Abstract

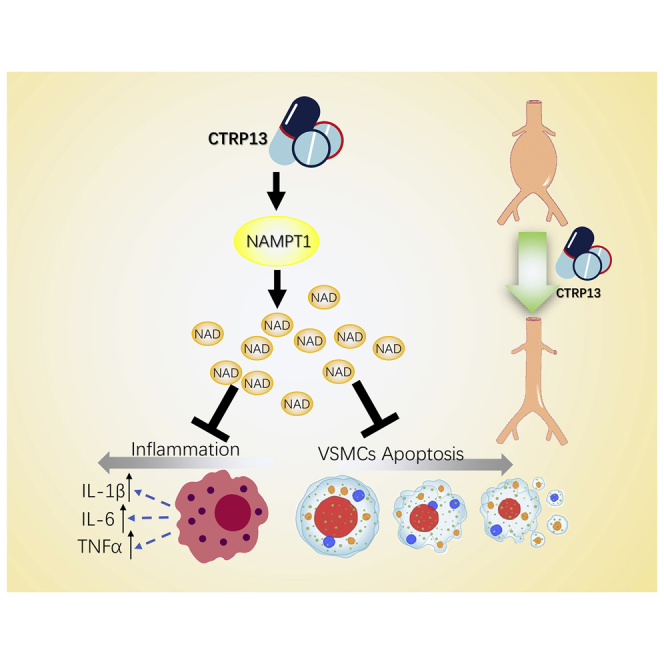

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening cardiovascular disease characterized by localized dilation of the abdominal aorta. C1q/tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related protein-13 (CTRP13) is a secreted adipokine that plays important roles in the cardiovascular system. However, the functional role of CTRP13 in the formation and development of AAA has yet to be explored. In this study, we determined that serum CTRP13 levels were significantly downregulated in blood samples from patients with AAA and in rodent AAA models induced by Angiotensin II (Ang II) in ApoE−/− mice or by CaCl2 in C57BL/6J mice. Using two distinct murine models of AAA, CTRP13 was shown to effectively reduce the incidence and severity of AAA in conjunction with reduced aortic macrophage infiltration, expression of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-6 [IL-6], TNF-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1]), and vascular smooth muscle cell (SMC) apoptosis. Mechanistically, nicotinamide phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (NAMPT1) was identified as a new target of CTRP13. The decreased in vivo and in vitro expression of NAMPT1 was markedly reversed by CTRP13 supplementation in a ubiquitination-proteasome-dependent manner. NAMPT1 knockdown further blocked the beneficial effects of CTRP13 on vascular inflammation and SMC apoptosis. Overall, our study reveals that CTRP13 management may be an effective treatment for preventing AAA formation.

Graphical Abstract

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening cardiovascular disease. This study reported that CTRP13, a secreted adipokine, reduces the incidence and severity of AAA in conjunction with reduced aortic macrophage infiltration and proinflammatory response. CTRP13 management may be an effective treatment for preventing AAA formation.

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), a life-threatening condition, is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in developed countries and is most common in the population over 65 years of age.1, 2, 3, 4 The pathological features of AAA are vascular matrix degradation, reactive oxygen species accumulation, vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) dedifferentiation/apoptosis, and the infiltration of inflammatory cells, which causes weakening of the aortic wall and consequent progressive vessel dilation, rupture, and death.5, 6, 7, 8 Currently, the forms of treatment for AAA are endovascular aortic repair or open surgical repair, which are associated with ineffective extension of long-term survival and postoperative mortality, respectively.9,10 Thus, further exploration of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying AAA progression is crucial in the development of new and effective therapeutic strategies.

Emerging evidence indicates that adipokines, which are predominantly secreted by adipocytes, may have beneficial effects in controlling cardiovascular homeostasis, energy balance, inflammatory responses, and insulin sensitization.11,12 Currently, accumulating evidence indicates that multiple adipokines are involved in the regulation of AAA. Adiponectin, a key adipokine that functions in various diseases, protects against Angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced vascular inflammation and AAA formation in mice.13 Moreover, adipocyte-secreted apelin significantly inhibited aneurysm formation in an elastase model of human AAA disease by decreasing the macrophage burden, which was related to a decrease in proinflammatory factor activation.14 In contrast, periaortic application of recombinant leptin in Ang II-treated ApoE−/− mice exacerbated extracellular matrix digestion and aneurysmal dilation of the aortic wall.15 However, the precise roles of adipokines in the regulation of AAA remain incompletely characterized.

C1q/tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related proteins (CTRPs) are new members of the conserved adiponectin family that play pleiotropic roles in modulating the physiology and pathophysiology of the metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune systems.16 Among the 15 identified C1q/TNF-related proteins, C1q/TNF-related protein-13 (CTRP13) is highly evolutionarily conserved, with only a single amino-acid difference between the mouse and human proteins.17 It was reported that CTRP13 could improve glucose metabolism in adipocytes, hepatocytes, and myotubes.17 Our recent study suggested that serum CTRP13 was highly associated with endothelial dysfunction in diabetes and that ectopic CTRP13 infusion dramatically preserved endothelial function in diabetic mice.18 In addition, we found that CTRP13 supplementation inhibited the osteogenic differentiation of SMCs, thus reducing calcium deposition in chronic kidney diseases.19 However, the roles of CTRP13 in AAA and its potential therapeutic effect against AAA formation remain elusive. In this study, we focused on the role and the underlying mechanism of CTRP13 in Ang II- or CaCl2-induced AAA mouse models.

Results

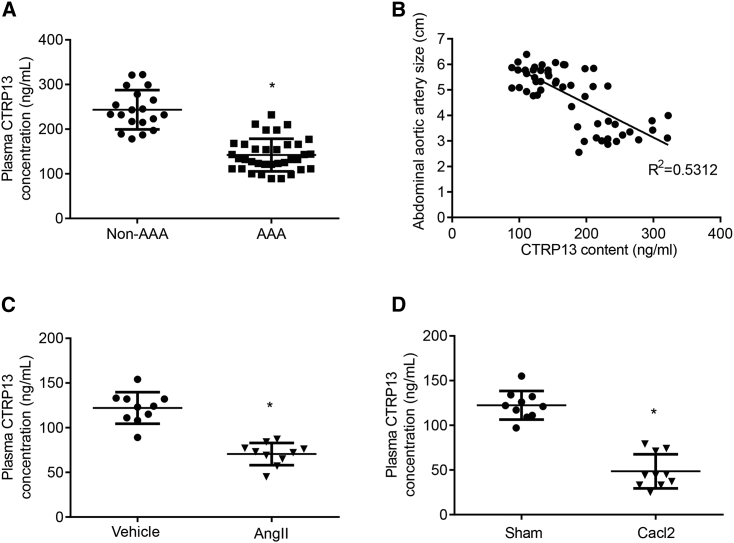

Plasma CTRP13 Levels Are Decreased during AAA Development

To examine whether CTRP13 was associated with AAA in patients, we first collected serum samples from patients with AAA and healthy volunteers (non-AAA) and discovered that the CTRP13 levels in the AAA group were lower than those in the non-AAA group (Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 1B, a negative correlation was found between the CTRP13 concentration and AAA size (R2 = 0.5312, p < 0.05; n = 54), suggesting that the serum CTRP13 level was strongly negatively associated with the progression of AAA. Next, we measured CTRP13 levels in rodent AAA models. As previously described, we established an Ang II-induced AAA model by slowly infusing Ang II or vehicle into ApoE−/− mice with a minipump for 4 weeks. The CaCl2-induced mouse AAA model was established by treating C57BL/6J mice with CaCl2- or vehicle-containing gauze for 15 min during surgery (Figure S1). As shown in Figures 1C and 1D, along with AAA formation in the aorta, the levels of circulating CTRP13 were decreased compared with those in the control group. These data indicate that decreased serum CTRP13 levels might be associated with AAA formation in mice and humans.

Figure 1.

Plasma CTRP13 Levels Are Decreased during AAA Development

(A) Serum CTRP13 levels in patients with AAA (n = 35) and in volunteers without AAA (n = 19). Data were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. (B) The size of abdominal aortic artery and the serum CTRP13 levels were negatively correlated. R2 = 0.5312, p < 0.05; n = 54. (C) The concentration of CTRP13 in ApoE−/− mice infused with Ang II for 4 weeks. n = 10 per group. Data were analyzed with unpaired Student’s t test. (D) The concentration of CTRP13 in C57BL/6J mice after CaCl2-containing gauze treatment for 4 weeks. n = 10 per group. Data were analyzed with unpaired Student’s t test. Data are presented as means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05.

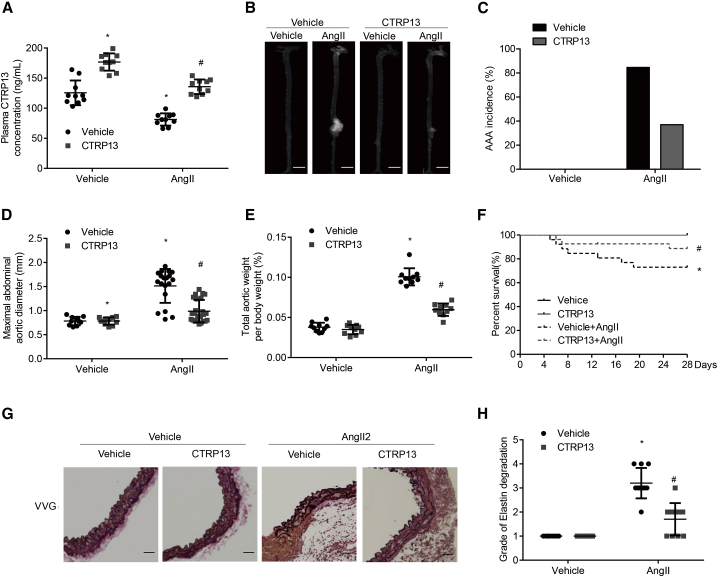

CTRP13 Prevents Ang II-Induced AAA Progression in ApoE−/− Mice

Then, we explored the role of CTRP13 supplementation in the Ang II-induced experimental AAA model in ApoE−/− mice. Recombinant CTRP13 was administered to mice via intraperitoneal injection every other day for 4 weeks, which successfully increased the plasma levels of CTRP13 (n = 25–30 per group) (Figure 2A). Ang II infusion increased systolic blood pressure in ApoE−/− mice, but there was no obvious change in systolic blood pressure in the mice after CTRP13 supplementation (Figure S2A). CTRP13 treatment mitigated generalized aortic dilation and decreased the incidence of AAA by 47.6%, compared with those of the Ang II group (Figures 2B and 2C). Ang II infusion significantly increased the ratio of aortic weight to body weight and the maximal abdominal aortic diameter in ApoE−/− mice, while these effects were significantly alleviated by CTRP13 supplementation (Figures 2D and 2E). Regarding mortality, within the initial 28 days of treatment, 26.9% of Ang II-infused ApoE−/− mice died as a result of aortic rupture, whereas 3 deaths (11.1%) occurred in mice treated with CTRP13 (200 μg/kg; Figure 2F). The histological features of AAA were analyzed, and Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining showed that CTRP13 treatment reversed the frequent disruption and degradation of the elastic lamina in Ang II-infused ApoE−/− mice (Figures 2G and 2H). Thus, ectopic CTRP13 infusion alleviated Ang II-induced AAA formation in vivo.

Figure 2.

CTRP13 Decreases AAA Progression in Ang II-Treated ApoE−/− Mice

ApoE−/− mice that had been infused with vehicle (normal saline) or Ang II were then treated with or without recombinant CTRP13 (200 μg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection every other day for 4 weeks (ns = 10, 10, 26, and 27). (A) Plasma CTRP13 levels in the mice (n = 10). (B) Representative photographs showing macroscopic features of AAA in ApoE−/− mice. Scale bars, 2.5 mm. (C) Incidence of AAA in different groups. %, the number of animals with successfully experimental AAA relative to the total number of animals. (D–F) Maximal abdominal aortic diameter (D), the ratio of aortic weight to body weight (E), and Kaplan-Meier survival curves from the four groups (F). (G) Representative Verhoeff-Van Gieson (VVG) staining. Scale bars, 50 μm. n = 10. (H) Elastin degradation score in suprarenal aortas from the 4 groups (n = 10). Vehicle, vehicle infusion; Ang II, Ang II infusion for 4 weeks; CTRP13, CTRP13 injection for 4 weeks; Ang II+CTRP13, CTRP13 plus Ang II infusion for 4 weeks. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle; #p < 0.05 versus Ang II.

CTRP13 Prevents AAA Formation in CaCl2-Treated C57BL/6J Mice

Next, to verify whether CTRP13-mediated modulation of AAA formation was consistent among other mouse models of AAA, we treated the well-accepted CaCl2-induced AAA model with CTRP13 injection (n = 10–12 per group). The plasma CTRP13 level was 41% higher in CTRP13-treated AAA mice than in vehicle-treated AAA mice (Figure 3A). Consistent with the aforementioned findings, 4 weeks after CaCl2-induced AAA surgery, CTRP13 supplementation reduced the enlargement of abdominal aortas (Figure 3B). The total aortic weights and maximal abdominal aortic diameters were also obviously decreased in the CTRP13 group compared with those in the vehicle group (Figures 3C and 3D). Along with AAA formation, a substantial decrease in the elastin degradation score was observed in the CTRP13 group, as shown by Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining (Figures 3E and 3F). Taken together, these results suggested that CTRP13 treatment reduced the severity of CaCl2-induced AAA in C57BL/6J mice.

Figure 3.

CTRP13 Attenuates AAA Progression in CaCl2-Treated C57BL/6J Mice

C57BL/6J mice, pre-treated with CaCl2 or vehicle, were intraperitoneally injected with or without recombinant CTRP13 (200 μg/kg) for 4 weeks (n = 10 mice per group). (A) Plasma CTRP13 levels in the mice (n = 10). (B) Representative photographs showing macroscopic features of AAA in male C57BL/6J mice. Scale bars, 3.5 mm. (C and D) Maximal abdominal aortic diameter (C) and the ratio of aortic weight to body weight (D) from the four groups. (E) Representative VVG staining. Scale bars, 50 μm. n = 10. (F) Elastin degradation score in suprarenal aortas from the 4 groups (n = 10). Vehicle, vehicle (normal saline) treatment; CaCl2, CaCl2 treatment; CTRP13, CTRP13 injection for 4 weeks; Ang II+CTRP13, CaCl2 treatment plus CTRP13 injection for 4 weeks. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle; #p < 0.05 versus CaCl2.

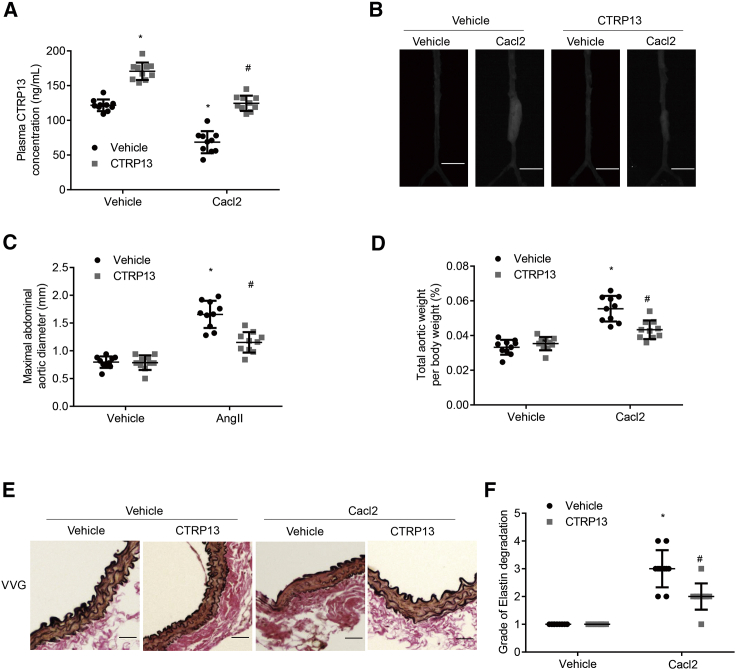

CTRP13 Reduces Macrophage Infiltration and the Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines In Vivo and In Vitro

Chronic inflammation of the vessel wall and macrophage infiltration are major pathological features of AAA.20 In the present study, the accumulation of inflammatory cells and the expression of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, TNF-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) were measured to compare the inflammatory states of mice in the different groups. Relative to those in the Ang II-infused or CaCl2-treated group, CTRP13 treatment markedly mitigated macrophage infiltration and protein expression of IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 (Figures 4A–4D). In cultured macrophages, Ang II incubation substantially enhanced the mRNA expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in comparison with those in the vehicle group, but this effect was reduced by CTRP13 supplementation (Figure 4E). These data indicated that CTRP13 inhibited macrophage infiltration and inflammatory reactions in the development of AAA.

Figure 4.

Effects of CTRP13 on Macrophage Infiltration and Inflammatory Cytokine Expression In Vivo and In Vitro

(A) Representative CD68 immunofluorescence staining of the abdominal aortas from ApoE−/− mice treated with Ang II or Ang II+CTRP13 (n = 8). Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Representative western blot analysis of inflammatory markers (IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1) in abdominal aortas from the Ang II or Ang II+CTRP13 group (n = 8). (C) Representative CD68 immunofluorescence staining of the abdominal aortas from C57BL/6J mice with CaCl2 or CaCl2+CTRP13 (n = 5). Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) Representative western blot analysis of inflammatory markers (IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1) in abdominal aortas (n = 5). (E) Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in cultured macrophages in vitro (n = 5). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle; #p < 0.05 versus Ang II or CaCl2.

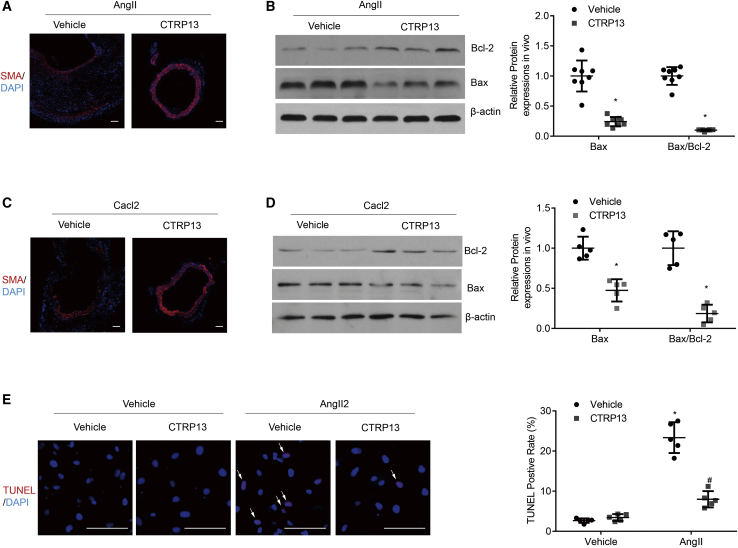

CTRP13 Reduces Apoptosis in Aortic Tissues and SMCs

A reduced number of SMCs is a striking pathological feature of AAA.8 To explore whether CTRP13 could alter the loss of SMCs in AAA, we first examined the SMC level in the abdominal aortic wall by immunofluorescence staining with an anti-α-SMA (smooth muscle actin) antibody. The relative decreases in SMC levels in the Ang II-treated and CaCl2-treated groups were statistically rescued after the addition of CTRP13 (Figures 5A and 5C).

Figure 5.

Effects of CTRP13 on SMC Apoptosis in Abdominal Aortic Tissues and Cultured SMCs

(A) Representative immunofluorescence staining of SMA in the abdominal aortas of ApoE−/− mice from the Ang II or Ang II+CTRP13 group (n = 8). Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Representative western blot analysis of apoptotic markers (Bax and Bcl-2) in SMCs isolated from abdominal aortas in AAA mice (n = 8). (C) Representative CD68 immunofluorescence staining of the abdominal aortas from CaCl2-treated C57BL/6J mice with or without CTRP13 treatment (n = 5). Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) Representative western blot analysis of apoptotic markers (Bax and Bcl-2) in isolated SMCs of abdominal aortas from the CaCl2 or CaCl2+CTRP13 group (n = 5). (E) Representative TUNEL images and quantitative analysis in cultured HASMCs with the indicated treatment (n = 5). Scale bars, 100 μm. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as the means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle; #p < 0.05 versus Ang II or Cacl2.

SMC apoptosis is an important pathological feature that leads to SMC loss in the development of AAA. To investigate the effects of CTRP13 on SMC apoptosis, the protein levels of Bcl-2 and Bax in SMCs isolated from abdominal aortic tissues were measured. In the Ang II-treated and CaCl2-treated mouse models, CTRP13 supplementation dramatically downregulated the expression of Bax compared with that in the Ang II or CaCl2 group (Figures 5B and 5D). As the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio is commonly used to quantitate the degree of apoptosis, we also measured this parameter in this experiment. Compared with that in the Ang II-treated and CaCl2-treated groups, the upregulated Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was significantly decreased after CTRP13 injection (Figures 5B and 5D). Moreover, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assays were performed in cultured human primary aortic SMCs (HASMCs). As shown in Figure 5E, Ang II treatment significantly increased SMC apoptosis, whereas CTRP13 incubation markedly attenuated the SMC apoptosis. Taken together, these results suggested that CTRP13 eliminated SMC apoptosis in vivo and in vitro.

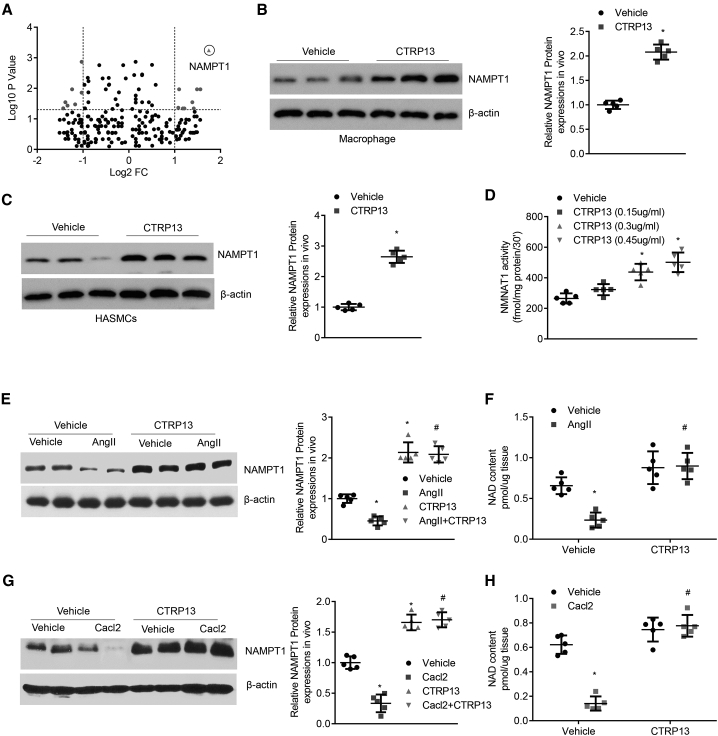

CTRP13 Positively Regulates the Levels of NAMPT1

To delineate the mechanism by which CTRP13 inhibited AAA formation, we examined alterations in proteins in the abdominal arteries of vehicle- and CTRP13-treated mice and used iTRAQ technology to analyze differentially labeled protein samples. A number of differentially expressed proteins were identified and analyzed by mass spectrometry (Figure 6A). Among them, nicotinamide phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (NAMPT1), a rate-limiting enzyme that converts nicotinamide to nicotinamide mononucleotide in all organisms,21 scored the highest on a list of divergent peptide hits. Rapidly accumulating evidence in the past decade shows that NAMPT1 activity and NAMPT1-controlled NAD metabolism regulate fundamental biological functions in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.22 Then, macrophages and HASMCs were treated with vehicle or CTRP13, and the protein extracts were subjected to western blot analysis. NAMPT1 expression was efficiently upregulated by CTRP13 incubation (Figures 6B and 6C). The activity of NAMPT1 exhibited a similar change after treatment with CTRP13. Compared with that in control cells, NAMPT1 activity in macrophages treated with CTRP13 (150, 300, and 450 ng/mL) increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6D). In the in vivo experiment, we found that the protein level of NAMPT1 was significantly decreased in Ang II-induced and CaCl2-treated AAA abdominal tissues. However, CTRP13 supplementation reversed the negative effects of Ang II or CaCl2 on NAMPT1 expression (Figures 6E and 6G). Furthermore, we assessed the level of NAD+, a biosynthetic metabolite of NAMPT1, in aortic samples from AAA mice and found that NAD+ levels changed in accordance with that of NAMPT1 expression in response to CTRP13 (Figures 6F and 6H).

Figure 6.

CTRP13 Upregulates the Levels of NAMPT1

(A) iTRAQ quantification of aortic extracts from vehicle (normal saline)- and CTRP13-treated mice. Volcano plot of the log10 (p values) as a function of log2 (protein fold change). The statistical significance (p value on a log10 scale) is plotted as a function of the protein fold change (on a log2 scale). (B) Western blot analysis of the expression of NAMPT1 in macrophages that were treated with vehicle or CTRP13 (300 ng/mL) for 24 h (n = 5). (C) Western blot analysis of the expression of NAMPT1 in HASMCs that were treated with vehicle or CTRP13 (300 ng/mL) for 24 h (n = 5). (D) Macrophages were treated with recombinant CTRP13 (0, 150, 300, and 450 ng/mL) for 24 h, and NAMPT1 activity was then detected with a commercial kit (n = 5). (E) The expression of NAMPT1 in the abdominal aortas from the Ang II or Ang II+CTRP13 group was determined by western blot assay. The results were normalized to the β-actin level (n = 5). (F) NAD+ content in the abdominal aortas was determined with a commercial kit (n = 5). (G) The expression of NAMPT1 in the abdominal aortas from the CaCl2 or CaCl2+CTRP13 group was determined by western blot assay. The results were normalized to the β-actin level (n = 5). (H) NAD+ content in the abdominal aortas was determined with a commercial kit (n = 5). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05 versus vehicle; #p < 0.05 versus Ang II or CaCl2.

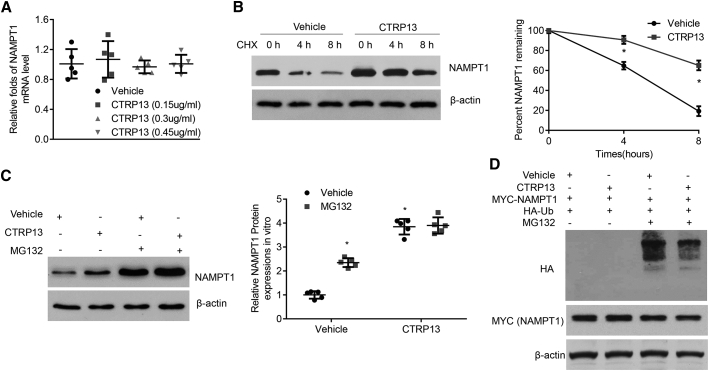

CTRP13 Inhibits the Degradation and Ubiquitination of NAMPT1

Next, we sought to investigate how CTRP13 upregulated NAMPT1 expression. As shown in Figure 7A and Figure S4A, the quantitative real-time PCR results showed that supplementation of macrophages and HASMCs with CTRP13 did not influence NAMPT1 mRNA levels compared with those of vehicle-treated cells, suggesting that CTRP13 regulated NAMPT1 at the posttranscriptional level. Then, we treated macrophages and VSMCs with cycloheximide to inhibit cellular protein synthesis. Interestingly, CTRP13 dramatically delayed the reduction in NAMPT1 protein levels (Figure 7B; Figure S4B), suggesting that the posttranscriptional regulation might be associated with protein degradation.

Figure 7.

CTRP13 Mediates the Protein Stability of NAMPT1

(A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of NAMPT1 mRNA levels in macrophages under CTRP13 (0, 150, 300, and 450 ng/mL) treatment (n = 5). (B) Macrophages pretreated with vehicle or CTRP13 (300 ng/mL) were incubated with cycloheximide (CHX; 1 mg/mL) for 0, 4, and 8 h. NAMPT1 protein levels were analyzed by western blot analysis (n = 5). (C) Macrophages incubated with vehicle or CTRP13 (300 ng/mL) were treated with 1 mM MG132 for 24 h or DMSO (vehicle) as a control. Western blot analysis of NAMPT1 protein levels in related cells (n = 5). (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-Ub and Myc-NAMPT1, with or without CTRP13 (300 ng/mL) supplementation, and then treated with MG132. Protein extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc beads and western blot analysis with anti-HA antibody (n = 5). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle; #p < 0.05 versus Ang II.

The ubiquitin (Ub)-proteasome pathway is a major system for intracellular protein degradation, and so we examined whether CTRP13 enhanced the expression of NAMPT1 by inhibiting its proteasomal degradation. Macrophages or HASMCs were pretreated with CTRP13 or vehicle and incubated with DMSO or MG132, a potent 26S proteasome inhibitor. An increase in NAMPT1 protein levels was observed in the CTRP13 group, similar to previous results, while MG132 treatment blocked CTRP13-mediated enhancement of NAMPT1 expression (Figure 7C; Figure S4C). We also measured NAMPT1 ubiquitination in the presence of CTRP13. As shown in Figure 7D, CTRP13 treatment dramatically decreased the polyubiquitination of exogenous NAMPT1. Accordingly, these data indicated that NAMPT1 was regulated by CTRP13 in a Ub-proteasome-dependent manner.

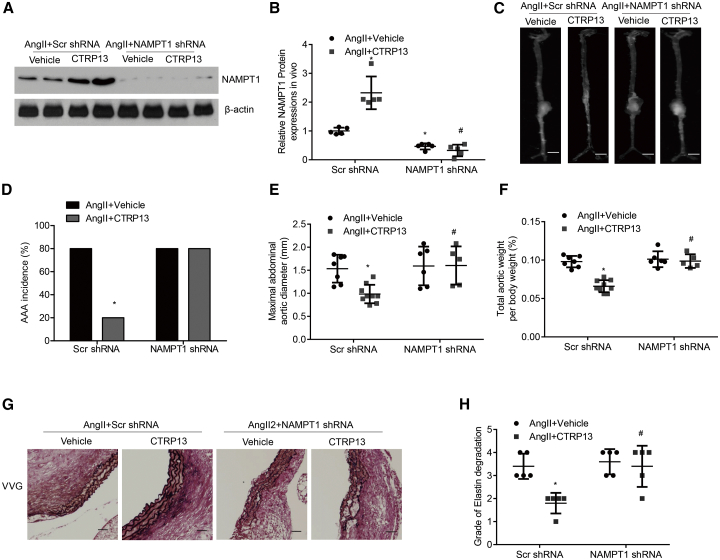

NAMPT1 Mediates the Effects of CTRP13 on the Progression of Ang II-Induced AAA

We next explored whether NAMPT1 signaling was involved in mediating the effects of CTRP13 on Ang II-induced AAA formation in ApoE−/− mice. We used a lentivirus carrying NAMPT1-knockdown constructs to inhibit NAMPT1 expression and the corresponding control viruses (n = 10 mice per group). Successful knockdown of NAMPT1 in AAA tissues was confirmed by western blot analysis (Figure 8A). As shown in Figures 8B–8D, in ApoE−/− mice, Ang II-induced AAA formation was prevented by CTRP13. However, this beneficial effect was not observed in the abdominal aortas from NAMPT1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-transduced mice. In addition, knockdown of NAMPT1 obviously abrogated the protective effect of CTRP13 on the ratio of aortic weight to body weight and the maximal abdominal aortic diameter in AAA mice (Figures 8E and 8F). In comparison with the survival rate of the vehicle group, CTRP13 greatly ameliorated the survival rate of Ang II-treated ApoE−/− mice. However, when NAMPT1 was silenced, the positive effects of CTRP13 were effectively reversed (Figure S6). Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining also showed that aortic wall thickening and disrupted medial elastin occurred more frequently in the Ang II + CTRP13 + NAMPT1 shRNA-treated groups than in other groups, but these changes occurred to a much lesser extent in the Ang II + CTRP13+Scr shRNA-treated group (Figures 8G and 8H), suggesting that NAMPT1, indeed, mediated the effects of CTRP13 on pathological remodeling of the aortic wall in AAA mice induced by Ang II.

Figure 8.

NAMPT1 Mediates the Effects of CTRP13 on the Development of Ang II-Induced AAA

Ang II-treated ApoE−/− mice were first transduced with Scr shRNA or NAMPT1 shRNA lentivirus and then were injected with or without recombinant CTRP13 for 4 weeks (n = 10 mice per group). (A and B) Western blot analysis (A) and quantification (B) of NAMPT1 protein levels in the abdominal aortas from the four groups (n = 5). (C) Representative photographs showing macroscopic features of AAA in male ApoE−/− mice. Scale bars, 2.5 mm. (D) Incidence of AAA in the four groups as indicated. %, the number of animals with AAA relative to the total number of animals. (E and F) Maximal abdominal aortic diameter (E) and the ratio of aortic weight to body weight (F) from the four groups (n = 10). (G) Representative VVG staining. Scale bars, 50 μm. n = 5. (H) Elastin degradation score in suprarenal aortas from the 4 groups (n = 5). Ang II+Vehicle+Scr shRNA, Scr shRNA transduction plus Ang II infusion for 4 weeks; Ang II+CTRP13+Scr shRNA, Scr shRNA transduction plus Ang II infusion, together with CTRP13 injection for 4 weeks; Ang II+Vehicle+NAMPT1 shRNA, NAMPT1 shRNA transduction plus Ang II infusion for 4 weeks; Ang II+CTRP13+NAMPT1 shRNA, NAMPT1 shRNA transduction plus Ang II infusion, together with CTRP13 injection for 4 weeks. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as the means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05 versus Ang II+vehicle+Scr shRNA; #p < 0.05 versus Ang II+CTRP13 +Scr shRNA.

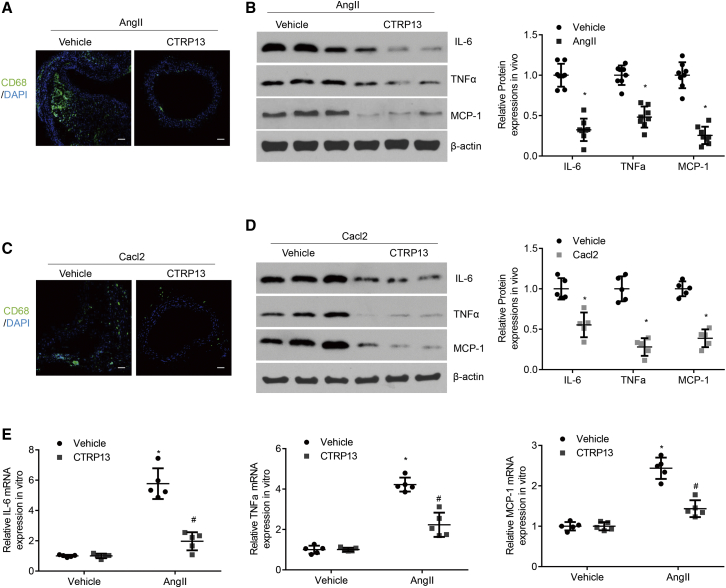

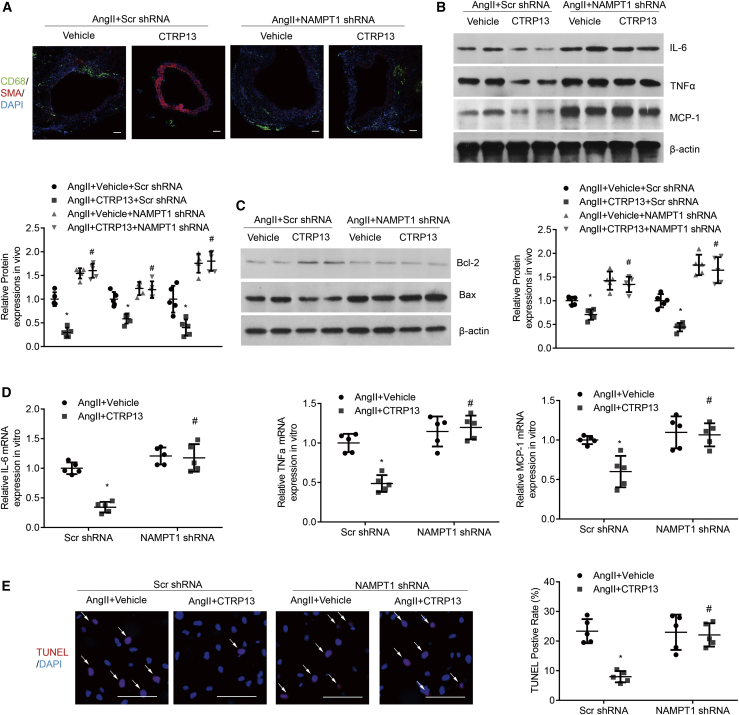

NAMPT1 Disruption Ameliorates the Effects of CTRP13 on Vascular Inflammation and Apoptosis

Then, we investigated the role of NAMPT1 in macrophage infiltration and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Immunofluorescence staining and western blot analysis showed that the decreases in the relative numbers of macrophages and the protein levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in the abdominal aortic wall after CTRP13 treatment in AAA mice were largely reversed by NAMPT1 knockdown (Figures 9A and 9B). In addition, NAMPT1 silencing abolished the protective effects of CTRP13 on VSMC apoptosis and loss in abdominal aortas (Figures 9A and 9C). In cultured macrophages in vitro, the Ang II-treatment-induced increases in the mRNA expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 were attenuated by CTRP13 supplementation, but this therapeutic effect was virtually offset when NAMPT1 was silenced (Figure 9D). TUNEL assays also confirmed the previous finding that NAMPT1 knockdown could effectively abolish the protective effects of CTRP13 on SMC apoptosis (Figure 9E). These data suggest the essential role of NAMPT1 in the regulation of CTRP13 in AAA.

Figure 9.

NAMPT1 Mediates the Effects of CTRP13 on Inflammatory and SMC Apoptosis In Vivo and In Vitro

Ang II-treated ApoE−/− mice were transduced with Scr shRNA or NAMPT1 shRNA lentivirus and then were injected with or without recombinant CTRP13 for 4 weeks. (A) Representative CD68 (green) and SMA (red) immunofluorescence staining of the abdominal aortas from the indicated groups (n = 5). Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Representative western blot analysis of inflammatory markers (IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1) in abdominal aortas (n = 5). (C) Representative western blot analysis of apoptotic markers (Bax and Bcl-2) (n = 5). Cultured macrophages or HASMCs, pre-infected with Scr shRNA or NAMPT1 shRNA, were stimulated with Ang II or CTRP13 for 24 h. (D) Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 in macrophages (n = 5). (E) Representative TUNEL images and quantitative analysis of cultured HASMCs (n = 5). Scale bars, 100 μm. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test and are presented as means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05 versus Ang II+vehicle+Scr shRNA; #p < 0.05 versus Ang II+CTRP13 +Scr shRNA.

Discussion

In the present study, we used two distinct animal models of AAA and reported for the first time that CTRP13 could effectively reduce the incidence and severity of AAA in conjunction with decreased aortic proinflammatory cell infiltration, inflammation, and SMC apoptosis. Importantly, we have identified NAMPT1 as a new target of CTRP13 in the experimental AAA model. CTRP13 alleviated the degradation of NAMPT1 in a ubiquitination-dependent manner. In addition, we discovered that the blockade of NAMPT1 expression served as a novel mechanism that was responsible for increased vascular inflammation and SMC apoptosis, all of which were decreased in response to CTRP13 in AAA mice.

Increasing evidence has affirmed that CTRP13 is a potent endogenous metabolic and cardioprotective substance. It has been reported that CTRP13 improves glucose metabolism by activating the AMPK signaling pathway and alleviates lipid-induced insulin resistance in hepatocytes by inhibiting stress-activated protein kinase/JNK signaling.17 Recently, our research group demonstrated that CTRP13 has multiple protective effects against cardiovascular disease. In a Western-diet-fed atherosclerosis model, the plasma level of CTRP13 was obviously downregulated, and ectopic CTRP13 supplementation dramatically reduced the number of trapped macrophages, inflammatory reactions, and foam cell formation, thus slowing atherosclerotic progression.23 Under high-glucose conditions, CTRP13 infusion could improve endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) coupling and NO production to maintain endothelial function in mice and human patients.18 In addition, administration of recombinant CTRP13 could inhibit VSMC osteogenic differentiation and subsequent arterial calcification in chronic kidney disease.19 Interestingly, in the present study, we found that CTRP13 prevented the development of AAA induced by Ang II or CaCl2. Importantly, the suppression of aneurysm formation by CTRP13 was accompanied by a reduction in macrophage infiltration and inflammatory reactions and decreased vascular loss in the aorta. All of the aforementioned studies suggest multiple cell targets of CTRP13, but how CTRP13 works or whether there is a selective receptor in cells is still unclear.

This is the first study to demonstrate a novel protective effect of the CTRP family member CTRP13 against the formation and development of AAA. The CTRP family has pleiotropic roles in modulating the physiology and pathophysiology of metabolism and the immune system. CTRP1, CTRP3, and CTRP6 improve survival and restore cardiac function after myocardial infarction.24, 25, 26 The adipokine CTRP9 could not only attenuate adverse cardiac remodeling after acute myocardial infarction but also inhibit vascular proliferation and neointimal thickening,27,28 suggesting a key role of the CTRP family in the cardiovascular system. Further studies are required to investigate whether other members of the CTRP family are also involved in the regulation of AAA formation. Exploring a possible mixture of CTRPs may have important therapeutic value in the treatment of vascular dysfunction caused by multiple clinical diseases.

NAMPT1 is a classic enzyme that catalyzes NAD+ synthesis in salvage pathways.29 Accumulating evidence suggests that NAMPT1 deficiency is highly associated with various human diseases, including aging, atherosclerosis, acute lung injury, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, diabetes, and sepsis.30,31 However, the mechanism by which the expression and activity of NAMPT1 are regulated is still unknown. Zahra Bolandghamat Pour et al.32 reported that ectopic miR-154 expression inhibited the NAD salvage pathway by reducing the expression of NAMPT1 in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines to decrease cell viability and increase the rate of cell death, thus improving breast cancer outcomes. Hui Gao et al.33 found that miR-410 could influence NAMPT1 expression in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (hPAECs) and alleviate pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. In addition, Xiaoguang Sun et al.34 reported the presence of a mechanical stress-inducible region in the NAMPT1 promoter. Pharmacological promoter demethylation increased NAMPT1 promoter activity, whereas silencing the transcription factor STAT5 inhibited NAMPT1 transcriptional activity.34 However, in this study, we demonstrated that, in macrophages and VSMCs, NAMPT1 could be positively regulated by CTRP13 at the posttranscriptional level. CTRP13 could ameliorate the protein degradation of NAMPT1 by inhibiting Ub-dependent proteasomal degradation. Further experiments are still needed to explore the precise regulatory mechanism associated with NAMPT1 protein stability, which might provide more possible therapies for multiple human diseases.

Recently, NAMPT1 was reported to prevent the progression of thoracic aortic aneurysm by maintaining genomic integrity and inhibiting senescence in VSMCs.35 In this study, we demonstrated that NAMPT1 could mediate the effects of CTRP13 on the development of Ang II-induced AAA. NAD+, a biosynthetic metabolite generated by NAMPT1, is an essential dinucleotide that serves as a cofactor in multiple cellular events, such as nutrient metabolism. When NAD+ participates in signaling reactions, it acts as an enzyme substrate to regulate gene expression, mitochondrial function, and genome integrity.36 Tetsuo Horimatsu et al.37 found that nicotinamide, an NAD+ precursor, could potentially replenish aortic NAD+ levels and concomitantly enhance Sirt1 activity to inhibit AAA formation in AAA mouse models. Consistently, in our system, we discovered downregulation of aortic NAD+ levels in AAA, which was then efficiently reversed by CTRP13 supplementation, indicating that NAD+ depletion may lead to the pathogenesis of AAA. More interestingly, NAMPT1 silencing abrogated the beneficial effects of CTRP13 on Ang II-induced SMC apoptosis and macrophage inflammation. NAD-consuming proteins, including sirtuins, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), and CD38, may contribute to the regulatory effects of the NAMPT1-NAD axis in vascular repair.22 However, whether CTRP13-dependent NAD+ specifically acts on all of these NAD+-consuming enzymes to block AAA progression remains to be definitively established.

AAA is a chronic degenerative disease characterized by degeneration of vascular structure and dilatation of the aortic wall.8 Many experimental models have been developed for exploring the pathophysiology of AAAs and effective therapy. The most commonly used pharmacological models include periaortic calcium chloride application,38 intraluminal elastase,39 and systemic Ang II infusions.40 The aneurysm formation mechanisms associated with CaCl2 application are medial degeneration and macrophage infiltration.41 The intraluminal-elastase-induced AAA model is accompanied by fragmented elastic lamellae associated with leucocytes invading the media layer.42 Continuous infusion of Ang II into either LDL-receptor−/− or ApoE−/− mice leads to the formation of AAA. The Ang II model is the most frequently used model in mice. The characteristics of Ang II-induced AAA are associated with the activation of the inflammatory response and dramatic VSMC loss.43 Although each model has its limitations, the combination of different models, as in our study, will provide intriguing mechanistic insights into this human disease.

In summary, the present study provides evidence that treatment with CTRP13 prevents Ang II- and CaCl2-induced AAA formation in mice by upregulating NAMPT1 expression and its downstream effects, decreasing aortic proinflammatory cell infiltration, inflammation, and SMC apoptosis. These pleiotropic beneficial effects suggest therapeutic administration of CTRP13 as a viable strategy to limit AAA growth. The interplay between CTRP13 and abdominal aneurysm formation in humans remains an open question that requires further clinical research.

Materials and Methods

Patient Sample Collection

The clinical experiment was performed according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was supported by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Thirty-five AAA patients diagnosed by computed tomography angiography (CTA) at Union Hospital between 2016 and 2020 were enrolled. Nineteen healthy subjects who visited Union Hospital for a medical examination were recruited. None of the control subjects had a history of AAA or medication use (Table S1). Blood samples were obtained, and serum CTRP13 levels were measured with an ELISA kit (Aviscera Bioscience, CA, USA).

Mice

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The in vivo experiments were performed with 12-week-old male ApoE−/− mice (Ang II infusion model) and 12-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (CaCl2 model). Recombinant human CTRP13 protein (200 μg/kg; Aviscera Bioscience) or vehicle (normal saline) was injected intraperitoneally every other day for 4 weeks. Four weeks later, blood was collected from the abdominal vena cava before euthanasia and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min. Serum was collected and stored at −70°C until use (Tables S2 and S3).

The periadventitial tissue was dissected under an anatomical microscope. The suprarenal artery was identified as the passage between the last pair of intercostal arteries and the right renal branch. After dissection, the aorta was quickly measured, weighed, and stored for further research. The representative aorta was photographed for the whole aorta image. Body weights of all mice were measured at the end of the experiment. The ratio of aortic weight to body weight was calculated.

To quantify AAA incidence and size, the aortas were defined as areas of ≥50% dilation of the external diameter of the abdominal aorta compared with that of the normal abdominal aorta. The maximum width of the abdominal aorta was measured with Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics). AAA evaluation was performed by an investigator who was blinded to the experimental treatments. A second investigator was invited to confirm the aortic diameters and areas of mice in various treatment groups.

Ang II Infusion Model

Briefly, the mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (40 mg/kg) and then subcutaneously implanted with an osmotic minipump (ALZET, model 2004, 10389-18; Cupertino, CA, USA) in the midscapular area over the shoulder blade via a small incision. Ang II (Sigma, A9525) or vehicle (normal saline, 0.9% NaCl) was infused via the minipump at a rate of 1 μg/kg/min as previously described for 28 days.44

CaCl2 Application Model

After anesthesia, the abdominal aortic segment between the renal arteries and the bifurcation of the iliac arteries was isolated. The diameter of the aorta midway between the origin of the renal artery and the iliac artery bifurcation was measured in triplicate with video microscopy. Cotton gauze with 0.5 mol/L CaCl2 was applied to the external surface of the aorta for 15 min. The aorta was rinsed with 0.9% sterile saline, and the incision was closed. NaCl (0.9%) was used instead of CaCl2 in sham control mice.45

Injection of shRNA Lentivirus

Lentiviruses encoding Scr shRNA or NAMPT1 shRNA were synthesized by GeneChem (Shanghai, China). C57BL/6J and ApoE−/− mice were intravenously injected with Scr shRNA or NAMPT1 shRNA at a dose of 1 × 109 viral genome particles per animal using a 30G needle and an insulin syringe.

Systolic Blood Pressure Measurement

Systolic blood pressure was monitored in conscious mice every week by the use of a noninvasive tail-cuff system (BP-2000 System; Visitech Systems) as previously described.46

Histology

The abdominal aortas were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and embedded in paraffin. The specimens were cut into 6-μm sections and then subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Verhoeff-Van Gieson (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) staining in accordance with standard protocols.

Elastin fragmentation was graded according to the following criteria: grade 1, no elastin degradation; grade 2, mild elastin degradation; grade 3, severe elastin degradation; and grade 4, aortic rupture.

Immunofluorescence Analysis

The abdominal aorta sections were stained with antibodies against SMA (1:200; Abcam, ab7817) or CD68 (1:200; Bio-Rad, MCA1957). Images were acquired using an Olympus fluorescence microscope, and the related immunofluorescence densitometry data and relevant statistics were provided in Figure S5.47

Cell Culture

The RAW264.7 mouse macrophage cell line and HEK293T cell line were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 or DMEM. HASMCs were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and cultured in SMC medium (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with Smooth Muscle Cell Growth Supplement (SMCGS; ScienCell, catalog no. 1152). HASMCs at passages 3 to 6 were used for treatment with different agents.

To analyze inflammation in vitro, macrophages were divided into four groups—vehicle (normal saline), Ang II (10−7 M), CTRP13 (300 ng/mL), and Ang II (10−7 M) + CTRP13 (300 ng/mL)—and treated for 24 h. Prior to treatment, all cells were placed in serum-free medium for 24 h to maintain quiescence.

To analyze apoptosis in vitro, HASMCs were also divided into the vehicle (normal saline) group, Ang II-treated group (10−7 M), CTRP13 (300 ng/mL)-treated group, and Ang II (10−7 M) + CTRP13 (300 ng/mL) group and treated for 24 h. Prior to treatment, all cells were placed in serum-free medium for 24 h to maintain quiescence.

Mouse aortic SMCs were isolated from the aortas of mice via chemical digestion using type III porcine pancreatic elastase (250 μg/mL, Sigma) and type I collagenase (1 μg/mL; Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, USA).48

iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Analysis

iTRAQ analysis was performed by PTM Biolabs (Hangzhou, China) as previously described. Briefly, CTRP13- or vehicle-treated aorta extracts were used to prepare the peptide mixtures, which were then separated by a reversed-phase analytical column (Acclaim PepMap RSLC, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed with a Q Exactive mass spectrometer. The peptides were ionized by a nanoelectrospray ionization source and subjected to tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) coupled online to ultra-performance liquid chromatography analysis. Tandem mass spectra were identified using a mouse database. For protein quantification, the iTRAQ-8-plex setting was used in Mascot. The false discovery rate was adjusted to <1%, and the peptide ion score was set to ≥20.

TUNEL Assay

SMC apoptosis was measured by TUNEL staining according to the TUNEL TMR Red Kit (Roche Applied Science, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. After being washed for 30 min with PBS, the cells were incubated with permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-100) for 3 min. Apoptotic cells were labeled with 50 μL TUNEL reaction mixture per well for 60 min at 37°C. Cellular nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min at 37°C. Samples were washed with PBS and photographed under an Olympus fluorescence inverted microscope.

Western Blot Analysis

Mouse tissues or cell extracts containing equal amounts of total protein were resolved by 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE. Antibodies against IL-6 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 12912 and 12153), TNF-α (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology, 3707), MCP-1 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 39091 and 41987), NAMPT1 (1:1,000; Bethyl Laboratories, A300-372A), Bcl2 (1:1,000; Abcam, ab182858), Bax (1:1,000; Abcam, ab32503), hemagglutinin (HA) (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 3724), MYC (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 2276), and β-actin (1:2,000; Abcam, ab8226) were used as primary antibodies. After incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody, chemiluminescent signals were detected with Image Lab statistical software (Bio-Rad). The bands were quantified with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Protein expression was analyzed by ImageJ and normalized to β-actin expression. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times.49,50

Immunoprecipitation

Extracted cellular proteins were incubated with an anti-Myc antibody and rotated overnight at 4°C. Magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 88803) were added and incubated for another 4 h. The bead complexes were washed with lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitates were mixed with SDS loading buffer, boiled for 15 min, and then subjected to western blotting.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol Reagent (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). For mRNA quantification, 1 mg RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a Prime Script RT Reagent Kit (Takara), followed by quantitative real-time PCR with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System.

NAD+ Measurement

Freshly harvested aortas were isolated by removing the adventitial layer by dissection and denuding the endothelial layer by scraping. Mouse aortic medial NAD+ levels were measured by a colorimetric kit (BioVision Research Products, Mountain View, CA, USA) and are expressed relative to the total protein content.

NAMPT1 Enzymatic Activity

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates (7 × 105 cells per well) and treated as indicated. NAMPT1 enzymatic activity was determined with a commercial kit (AdipoGen Life Sciences, Liestal, Switzerland).51

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative results are expressed as the means ± SD of at least 3 independent experiments. Differences with a p <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t tests (two-tailed) or one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test when more than two treatments were compared. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for survival analysis. Fisher’s exact test was applied for comparisons of aneurysm incidence. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v.6.0 (GraphPad Software).

Author Contributions

W.X., Y.C., M.L., K.H. and C.W. researched data. C.W. and Y.C. analyzed and interpreted the data. C.W. and W.X. designed the study. M.L. and K.H. contributed to the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.W. and W.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript. C.W. is the guarantor of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81900268), the Major Key Technology Research Project of the Science and Technology Department in Hubei Province (2016ACA151), Key Projects of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (2016JCTD107), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016 YFA0101100).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.009.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Aggarwal S., Qamar A., Sharma V., Sharma A. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: A comprehensive review. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2011;16:11–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isselbacher E.M. Thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2005;111:816–828. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154569.08857.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umebayashi R., Uchida H.A., Wada J. Abdominal aortic aneurysm in aged population. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;10:3650–3651. doi: 10.18632/aging.101702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordon I.M., Hinchliffe R.J., Loftus I.M., Thompson M.M. Pathophysiology and epidemiology of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2011;8:92–102. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maegdefessel L., Spin J.M., Adam M., Raaz U., Toh R., Nakagami F., Tsao P.S. Micromanaging abdominal aortic aneurysms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:14374–14394. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormick M.L., Gavrila D., Weintraub N.L. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:461–469. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000257552.94483.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petsophonsakul P., Furmanik M., Forsythe R., Dweck M., Schurink G.W., Natour E., Reutelingsperger C., Jacobs M., Mees B., Schurgers L. Role of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Switching and Calcification in Aortic Aneurysm Formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019;39:1351–1368. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuivaniemi H., Ryer E.J., Elmore J.R., Tromp G. Understanding the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2015;13:975–987. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1074861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golledge J. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: update on pathogenesis and medical treatments. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019;16:225–242. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buck D.B., van Herwaarden J.A., Schermerhorn M.L., Moll F.L. Endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014;11:112–123. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng Y., Scherer P.E. Adipokines as novel biomarkers and regulators of the metabolic syndrome. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2010;1212:E1–E19. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Husseny M.W.A., Mamdouh M., Shaban S., Abushouk A.I., Zaki M.M.M., Ahmed O.M., Abdel-Daim M.M. Adipokines: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Vascular Dysfunction in Type II Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity. J. Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:8095926. doi: 10.1155/2017/8095926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida S., Fuster J.J., Walsh K. Adiponectin attenuates abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in hyperlipidemic mice. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.05.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeper N.J., Tedesco M.M., Kojima Y., Schultz G.M., Kundu R.K., Ashley E.A., Tsao P.S., Dalman R.L., Quertermous T. Apelin prevents aortic aneurysm formation by inhibiting macrophage inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;296:H1329–H1335. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01341.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tao M., Yu P., Nguyen B.T., Mizrahi B., Savion N., Kolodgie F.D., Virmani R., Hao S., Ozaki C.K., Schneiderman J. Locally applied leptin induces regional aortic wall degeneration preceding aneurysm formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:311–320. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seldin M.M., Tan S.Y., Wong G.W. Metabolic function of the CTRP family of hormones. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2014;15:111–123. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei Z., Peterson J.M., Wong G.W. Metabolic regulation by C1q/TNF-related protein-13 (CTRP13): activation OF AMP-activated protein kinase and suppression of fatty acid-induced JNK signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:15652–15665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang C., Chao Y., Xu W., Liang M., Deng S., Zhang D., Huang K. CTRP13 Preserves Endothelial Function by Targeting GTP Cyclohydrolase 1 in Diabetes. Diabetes. 2020;69:99–111. doi: 10.2337/db19-0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y., Wang W., Chao Y., Zhang F., Wang C. CTRP13 attenuates vascular calcification by regulating Runx2. FASEB J. 2019;33:9627–9637. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900293RRR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dale M.A., Ruhlman M.K., Baxter B.T. Inflammatory cell phenotypes in AAAs: their role and potential as targets for therapy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015;35:1746–1755. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai S. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt): a link between NAD biology, metabolism, and diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009;15:20–28. doi: 10.2174/138161209787185814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P., Li W.L., Liu J.M., Miao C.Y. NAMPT and NAMPT-controlled NAD Metabolism in Vascular Repair. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2016;67:474–481. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C., Xu W., Liang M., Huang D., Huang K. CTRP13 inhibits atherosclerosis via autophagy-lysosome-dependent degradation of CD36. FASEB J. 2019;33:2290–2300. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801267RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuasa D., Ohashi K., Shibata R., Mizutani N., Kataoka Y., Kambara T., Uemura Y., Matsuo K., Kanemura N., Hayakawa S. C1q/TNF-related protein-1 functions to protect against acute ischemic injury in the heart. FASEB J. 2016;30:1065–1075. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-279885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi W., Sun Y., Yuan Y., Lau W.B., Zheng Q., Wang X., Wang Y., Shang X., Gao E., Koch W.J., Ma X.L. C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-3, a newly identified adipokine, is a novel antiapoptotic, proangiogenic, and cardioprotective molecule in the ischemic mouse heart. Circulation. 2012;125:3159–3169. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.099937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lei H., Wu D., Wang J.Y., Li L., Zhang C.L., Feng H., Fu F.Y., Wu L.L. C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-6 attenuates post-infarct cardiac fibrosis by targeting RhoA/MRTF-A pathway and inhibiting myofibroblast differentiation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2015;110:35. doi: 10.1007/s00395-015-0492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan W., Guo Y., Tao L., Lau W.B., Gan L., Yan Z., Guo R., Gao E., Wong G.W., Koch W.L. C1q/Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Protein-9 Regulates the Fate of Implanted Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Mobilizes Their Protective Effects Against Ischemic Heart Injury via Multiple Novel Signaling Pathways. Circulation. 2017;136:2162–2177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uemura Y., Shibata R., Ohashi K., Enomoto T., Kambara T., Yamamoto T., Ogura Y., Yuasa D., Joki Y., Matsuo K. Adipose-derived factor CTRP9 attenuates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal formation. FASEB J. 2013;27:25–33. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Houtkooper R.H., Cantó C., Wanders R.J., Auwerx J. The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr. Rev. 2010;31:194–223. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L.Q., Heruth D.P., Ye S.Q. Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase in Human Diseases. J. Bioanal. Biomed. 2011;3:13–25. doi: 10.4172/1948-593X.1000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garten A., Petzold S., Körner A., Imai S.-I., Kiess W. Nampt: linking NAD biology, metabolism and cancer. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;20:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolandghamat Pour Z., Nourbakhsh M., Mousavizadeh K., Madjd Z., Ghorbanhosseini S.S., Abdolvahabi Z., Hesari Z., Ezzati Mobasser S. Suppression of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase expression by miR-154 reduces the viability of breast cancer cells and increases their susceptibility to doxorubicin. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1027. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao H., Chen J., Chen T., Wang Y., Song Y., Dong Y., Zhao S., Machado R.F. MicroRNA410 Inhibits Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling via Regulation of Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:9949. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46352-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun X., Elangovan V.R., Mapes B., Camp S.M., Sammani S., Saadat L., Ceco E., Ma S.F., Flores C., MacDougall M.S. The NAMPT promoter is regulated by mechanical stress, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, and acute respiratory distress syndrome-associated genetic variants. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014;51:660–667. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0117OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson A., Nong Z., Yin H., O’Neil C., Fox S., Balint B., Guo L., Leo O., Chu M.W.A., Gros R., Pickering J.G. Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase in Smooth Muscle Cells Maintains Genome Integrity, Resists Aortic Medial Degeneration, and Is Suppressed in Human Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Disease. Circ. Res. 2017;120:1889–1902. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cantó C., Menzies K.J., Auwerx J. NAD(+) Metabolism and the Control of Energy Homeostasis: A Balancing Act between Mitochondria and the Nucleus. Cell Metab. 2015;22:31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horimatsu T., Blomkalns A.L., Ogbi M., Moses M., Kim D., Patel S., Gilreath N., Reid L., Benson T.W., Pye J. Niacin protects against abdominal aortic aneurysm formation via GPR109A independent mechanisms: role of NAD+/nicotinamide. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz303. Published November 9, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiou A.C., Chiu B., Pearce W.H. Murine aortic aneurysm produced by periarterial application of calcium chloride. J. Surg. Res. 2001;99:371–376. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyake T., Aoki M., Osako M.K., Shimamura M., Nakagami H., Morishita R. Systemic administration of ribbon-type decoy oligodeoxynucleotide against nuclear factor kappaB and ets prevents abdominal aortic aneurysm in rat model. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:181–187. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X., Searle A.K., Hohmann J.D., Liu A.L., Abraham M.-K., Palasubramaniam J., Lim B., Yao Y., Wallert M., Yu E. Dual-Targeted Theranostic Delivery of miRs Arrests Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Development. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:1056–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lysgaard Poulsen J., Stubbe J., Lindholt J.S. Animal Models Used to Explore Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016;52:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka A., Hasegawa T., Chen Z., Okita Y., Okada K. A novel rat model of abdominal aortic aneurysm using a combination of intraluminal elastase infusion and extraluminal calcium chloride exposure. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009;50:1423–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daugherty A., Cassis L.A. Mouse models of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:429–434. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000118013.72016.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cassis L.A., Gupte M., Thayer S., Zhang X., Charnigo R., Howatt D.A., Rateri D.L., Daugherty A. ANG II infusion promotes abdominal aortic aneurysms independent of increased blood pressure in hypercholesterolemic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;296:H1660–H1665. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00028.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y., Krishna S., Golledge J. The calcium chloride-induced rodent model of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krege J.H., Hodgin J.B., Hagaman J.R., Smithies O. A noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system for measuring blood pressure in mice. Hypertension. 1995;25:1111–1115. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C., Xu W., An J., Liang M., Li Y., Zhang F., Tong Q., Huang K. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 accelerates vascular calcification by upregulating Runx2. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1203. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09174-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng W.L., She Z.G., Qin J.J., Guo J.H., Gong F.H., Zhang P., Fang C., Tian S., Zhu X.Y., Gong J. Interferon Regulatory Factor 4 Inhibits Neointima Formation by Engaging Krüppel-Like Factor 4 Signaling. Circulation. 2017;136:1412–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y., Wang C., Tian Y., Zhang F., Xu W., Li X. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 protects chronic alcoholic liver injury. The American Journal of Pathology. 2016;186:3117–3130. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang C., Xu W., Zhang Y., Huang D., Huang K. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated PXR is a critical regulator of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Cell Death & Disease. 2018;9:819. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0875-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sociali G., Grozio A., Caffa I., Schuster S., Becherini P., Damonte P., Sturla L., Fresia C., Passalacqua M., Mazzola F. SIRT6 deacetylase activity regulates NAMPT activity and NAD(P)(H) pools in cancer cells. FASEB J. 2019;33:3704–3717. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800321R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.