Abstract

Visual attention measures of receptive vocabulary place minimal task demands on participants and produce a more accurate measure of language comprehension than parent report measures. However, current gaze-based measures employ visual comparisons limited to two simultaneous items. With this limitation, the degree of similarity of the target to the distractor can have a significant impact on the interpretation of task performance. The current study evaluates a novel gaze-based paradigm that includes an eight-item array. This Visual Array Task (VAT) combines the theoretical frameworks of the Intermodal Preferential Looking Paradigm and looking-while-listening methods of language comprehension measurement but using a larger array of simultaneously presented items. The use of a larger array of items and the inclusion of a superordinate category contrast may provide a more sensitive measure of receptive vocabulary as well as an understanding of the extent to which early word comprehension reflects knowledge of broader categories. Results indicated that the tested VAT was a sensitive measure of both object label and category knowledge. This paradigm provides researchers with a flexible and efficient task to measure language comprehension and category knowledge while reducing behavioral demands placed on participants.

Keywords: Visual Array Task (VAT), eye-tracking, language development, receptive vocabulary, categorization, infancy

1. Introduction

The development of experimental measures of receptive language such as the Intermodal Preferential Looking Paradigm (IPLP; Golinkoff et al., 1987) and the looking-while-listening procedure (LWL; Fernald et al., 1998) have provided researchers with objective measures of language comprehension. These tasks require a less demanding behavioral response from participants compared to commonly utilized standardized developmental assessments such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1993) and the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen, 1995). It has been suggested that these experimental methods may also provide a more accurate measure of receptive vocabulary than parent report measures (Houston-Price et al., 2007). Despite reducing the impact of confounds associated with interaction-based assessments and parent-report questionnaires, these attention-based measures of receptive language still have limitations. Chiefly, both the IPLP and the LWL procedures, with few exceptions (Brady et al., 2014), rely on a forced-choice paradigm. When a target item is paired with only a single distractor the interpretation of task performance is heavily reliant upon the chosen stimuli. If care is not taken to select appropriate stimulus sets, this may lead to an overestimation of participant ability. However, current eye tracking technologies allow for the measurement of language comprehension using multiple item arrays, thus allowing for a more robust task that better approximates the naturalistic complexity of the real world. Use of a larger array also allows for the possibility of studying additional related constructs such as the development of category knowledge and its relationship to word knowledge. Therefore, the present study evaluated the use of an eight-item stimulus array, referred to as the Visual Array Task (VAT), to assess the development of object label and category understanding within the context of a single assessment.

1.1. Attention-Based Measures of Language Comprehension

Many measures of early language development rely on parental report and, hence, are susceptible to differences in parents’ ability to infer language comprehension from their child’s behavior (Law & Roy, 2008; Tomasello & Mervis, 1994). To reduce such bias and variability, researchers have turned to experimenter-administered measures such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and the MSEL. However, these assessments require infants and toddlers to interact with an often-unfamiliar examiner and provide either verbal or gestural responses (such as pointing to an image in a test booklet) that may lead to a systematic underestimation of language comprehension abilities.

Two less behaviorally demanding measures of receptive language are the Intermodal Preferential Looking Paradigm (IPLP; Golinkoff et al., 1987) and the looking-while-listening methodology (LWL; Fernald et al., 1998; Fernald et al., 2008). These gaze-based methods present children with two images and a single verbal label. For example, a child may be presented with an image of an apple and an orange while hearing the word “apple” spoken. Linguistic knowledge is then inferred by observing preferential fixation of the labeled stimulus and/or by coding moment-by-moment changes in gaze behaviors related to the onset of the linguistic stimulus. In our previous scenario, experimenters could measure overall duration of looking to the apple and orange as well as where the child was looking during relevant points in the linguistic signal, such as the phonemic onset “æ”, which would quickly distinguish the two words from one another. Thus, these attention-based methodologies provide a behavioral measure of receptive language without relying on parent report, examiner interaction and/or more demanding verbal or gestural responses from the participant.

1.2. The Developmental Intersection of Language and Category Knowledge

While there is debate as to the direction of the relationship between categorization and language development, Waxman and Markow (1995) offered the first evidence supporting a link between the two in infancy. Examining the noun-category linkage in early lexical development Waxman and Markow found that for 12- to 13-month-old infants object category labels learned during a familiarization phase would generalize to new exemplars during a testing phase. Findings reported since this seminal study support the notion that infants are able to generalize object labels from an exemplar to similar objects belonging to the same category based on perceptual, functional, and conceptual properties (for a review, see Ferguson & Waxman, 2017). For example, when a dog is labeled for infants, infants know that the label dog does not only apply to that one specific dog, say a family pet, but also to other dogs they may encounter. Of course, at some level, this must be a bidirectional process. While categories can help infants learn object names, labeling objects can also aid in the recognition of commonalities between object category members. For example, naming basic level objects, such as a dog or a cat, with the superordinate label animal promotes attention to the features those two objects have in common- like fur and independent motion, but not barking.

1.3. The Sequential Touching Paradigm

Various methods have been developed to study category knowledge in infants and young toddlers (Mareschal & Quinn, 2001). One task used with toddlers is the sequential touching procedure (Mandler et al., 1987; Ricciuti, 1965; Starkey, 1981). During this procedure, infants are presented with a group of objects that form two or more categories (e.g. four animals and four vehicles). Children are encouraged to manipulate the objects and then are given several minutes to play with the objects in any way they choose. These interactions are recorded, and the number and sequence of item touches are scored after the play session. Interestingly, children naturally begin to touch the objects in sequences that indicate their awareness of category relationships. When children make more sequential touches to objects of the same category than would be expected by chance, category knowledge is inferred. Various types of category contrasts can be used depending on the specific aims of the study. A common question examined by this paradigm is whether young children have knowledge of superordinate (global; Mandler et al., 1987), basic, and subordinate classes of objects. Findings indicate that between 18 and 30 months of age, infants spontaneously categorize only at the superordinate level. At 30 months of age, toddlers begin to spontaneously categorize at both the basic and superordinate category level (Mandler et al., 1988; Mandler et al., 1991).

1.4. The Present Study

A significant concern of current gaze-based methodologies is that they only require participants to distinguish a verbally labeled target from a single alternative “distractor” item. This approach results in the evaluation of language comprehension as though it is an all-or-nothing construct, limiting experimenter ability to assess the nuanced relationship between lexical units and individual referents. When there are only two items, the similarity of the target to the distractor can have a significant impact on the interpretation of task performance (Arias-Trejo & Plunkett, 2010). For example, imagine a scenario in which a child is presented with two images and told to “look at the dog”. If that child is presented with a dog vs. cow, they may not look preferentially to the dog because of the perceptual similarity of the two items. Here, a lack of looking would be interpreted as the child not yet having acquired the object name for dog. In contrast, the same child might look preferentially to the dog when it is paired with a car or even another animal that is perceptually very different (e.g. a turtle). In this case, the same child’s behavior would be (likely incorrectly) interpreted as knowledge of the specific object label for dog. Thus, results are highly dependent on the nature of any given comparison and do not fully capture the complexity of language comprehension.

Additionally, two-item forced-choice paradigms are highly susceptible to misinterpretation of gaze-behaviors due to the use of alternative problem-solving strategies, not indicative of specific vocabulary knowledge. For example, according to the mutual exclusivity (Markman & Wachtel, 1988) and novel name-nameless category (N3C; Golinkoff et al., 1994) principles, children may preferentially fixate the target object, not because they know the label of the target, but rather, because they know the label of the distractor. When presented with two objects, one familiar and one novel, children will attribute a novel object label to the unknown category. This ability to fast-map is often linked to the vocabulary growth spurt that occurs around 18 months of age (Mervis & Bertrand, 1994).

The present study addresses these limitations by evaluating a novel gaze-based paradigm using an eight-item stimulus array, the Visual Array Task (VAT). The VAT combines the theoretical frameworks of the IPLP and LWL methodology of receptive language with the sequential touching paradigm of object categorization. The expansion of the task to include eight items allows for not only a more precise and gradated measurement of language comprehension, eliminating the concerns of forced choice paradigms, but also the opportunity to measure object label knowledge within the context of multiple category relationships. Therefore, the stimuli for this task included a superordinate category contrast with four objects belonging to one superordinate category (e.g. animals) and four objects belonging to another superordinate category (e.g. items of clothing). The use of a larger array of items and the inclusion of a superordinate category contrast could provide a more sensitive measure of receptive vocabulary as well as a better understanding of the extent to which early word comprehension reflects knowledge of broader categories. It also allows for the examination of the relationship between receptive vocabulary and object category knowledge as measured by the same behavioral task.

Based on findings from the IPLP and LWL methodology, it was predicted that toddlers would understand the object label and demonstrate a preference for fixating the target object compared to other objects belonging to either the target-category or other-category. Similarly, given the expected growth in receptive vocabulary from 17 to 25 months of age, it was predicted that toddlers would fixate the target object longer at 25 months of age compared to 17 months of age. Both the IPLP and the LWL methodology have demonstrated a degree of convergent validity with standardized measures of receptive language (Golinkoff et al., 2013; Law & Roy, 2008); thus, it was also predicted that the VAT would as well. This is the first task to probe category knowledge in such a way; therefore, corresponding analyses of fixation duration and frequency were considered exploratory and no specific predictions related to indictors of category knowledge were made. The use of an eight-item array also allowed for analyses of how participants sequentially looked at the stimuli thus allowing for comparisons to sequential touching tasks used to study category knowledge.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Forty-one toddlers from English-speaking households completed the VAT at 17 and/or 25 months of age, resulting in the collection of data from a total of 54 unique task administrations (see Table 1). A subset of thirteen toddlers, hereafter referred to as the longitudinal cohort, completed the VAT at both 17 and 25 months of age. Participants were recruited by the Autism Center of Excellence (ACE) at the University of Pittsburgh and drawn from a larger study conducted by the Center for Infant and Toddler Development (ITDC). Exclusionary criteria included a reported birth weight less than 2500 grams, problems with pregnancy, labor or delivery, traumatic brain injury, prenatal illicit drug or alcohol use, and/or birth defects. Informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all study participants prior to participation and all study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh and conform to Common Rule standards.

Table 1.

Demographic information for the cross-sectional samples and the longitudinal cohort.

| 17 Months |

25 Months |

LC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 17) | (N = 37) | (N = 13) | ||||

| Age 17 months (M, SD) | 17 | 16.94, 1.18 | - | - | 13 | 17.05, 1.34 |

| Age 25 months (M, SD) | - | - | 37 | 24.74, 0.73 | 13 | 24.82, 0.61 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (%) | 12 | (71%) | 22 | (59%) | 10 | (77%) |

| Female (%) | 5 | (29%) | 15 | (41%) | 3 | (23%) |

| Racial or Ethnic Minority (%) | 1 | (6%) | 2 | (5%) | 1 | (8%) |

| Maternal Education | ||||||

| High School (%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Some College or College Degree (%) | 6 | (50%) | 11 | (46%) | 4 | (40%) |

| Graduate of Professional School (%) | 6 | (50%) | 13 | (54%) | 6 | (60%) |

| Paternal Education | ||||||

| High School (%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Some College or College Degree (%) | 5 | (31%) | 21 | (58%) | 5 | (38%) |

| Graduate of Professional School (%) | 11 | (69%) | 15 | (42%) | 8 | (62%) |

Note. LC = Longitudinal Cohort

2.2. Stimuli

Stimuli depicted an array of eight prototypical color illustrations of common objects, each 7.7 x 7.7 degrees of visual angle (see Figure 1). Importantly, all objects were chosen to represent vocabulary words that 17- and 25-month-old toddlers tend to be familiar with (as determined by normative scores of the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (MB-CDI; Fenson, 2002) and MSEL). Objects presented represented six superordinate categories familiar to children of this age range: vehicles, clothing, animals, food, furniture, and utensils (Mandler et al., 1991; Ross, 1980; see Table 2). Each test-trial stimulus included two different superordinate categories. That is, four objects from each array belonged to one superordinate category (e.g. vehicles) while the remaining four items belonged to another superordinate category (e.g. animals). The locations of objects on the screen were randomized using a 5 (width) x 4 (height) grid system.

Figure 1.

Example of visual stimulus projected on screen.

Table 2.

Objects belonging to each superordinate category.

| Superordinate Category | Object Category Members | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicles | Train | Airplane | Car | Truck |

| Clothing | Hat | Pants | Shoe | Shirt |

| Animals | Cat | Dog | Horse | Bird |

| Food | Bread | Banana | Cookie | Apple |

| Furniture | Door | Table | Bed | Chair |

| Utensils | Plate | Cup | Spoon | Bottle |

For each trial, toddlers heard an audio recording of a female voice naming one of the eight objects (the “target”) on the screen using infant-directed speech. Initial labeling of the target word was time-locked to the appearance of the visual stimulus and the audio recording lasted for the full 10 second during which the image was projected on the screen. Once the array was projected onto the screen, the voice began “(Target, e.g. “dog”). Look at the (target). Where is the (target)? (Target). See the (target)?”. Phrasing was chosen such that the toddlers heard the target name said both as an isolated word and embedded within a sentence, thus maximizing the likelihood of their spontaneously looking at the labeled object. While the phrasing remained the same throughout the testing session, the target object changed with each trial. For a trial in which the target item was the image of a dog, participants heard “Dog. Look at the dog. Where is the dog? Dog. See the dog?”

2.3. Apparatus

Eye tracking took place in a dark, quiet room that resembled a small movie theater. Each participant was seated in a highchair approximately 152 cm from a large projection screen (69 x 91 cm) with their guardian seated next to them. Guardians were instructed not to point to or talk about the images projected onto the screen but were encouraged to comfort the toddlers if necessary. Eye movement data was recorded by a standalone Tobii X120 eye tracker positioned on a table in front of the participant, approximately 81 cm from the screen. Using Tobii Studio software (Version 2.0.6), the stimuli were rear projected on the screen and the participant’s eye movements were recorded at a sampling rate of 60 Hz, accuracy of 0.5 degrees of visual angle, spatial resolution of 0.2 degrees, and drift of 0.3 degrees. Raw eye movement data was then converted into fixations using the Tobii fixation filter (Olsson, 2007).

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Visual Array Task (VAT)

Once the toddler and guardian were seated comfortably, a cartoon played to orient the child toward the screen and maintain his or her attention. When the toddler was quiet and attending to the screen, the cartoon was turned off and a calibration period began. During calibration, toddlers were visually prompted by a moving target to orient their gaze to a total of five predetermined locations on the screen: the center of the screen and each of the four corners. These targets were small, brightly colored objects that simultaneously produced a slight oscillation and corresponding sound. Once the experimenter determined the toddler was attending to the current location, they manually advanced the target to the next location. If the Tobii eye tracker detected both the right and left eye of the toddler at all five target locations, the calibration was considered successful. This process was repeated until a successful calibration was obtained.

Following a successful calibration, toddlers viewed 12 stimulus presentation trials that lasted 10 seconds each. In between each trial, a short cartoon was played to reorient the child’s gaze to the center of the screen. If the participant became upset or distracted during the task, stimulus presentation was halted until the child was calm and attending to the screen again. In total, each toddler saw 12 different eight-object arrays and heard 12 different target words. The presentation of all possible target objects (24) and six superordinate category contrast combinations (out of a possible 15) was counterbalanced across participants. This resulted in six distinct stimulus sets (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

System used to counterbalance target word presentation and category contrasts across the six stimulus sets.

2.4.2. Mullen Scales of Early Learning

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen, 1995) were administered for both the 17- and 25-month age groups. The MSEL is a standardized, observation-based assessment designed to measure four domains of cognitive development (visual reception, fine motor, receptive language, and expressive language) in children from birth to 68 months of age. MSEL administration took place in a small quiet room. Each session was conducted by a trained member of the research team and video recorded to allow for secondary score verification and clinical review. In rare cases where children became fatigued or upset, the assessment was carried out over two visits to the laboratory. The score from the receptive language scale was considered independently as a standardized measure of language comprehension.

2.5. Data Reduction

2.5.1. Areas of Interest (AOIs)

The manner in which toddlers distributed attention to the stimulus array was determined by creating AOIs that included a 190 x 190 pixel square region (approximate size of each object) surrounding each of the eight objects in the array, using Tobii Studio software. Fixations to these AOIs were then classified into three types. Fixations to the object that was named (e.g., “dog”) were defined as target fixations (1 object per trial). Fixations to the 3 objects belonging to the same superordinate category as the target (e.g, cat, horse, bird) were defined as target-category fixations (3 objects per trial). Fixations to the objects that did not belong to the superordinate category as the target (e.g., hat, pant, shoe, shirt) were defined as other-category fixations (4 objects per trial).

2.5.2. Measures of Visual Attention Distribution

To determine how toddlers distributed their attention among the objects when looking to the screen, proportional fixation durations were computed by dividing the total amount of time infants spent looking within each AOI by the total duration of time participants spent looking to any of the eight AOIs. These proportions were then used to create the following three duration-based variables:

Average Target Fixation: To determine the average proportion of time toddlers spent looking to a target object the proportion of time spent fixating the target object was averaged across the 12 trials.

Average Target-Category Fixation: To determine the average proportion of time that toddlers spent looking to one of the three target-category objects the proportion of time spent fixating the three target-category objects was summed and divided by three for each trial and then averaged across the 12 trials.

Average Other-Category Fixation: To determine the average proportion of time that toddlers spent looking to one of the four other-category objects the proportion of time spent fixating the four other-category objects was summed and divided by four for each trial and then averaged across the 12 trials.

2.5.3. Measures of Systematic Scanning

In traditional tasks of sequential touching and object manipulation contact of an object by hand or with another object is considered a touch (Mandler et al., 1987; Ricciuti, 1965; Starkey, 1981). A successive touch of the same object does not count toward the run length (e.g. picking up an object, placing it down, and then picking up the same object up again). This behavior would be considered analogous to making two or more sequential fixations within the same AOI. Therefore, each visit to one of the eight object AOIs was considered a “touch”. Using a video playback of the eye tracking session, trained coders manually scored the number and sequence of visits between the eight objects. Each time a toddler’s gaze entered and exited an AOI was scored as a visit; therefore, a single visit may contain multiple fixations.

The visit sequences were then used to create two measures of systematic scanning. The first measure was the number of runs toddlers made throughout the testing session. A run constituted two or more sequential visits to objects belonging to a single superordinate category. The second measure was run length of successive looks to the four members of each category. It was used as a proxy for whether or not toddlers scanned the objects systematically (reflecting an impact of category information) or randomly.

- Number of Runs (NRuns):

- NRuns Target Category: The number of runs made between objects belonging to the superordinate category of the target object- summed across all 12 trials.

- NRuns Other-Category: The number of runs made between objects belonging to the superordinate category unrelated to the target object- summed across all 12 trials.

- Mean Run Length (MRL):

- MRL Target Category: The length of all runs within the target category divided by the total number of runs- summed across all 12 trials

- MRL Other-Category: The length of all runs within the other-category divided by the total number of runs- summed across all 12 trials

3. Results

The current study includes a mixture of cross-sectional and longitudinal data. To allow for the greatest power to detect group differences at each age, cross-sectional analyses included data from participants in the longitudinal cohort. Means and standard deviations for the primary variables of interest may be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Eye tracking derived variables and standardized assessment measure scores for the cross-sectional samples and the longitudinal cohort.

| Cross-Sectional

Samples |

Longitudinal Cohort |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 Months |

25 Months |

17 Months |

25 Months |

|||||||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |

| Average Proportion of Fixation Duration | ||||||||||||

| Target | 17 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 37 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 13 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 13 | 0.27 | 0.08 |

| Target-Category | 17 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 37 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 13 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 13 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| Other-Category | 17 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 37 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 13 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 13 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Number of Runs | ||||||||||||

| Target-Category | 17 | 13.82 | 3.50 | 37 | 19.51 | 6.06 | 13 | 14.00 | 4.00 | 13 | 20.54 | 6.86 |

| Other-Category | 17 | 12.06 | 4.34 | 37 | 13.62 | 4.09 | 13 | 13.00 | 4.34 | 13 | 14.15 | 4.81 |

| Mean Run Length | ||||||||||||

| Target-Category | 17 | 3.48 | 0.72 | 37 | 3.63 | 0.71 | 13 | 3.58 | 0.75 | 13 | 3.37 | 0.50 |

| Other-Category | 17 | 3.54 | 0.83 | 37 | 2.80 | 0.45 | 13 | 3.70 | 0.87 | 13 | 2.84 | 0.36 |

| NRuns Ratio | 17 | 1.27 | 0.50 | 37 | 1.46 | 0.43 | 13 | 1.17 | 0.45 | 13 | 1.48 | 0.43 |

| MRL Ratio | 17 | 1.03 | 0.28 | 37 | 1.31 | 0.27 | 13 | 1.01 | 0.29 | 13 | 1.20 | 0.22 |

| MSEL- RL | ||||||||||||

| Raw Score | 16 | 17.56 | 2.80 | 36 | 27.25 | 2.57 | 12 | 17.92 | 2.88 | 13 | 27.31 | 2.66 |

| T-Score | 16 | 47.69 | 10.95 | 36 | 59.53 | 7.73 | 12 | 49.00 | 11.39 | 13 | 58.77 | 7.67 |

Note: NRuns Ratio = number of runs ratio; MRL ratio = mean run length ratio; MSEL-RL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning, Receptive Language subscale.

3.1. Visual Attention Distribution

3.1.1. Do toddlers preferentially look to the target object?

Of primary concern was whether toddlers would preferentially fixate a named target object within a larger eight-item array. To determine if toddlers spent a greater amount of time looking to the target object compared to a non-target object from either the target-category or other-category, one-way repeated measures ANOVAs comparing average fixation duration of the three object types were computed for each of the cross-sectional samples. Post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni correction were used to probe any significant main effects. Results indicated that at 17 months of age there was a significant main effect of object type (F(2,32)=12.53, p<.001, ηp2=.56) such that toddlers spent, on average, a greater proportion of time looking to the target object than an object from either the target-category (p=.02) or the other-category (p=.001). However, no preference was observed between looking to objects in the target-category or other-category (p=.35). At 25 months of age, a main effect of object type (F(2,72)=104.81, p<.001, ηp2=.75) indicated an ordinal pattern of preferential looking such that toddlers looked more to the target object compared to target-category objects (p<.001), and more to target-category objects than other-category objects (p<.001).

3.1.2. Does performance on the VAT correlate with a standardized measure of receptive language?

To assess convergent validity between the VAT and the MSEL receptive language subscale correlation matrices including (1) Average Target Fixation, (2) Average Other-Category Fixation, and (3) the Receptive Language t-score derived from the MSEL were computed separately for each cross-sectional age group. Results of the Pearson’s correlations indicated that there were no significant associations between the variables derived from the VAT and MSEL receptive language subscale scores at 17 months of age (see Table 4). Similarly, results of the Pearson’s correlations at 25 months of age indicated that there was not a significant association between Average Target Fixation and the Receptive Language subscale of the MSEL (see Table 4). However, there were a number of significant negative associations between Average Other-Category Fixation and the other measures observed at 25 months of age. First, there was a significant negative association between Average Target Fixation and Average Other-Category Fixation (r(35) = -0.82, p < .001). This finding supports the observed reciprocal relationship wherein as toddlers look more to the target object they reduce looking to the other-category objects. Second, a moderate negative association was observed between Average Other-Category Fixation and the Receptive Language t-score (r(35) = -0.45, p =.006). This indicates that increased looking to the other-category objects was associated with a lower receptive language subscale score on the MSEL.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix examining relationships between visual attention distribution measures of the VAT and a standardized measure of receptive language for the 17- and 25-month-old cross-sectional samples.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Average Target Fixation | - | −.82** | .30 |

| (2) Average Other-Category Fixation | −.34 | - | −.45** |

| (3) MSEL Receptive Language T-Score | .30 | −.20 | - |

correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed)

Note: Pearson’s correlations for the 17-month-old group are displayed on the bottom of the chart and Pearson’s correlations for the 25-month-old group are displayed on the top of the chart; MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning.

3.2. Systematic Scanning

3.2.1. Do toddlers demonstrate sequential looking during the VAT?

Sequential touching during object manipulation tasks is a natural behavior in which children engage. When presented with an array of objects belonging to two or more categories children begin to touch objects in a sequence that reflects understanding of category relations (Rosch, 1978). It is unknown whether a similar tendency toward sequential looking within categories will emerge when children are presented with a visual array of objects. Collapsing across age, toddlers made on average 18 runs within the target category (MRL target = 3.58) and 13 runs within the other-category (MRL other-category = 3.03) throughout the 12 trials of the VAT. This suggests that toddlers did engage in sequential looking when presented with a visual object array.

3.2.2. Do sequential looking behaviors indicate underlying category knowledge?

In order to test the impact that category membership may have had on scan patterns two ratio variables were created. The first is the number of runs ratio (NRuns ratio) calculated as the number of runs made within the target category divided by the number of runs made within the other category. The second is the mean run length ratio (MRL ratio) calculated as the average run length made within the target category (MRL Target Category) divided by the average run length made within the other category (MRL Other Category). An NRuns ratio value greater than one indicates more frequent sequential looking between items within the target category compared to items of the non-target category; that is, a preference for making more frequent runs between items belonging to the superordinate category of the target. A MRL ratio value greater than one indicates longer sequential looking between items of the target category compared to items of the non-target superordinate category; that is, a preference for making longer sequential runs between items belonging to the superordinate category of the target. To determine if toddlers demonstrated a preference for sequential looking within the target category compared to the other category, one-sample t-tests comparing the NRuns ratio and MRL ratio to the no difference value of 1 were calculated for each cross-sectional age group. Results indicated a preference for making runs within the target category (NRuns ratio; t(16) = 2.22, p = .04) but no difference in the length of runs between the target and other category (MRL ratio; t(16) = 0.42, p = .68) for the 17-month-old group. The 25-month-old group demonstrated more frequent (t(36) = 6.61, p < .001) and longer runs within the target category (t(36) = 7.06, p < .001) compared to the other category.

3.2.3. Do measures of receptive vocabulary correlate with measures of category knowledge?

To assess the relationship between measures of receptive vocabulary and object category knowledge during a single testing session, correlation matrixes were computed separately for the cross-sectional sample at 17 and 25 months of age. The eye tracking variables included in the matrix were: (1) Average Target Fixation, (2) Average Other-Category Fixation, (3) NRuns ratio, and (4) MRL ratio (see Table 5). Pearson’s correlations did not identify any significant associations between the measure of receptive vocabulary (Average Target Fixation) and the three measures of category knowledge for the 17-month-old group. However, significant associations between the measure of receptive vocabulary and all three measures of category knowledge were observed for the 25-month-old group. A strong negative association was observed between Average Target Fixation and Average Other-Category Fixation (r(35) = -. 82, p < .001). Again, this indicates a reciprocal relationship between average time spent looking to the target object and average time spent looking to one of the four other-category objects. A strong positive association was observed between Average Target Fixation and the NRuns ratio (r(35) = .70 , p < .001). This finding indicates that as toddlers increased time spent looking to the target item, they also increased the proportion of runs that they made within the target category. Finally, a moderate to low positive association between Average Target Fixation and MRL ratio was observed (r(35) = .33, p = .05). This indicates that as toddlers increased the proportion of time spent looking to the target object, they also increased the length of runs they made between objects belonging to the target category compared to items belonging to the other superordinate category.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix examining relationships between visual attention distribution and systematic scanning variables of the VAT for the 17- and 25-month-old cross-sectional samples.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Average Target Fixation | - | −.82** | .70** | .33* |

| (2) Average Other-Category Fixation | −.34 | - | −.71** | −.49** |

| (3) Number of Runs Ratio | −.12 | −.60** | - | .27 |

| (4) MRL Ratio | .75 | −.52* | −.05 | - |

correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed)

correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed)

Note: Pearson’s correlations for the 17-month-old group are displayed on the bottom of the chart and Pearson’s correlations for the 25-month-old group are displayed on the top of the chart; MRL = Mean Run Length.

3.3. Stability of Experimental Measurement Across Time

3.3.1. Does the VAT capture developmental change over time?

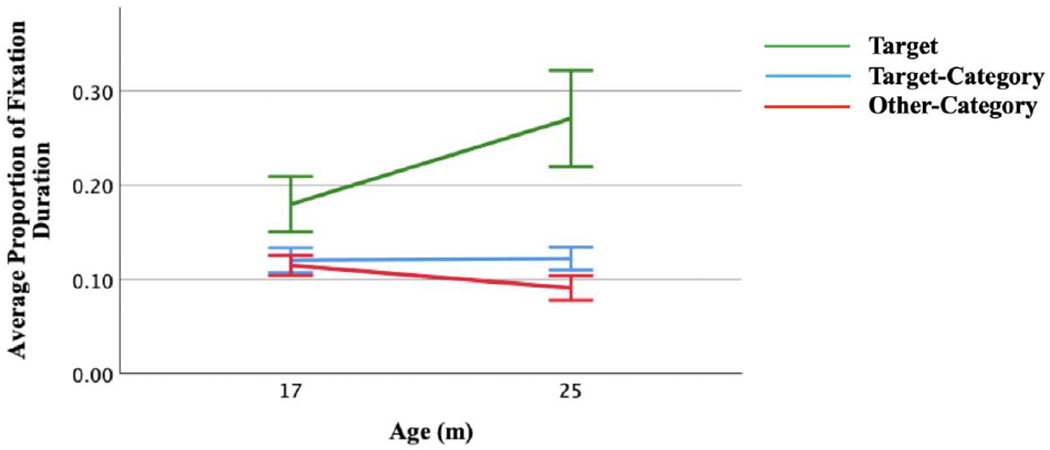

Toddlers in the longitudinal cohort demonstrated approximately a 9% increase in their proportion of target fixation duration between 17 (M = 0.18, SD = 0.05) and 25 (M = 0.27, SD = 0.08) months of age. A paired samples t-test confirmed that between 17 and 25 months these toddlers demonstrated a developmental increase in average target fixation duration (t(12) = -4.98, p < .001). This task also measured a corresponding decrease in average other-category object fixation across age (t(12) = 3.94, p = .002). Importantly, there were no observed differences in average looking to the other objects belonging to the target-category across age (t(12) = -.24, p = .82). This indicates a reciprocal relationship between time spent looking to the target and time spent looking to objects belonging to the other superordinate category. As toddlers increased preferential fixation of the target item they selectively decreased their attention to the other-category items (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Developmental trajectories of Average Target Fixation, Average Target-Category Fixation, and Average Other-Category Fixation for the longitudinal cohort. Error bars represent: 95% confidence interval.

3.3.2. Does performance on variables derived from the VAT at 17 months of age correlate with performance at 25 months of age?

To assess how well the experimental measure tracks receptive vocabulary growth relative to the standardized measure of the MSEL a correlation matrix including the same variables listed above was calculated using data from the longitudinal cohort. A significant positive correlation was observed for the VAT between Average Target Fixation measured at 17 months of age and 25 months of age (r(11) = .61, p = 0.03). Conversely, a significant correlation was not observed between scores collected at 17 and 25 months of age for the receptive language subscale of the MSEL (r(10) = .38, p = 0.23).

3.3.3. Do patterns of sequential looking change across development?

Paired samples t-tests were calculated for NRuns target category, NRuns other-category, MRL target category, and MRL other-category to determine if toddlers in the longitudinal cohort demonstrated an increase in the tendency to engage in sequential looking between 17 and 25 months of age. Results indicated that between 17 and 25 months of age toddlers increased their tendency to make runs within the target category (t(12) = -3.99, p < .01) and decreased the length of runs they made within the other-category (t(12) = 3.57, p < .01).

4. Discussion

4.1. Visual Attention Distribution

This study was the first to explore the feasibility of expanding the intermodal preferential looking paradigm (IPLP, Golinkoff et al., 1987) to include a large item array. Despite the added complexity, toddlers preferentially fixated a target item from among seven distractors. The successful expansion of this task helps eliminate concerns surrounding mutual exclusivity and the potential impact of perceptual similarity inherent in the two-item, forced-choice paradigms. As such, the VAT has the potential to be a more sensitive measure of language comprehension. The expansion of the item array also allowed for exploration of the developmental relationship between receptive vocabulary and category knowledge. Results indicated that toddlers directed their attention away from items that did not belong to the same category as the labelled item, suggesting a recognition of the superordinate category contrasts tested (see, Mareschal & Quinn, 2001).

Additionally, it was predicted that the VAT would demonstrate convergent validity with a standardized measure of receptive language such as the MSEL. However, no associations were observed between the measure of average target fixation and the receptive language subscale of the MSEL at either 17 or 25 months of age. In contrast, there was an association observed between category knowledge (i.e., less looking at non-target category members) and the receptive language subscale of the MSEL at 25 months of age indicating that toddlers who looked longer at the non-target category members had lower receptive language subscale scores.

The general lack of an observed relationship between the two measures is not all-together unexpected when the underlying constructs of each are taken into consideration. First, the MSEL requires that children meet both a basal and ceiling level of performance for each of the five subscales. This ensures that the assessment captures the full range of developmental capabilities of the child. For the VAT, items were chosen to maximize the likelihood that toddlers would know and therefore preferentially fixate the target objects. It is possible that a number of children reached ceiling level performance on the VAT, thus limiting variability. This may have created a discrepancy between the levels of developmental competency measured by the two assessments. Hence, future research using the procedure to test a greater number of words may yield significant. The second possibility is that, as an experimenter-administered assessment, the receptive language subscale of the MSEL requires a high level of behavioral response from the participant. To demonstrate underlying language comprehension children are asked to respond to prompts such as “where is the door?” or actively point to line drawings in a stimulus book. It is possible that the MSEL is simply under reporting language comprehension abilities compared to the VAT in children of these ages. Future research is needed to better understand the relationship between and relative strengths of these procedures.

4.2. Systematic Scanning

This was the first study to explore whether sequential touching behaviors observed in object manipulation tasks might translate to sequential looking behaviors during a gazed-based task. Results indicated that toddlers engage in sequential looking behaviors when presented with a visual array of objects that belong to two different superordinate categories. An age effect indicated that between 17 and 25 months of age, toddlers increased the number of runs made within the target category and decreased the length of runs made between objects of the other category.

An impact of the verbal target label was also noted. At 17 months of age, children preferentially made sequential visits to objects within the target category. At 25 months of age, toddlers maintained this preference for making runs within the target category but also demonstrated a preference for making shorter runs between other-category objects. Future research should explore the tendency of children to engage in sequential looking in the absence of a verbal prompt. This would more closely mirror traditional tasks of object manipulation where children are presented with real objects but given no explicit instructions (Mandler et al., 1987; Ricciuti, 1965; Starkey, 1981).

4.3. Stability of Experimental Measurement Across Time

A developmental improvement in receptive vocabulary is expected between 17 and 25 months of age. Thus, if the VAT is reflective of underlying object label knowledge, toddlers should demonstrate greater preferential fixation of the target at 25 versus 17 months of age. And indeed, this result was found for the longitudinal cohort. While toddlers at both ages preferentially fixated the labeled target, the percent of time they looked at the target significantly increased from the younger to older age.

Category knowledge also improves between 17 and 25 months of age. This knowledge may be reflected in attention distribution as either a preference to look to members of the target category and/or inhibit looking to members of the other superordinate category. Thus, toddlers were expected to demonstrate a reduction in average other-category object fixation between 17 and 25 months of age. Again, this was the pattern identified in the longitudinal cohort, suggesting an improvement in category knowledge across development.

4.4. General Discussion

The present study was the first to explore the feasibility of expanding the IPLP to an eight-item array, referred to here as the visual array task (VAT). As predicted, toddlers preferentially fixated a labeled target object embedded among seven distractors at both 17 and 25 months of age as well as demonstrated a developmental increase in target fixation across age. Furthermore, a strong correlation was found between performance at 17 months of age and 25 months of age suggesting consistency of measurement over time. In fact, this association was stronger for the measure of target identification derived from the VAT than the receptive language subscale of the MSEL. This supports the feasibility of using visual attention to measure receptive vocabulary outside of the forced-choice paradigm. Successfully identifying the target object (e.g. hat) from both same category members (e.g. pants, a shirt, and a shoe) and other-category members (e.g. a banana, bread, an apple or a cookie) requires a more accurate understanding of word-comprehension than identifying a target object from a single alternative. Therefore, the VAT has the potential to provide a more confident assessment of receptive vocabulary by demonstrating that toddlers are able to reliably identify target objects from a larger array of items containing both category and non-category members.

Evidence from visual paired preference tasks suggest that a sensitivity to superordinate categories develops around three to four months of age (Mareschal & Quinn, 2001). While the current study did not test infants that young, data does indicate an understanding of superordinate category membership at 17 months of age. An increase in object category knowledge was also captured between 17 and 25 months of age. As discussed above, as toddlers spent more time looking to the target object, they reduced the amount of time spent looking to the other-category objects. This suggests that labeling the target object draws visual attention to the target as well as categorically similar objects within the array, thus indicating a conceptual understanding of their category relationship.

By expanding the visual stimuli to an eight-item array, the VAT also allowed for the examination of category understanding through a measure of sequential looking. Findings from Mandler and Bauer (1988) suggest that toddlers as young as 20 months of age will sequentially touch members of the same category when presented with eight miniatures representing objects belonging to two distinct superordinate categories (e.g. animals versus vehicles). The current study was the first to explore whether this tendency to engage in sequential touching of category members would also extend to patterns of sequential looking between category members. An indication of superordinate category knowledge was reflected in a preference for sequentially looking to two or more objects belonging to the target category at 17 months of age. By 25 months of age an underlying understanding of superordinate categories was also indicated by a preference for making longer sequences of looks between target category members than other-category members. This suggests that despite potential interference from the verbal target label, toddlers do engage in sequential looking behaviors akin to the sequential touching behaviors observed in object manipulation tasks.

The ability of the VAT to measure both receptive vocabulary and object category knowledge provides a unique opportunity to examine the developing relationship between these two competencies within the context of the same task. Fulkerson and Waxman (2007) assert that as toddlers expand their receptive vocabularies, they are also better able to identify commonalities between objects belonging to the same category. Data reported here support this argument. The reciprocal relationship between the distribution of attention to the target object and the other-category items suggests that as word comprehension increases so does category knowledge. Significant correlations indicating a relationship between measures of target identification and category knowledge observed at 25 months of age further bolster this claim. Overall, results indicated that the tested VAT has the potential to measure receptive vocabulary as well as category knowledge within the context of a single gaze-based assessment.

This work represents an initial step toward the development of a more sensitive, attention-based measure of receptive vocabulary. Results reported here support the viability of using a multi-item visual array to assess the development of both word comprehension and related competencies such as category knowledge in toddlers. Future work should look to continue to refine and extend this paradigm in a number of different ways.

First, while the current iteration of the VAT utilized an eight-item array, the impact of the number of items included in the array was not assessed. Although toddlers demonstrated the ability to preferentially fixate a target item from among seven distractors, an upward limit of array size was not tested. It may be the case that toddlers continue to successfully fixate a target item when presented with arrays including ten, twelve, or even more items. The ability to include a greater number of distractor items may improve specificity of receptive language assessment. Conversely, the additional visual complexity of larger stimulus arrays may limit interpretability of scanning patterns or the types of analytic approaches that may be used to characterize task performance. Future work should explore variations in array size in order to determine the number of distractor items that produces the optimal balance between specificity of word knowledge and interpretability of visual scanning patterns.

However, even at the tested size of eight, the array used in the VAT allows for a faster and more comprehensive evaluation of vocabulary knowledge than that of the two-item forced-choice paradigms. Despite the limited number of words and category contrasts tested, a number of interesting results were produced which validate the feasibility of expanding the VAT into a more exhaustive assessment measure. By shortening the presentation length of each trial to perhaps five seconds, significantly more words could be tested during a short, approximately ten-minute, session. This represents a substantial reduction in time required for testing compared to standardized measures of receptive language such as the MSEL which can take upwards of an hour to administer.

Relatedly, while the current iteration of the VAT tested target words within the context of superordinate category relationships, future iterations have the potential to included distractors that vary on any number of dimensions of interest. Unlike current attention-based paradigms, the VAT allows experimenters increased opportunity to probe how precisely vocabulary words are understood by systematically varying relationships between the target item and multiple distractor items both within and across trials. For example, in very young children, typicality has been found to influence whether an object label will be associated with a specific exemplar (Arias-Trejo & Plunkett, 2010; Meints, Plunkett, & Harris, 1999). However, to date, these findings have relied on a two-item forced-choice paradigm limiting testing procedures to only the direct comparison of two exemplars at a time. This requires the use of numerous trials to carefully manipulate exemplar typicality until a threshold is reached where children no longer generalize a “known” object label. In the context of the VAT, experimenters have the opportunity to test relationships between multiple exemplars within a single trial. Those interested in better understanding the role of exemplar typicality on object label generalizations may choose, for example, items belonging to a single subordinate category, such as dog, that vary on degrees of typicality (perhaps ranging from Labrador Retriever, high typicality, to Beagle, medium typicality, to Chihuahua, low typicality). By comparing relative amounts of preferential looking to exemplars included in each array or across variations in arrays, experimenters can gain a more nuanced understanding of the stability of these object-label associations than is possible using the all-or-nothing analytic approach of force-choice paradigms.

Finally, as an initial study of a procedural concept, this work also had a number of limitations. In order to determine whether children could successfully identify a target object from a larger array of eight items, the objects included in the present stimuli were carefully chosen to represent vocabulary words that children of the tested age ranges would be reasonably expected to know. While this increased the likelihood that toddlers would indeed preferentially fixate the target object within the larger eight item array, it also may have resulted in a number of participants reaching ceiling performance. This reduction in performance variability may have led to the inability of the task to capture differences in target identification at 25 months of age. Future iterations of the task should include both known and unknown vocabulary words.

Similarly, unlike traditional tasks of object manipulation, this task did not provide participants with the opportunity to freely explore (visually scan) the objects on the screen prior to target label onset. Thus, the scan patterns of participants were likely influenced by knowledge of the target category. In a way, this transformed the task from the “free-play” encouraged in object manipulation paradigms to a form of visual search. Future iterations of the task should explore the impact of variations in the temporal window between presentation of the visual array and accompanying auditory prompt. The optimal window between visual and auditory stimulus onset will be of particular importance, and likely vary greatly, depending on the primary goal of the assessment. In the present study, category knowledge was assessed using a measure of sequential looking based on analytic methods used in traditional tasks of object manipulation (Mandler et al., 1987; Ricciuti, 1965; Starkey, 1981). Interpretation of these analyses would have benefitted from a delay between visual array presentation and verbal labeling of the target object (i.e. by better approximating traditional object manipulation paradigms). However, simultaneous presentation of the visual and auditory stimulus would be preferable for examining the time course of language comprehension in infants and young children that relies on more fine-grained temporal analyses of visual fixation patterns.

Overall, results indicated that the tested visual array task may be both a sensitive measure of receptive vocabulary as well as capable of reflecting gains in category knowledge. This paradigm has the potential to be developed into an inexpensive and efficient task that places few behavioral demands on the participant. As is true of the IPLP and the LWL procedure, the VAT also allows for flexibility in the design of its stimulus arrays. The particular iteration of the VAT used in this study tested receptive vocabulary knowledge, or to be more precise, object noun labels, as well as a superordinate category contrast. However, the general design of the task allows for the flexibility to test any number of lexical constructs or category contrasts. Once this task is developed into a standardized form it may be particularly useful in testing for receptive vocabulary or category understanding delays in atypically developing or developmentally delayed populations. As it requires no overt gestural or expressive language response, it can be administered across the developmental spectrum including preverbal infants and non-verbal adults.

Research Highlights.

A novel gaze-based measure, the visual array task (VAT), was developed to assess object label and category knowledge in 17- and 25- month-old infants.

The tested VAT was capable of reflecting expected developmental gains in receptive vocabulary and category knowledge.

Correlations between VAT performance at 17 and 25 months of age were stronger than those of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning receptive language subscale.

The VAT is a simple and efficient task for measuring receptive language development and its relationship to category development.

Acknowledgements:

This work was funded by NIH grant P50-HD055748.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Kathryn M. Hauschild declares that she has no conflict of interest. Anamiguel Pomales-Ramos declares that she has no conflict of interest. Mark S. Strauss declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Arias-Trejo N, & Plunkett K (2010). The effects of perceptual similarity and category membership on early word-referent identification. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 105(1–2), 63–80. 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N (1993). Bayley scales of infant development: Manual. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Brady NC, Anderson CJ, Hahn LJ, Obermeier SM, & Kapa LL (2014). Eye tracking as a measure of receptive vocabulary in children with autism spectrum disorders. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30(2), 147–159. 10.3109/07434618.2014.904923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L (2002). MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson B, & Waxman S (2017). Linking language and categorization in infancy. Journal of child language, 44(3), 527–552. 10.1017/S0305000916000568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Pinto JP, Swingley D, Weinbergy A, & McRoberts GW (1998). Rapid gains in speed of verbal processing by infants in the 2nd year. Psychological Science, 9(3), 228–231. 10.1111/1467-9280.00044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Zangl R, Portillo AL, & Marchman VA (2008). Looking while listening: Using eye movements to monitor spoken language. Developmental psycholinguistics: On-line methods in children’s language processing, 44, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson AL, & Waxman SR (2007). Words (but not tones) facilitate object categorization: Evidence from 6-and 12-month-olds. Cognition, 105(1), 218–228. 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K, Cauley KM, & Gordon L (1987). The eyes have it: Lexical and syntactic comprehension in a new paradigm. Journal of child language, 14(1), 23–45. 10.1017/S030500090001271X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golinkoff RM, Ma W, Song L, & Hirsh-Pasek K (2013). Twenty-five years using the intermodal preferential looking paradigm to study language acquisition: What have we learned?. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(3), 316–339. 10.1177/1745691613484936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golinkoff RM, Mervis CB, & Hirsh-Pasek K (1994). Early object labels: the case for a developmental lexical principles framework [*]. Journal of child language, 21(1), 125–155. 10.1017/S0305000900008692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston-Price C, Mather E, & Sakkalou E (2007). Discrepancy between parental reports of infants’ receptive vocabulary and infants’ behaviour in a preferential looking task. Journal of Child Language, 34(4), 701–724. 10.1017/S0305000907008124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law J, & Roy P (2008). Parental report of infant language skills: A review of the development and application of the Communicative Development Inventories. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(4), 198–206. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mareschal D, & Quinn PC (2001). Categorization in infancy. Trends in cognitive sciences, 5(10), 443–450. 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01752-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman EM, & Wachtel GF (1988). Children’s use of mutual exclusivity to constrain the meanings of words. Cognitive psychology, 20(2), 121–157. 10.1016/0010-0285(88)90017-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler JM, & Bauer PJ (1988). The cradle of categorization: Is the basic level basic?. Cognitive development, 3(3), 247–264. 10.1016/0885-2014(88)90011-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler JM, Bauer PJ, & McDonough L (1991). Separating the sheep from the goats: Differentiating global categories. Cognitive Psychology, 23(2), 263–298. 10.1016/0010-0285(91)90011-C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler JM, Fivush R, & Reznick JS (1987). The development of contextual categories. Cognitive Development, 2(4), 339–354. 10.1016/S0885-2014(87)80012-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meints K, Plunkett K, & Harris PL (1999). When does and ostrich become a bird? The role of typicality in early word comprehension. Developmental Psychology, 35(4), 1072 10.1037/0012-1649.35.4.1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, & Bertrand J (1994). Acquisition of the novel name–nameless category (N3C) principle. Child development, 65(6), 1646–1662. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EM (1995). Mullen scales of early learning (pp. 58–64). Circle Pines, MN: AGS. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson P (2007). Real-time and offline filters for eye tracking. Msc thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, April [Google Scholar]

- Ricciuti HN (1965). Object grouping and selective ordering behavior in infants 12 to 24 months old. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly of Behavior and Development, 11(2), 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ross GS (1980). Categorization in 1-to 2-yr-olds. Developmental Psychology, 16(5), 391. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch E (1978). Principles of categorization Cognition and categorization, ed. by Eleanor Rosch & Barbara B. Lloyd, 27–48. 10.1037/0012-1649.16.5.391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey D (1981). The origins of concept formation: Object sorting and object preference in early infancy. Child Development, 489–497. DOI: 10.2307/1129166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, & Mervis CB (1994). The instrument is great, but measuring comprehension is still a problem. Monographs of the Society for Research in child Development, 59(5), 174–179. 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb00186.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SR, & Markow DB (1995). Words as invitations to form categories: Evidence from 12-to 13-month-old infants. Cognitive psychology, 29(3), 257–302. 10.1006/cogp.1995.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]