optical density in comparison to stable, 6 month (1.79±0.59 vs 0.49±0.27, p<0.0001) and 12 month (2.06±0.65 vs 0.56±0.26, p<0.0001). (B) Densitometry analysis showed significantly increased Kα1T optical density when compared with stable, 6 month (1.20±0.55 vs 0.56±0.34, p=0.0049) and 12 month (1.41±1.02 vs 0.71±0.37, p=0.0348). Western blot data is presented in Supplementary figure S1.

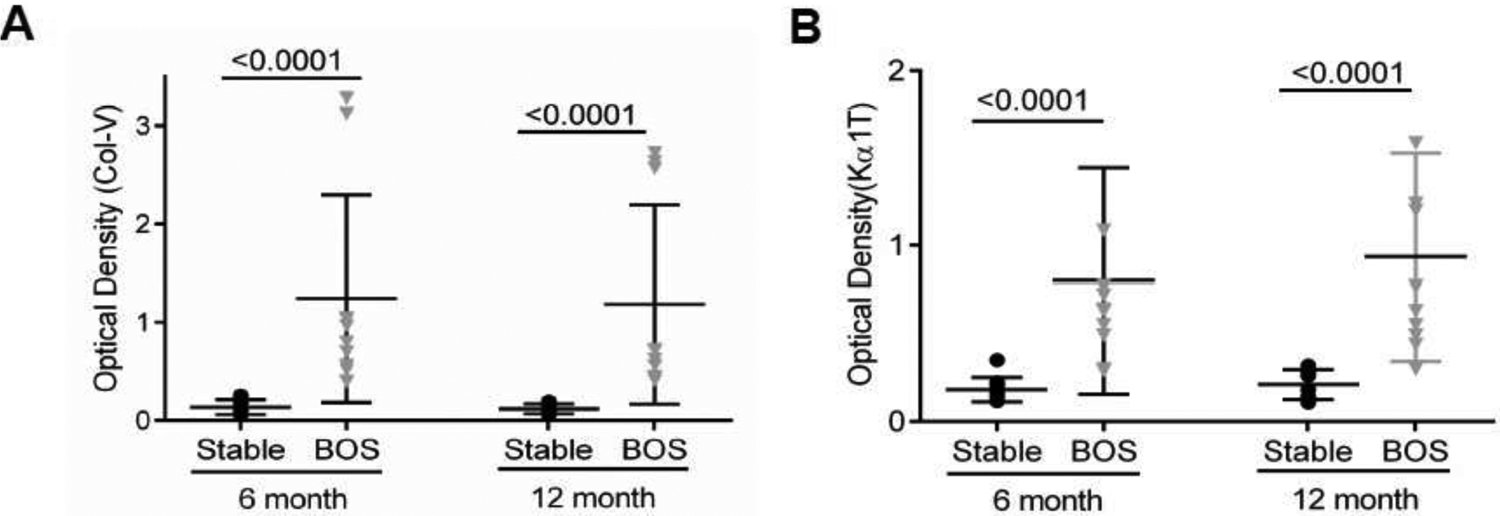

Validation using different cohort of BOS patients

To validate the results obtained in the preliminary analysis indicating that circulating exosomes with increased levels of SAgs could identify patients at increased risk for BOS, we analyzed circulating exosomes from independent cohorts of LTxRs consisting of 10 with BOS and 10 stable/control from WUSM. Demographics of LTxRs used in this study are given in Table 2. Plasma collected at 6 and 12 months prior to BOS and time-matched samples from stable LTxRs without BOS. In agreement with our preliminary results, western blot results of exosomes isolated from BOS patients demonstrated significantly higher levels of lung SAgs compared with stable LTxRs (figure S2). Semi-quantitation by densitometry corroborated western results (6 months, Col-V, 1.24±1.06 vs 0.13±0.07, 9.54 fold p<0.0001; Kα1T 0.80±0.64 vs 0.18±0.07; 4.44 fold, p<0.0001) and 12 months (optical density, Col-V, 1.18±1.02 vs 0.12±0.05, p<0.0001 9.83 fold; Kα1T 0.94±0.59 vs 0.21±0.09, p<0.0001, 4.48 fold) (figure 3A& B).

Table 2.

Validation Studies: Demographic of a Different Cohort of Lung Transplant Recipients from Washington University School of Medicine and University of Washington

| WUSM samples | UW Samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Stable (years) 2008–2013 |

BOS (years) 2003–2013 |

Stable (years) 2008–2012 |

BOS (years) 2007–2012 |

| Number | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Sex (N and %) | ||||

| - Male | 6 (60%) | 7 (70%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) |

| - Female | 4 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) |

| - Age (Y) Mean ± SD | 51.3±10.2 | 54.3±15.4 | 53.8±13.8 | 50.7±11.3 |

| Ethnicity (N and %) | ||||

| - Caucasians | 8 (80%) | 10 (100%) | 9 (90%) | 9 (90%) |

| - Black | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) |

| - Bilateral Transplant | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Disease (N and %) | ||||

| - Cystic Fibrosis | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 3 (30%) |

| - IPF | 3 (30%) | 3 (30%) | 1 (10%) | 5 (50%) |

| - COPD | 3 (30%) | 3 (30%) | 6 (60%) | 2 (20%) |

| - Alpha 1 | 1 (10%) | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0 |

| - Sarcoidosis | 0 | 2 (20%) | 0 | 0 |

| - Scleroderma | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0 | 0 |

| - PCH | 1 (10%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| -Interstitial lung disease | 0 | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0 |

Definitions of abbreviations: BOS: bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPF: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; PCH: Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis

Figure 3:

.Analysis of circulating exosomes for lung SAgs from a different LTxRs center (WUSM) (Validation cohort) consisting of 10 with BOS and 10 stable/control demonstrating increased levels of lung SAgs containing exosomes 6 and 12 months prior to clinical diagnosis of BOS. Densitometry analysis demonstrate that exosomes isolated from BOS patients has increased lung self-antigens, (Optical Density, Collagen V (Col-V) (A), 6 month 1.24±1.06 vs 0.13±0.07, p<0.0001; 12 months 1.18±1.02 vs .0.12±0.05, p<0.0001 (B) (Optical density Kα1 Tubulin (Kα1T) 6 months 0.80±0.64 vs 0.18±0.07, p<0.0001) and; 12 months 0.94±0.59 vs 0.21±0.09, p<0.0001). Western blot results are presented in Supplementary figure S2.

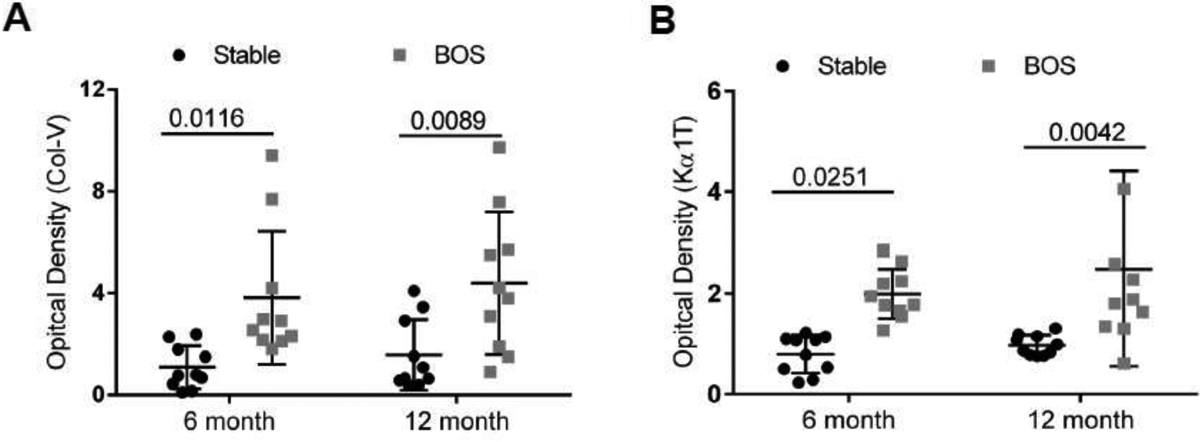

Further, to revalidate our findings, we isolated circulating exosomes from plasma in 10 LTxRs with BOS and 10 stable (time matched controls) from UW. Demographics of LTxRs used for this study from UW are given in Table 2. Plasma was collected at 6 and 12 months before BOS. We observed similar results in western blot for lung SAgs; the presence of exosomes containing lung SAgs 12 months prior to the diagnosis of BOS compared with stable (figure S3), Semi-quantitation of the western showed Col-V (6 months: 3.8±2.6 vs 1.09±0.84; p=0.0116, 3.21 fold; 12 months: 4.39±2.79 vs 1.57±1.39, p=0.0089, 2.8 fold) and Kα1T (6 months: 2.00±0.49 vs 0.080±0.37, p=0.025 1.25 fold; 12 months: 2.48±1.92 vs 0.98±0.19, p=0.0042, 2.53 fold) (figure 4A& B). These results validate the results from the discovery cohort using two separate set of LTxRs from two different centers and provide evidence that circulating exosomes containing increased lung SAgs can be detected in plasma up to 12 months before the diagnosis of BOS.

Figure 4:

Analysis of circulating exosomes for lung SAgs from a different LTxRs center ( UW) (Validation cohort) consisting of 10 with BOS and 10 stable/control demonstrating increased levels of lung SAgs containing exosomes 6 and 12 months prior to clinical diagnosis of BOS. Exosomes isolated from plasma of BOS had significantly increased levels of lung self-antigens in comparison to stable. Semi quantification analysis of optical density of Collagen V (Col-V). (A) (6 month: 3.8±2.6 vs 1.09±0.84; p=0.0116, 12 month: 4.39±2.79 vs 1.57±1.39 p=0.0089), Kα1 Tubulin (Kα1T). (B) (6 month: 2.00±0.49 vs 0.080±0.37; p=0.0251, 12 month: 2.48±1.92 vs 0.98±0.19 p=0.0042. Western blot results are presented in Supplementary figure S3.

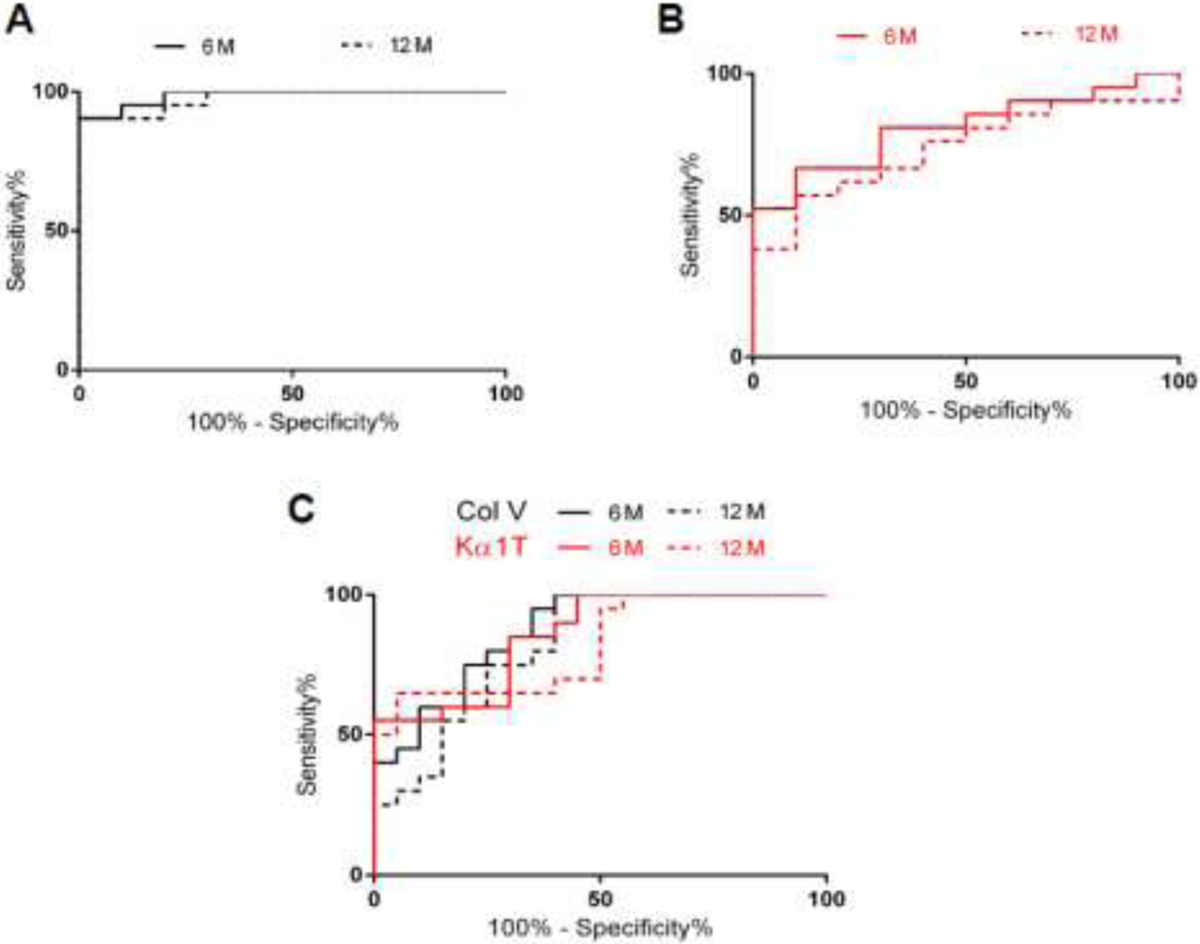

Sensitivity and specificity analysis

ROC analysis of lung SAgs (Col-V, Kα1T) for the discovery cohort (figure 5A&B) and validation cohort (figure 5C) were performed at 6 and 12 months prior to BOS. In the discovery cohort, Col-V levels at 6 months (Area under curve; AUC=0.99) showed sensitivity of 85.71% and specificity of 100% at a cut off fold change of >1.09. Col-V levels at 12 months (AUC=0.98) showed a sensitivity of 90.48% and a specificity of 100% at a cutoff fold change of >1.18. Kα1T levels at 6 months (AUC=0.81) and 12 months (AUC=0.74) showed sensitivity of 61.9% (6 months); 57.14% (12 months) and specificity of 90% (6 months); 80% (12 months) at cutoff of >1.06 for 6 months and >1.09 for 12 months respectively. The cutoff values for validation cohort was determined based on the discovery cohort. The validation cohort revealed that Col-V levels at 6 months (AUC=0.87) showed sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 80% at cutoff of >0.99. Col-V levels at 12 months (AUC=0.82) showed sensitivity of 60% and a specificity of 75% at cutoff of >0.99. Kα1T levels at 6 months (AUC=0.85) and 12 months (AUC=0.82) showed a sensitivity of 60% (6 months); 65% (12 months) and a specificity of 80% (6 months); 80% (12 months) at cutoff of >1.07 for 6 months and >1.04 for 12 months respectively (Table 3).

Figure 5.

(A) Receiver operating curve (ROC) were calculated for circulating exosomes with lung self-antigen (SAg), Collagen V (Col-V), at two time points (6 and 12 months) in discovery cohort to determine optimum threshold values. Col-V levels at 6 months (—) had an area under curve (AUC) AUC=0.99 and 12 month (- - -) (AUC=0.98). (B) ROC was calculated for circulating exosomes with lung SAg, Kα1 Tubulin (Kα1T), at two time points (6 and 12 months) in discovery cohort to determine optimum threshold values. Kα1T levels had an AUC at 6 months (0.81) and 12 month (0.74). (C) Validation Cohort; ROC were calculated for circulating exosomes with lung SAgs at two time points (6 and 12 months) for combined validation cohorts from both centers (Washington Univ. School of Medicine and Univ. Washington-Seattle). Validation cohort revealed that Col-V levels at 6 months had AUC=0.87 and at 12 month (AUC=0.82) (black). Kα1T levels at 6 months had an AUC=0.85 and 12 months (AUC=0.82) respectively (Red).

Table 3.

Statistical Analysis of Lung Self-Antigens for Discovery and Validation cohorts

| Discovery Cohort | Validation Cohort | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Time | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| SAgs | Points (months) | AUC | Cut-off | (%) | (%) | AUC | Cut-Off | (%) | (%) |

| Col-V | 6 | 0.99 | >1.09 | 85.71 | 100 | 0.87 | >0.99 | 70 | 80 |

| 12 | 0.98 | >1.18 | 90.48 | 100 | 0.82 | >0.99 | 60 | 75 | |

| Kα1T | 6 | 0.81 | >1.06 | 90 | 0.85 | >1.07 | 60 | 80 | |

| 12 | 0.74 | >1.09 | 57.14 | 80 | 0.82 | >1.04 | 65 | 80 | |

Definition of abbreviation: AUC: area under curve; SAgs: self-antigens; Col-V: Collagen V; Kα1T: Kα1 Tubulin

Western blotting results obtained from both centers were analyzed in the validation cohort and their sensitivity and specificity were determined to predict exosomes with increased lung SAgs in LTx population studied. The values obtained from the validation cohorts, though significant, were not similar to that obtained for the discovery cohort likely due to smaller number of LTxRs analyzed for validation as well as potential differences in the diagnostic criterion between the two centers.

Discussion

Using rigorous study design (discovery and validation cohorts) we have demonstrated that circulating exosomes containing increased levels of lung SAgs (Kα1T, Col-V) are present, not only at the time of BOS diagnosis, but also preceding the diagnosis, and might, therefore, be useful for predicting the development of BOS in LTxRs. Our results demonstrate that plasma collected at 6 and 12 months, prior to the diagnosis of BOS, have significantly increased levels of circulating exosomes with lung SAgs. This may allow the development of strategies for prevention and/or early treatment of LTxRs who are at risk for developing BOS.

Our group and others have demonstrated that development of Abs to mismatched donor human leukocyte antigens and immune responses to lung SAgs (Col-V)20 are associated with the development of primary graft dysfunction21 (PGD) and BOS22–24. PGD and respiratory viral infections (RVI) are widely recognized risk factors for BOS.25–28 Based on these, we propose that stress to the transplanted organs either by PGD, RVI, or rejection can release circulating exosomes with lung SAgs. Persistence of stress may continue to induce and release the exosomes with lung SAgs into the circulation which can lead to immune activation, increasing the risk of BOS. Therefore, circulating exosomes with lung SAgs could serve as a non-invasive biomarker for identifying LTxRs at risk for developing BOS. We recently demonstrated the presence of lung SAgs in circulating exosomes isolated from LTxRs diagnosed with PGD, RVI, acute rejection, and following de novo development of Abs specific to donor mismatched HLA.29 These exosomes also contain immunoregulatory proteins including transcription factors, adhesion and co-stimulatory molecules and 20S proteasome. Immunization of mice with exosomes from LTxRs with BOS induced cellular and humoral immune responses to lung SAgs strongly suggesting that these exosomes are immunogenic.30 Thus, the detection of increased lung SAgs-containing exosomes is not only might serve as a non-invasive biomarker for injury but also their persistence may increase immune responses that result in chronic rejection. Studies from our laboratory have shown that lung injury due to PGD, acute rejection, and respiratory viral infections, known risk factors for the development of CLAD also induces circulatory exosomes with lung SAgs and preliminary studies have shown that persistence of these exosomes with lung SAgs leads to development of Abs to mismatched donor HLA antigens (DSA), a known risk factor for the development of CLAD.29, 30 Therefore, removal of the circulating exosomes with lung SAgs by plasmapheresis may reduce the development of DSA which may result in increases in the freedom from development of CLAD. We also propose that early institution of extracorporal photopheresis (ECP) treatment, which is currently provided as a treatment option for LTxRs diagnosed with BOS, need to be carried out when circulating exosomes with increased lung SAgs are detected early, ie, 6–12 months prior to clinical diagnosis of CLAD. Such an approach for instituting ECP therapy early based on detection of circulating exosomes with lung SAgs should assist in preventing and or treating LTxRs diagnosed with CLAD prior to irreversible damage to the transplanted lungs.

During this study, the discovery cohort analysis of Col-V had a sensitivity of 85.7% and specificity of 100% at 6 months and 90.48% sensitivity and 100% specificity at 12 months prior to clinical diagnosis of BOS. For lung SAg, Kα1T, there was 61.9% sensitivity and 90% specificity at 6 months and sensitivity of 57% and specificity of 80% at 12 months. For the validation cohorts, levels of exosomes containing Col-V demonstrated sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 80% at 6 months and sensitivity of 60% with specificity of 75% at 12 months prior to clinical diagnosis of BOS. For lung SAg, Kα1T, sensitivity was 60% and specificity 80% at 6 months and 65% sensitivity and 80% specificity at 12 months. These results demonstrate that determination of Col-V or Kα1T in circulating exosomes by western blot followed by semi-quantitation possesses higher positive predictive value with excellent sensitivity and specificity. Further, circulating exosomes with lung SAgs can serve as a non-invasive biomarker in predicting risk for BOS at least 12 months prior to clinical diagnosis.

Previous reports have demonstrated that plasma from heart transplant recipients with cardiac allograft vasculopathy contain Abs to cardiac SAgs (myosin and vimentin).31, 32 In addition, kidney transplant recipients diagnosed with transplant glomerulopathy, a risk factor for developing chronic rejection, also develop Abs to kidney SAgs (fibronectin, Col-IV, and LG3).33–36 Recently we showed that exosomes isolated from heart and kidney transplant recipients contain tissue associated SAgs19 and demonstrated the exosomes’ importance in graft failure using a syngeneic murine heart transplant model. A recent report demonstrated that circulating C4d+ plasma endothelial macrovesicle levels were increased in human kidney transplant recipients with acute antibody mediated rejection.37 This signifies that de novo development of Abs can stimulate exosome and may contribute in rejection. These results suggest that circulating exosomes containing tissue associated SAgs can occur in other solid organ transplants also and exosomes with tissue associated SAgs can serve as a non-invasive biomarker for kidney and heart transplant recipients at risk for developing chronic rejection.

There are some limitations for our study which includes: 1) That all of our analysis for exosomes containing lung SAgs are from samples collected retrospectively from LTxRs. 2) Due to the retrospective nature of our analysis, exact pairing of BOS and stable patients were not carried out. 3) All of our analysis included only BOS patients and further analysis of restrictive allograft syndrome are needed. 4) Since we have performed quantitation of western blot using specific Abs to lung SAgs, this approach may not be easily translatable into a clinical situation. However, availability of image screen analysis using labelled Abs specific to lung SAgs are possible and therefore should be translatable into a clinical laboratory.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate the importance of circulating exosomes in the development of immune responses leading to chronic rejection. Our data, using different sets of plasma samples collected from 2 different LTx centers, demonstrated that circulating exosomes with lung SAgs can be detected 12 months prior to the diagnosis of BOS indicating that circulating exosomes with lung SAgs can be a viable non-invasive biomarker for identifying patients at risk for developing CLAD. Early detection of patients at risk for developing chronic rejection provides an opportunity to develop strategies to prevent or intervene prior to the onset of irreversible damage to the transplanted organ. Further, based on the reports that Abs to tissue associated SAgs can be detected prior to chronic rejection following human renal and cardiac transplantations, we propose that circulating exosomes with tissue associated SAgs has the potential to be a non-invasive biomarker for identifying not only LTxRs at risk for developing CLAD but also other solid organ transplant recipients at risk for developing chronic rejection, a major problem in clinical transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank C. Sontag and B. Glasscock for assistance with manuscript editing and preparation.

Sources of Support: This research was supported by NIH HL056643, R21AI123034, and St. Joseph Foundation (TM).

Abbreviations:

- Abs

antibodies

- AUC

area under curve

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BOS

bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

- CLAD

chronic lung allograft dysfunction

- Col-V

Collagen V

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- Kα1T

K-alpha 1 Tubulin

- LTx

lung transplantation

- LTxRs

lung transplant recipients

- PGD

primary graft dysfunction

- ROC

receiver operating curve

- RVI

respiratory viral infection

- SAgs

self-antigens

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement:

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Estenne M, and Hertz MI. Bronchiolitis obliterans after human lung transplantation. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2003;166 440–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers DC, Yusen RD, Cherikh WS, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fourth Adult Lung And Heart-Lung Transplantation Report-2017; Focus Theme: Allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:1047–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pakhale SS, Hadjiliadis D, Howell DN, et al. Upper lobe fibrosis: a novel manifestation of chronic allograft dysfunction in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:1260–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato M, Waddell TK, Wagnetz U, et al. Restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS): a novel form of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011;30:735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke CM, Theodore J, Dawkins KD, et al. Post-transplant obliterative bronchiolitis and other late lung sequelae in human heart-lung transplantation. Chest 1984;86:824–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper JD, Billingham M, Egan T, et al. A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature and for clinical staging of chronic dysfunction in lung allografts. International Society for Heart and Lung Translantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1993;12:713–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001: an update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant 2002;21 297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer MR, Stoehr C, Whang JL, et al. The diagnosis of obliterative bronchiolitis after heart-lung and lung transplantation: low yield of transbronchial lung biopsy. J Heart and Lung Transplantation 1993;12:675–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hachem RR, Chakinala MM, Yusen RD, et al. The predictive value of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome stage 0-p. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:468–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weigt SS, Wang X, Palchevsky V, Gregson AL, Patel N, DerHovanessian A, Shino MY, Sayah DM, Birjandi S, Lynch JP 3rd, Saggar R, Ardehali A, Ross DJ, Palmer SM, Elashoff D, Belperio JA Gene expression profiling of bronchoalveolar lavage cells preceding a clinical diagnosis of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy VE, Todd JL, and Palmer SM. Bronchoalveolar lavage as a tool to predict, diagnose and understand bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Am J Transplant 2013;13:552–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunasekaran M, Xu Z, Nayak DK, Sharma M, Hachem R, Walia R, Bremner RM, Smith MA, Mohanakumar T Donor-derived exosomes with lung self-antigens in human lung allograft rejection. Am J Transpl 2017;17(2):474–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burlingham WJ, Love RB, Jankowska-Gan E, et al. IL-17-dependent cellular immunity to collagen type V predisposes to obliterative bronchiolitis in human lung transplants. J Clin Invest 2007;117:3498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregson AL, Hoji A, Injean P, Poynter ST, Briones C, Palchevskiy V, Weigt SS, Shino MY, Derhovanessian A, Sayah D, Saggar R, Ross D, Ardehali A, Lynch JP 3rd, Belperio JA Altered exosomal RNA profiles in bronchoalveolar lavage from lung transplants with acute rejection. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2015;192:1490–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verleden GM, Glanville AR, Lease ED, et al. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: Definition, diagnostic criteria, and approaches to treatment-A consensus report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glanville AR, Verleden GM, Todd JL, Benden C, Calabrese F, Gottlieb J, Hachem RR, Levine D, Meloni F, Palmer SM, Roman A, Sato M, Singer LG, Tokman S, Verleden SE, von der Thusen J, Vos R, Snell G Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: Definition and update of restrictive allograft syndrome-A consensus report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. J Heart and Lung Transplantation 2019;38(5):483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher CE, Kapnadak SG, Lease ED, Edelman JD, Limaye AP Interrater agreement in the diagnosis of chronic lung allograft dysfunction after lung transplantation. J Heart and Lung Transplantation 2019;38(3):327–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles 2018;7:1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma M, Ravichandran R, Bansal S, et al. Tissue-associated self-antigens containing exosomes: Role in allograft rejection. Hum Immunol 2018;79:653–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaffiri L, Shah RJ, Stearman RS, et al. Collagen type-V is a danger signal associated with primary graft dysfunction in lung transplantation. Transpl Immunol 2019;56:101224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwata T, Philipovskiy A, Fisher AJ, et al. Anti-type V collagen humoral immunity in lung transplant primary graft dysfunction. J Immunol 2008;181:5738–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo E, Maruyama T, Fernandez F, et al. Molecular mechanisms of chronic rejection following transplantation. Immunol Res 2005;32:179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hachem RR, Tiriveedhi V, Patterson GA, et al. Antibodies to K-alpha 1 tubulin and collagen V are associated with chronic rejection after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2012;12:2164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Z, Nayak D, Yang W, Baskaran G, Ramachandran S, Sarma N, Aloush A, Trulock E, Hachem R, Patterson GA, Mohanakumar T Dysregulated microRNA expression and chronic lung allograft rejection in recipients with antobidies to donor HLA. Am J Transpl 2015;15:1933–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bharat A, Saini D, Steward N, Hachem R, Trulock EP, Patterson GA, Meyers BF, Mohanakumar T Antibodies to self-antigens predispose to primary lung allograft dysfunction and chronic rejection. Annals Thoracic Surgery 2010;90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bharat A, Kuo E, Saini D, et al. Respiratory virus-induced dysregulation of T-regulatory cells leads to chronic rejection. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:1637–44; discussion 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almaghrabi RS, Omrani AS, Memish ZA Cytomegalovirus infection in lung transplant recipients. Expert Rev Respir Med 2017;11:377–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher CE, Mohanakumar T, Limaye AP Respiratory virus infections and chronic lung allograft dysfunction: Assessment of virology determinants. J Heart and Lung Transplantation 2016;35:946–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohanakumar T, Sharma M, Bansal S, et al. A novel mechanism for immune regulation after human lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;157:2096–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunasekaran M, Bansal S, Ravichandran R, et al. Respiratory viral infection in lung transplantation induces exosomes that trigger chronic rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020;39:379–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nath DS, Ilias Basha H, Tiriveedhi V, Alur C, Phelan D, Ewald GA, Moazami N, Mohanakumar T Characterization of immune responses to cardiac self-antigens Myosin and Vimentin in human cardiac allograft recipients with antibody mediated rejection and cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Heart and Lung Transplantation 2010;29:1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahesh B, Leong HS, Nair KS, et al. Autoimmunity to vimentin potentiates graft vasculopathy in murine cardiac allografts. Transplantation 2010;90:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Angaswamy N, Klein C, Tiriveedhi V, et al. Immune responses to collagen-IV and fibronectin in renal transplant recipients with transplant glomerulopathy. Am J Transplant 2014;14:685–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giral M, Foucher Y, Dufay A, et al. Pretransplant sensitization against angiotensin II type 1 receptor is a risk factor for acute rejection and graft loss. Am J Transplant 2013;13:2567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunasekaran M, Vachharajani N, Gaut JP, et al. Development of immune response to tissue-restricted self-antigens in simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplant recipients with acute rejection. Clin Transplant 2017;31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banasik M, Boratynska M, Koscielska-Kasprzak K, et al. Long-term follow-up of non-HLA and anti-HLA antibodies: incidence and importance in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc 2013;45:1462–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tower CM, Reyes M, Nelson K, Leca N, Kieran N, Muczynski K, Jefferson JA, Blosser C, Kukla A, Maurer D, Chandler W, Najafian B Plasma C4d+ Endothelial Microvesicles Increase in Acute Antibody-Mediated Rejection. Transplantation 2017;101:2235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.