Abstract

The human transcription factor 4 gene (TCF4) encodes a helix–loop–helix transcription factor widely expressed throughout the body and during neural development. Mutations in TCF4 cause a devastating autism spectrum disorder known as Pitt–Hopkins syndrome, characterized by a range of aberrant phenotypes including severe intellectual disability, absence of speech, delayed cognitive and motor development, and dysmorphic features. Moreover, polymorphisms in TCF4 have been associated with schizophrenia and other psychiatric and neurological conditions. Details about how TCF4 genetic variants are linked to these diseases and the role of TCF4 during neural development are only now beginning to emerge. Here, we provide a comprehensive review of the functions of TCF4 and its protein products at both the cellular and organismic levels, as well as a description of pathophysiological mechanisms associated with this gene.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, Autism spectrum disorders, Schizophrenia

A primer on the human transcription factor 4

Transcription factor 4 (TCF4) is a member of the helix–loop–helix (HLH) family of proteins expressed in several cell types and tissues throughout the body1. Mutations in the TCF4 gene are known to cause the autistic condition known as Pitt–Hopkins syndrome (PTHS)2–4. Moreover, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified TCF4 polymorphisms linked with schizophrenia (SCZ) and other psychiatric conditions5–10, as well as non-neurological genetic diseases11–13. Importantly, TCF4 is abundantly expressed during neural development1,14,15, which likely reflects its relevance for the nervous system. In this review, we describe the known functions of TCF4 and the pathological consequences of TCF4 genetic variants linked to psychiatric disorders.

TCF4 is the gene’s official symbol (HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee), but it is also frequently referred to as E2-2, immunoglobulin transcription factor 2(ITF2), or SEF2-1. These different names stem from the distinct contexts in which the gene was originally described. E2-2 was the name given to a cDNA from a B-cell library, which encoded a protein—named ITF2—that interacted with enhancers in the immunoglobulin heavy and light chain loci16. An independent study purified two proteins from helper T-cell extracts and showed that they bind the murine leukemia virus SL3-3 enhancer; the proteins, named SL3-3 enhancer factor 2-1A and -1B (SEF2-1A/B), were later identified as ITF2 isoforms17. It is important to mention that TCF4 should not be confused with the immune regulator transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2), a member of the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors also referred to as T-cell factor 4 (TCF4), which therefore confusingly shares the same gene symbol.

TCF4 binds to DNA as either homo or heterodimers15,18–24, a phenomenon shown to increase HLH DNA–binding specificities and transcriptional control capacity25. The HLH family is characterized by the presence of a highly conserved dimerization domain formed by two amphipathic α-helices separated by a loop, hence the name “Helix–Loop–Helix”25. HLH transcription factors also carry a highly conserved group of basic residues at the N-terminus of the first helix, which is critical for DNA binding, being the reason why they are sometimes called basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) proteins25.

Association between TCF4 polymorphic variants and psychiatric diseases

GWAS identified TCF4 polymorphisms associated with SCZ5–7, bipolar disorder7,8, post-traumatic stress disorder10, and major depression disorder9. TCF4 polymorphisms have also been associated with the non-neurological diseases primary sclerosing cholangitis13 and Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD)11,12. Most TCF4 polymorphisms identified by GWAS were found in non-coding regions, and it is mostly unknown if and by which mechanisms these polymorphisms are causally linked with disease onset. An exception is FECD, for which the molecular pathology has been determined: most patients with FECD carry an expansion of the trinucleotide repeat (CTG)n in a TCF4 gene intron, leading to foci of condensed poly(CUG) RNAs complexed with splicing factor MBNL1 in the nucleus; sequestration of MBNL1 then results in erroneous splicing of its target mRNAs12,26,27.

Even though the causal relationship between TCF4 genetic variants and SCZ has not been demonstrated, certain polymorphisms are indeed associated with SCZ and have been studied regarding their correlation with the disease’s endophenotypes (see ref. 28 for an extensive review of aberrant phenotypes in patients with SCZ and their relationship with TCF4 polymorphisms). Different risk alleles have been associated with reduced sensorimotor gating as measured by pre-pulse inhibition29, modulation of sensory gating by smoking behavior as measured by P50 suppression of the auditory evoked potential29, poor verbal fluency performance30, and lower reasoning and problem-solving performance31. Curiously, some TCF4 risk variants in patients with SCZ have been associated with enhanced performance in word recognition32 and better performance in several attention-related tasks (but worse performance in unaffected individuals)33.

Experiments using neurons differentiated from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells showed that TCF4 expression was elevated in samples from patients with SCZ as compared to unaffected individuals34. Moreover, the association of increased TCF4 expression with SCZ is supported by Tcf4 overexpression in transgenic mice, which results in profound deficits in fear memory35 and sensorimotor gating36.

Interestingly, there are a few rare TCF4 coding variants detected in sporadic SCZ cases37,38, but most of them are localized outside known functional domains. The exceptions are a F211L variant located in an activation domain (AD3) and a P156T variant located in a nuclear localization signal (NLS-1) domain37,38. It seems that the coding variants in sporadic SCZ lead to higher activity-dependent TCF4-mediated transcription when compared to the wild-type variants, in reporter assays conducted with rat primary neurons39. However, such effect is marginal, suggesting that any possible impact of SCZ coding variants on TCF4 function would be modest.

Monogenic determination of Pitt–Hopkins syndrome by TCF4 mutations

In 2007, three studies independently identified mutations in TCF4 as the genetic cause of PTHS2–4. Until 2016, around 300 PTHS cases had been confirmed around the world40, although detailed molecular data on the types of TCF4 mutations carried by these patients were retrieved for approximately 150 individuals only41. Irrespective of the numbers reported in the literature, the total case count is certainly higher by now, not only because the disease is caused by de novo mutations, which are expected to arise at a steady rate, but also because some cases are simply not diagnosed or reported, especially in developing countries. PTHS is expected to be equally prevalent worldwide and one study estimated that the prevalence of PTHS caused by chromosomal deletions is 1/34,000–1/41,00042. In contrast, the First International Consensus Statement on Diagnosis and Management in PTHS estimated the prevalence as 1/225,000–1/300,000 based on individuals with PTHS in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands41.

In recent years, compiled data better delineated the disease’s phenotype and natural history, and helped create clinical diagnosis and treatment protocols40,41,43–46. It is now clear that the PTHS phenotypes are highly variable among individuals, but some aberrant phenotypes are found in most patients, including a very peculiar set of dysmorphic facial features combined with intellectual disability, which led Drs David Pitt and Ian Hopkins to first recognize it as a separate medical entity47. The characteristic PTHS facial gestalt is present in approximately 89% of patients, consisting of a broad beak-shaped nose with flaring nostrils, wide mouth with a bow-shaped protruding upper lip and fleshy lower lip, spaced teeth, ears with thick helices, bitemporal narrowing, enophthalmia, thin eyebrows in the lateral portion, and full cheeks. As individuals age, facial features become more obvious and prognathism may appear. A certain percentage of individuals also display other dysmorphic features, such as single transverse palmar crease (60% of cases), digit anomalies (53%), such as syndactyly or polydactyly, persistent fetal pads (45%), short stature (38%), urogenital malformations (32%), scoliosis (20%), as well as a tendency to exhibit smaller-than-normal head circumference (~59% of cases)40,41,43–46.

All individuals with PTHS have intellectual disability and disturbed sensorimotor gating, speech delay, mild-to-severe motor delay, as well as generalized hypotonia. About 78% of patients frequently engage in stereotypical and intense repetitive movements or behaviors, which put individuals with PTHS within the autistic spectrum if considered in combination with deficits in communication and social interaction beyond what would be expected for individuals with low cognitive levels, motor and speech delay48.

Approximately half of patients with PTHS display abnormal breathing patterns, which start on average at 6 years of age and typically consist of tachypnea followed by apnea that lasts for a few minutes, occurring from several times in 1 hour to a few times in 1 year40,41,43–46. Periods of tachypnea and apnea may occur independently or be induced by arousal, stress, or anxiety, and periods of apnea may be followed by cyanosis41.

About a third of all patients develop epileptic seizures, which may start in the first year of life or even in early adulthood. In a few individuals, abnormal breathing precedes seizures, but the former is not due to epileptic activity, because EEG may be normal in children with respiratory anomalies. Furthermore, some brain abnormalities have been identified by magnetic resonance imaging, such as small or absent corpus callosum, large ventricles, and abnormally shaped posterior cranial fossa40,41,43–45.

Gastroenterological manifestations are common in individuals with PTHS and include constipation (70% of cases), reflux (35%), and eructation (29%). Other functional deficits are myopia (52%), hyperopia (22%), strabismus (44%), nystagmus (14%), sleep disturbances (18%), and deafness (10%)40,41,43–46. Respiratory and urinary tract infections occur in one third of individuals, mainly during childhood. Notably, immunological changes—represented by low levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM—have been sporadically reported, but their relationship with recurrence of infections is still uncertain41.

Transcription factor 4: an elusive molecular player

HLH proteins are grouped into different classes based on the types of dimers they form, patterns of expression, and specificity of DNA binding25. TCF4 is a member of the class I HLH group (also named E-proteins)49, because it is widely expressed and binds as homo or heterodimers to the consensus sequence CANNTG (“Ephrussi box” or E-box)24.

TCF4 protein domains

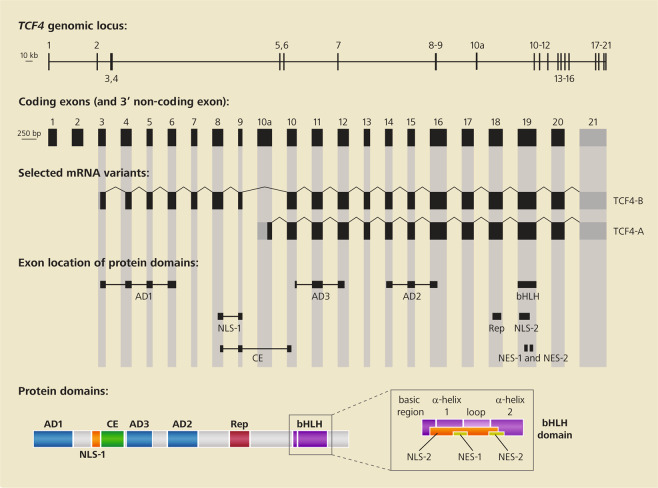

Besides the C-terminal HLH domain responsible for dimerization and DNA binding, TCF4 and other E-proteins have N-terminal domains responsible for transcriptional regulation. Full length E-proteins usually contain three conserved activation domains (AD1, AD2, and AD3; Fig. 1) that are able to modulate transcription and, depending on cell type, can independently or cooperatively regulate expression of target genes50–55. AD1 is able to bind transcriptional co-activators p300/CBP and STAGA, as well as co-repressor ETO, through the PCET motif (p300/CBP and ETO Target)53,54,56–60. AD2 also binds to p300/CBP53,55, but there is no evidence that it can recruit ETO or any other transcriptional co-repressor. Transcriptional co-activators p300/CBP and STAGA remodel chromatin through their intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity and recruitment of basal transcriptional machinery. Transcriptional co-repressor ETO, on the other hand, promotes DNA condensation through recruitment of histone deacetylases. Therefore, p300/CBP, STAGA, and ETO compete for binding to AD1 and, as a consequence, TCF4 may either activate or repress target genes. The third activation domain, AD3, is located between AD1 and AD2 (Fig. 1) and has been shown to directly interact with the TAF4 subunit of general transcription factor II D, part of the basic transcriptional machinery, enhancing the formation of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex at target genes61. Despite data obtained from deletion studies62, it remains to be further explored how AD3 participates in the transcriptional regulation exerted by TCF4, particularly in the nervous system.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the TCF4 genomic locus.

The genomic locus is located on chromosome 18 (top line; exon sizes and distances between exons shown to scale), coding exons (middle lines; exon sizes, but not distances, shown to scale), and TCF4 protein domain structure (bottom line; domain sizes not to scale). The last exon on the right, displayed in gray, is non-coding. Only transcript variants coding for isoforms TCF4-B and TCF4-A are shown, which are transcribed from alternative promoters starting at exons 3 and 10, respectively. AD activation domain, NLS nuclear localization signal, NES nuclear export signal, bHLH basic helix–loop–helix DNA-binding domain, CE conserved element, Rep repression domain. In the bottom line, the protein motifs inside the bHLH domain are shown in detail in the enlarged inset. Based on refs. 22,61.

E-proteins also contain two intramolecular regulatory domains. The first, termed “conserved element” (CE), is located between AD1 and AD3 (Fig. 1) and is able to repress AD1 activity63. The second, termed “repression domain” (Rep), falls between AD2 and HLH (Fig. 1) and was shown to repress the activity of both AD1 and AD264. CE and Rep intramolecular regulatory domains probably act by preventing the recruitment of transcriptional co-factors. Therefore, intramolecular regulatory events repress AD1-mediated transcriptional activation or repression if the genomic context is inclined to either recruitment of transcriptional co-activators or co-repressors, respectively.

Another possible mode of intramolecular regulation seems to occur in TCF4 through a 4-residue sequence—Arg-Ser-Arg-Ser (RSRS)—located between the Rep and HLH domains. Its presence decreases transcriptional activity65, but such effect is not observed in all cell types22.

Besides having domains directly involved in transcriptional regulation, mammalian E-proteins contain conserved NLSs (NLS-1 and NLS-2; Fig. 1) and nuclear export signals (NES-1 and NES-2; Fig. 1). NLS-1 overlaps with the CE domain at the N-terminal region and NLS-2 overlaps with NES-1 and NES-2 in the HLH domain at the C-terminal region66. Further work is required to understand how these domains interact with each other and with other proteins to regulate TCF4 activity in vivo.

TCF4 gene structure and transcript diversity

The human TCF4 gene is located on chromosome 18, spanning approximately 442 kb in chromosomal region 18q21.2, harboring 41 exons, of which 20 are alternative 5’ exons, 20 are internal coding exons, and 1 is the 3’ terminal non-coding exon. Alternative transcription start sites, which are found upstream of internal exons 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10, are responsible for the generation of at least 18 N-terminally distinct protein isoforms, termed TCF4-A through TCF4-R (summarized in Fig. 1)22. It should be noted that transcript diversity is even higher, due to alternative splicing of internal exons.

Because of TCF4’s structure and regulation, different isoforms may or may not contain AD1, NLS-1, CE, or RSRS sequences. As AD1 is encoded in exons 3–6 (Fig. 1), with the PCET motif coded for only by exon 3, the longer isoforms (TCF4-B, J, K, and L) are the only ones containing a complete AD1 domain with the PCET motif. Other isoforms, such as TCF4-C, contain only parts of AD1 or lack it entirely22. Furthermore, as NLS-1 and CE are encoded in exons 8–9 and 8–10, respectively, splicing out the cassette exons 8 and 9 generates “Δ isoforms,” different from their “complete” cognates by the lack of NLS-1 and CE. Moreover, the presence of two alternative donor splice sites in exon 18 allows the inclusion or exclusion of a 12-nucleotide segment encoding the RSRS sequence, present in positive (+) isoforms but absent in negative (–) isoforms. As all TCF4 transcripts have exons 10–20, all isoforms contain AD3 (exons 10–12), AD2 (exons 14–16), Rep (exon 18), and HLH, NLS-2, NES-1, and NES-2 (exon 19)22.

Spatial pattern of TCF4 expression

TCF4 spatial pattern of expression is often described as ubiquitous, being detected in multiple organs throughout development22,67. However, some TCF4 transcripts are only detected in a few tissues, while others are widely expressed (see ref. 22 for a detailed description of patterns of expression for each transcript). Moreover, expression levels vary between tissues, as certain TCF4 transcripts may be more or less abundant than others in a particular tissue22,67. Curiously, TCF4 transcripts encoding (+) and (–) isoforms are equally abundant, whereas transcripts encoding Δ isoforms are less abundant than those encoding the complete cognate isoforms. Detailed RT-PCR analysis of the expression of a wide range of different TCF4 transcripts revealed that, although a stark majority of transcripts display expression in the brain, those coding for five isoforms (TCF4-J, TCF4-K, TCF4-L, TCF4-M, and TCF4-N) are predominantly expressed in the testis and absent in the brain22.

Spectrum of TCF4 mutations in patients with Pitt–Hopkins syndrome

TCF4 genetic variants carried by children with PTHS

The list of TCF4 mutations found in the hundreds of patients with PTHS described so far include missense (~15% of cases), nonsense (~15%), and splice-site (~10%) point mutations, as well as small insertions or deletions (indels) resulting in frameshift (~30%), and translocations and large deletions encompassing TCF4 partially or entirely (~30%)23,41,43–46.

Depending on the location and type of mutation, the TCF4 gene and its protein products are differently affected. Most TCF4 missense mutations in PTHS are located in exon 19, which encodes the HLH domain, but there are cases where the missense mutation is in exons 15 or 18, which encode part of AD2 and Rep, respectively23. Importantly, these mutations affect all isoforms. Most nonsense and frameshift mutations and all splice-site mutations affect all isoforms, but there are cases where nonsense and frameshift mutations are located in exons 8–9 and upstream of exons 10a–c, sparing the Δ and the shorter isoforms, respectively23. Some translocations and deletions encompass only initial exons (1 through 4) or intermediate exons (5 through 9), sparing intermediate and shorter isoforms, respectively23.

The impact of the structural diversity and expression dynamics of TCF4 on physiology remains a mystery, but some have suggested that the different types of mutation in individuals with PTHS could affect the encoded protein differently and therefore underlie the phenotypic variability observed among patients68. Bedeschi et al.68 raised the possibility of classifying patients with TCF4 mutations into three groups: (I) non-syndromic patients with mild intellectual disability or syndromic patients with mild intellectual disability but presenting only a few of the PTHS dysmorphic features; (II) syndromic patients with mild-to-severe intellectual disability but without seizures and with milder facial features; and (III) syndromic patients with severe intellectual disability presenting the characteristic PTHS facial gestalt. The authors hypothesized that such classification correlates with TCF4 isoforms affected by the mutations carried by the patients, as individuals in groups I, II, and III usually carry mutations that affect only AD1 (present in the longer isoforms), only NLS-1/CE (present in the longer and intermediate isoforms, but not in their Δ cognates), or AD2/Rep/HLH domains (present in all isoforms), respectively68.

Interestingly, in 2016, two different cases were reported of family members with mild intellectual disability carrying a hereditary TCF4 mutation69,70. Both cases strongly support the genotype/phenotype paradigm, showing that certain TCF4 mutations result in mild pathophysiology, not incompatible with reproduction. On the other hand, there are a few described cases of mild PTHS phenotype where a frameshift mutation located in exon 20 elongates the coding region to the terminal non-coding exon 21, not directly affecting any known domains but affecting all isoforms71–73. One hypothesis to explain these observations is that the mild phenotype observed in these patients is due to the disruption of dimer stability and/or function by the elongated TCF4 isoform, in a manner that depends on dimerization partners and/or genomic context. An alternative explanation is that the frameshift mutation leads to protein degradation. In support of this hypothesis, another frameshift mutation, S653Lfs*57, has been shown to lead to TCF4 degradation, aggregation, and subsequent impaired DNA binding to the E-box23.

Molecular pathology in PTHS: TCF4 haploinsufficiency or dominant-negative effect?

Most TCF4 mutations carried by patients with PTHS result in an obvious haploinsufficiency state, as translocations, deletions, or nonsense and frameshift mutations limit the production of certain or all isoforms to only one allele23. On the other hand, the resulting effect of missense mutations is less obvious. One possibility is that missense mutations in the basic region of the HLH domain impair or abolish TCF4 DNA binding. Alternatively, missense mutations elsewhere in the HLH domain may affect TCF4 dimerization, resulting in unstable or absent HLH dimers involving TCF423,24. In addition, missense mutations affecting AD2 and Rep may disturb the function of these domains or perturb TCF4 dimer stability depending on dimerization partner23. For all these possibilities, the net functional result could be considered hypomorphic or loss-of-function.

The fact that some missense mutations perturb or abolish TCF4-mediated transcriptional regulation without affecting dimerization ability in vitro23 suggests that the aberrant TCF4 protein may sequester its molecular partners, resulting in a hypomorphic or dominant-negative effect. However, it is reasonable to speculate that a hypomorphic or dominant-negative effect would be very mild or not happen in vivo due to the diminished stability of dimers with a mutant TCF424. Indeed, there is some evidence indicating that the half-life of HLH proteins relies to some extent on dimerization, as protein degradation can be prevented by dimer stabilization in the nucleus through DNA binding and interaction with transcriptional co-factors58,74.

If some missense mutations result in a significant hypomorphic or dominant-negative effect rather than a haploinsufficiency state in vivo should be further investigated. However, there is no doubt that PTHS results from loss of TCF4-mediated transcriptional regulation. How such dysregulation triggers PTHS pathophysiology is still unclear, but it seems to involve the general role of E-proteins as cell-cycle regulators and the specific role of TCF4 in cellular differentiation—a topic explored in the following section.

TCF4 function

Transcriptional regulation by TCF4

The binding of HLH dimers containing E-proteins to specific promoters and/or enhancers depends on the composition of the dimer itself and on E-box internal and flanking DNA sequences, as each dimer member has higher affinity for E-boxes flanked by particular sequences75–77. Furthermore, affinity of one dimer for a promoter and/or enhancer may depend on homotypic cooperativeness with preexisting dimers or collective binding with transcriptional co-factors78. Finally, E-protein DNA-binding specificity is regulated by Ca2+-dependent proteins such as calmodulin and S100, which interact directly with the basic region of the HLH domain79,80. In the presence of Ca2+, calmodulin exhibits low affinity for HLH heterodimers, preferentially inhibiting the DNA binding activity of E-protein homodimers. Indeed, cellular manipulation of calmodulin or Ca2+ levels has a direct effect on E-protein–mediated transcription81.

E-protein function is usually understood under the paradigm that tissue-specific class II HLH proteins dimerize with the widely expressed E-proteins to regulate specific gene networks that determine lineage commitment and cellular differentiation82,83. Particularly, TCF4 has been associated with the regulation of hematopoiesis84, myogenesis85, neurogenesis86, melanogenesis87, and osteogenesis88, as well as the differentiation of endothelial89, mammary gland90, placental91, and Sertoli cells67.

Differentiation programs activated by HLH proteins are usually coordinated with cell-cycle exit through E-protein–mediated transcriptional activation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs)92,93. Class V HLH proteins act in opposition to this process; these proteins, called inhibitors of DNA binding (ID), indirectly promote cell cycle through inhibition of E-proteins and, consequently, inhibition of CDKI expression83,94. Therefore, cycle withdrawal or promotion may rely on the stoichiometric excess of either ID or E-proteins in order to favor the prevalence of bHLH/ID or bHLH/bHLH dimers, respectively, but the regulation of the equilibrium between E-protein and ID protein levels is not completely understood and possibly varies according to cell type.

Considering the dynamics of E-protein dimer affinity for distinct E-box sequences, discovering TCF4 target genes is not trivial. Initially, putative targets were uncovered by demonstrating that TCF4 interacted with promoter/enhancer sequences of particular candidate genes (via cDNA library screening or DNA-binding competition assays)—such as the immunoglobulin heavy and light chain enhancers16 and promoters of genes encoding thyroglobulin95, tyrosine hydroxylase96, somatostatin receptor II97,98, fibroblast growth factor 165, and Purkinje cell protein 299. In addition, TCF4-mediated regulation was investigated using luciferase reporter assays, exemplified by the study of promoters for CDKIs92, and NRXN1β and CNTNAP224. Interestingly, NRXN1β and CNTNAP2 have been shown to cause PTHS-like autosomal recessive intellectual disability disorders100, both of which manifest motor and speech delay, stereotypical and intense repetitive movements, and tachypnea and/or apnea, but without the PTHS characteristic facial gestalt. Finally, it should be noted that the molecular approaches described above did not provide a full understanding of TCF4-mediated transcriptional regulation because most experiments were conducted with exogenous transgenes and reporter cassettes and did not take into account activity of the endogenous TCF4 locus.

Although microarray and next-generation RNA sequencing experiments alone cannot directly indicate TCF4 target genes, they can reveal a large-scale picture of the gene networks influenced by TCF4. For example, microarray analysis after TCF4 knockdown in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y revealed differentially expressed genes mostly involved in cell survival, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and neuronal differentiation101.

Moreover, RT-qPCR with mRNA enriched via purification of translating ribosomes from neurons of the rat medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) revealed that, relative to the majority of known ion channel genes in the rat genome, KCNQ1 and SCN10a are substantially overexpressed after TCF4 knockdown102. Other studies used a combination of omics approaches in human neuronal cell lines to reveal that several TCF4 target pathways are involved in cell survival, cell-cycle regulation, neurogenesis, and neuronal lineage commitment103–106, although evidence of direct TCF4 target genes obtained through credible CHIP-Seq experiments in different cell types is still missing.

Roles of TCF4 during neural progenitor cell maintenance and differentiation

Despite some limitations, the studies described above point to a critical role of TCF4 in nervous system physiology and development. TCF4 expression in the brain increases considerably at the end of prenatal life and decreases at early infancy to basal levels that persist through adulthood107. TCF4 is expressed in cortical and subcortical regions of the developing and adult brain, prominently in the cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamic and amygdaloid nuclei, a pattern that is highly similar between humans and rodents1,102,108.

It is well known that HLH proteins exert critical roles during neural progenitor cell (NPC) maintenance and/or differentiation into neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes109. Repressor HLH proteins such as HES and ID regulate NPC auto-renovation, ensuring maintenance of the population and formation of an appropriate number of neurons and glia throughout development109. During the neurogenic phase, proneural HLH proteins coordinate not only a generic neuronal identity but also specific neuronal subtypes. Generally, NEUROG1 and NEUROG2 expression is restricted to the dorsal telencephalon, which originates glutamatergic neurons, and ASCL1 is predominantly expressed in the ventral telencephalon, which originates GABAergic neurons109. During the gliogenic phase, OLIG1 and OLIG2 expression regulates NPC differentiation into oligodendrocytes, and further HES and ID expression regulates NPC differentiation into astrocytes109. There is evidence that TCF4 is able to dimerize with these HLH proteins15,18–24, but results showing that TCF4 dimers regulate neurogenic and gliogenic processes during brain development are still lacking.

TCF4 has high affinity for Mediator—a multiprotein complex that regulates transcription by connecting enhancers to promoters110. In NPCs, TCF4 recruits Mediator to define most super-enhancers—regions of high-density Mediator binding responsible for maintaining cell identity and viability through regulation of lineage-specific and cell-cycle genes110. Many such genes regulated by TCF4 encode neurogenic HLH and other proteins that interact and colocalize with TCF4 at super-enhancers, including in the TCF4 gene itself21,110. Indeed, TCF4 seems to regulate its own expression in NPCs, as TCF4, Mediator and epigenetic marks that promote gene expression are found near transcriptional start sites for TCF4’s shorter isoforms110. This suggests that a positive feedback loop maintains expression of those transcription factors, resulting in maintenance of the NPC population.

TCF4 levels increase considerably during neurogenesis, and differentiation is promoted by a combination of factors that induce the expression of TCF4 longer isoforms, mainly TCF4-B, through the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway and imprinted transcription factor ZAC1104,111.

Role of TCF4 during cortical development

In mice, TCF3—another E-protein—acts by regulating the expression of TCF4-B at early stages of neurogenesis in the mouse dorsal telencephalon, specifically at embryonic day 12 (E12), as either Tcf3 or Tcf4 loss-of-function results in an increased population of intermediate progenitors in the ventricular and subventricular zones112. However, even though TCF3 does not influence TCF4 levels at later stages of neurogenesis, both factors continue to influence the differentiation in a global manner, as Tcf3 or Tcf4 gain- or loss-of-function results in decrease or increase in the population of mouse radial glia cells at postnatal day 2 (P2), respectively86. Therefore, TCF4 regulates both NPC maintenance and neurogenesis during mouse telencephalon development. It is possible that regulation of Tcf4 expression is context-dependent, with different pathways acting in different regions of the developing telencephalon, but such possibility still needs to be further investigated.

Importantly, Tcf4 loss-of-function in mice is accompanied by deficits in cortex development and cortical layer structure: Tcf4−/− mice display aberrant numbers of different sub-types of cortical neurons, including those expressing SATB2 and BRN2 markers, but these alterations are surprisingly milder in Tcf4+/− animals112.

Besides regulating NPC maintenance and neurogenesis, TCF4 also acts in neuronal migration and neurite formation during telencephalon development. Tcf4+/− mice show an increased number of neurons “stuck” in deeper layers of the telencephalon instead of migrating to the cortical plate112. Also, Tcf4 knockdown in the mouse telencephalon at E14.5 increases the number of neurons “stuck” in the ventricular and intermediate zones113. Curiously, knockdown of Bmp7—a gene negatively regulated by TCF4 that codes for a TGF-β receptor ligand—partially rescues normal neuronal migration in these mice. Tcf4 knockdown in the developing mouse telencephalon also disturbs the formation of the neuronal leading process, which could explain the disruption in neuronal migration113.

Conversely, increasing levels of TCF4-B in the developing rodent telencephalon increases the rate of neuronal migration112 and results in aggregation of pyramidal neurons in the mPFC but not in other areas of the neocortex114, a finding that may be of significance in the context of trying to understand the causality between TCF4 polymorphisms and SCZ. Such abnormal aggregation was associated with neuronal activity mediated by Ca2+ influx as a result of NMDA receptor activation, and normal distribution of pyramidal neurons could be rescued by increasing levels of calmodulin, thereby inhibiting TCF4-mediated transcriptional activity114. Measures of cellular electrophysiology and spontaneous Ca2+ transients revealed that TCF4-B gain-of-function increases neuronal excitability, indicating that TCF4-mediated transcription regulates spontaneous neuronal activity in the developing neocortex and potentially increases NMDA receptor function114.

Role of TCF4 beyond cortical development

Recently, Wang et al. investigated the potential roles of TCF4 during mouse hippocampus development108. Conditional knockout of Tcf4 in NPCs of the dentate neuroepithelium resulted in a drastically reduced hippocampus that persisted through adulthood. Particularly, the size of the dentate gyrus was dramatically reduced. During dentate gyrus development, radially migrating NPCs form a migratory stream from the neuroepithelium toward the hilus of the dentate gyrus, where they undergo reorganization to build the neurogenic subgranular zone115. Tcf4 knockout disturbed NPC migration, as these cells were “stuck” in the dentate migratory stream at P0 instead of migrating to the hilus, thus disrupting subgranular zone formation108. Interestingly, the disturbance in migration is due to disorganized radial glia scaffold from the neuroepithelium along the dentate migratory stream and to reduced expression of Wnt7b108—a TCF4 target known to be responsible for neurite development through the noncanonical Wnt pathway. Not surprisingly, such migration defects lead to altered social behavior and memory performance in adult mice108.

Furthermore, it has been recently shown that Tcf4−/− mice exhibit corpus callosum and anterior commissure malformation, which are detected at E17.5 and persist up to P0116. It is noteworthy, however, that heterozygous animals seem to be unaffected. Since the formation of midline glial structures is essential for commissural formation117, the authors suggest that loss of midline glia may be responsible for the observed defects in Tcf4−/− mice.

The role of TCF4 in the developing brain is not restricted to the telencephalon. TCF4 dimerization with ATOH1 is critical for normal pontine nuclei development. Tcf4−/− mice and double-heterozygote Tcf4+/−/Atoh1+/− mice show extensively reduced pontine nuclei due to abnormal migration of neurons in the dorsolateral rhombencephalon118. Curiously, such abnormal migration is restricted to pontine nuclei, even though Tcf4 and Atoh1 are both expressed throughout the rhombic lip.

Altogether, these findings suggest that TCF4 has specialized roles in different populations of NPCs throughout the developing brain.

Role of TCF4 in post-mitotic neuronal function

TCF4 function also seems to be intimately associated with neuronal activity. In rat primary neurons, transcription mediated by any TCF4 isoform is dependent on depolarization39. Synaptic activity triggers Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors and type L voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, thereby activating protein kinase A, which then phosphorylates TCF4 at serine residues 448 and 464 (between AD2 and Rep). Such phosphorylation is necessary for transcriptional activity, as mutations affecting these sites are sufficient to prevent the abnormal distribution of pyramidal neurons in the rat mPFC resulting from TCF4-B gain-of-function39. Furthermore, Tcf4 knockdown in neurons of the rat mPFC at E16 attenuates neuronal excitability by increasing the expression of the Kcnq1 and Scn10a genes, both of which code for ion channels mostly expressed in the peripheral nervous system and responsible for regulating action potential firing rate102. In addition, Tcf4 knockdown in post-mitotic interneurons of the adult mouse olfactory bulb increases dendrite number and length; conversely, Tcf4 overexpression decreases dendrite number and length119.

Role of TCF4 in other neural cell types

The studies listed in the preceding sections made it clear that TCF4 function is associated with neuronal activity and regulation of different aspects of neural development. However, Phan et al.120 recently demonstrated that TCF4 function is also associated with oligodendrocyte development and myelination. By assessing molecular convergence across five independent mouse models of PTHS with distinct heterozygous mutations, the authors found upregulation of genes associated with neuronal function and downregulation of genes associated with oligodendrocytes and myelination in neonate and adult transcriptomes from several brain regions. They observed decreased numbers of mature oligodendrocytes and more oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, decreased proportion of myelinated axons in the corpus callosum, and increased proportion of neuronal activity being transmitted down unmyelinated axons in Tcf4+/− mice120. In order to rule out the possibility that Tcf4 mutations affect oligodendrocytes in a non–cell-autonomous manner, the authors induced differentiation of cultured primary oligodendrocyte progenitor cells dissociated and purified from neonatal mice, as well as deleted a single Tcf4 allele in the oligodendrocyte lineage by crossing Olig2-Cre+/− mice with “floxed” Tcf4fl/+ mice. Both approaches revealed increased proportion of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells and reduced proportion of mature oligodendrocytes as a result of the Tcf4 mutation120, thus confirming that TCF4 regulates oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation and/or survival in a cell-autonomous manner.

In addition, Wedel et al.121 recently showed that TCF4 is required for terminal differentiation in the oligodendrocyte lineage. In genetically modified prenatal mice without Tcf4 transcripts encoding longer isoforms, the authors found that oligodendroglial cells are arrested in the pre-myelinating stage. Furthermore, they observed severely delayed myelination in ex vivo organotypic slice cultures, showing that such effect is cell-autonomous. Notably, TCF4 was shown to genetically interact with OLIG2 for terminal oligodendrocyte differentiation121: double-heterozygote Tcf4+/−/Olig2+/− mice exhibited significant reduction in the number of differentiating oligodendrocytes at E18.5. Such findings suggest that part of the functional deficits in patients with PTHS may be caused by altered oligodendrocyte function and myelination.

Current knowledge on aberrant functions of TCF4 in disease

It is noteworthy that several Tcf4+/− mouse models, carrying distinct types of Tcf4 mutation in heterozygosity, exhibit mildly aberrant phenotypes, including subtle changes in cerebral cortex cellular composition112, hippocampus development108,116, and electrophysiological properties of neurons122. It is unclear whether such set of abnormalities in heterozygous mice closely resembles the phenotypes found in children with PTHS carrying similar TCF4 mutations. An alternative interpretation is that the mild phenotypes observed in Tcf4+/− mice do not correspond to human phenotypes and that these dissimilarities result from differences between rodent and human brain composition and development, which are substantial and should not be ignored.

Nevertheless, some Tcf4+/− mice harbor clinically relevant genetic variants, such as missense mutations affecting the arginine residues of the basic region of the HLH domain or deletions in exon 19, which codes for the HLH domain122,123. Assessment of behavior and electrophysiology in these Tcf4+/− mice showed that they can partially model the PTHS phenotype. Notably, Kennedy et al.123 first reported that Tcf4+/− mice (harboring a deleted exon 19) exhibit alterations in balance and motor coordination, preference for social isolation over interaction, and repetitive behaviors represented by increased grooming. These mice also show dysregulation in sensorimotor gating, as adults are hyper-responsive and have significant deficits in prepulse inhibition123. Curiously, communication deficits were also observed in the form of significantly reduced ultrasonic vocalizations and weaker ultrasonic distress calls in Tcf4+/− pups.

Multiple Tcf4+/− mouse models present hippocampus-dependent cognitive deficits, which were assessed through behavioral tasks of spatial and associative learning and memory122,123. Interestingly, such deficits were shown to be coupled with enhanced hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) at Schaffer collaterals between CA3 and CA1, which is seemingly driven by NMDA receptor hyperfunction. In addition, next-generation sequencing experiments were performed on hippocampal CA1 tissue from wild-type and Tcf4+/− mice123 and the authors found significant dysregulation in pathways associated with neuronal plasticity, axon guidance, memory-associated genes, as well as significant demethylation in upregulated genes associated with these pathways.

Considering the role of TCF4 in the regulation of histone acetylation states through the activity of either AD1 and/or AD2, Kennedy et al. also assayed whether histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition would be sufficient to normalize the enhanced hippocampal LTP phenotype of Tcf4+/− mice123. Surprisingly, treatment with the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A significantly reduced LTP in the Tcf4+/− mouse hippocampus. Moreover, Hdac2 knockdown and subchronic treatment with HDAC inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) were sufficient to improve learning and memory in Tcf4+/− mice, thus indicating that cognition in PTHS model mice can be improved by HDAC inhibitors through normalization of synaptic plasticity.

Concluding remarks

It is now clear that Tcf4+/– mice display some aberrant behaviors, which may reflect the pathological findings reported over the last few years regarding the role of TCF4 in brain development and function. Such findings are consistent with some cognitive and motor dysregulation found in children with PTHS, but further work is required to determine if the complete set of phenotypes in mouse models closely mimics the aberrant phenotypes in patients. Moreover, it is still unclear the extent to which the underlying pathophysiology is due to disruption in TCF4 function during brain development versus disruption in post-mitotic cells in the fully formed nervous system.

Considering that TCF4 seems to have specialized roles in different populations of NPCs, it is possible that its loss-of-function affects differentiation of discrete neuronal populations in certain regions of the brain, thus causing a wide variety of symptoms. Indeed, there are cell type–specific and region-specific differences in TCF4 expression1, suggesting that different subpopulations require different doses of TCF4 and are possibly differently vulnerable to TCF4 pathological alterations. The use of patient-derived cellular models in vitro might help unravel some of these aberrant phenotypes and provide a detailed understanding of the underlying pathophysiology related to TCF4.

In summary, TCF4 remains an elusive transcription factor. The precise molecular mechanisms through which TCF4 mutations contribute to PTHS pathophysiology, as well as the role of TCF4 variants in other psychiatric disorders such as SCZ, remain to be further elucidated. Additional exploration of the dynamic expression and function of the TCF4 gene throughout development together with the interplay between multiple TCF4 isoforms and different interacting partners is needed. TCF4 target genes are mostly unknown and evidence of in vivo TCF4 dimer function is currently lacking; therefore, further investigation on the role of TCF4-containing heterodimers in lineage commitment and differentiation is required, which could be undertaken through experiments that explore TCF4’s relationship with known neurogenic and oligogenic HLH transcription factors.

Although much is yet to be comprehended, the general role of TCF4 in psychiatric disease has clearly emerged, materializing TCF4 as a key regulator of neural function, including learning, memory, language, and sociability.

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Andrés Yunes for sharing resources. This study was financed through grants from the Pitt–Hopkins Research Foundation (PHRF) and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; grant #2020/11451-7), and through fellowships from FAPESP (#2018/03613-7) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES; Finance Code 001) to J.R.T.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alysson R. Muotri, Email: muotri@ucsd.edu

Fabio Papes, Email: papesf@unicamp.br.

References

- 1.Jung M, et al. Analysis of the expression pattern of the schizophrenia-risk and intellectual disability gene TCF4 in the developing and adult brain suggests a role in development and plasticity of cortical and hippocampal neurons. Mol. Autism. 2018;9:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13229-018-0200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brockschmidt A, et al. Severe mental retardation with breathing abnormalities (Pitt-Hopkins syndrome) is caused by haploinsufficiency of the neuronal bHLH transcription factor TCF4. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:1488–1494. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zweier C, et al. Haploinsufficiency of TCF4 causes syndromal mental retardation with intermittent hyperventilation (Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:994–1001. doi: 10.1086/515583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amiel J, et al. Mutations in TCF4, encoding a Class I basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, are responsible for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a severe epileptic encephalopathy associated with autonomic dysfunction. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:988–993. doi: 10.1086/515582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefansson H, et al. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:744–747. doi: 10.1038/nature08186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ripke S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smoller JW, et al. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del-Favero J, et al. European combined analysis of the CTG18.1 and the ERDA1 CAG/CTG repeats in bipolar disorder. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;10:276–280. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wray NR, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:668–681. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelernter J, et al. Genome-wide association study of post-traumatic stress disorder reexperiencing symptoms in >165,000 US veterans. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:1394–1401. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0447-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baratz KH, et al. E2-2 protein and Fuchs’s corneal dystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1016–1024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wieben ED, et al. A common trinucleotide repeat expansion within the transcription factor 4 (TCF4, E2-2) gene predicts Fuchs corneal dystrophy. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:5–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellinghaus D, et al. Genome-wide association analysis in primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis identifies risk loci at GPR35 and TCF4. Hepatology. 2013;58:1074–1083. doi: 10.1002/hep.25977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Berens NC, Ochandarena NE, Philpot BD. Region and cell type distribution of TCF4 in the postnatal mouse brain. Front. Neuroanat. 2020;14:42. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2020.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Pontual L, et al. Mutational, functional, and expression studies of the TCF4 gene in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:669–676. doi: 10.1002/humu.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henthorn P, Kiledjian M, Kadesch T. Two distinct transcription factors that bind the immunoglobulin enhancer microE5/kappa 2 motif. Science. 1990;247:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.2105528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corneliussen B, Thornell A, Hallberg B, Grundström T. Helix-loop-helix transcriptional activators bind to a sequence in glucocorticoid response elements of retrovirus enhancers. J. Virol. 1991;65:6084–6093. doi: 10.1128/JVI.65.11.6084-6093.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiaramello A, Soosaar A, Neuman T, Zuber MX. Differential expression and distinct DNA-binding specificity of ME1a and ME2 suggest a unique role during differentiation and neuronal plasticity. Mol. Brain Res. 1995;29:107–118. doi: 10.1016/0169-328X(94)00236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson P, Jögi A, Grynfeld A, Påhlman S, Axelson H. HASH-1 and E2-2 are expressed in human neuroblastoma cells and form a functional complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;274:22–31. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jögi A, Persson P, Grynfeld A, Påhlman S, Axelson H. Modulation of basic helix-loop-helix transcription complex formation by Id proteins during neuronal differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:9118–9126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moen MJ, et al. An interaction network of mental disorder proteins in neural stem cells. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1082. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sepp M, Kannike K, Eesmaa A, Urb M, Timmusk T. Functional diversity of human basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor TCF4 isoforms generated by alternative 5′ exon usage and splicing. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sepp M, Pruunsild P, Timmusk T. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome-associated mutations in TCF4 lead to variable impairment of the transcription factor function ranging from hypomorphic to dominant-negative effects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2873–2888. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forrest M, et al. Functional analysis of TCF4 missense mutations that cause Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:1676–1686. doi: 10.1002/humu.22160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murre C. Helix–loop–helix proteins and the advent of cellular diversity: 30 years of discovery. Genes Dev. 2019;33:6–25. doi: 10.1101/gad.320663.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du J, et al. RNA toxicity and missplicing in the common eye disease fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:5979–5990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.621607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mootha VV, et al. TCF4 triplet repeat expansion and nuclear RNA foci in Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015;56:2003–2011. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quednow BB, Brzózka MM, Rossner MJ. Transcription factor 4 (TCF4) and schizophrenia: Integrating the animal and the human perspective. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71:2815–2835. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1553-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quednow BB, et al. Schizophrenia risk polymorphisms in the TCF4 gene interact with smoking in the modulation of auditory sensory gating. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6271–6276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118051109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wirgenes KV, et al. TCF4 sequence variants and mRNA levels are associated with neurodevelopmental characteristics in psychotic disorders. Transl. Psychiatry. 2012;2:e112. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albanna A, et al. TCF4 gene polymorphism and cognitive performance in patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2014;152:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lennertz L, et al. Novel schizophrenia risk gene TCF4 influences verbal learning and memory functioning in schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2011;63:131–136. doi: 10.1159/000317844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu X, et al. Associations between TCF4 gene polymorphism and cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:683–689. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennand KJ, et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;473:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brzózka MM, Rossner MJ. Deficits in trace fear memory in a mouse model of the schizophrenia risk gene TCF4. Behav. Brain Res. 2013;237:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brzózka MM, Radyushkin K, Wichert SP, Ehrenreich H, Rossner MJ. Cognitive and sensorimotor gating impairments in transgenic mice overexpressing the schizophrenia susceptibility gene Tcf4 in the brain. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu X, et al. A survey of rare coding variants in candidate genes in schizophrenia by deep sequencing. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:858–859. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basmanav FB, et al. Investigation of the role of TCF4 rare sequence variants in schizophrenia. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2015;168:354–362. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sepp M, et al. The intellectual disability and schizophrenia associated transcription factor TCF4 is regulated by neuronal activity and protein kinase A. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:10516–10527. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1151-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodspeed K, et al. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: a review of current literature, clinical approach, and 23-patient case series. J. Child Neurol. 2018;33:233–244. doi: 10.1177/0883073817750490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zollino M, et al. Diagnosis and management in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: first international consensus statement. Clin. Genet. 2019;95:462–478. doi: 10.1111/cge.13506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenfeld JA, et al. Genotype-phenotype analysis of TCF4 mutations causing Pitt-Hopkins syndrome shows increased seizure activity with missense mutations. Genet. Med. 2009;11:797–805. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181bd38a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peippo M, Ignatius J. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Mol. Syndromol. 2012;2:171–180. doi: 10.1159/000335287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whalen S, et al. Novel comprehensive diagnostic strategy in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: clinical score and further delineation of the TCF4 mutational spectrum. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:64–72. doi: 10.1002/humu.21639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sweatt JD. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: intellectual disability due to loss of TCF4-regulated gene transcription. Exp. Mol. Med. 2013;45:e21. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marangi G, Zollino M. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome and differential diagnosis: a molecular and clinical challenge. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2015;4:168–176. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1564570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pitt D, Hopkins I. A syndrome of mental retardation, wide mouth and intermittent overbreathing. Aust. Paediatr. J. 1978;14:182–184. doi: 10.1111/jpc.1978.14.3.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Balkom IDC, Vuijk PJ, Franssens M, Hoek HW, Hennekam RCM. Development, cognition, and behaviour in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2012;54:925–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:429–440. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aronheim A, Shiran R, Rosen A, Walker MD. The E2A gene product contains two separable and functionally distinct transcription activation domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:8063–8067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quong MW, Massari ME, Zwart R, Murre C. A new transcriptional-activation motif restricted to a class of helix-loop-helix proteins is functionally conserved in both yeast and mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:792–800. doi: 10.1128/MCB.13.2.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massari ME, Jennings PA, Murre C. The AD1 transactivation domain of E2A contains a highly conserved helix which is required for its activity in both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:121–129. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bayly R, et al. E2A-PBX1 interacts directly with the KIX domain of CBP/p300 in the induction of proliferation in primary hematopoietic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:55362–55371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Denis CM, et al. Structural basis of CBP/p300 recruitment in leukemia induction by E2A-PBX1. Blood. 2012;120:3968–3977. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-411397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Denis CM, et al. Functional redundancy between the transcriptional activation domains of E2A is mediated by binding to the KIX domain of CBP/p300. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7370–7382. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Massari ME, et al. A conserved motif present in a class of helix-loop-helix proteins activates transcription by direct recruitment of the SAGA complex. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:63–73. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scheele JS, et al. The Spt-Ada-Gcn5-acetyltransferase complex interaction motif of E2a is essential for a subset of transcriptional and oncogenic properties of E2a-Pbx1. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2009;50:816–828. doi: 10.1080/10428190902836107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holmlund T, Lindberg MJ, Grander D, Wallberg AE. GCN5 acetylates and regulates the stability of the oncoprotein E2A-PBX1 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27:578–585. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang J, Kalkum M, Yamamura S, Chait BT, Roeder RG. E protein silencing by the leukemogenic AML1-ETO fusion protein. Science. 2004;305:1286–1289. doi: 10.1126/science.1097937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo C, Hu Q, Yan C, Zhang J. Multivalent binding of the ETO corepressor to E proteins facilitates dual repression controls targeting chromatin and the basal transcription machinery. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:2644–2657. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00073-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen W-Y, et al. A TAF4 coactivator function for E proteins that involves enhanced TFIID binding. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1596–1609. doi: 10.1101/gad.216192.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu N, et al. Different roles of E proteins in t(8;21) leukemia: E2-2 compromises the function of AETFC and negatively regulates leukemogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:890–899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809327116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Herbst A, Kolligs FT. A conserved domain in the transcription factor ITF-2B attenuates its activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;370:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Markus M, Du Z, Benezra R. Enhancer-specific modulation of E protein activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6469–6477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y, Ray SK, Yang XQ, Luntz-Leybman V, Chiu IM. A splice variant of E2-2 basic helix-loop-helix protein represses the brain-specific fibroblast growth factor 1 promoter through the binding to an imperfect E-box. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19269–19276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greb-Markiewicz B, Kazana W, Zarębski M, Ożyhar A. The subcellular localization of bHLH transcription factor TCF4 is mediated by multiple nuclear localization and nuclear export signals. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:15629. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52239-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muir T, Sadler-Riggleman I, Stevens JD, Skinner MK. Role of the basic helix-loop-helix protein ITF2 in the hormonal regulation of sertoli cell differentiation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2006;73:491–500. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bedeschi MF, et al. Impairment of different protein domains causes variable clinical presentation within Pitt-Hopkins syndrome and suggests intragenic molecular syndromology of TCF4. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2017;60:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kharbanda M, et al. Partial deletion of TCF4 in three generation family with non-syndromic intellectual disability, without features of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2016;59:310–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maduro V, et al. Complex translocation disrupting TCF4 and altering TCF4 isoform expression segregates as mild autosomal dominant intellectual disability. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2016;11:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0439-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steinbusch C, et al. Somatic mosaicism in a mother of two children with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2013;83:73–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zweier C, et al. Further delineation of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: phenotypic and genotypic description of 16 novel patients. J. Med. Genet. 2008;45:738–744. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.060129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tan A, Goodspeed K, Edgar VB. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: a unique case study. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2018;24:995–1002. doi: 10.1017/S1355617718000668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lingbeck JM, Trausch-Azar JS, Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL. E12 and E47 modulate cellular localization and proteasome-mediated degradation of MyoD and Id1. Oncogene. 2005;24:6376–6384. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.De Masi F, et al. Using a structural and logics systems approach to infer bHLH-DNA binding specificity determinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4553–4563. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khund-Sayeed S, et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in E-box motifs ACAT|GTG and ACAC|GTG increases DNA-binding of the B-HLH transcription factor TCF4. Integr. Biol. 2016;8:936–945. doi: 10.1039/C6IB00079G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang J, et al. Structural basis for preferential binding of human TCF4 to DNA containing 5-carboxylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:8375–8387. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shively CA, Liu J, Chen X, Loell K, Mitra RD. Homotypic cooperativity and collective binding are determinants of bHLH specificity and function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:16143–16152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818015116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Corneliussen B, et al. Calcium/calmodulin inhibition of basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factor domains. Nature. 1994;368:760–764. doi: 10.1038/368760a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Onions J, Hermann S, Grundström T. Basic helix-loop-helix protein sequences determining differential inhibition by calmodulin and S-100 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23930–23937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saarikettu J, Sveshnikova N, Grundström T. Calcium/calmodulin inhibition of transcriptional activity of E-proteins by prevention of their binding to DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41004–41011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhattacharya A, Baker NE. A network of broadly expressed HLH genes regulates tissue-specific cell fates. Cell. 2011;147:881–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang LH, Baker NE. E proteins and ID proteins: helix-loop-helix partners in development and disease. Dev. Cell. 2015;35:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Pooter RF, Kee BL. E proteins and the regulation of early lymphocyte development. Immunol. Rev. 2010;238:93–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawai-Kowase K, Kumar MS, Hoofnagle MH, Yoshida T, Owens GK. PIAS1 activates the expression of smooth muscle cell differentiation marker genes by interacting with serum response factor and Class I basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:8009–8023. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8009-8023.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fischer B, et al. E-proteins orchestrate the progression of neural stem cell differentiation in the postnatal forebrain. Neural Dev. 2014;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Furumura M, et al. Involvement of ITF2 in the transcriptional regulation of melanogenic genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:28147–28154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Beck GR, Zerler B, Moran E. Gene array analysis of osteoblast differentiation. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:61–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tanaka A, et al. Inhibition of endothelial cell activation by bHLH protein E2-2 and its impairment of angiogenesis. Blood. 2010;115:4138–4147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-223057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Parrinello S, et al. Id-1, ITF-2, and Id-2 comprise a network of helix-loop-helix proteins that regulate mammary epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:39213–39219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meinhardt G, Husslein P, Knöfler M. Tissue-specific and ubiquitous basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors in human placental trophoblasts. Placenta. 2005;26:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pagliuca A, Gallo P, De Luca P, Lania L. Class A helix-loop-helix proteins are positive regulators of several cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors’ promoter activity and negatively affect cell growth. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1376–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rothschild G, Zhao X, Iavarone A, Lasorella A. E proteins and Id2 converge on p57Kip2 to regulate cell cycle in neural cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:4351–4361. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01743-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lasorella A, Benezra R, Iavarone A. The ID proteins: master regulators of cancer stem cells and tumour aggressiveness. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:77–91. doi: 10.1038/nrc3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Javaux F, Donda A, Vassart G, Christophe D. Cloning and sequence analysis of TFE, a helix-loop-helix transcription factor able to recognize the thyroglobulin gene promoter in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1121–1127. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yoon SO, Chikaraishi DM. Isolation of two E-box binding factors that interact with the rat tyrosine hydroxylase enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:18453–18462. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)46921-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pscherer A, et al. The helix-loop-helix transcription factor SEF-2 regulates the activity of a novel initiator element in the promoter of the human somatostatin receptor II gene. EMBO J. 1996;15:6680–6690. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dörflinger U, et al. Activation of somatostatin receptor II expression by transcription factors MIBP1 and SEF-2 in the murine brain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:3736–3747. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.5.3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sanlioglu-Crisman S, Oberdick J. Functional cloning of candidate genes that regulate Purkinje cell- specific gene expression. Prog. Brain Res. 1997;114:3–20. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zweier C, et al. CNTNAP2 and NRXN1 are mutated in autosomal-recessive Pitt-Hopkins-like mental retardation and determine the level of a common synaptic protein in drosophila. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Forrest MP, Waite AJ, Martin-Rendon E, Blake DJ. Knockdown of human TCF4 affects multiple signaling pathways involved in cell survival, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and neuronal differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rannals MDD, et al. Psychiatric risk gene transcription factor 4 regulates intrinsic excitability of prefrontal neurons via repression of SCN10a and KCNQ1. Neuron. 2016;90:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chen ES, et al. Molecular convergence of neurodevelopmental disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;95:490–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schmidt-Edelkraut U, Daniel G, Hoffmann A, Spengler D. Zac1 regulates cell cycle arrest in neuronal progenitors via Tcf4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:1020–1030. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01195-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hill MJ, et al. Knockdown of the schizophrenia susceptibility gene TCF4 alters gene expression and proliferation of progenitor cells from the developing human neocortex. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2017;42:181–188. doi: 10.1503/jpn.160073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Forrest MP, et al. The psychiatric risk gene transcription factor 4 (TCF4) regulates neurodevelopmental pathways associated with schizophrenia, autism, and intellectual disability. Schizophr. Bull. 2018;44:1100–1110. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li M, et al. Integrative functional genomic analysis of human brain development and neuropsychiatric risks. Science. 2018;362:eaat7615. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang Y, et al. Transcription factor 4 safeguards hippocampal dentate gyrus development by regulating neural progenitor migration. Cereb. Cortex. 2020;30:3102–3115. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Imayoshi I, Kageyama R. bHLH factors in self-renewal, multipotency, and fate choice of neural progenitor cells. Neuron. 2014;82:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Quevedo M, et al. Mediator complex interaction partners organize the transcriptional network that defines neural stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2669. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10502-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hennig KM, et al. WNT/β-catenin pathway and epigenetic mechanisms regulate the Pitt-Hopkins syndrome and schizophrenia risk gene TCF4. Mol. Neuropsychiatry. 2017;3:53–71. doi: 10.1159/000475666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li H, et al. Disruption of TCF4 regulatory networks leads to abnormal cortical development and mental disabilities. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019;24:1235–1246. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0353-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen T, et al. Tcf4 controls neuronal migration of the cerebral cortex through regulation of Bmp7. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2016;9:94. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Page SC, et al. The schizophrenia-and autism-associated gene, transcription factor 4 regulates the columnar distribution of layer 2/3 prefrontal pyramidal neurons in an activity-dependent manner. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018;23:304–315. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Li G, Fang L, Fernández G, Pleasure SJ. The ventral hippocampus is the embryonic origin for adult neural stem cells in the dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2013;78:658–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mesman S, Bakker R, Smidt MP. Tcf4 is required for correct brain development during embryogenesis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2020;106:103502. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2020.103502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lindwall C, Fothergill T, Richards LJ. Commissure formation in the mammalian forebrain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007;17:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Flora A, Garcia JJ, Thaller C, Zoghbi HY. The E-protein Tcf4 interacts with Math1 to regulate differentiation of a specific subset of neuronal progenitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15382–15387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707456104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.D’Rozario M, et al. Type I bHLH proteins daughterless and Tcf4 restrict neurite branching and synapse formation by repressing neurexin in postmitotic neurons. Cell Rep. 2016;15:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Phan BN, et al. A myelin-related transcriptomic profile is shared by Pitt–Hopkins syndrome models and human autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Neurosci. 2020;23:375–385. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0578-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wedel M, et al. Transcription factor Tcf4 is the preferred heterodimerization partner for Olig2 in oligodendrocytes and required for differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:4839–4857. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Thaxton C, et al. Common pathophysiology in multiple mouse models of Pitt–Hopkins syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2018;38:918–936. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1305-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kennedy AJ, et al. Tcf4 regulates synaptic plasticity, DNA methylation, and memory function. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2666–2685. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]