Abstract

Background

Nitrogen-based nutrients are the main factors affecting rice growth and development. Root systems play an important role in helping plants to obtain nutrients from the soil. Root morphology and physiology are often closely related to above-ground plant organs performance. Therefore, it is important to understand the regulatory effects of nitrogen (N) on rice root growth to improve nitrogen use efficiency.

Results

In this study, changes in the rice root traits under low N (13.33 ppm), normal N (40 ppm) and high N (120 ppm) conditions were performed through root morphology analysis. These results show that, compared with normal N conditions, root growth is promoted under low N conditions, and inhibited under high N conditions. To understand the molecular mechanism underlying the rice root response to low and high N conditions, comparative proteomics analysis was performed using a tandem mass tag (TMT)-based approach, and differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) were further characterized. Compared with normal N conditions, a total of 291 and 211 DAPs were identified under low and high N conditions, respectively. The abundance of proteins involved in cell differentiation, cell wall modification, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and protein synthesis was differentially altered, which was an important reason for changes in root morphology. Furthermore, although both low and high N can cause nitrogen stress, rice roots revealed obvious differences in adaptation to low and high N.

Conclusions

These results provide insights into global changes in the response of rice roots to nitrogen availability and may facilitate the development of rice cultivars with high nitrogen use efficiency through root-based genetic improvements.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12284-020-00443-y.

Keywords: Nitrogen, Proteomics, Root system morphology, Rice

Background

Rice is one of the most important food crops worldwide, and sustainable development of rice agriculture is an essential part to ensure global food security (Hua et al. 2015). With the acceleration of urbanization, the area of arable land is shrinking, and food production security must be achieved by increasing yields (Sun et al. 2014). In recent years, researchers have steadily increased rice yield through measures such as improving rice varieties, developing advanced cultivation techniques, and increasing production inputs. Among them, increasing the nitrogen input is one of the most effective measures to increase rice production (Godfray et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2013). However, given the significant increase in rice production, excessive and inappropriate nitrogen fertilizer input has also led to a series of problems, such as a decrease in the nitrogen fertilizer utilization rate and an increase in production cost, air pollution, and water pollution cost (Hakeem et al. 2011; Gutiérrez 2012).

Roots not only constitute important organs of rice that absorbs nutrients and moisture but are also the site for assimilation, transformation and synthesis of several substances, such as phytohormones, organic acids, etc. (Wu and Cheng 2014; Meng et al. 2019). Therefore, the morphology and physiology of rice roots are closely related to nitrogen uptake and utilization (Zhang et al. 2009; Lynch 2013). Ju et al. (2015) suggested that N-efficient rice varieties have larger root biomass, deeper root distribution, longer root length, and greater root length density. At the same time, changes in nitrogen availability affect root morphology and physiology (Xu et al. 2012). The morphological and physiological responses of rice roots to changes in N availability have been studied intensively (Marschner 1995; Mi et al. 2010; Ju et al. 2015). Mild nitrogen deficiency can promote root growth, which is conducive to deep root penetration; appropriate nitrogen supply can increase root number, biomass and density; but excessive nitrogen supply can inhibit root growth (Walch-Liu 2006; Francisco et al. 2015). Ju et al. (2015) showed that within a certain range, root biomass and root oxidation activity increased with increasing nitrogen levels. However, the molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying the morphological and physiological acclimation to different nitrogen levels remain largely unknown. Understanding these mechanisms is of great importance for not only the scientific community involved in research on rice biology but also practical rice breeders, as knowledge of rice root responses to nitrogen availability enables the breeding of rice with high nitrogen use efficiency.

In recent years, the development and application of high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) and information processing technologies have advanced. Comparative proteomic analysis plays an important role in understanding the mechanisms by which plants adapt to biotic and abiotic stress (Turek et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2016; Hao et al. 2017; Tian et al. 2018a; Tian et al. 2018b). However, to the best of our knowledge, almost no research has been conducted on the response of rice roots to nitrogen nutrition through integrated morphological and proteomic analysis.

In this study, rice plants were subjected to low, control and high N treatments. The changes in root traits and root proteome profiles were analyzed after 30 days. We found that compared with normal N conditions, root biomass and the total root length increased under low N conditions and decreased under high N conditions. Differences in protein abundance involved in cell division and expansion, lignin synthesis, and nascent protein synthesis could be important factors leading to root morphological changes. The objective of this research is to provide the fundamental information needed to identify strategies employed by rice roots to cope with low and high N stress. This information could be used for research focused on improving nitrogen use efficiency and production of rice.

Results

Architectural Responses of Rice Roots to Nitrogen Availability

To understand the response mechanism of rice roots to low and high nitrogen, the current study conducted an integrated morphological and proteomic analysis. As shown in Table 1, root biomass (Xin et al. 2019b) and total root length significantly decreased under high N conditions as compared to normal N conditions (Table 1, Fig. 1), and increased under low N conditions. The maximum root length significantly increased under low N conditions, but no significant effect was observed under high N conditions. The root diameter was not affected under low N conditions, but it significantly decreased under high N conditions. Low N led to a considerable reduction in root number, but no change under high N. As we previously reported, the nitrogen content increased with increasing nitrogen supply levels (Xin et al. 2019b).

Table 1.

Effects of nitrogen availability on root morphology and nitrogen content

| Treatment | Low N | Normal N | High N | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root biomass (g) | 1.07 ± 0.08a | 0.84 ± 0.03b | 0.66 ± 0.03c | *** |

| Total root length (cm) | 8032.50 ± 396.01a | 6694.83 ± 150.31b | 5423.52 ± 300.58c | *** |

| Maximum root length (cm) | 31.30 ± 0.40a | 27.96 ± 0.62b | 27.41 ± 1.08b | ** |

| Root diameter (mm) | 0.46 ± 0.02a | 0.45 ± 0.03a | 0.36 ± 0.04b | * |

| Root number | 181.67 ± 4.93b | 259.33 ± 7.77a | 245.00 ± 8.72a | *** |

| Root nitrogen content | 2.05 ± 0.08c | 2.44 ± 0.11b | 3.39 ± 0.13a | *** |

Values labeled with different letters in the same row indicate significant differences between the nitrogen treatments. As evaluated with ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, n = 3. The root biomass and root nitrogen content data have been reported in our previous study (Xin et al. 2019b)

Fig. 1.

Effects of N treatments on roots morphology

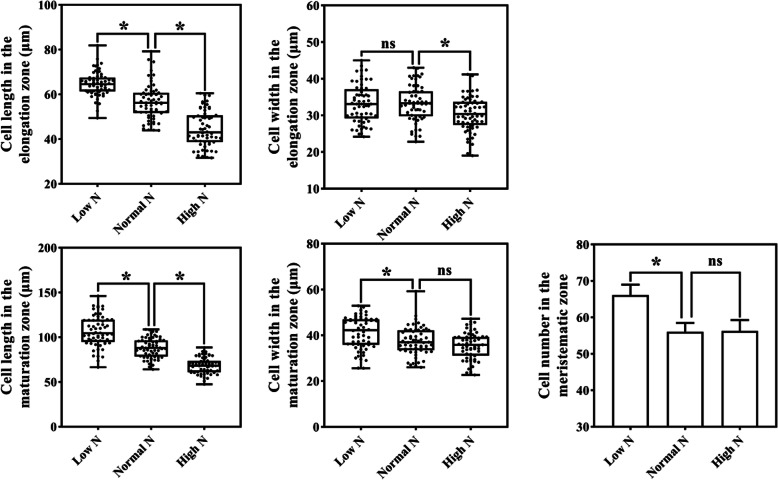

To determine whether the cell division and elongation were affected under different N treatments, the number and size of cells in root tips were examined. As shown in Fig. 2, compared to normal N conditions, the length/width of cell in the elongation zone revealed increased/no significant change under low N condition, while the length/width of cell in the elongation zone revealed decreased/decreased under high N condition. Compared to normal N conditions, the length/width cell in the maturation zone revealed increased/increased under low N condition, while the length/width of cell in the maturation zone revealed decreased/no significant change under high N condition. Compared to normal N conditions, cell number in the meristematic zone increased under low N conditions, but did not change significantly under high N conditions. This result indicates that changes in cell division and cell expansion may contribute to the changed root length of rice under low and high N conditions.

Fig. 2.

Changes of cell size in rice roots in response to low and high N. a cell length in the elongation zone. b cell width in the elongation zone. c cell length in the maturation zone. d cell width in the maturation zone. e cell number in the meristematic zone, 10,000 μm2. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the two N treatments, (as evaluated with ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD, *, p < 0.05, ns, not significant. n = 60 (cell length and width), n = 9 (cell number))

Overview of Root Proteome Profiles in Response to Different N Treatments

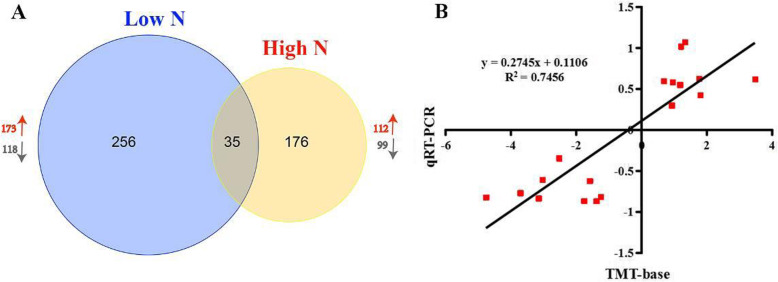

To understand the molecular basis of changes in rice root morphology and function under different N regimes, rice root samples under the three N conditions (low N, normal N, and high N) were characterized with tandem mass tag (TMT)-based proteomics. A total of 6169 rice root proteins were identified under the three N conditions (Fig. S1). Compared to normal N, there were 291 differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) in the roots under low N conditions, 173 of which exhibited increased abundance, while 118 exhibited decreased abundance. Compared to normal N, there were 211 DAPs in the roots under high N conditions, 112 of which exhibited increased abundance, while 99 exhibited decreased abundance. More proteins increased in abundance than decreased in abundance under both low and high N conditions (Fig. 3a). Among them, 35 proteins were identified as DAPs under both low and high N conditions, from which, nine DAPs were selected for qRT-PCR analysis. The proteome profiles were reliable as a high correlation (0.74) was detected between the qRT-PCR and TMT quantification. (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Proteomic analysis of rice roots under low and high N conditions. a the total number of DAPs under low and high N conditions; b a qRT-PCR assay was carried out for 9 randomly selected DAPs. The values are the log2 (Fold charge) (low N/control N or high N/control N) for genes or proteins. The correlation coefficient (R2) is indicated in the figure

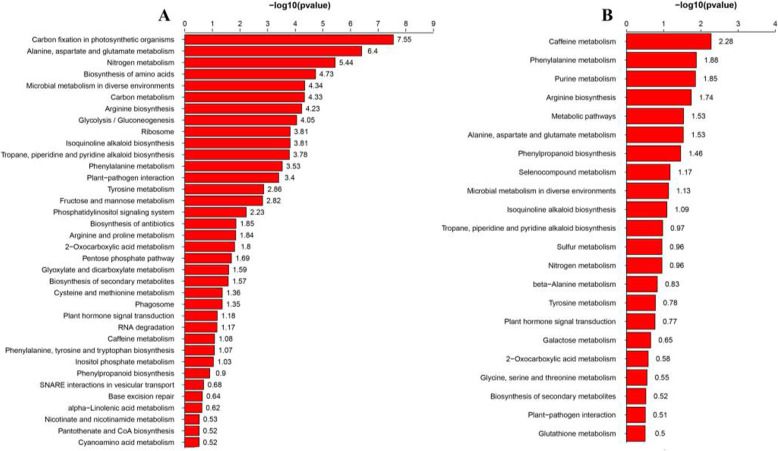

To obtain insights into the main biological functions of DAPs and the metabolic processes involved, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed. All DAPs enrichment analyses showed that carbon metabolism, nitrogen metabolism, amino acid metabolism, stress and defense-related metabolism, and protein synthesis processes were significantly enriched (Fig. 4a). In addition, enrichment analysis of the DAPs in low and high N suggested that the top three enriched pathways were caffeine metabolism, phenylalanine metabolism, and purine metabolism (allantoin metabolism) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

KEGG analysis of DAPs in rice roots under low and high N conditions. a, KEGG analysis of all identified DAPs under low and high N conditions; b, KEGG analysis of DAPs shared by the low and high N conditions. The -log10 values of Fisher’s exact test p values for the significant pathways are shown on the X axis

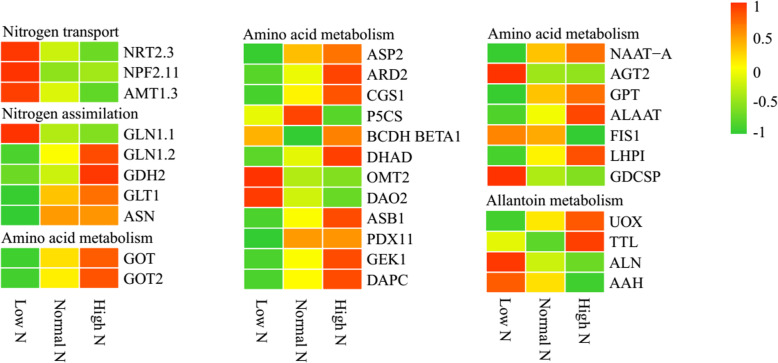

Nitrogen Uptake and Assimilation in Rice Roots

As shown in Fig. 5, compared with normal N conditions, the nitrogen transporter proteins NRT2.3, NPF2.11 and AMT1.3 exhibited increased abundance under low N conditions, while AMT1.3 exhibited decreased abundance under high N conditions. Five nitrogen assimilation-related proteins were identified as DAPs; all except GLN1.1 exhibited decreased abundance under low N conditions. GDH2 exhibited increased abundance under high N conditions. Nineteen amino acid metabolism-related proteins were identified as DAPs, 15 were identified under low nitrogen conditions, all except OMT2, AOC2, AGT2 and GDCSP exhibited decreased abundance. Eight were identified under high N conditions, all except P5CS and AOC2 exhibited increased abundance. Notably, allantoin metabolism-related proteins exhibited opposite changes in protein relative abundance under low and high N conditions.

Fig. 5.

Differential changes in nitrogen metabolism-related proteins in rice roots under low and high N conditions. Proteins were displayed by different colors. Relative levels of abundance are showed by a color gradient from low (green) to high (red). For each heatmap from left to right: Low N, Normal N, High N

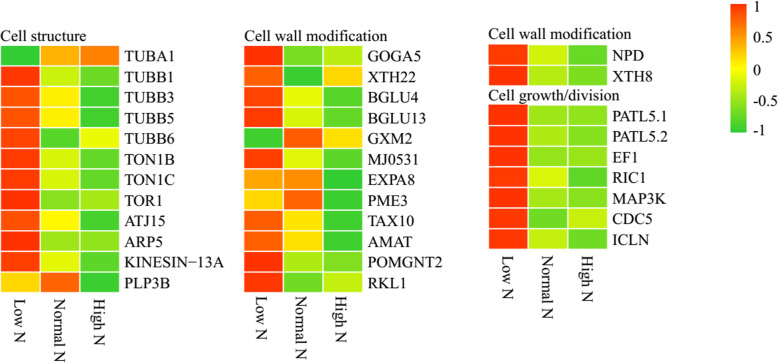

Cell Structure and Growth-Related Proteins

As shown in Fig. 6, compared with normal N conditions, 33 cell structure- and growth-related proteins were identified as DAPs. Among the cell structure-associated proteins, eight were identified as DAPs under low N conditions, and all except TUBA1 exhibited increased abundance. Additionally, six were identified as DAPs under high N conditions, which exhibited decreased abundance. Among the cell wall-related proteins, 11 were identified as DAPs under low N conditions, and all except GXM2 exhibited increased abundance, six were identified as DAPs under high N conditions, which exhibited decreased abundance. Among the cell growth/division-related proteins, seven were identified as DAPs under low N conditions, which exhibited increased abundance.

Fig. 6.

Differential changes in cell structure- and growth-related proteins in rice roots under low and high N conditions. Proteins were displayed by different colors. Relative levels of abundance are showed by a color gradient from low (green) to high (red). For each heatmap from left to right: Low N, Normal N, High N

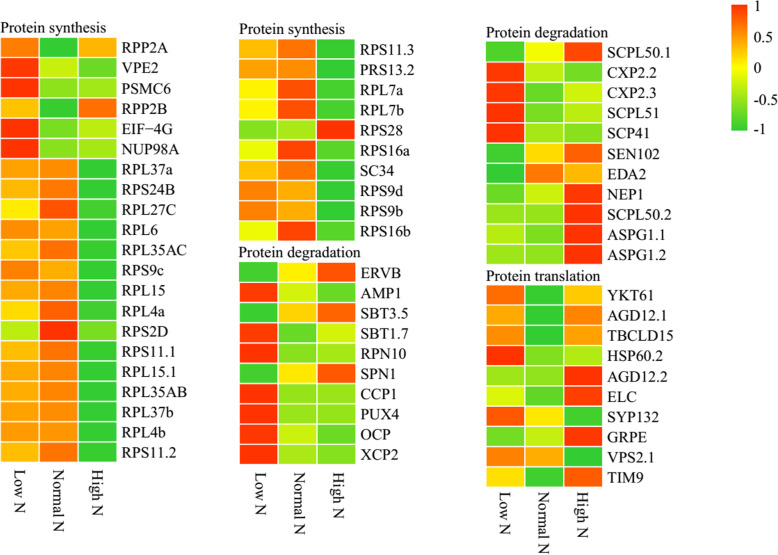

Protein Homeostasis-Related Proteins

As shown in Fig. 7, compared with normal N conditions, 62 protein homeostasis-related proteins were identified as DAPs. Among the protein synthesis-related proteins, six were identified under low N conditions, which exhibited increased abundance, 25 were identified as DAPs under high N conditions, all except RPS28 showed decreased abundance. Among the protein degradation-related proteins, 18 were identified as DAPs under low N conditions, all except ERVB, SBT3.5, SPN1, SCPL50.1, SEN102, EDA2, and NEP1 exhibited increased abundance. Additionally, six were identified as DAPs under high N conditions, all except AMP1 and OCP exhibited increased abundance. Among the protein translation-related proteins, 4 were identified as DAPs under low N conditions, which exhibited increased abundance, and seven were identified as DAPs under high N conditions, all except TBCLD15, SYP132 and VPS2.1 exhibited increased abundance.

Fig. 7.

Differential changes in protein homeostasis-related proteins in rice roots under low and high N conditions. Proteins were displayed by different colors. Relative levels of abundance are showed by a color gradient from low (green) to high (red). For each heatmap from left to right: Low N, Normal N, High N

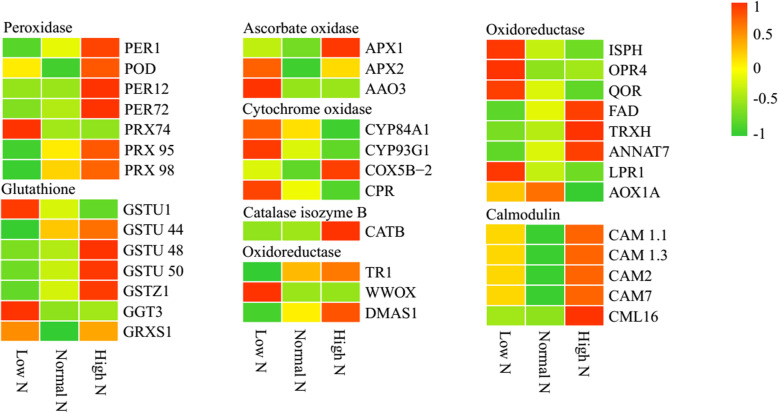

Stress- and Defense-Related Proteins

As shown in Fig. 8, compared with normal N conditions, 39 stress- and defense-related proteins were identified as DAPs. Seven peroxidases were identified, four were identified under low N conditions, and all except PRX74 exhibited decreased abundance. In addition, four were identified under high N conditions, which exhibited increased abundance. Seven glutathione metabolism-related proteins were identified as DAPs, five were identified as DAPs under low N conditions, all except GSTU44 and GSTU50 exhibited increased abundance, three were identified as DAPs under high N conditions, and exhibited increased abundance. Three ascorbate-related proteins were identified as DAPs, the abundance of AAO3 and APX2 increased under low N conditions, and the abundance of APX1 increased under high N conditions. Four cytochrome oxidase-related proteins were identified as DAPs, the abundance of CPR and CYP93A2 increased under low N conditions, while the abundance of COX5B-2 increased and CYP84A1 decreased under high N conditions. The abundance of the catalase isozyme CATB increased under high N conditions. Eleven redox-related proteins were identified as DAPs, nine were identified under low N conditions, all except TR1, DMAS1, FAD and TRXH exhibited increased abundance. Four were identified as DAPs under high N conditions, all expect QOR and AOX1A exhibited increased abundance. Notably, five calmodulin-related proteins exhibited increased abundance under high N conditions.

Fig. 8.

Differential changes in stress- and defense-related proteins in rice roots under low and high N conditions. Proteins were displayed by different colors. Relative levels of abundance are showed by a color gradient from low (green) to high (red). For each heatmap from left to right: Low N, Normal N, High N

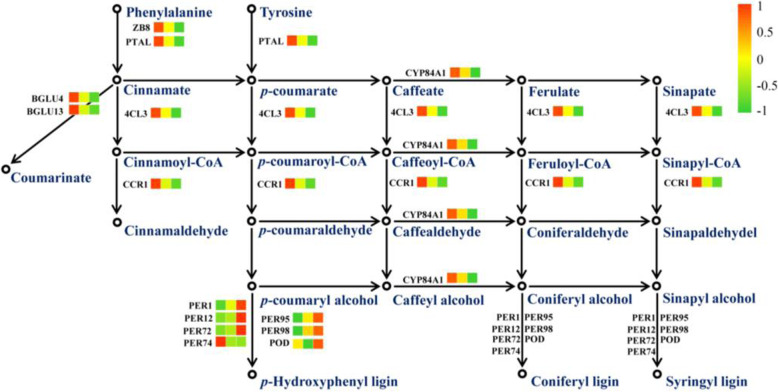

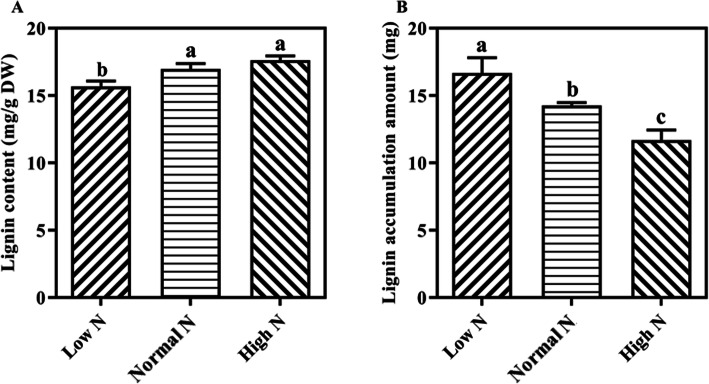

Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis

Phenylalanine metabolism and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis were enriched in both DAPs and shared DAPs (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 9, the abundance of the main enzymes PAL, 4CL3, CCR1 and CYP93A2 involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis increased under low N conditions. The abundance of the main enzymes ZB8, PAL, CCR1 and CYP84A1 involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis decreased under high N conditions. Root lignin content decreased under low N conditions, no significant effect was observed under high N conditions. However, root lignin accumulation amount decreased with increasing nitrogen supply levels (Fig. 10). A total of 7 peroxidases involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis were identified as DAPs under low and high N conditions.

Fig. 9.

DAPs enriched in phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathways under low and high N conditions. Proteins were displayed by different colors. Relative levels of abundance are showed by a color gradient from low (green) to high (red). For each heatmap from left to right: Low N, Normal N, High N

Fig. 10.

Rice root lignin content and accumulation amount response to low and high N. Values labeled with different letters in same row indicate significant difference between the N treatments, (as evaluated with ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD, p < 0.05, n = 3), DW, Dry weight

Discussion

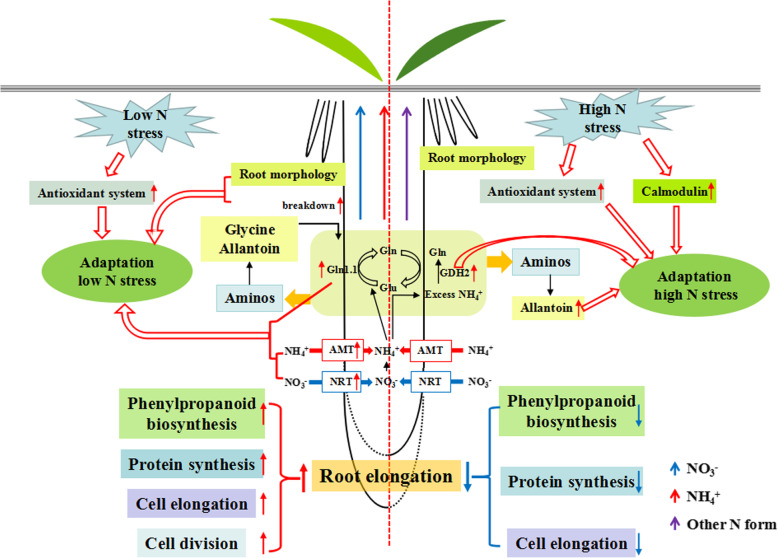

The Distinct and Common Adaptation of Rice Roots to Low Nitrogen and High Nitrogen

Nitrogen nutrients are the main factors affecting rice growth and development. Most previous studies focused on the effects of nitrogen deficiency (Cai et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2015; Curci et al. 2017; Subodh et al. 2018; Qin et al. 2019), while studies on the effects of N excess have been inadequate. However, the current study has shown that there were obvious differences in the morphological characteristics of rice roots under N deficiency and excess conditions, especially, root length was increased under low N conditions, while high N showed the opposite. Previous studies have shown that, when nutrients are insufficient in the environment, plants can improve nutrient acquisition by promoting root distribution in the medium, thereby maintaining survival (Saengwilai et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2019). This result indicated that root morphological characteristics are of great significance to adapt rice to nitrogen stress.

Nitrogen absorption and assimilation are interdependent in plants, and roots play a key role in this process. Inorganic nitrogen is absorbed and transported by specific transport proteins, such as ammonium transporters (AMTs) and nitrate transporters (NRTs) (Hua et al. 2015). In the present study, compared with normal N conditions, abundance of AMT1.3, NRT2.3, and NPF2.11 increased under low N conditions, while abundance of AMT1.3 decreased under high N conditions. Glutamine synthetase (GS) is a key enzyme in nitrogen assimilation (Yang et al. 2016). In rice, the GS protein family has three members, namely, GLN1.1, GLN 1.2, and GLN 1.3, and the function of GLN1.1 cannot be compensated by GLN1.2 and GLN1.3 (Tabuchi et al. 2005). In our study, we observed that compared with normal N conditions, the abundance of GLN1.1 increased under low N conditions. This result indicated that GLN1.1 may have the ability to promote nitrogen assimilation to compensate for nitrogen deficiency. In this study, compared with normal N conditions, the abundance of GDH2 increased under high N conditions, and the high abundance of GDH2 may alleviate ammonium toxicity caused by high N conditions. Interestingly, we observed different responses of allantoin metabolism to low N and high N conditions. The synthesis of allantoin was inhibited and decomposition was promoted by low N, and the opposite was observed under high N conditions. Lescano et al. (2016) showed that osmotic stress can induce the expression of UOX and AS in the allantoin synthesis pathway and inhibit the expression of ALN in the decomposition pathway, which ultimately leads to an increase in allantoin levels. We suggest that NH3+ produced by allantoin decomposition for nitrogen remobilization, may supplement N deficiency. Moreover, the accumulation of allantoin will be able to mobilize the specific response process to adapt to high N stress. Many studies have also demonstrated that plant antioxidant systems are rapidly affected by changes in nutrient conditions (Luo et al. 2015; Curci et al. 2017; Bellegarde et al. 2019). In the current study, a large number of stress-related proteins increased in abundance under low N and high N conditions. Among them, calmodulin exhibited a strong response to high N. Calmodulin is a calcium receptor that is widely found in eukaryotes and is involved in plant growth and the response to various forms of stress (Lee et al. 2005; Chinpongpanich et al. 2012).

In summary, we suggest that under low N conditions, the purpose of rice roots morphology and protein level changes is to enhance N uptake and assimilation to guarantee optimum growth. Under high N conditions, rice root may be adapted to high N stress by increasing the abundance of calmodulin and GDH2, as well as the accumulation of allantoin. Similarly, both low and high N can induce expression of antioxidant-related proteins to adapt to stress.

Potential Regulatory Mechanisms of Root Morphology Response to Low Nitrogen and High Nitrogen

In the present study, the number and size of cells in root tips were affected by low and high N. Proteomics analysis results also shown that, the abundance of proteins involved in cell development was affected by variations in N availability, for example, the expression of microtubule-associated proteins was induced by low N but inhibited by high N. Microtubules are major structural components of eukaryotic cells and play a key role in regulating cell division, cell proliferation and cell morphology (Wasteneys and Yang 2004). Qin et al.’s (2019) research on rapeseed roots under nitrogen deficiency also found similar results. Cell elongation not only increases cytoplasm, but also promotes cell wall components (such as cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, ect.) synthesis to maintain cell wall thickness. In the current study, proteins related to cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin were identified as DAPs under low and high N conditions. Furthermore, compared with normal N conditions, abundance of several cell growth/division- related proteins increased under low N conditions. Therefore, the response of rice root morphology to N availability could be achieved through coordination of these relevant proteins involved in cell structure, cell wall modification and cell division. This coordination could ultimately trigger changes in root morphology with nitrogen availability. Lignin is a major component in the formation of plant skeletons and plays an important role in plant resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia-lyase (PTAL), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) are key enzymes involved in the lignin synthesis pathway. In this study, we observed that the abundance of PTAL, 4CL, and CCR were induced by low N and inhibited by high N. The differences in the abundance of these proteins were in line with the changed lignin accumulation amount under low N and high N conditions. Additionally, this study suggests that the main reason for the low lignin content under low nitrogen conditions is fast root growth. Well known, biomass accumulation is related to protein synthesis. The current study revealed that compared to control N conditions, protein synthesis was promoted by low N conditions and inhibited by high N conditions. Indeed, previous studies have suggested that protein synthesis is one of the main targets for growth control in response to changes in the environment (Wang et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2017). These results suggest that, differentially abundant proteins involved in cell differentiation, lignin synthesis, and nascent protein synthesis in roots are important factors leading to root morphological changes among the three nitrogen treatments.

Conclusion

In this study, we compared root morphological and proteomic profiles across three environmental conditions (N levels). Research results suggest that nitrogen may affect root growth by regulating biological processes such as cell development, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and protein synthesis. In addition, we also found that the adaptation mechanism of rice roots differs greatly under low N and high N conditions. Under low N conditions, rice roots enhance nutrient uptake and utilization by increasing N transport, assimilation and remobilization (glycine, allantoin and protein breakdown) to maintain optimum rice growth and development. Under high N conditions, rice roots determine the abundance of the antioxidant system, calmodulin, allantoin and glutamate dehydrogenase to improve tolerance to high N stress. This study elucidated the molecular mechanism underlying the N-mediated determinants of root growth and development, and provides new insights into improving nitrogen use efficiency in rice (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Schematic model representing the growth and stress in the roots of rice when exposed to low and high N conditions

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials, Mitrogen Treatment and Analysis of Root Characteristics

The experiment was carried out at Shenyang Agricultural University Rice Research Institute, Liaoning Province, China (41°49 N, 123°34 E). Mature rice seeds (cv. ‘shengnong265’ Japonica China) were obtained from the Shenyang Agricultural University Rice Research Institute. Seeds were surface-sterilized with 0.01% HgCl2, allowed to germinate at 28 °C for 2 d, and further cultured in a greenhouse (average temperature of 28/25 °C, photoperiod of 10 h day/14 h night). At three-leaf stage, the seedlings were subjected to 13.33 ppm (low N), 40 ppm (normal N), or 120 ppm (high N) of nitrogen using NH4NO3 as the N source and grown in hydroponics for 30 d during the growing season. The formula for the hydroponic solution was slightly improved as described by Li et al. (2012). All treatments had ten replicates with a completely random design. After 30 d (Tillering stage), the relevant indicators were determined.

Roots were sampled after 30 d of treatments, three biological replicates per treatment. Root number, total root length and root diameter were measured with WinRHIZO Pro 2013e software (Regent Instruments Inc., Quebec, Canada). Maximum root length (the length of the longest whole root from root cap to root tip) was measured with a ruler. Then, the roots were dried in an oven at 80 °C to a constant weight for measuring root biomass. Samples were powdered with a micropulverizer (FZ102, Tianjin, China) to measure root nitrogen content using an elemental analyzer (Elementar Vario MACRO cube, Hanau, Germany). Lignin content was determined with the acetyl bromide method as described previously (Foster et al. 2010). Lignin accumulation amount was calculated by lignin content and root biomass.

After 30 d of nitrogen treatment, cell size and number were investigated in 1-cm root segments starting from the root tip. The root segments (three individual rice plants for each treatment) were fixed using 70% FAA fixative. Sectioning and staining were performed using modified method of Qin et al. (2019). Twenty cells were selected from each root segment in the elongation and maturation zone to determine the length and width using CaseViewer (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary). Three fields of each root segment in the meristematic area were selected and measured cell number, record the number of cells in 10,000 μm2 (Fig. S2).

For experimental variables, one-way of variance (ANOVA) was applied to assess differences among treatments with SPSS 19.0 (Softonic International, Barcelona, Spain) software and drawn using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad, San Diego, USA) software. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by different letters according to Fisher’s LSD. The data presented are the means ± standard errors.

Protein Extraction, Trypsin Digestion and TMT Labeling

Thirty days after nitrogen treatment started, root system samples were collected from 9:00 am to 10:00 am. Three biological replicates per treatment (low N, normal N, and high N) were used for subsequent TMT-based proteomic analysis. Total proteins were extracted using the cold acetone method (Zhang et al. 2018). Samples were ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen and then dissolved in 2 cm3 of lysis buffer (8 M urea, 2% SDS, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland)), followed by sonication on ice for 30 min and centrifugation at 13000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. For each sample, proteins were precipitated with ice-cold acetone at − 20 °C overnight. The precipitates were washed with acetone three times and redissolved in 8 M urea by sonication on ice. Protein quality was examined by SDS-PAGE. The BCA Protein Assay Kit was used to determine the protein concentration in the supernatant. For each condition, one hundred micrograms of protein was transferred into a new tube and adjusted to a final volume of 100 mm3 with 8 M urea. Then, 11 mm3 of 1 M DTT (DL-dithiothreitol) was added, and the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 14000 g for 10 min in a 10 K ultrafiltration tube (Millipore). A total of 120 mm3 of 55 mM iodoacetamide was added to the sample, and the mixture was incubated for 20 min protected from light at room temperature. The precipitates were washed by 1 cm3 pre-chilled 90% acetone aqueous solution for twice and then re-dissolved in 100 mm3 100 mM TEAB. The proteins were then digested with sequence-grade modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) at 37 °C overnight. Then, the digested samples were centrifuged at 13500 g for 12 min, dried under vacuum, and dissolved in 500 mM TEAB. The resultant peptide mixture was labeled with TMT- 10Plex Isobaric Mass Tag Labeling Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. The labeled peptide samples were then pooled and lyophilized in a vacuum concentrator.

HPLC Fractionation and LC-MS/MS Analysis

The peptide mixture was redissolved in buffer A (buffer A: 20 mM ammonium formate in water, pH 10.0, adjusted with ammonium hydroxide) and then fractionated by high-pH separation using an Ultimate 3000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) connected to a reversed-phase column (XBridge C18 column, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm, Waters Corporation, MA, USA). High-pH separation was performed using a linear gradient starting from 5% B to 45% B over 40 min (buffer B: 20 mM ammonium formate in 80% ACN, pH 10.0, adjusted with ammonium hydroxide). The column was re-equilibrated to the initial conditions for 15 min. The column flow rate was maintained at 1 cm3/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 30 °C. Twelve fractions were collected; each fraction was dried in a vacuum concentrator for the next step.

Peptide fractions were resuspended with 30 mm3 of solvent C (C: water with 0.1% formic acid; D: ACN with 0.1% formic acid), separated by nanoLC and analyzed by online electrospray tandem MS. The experiments were performed on an Easy-nLC 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) connected to an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) equipped with an online nanoelectrospray ion source. A 10-mm3 peptide sample was loaded onto the trap column (Thermo Scientific Acclaim PepMap C18, 100 μm × 2 cm) with a flow of 10 mm3/min for 3 min and subsequently separated on an analytical column (Acclaim PepMap C18, 75 μm × 15 cm) with a linear gradient from 2% D to 40% D in 70 min. The column was re-equilibrated to the initial conditions for 10 min. The column flow rate was maintained at 300 μm3/min. An electrospray voltage of 2 kV against the inlet of the mass spectrometer was used. The Fusion mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent acquisition mode to switch automatically between MS and MS/MS acquisition. Full-scan MS spectra (m/z 350–1550) were acquired with a mass resolution of 120 K, followed by sequential high-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) MS/MS scans with a resolution of 30 K. The intense signals in the MS spectra (> 1e4) were subjected to an additional MS/MS analysis. The automatic gain control (AGC) values for MS and MS/MS were set to 4e5 and 8e4, respectively. The maximum ion injection times for MS and MS/MS were 50 and 100 ms, respectively. The isolation window was set to 1.6 Da. In all cases, one microscan was recorded using dynamic exclusion of 30 s.

Database Search

Tandem mass spectra were extracted, charge state deconvoluted and deisotoped by Mascot Distiller version 2.6. Then, the MS data were transformed into MGF files with Proteome Discoverer 1.2 (Thermo, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and analyzed using the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, London, UK; version 2.3.2). The Mascot database was set up for protein identification using the rice (Oryza sativa) protein information from IRGSP-1.0 in ensemble (version 38) database with the following parameters: digestion enzyme, trypsin; 1 missed cleavage allowed. Mascot was searched with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.050 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 20.0 ppm. Carbamidomethyl on cysteine and TMT-10-plex on lysine and the N-terminus were specified in Mascot as fixed modifications. Deamidation of asparagine and glutamine, and oxidation of methionine and acetyl at the N-terminus were specified in Mascot as variable modifications.

Protein Identification, Quantification and Annotation Analysis

Protein identification results were accepted if a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 1.0% was achieved by the Scaffold Local FDR algorithm. Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony. Protein quantification was carried out for those proteins identified in all the samples with ≥2 unique spectra. Protein relative quantification was based on the ratios of reporter ions, which reflect the relative abundance of peptides. The Mascot search results were averaged using medians and quantified. Fold changes > 1.2 and t-test p < 0.05 were used as a threshold to identify the significantly different proteins. Proteins were annotated against the GO (http://www.gene-ontology.org) and KEGG (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) databases for identification of function. Significant GO functions and pathways were examined within DAPs with p value ≤0.05. Heatmap analysis was performed using the OmicShare tools, a free online platform for data analysis (http://www.omicshare.com/tools).

Total RNA Extraction and Verification of the Proteomic Profile

Total RNA extraction was performed with the Eastep Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (Promega), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized with the PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa). Real-time RT-PCR was conducted based on the method described by Xin et al. (2019a). The primers used for RT-PCR analysis are listed in Table S3. Calculation of correlation coefficients and plotting of the proteomic profile and RT-PCR data were performed with Origin 9 (Northampton, MA, USA) software.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Basic protein identification information statistics by TMT analysis.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Schematic diagram of meristem, elongation and maturity zone of the root tip.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Abbreviations list.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Proteomic experiment design.

Additional file 5: Table S3. Sequences of primers used in this study.

Additional file 6: Table S4. DAPs information involved in nitrogen metabolism, cell structure and growth, protein homeostasis, and stress related proteins under low and high N conditions.

Additional file 7: Table S5. Peptide information list for protein identification results.

Additional file 8: Table S6. Protein information list for protein identification results.

Acknowledgments

The National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2018YFD0300306) supported this study.

Abbreviations

- AAH

Allantoate deiminase

- AGD12.1

ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein

- AGD12.2

ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein

- AGT2

Alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase 2

- ALAAT

Alanine aminotransferase 2

- ALN

Allantoinase

- AMAT

Methanol O-anthraniloyltransferase

- AMP1

Glutamate 2

- AMT1.3

Ammonium transporter 1 member 3

- ANNAT7

Annexin D7

- AOX1A

Ubiquinol oxidase

- APX1

L-ascorbate peroxidase 1

- APX2

L-ascorbate peroxidase 2

- ARD2

Acireductone dioxygenase 2

- ARP5

Actin-related protein 5

- ASB1

Anthranilate synthase beta subunit 1

- ASN

Asparagine synthetase 1

- ASP2

Aspartic proteinase Asp1-like

- ASPG1.1

ASPARTIC PROTEASE IN GUARD CELL 1.1

- ASPG1.2

ASPARTIC PROTEASE IN GUARD CELL 1.2

- ATJ15

Chaperone protein dnaJ 15

- BCDH BETA1

2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase subunit beta 1

- BGLU13

Beta-glucosidase 13

- BGLU4

Beta-glucosidase 4

- CAM 1.1

Calmodulin-1.1

- CAM 1.3

Calmodulin-1.3

- CAM2

Calmodulin-2

- CAM7

Calmodulin-7

- CATB

Catalase isozyme B

- CCP1

Cysteine proteinase 1 precursor

- CDC5

Cell division cycle 5

- CGS1

Cystathionine gamma-synthase 1

- CML16

Calcium-binding protein CML16

- COX5B-2

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5b-1

- CPR

NADPH--cytochrome P450 reductase

- CXP2.2

Serine carboxypeptidase II-2

- CXP2.3

Serine carboxypeptidase II-3

- CYP84A1

Cytochrome P450 84A1

- CYP93G1

Cytochrome P450 93G1

- DAO2

Amine oxidase

- DAPC

N-succinyldiaminopimelate aminotransferase

- DAPs

Differentially abundant proteins

- DHAD

Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase

- DMAS1

NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase 1

- EDA2

Serine protease

- EF1

Elongation factor 1-delta 1

- EIF-4G

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G

- ELC

Protein ELC

- ERVB

Ervatamin-B

- EXPA8

Expansin-A8

- FAD

Inactive tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase

- FIS1

1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase

- GDCSP

Glycine dehydrogenase

- GDH2

Glutamate dehydrogenase 2

- GEK1

D-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase

- GGT3

Glutathione gamma-glutamylcysteinyltransferase

- GLN1.1

Glutamine synthetase cytosolic isozyme 1–1

- GLN1.2

Glutamine synthetase cytosolic isozyme 1–2

- GLT1

Glutamate synthase 2

- GOGA5

Golgin-84

- GOT

Aspartate aminotransferase

- GOT2

Aspartate aminotransferase 2

- GPT

L-alanine:2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase

- GRPE

GrpE nucleotide exchange factor domain-containing protein

- GRXS1

Monothiol glutaredoxin-S1

- GSTU 44

Glutathione S-transferase 44

- GSTU 48

Glutathione S-transferase 48

- GSTU 50

Glutathione S-transferase 50

- GSTU1

Glutathione S-transferase 1

- GSTZ1

Glutathione S-transferase 2

- GXM2

Glucuronoxylan 4-O-methyltransferase 1

- High N

High nitrogen

- HSP60.2

Chaperonin CPN60.2

- ICLN

Chloride conductance regulatory

- ISPH

4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase

- KINESIN-13A

Kinesin-13A

- LHPI

Ornithine cyclodeaminase

- Low N

Low nitrogen

- LPR1

Multicopper oxidase

- MAP 3 K

PI-PLC X domain-containing protein

- MJ0531

Universal stress protein MT2085 isoform X2

- N

Nitrogen

- NAAT-A

Nicotianamine aminotransferase A

- NEP1

Aspartic proteinase nepenthesin-1

- Normal N

Normal nitrogen

- NPD

Endoglucanase

- NPF2.11

Protein NRT1/ PTR FAMILY 2.11

- NRT2.3

High-affinity nitrate transporter 2.3

- NUP98A

Nuclear pore complex protein

- OCP

Oryzain alpha chain precursor

- OMT2

O-methyltransferase 2

- OPR4

Putative 12-oxophytodienoate reductase 4

- P5CS

Delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase

- PATL5.1

Patellin-3.1

- PATL5.2

Patellin-3.2

- PDX11

Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthase subunit

- PER1

Peroxidase 1

- PER12

Peroxidase 12

- PER72

Peroxidase 72

- PLP3B

Thioredoxin domain-containing

- PME3

Pectinesterase

- POD

Peroxidase A2

- POMGNT2

Protein O-linked-mannose beta-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 2

- PRS13.2

40S ribosomal protein S13.2

- PRX 95

Peroxidase 95

- PRX 98

Peroxidase 98

- PRX74

Peroxidase 74

- PSMC6

26S protease regulatory subunit 6B homolog

- PUX4

Plant UBX domain-containing protein 4

- QOR

Oxidoreductase

- RIC1

Ras-related protein RIC1

- RKL1

Leucine Rich Repeat family protein

- RPL15

60S ribosomal protein L15

- RPL15.1

60S ribosomal protein L15.1

- RPL27C

60S ribosomal protein L27–3

- RPL35AB

60S ribosomal protein L35a-3

- RPL35AC

60S ribosomal protein L35a-1

- RPL37a

60S ribosomal protein L37a isoform 2

- RPL37b

60S ribosomal protein L37a

- RPL4a

60S ribosomal protein L4a

- RPL4b

60S ribosomal protein L4b

- RPL6

60S ribosomal protein L6–3

- RPL7a

60S ribosomal protein L7a

- RPL7b

60S ribosomal protein L7b

- RPN10

26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 4

- RPP2A

60S acidic ribosomal protein P2A

- RPP2B

60S acidic ribosomal protein p2b

- RPS11.1

40S ribosomal protein S11.1

- RPS11.2

40S ribosomal protein S11.2

- RPS11.3

40S ribosomal protein S11.3

- RPS16a

40S ribosomal protein S16a

- RPS16b

40S ribosomal protein S16b

- RPS24B

40S ribosomal protein S24–1

- RPS28

Os10g0411700, partial

- RPS2D

40S ribosomal protein S2–3

- RPS9b

40S ribosomal protein S9b

- RPS9c

40S ribosomal protein S9c

- RPS9d

40S ribosomal protein S9d

- SBT1.7

Subtilisin-like protease SBT1.7

- SBT3.5

Subtilisin-like protease SBT3.5

- SC34

60S ribosomal protein L10–1

- SCP41

Peptidase S10

- SCPL50.1

Serine carboxypeptidase-like 50

- SCPL50.2

Serine carboxypeptidase 50

- SCPL51

Serine carboxypeptidase-like 51

- SEN102

Zingipain-2-like

- SPN1

Serpin-ZXA

- SYP132

Syntaxin-132

- TAX10

3′-N-debenzoyl-2′-deoxyTaxol N-benzoyltransferase

- TBCLD15

TBC1 domain family member 15

- TIM9

Mitochondrial import inner membrane translocase subunit

- TON1B

Protein TONNEAU 1b

- TON1C

Protein TONNEAU 1c

- TOR1

Microtubule-associated protein SPIRAL2

- TR1

Tropinone reductase

- TRXH

Thioredoxin H1

- TTL

Uric acid degradation bifunctional protein

- TUBA1

Tubulin alpha-1

- TUBB1

Tubulin beta-1

- TUBB3

Tubulin beta-3

- TUBB5

Tubulin beta-5

- TUBB6

Tubulin beta-6

- UOX

Uricase

- VPE2

Vacuolar-processing enzyme

- VPS2.1

Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 2.1

- WWOX

Retinol dehydrogenase 12

- XCP2

Xylem cysteine proteinase 2

- XTH22

Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase 22

- XTH8

Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 8

- YKT61

VAMP-like protein YKT61

Authors’ Contributions

WZ, and WX and JG designed the research plan; XW, JY and XZ performed most of the experiments; CB, DH, SL and XZ recorded most of the experiments data; WX wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2018YFD0300306) supported this study.

Availability of Data and Materials

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD016653. After the data have been published, the access connection in ProteomeXchange will be: http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset? ID = PXD016653.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jiping Gao, Email: jipinggao@syau.edu.cn.

Wenzhong Zhang, Email: zwzhong1@syau.edu.cn.

References

- Bellegarde F, Maghiaoui A, Boucherez J, Krouk G, Lejay L, Bach L, Gojon A, Martin A. The chromatin factor HNI9 and ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 maintain ROS homeostasis under high nitrogen provision. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(1):582–592. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Lu Y, Xie W, Zhu T, Lian X. Transcriptome response to nitrogen starvation in rice. J Biosci. 2012;37:731–747. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinpongpanich A, Limruengroj K, Phean-o-pas S, Limpaseni T, Buaboocha T. Expression analysis of calmodulin and calmodulin-like genes from rice, Oryza sativa L. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):625. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curci PL, Cigliano RA, Zuluaga DL, Janni M, Sanseverino W, Sonnante G. Transcriptomic response of durum wheat to nitrogen starvation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1176. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CE, Martin TM, Pauly M. Comprehensive compositional analysis of plant cell walls (lignocellulosic biomass) part I: lignin. J Vis Exp. 2010;37:e1745. doi: 10.3791/1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco RH, Shane MW, López-Bucio J. Nutritional regulation of root development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4(4):431–443. doi: 10.1002/wdev.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfray HC, Beddington JR, Crute IR, Haddad L, Lawrence D, Muir JF, Pretty J, Robinson S, Thomas SM, Toulmin C. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science. 2010;327:812–818. doi: 10.1126/science.1185383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez RA. Systems biology for enhanced plant nitrogen nutrition. Science. 2012;336:1673–1675. doi: 10.1126/science.1217620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakeem KR, Ahmad A, Iqbal M, Gucel S, Ozturk M. Nitrogen-efficient rice cultivars can reduce nitrate pollution. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2011;18:1184–1193. doi: 10.1007/s11356-010-0434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Guo H, Shi XN, Wang Y, Wan QH, Song YB, Zhang L, Dong M, Shen CJ. Comparative proteomic analyses of two Taxus species (Taxus × media and Taxus mairei) reveals variations in the metabolisms associated with paclitaxel and other metabolites. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58:1878–1890. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua L, Wang DR, Tan LB, Fu YC, Liu FX, Xiao LT, Zhu ZF, Fu Q, Sun XY, Gu P, Cai HW, McCouch SR, Sun CQ. LABA1, a domestication gene associated with long, barbed awns in wild rice. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1875–1888. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju C, Buresh RJ, Wang Z, Zhang H, Liu L, Yang J, Zhang J. Root and shoot traits for rice varieties with higher grain yield and higher nitrogen use efficiency at lower nitrogen rates application. Field Crop Res. 2015;175:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2015.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Polisensky DH, Braam J. Genome-wide identification of touch- and darkness-regulated Arabidopsis genes: a focus on calmodulin-like and XTH genes. New Phytol. 2005;165:429–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescano CI, Martini C, González CA, Desimone M. Allantoin accumulation mediated by allantoinase downregulation and ransport by ureide permease 5 confers salt stress tolerance to Arabidopsis plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;91(4–5):581–595. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yang X, Ren B, Shen Q, Guo S. Why nitrogen use efficiency decreases under high nitrogen supply in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. J Plant Growth Regul. 2012;31:47–52. doi: 10.1007/s00344-011-9218-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang Y, Han W, Tang A, Shen J, Cui Z, Vitousek P, Erisman JW, Coulding K, Christie P, Fangmeier A, Zhang F. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature. 2013;494:459–462. doi: 10.1038/nature11917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Zhou J, Li H, Shi W, Polle A, Lu M, Sun X, Luo ZB. Global poplar root and leaf transcriptomes reveal links between growth and stress responses under nitrogen starvation and excess. Tree Physiol. 2015;35(12):1283–1302. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpv091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP. Steep, cheap and deep: an ideotype to optimize water and N acquisition by maize root systems. Ann Bot. 2013;112:347–357. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. 2. London: Academic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Xiang D, Zhu J, Li Y, Mao C. Molecular mechanisms of root development in Rice. Rice. 2019;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12284-018-0262-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi GH, Chen FJ, Wu QP, Lai NW, Yuan LX, Zhang FS. Ideotype root architecture for efficient nitrogen acquisition by maize in intensive cropping systems. Sci China-Life Sci. 2010;53:1369–1373. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4097-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Walk TC, Han P, Chen L, Zhang S, Li Y, Hu X, Xie L, Yang Y, Liu J, Lu X, Yu C, Tian J, Shaff JE, Kochian LV, Liao X, Liao H. Adaption of roots to nitrogen deficiency revealed by 3D quantification and proteomic analysis. Plant Physiol. 2019;179(1):329–347. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saengwilai P, Tian X, Lynch JP. Low crown root number enhances nitrogen acquisition from low-nitrogen soils in maize. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:581–589. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.232603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subodh S, Amitha SV, Saurabh C, Punit T, Sureshkumar V, Manju R, Pranab M. Transcriptome analysis of two Rice varieties contrasting for nitrogen use efficiency under chronic N starvation reveals differences in chloroplast and starch metabolism-related genes. Genes. 2018;9:206. doi: 10.3390/genes9040206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HY, Qian Q, Wu K, Luo JJ, Wang SS, Zhang CW, Ma YF, Liu Q, Huang XZ, Yuan QB, Han RX, Zhao M, Dong GJ, Guo LB, Zhu XD, Gou ZH, Wang W, Wu YJ, Lin HX, Fu XD. Heterotrimeric G proteins regulate nitrogen-use efficiency in rice. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):652–656. doi: 10.1038/ng.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi M, Sugiyama K, Ishiyama K, Inoue E, Sato T, Takahashi H, Yamaya T. Severe reduction in growth rate and grain filling of rice mutants lacking osgs1;1, a cytosolic glutamine synthetase1;1. Plant J. 2005;42(5):641–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian D, Yang L, Chen Z, Chen Z, Wang F, Zhou Y, Luo Y, Yang L, Chen S. Proteomic analysis of the defense response to Magnaporthe oryzae in rice harboring the blast resistance gene Piz-t. Rice. 2018;11(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12284-018-0240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Shi S, Nasir F, Chang C, Li W, Tran LSP, Tian C. Comparative analysis of the root transcriptomes of cultivated and wild rice varieties in response to Magnaporthe oryzae infection revealed both common and species-specific pathogen responses. Rice. 2018;11(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12284-018-0211-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek I, Wheeler JI, Gehring C, Irving HR, Marondedze C. Quantitative proteome changes in Arabidopsis thaliana suspensioncultured cells in response to plant natriuretic peptides. Data in Brief. 2015;4:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walch-liu P. Nitrogen regulation of root branching. Ann Bot. 2006;97(5):875–881. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcj601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Song K, Sun L, Qin Q, Sun Y, Pan J, Xue Y. Morphological and Transcriptome analysis of wheat seedlings response to low nitrogen stress. Plants. 2019;8:98. doi: 10.3390/plants8040098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XC, Chang LL, Tong Z, Wang DY, Yin Q, Wang D, Jin X, Yang Q, Wang LM, Sun Y, Huang QX, Guo AP, Peng M. Proteomics profiling reveals carbohydrate metabolic enzymes and 14-3-3 proteins play important roles for starch accumulation during cassava root tuberization. Sci Rep-UK. 2016;6:19643. doi: 10.1038/srep19643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Xu XY, Gong QQ, Xie C, Fan W, Yang JL, Lin QS, Zheng SJ. Root proteome of rice studied by iTRAQ provides integrated insight into aluminum stress tolerance mechanisms in plants. J Proteome. 2014;98:189–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasteneys GO, Yang Z. New views on the plant cytoskeleton. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3884–3891. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.900133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WM, Cheng SH. Root genetic research, an opportunity and challenge to rice improvement. Field Crops Res. 2014;165:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2014.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin W, Zhang L, Zhang W, Gao J, Yi J, Zhen X, Du M, Zhao Y, Cheng L. An integrated analysis of the Rice Transcriptome and Metabolome reveals root growth regulation mechanisms in response to nitrogen availability. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(23):5893. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin W, Zhang L, Zhang W, Gao J, Yi J, Zhen X, Li Z, Zhao Y, Peng C, Zhao C. An integrated analysis of the Rice Transcriptome and Metabolome reveals differential regulation of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in response to nitrogen availability. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2349. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Fan X, Miller AJ. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:153–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Yoon J, Choi H, Fan Y, Chen R, An G. Transcriptome analysis of nitrogen -starvation-responsive genes in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:31. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0425-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Nian J, Xie Q, Feng J, Zhang F, Jing H, Zhang J, Dong G, Liang Y, Peng J. Rice Ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase regulates nitrogen–carbon Metabolomes and is genetically differentiated between japonica and indica subspecies. Mol Plant. 2016;9:1520–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Ye J, Jia Y, Zhang L, Song X. iTRAQ-based proteomics analyses of sterile/fertile anthers from a thermo-sensitive cytoplasmic male-sterile wheat with Aegilops kotschyi cytoplasm. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(5):1344. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Xue Y, Wang Z, Yang J, Zhang J. An alternate wetting and moderate soil drying regime improves root and shoot growth in rice. Crop Sci. 2009;49:2246–2260. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.02.0099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Yang Y, Zhang J, Jiang F, Craft E, Thannhauser TW, Kochian LV, Liu J. Quantitative iTRAQ proteomics revealed possible roles for antioxidant proteins in sorghum aluminum tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2017;7:2043. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.02043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Basic protein identification information statistics by TMT analysis.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Schematic diagram of meristem, elongation and maturity zone of the root tip.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Abbreviations list.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Proteomic experiment design.

Additional file 5: Table S3. Sequences of primers used in this study.

Additional file 6: Table S4. DAPs information involved in nitrogen metabolism, cell structure and growth, protein homeostasis, and stress related proteins under low and high N conditions.

Additional file 7: Table S5. Peptide information list for protein identification results.

Additional file 8: Table S6. Protein information list for protein identification results.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD016653. After the data have been published, the access connection in ProteomeXchange will be: http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset? ID = PXD016653.